Abstract

The anti-vascular function of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) inhibitor imatinib combined with paclitaxel has been demonstrated by invasive immunohistochemistry. The purpose of this study was 1. to noninvasively monitor the response to anti-PDGFR treatment and 2. to understand the underlying mechanism of this response. Thus, response to treatment was studied in a prostate cancer bone metastasis model using macromolecular (biotin-BSA-GdDTPA) dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI). PC-3MM2 bone metastases that caused osteolysis and grew in neighboring muscle showed high blood volume fraction (fBV) and vascular permeability (PS) at the tumor periphery, compared to muscle tissue and intraosseous tumor. Imatinib alone or with paclitaxel significantly reduced PS by 35% (one-tailed paired t-test p=0.045) and 40% (p=0.0003) respectively, whereas paclitaxel alone or no treatment had no effect. Based on changes in PS we hypothesized that imatinib interferes with the signaling pathway of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). This mechanism was verified by immunohistochemistry. It demonstrated reduced activation of both PDGFR-β and VEGFR2 in imatinib-treated mice. Our study therefore demonstrates that macromolecular DCE-MRI can be used to detect early vascular effects associated with response to therapy targeted to PDGFR and provides insight into the role played by VEGF in anti-PDGFR therapy.

Keywords: PDGFR, VEGFR, vascular permeability, macromolecular DCE-MRI

Introduction

Ligand-induced activation of the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor (PDGFR) stimulates the migration, proliferation, and survival of various cell types. PDGFR is thus involved in tumor progression, angiogenesis, and the regulation of interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) (1). The over-expression and activation (receptor auto-phosphorylation) of PDGF and PDGFR in a variety of tumors, makes PDGFR an attractive target for anti-cancer drug therapy (1,2). For this reason, many receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitors targeted against PDGFR have been developed and are being investigated in experimental models and in clinical trials, mostly for use in combination with conventional chemotherapy or radiotherapy. (2,3).

PDGFR is a particularly promising target because of its expression on both tumor cells and stromal cells (mostly cells associated with tumor vasculature: smooth muscle cells, pericytes, and endothelial cells) (1). Consequently, the blockade of PDGFR may improve the outcome of therapy even when the tumor cells do not express the receptor (4) or when the tumor cells are resistant to conventional therapy (5). For example, PDGFR inhibition can be effective in the setting of elevated tumor IFP, which acts as a barrier to drug uptake and interferes with tumor treatment (6). Indeed, in tumor models in which PDGFR expression is restricted to tumor stroma, an inhibitory PDGF aptamer and the PDGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571) reduced the IFP and increased the transcapillary transport and uptake of chemotherapeutic drugs (4). This indicates that the efficacy of chemotherapy can be enhanced through the inhibition of PDGF signaling.

PDGFR inhibitors can also act by sensitizing PDGFR-expressing endothelial cells to cytotoxic agents, thereby inducing an anti-vascular effect (7,8). This was demonstrated in a human prostate cancer bone metastasis model in which tumor-associated endothelial cells express phosphorylated PDGFR. Treatment of this model was initiated 3 days after implantation of tumor and lasted for 5 weeks. Treatment combining the cytotoxic drug paclitaxel and the PDGFR inhibitor imatinib, produced the most significant inhibition of tumor growth and best preservation of the bone structure compared to any of the drugs alone (8). This response was attributed to the combined effect of the two agents on tumor-associated endothelial cells, as evidenced by reduced phosphorylation of PDGFR on endothelial cells, fewer tumor-associated endothelial cells, and increased apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells and tumor cells (7,8). A similar model of prostate cancer bone metastasis in which cancer cells are multidrug-resistant showed comparable results. In this case, however, apoptosis was limited to the endothelial cells, indicating that the tumor vasculature was the primary target of imatinib in this model (5). Importantly, some of these preclinical studies were the basis for initiating a clinical study for this combined therapy in patients with androgen independent prostate cancer and metastases (3). In previous studies, the anti-vascular effect of the combined imatinib and paclitaxel treatment on bone metastases was detected by immunohistochemistry studies, which examined changes in proliferation, apoptosis, receptor phosphorylation, and microvessel density. Although immunohistochemistry is a direct method, it cannot inform on vascular functionality and cannot be used in vivo or repeatedly to monitor response to therapy in the same tumor. Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI), on the other hand, can provide surrogate measures of tumor vascular function in response to anti-angiogenic or anti-vascular therapy (9). Thus, the purpose of this study was to use DCE-MRI to examine changes in vascular function associated with response to anti-PDGFR therapy and to understand the underlying mechanism of this response.

Using the macromolecular contrast agent, biotin-BSA-GdDTPA, we demonstrate here that DCE-MRI can detect changes in blood volume and vascular permeability associated with tumor growth as well as with response to anti-PDGFR treatment. A short-term late-intervention treatment resulted in a significant decrease in vascular permeability even though the effect on tumor growth was not significant. This indicates that marcomolecular DCE-MRI has potential as an early indicator of the vascular effect of anti-PDGFR treatment. Furthermore, the significant decrease in vascular permeability in response to imatinib, in combination with paclitaxel or alone, suggested reduced VEGFR signaling that was confirmed by immunohistochemistry. Thus, in this case, macromolecular DCE-MRI also provided insight into the mechanism of response to therapy. In summary, this study highlights the value of macromolecular DCE-MRI in providing mechanistic insights and informing on drug molecular action in a noninvasive fashion.

Methods

Cell line and tumor model

PC-3MM2 (10) human prostate cancer cells were cultured as previously reported (5). Twenty-six male CD1 nude mice (Charles River Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, MA) were housed and maintained in facilities approved by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and animal care met all the current regulations and standards of the United States Department of Agriculture and the NIH Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare. The guidelines of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee were also followed.

The intratibial injection of tumor cells was performed essentially as previously reported (8). Briefly, CD1 nude mice (6–8 weeks of age) were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg; OVATION Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Deerfield, IL). An intratibial injection was carried out by drilling a 27-gauge needle through the inter-tubierositial dent and into the bone marrow space of the left tibia, after which 20 μl of the cell suspension (2 × 105 cells in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution) was deposited in the bone marrow.

Contrast materials

Biotin-BSA-GdDTPA (11,12) was derived from bovine serum albumin (BSA) by conjugation with biotin and GdDTPA (biotin-BSA-GdDTPA; approximately 80 kDa; relaxivity of 177 mM−1 s−1 per albumin and 7.55 mM−1 s−1 per Gd at 4.7T). An intravenous bolus dose of biotin-BSA-GdDTPA (4 μmol/kg (Gd: 92 μmol/kg) in 200 μl of PBS) was injected during dynamic (macromolecular) contrast-enhanced MRI to allow evaluation of vascular function, including blood volume and vascular permeability. The biotin label was used to visualize the distribution of the contrast material in histological sections.

BSA was also labeled with the rhodamine derivative ROX (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) (11), and this was used as a vascular marker for the histological analyses. BSA-ROX (1.4 μmol/kg) was administered intravenously in selected mice, 3–5 minutes before mice were euthanized.

In vivo MRI experiments

MR images were acquired on a 4.7T Biospec spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA) using micro-imaging gradients and a purpose-built knee coil. Before each imaging session, mice were anesthesized with isoflurane; a home-built catheter fitted with a heparin-flushed, 27-gauge needle was inserted into the tail vein; and the tumor-bearing limb was placed inside the knee coil. During imaging, body temperature was maintained using a heating pad and breathing was monitored.

The presence and location of the tumor were confirmed by axial, precontrast T2 weighted fast spin echo (fSE) images: TR 4500 ms; TE 15.6 ms; 4 averages; matrix 256 X 192; acquisition time 4 min 48 s; FOV 30 X 30 mm; slice thickness 1 mm. For DCE-MRI, three-dimensional, fast spoiled gradient recalled (3D-fSPGR) images were acquired before and sequentially for 45 minutes after intravenous bolus injection of the biotin-BSA-GdDTPA: precontrast flip angles 10º, 15º, 35º, 50º, and 70º; postcontrast flip angle 35º; TR 10 ms; TE 1.23 ms; 2 averages; matrix 128 X 128 X 32; acquisition time 81.92 s; frequency encoding direction head–foot, FOV 20 X 20 X 20 mm; slice thickness 624 μm; in-plane resolution 156 X 156 μm.

Analysis of dynamic MR data

The 3D datasets were zero-filled to 128 X 128 X 64. Maximal intensity projections (MIPs) were generated for each postcontrast time point, after subtraction of the precontrast dataset (Fig 1). 3D images were presented as MIP to highlight regions that showed pronounced contrast enhancement. Vessel density and regions of permeable vessels were extracted from the 3D datasets by pharmacokinetic pixel-by-pixel analysis of the accumulation of contrast material. Pixel-by-pixel analysis was done using MATLAB software (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA) to generate concentration maps of biotin-BSA-GdDTPA for selected slices of the 3D-fSPGR datasets (13,14). First, precontrast longitudinal relaxation rate (R1pre) maps were derived from the variable flip angle data by nonlinear best fit to Eq. (1):

| [1] |

where I is the signal intensity as a function of pulse flip angle α, TR is the repetition time (10 ms), and the preexponent term M0 includes the spin density and the T2 relaxation, which are assumed to be constant. Then, postcontrast R1 values (R1post) were calculated from precontrast and postcontrast 3D-fSPGR signal intensities (Ipre and Ipost respectively, acquired with a flip angle of 35º; Eq. (2)):

| [2] |

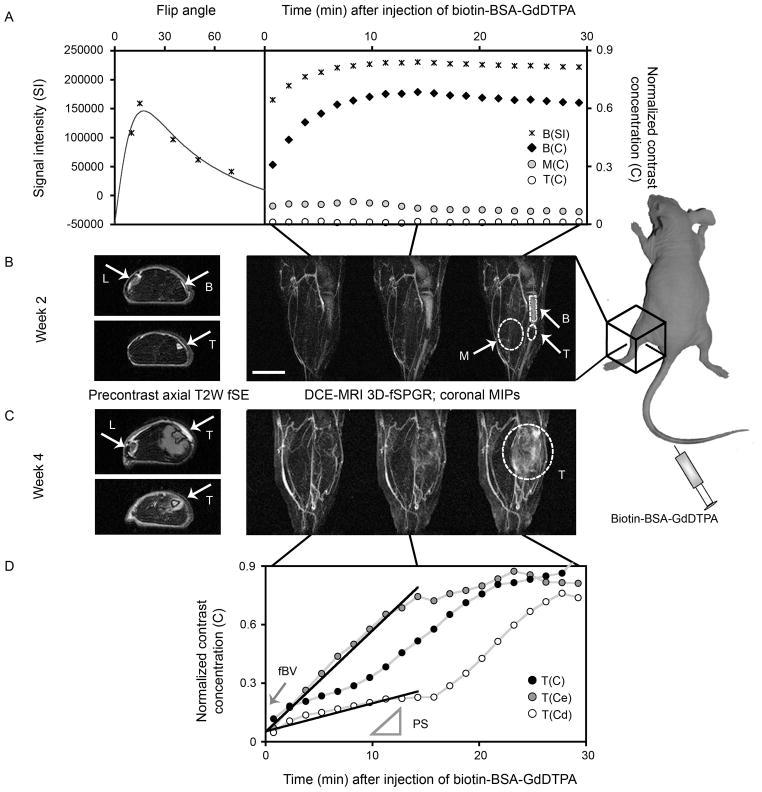

Figure 1.

DCE-MRI of prostate cancer bone metastasis model at early (week 2) and late (week 4) stages of tumor progression. A) Variations in signal intensity (B(SI); *) as a function of flip angle (left) and dynamic changes post contrast (right; flip angle 35°) were used to calculate normalized concentrations of the contrast material (biotin-BSA-GdDTPA; B(C); right) in selected regions of interest (ROIs): enhancing bone (B), muscle (M) and tumor (T). B, C) Precontrast axial T2W images (two selected slices each stage) are showing popliteal lymph node (L), normal bone (B), tumor-infiltrated bone (T; week 2) and tumor that exited to the muscle (T; week4). 3D-fSPGR images used for DCE-MRI are presented as coronal maximal intensity projections (MIPs) after subtraction of the precontrast 3D dataset. Selected post contrast time points (~1.5, 15 and 30 min) and ROIs (dashed-lines) are shown. Scale bar = 5 mm. D) Extratibial tumor contrast accumulation curve at week 4 (T(C)) represents combination of early enhancing pixels (T(Ce); containing permeable tumor blood vessels) and draining pixels (T(Cd); filled by interstitial convection). Linear regression of the first 15 min postcontrast (solid lines) was used for calculation of the tumor vascular parameters, blood volume fraction (fBV; intercept with time zero) and permeability surface area product (PS; the slope). Similar processing was used to generate fBV and PS maps (Fig 3).

Finally, concentration maps were calculated based on the relaxivity (R) of biotin-BSA-GdDTPA [177 mM−1 s−1; Eq. (3)]:

| [3] |

During the first 15 minutes post contrast the concentration of contrast material in the blood is stable (12) whereas contrast accumulation in the tumor is often linear and not yet noticeably affected by interstitial convection (14). Therefore, linear regression of the dynamic change in concentration during the first 15 minutes post contrast was used for the derivation of two vascular parameters, for selected ROIs and for each pixel in parametric maps (12,14) (Fig 1D):

The blood volume fraction (fBV): the ratio between the extrapolated concentration of biotin-BSA-GdDTPA in the ROI/pixel at the time of administration and the concentration of biotin-BSA-GdDTPA in the blood. The concentration in the blood was calculated for a region of interest in the femoral vein. This parameter indicates (micro)vascular density.

The permeability surface area product (PS; min−1): the initial rate of contrast accumulation (first 15 minutes) in the ROI/pixel normalized to initial blood concentration. PS reflects the leakage of macromolecules out of blood vessels and their accumulation in the tissues.

Numeric values for fBV and PS were calculated by selecting regions of interest that delineate the whole tumor and then averaging all pixels above threshold (in all relevant slices of the 3D stack of parametric maps). A PS value of three times the mean value of the muscle in the corresponding slice was used as threshold (Fig 2). This threshold was selected as optimal after performing multiple simulations using threshold values ranging between 1 and 5 times the mean value of muscle, and observing the remaining pixels in each slice to determine how efficiently low enhancing pixels (muscle) and late enhancing pixels (representing interstitial convection) were filtered while maintaining the early enhancing pixels (representing regions with highly permeable tumor vessels). Note that in this way some of the pixels in which the PS value was reduced towards background-muscle values due to treatment were neglected, possibly resulting in overestimation of PS after treatment and therefore causing the effects of treatment to appear less prominent; however, this method allows less bias than specifically selecting regions of high permeability.

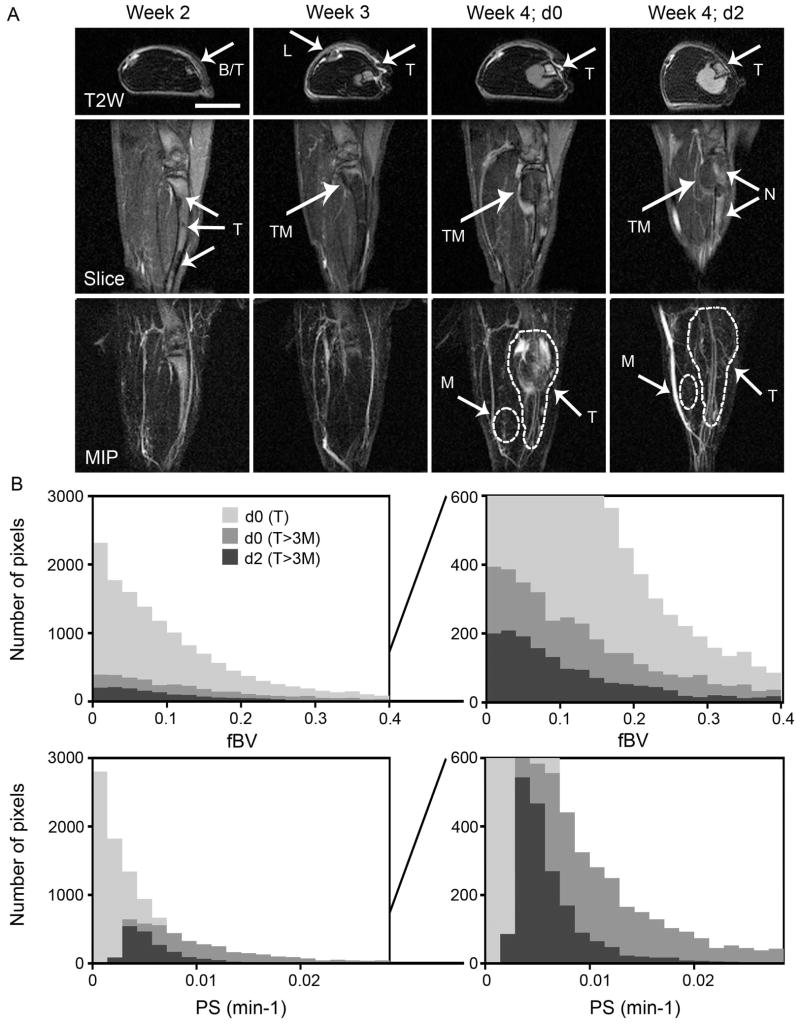

Figure 2.

DCE-MRI of late-intervention drug therapy. A) Precontrast axial T2W images (T2W), and selected slice (slice) and maximal intensity projection (MIP) of the 3D DCE-MRI at 30 min postcontrast showing popliteal lymph node (L), bone partially infiltrated with tumor (B/T), tumor (T), tumor that exited to the bone (TM) and necrotic regions (N) for a representative mouse. Combined treatment with imatinib and paclitaxel started one week after the tumor started to exit the bone (d0) and imaging was repeated two days later (d2). Scale bar = 5 mm. B) Histograms of blood volume fraction (fBV) and permeability (PS). fBV and PS were calculated for each pixel in the 3D datasets. PS histograms represent pixels in tumor ROI (dashed line in A); all pixels (d0(T)) and pixels above threshold (three times the mean value in the muscle in each slice; d0(T>3M) and d2(T>3M)). This method enables semiautomatic calculation of vascular parameters at the tumor periphery and eliminates the bias due to the need of carefully drawing ROI around tumor periphery in each slice. fBV histograms represent fBV values in the same pixels chosen for calculation of PS. Averaging values for pixels above threshold was used to quantify the response to drug therapy (Fig 5).

For the presentation of parametric maps (Fig 3), the stacks of fBV and PS maps (generated for sequential slices of interest) were projected to show the mean value of each pixel in the axial plane. No threshold was used. The mean value ± SD is reported for each experimental group. Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the changes due to treatment and differences between groups.

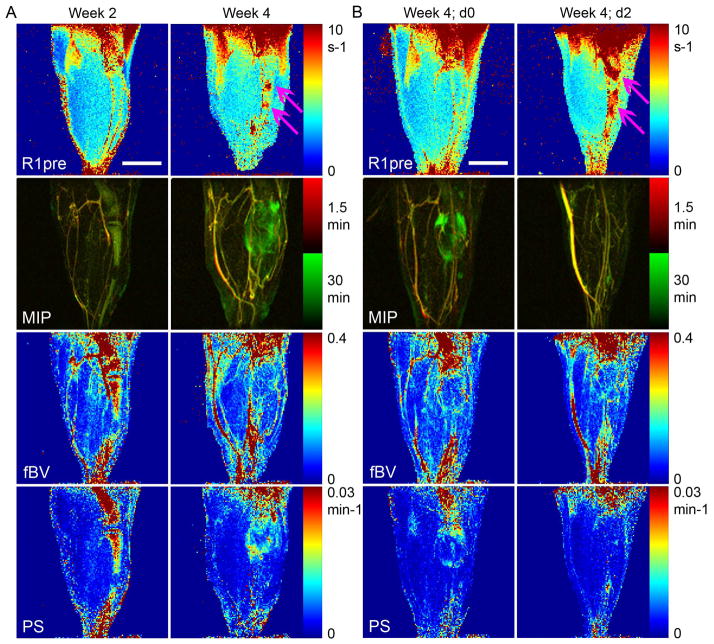

Figure 3.

Parametric changes during tumor progression and in response to late-intervention drug therapy. Precontrast R1 maps (R1pre; necrotic regions are indicated by pink arrows), MIPs overlay, blood volume fraction (fBV) maps and permeability surface area product (PS) maps (fBV and PS were generated using similar processing as in Fig 1). Overlay of MIPs from the first time point (1.5 min; red) post contrast and later time point (30 min; green) is used to better show the initial and constant contrast enhancement (co-localization of red and green, resulting in yellow, representing big blood vessels) and dynamic contrast enhancement (green only). A) Representative mice (same mice as in Fig 1), 2 and 4 weeks after the intratibial injection of tumor cells. B) Representative mouse (same mouse as in Fig 2), before treatment (d0) and at the end of two days (d2) combined treatment with imatinib and paclitaxel. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Drugs and interventional treatments

The animals were assigned to one of the following treatment groups: imatinib plus paclitaxel for 2 days (n=9); imatinib only for 2 days (n=3); paclitaxel only for 2 days (n=4) followed by imatinib for 2 more days (n=2 out of 4); control (untreated; n=5).

Imatinib, which was kindly provided by Novartis Pharma (Basel, Switzerland), was dissolved in distilled water to a concentration of 10 mg/mL. Animals were treated daily by an intraperitoneal injection (50 mg/kg). Paclitaxel (Bristol Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ) was diluted in distilled water to a concentration of 2 mg/mL, and was delivered once by intraperitoneal injection (8 mg/kg) on the first day of treatment. Mice were imaged weekly to evaluate tumor growth starting 2 weeks after the inoculation of tumor cells. The late-intervention drug treatment was started 1 week after the tumor was first observed to exit the bone and proliferate into the muscle (typically 4–5 weeks after tumor inoculation).

Mice were imaged again 2 days later (1–2 hours after the administration of the third dose of the imatinib, if treatment included this drug). The group treated by paclitaxel followed by imatinib was also imaged at day 4 of paclitaxel treatment (day 2 of imatinib treatment).

Staining of contrast-enhanced tissue specimens

Tissue was collected from an additional group of mice (n=6; untreated) approximately 1 week after the tumor exited the bone. To preserve biotin (biotin-BSA-GdDTPA) and fluorescent tag (BSA-ROX), specimens were fixed in Carnoy’s solution (6:3:1 ethanol/chloroform/acetic acid) for 48 h at room temperature. Tissue samples were then washed with PBS for 30 min, decalcified with 10% EDTA (pH 7.4) for 7–10 days at 4°C, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4–6 μm) were deparaffinized with a xylene substitute (Safeclear II; Fisher Scientific Company LLC, Kalmazoo, MI) for 5 min; rehydrated with 100%, 95%, and 70% ethanol and double-distilled water for 5 min each time; and equilibrated in PBS for 5 min. After nonspecific binding was blocked using 2% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, sections were incubated in blocking solution containing avidin-FITC (1:40; Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at room temperature to allow visualization of the biotinylated contrast material. Following nuclear staining (Hoechst; 1:1000 in PBS; Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) for 5 min at room temperature, sections were mounted (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and viewed under a confocal microscope (FluoView™ FV1000; Olympus America INC. Melville, NY). The fluorescent-labeled vascular marker BSA-ROX, injected just before tissue retrieval, remained visible following the above processing.

Immunohistochemistry of expression and activation of PDGF and VEGF receptors

Tissue samples were fixed in PLP (2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer containing 0.075 M lysine and 0.01 M sodium periodate) for 24 h; washed with PBS for 30 min; decalcified as described above; placed in PBS containing 10%, 15%, and 20% sucrose for 4–16 h each at 4°C; embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA); and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections (8–9 μm) were allowed to dry in air for 30 min, postfixed in acetone for 20 min at −20°C, dried again in air for 30 min, and then equilibrated in PBS for 5 min. Following blocking of nonspecific binding using PBS with 4% fish gel (Cold Water Fish Skin Gelatin, 40%, Aurion; Electron Microscopy Science) for 20 min at room temperature, sections were incubated with rat monoclonal antibodies directed against mouse CD31 (PECAM-1; 1:200 in blocking solution; BD Bioscience Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, sections were washed in PBS three times for 5 min each and further incubated for 1 h with secondary antibodies (Texas Red-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG; 1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) at room temperature. After washing in PBS three times for 5 min each, sections were briefly blocked again for 5 min and then sequential sections were incubated with one of the following: rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against mouse/human phosphorylated (Tyr1214) VEGFR2 (1:50 in blocking solution; Spring Bioscience, Fremont, CA) for 1 h at room temperature, or rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against PDGFR-β or phosphorylated (Tyr1021) PDGFR-β (1:50 in blocking solution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, sections were washed in PBS three times for 5 min each and further incubated for 1 h with secondary antibodies (FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG; 1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc) at room temperature. After being washed in PBS three times for 5 min each, sections were counterstained (Hoechst), mounted, and viewed as described above.

Results

Tumor progression in bone marrow and adjacent muscles subsequent to osteolysis were distinctly observed by macromolecular DCE-MRI-derived vascular mapping

We first detected the tumor lesion as a hyper-intense region in the precontrast T2-weighted image as soon as 2 weeks post inoculation of tumor cells in the tibia (Fig 1A, B, 2A). In DCE-MRI using the macromolecular contrast material biotin-BSA-GdDTPA the highly-vascularized normal bone marrow showed high initial contrast enhancement, reflecting high blood volume fraction (fBV, 0.481±016; n=6), and rapid contrast accumulation as a result of high vascular permeability (PS, 0.0185±0.004; n=6) relative to muscle tissue (fBV, 0.094±0.031; PS, 0.0022±0.002; n=6). However, contrast enhancement and vascular parameters were dramatically reduced when tumor cells grew to replace the bone marrow (fBV, 0.038±0.024; PS, 0.0009±0.001; n=6).

During subsequent weeks, tumors that started out as single or several reduced-intensity foci on DCE-MRI extended throughout the bone marrow, induced osteolysis, and eventually exited the bone into the neighboring muscle (typically at 3–4 weeks after tumor inoculation). A week later, tumor growing outside the bone showed markedly elevated vascular function (Fig 1, 2). The initial contrast enhancement of the extratibial tumor (fBV; 0.123±0.054; n=6) was slightly higher than that of the muscle and of tumor growing in the bone but lower than that of normal bone marrow. The rate of contrast accumulation in the extratibial tumor (PS, 0.0249±0.019; n=6) was similar to that of normal bone marrow but showed more linear kinetics in the first 15 min (Fig 1D; T(C)) rather than the saturation kinetics shown by normal bone marrow (Fig 1A; B(C)). At the late stages of tumor progression (one week after tumors start exiting the bone) contrast accumulation curves were sensitive to the region of interest selected (Fig 1C, D; week4). Total enhancing region at 30 min postcontrast (T(C)) showed continuous accumulation. In contrast, when data was followed over time for individual pixels, a dual phased accumulation was observed. Some pixels showed early rapid accumulation of contrast during the first 10–20 min postcontrast and then reached a steady-state. Based on previous work (12,14), these early enhancing pixels (T(Ce)) contain leaky tumor and peri-tumor blood vessels. Other pixels maintained baseline levels of contrast agent and started to show contrast accumulation later. These are draining pixels (T(Cd)), into which the macromolecular contrast material is drained by interstitial convection from the early enhancing pixels. Therefore, linear regression of the first 15 min post contrast was used for more sensitive calculation of the tumor vascular parameters (fBV and PS; Fig 1) on a pixel-by-pixel basis and generation of vascular parametric maps (Fig 3).

Microscopic validation of biodistribution of macromolecular contrast material: altered DCE-MRI contrast enhancement is due to replacement of bone marrow by growing tumor followed by fibrosis/necrosis

To detect the microscopic biodistribution of the contrast material, biotin-BSA-GdDTPA was made visible by staining with avidin-FITC (12). BSA-ROX injected within 5 min before euthanasia and tumor retrieval, served as a vascular marker (Fig 4).

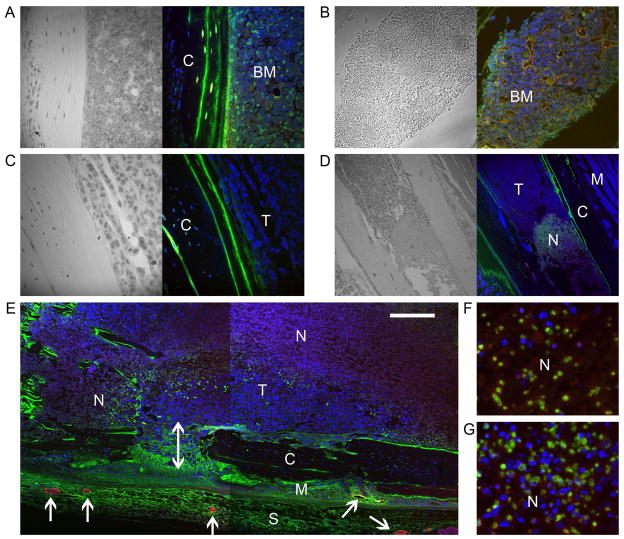

Figure 4.

Microscopic distribution of macromolecular contrast material. Tissues were retrieved 45–60 min after the injection of biotin-BSA-GdDTPA (all) and immediately after the injection of BSA-ROX (a vascular marker; red; A–E only). Tissue sections were further stained for biotin using avidin-FITC (green; A–E) or stained with vascular markers (green, F, G). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). Transmitted light images (enhanced with hematoxylin) are also shown besides selected sections (A–D). A, B) Bone marrow (BM) in normal (contra lateral) tibia. C) Tumor-infiltrated (T) tibia. D) Necrotic region (N) in tumor-infiltrated tibia. E) Composite image showing necrotic (N) and viable tumor (T) regions inside the bone, viable tumor growing across (double headed arrow) the compact bone (C) into the neighboring muscle (M), and enlarged blood vessels in the skin (S) and muscle tissue at the tumor periphery (arrows). Large blood vessels (B, E) are doubly stained by both intravenously-injected markers (showing in yellow or orange-red depending on the relative concentration of markers). Note that red blood cells are still trapped in some of the vessels together with the contrast material. F, G) Necrotic regions nonspecifically stained with p-PDGFR-β (F) and p-VEGFR2 (G), possibly indicating autofluorescence. See Fig 6 to compare with specific stain. Scale bar = 100 μm (A–C); 400 μm (D); 240 μm (E); 50 μm (F, G).

Normal tibia, contralateral to the tibia inoculated with tumor, showed high staining for biotin-BSA-GdDTPA, both in the bone marrow and in the bone matrix, and showed accumulation in cells populating the bone marrow such as fibroblasts, megakaryocytes and monocytes (Fig 4A). Large perfused blood vessels stained with BSA-ROX were also detected in the normal tibia marrow (Fig 4B). In contrast, tumor infiltrated tibia did not show any uptake of biotin-BSA-GdDTPA or perfused blood vessels (Fig 4C) consistent with vascular collapse in the tumor region. Indeed, at the time of tissue retrieval (4–5 weeks after inoculation of the tumor cells), fibrotic/necrotic regions were observed inside the tibia (Fig 4D, E), probably resulting from reduced blood supply. These regions had a higher intrinsic R1 relaxation rate than did the normal or tumor-infiltrated bone marrow, such that we could also detect these necrotic regions in the precontrast R1 maps (Fig 3; R1pre). It should be noted that necrotic regions stained for biotin (Fig 4D), but contrast enhancement and accumulation were not apparent in the MRI-derived vascular function maps. A possible explanation is the differences in sampling time (15 min postcontrast for vascular mapping versus 45–60 min for tissue retrieval for histology). Alternatively the stain may reflect auto-fluorescence as these regions were also nonspecifically enhanced when tissue slices were stained for various receptors (Fig 4F, G).

Even at the advanced stage of tumor progression when some necrosis is observed, other tumor regions inside the tibia remained viable (Fig 4D, E; viable tumor (T)) and some of the viable tumor cells were able to cause bone osteolysis and exit the bone (Fig 4E; double headed arrow). Whereas tumor growing in the bone did not stain for biotin-BSA-GdDTPA, tumor that exited the bone and grew in the surrounding muscle demonstrated very high staining, indicating the presence of leaky blood vessels (Fig 4E; skin (s) and tumor-infiltrated muscle (M)), in accordance with the high vascular permeability and contrast accumulation detected by MRI (Fig 1–3). In addition, large perfused blood vessels stained with BSA-ROX were detected at the tumor periphery (Fig 4E; arrows), in regions highly stained for biotin-BSA-GdDTPA.

High vascular permeability characteristic of tumor lesions growing in the muscle, after exiting the bone, was significantly reduced by anti-PDGFR therapy

We detected high vascular permeability as massive extravasation and rapid accumulation of the macromolecular contrast material in DCE-MRI, and as high intensity staining in tissue sections (Fig 1–4). Vascular permeability was especially pronounced one week after the tumor exited the bone at the tumor rim/periphery. At this point we initiated late intervention drug treatment, starting immediately at the end of the imaging session of that day (d0). Animals were imaged again 2 days later (d2; if treatment included imatinib, imaging was performed after administration of the third dose of drug).

In the group that received imatinib plus paclitaxel we detected a dramatic decrease in contrast accumulation and vascular permeability (PS) at the periphery of the extratibial tumor on d2 of combined therapy (Fig 2A, 3B). In some of the mice we also detected high signal intensity and high precontrast R1 (Fig 3B), reflecting necrosis, but this was probably not exclusively a result of therapy, since we detect necrosis also in untreated mice (Fig 3A). We used a threshold (see methods) to quantify changes in vascular parameters in response to treatment, showing a reduction in both intensity and number of pixels with high PS values (Fig 2B) and overall a significant reduction in PS due to combined therapy (Fig 5; two-tailed paired t-test p=0.0006; n=9). Blood volume fraction (fBV) showed either decrease (Fig 2B) or increase (not shown), and on the average a slight and not statistically significant increase (Fig 5A).

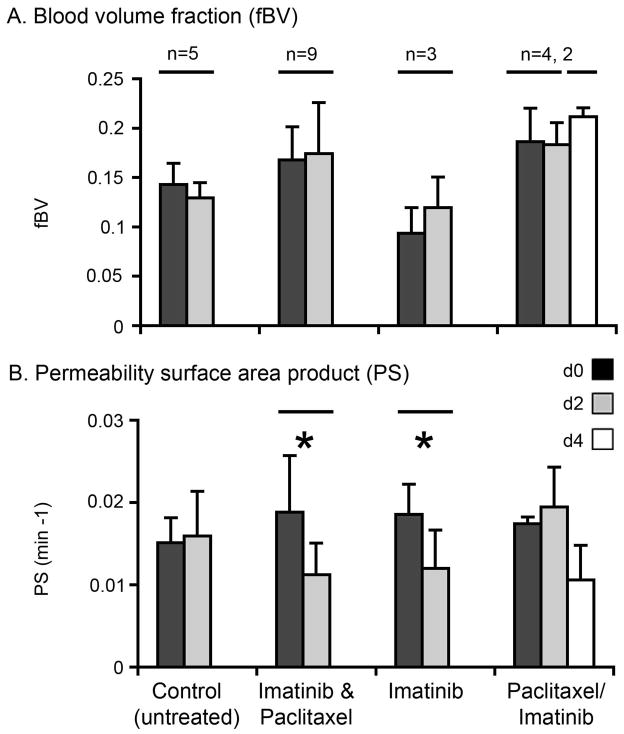

Figure 5.

Quantified vascular parameters in response to late-intervention drug therapy. fBV (A) and PS (B) were quantified from DCE-MRI performed before treatment (d0) and at the end of 2 (d2) or 4 (d4) days of control (untreated) or treatment as indicated (average ± SD). Average values for pixels above threshold as shown in Fig 2 were used to quantify the response to drug therapy. * Indicates one-tailed paired t-test, p < 0.05. (n) Indicates number of mice per group.

In untreated (control) mice, there were no significant overall changes between d0 and d2 (Fig 5; n=5). Treatment with imatinib alone resulted in a decrease in PS (two-tailed paired t-test p=0.09; one-tailed paired t-test p=0.045; n=3) and had no significant effect on fBV, similar to the results for the combination treatment with paclitaxel. However, paclitaxel alone had no significant effect on either parameter (n=4), though the subsequent addition of imatinib for 2 more days again resulted in a drop in permeability (n=2; Fig 5B). No significant change in tumor size was detected over the 2 days of therapy in any of the experimental groups.

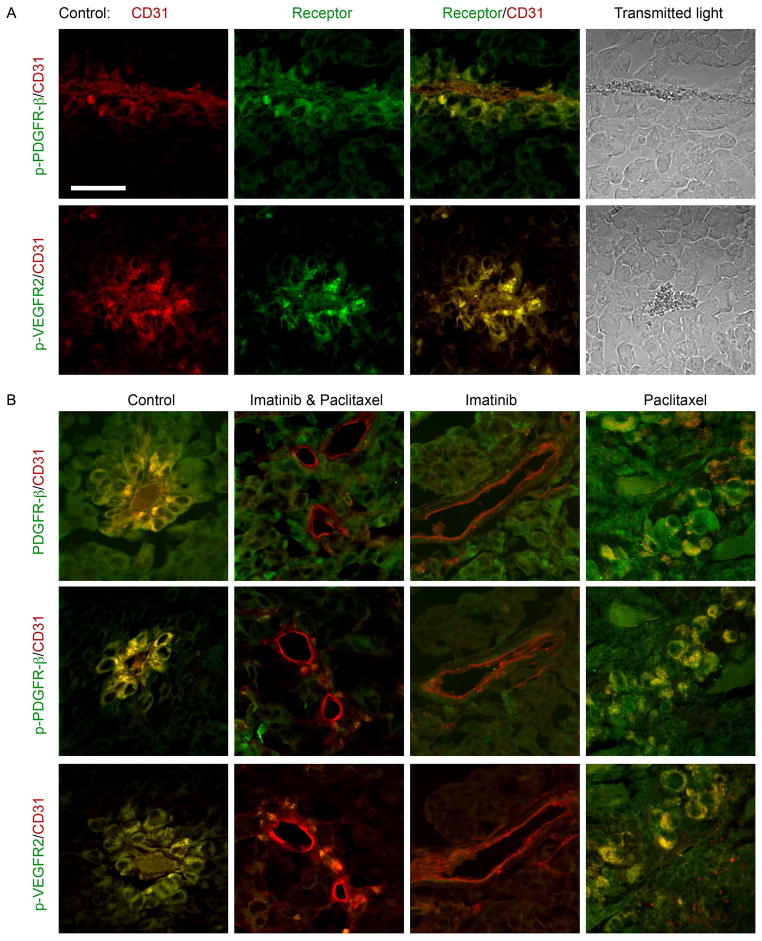

Reduced vascular permeability produced by anti-PDGFR therapy was associated with reduced activation of VEGFR2

PDGF is not a direct vascular permeability factor. However, the high permeability of the tumor growing in the muscle and its significant reduction by anti-PDGFR therapy suggested that another growth factor, VEGF, also known as vascular permeability factor, is involved as well. To study the role of VEGF in this tumor model, we immunostained tissue sections for VEGFR2 (the receptor responsible for the vascular permeability effect of VEGF (15)), as well as for PDGFR-β (Fig 6). Control (untreated) tumor showed high expression and activation (phosphorylation) of PDGFR-β around blood vessels in cells that stained positively for the endothelial marker CD31. These CD31-positive cells also expressed activated VEGFR2. These PDGFR-β– and VEGFR2–activated vessels were found in the tumor portion that exited the bone and grew in the muscle. In addition, the vessel walls looked irregular and were lined with loosely connected rounded cells (Fig 6A, B). In contrast, staining for these receptors was low in blood vessels in tumors treated with imatinib, alone or in combination with paclitaxel, but not in tumors treated with paclitaxel alone (Fig 6B). Thus, these histological results indicate that the mechanism of the response to anti-PDGFR treatment involves the VEGF signaling pathway, as suggested by the DCE-MRI findings.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry data investigating the molecular mechanism of late-intervention drug therapy. Tumor sections were doubly stained for the endothelial marker CD31 (red) and one of the following receptors (green): PDGFR-β, activated (phosphorylated) PDGFR-β (p-PDGFR-β) or activated VEGFR2 (p-VEGFR2). A) Control (untreated) tumor, one week after tumor exited the bone. CD31 and receptor staining are presented alone and as an overlay. Also included are transmitted light images in which the red blood cells can be seen inside the vessels. B) Control and 2-day treated tumors, stained for various markers. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Discussion and Conclusions

Tumor vasculature is becoming a popular target for development of new drugs. As a result, there is an increasing need for accurate and reliable methods to evaluate the response to these vasculature-targeting drugs. We have shown here that macromolecular DCE-MRI can be used (1) to detect changes in vascular function during the progression of prostate cancer in a bone metastasis model and (2) to monitor early response to anti-vascular therapy targeted to the PDGF receptor. Further, our findings indicate that the mechanism of response to PDGFR inhibition involves VEGF.

The clinically approved, low-molecular-weight (<1000 Da) Gd chelates often used in DCE-MRI for the diagnosis and detection of response to therapy can facilitate the clinical decision-making process (16,17). Macromolecular contrast materials (MMCM; >30,000 Da) as well as small Gd chelates with a high binding affinity to serum albumin that can achieve a pseudo-macromolecular performance are also being developed. Some of these agents have already been approved for clinical use in the European Union (18,19).

Due to their higher molecular size and weight, MMCM act as blood pool agents with prolonged retention in the circulation, and selectively extravasate only out of neovasculature (typical to tumors). These properties improve the detection of the vascular phase by DCE-MRI, thus allowing the efficient quantification of tumor vasculature. This enables the more accurate measurement of physiologically relevant parameters such as vascular permeability (PS) and blood volume (fBV), rather than the Ktrans measured by conventional DCE-MRI, which reflects a mixture of permeability and flow (20,21).

In this DCE-MRI study we used the MMCM biotin-BSA-GdDTPA. The DCE-MRI results combined with histological data indicate that the vascularity of the tumor differs depending on its microenvironment and suggests that tumor growing in the confined compartment of the bone is compressing and eliminating existing blood vessels, whereas, after osteolysis, tumor growing in the muscle induces angiogenesis, resulting in the proliferation of leaky blood vessels. Precontrast R1 mapping was also valuable in predicting fibrosis/necrosis that developed from low enhancing tumor regions inside the bone and that was later confirmed by histology.

The results may also reflect the effect of IFP on trans capillary transport. Indeed, IFP is elevated in many solid tumors resulting in reduced transcapillary transport, whereas IFP is much lower at the tumor periphery, allowing leakage of macromolecules out of permeable tumor vessels (6,22). We observed the same behavior here. Vascular permeability was low in the tumor core and in tumor-infiltrated tibia (where IFP is expected to be especially elevated due to tumor growth in the confines of bone) and high at the tumor periphery. In normal bone marrow and muscle IFP should be low and accumulation of macromolecular contrast agent would be dictated by the characteristic vascular permeability of the tissue and uptake into cells. It is important to bear in mind, however, that the kinetic model we used here to analyze the data assumes a fast water exchange across the vessel wall. Thus, slow or intermediate exchange will result in underestimation of vascular volume, although the measurement of vascular permeability will not be affected.

Noninvasive monitoring of tumor vascular function enabled us to detect early response to treatment. Whereas previous data in a similar tumor model showed that combined treatment was the most effective in inhibiting tumor growth and secondary metastasis due to anti-vascular effects (8), our results indicate that the initial reduction in permeability in response to intervention therapy is mostly due to imatinib. Our findings are consistent with two small scale clinical studies reported in glioma and chordoma patients which observed reduced enhancement in low molecular weight DCE-MRI following treatment with imatinib alone or in combination with hydroxyurea (23,24). The anti-vascular effect of several other RTK inhibitors of PDGFR was also observed by low molecular weight DCE-MRI (25–28). However, the anti-vascular effect in these cases is not surprising, since most of these RTK inhibitors are not specific to PDGFR, and also block VEGFR. Imatinib, on the other hand, is a significantly more potent inhibitor of PDGFR (IC50=100nM) than a blocker of VEGFR (IC50 for R1=25,000 nM and IC50 for R2=11,000 nM) (29). Therefore, our results suggest that imatinib might interfere with VEGFR activity through a mechanism other than direct blockade of the receptor.

The high vascular permeability at the tumor-muscle interface and its significant reduction by imatinib are remarkably similar to the observations we made previously in subcutaneous VEGF–over-expressing C6 tumors (C6-pTET-VEGF) following VEGF withdrawal (12). Indeed, in the present study, immunohistochemistry staining verified that both PDGFR-β and VEGFR2 were highly activated in the blood vessels of untreated tumors, but were barely detectable after 2 days of imatinib treatment. Our experiments therefore showed that macromolecular DCE-MRI may be useful not only in detecting response to treatment but also in providing insight into the mechanism of the response.

Our results further suggest that VEGF expression in this tumor model is regulated by PDGF. PDGF may cause angiogenesis directly by inducing the proliferation and migration of endothelial and smooth muscle cells. It can also elicit angiogenesis indirectly by inducing the expression of VEGF in a PI3K-mediated fashion (30). Through this mechanism, PDGF may stimulate angiogenesis in early stages of tumor progression (30) and at the tumor front, before hypoxia takes over as the major regulator of VEGF expression (31). Imatinib-mediated down-regulation of VEGF was also associated with reduced IFP and improved oxygenation, such that oxygen levels may still be involved in changes in VEGF expression resulting from interference in the PDGF signaling pathway (32).

Our findings were made only in a late-stage PC-3MM2 bone metastasis model in response to 2 days of treatment with imatinib-paclitaxel. However, initial results indicate that prolonging the combined treatment period to 1 week may maintain low permeability or induce further decrease in vascular permeability (data not shown). More studies are required to determine the effect of long-term late-intervention treatment on vascular permeability and tumor growth in this tumor model. Additional studies are also required to compare biotin-BSA-GdDTPA to the clinically approved low-molecular-weight GdDTPA with respect to the reliability of characterization of vascular parameters and differences in spatial and temporal patterns of contrast enhancement.

Tumors differ in terms of the pattern and intensity of expression of various cytokines, growth factors, and their receptors and the interaction between the tumor cells and the microenvironment. For these reasons, tumors will respond differently to various inhibitors and cytotoxic drugs, and these differences should be determined at an early stage of treatment to allow for treatment adjustment. In this context, this study demonstrates that macromolecular DCE-MRI can serve as a powerful tool both for diagnosis and for treatment monitoring purposes. Finally, as we demonstrated here, macromolecular DCE-MRI also provides insights into the mechanism of the response to treatment.

Acknowledgments

Hagit Dafni is an Odyssey Fellow, supported by the Odyssey Program and the Houston Endowment, Inc., Scientific Achievement Fund at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

This study was funded in part by Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Programs (to S.M.R., PC060032) and in part by NIH NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (to shared resources at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, P30-CA016672).

References

- 1.Pietras K, Sjoblom T, Rubin K, Heldin CH, Ostman A. PDGF receptors as cancer drug targets. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(5):439–443. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Board R, Jayson GC. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR): a target for anticancer therapeutics. Drug Resist Updat. 2005;8(1–2):75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathew P, Thall PF, Jones D, Perez C, Bucana C, Troncoso P, Kim SJ, Fidler IJ, Logothetis C. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor inhibitor imatinib mesylate and docetaxel: a modular phase I trial in androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3323–3329. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietras K, Rubin K, Sjoblom T, Buchdunger E, Sjoquist M, Heldin CH, Ostman A. Inhibition of PDGF receptor signaling in tumor stroma enhances antitumor effect of chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2002;62(19):5476–5484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SJ, Uehara H, Yazici S, Busby JE, Nakamura T, He J, Maya M, Logothetis C, Mathew P, Wang X, Do KA, Fan D, Fidler IJ. Targeting platelet-derived growth factor receptor on endothelial cells of multidrug-resistant prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(11):783–793. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heldin CH, Rubin K, Pietras K, Ostman A. High interstitial fluid pressure - an obstacle in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(10):806–813. doi: 10.1038/nrc1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uehara H, Kim SJ, Karashima T, Shepherd DL, Fan D, Tsan R, Killion JJ, Logothetis C, Mathew P, Fidler IJ. Effects of blocking platelet-derived growth factor-receptor signaling in a mouse model of experimental prostate cancer bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(6):458–470. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.6.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SJ, Uehara H, Yazici S, Langley RR, He J, Tsan R, Fan D, Killion JJ, Fidler IJ. Simultaneous blockade of platelet-derived growth factor-receptor and epidermal growth factor-receptor signaling and systemic administration of paclitaxel as therapy for human prostate cancer metastasis in bone of nude mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64(12):4201–4208. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gossmann A, Helbich TH, Kuriyama N, Ostrowitzki S, Roberts TP, Shames DM, van Bruggen N, Wendland MF, Israel MA, Brasch RC. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as a surrogate marker of tumor response to anti-angiogenic therapy in a xenograft model of glioblastoma multiforme. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;15(3):233–240. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pettaway CA, Pathak S, Greene G, Ramirez E, Wilson MR, Killion JJ, Fidler IJ. Selection of highly metastatic variants of different human prostatic carcinomas using orthotopic implantation in nude mice. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2(9):1627–1636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dafni H, Gilead A, Nevo N, Eilam R, Harmelin A, Neeman M. Modulation of the pharmacokinetics of macromolecular contrast material by avidin chase: MRI, optical, and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry tracking of triply labeled albumin. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(5):904–914. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dafni H, Israely T, Bhujwalla ZM, Benjamin LE, Neeman M. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor 165 drives peritumor interstitial convection and induces lymphatic drain: magnetic resonance imaging, confocal microscopy, and histological tracking of triple-labeled albumin. Cancer Res. 2002;62(22):6731–6739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziv K, Nevo N, Dafni H, Israely T, Granot D, Brenner O, Neeman M. Longitudinal MRI tracking of the angiogenic response to hind limb ischemic injury in the mouse. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(2):304–311. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dafni H, Cohen B, Ziv K, Israely T, Goldshmidt O, Nevo N, Harmelin A, Vlodavsky I, Neeman M. The role of heparanase in lymph node metastatic dissemination: dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of Eb lymphoma in mice. Neoplasia. 2005;7(3):224–233. doi: 10.1593/neo.04433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gille H, Kowalski J, Li B, LeCouter J, Moffat B, Zioncheck TF, Pelletier N, Ferrara N. Analysis of biological effects and signaling properties of Flt-1 (VEGFR-1) and KDR (VEGFR-2). A reassessment using novel receptor-specific vascular endothelial growth factor mutants. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(5):3222–3230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noworolski SM, Henry RG, Vigneron DB, Kurhanewicz J. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in normal and abnormal prostate tissues as defined by biopsy, MRI, and 3D MRSI. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(2):249–255. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu G, Rugo HS, Wilding G, McShane TM, Evelhoch JL, Ng C, Jackson E, Kelcz F, Yeh BM, Lee FT, Jr, Charnsangavej C, Park JW, Ashton EA, Steinfeldt HM, Pithavala YK, Reich SD, Herbst RS. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as a pharmacodynamic measure of response after acute dosing of AG-013736, an oral angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors: results from a phase I study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5464–5473. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goyen M, Shamsi K, Schoenberg SO. Vasovist-enhanced MR angiography. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(Suppl 2):B9–14. doi: 10.1007/s10406-006-0162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daldrup-Link HE, Brasch RC. Macromolecular contrast agents for MR mammography: current status. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(2):354–365. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1719-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choyke PL. Contrast agents for imaging tumor angiogenesis: is bigger better? Radiology. 2005;235(1):1–2. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2351041773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leach MO, Brindle KM, Evelhoch JL, Griffiths JR, Horsman MR, Jackson A, Jayson GC, Judson IR, Knopp MV, Maxwell RJ, McIntyre D, Padhani AR, Price P, Rathbone R, Rustin GJ, Tofts PS, Tozer GM, Vennart W, Waterton JC, Williams SR, Workman P. The assessment of antiangiogenic and antivascular therapies in early-stage clinical trials using magnetic resonance imaging: issues and recommendations. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(9):1599–1610. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain RK. Delivery of molecular and cellular medicine to solid tumors. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46(1–3):149–168. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casali PG, Messina A, Stacchiotti S, Tamborini E, Crippa F, Gronchi A, Orlandi R, Ripamonti C, Spreafico C, Bertieri R, Bertulli R, Colecchia M, Fumagalli E, Greco A, Grosso F, Olmi P, Pierotti MA, Pilotti S. Imatinib mesylate in chordoma. Cancer. 2004;101(9):2086–2097. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desjardins A, Quinn JA, Vredenburgh JJ, Sathornsumetee S, Friedman AH, Herndon JE, McLendon RE, Provenzale JM, Rich JN, Sampson JH, Gururangan S, Dowell JM, Salvado A, Friedman HS, Reardon DA. Phase II study of imatinib mesylate and hydroxyurea for recurrent grade III malignant gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2007;83(1):53–60. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marzola P, Degrassi A, Calderan L, Farace P, Nicolato E, Crescimanno C, Sandri M, Giusti A, Pesenti E, Terron A, Sbarbati A, Osculati F. Early antiangiogenic activity of SU11248 evaluated in vivo by dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in an experimental model of colon carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(16):5827–5832. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muruganandham M, Lupu M, Dyke JP, Matei C, Linn M, Packman K, Kolinsky K, Higgins B, Koutcher JA. Preclinical evaluation of tumor microvascular response to a novel antiangiogenic/antitumor agent RO0281501 by dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI at 1.5 T. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(8):1950–1957. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura K, Taguchi E, Miura T, Yamamoto A, Takahashi K, Bichat F, Guilbaud N, Hasegawa K, Kubo K, Fujiwara Y, Suzuki R, Shibuya M, Isae T. KRN951, a highly potent inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, has antitumor activities and affects functional vascular properties. Cancer Res. 2006;66(18):9134–9142. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batchelor TT, Sorensen AG, di Tomaso E, Zhang WT, Duda DG, Cohen KS, Kozak KR, Cahill DP, Chen PJ, Zhu M, Ancukiewicz M, Mrugala MM, Plotkin S, Drappatz J, Louis DN, Ivy P, Scadden DT, Benner T, Loeffler JS, Wen PY, Jain RK. AZD2171, a pan-VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, normalizes tumor vasculature and alleviates edema in glioblastoma patients. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(1):83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchdunger E, Cioffi CL, Law N, Stover D, Ohno-Jones S, Druker BJ, Lydon NB. Abl protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 inhibits in vitro signal transduction mediated by c-kit and platelet-derived growth factor receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295(1):139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang D, Huang HJ, Kazlauskas A, Cavenee WK. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in endothelial cells by platelet-derived growth factor through the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Cancer Res. 1999;59(7):1464–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Detmar M, Brown LF, Berse B, Jackman RW, Elicker BM, Dvorak HF, Claffey KP. Hypoxia regulates the expression of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor (VPF/VEGF) and its receptors in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108(3):263–268. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12286453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vlahovic G, Rabbani ZN, Herndon JE, 2nd, Dewhirst MW, Vujaskovic Z. Treatment with Imatinib in NSCLC is associated with decrease of phosphorylated PDGFR-beta and VEGF expression, decrease in interstitial fluid pressure and improvement of oxygenation. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(8):1013–1019. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]