Abstract

Background

Low levels of physical activity contribute to the generally poor physical health of older adults with schizophrenia. The associations linking schizophrenia symptoms, neurocognition, and physical activity are not known. Research is needed to identify the reasons for this population’s lack of adequate physical activity before appropriate interventions can be designed and tested.

Design and Methods

In this cross-sectional study, 30 adults aged > 55 years with schizophrenia were assessed on symptoms (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale), neurocognition (MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery) and physical activity (Sensewear ProArmband). Pearson’s bivariate correlations (two-tailed) and univariate linear regression models were used to test the following hypotheses: 1) More-severe schizophrenia symptoms are associated with lower levels of physical activity, and 2) More-severe neurocognitive deficits are associated with lower levels of physical activity.

Results

Higher scores on a speed-of-processing test were associated with more average daily steps (p = .002) and more average daily minutes of moderate physical activity (p = .009). Higher scores on a verbal working-memory task were associated with more average daily minutes of moderate physical activity (p = .05). More severe depressive symptoms were associated with more average daily minutes of sedentary activity (p = .03).

Conclusion

Physical-activity interventions for this population are imperative. In order for a physical-activity intervention to be successful, it must include components to enhance cognition and diminish psychiatric symptoms.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Physical Activity, Symptomatology, Neurocognition

Schizophrenia is a severe chronic psychotic disorder (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2007). Older adults with schizophrenia are an expanding segment of the population, and data indicate that their physical health status is exceedingly poor (Chafetz, White, Collins-Bride, Nickens, & Cooper, 2006; Kilbourne et al., 2005; Parks, Svendsen, Singer, & Foti, 2006). Low levels of physical activity contribute to this poor health status. Viertio et al. (2009) found, for example, that decrements in physical activity contribute to poor health outcomes, increased use of health services, and decreased quality of life in older adults with schizophrenia. In order to improve the physical activity levels of older adults with schizophrenia, tailored interventions are needed. Before interventions can be successfully designed and tested, however, researchers must identify the reasons for this population’s inadequate levels of physical activity.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2008) defines physical activity as any bodily movement that enhances health. Optimization of physical activity may help delay disability and maintain independence (Tirodkar, Song, Chang, Dunlop, & Chang, 2008). Physical activity also enhances mood and cognition (Deslandes et al., 2009). Limitations in physical activity may hinder a person’s ability to care for his or her health needs. The multitude of chronic medical conditions people with schizophrenia experience, such as chronic obstructive pulmondary disease, can jeopardize their ability to achieve optimal levels of physical activity.

Investigators have tested various physical-activity programs in people with schizophrenia that have included activities such as walking and weight training (Gorczynski & Faulkner, 2010). The impacts of these programs on physical activity levels were mixed. In general, the studies provide support for the physiological and psychological benefits of physical activity in people with schizophrenia; however, adherence to the programs was consistently low. To date, only one published study has described a physical-activity program that was focused on older adults with schizophrenia (Leutwyler, Hubbard, Vinogradov, & Dowling, 2012) and only one study has explored the barriers to physical activity in this population (Leutwyler, Jeste, Hubbard, & Vinogradov, 2013). These studies suggest that, though older adults with schizophrenia are interested in becoming more physically active, the symptoms of schizophrenia are often a considerable barrier to physical activity.

Schizophrenia symptoms can be categorized as positive, negative, depressive/anxious, disorganized, excitatory, and other (Poole, Tobias, & Vinogradov, 2000). Positive symptoms include hallucinations and delusions. Negative symptoms include apathy, emotional withdrawal, and motor retardation. Depressive/anxious symptoms include depression and anxiety. Disorganized symptoms include conceptual disorganization. Excitatory symptoms include tension and euphoric mood. Other symptoms include preoccupation, stereotyped thinking, and disorientation. These symptoms can significantly impact the physical health of people with schizophrenia. For example, investigators found a positive association between number of medical problems and severity of schizophrenia symptoms (Dixon, Postrado, Delahanty, Fischer, & Lehman, 1999; Friedman et al., 2002). Some patients with schizophrenia believe that engaging in effective self-care is not possible when psychotic symptoms become overwhelming (El-Mallakh, 2006). Inagaki et al. (2006) found that schizophrenia symptoms may play a role in the delay of diagnosis and treatment of cancer. For example, in patients with severe negative symptoms, by the time the cancer was diagnosed, the disease had advanced and was no longer amenable to first-line treatment; it was often not possible to provide early notification to patients who refused or interrupted treatment; and they had more difficulty understanding and cooperating with the treatment. In addition, symptomatology may limit insight into illness, which can lead to missed opportunities for participating in activities to prevent and screen for diseases (Copeland, Zeber, Rosenheck, & Miller, 2006; Jeste, Gladsjo, Lindamer, & Lacro, 1996). Less-than-adequate medical treatment has been associated with many factors in patients with schizophrenia, such as stigma and communication barriers (Leutwyler & Wallhagen, 2010). In the case of less-than-adequate medical treatment for comorbid medical conditions in these patients, investigators also found an association with higher depression scores and number of positive symptoms (Vahia et al., 2008).

Only one study has explored the relationship between psychiatric symptoms and aspects of physical activity (physical function) in older adults with schizophrenia (Viertio et al., 2009). In that study, a nationally representative sample of 6,927 persons in Finland self-reported mobility limitations and underwent performance tests. Self-reported mobility was assessed with questions about activities that involve mobility such as moving around the house, running, and bicycling. Performance tests in participants aged 55 and older included walking ability on a timed 6.1-m course, ability to rise from a chair, walking 2 m flat, walking 2 m on toes, climbing up and down two steps, squatting, and handgrip strength. Of the 6,927 persons evaluated, 185 participants were identified as having had a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder some time in their lives, as follows: schizophrenia (n = 61, mean age 53.4 years), other nonaffective psychosis (n = 79, mean age 57.9 years), and affective psychosis (n = 45, mean age 53.9 years). Interviews, case notes, and standard symptom scales were used to calculate summary scores for positive, disorganized, and negative symptoms in this subgroup. In the group with nonaffective psychosis, mobility difficulties were associated with greater severity of symptoms.

In addition to psychiatric symptoms, people with schizophrenia have impaired neurocognition (Keefe et al., 2006). Neurocognition links cognitive constructs, in theory, to particular brain regions, systems, and processes. Neurocognitive impairment is a central aspect of schizophrenia and is distinct from the symptomatology of the disease (Matza et al., 2006). Fundamental dimensions of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia include working memory, attention/vigilance, verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, reasoning and problem solving, speed of processing, and social cognition (Matza et al., 2006; Nuechterlein, 2004). Cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia is a strong predictor of impaired psychosocial functioning, affecting, for example, work and social behavior (Matza et al., 2006; McGurk, Mueser, DeRosa, & Wolfe, 2009). Neurocognition may also impact physical health.

Two studies have evaluated the relationship between neurocognition and physical function, but none have specifically explored physical activity and neurocognition in schizophrenia (Chwastiak et al., 2006; Friedman et al., 2002). In one study, investigators evaluated 124 institutionalized geriatric patients with schizophrenia to identify characteristics that best predicted changes in self-care functions associated with aging (Friedman et al.). Functional status, negative symptoms, cognitive functioning, and health status worsened over the course of the 4-year study. Path analysis demonstrated that concurrent changes in cognitive functioning had the largest effect on changes in functional status, with greater degrees of cognitive decline associated with increased loss in functional status. In Chwastiak and colleagues’ study (2006), researchers evaluated the interrelationship between neurocognitive function and physical function using baseline data from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) trial, a national multi-site trial of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy that collected data from more than 1,400 patients (ages 18–65 years, mean age 40.6 years). Neurocognitive function was measured using a neurocognitive assessment battery that included 11 measures of verbal fluency, working memory, verbal learning and memory, social cognition, motor function, attention and executive function. Results showed that more-severe neurocognitive impairment was associated with poorer physical function.

The studies by Chwastiak et al. (2006), Friedman et al. (2002), and Viertio et al. (2009) suggest that more-severe symptomatology and impaired neurocognition negatively impact physical function. The findings of these studies are limited, however, by the lack of objective assessment of physical activity and of a comprehensive neurocognitive assessment. In addition, no studies to date have evaluated the relationships between psychiatric symptoms and neurocognition and physical activity specifically in older adults with schizophrenia. The purpose of the present study was to explore these relationships in older adults with schizophrenia, testing the following hypotheses: 1) More-severe schizophrenia symptoms are associated with lower levels of physical activity, and 2) More-severe neurocognitive deficits are associated with lower levels of physical activity.

Methods

Theoretical Framework

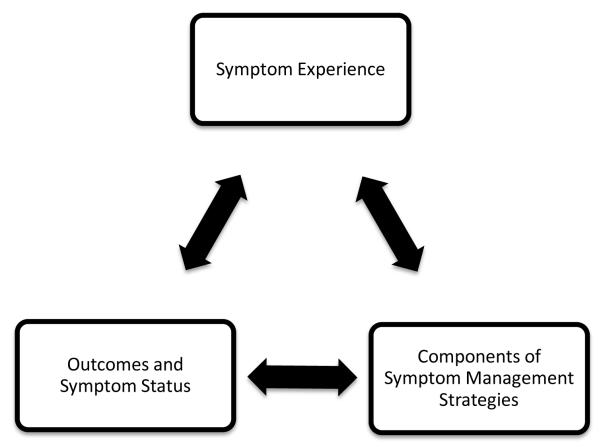

The theoretical framework for this study was the UCSF theory of symptom management (TSM; Dodd et al., 2001). The TSM embraces the perspective that effective management of a symptom or group of symptoms demands consideration of the symptom experience, symptom management strategy, and outcomes. The outcomes dimension specifies that outcomes emerge from the symptom management strategies as well as from the symptom experience. Symptom management is viewed as a dynamic process that is modifiable by both individual outcomes and the influences of the nursing domains of person, health/illness, and environment. Figure 1 depicts the conceptualized relationships among the dimensions of the theoretical framework.

Figure 1.

Relationships Among the Primary Dimensions of the Theory of Symptom Management. Adapted, with permission from John Wiley and Sons, from Dodd et al., 2001.

For the present study, our assessment of the symptom experience included evaluations of schizophrenia symptomatology and neurocognition. Individuals perceive these symptoms, evaluate the meaning of these symptoms, and respond to these meanings in a biopsychosocial manner. The outcome in the present study was physical activity. Our goal was to increase our understanding of the relationships between the symptom experience and outcome in order to be able to design physical-activity interventions tailored specifically for the older adult with schizophrenia.

Design

We used a cross-sectional design to examine our hypotheses. All participants gave written informed consent, and the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, and the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center approved the protocol. We maintained anonymity and confidentiality according to the committee’s guidelines.

Participants and Settings

We recruited participants from three sites: a transitional residential and day treatment center for older adults with severe mental illness; a locked residential facility for adults diagnosed with serious mental illnesses; and an intensive case-management program. We used multiple sites in order to obtain a sample with a range of psychiatric symptoms and levels of physical activity. IRB-approved information about the study was posted at these sites, and staff were also informed about the study. We also accepted participant referrals from the community and other participants. Participants were remunerated $60 after completion of the first assessment, $30 after they wore a physical-activity monitor for 1 week, and a bonus payment of $20 if they completed all of the study procedures.

Participants were English-speaking adults older, aged 55 years or older, with a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who passed a capacity-to-consent test based on comprehension of the consent form.

Procedures

Data collection began in May 2010 and concluded in July 2012. Assessments took place at a private meeting room at the facility the person attended or at the UCSF-SFVAMC Center for Neurobiology and Psychiatry or the Tenderloin Clinical Research Center. The assessment included completion of a demographic questionnaire, confirmation of diagnosis using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID), neurocognitive assessments, assessment of schizophrenia symptoms, and instruction on the wearing of a SenseWear Pro armband™ (SWA; BodyMedia Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) for 1 week. Additional clinical data obtained by research staff included blood pressure, waist circumference, weight, height, and patient report of smoking status and educational level. It took two to five meetings to complete the assessment, depending on the individual participants.

Measures

A trained member of the research staff administered all of the assessments. The research staff completed a formal practicum and lab training with the UCSF-SFVAMC Center for Neurobiology and Psychiatry. Research staff passed an observed practicum before administering the instruments to participants.

Symptomatology

Psychiatric symptoms were measured with the Extended Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987; Poole, Tobias, & Vinogradov, 2000). The extended PANSS is a 35-item instrument, with each item consisting of a 7-point (1-7) rating scale. The instrument comprises six subscales measuring positive, negative, excited, depressed-anxious, disorganized, and other symptoms. Lindenmayer et al. (2007) reported that the PANSS demonstrated good-to-excellent reliability in assessing symptoms and changes in symptoms during the course of treatment in clinical trials with participants diagnosed with schizophrenia. The scale takes approximately 60 min to administer. Items are summed to determine scores on the six subscales and the total score (the sum of all six subscales). Higher scores on the PANSS reflect more severe symptomatology.

Neurocognition

The Matrics Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) was used to assess neurocognition on each of the following seven domains identified as separable, fundamental dimensions of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia that have a likely sensitivity to intervention (Nuechterlein, 2004): Speed of processing (SOP), attention/vigilance, working memory, verbal learning, visual learning, reasoning and problem solving, and social cognition. Speed-of-processing tests include Trail Making Test: Part A, Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) Symbol Coding, and Category Fluency (animal naming). Attention/vigilance tests include Continuous Performance Test-Identical Pairs (CPT-IP). Working memory tests include the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS) Spatial Span and Letter-Number Span. Verbal learning includes the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised. Visual Learning includes the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test—Revised. Reasoning and problem solving includes Neuropsychology Assessment Battery (NAB) Mazes. Social cognition consists of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test: Managing Emotions. T-scores were calculated for each cognitive domain, selected individual tests, and an overall global composite score. Lower T-scores on the MCCB tests reflect poorer neurocognition.

Physical activity

Steps and energy expenditure were measured with the SenseWear Pro armband™ (SWA; BodyMedia Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). Patients wore the device over the left triceps muscle at all times, including while sleeping and except during bathing or water activities, for 5 days. This device samples data from a heat-flux sensor, a galvanic-skin-response sensor, a skin-temperature sensor, a near-body-temperature sensor, and a bi-axial accelerometer. Previous research determined that he SWA accurately estimates energy expenditure in older adults (Mackey et al., 2011). Outcome variables measured with this instrument included average daily steps taken and average daily minutes of physical activity categorized as sedentary (0–2.9 metabolic equivalents [METS]), moderate (3–5.9 METS), vigorous (6–8.9 METS), and very vigorous (> 9 METS). Participants were fitted with the SWA and informed about the activities the device would monitor during baseline data collection. Participants were reminded to take the SWA off only when showering or performing other activities during which the device might get wet. Additionally, they were given an information sheet that described proper placement and contact information for study staff if they had questions at any time. The devices were returned at the next scheduled meeting. If the participant was unable to attend, arrangements were made for a convenient time and location for retrieval.

Data Analysis

Physical-activity data were analyzed descriptively for the entire sample then compared across two groups for each of the two hypotheses: low-versus-high symptomatology and low-versus-high neurocognition. We used the median scores on the total PANSS and the global cognition score of the MCCB to determine the cut points for low versus high groups. Then, Pearson’s bivariate correlations (two-sided) were conducted on the entire sample. Variables that were significant at p < .10 in bivariate analysis were included in univariate linear regressions models. We estimated that, with a sample size of 30, at a significance level of .05, the null hypothesis that the Pearson correlation coefficient would equal zero would have 80% power to detect a population effect size of .531.

Results

A total of 30 participants were included in the analyses. Our sample was part of a larger study (N = 47) that evaluated the impact of neurocognition and schizophrenia symptoms on mobility. The 30 participants for the present study were those who had consented to the SWA-wearing period in addition to the mobility assessments. All 30 completed the study. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of participants were male, the average age was 60 years, and the average years of self-reported education were 14. More than half of the participants were current smokers. The mean body mass index (BMI) for the sample was 30.3 kg/m2 and mean waist circumference was 113 cm.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Physical Activity by Symptom Severity and Neurocognitive Function

| Symptom Severity | Cognitive Function | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Variable | Total Sample (N = 30) |

Low (n = 15) |

High (n = 15) |

Test Statistic (p-value) |

Low (n = 15) |

High (n = 15) |

Test Statistic (p-value) |

| Age (years) | 60 (4.0) | 59 (3.7) | 62 (4.0) | t = −2.0 (.07) | 60 (4.1) | 60 (4.1) | t = −0.4 (0.7) |

| Education (years) | 14 (4.0) | 12.3 (3.1) | 15.2 (4.2) | t = −2.1 (.04) | 13.7 (3.3) |

12.9 (2.5) |

t = 0.7 (0.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.3 (6.1) | 29.8 (7.1) | 30.7 (5.0) | t = −0.4 (0.7) | 28.3 (5.4) |

31.8 (6.3) |

t = −1.6 (0.1) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 112.9 (15.0) | 113.4 (16.7) |

112.4 (13.8) |

t = 0.2 (0.9) | 109.7 (12.1) |

115.3 (17.7) |

t = −1.0 (0.3) |

| No. daily steps taken | 4776 (3472.0) | 4936.2 (3810.1) |

4616.5 (3225.3) |

t = 0.2 (0.8) | 4265.7 (3430.7) |

5587.8 (3486.7) |

t = −1.0 (0.3) |

| Daily activity (min) | |||||||

| Sedentary (0–2.9 METS) | 1288 (147.0) | 1251.1 (166.6) |

1325.3 (118.8) |

t = −1.4 (0.2) | 1252.3 (177.8) |

1316.6 (101.7) |

t = −1.2 (0.2) |

| Moderate (3–5.9 METS) | 68 (65.0) | 69.2 (59.5) |

67.0 (71.6) |

t = 0.1 (0.9) | 56.3 (30.5) |

85.4 (86.7) |

t = −1.2 (0.2) |

| Vigorous (6–8.9 METS) | 1 (3.0) | 1.4 (4.1) | .27 (.7) | t = 1.1 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.5) | 1.5 (4.2) | t = −1.1(0.3) |

| Very vigorous (≥ 9 METS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Taking antipsychotic medication | 90% | 93% | 87% | X2 = 0.4 (0.5) | 87% | 93% | X2 = 0.3 (0.6) |

| Male | 60% | 67% | 53% | X2 = 0.6 (0.5) | 60% | 64% | X2 = 0.1 (0.8) |

| Smoker | X2 = 0.8 (0.7) | X2 = 2.3 (0.3) | |||||

| Current | 53% | 47% | 60% | 53% | 7% | ||

| Past | 27% | 33% | 20% | 20% | 36% | ||

| Never | 20% | 20% | 20% | 27% | 57% | ||

Note. Data presented are either mean (SD) or percent. BMI = body mass index; METS = metabolic equivalents.

The average Total PANSS score was 75 (SD = 27), indicating the sample was moderately ill (Leucht et al., 2005). The mean MCCB global overall composite T-score was 18.1 (SD = 14. 24, range = −14–42). Table 2 presents a summary of the performance on the MCCB domains (reported as T-scores) and the PANSS subscales. We calculated Global and Attention/Vigilance scores for only 29 of the 30 participants because 1 participant refused to complete the CPT-IP.

Table 2.

Mean (SD) Scores on the Extended Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale(PANNS) and T-Scores on the Matrics Consensus Cognitive Battery(MCCB) Subscales for Older Adults with Schizophrenia (N = 30).

| Scale and Subscales/Domains | Score |

|---|---|

| PANSS (psychiatric symptoms) | |

| PANSS Total | 75 (27.0) |

| PANSS Positive | 16 (8.8) |

| PANSS Negative | 13.5 (5.9) |

| PANSS Depressed/Anxious | 9.5 (3.7) |

| PANSS Disorganized | 8.3 (3.8) |

| PANSS Excited | 7.4 (2.8) |

| PANSS Other | 20.2 (8.4) |

| MCCB (neurocognition) | |

| Speed of processing | 22.4 (15.5) |

| Attention/vigilancea | 25.8 (14.0) |

| Working memory | 26.1 (13.3) |

| Verbal learning | 33.4 (10.1) |

| Visual learning | 34.4 (12.3) |

| Reasoning and problem solving | 38.9 (5.3) |

| Social cognition | 32.5 (9.0) |

| Category fluency | 40.2 (11.5) |

| Letter number span | 28.6 (13.4) |

| Global/overalla | 18.1 (14.2) |

n = 29.

All participants wore the armband for a minimum of 5 days. Table 1 lists the average daily steps taken and average number of minutes spent engaged in physical activity of each level of intensity.

The cut point on the PANSS for the low- versus high-symptomology groups was a score of 70. We found no significant differences between these two groups on any of the physical activity outcomes or demographic characteristics except for years of education, with the high-symptomatology group having significantly more years of education (Table 1). The high-symptomatology group did have worse average daily physical activity outcomes than the low symptomatology group, but the differences were not significant. Similarly, we found no significant differences between the low-(global cognition T-score < 19) versus high-neurocognition groups on physical activity outcomes or demographic characteristics (Table 1). The low-neurocognition group did have worse average daily physical activity scores than the high-neurocognition group on all measures except for sedentary activity, but the differences were not significant.

Pearson’s two-sided bivariate correlation analysis revealed positive associations between score on the speed of processing test (category fluency) and the average daily number of steps (p = .002) and average daily minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity (p = .009), scores on depressed/anxious symptoms and average daily minutes of sedentary activity (p = .03), and scores on the verbal working memory task (letter-number span) and average daily minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity (p = .05). Table 3 shows all variables that had significant correlations at p < .10 and were subsequently included in the univariate linear regression analyses.

Table 3.

Bivariate correlations between measures of physical activity and measures of symptom severity and neurocognitive function

| Covariate | Average Daily Steps Rho (p) |

Average Min of Sedentary Activity Rho (p) |

Average Min of Moderate Activity Rho (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PANSS (symptom severity) | |||

| Negative symptoms | −0.3 (.07) | 0.4 (.06) | −.2 (0.4) |

| Depressed/Anxious symptoms |

−.088 (.64) | 0.4 (.03)* | −.2 (0.2) |

| MCCB (neurocognitive function) |

|||

| Letter-number span (verbal working memory) |

0.4 (.06) | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.05)* |

| Speed of processing (fluency) |

0.5 (0.002)* | −0.2 (0.4) | 0.5 (0.009)* |

Note. MCCB = Matrics Consensus Cognitive Battery; PANNS = Extended Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

p < .05

Results of the univariate linear regression analyses are shown in Table 4. Correlations between the category fluency t-score and the average number of daily steps and average daily minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity, depressed/anxious symptom severity and average daily minutes in sedentary physical activity, and letter-number span t-score and average daily minutes in moderate-intensity physical activity remained significant in these analyses.

Table 4.

Mean Difference (Standard Error) in Response Variables (Physical Activity) per Standard Deviation (SD) of Predictor Variables (Symptom and Neurocognitive)

| Predictor Variables |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response Variables | Speed of Processing (Category Fluency) |

P- value |

Negative Symptoms |

P-value | Verbal Working Memory (LNS) |

P-value | Depressed/Anxious Symptoms |

P-value |

| Avg. daily no. steps | 162.1 (48.0) | .002* | −198.8 (104.7) | .07 | 90.7 (45.8) | .06 | - | - |

| Avg. daily min sedentary activity |

- | - | 8.7 (4.4) | .06 | - | - | 16.4 (6.9) | .03* |

| Avg. daily min moderate activity |

2.6 (0.9) | .009* | - | - | 1.8 (0.8) | .05* | - | - |

Note. Table reports results of univariate linear regression analyses. LNS = letter-number span.

p ≤ .05.

Discussion

Our findings in the present study provide support for our hypotheses that greater severity of schizophrenia symptoms and neurocognitive deficits are associated with lower levels of physical activity. In our sample of older adults with schizophrenia, better performance on a speed of processing task was associated with a greater number of average daily steps taken, better performance on speed of processing and verbal working memory tasks were associated with more time spent in moderate-intensity physical activity, and greater severity of depressed/anxious symptoms was associated with more time spent in sedentary activity. In addition, participants’ successful compliance with the SWA instructions demonstrates the feasibility of using this method for measuring physical activity levels in this population.

Previous studies (Chwastiak et al., 2006; Friedman et al., 2002; Viertio et al., 2009), have similarly found associations between physical activity levels and severity of symptoms and neurocognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. More recently, investigators have found an association between speed of processing and aspects of physical activity (e.g., gait speed) in older adults without serious mental illness (Donoghue et al., 2012; Rosano et al., 2012). Rosano et al. (2012) provide some rationale for this association by suggesting that walking requires perception and interpretation of the terrain’s properties and obstacles in surrounding space. In our sample, it is possible that slowed speed of processing may have impaired this interpretation process and limited the desire to walk.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. The small sample size made it difficult to control for potentially confounding factors, including BMI, use of antipsychotic medications, and smoking status. All of these factors could both contribute to level of physical activity and impact psychiatric symptoms. For example, a patient with a higher BMI may find it more physically difficult to engage in moderate-intensity activity than a similar patient with lower BMI. Higher BMI could also contribute to increased number and severity of depressive symptoms. In addition, specific psychiatric symptoms may have precluded some people from participating. For example, individuals lacking acknowledgment of diagnosis or insight into their disease may have declined to participate. Finally, because the treatment facilities from which we recruited the majority of participants are predominantly male, the majority of our sample was also male, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings to females.

Conclusion

Ours is the first study, to our knowledge, to explore the associations of neurocognitive deficits and schizophrenia symptoms with physical activity in older adults with schizophrenia. An understanding of these relationships is particularly important in order to design and implement effective physical activity interventions in this population.

Based on our findings as well as those of previous studies, an ideal physical activity program for this population would improve both speed of processing and physical activity levels. Maillot, Perrot, and Hartley (2012) found that exergame training improved physical function and speed of processing in a sample of older adults. The only published study exploring a physical activity program for older adults with schizophrenia suggests that exergames may be a feasible way to promote physical activity in this population (Leutwyler, Hubbard, Vinogradov, & Dowling, 2012). Future studies should explore the relationships between schizophrenia symptoms and neurocognitive function and physical activity longitudinally in a larger sample of patients from a variety of mental health settings in order to better understand the specific symptoms and cognitive domains that impact physical activity. In addition, patients’ self-report of physical activity would help increase our understanding of the types of physical activities older adults with schizophrenia perform on a daily basis and to determine which symptoms and cognitive domains influence these activities.

Nurses caring for this population can begin to improve the overall physical health of older adults with schizophrenia by encouraging patients and mental health facilities to incorporate physical activity into their daily routines. The use of active video games in patients’ homes or treatment facilities may be an ideal way to both promote physical activity and potentially improve speed of processing. Furthermore, administrators at both residential and outpatient facilities could provide opportunities for physical activity through establishment of routine physical activity groups. The groups could be simple walking groups facilitated by licensed or nonlicensed staff members or volunteers. As our and previous findings indicate, caregivers should also be aware that symptoms and cognitive difficulties may hinder a patient’s desire or ability to be more physically active and explore ways to address these barriers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the UCSF Academic Senate (Individual Investigator Grant), National Center for Research Resources (KL2R024130 to H.L. & UCSF-CTSI UL1 RR024131), and the National Institute of Nursing Research (P30-NR011934-0 to H.L.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health. The final, definitive version of the article is available at http://online.sagepub.com/.

Contributor Information

Heather Leutwyler, Assistant Professor, Department of Physiological Nursing University of California, San Francisco 2 Koret Way, N631A, Box 0610 San Francisco, California, 94143-0610.

Erin M. Hubbard, Department of Physiological Nursing University of California, San Francisco erin.hubbard@nursing.ucsf.edu.

Dilip V. Jeste, Estelle and Edgar Levi Chair in Aging Director, Sam and Rose Stein Institute for Research on Aging Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry & Neurosciences Director of Education, Clinical and Translational Research Institute University of California, San Diego President, American Psychiatric Association djeste@ucsd.edu.

Bruce Miller, A.W. Clausen Distinguished Professor of Neurology Director, Memory & Aging Center University of California, San Francisco bmiller@memory.ucsf.edu.

Sophia Vinogradov, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco and San Francisco VA Medical Center Sophia.Vinogradov@ucsf.edu.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.