Abstract

Background

Abnormal acid gastroesophageal reflux is common in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and is considered a risk factor for its development. Retrospective studies have suggested improved outcomes in patients treated with anti-acid therapy. The aim of this study was to determine the association between anti-acid therapy and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Methods

Patients with IPF were identified from the placebo arms of the three IPFnet randomized clinical trials. Case report forms were designed to prospectively capture data regarding gastroesophageal reflux diagnosis and treatment. These data were analyzed to determine the relationship between use of anti-acid therapy (i.e. proton pump inhibitors and histamine-2 blockers) and change in forced vital capacity using a longitudinal repeated-measures model. Secondary outcomes analyzed included acute exacerbation, all-cause hospitalization, and all-cause mortality.

Findings

Two hundred and forty-two patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis were randomized to receive placebo therapy. Fifty-one percent were taking anti-acid therapy upon enrollment. There were no significant differences in demographics and pulmonary physiology between patients taking and not taking anti-acid therapy. After adjustment for sex, baseline forced vital capacity %predicted, and baseline diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide %predicted, patients taking anti-acid therapy at baseline had a slower decline in forced vital capacity (estimated change over 30-weeks of -0.06 liters vs. -0.12 liters, p-value = 0.05). Patients taking anti-acid therapy at baseline had fewer acute exacerbations (no events versus nine events, p-value <0.01) during the study period.

Interpretation

The use of anti-acid therapy was associated with a slower decline in forced vital capacity over time and fewer acute exacerbations in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. These findings support the hypothesis that abnormal acid gastroesophageal reflux contributes to disease progression and suggest that anti-acid therapy may be beneficial in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive, fibrotic lung disease of unknown cause with a median survival of 2-3 years following diagnosis.(1, 2) Several therapies have been studied for the treatment of IPF, including three trials sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-supported Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network (IPFnet): Sildenafil Trial of Exercise Performance in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (STEP-IPF),(3) Anticoagulant Effectiveness in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (ACE-IPF),(4) and Prednisone, Azathioprine, and N-Acetylcysteine: A Study that Evaluates Response in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (PANTHER-IPF).(5) However, no therapy has been proven to impact clinically meaningful outcomes and recently published evidence-based guidelines for the management of IPF recommended against the routine use of all known pharmacologic agents.(2, 4-8)

A high prevalence of abnormal acid gastroesophageal reflux (GER) has been observed in patients with IPF (9-11) and is considered a risk factor for its development.(1) There are data to suggest that medical and surgical treatment of GER in patients with IPF may be beneficial, presumably through reducing the acidity and/or frequency of microaspiration.(2, 12) Small case series have shown long-term stabilization in forced vital capacity (FVC) and oxygenation in patients with documented GER who were treated with medical and/or surgical therapy.(13, 14) Additional data have shown the presence of pepsin in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with acute exacerbation of IPF, suggesting a role for GER and microaspiration in this important clinical event.(15) Most recently, a two-center retrospective cohort study found that patient-reported use of anti-acid therapy at the time of diagnosis (predominantly proton-pump inhibitors) was associated with significantly longer survival time.(16) Thus, there is increasing evidence to support a role for GER and microaspiration in the pathogenesis and progression of IPF.(12)

The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between the routine use of anti-acid therapy (PPI and/or histamine-2 blockers [H2B]) and IPF disease progression using prospectively-collected data from the placebo arms of the three IPFnet randomized clinical trials. The primary measure of disease progression was change in FVC over time. Other secondary outcomes included time-to-acute-exacerbation, all-cause hospitalization, and all-cause mortality. Our hypothesis was that use of anti-acid therapy (i.e. PPI/H2B) would be associated with slower disease progression and fewer clinically meaningful events.

METHODS

Study Patients

Study patients were identified from the placebo arms of three IPFnet randomized controlled trials: STEP-IPF,(3) ACE-IPF,(4) and PANTHER-IPF.(5) All patients had well-defined IPF (Figure S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Briefly, STEP-IPF investigated the impact of sildenafil treatment on change in six-minute walk test over 12 weeks in patients with advanced IPF.(3) Advanced IPF was defined as carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) of less than 35% of the predicted value. ACE-IPF investigated the impact of warfarin treatment on progression-free survival over 48 weeks in patients with progressive IPF.(4) Progressive IPF was defined as a history of worsening dyspnea or physiologic deterioration. This study was stopped early due to a lack of benefit and evidence of increased mortality in patients randomized to warfarin. PANTHER-IPF investigated the impact of triple therapy with prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine (NAC), NAC monotherapy, or placebo on change in FVC over 60 weeks in IPF patients with mild-to-moderate functional impairment.(5) Mild-to-moderate impairment was defined by an FVC of ≥ 50% predicted and a DLCO of ≥ 30% predicted. This study is ongoing to determine the safety and efficacy of monotherapy with NAC, but partial data from the placebo group are available due to premature stopping of the triple-therapy arm for futility and possible harm. This study was exempt from IRB approval due to the use of existing de-identified data.

Prospective Collection of Data

Across the IPFnet trials, detailed clinical and GER-related variables were prospectively collected at baseline and each follow-up visit using standard case report forms (CRFs). These forms were specifically designed to capture information regarding the diagnosis of abnormal GER and the treatments used for GER (Figure S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). These data elements included information on GER-related co-morbidities (hiatal hernia and Barrett’s esophagus), method of GER diagnosis (symptoms, barium swallow test, 24-hour pH monitoring, and endoscopy), as well as GER-specific treatment (lifestyle modifications, anti-acid therapy [PPI/H2B], and surgical therapy with fundoplication).

Definition of the Treatment Groups

Patients were identified as “taking PPI/H2B” if they reported either of these medications at the baseline visit prior to randomization. Patients were identified as “not taking PPI/H2B” if they did not report use of either of these medications at the baseline visit. Furthermore, data on self-reported PPI and H2B use were recorded during each follow-up visit.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was the estimated change in FVC at 30 weeks (the mean follow-up time). All IPFnet trials had a standardized protocol for the measurement of FVC at specified intervals. Key secondary outcomes included acute exacerbation, all-cause hospitalization, all-cause mortality, and a composite endpoint including all three of these variables. Acute exacerbations were determined centrally by the IPFnet Adjudication Committee as part of the parent clinical trials using pre-specified criteria (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix).(17) The committee was blinded to the treatment status of the patients. Additional outcomes included six-minute walk distance (6MWD), dyspnea score (as measured by the University of California, San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire), and quality of life (as measured by the St. George Respiratory Questionnaire).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline data by treatment groups was reported as mean (standard deviation), median (25th, 75th) for continuous variables and as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. Statistical comparisons between those taking and not taking PPI/H2B were performed using the Wilcoxon test or Chi-square tests as appropriate. The primary analysis compared the mean response profile of the FVC (in liters) between treatment groups with terms for time, PPI/H2B treatment, and time by PPI/H2B treatment while adjusting for sex, baseline FVC %predicted, and baseline DLCO %predicted using a longitudinal repeated-measures model. The treatment effect was assumed to be linear over time and was reported as the estimated 30-week change with a corresponding 95% confidence interval. All measurements of FVC including baseline were treated as response variables. A compound-symmetry covariance matrix was assumed and confidence intervals and p-values were based on empirical standard errors. Secondary outcomes including 6MWD, dyspnea score, and the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire total score were modeled in a similar fashion. Unadjusted survival estimates were obtained using Kaplan-Meier curves for the following outcomes: acute exacerbations, all-cause hospitalizations, all-cause mortality, and a combined endpoint of acute exacerbation, all-cause hospitalization, or all-cause mortality. Comparisons between treatment groups were obtained using the log-rank test statistic. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC). A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Role of the Funding Source

The sponsor funded the parent IPFnet clinical trials and their substudies, but had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the manuscript. The authors take full responsibility for the content of this article, contributed to data interpretation, amended the manuscript, and attest to the accuracy and completeness of the reported data. The lead authors were involved in the study design, analyses, and writing of the report.. KA, RR, and EY had full access to all of the raw data in the study. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

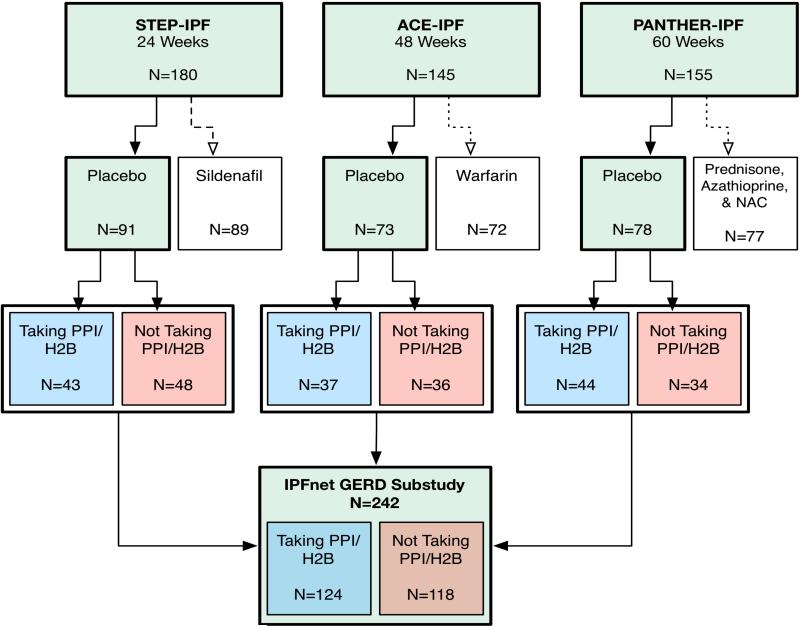

From September 2007 through October 2011, 480 patients with IPF were enrolled into IPFnet clinical trials (Figure 1). Among the 242 patients randomized to receive placebo therapy, 124 (51%) were taking either a PPI (n = 113) or H2B (n = 11) upon enrollment. No patients were taking both PPI and H2B. There were no significant differences in demographics, measures of disease severity (e.g., FVC %predicted and DLCO %predicted), and patient-reported outcome measures (e.g., symptom severity and quality of life) between patients taking PPI/H2B and those not taking PPI/H2B (Table 1). A higher percentage of patients taking PPI/H2B reported a history of sleep apnea and treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) compared to those not taking PPI/H2B (22% vs. 10%, p-value = 0.01). There were no differences between other non-GER related co-morbidities and PPI/H2B use. Patient characteristics by individual trial are included in the Supplementary Appendix (Tables S2-S4). In general, the baseline characteristics of all three trials were similar to the combined cohort, with the STEP-IPF cohort being more physiologically advanced than the other two cohorts as anticipated. The total follow-up time was 7079.43 weeks, with an average follow-up time of 29.25 weeks.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the three parent clinical trials (STEP-IPF, ACE-IPF, and PANTHER-IPF) and how patients were identified and categorized in this study.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients*

| Characteristic | Taking PPI/H2B (n=124) | Not taking PPI/H2B (n=118) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| STEP-IPF study – no. (%) | 43 /124 (35%) | 48 /118 (41%) | |

| ACE-IPF study – no. (%) | 37 /124 (30%) | 36 /118 (30%) | |

| PANTHER-IPF study – no. (%) | 44 /124 (35%) | 34 /118 (29%) | |

| Age – year | 68 ± 8 | 67 ± 9 | 0·62 |

| Female sex – no. (%) | 31 /124 (25%) | 21 /118 (18%) | 0·17 |

| Ever smoker – no. (%) | 93 /124 (75%) | 92 /118 (78%) | 0·59 |

| Body Mass Index – kg/m2 | 30 ± 5 | 30 ± 5 | 0·55 |

| Time since diagnosis – year† | 1·14 (0·52, 2·62) | 0·96 (0·31, 2·00) | 0·04 |

| Supplemental oxygen use – no. (%) | 31 /124 (25%) | 20 /118 (17%) | 0·13 |

| 6-Minute walk distance – m | 312·45 ± 131·41 | 296·01 ± 137·85 | 0·27 |

| Total score on St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (range, 0-100)‡ | 48·35 ± 16·95 | 46·12 ± 18·20 | 0·20 |

| Score on Shortness of Breath Questionnaire (range, 0-120)‡ | 38·25 ± 20·47 | 38·57 ± 23·34 | 0·97 |

| Forced vital capacity | |||

| % predicted | 64·08 ± 16·43 | 61·89 ± 15·59 | 0.39 |

| Liters | 2·55 ± 0·79 | 2·53 ± 0·75 | 0·96 |

| DLCO – % predicted | 33·62 ± 12·66 | 34·52 ± 13·61 | 0·66 |

| Medical Co-morbidities | |||

| GERD – no. (%) | 110 /124 (89%) | 30 /118 (25%) | <0·01 |

| Barrett's esophagus – no. (%) | 9 /81 (11%) | 1 /70 (1%) | 0·01 |

| Hiatal hernia – no. (%) | 24 /87 (28%) | 2 /71 (3%) | <0·01 |

| Fundoplication surgery – no. (%) | 6 /124 (5%) | 0 /118 (0%) | 0·03 |

| Sleep Apnea – no. (%) | 46 /124 (37%) | 16 /118 (14%) | <0·01 |

| Sleep Apnea with CPAP – no. (%) | 27 /123 (22%) | 12 /118 (10%) | 0·01 |

| Asthma – no. (%) | 8 /124 (7%) | 6 /118 (5%) | 0·65 |

| Diabetes – no. (%) | 26 /124 (21%) | 22 /118 (19%) | 0·65 |

| Coronary Artery Disease – no. (%) | 32 /124 (26%) | 22 /118 (19%) | 0·18 |

| Method of GERD diagnosis | |||

| Symptoms of heartburn – no. (%) | 76 /112 (68%) | 24 /80 (30%) | <0·01 |

| Barium swallow test – no. (%) | 9 /112 (11%) | 2 /80 (3%) | 0·06 |

| 24 hr pH monitoring – no. (%) | 17 /112 (20%) | 1 /80 (1%) | <0·01 |

| Endoscopy – no. (%) | 32 /112 (36%) | 4 /80 (6%) | <0·01 |

| Use of lifestyle changes – no. (%)§ | 62 /112 (50%) | 10 /80 (9%) | <0·01 |

| Medications¶ | |||

| PPI at baseline – no. (%) | 113 /124 (91%) | 0 /118 (0%) | <0·01 |

| H2B at baseline – no. (%) | 11 /124 (9%) | 0 /118 (0%) | <0·01 |

| Prednisone – no. (%) | 22 /124 (18%) | 22 /118 (19%) | 0·86 |

| Prednisone/Azathioprine/NAC – no. (%) | 7 /124 (6%) | 6 /118 (5%) | 0·85 |

STEP-IPF – Sildenafil Trial of Exercise Performance in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; ACE-IPF – Anticoagulant Effectiveness in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; PANTHER-IPF – Prednisone, Azathioprine, and N-Acetylcysteine: A Study that Evaluates Response in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; GERD – Gastroesophageal reflux disease; DLCO – carbon monoxide diffusing capacity; PPI/H2B – proton pump inhibitor/H2 blocker, CPAP – continuous positive airway pressure, NAC – N-Acetylcysteine

Plus-minus values are means ± SD. Some percentages may be impacted by missing data. The following variables had missing data: baseline Shortness of Breath Questionnaire (N=4), baseline St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (N=11), and baseline DLCO % predicted (N=3).

Values are median (25th and 75th percentile).

A higher score indicates worse function.

One or more of the following lifestyle changes: bed elevated, sleeping in recliner, limiting symptomatic food and beverage, avoid laying down flat for three hours after eating, avoid bedtime snacks, eating small meals

Baseline use of medications. This is not relevant to patients in the PANTHER study.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Specific Characteristics

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was reported in 89% of patients taking PPI/H2B and 25% of those not taking PPI/H2B (Table 1). There were also a higher percentage of patients taking PPI/H2B who reported a history of Barrett's esophagus and hiatal hernia. Most patients taking PPI/H2B were diagnosed based on symptoms of heartburn (68%). In general, GER characteristics by individual trial were similar to the combined cohort (Tables S2-S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

More patients taking PPI/H2B reported use of at least one lifestyle change to treat symptoms of GER compared to those not taking PPI/H2B (50% vs. 9%, p-value <0.01). Of the 124 patients who were on PPI/H2B at baseline, 117 (94%) continued to take a PPI/H2B for the entire study period. Of the 118 patients who were not on PPI/H2B at baseline, 19 (16%) started PPI therapy during the study period. Six patients had undergone fundoplication surgery for treatment of GERD prior to study enrollment; they were all taking PPI/H2B at baseline.

Change in Forced Vital Capacity

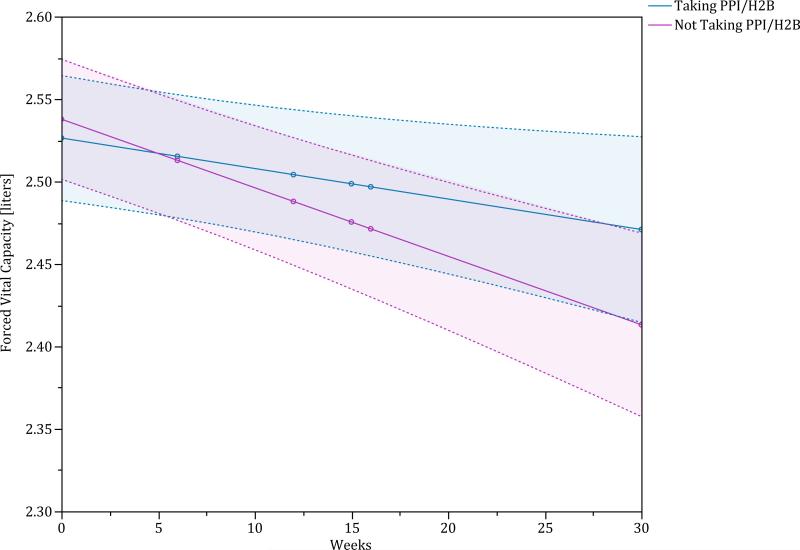

On unadjusted analysis, patients taking a PPI/H2B had a significantly smaller decline in FVC at 30 weeks (p-value = 0.01). Other variables that were significantly associated with decline in FVC change included sex, baseline FVC %predicted and baseline DLCO %predicted. After adjusting for these potential confounders, patients taking PPI/H2B at baseline continued to have a significantly smaller decline in FVC compared to those patients not taking a PPI/H2B at baseline (estimated difference between groups over 30 weeks of 0·07 liters (95% CI 0.00, 0.14), p-value = 0.05), (Figure 2, Figure S3 of the Supplementary Appendix). Study-specific analyses for change in FVC are provided in Figures S4-S6 of the Supplementary Appendix.

Figure 2.

Repeated measures estimate of change in forced vital capacity (liters) comparing those taking a PPI/H2B (blue line is point estimate and shaded blue region is the 95% confidence interval) and those not taking PPI/H2B (red line is point estimate and shaded red region is 95% confidence interval). This is adjusted for sex, baseline FVC %predicted, and baseline DLCO %predicted.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to better understand the relationship between PPI/H2B use and the decline in FVC (Table 2). Extending the follow-up time beyond the mean follow-up time of 30 weeks, the estimated change in FVC over 52 weeks was -0.09 liters (95% CI -0.18, -0.01) vs. -0.21 liters (95% CI -0.29, -0.13), p-value = 0.04, in those taking PPI/H2B at baseline compared to not. The association between PPI/H2B use and smaller decline in FVC remained qualitatively similar after adjusting for parent clinical trial (p-value = 0.05), excluding those taking H2B (p-value = 0.05), excluding those with acute exacerbation (p-value = 0.05), excluding those not taking PPI/H2B for the entire study duration (p-value = 0.05), excluding those in STEP-IPF (p-value = 0.07), and limiting data to less than 30 weeks from enrollment (p-value = 0.19).

Table 2.

Analysis of Change in Forced Vital Capacity Outcome*

| Change in Forced Vital Capacity -- liters | Estimated Change over 30 weeks with 95% Confidence Interval |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taking PPI/H2B | Not taking PPI/H2B | ||

| STEP-IPF/ACE-IPF/PANTHER-IPF | −0·06 (−0·11, −0·01) | −0·12 (−0·17, −0·08) | 0·05 |

| Estimated change over 52 weeks | −0·09 (−0·18, −0·01) | −0·21 (−0·29, −0·13) | 0·04 |

| 30 week estimate using only data <30 weeks from enrollment | −0·10 (−0·18, −0·03) | −0·17 (−0·23, −0·10) | 0·19 |

| With adjustment for study | −0·05 (−0·10, −0·00) | −0·12 (−0·17, −0·08) | 0·05 |

| Exclusion of those taking H2B | −0·05 (−0·10, 0·00) | −0·12 (−0·17, −0·08) | 0·05 |

| Exclusion of acute exacerbation | −0·05 (−0·11, 0·00) | −0·12 (−0·17, −0·08) | 0·05 |

| Exclusion of patients not taking PPI/H2B 100% of study duration | −0·05 (−0·10, 0·00) | −0·12 (−0·17, −0·08) | 0·05 |

| With adjustment for sleep apnea treatment | −0·06 (−0·11, −0·01) | −0·12 (−0·17, −0·08) | 0·05 |

| STEP-IPF | −0·06 (−0·21, 0·08) | −0·18 (−0·30, −0·06) | 0·22 |

| ACE-IPF | −0·04 (−0·13, 0·04) | −0·13 (−0·20, −0·06) | 0·11 |

| PANTHER-IPF | −0·06 (−0·13, 0·04) | −0·11 (−0·18, −0·05) | 0·27 |

| ACE-IPF and PANTHER-IPF | −0·05 (−0·11, 0·00) | −0·12 (−0·7, −0·07) | 0·07 |

STEP-IPF – Sildenafil Trial of Exercise Performance in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; ACE-IPF – Anticoagulant Effectiveness in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; PANTHER-IPF – Prednisone, Azathioprine, and N-Acetylcysteine: A Study that Evaluates Response in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; PPI/H2B – proton pump inihibitor/H2 blocker

Adjusted for sex, baseline forced vital capacity %predicted, and baseline carbon monoxide diffusing capacity %predicted.

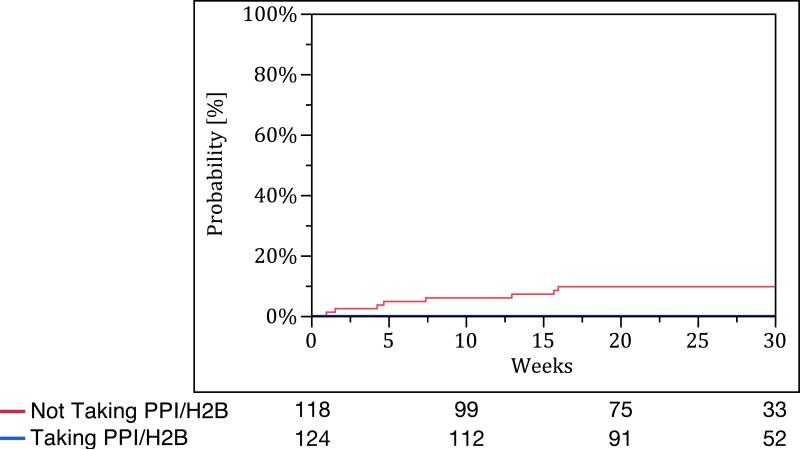

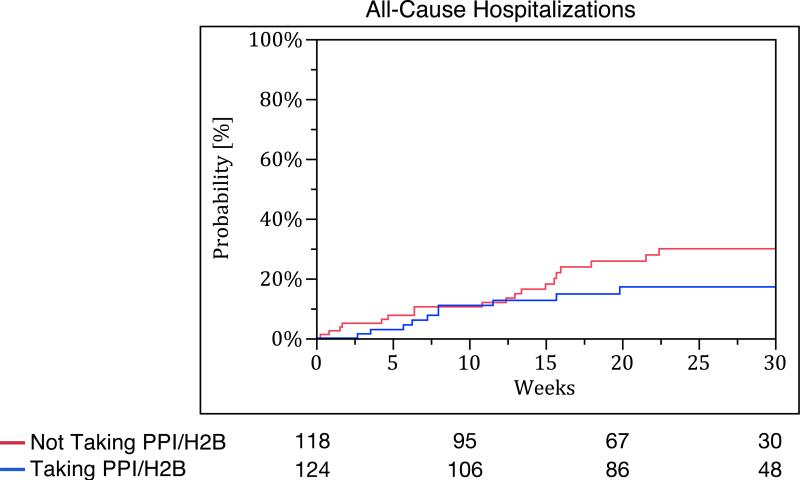

Secondary outcomes

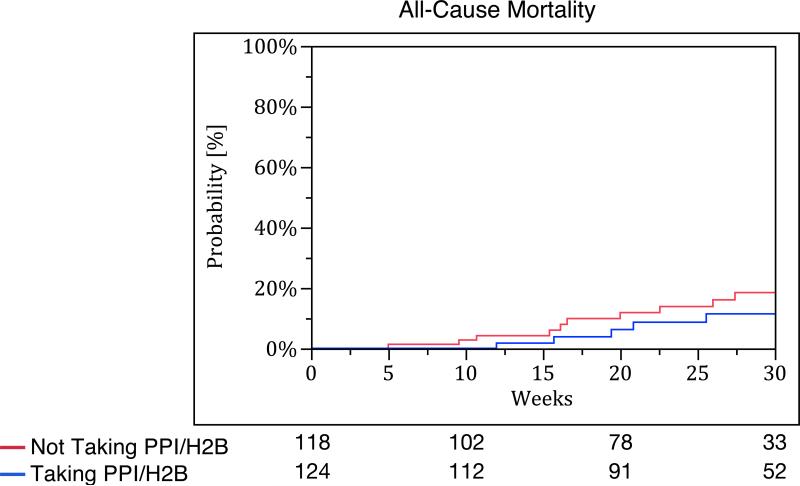

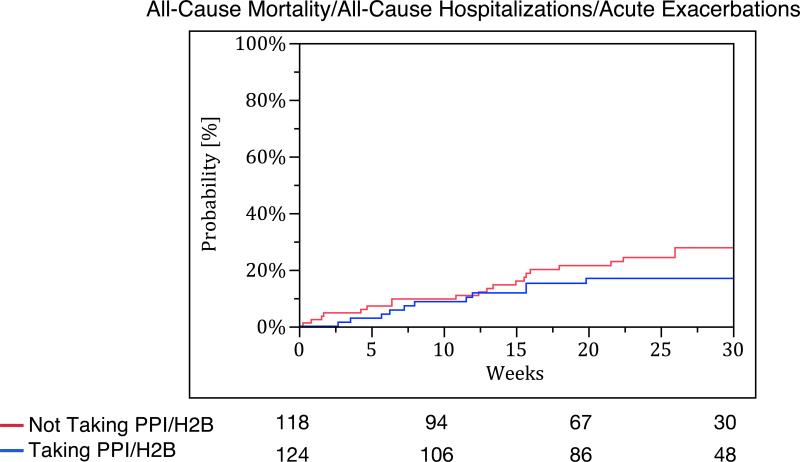

Patients taking PPI/H2B at baseline had fewer acute exacerbations compared to those not taking PPI/H2B at baseline (no events vs. nine events, p-value <0.01). However, there were no significant differences in time to all-cause hospitalization (p-value = 0.18), all-cause mortality (p-value = 0.12), and the composite endpoint of acute exacerbation, all-cause hospitalization, or all-cause mortality between the groups (p-value = 0.40) (Figure 3). Study-specific analyses for these endpoints are provided in Table S5 of the Supplementary Appendix.

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier survival curves for (A) acute exacerbation, (B) all-cause hospitalization, (C) all-cause mortality, and (D) combined endpoint of acute exacerbation, all-cause hospitalization, and all-cause mortality. The blue line represents those taking PPI/H2B and the red line represents those not taking PPI/H2B.

There were no significant differences in change in 6MWD, change in dyspnea score, and change in quality of life between the two groups (Table S6 of the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

This study used prospectively designed and administered data collection methodology to demonstrate a significantly slower decline in FVC over time in well-defined IPF patients taking PPI and/or H2B than in those not taking these therapies. Decline in FVC has been correlated with shorter survival time in IPF,(18-21) and is considered a measure of disease progression.(2) Our findings, therefore suggest that anti-acid therapy is beneficial in patients with IPF and support the hypothesis that abnormal acid GER is important to disease progression.(22)

There were no episodes of adjudicated acute exacerbation in patients receiving anti-acid therapy. The observation of fewer acute exacerbations in those taking anti-acid therapy is novel and clinically significant.(23, 24) However, a reduction in acute exacerbations is not the explanation for the smaller decline in FVC seen in the PPI/H2B group, since the same changes in FVC were observed when patients experiencing acute exacerbation were excluded from the analysis. This suggests that microaspiration of gastric acid may contribute to disease progression with or without acute exacerbation. While reports of two phase II clinical trials of novel therapies demonstrated a reduction in episodes of acute exacerbations, these events were not confirmed by central review as they were in the IPFnet trials.(6, 25) One of these therapies, pirfenidone, was not associated with a reduction in acute exacerbations in the subsequent phase III clinical trials.(25) A phase III trial of the other agent, BIBF 1120, is ongoing.

We did not observe an effect on mortality in this study. A large retrospective analysis of anti-acid therapy use in patients with IPF suggested that patients taking PPI/H2B was associated with longer survival time and less radiologic fibrosis.(16) The current study focused on change in FVC and was not adequately powered to find an association with mortality. We believe this is most likely due to the limited mean follow-up time of 30 weeks (compared to 2.21 years in the retrospective cohort study). Although there is no statistically significant difference between the groups, our data is consistent with improved survival in those taking anti-acid therapy.

The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was higher in those taking PPI/H2B compared to those who were not. Obstructive sleep apnea is common in IPF.(26) In addition, OSA has been associated with increased nocturnal GER(27, 28) and the treatment of OSA with CPAP has been shown to reduce the frequency of nocturnal GER.(27, 29) The mechanism for increased GER due to OSA may be due to weakening of the lower esophageal sphincter from repetitive strain associated with increased intra-thoracic pressure during obstructed breathing events.(30) In this cohort, sleep apnea was strongly associated with PPI/H2B use; however, OSA was not associated with change in FVC. Adjustments for OSA did not change the association between PPI/H2B use and slower decline in FVC. Whether the treatment of OSA can provide additional benefit to PPI/H2B therapy is unknown.

Although the data on PPI/H2B use was prospectively collected at each study visit, this is not a randomized controlled trial of PPI/H2B therapy in IPF. In addition, we do not know the duration of anti-acid therapy before study enrollment. Therefore, there may be unmeasured confounders that are impacting the relationship between PPI/H2B use and outcomes. Controlling for measured factors in the dataset however, did not alter the association. The placebo arms of three IPFnet trials were combined in order to increase the power and generalizability of our study. Importantly, the results remain consistent when analyzed by individual study and when STEP-IPF patients, a cohort with more advanced disease, are excluded. In all of the patients, the presence of abnormal acid GER and the suppression of acid GER in those taking PPI/H2B were not confirmed by ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH and/or impedance monitoring. Therefore, there is a possibility of unequal distribution of pathologic GER in the PPI/H2B-treated and -untreated groups and this may be a source of bias. However, based on previously published data, the prevalence of pathologic GER in IPF is thought to be up to 90 percent, with only a minority of patients reporting typical symptoms of GER.(9-11) Unlike surgical therapy for GER, anti-acid therapy does not prevent reflux from occurring and simply decreases the acidity of the gastric contents.(31) These data do not provide any information on whether surgical therapy for reflux might be superior to medical therapy for GER. Given the design and purpose of this study, these data also do not provide an explanation for the mechanism of action of PPI/H2B therapy in slowing disease progression in IPF.

Anti-acid treatment in patients with IPF epitomizes a well-known aphorism in medicine: “Prevention is better than cure.” Most drugs being tested in IPF aim to slow disease progression by targeting fibroproliferation, synthesis and deposition of extracellular matrix in the lung. In addition, most clinical trials in IPF have not demonstrated any beneficial effect on clinically meaningful outcomes such as acute exacerbation. Treatment with anti-acid therapy, if effective, would be unique in that its presumed mechanism of action would be through the prevention of further insults to the IPF lung (and therefore reducing further stimulus for fibroproliferation). While a randomized controlled clinical trial of medical and/or surgical therapy for GER in IPF is warranted based on these encouraging results, we recognize the challenges of such a trial given the widespread availability of anti-acid therapy. However, given the potential risks of long-term anti-acid therapy (e.g. infection, electrolyte malabsorption, and drug interactions (32-36)), confirmation of these results in a definitive, randomized controlled trial are essential.

Panel: Research in Context

Systematic Review

We searched PubMed with the search term “(gastroesophageal reflux treatment OR anti-reflux treatment OR proton pump inhibitor OR microaspiration) AND idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.” No date or language restrictions were applied. The search identified 42 publications. Of these, five articles contained original data on anti-reflux treatment in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.(13, 14, 16, 37, 38) Four of the five articles were case reports or small case series.(13, 14, 37, 38) The fifth article was a retrospective, two-center cohort study investigating patient reported anti-reflux medication use and transplant-free survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.(16) The remaining articles were reviews, editorials, letters to the editor, or did not assess the effect of anti-reflux treatment in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. These previous studies suggested that anti-reflux treatment, both medical and surgical, was associated with improved outcomes in patients with IPF. The aim of this study was to determine the association between anti-acid therapy and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis using prospectively collected data from case report forms designed specifically to capture the data regarding GER and treatment for GER.

Interpretation

Our study substantially extends upon previous retrospective work by prospectively investigating the effect of anti-reflux therapy across the placebo arms of the three IPFnet randomized controlled trials. The results of this study demonstrating that anti-reflux therapy is associated with a reduction on the rate of physiological decline and fewer acute exacerbations in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are striking. Considering that clinical trials of anti-inflammatory and novel anti-fibrotic agents have failed to consistently demonstrate a safe and efficacious treatment regimen for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,(5, 7, 39) our findings strongly support the development of controlled clinical trials of anti-reflux therapies in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

ASSURANCES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to the faculty, staff, and patients at all participating IPFnet medical centers.

Funding: The IPFnet and its projects are funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and The Cowlin Family Fund at the Chicago Community Trust. This substudy was supported by grant: NIH/NCRR/OD UCSF-CTSI KL2 RR024130.

Footnotes

All authors assume responsibility for the overall content and integrity of the article.

Author Contributions

JSL, HRC and GR contributed to all aspects of the manuscript. KJA contributed to the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, editing and approval; FJM to the writing, editing, and approval; IN to the study design, data interpretation, and writing, editing, and approval; RSR to the figures, study design, data analysis, interpretation, and writing; and EY to the figures, study design, data analysis, interpretation, and writing.

Conflicts of Interest

Harold R. Collard: Consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim, FibroGen, Genentech, Gilead, Medimmune, and Promedior; Fernando J. Martinez: Participated in advisory boards covering COPD or IPF topics for Able Associates, Actelion, Almirall, Bayer, GSK, Ikaria, Janssen, MedImmune, Merck, Pearl, Pfizer and Vertex; consulted on COPD or IPF topics for American Institute for Research, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Carden Jennings, Cardiomems, Grey Healthcare, HealthCare Research and Consulting, Janssens, Merion, Nycomed/Takeda, and Sudler and Hennessey; a steering committees member for studies sponsored by Actelion, Centocor, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead, Mpex, Nycomed/Takeda; participated in Food and Drug Administration mock panels for Boehringer Ingelheim, Forest and GSK; served on speaker's bureaus or in continuing medical education activities sponsored by American College of Chest Physicians, American Lung Association, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, William Beaumont Hospital, Boehringer Ingelheim, Center for Health Care Education, CME Incite, Forest, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Lovelace, MedEd, MedScape/WebMD, National Association for Continuing Education, Network for Continuing Medical Education, Nycomed/Takeda, Projects in Knowledge, St Luke's Hospital, the University of Illinois Chicago, University of Texas Southwestern, University of Virginia, UpToDate; served on DSMBs for Biogen and Novartis; and received royalties from Castle Connolly and Informa. The University of Michigan received funds from the National Institutes of Health for COPD and IPF studies; Imre Noth: Consulted for ImuneWorks; has contracts with Stromedix, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Asthmatx; received funding from the National Institutes of Health; and has patents pending in the prognosis of IPF (mRNA, MMP7, and GWAS); and Ganesh Raghu: Received funding and pending grants from NIH; Consulted for Actelion, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead, Fibrogen, Centocor (Johnson and Johnson), Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Promedior, Stromedix and Takeda; has given expert testimony to the U.S. Department of Justice; received royalties from UpToDate; and travel to discuss management of IPF was arranged by Intermune-EU The University of Washington received funds to conduct IPF studies from the National Institutes of Health.

The other authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bjoraker JA, Ryu JH, Edwin MK, et al. Prognostic significance of histopathologic subsets in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998 Jan;157(1):199–203. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9704130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Mar 15;183(6):788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zisman DA, Schwarz M, Anstrom KJ, Collard HR, Flaherty KR, Hunninghake GW. A controlled trial of sildenafil in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 12;363(7):620–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noth I, Anstrom KJ, Calvert SB, et al. A placebo-controlled randomized trial of warfarin in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012 Jul 1;186(1):88–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0314OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE, Jr., Lasky JA, Martinez FJ. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012 May 24;366(21):1968–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richeldi L, Costabel U, Selman M, Kim DS, Hansell DM, Nicholson AG, et al. Efficacy of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2011 Sep 22;365(12):1079–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet. 2011 May 21;377(9779):1760–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King TE, Jr., Brown KK, Raghu G, et al. BUILD-3: a randomized, controlled trial of bosentan in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Jul 1;184(1):92–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1874OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobin RW, Pope CE, 2nd, Pellegrini CA, Emond MJ, Sillery J, Raghu G. Increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998 Dec;158(6):1804–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9804105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweet MP, Patti MG, Leard LE, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis referred for lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007 Apr;133(4):1078–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raghu G, Freudenberger TD, Yang S, et al. High prevalence of abnormal acid gastrooesophageal reflux in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2006 Jan;27(1):136–42. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00037005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raghu G, Meyer KC. Silent gastro-oesophageal reflux and microaspiration in IPF: mounting evidence for anti-reflux therapy? Eur Respir J. 2012 Feb;39(2):242–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00211311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghu G, Yang ST, Spada C, Hayes J, Pellegrini CA. Sole treatment of acid gastroesophageal reflux in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a case series. Chest. 2006 Mar;129(3):794–800. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linden PA, Gilbert RJ, Yeap BY, et al. Laparoscopic fundoplication in patients with end-stage lung disease awaiting transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006 Feb;131(2):438–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JS, Song JW, Wolters PJ, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage pepsin in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2011 Dec 19; doi: 10.1183/09031936.00050911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JS, Ryu JH, Elicker BM, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux therapy is associated with longer survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Dec 15;184(12):1390–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0138OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collard HR, Moore BB, Flaherty KR, et al. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Oct 1;176(7):636–43. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-463PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collard HR, King TE, Jr., Bartelson BB, Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Brown KK. Changes in clinical and physiologic variables predict survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Sep 1;168(5):538–42. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1311OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flaherty KR, Mumford JA, Murray S, et al. Prognostic implications of physiologic and radiographic changes in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Sep 1;168(5):543–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200209-1112OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latsi PI, du Bois RM, Nicholson AG, et al. Fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: the prognostic value of longitudinal functional trends. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Sep 1;168(5):531–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1245OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King TE, Jr., Safrin S, Starko KM, et al. Analyses of efficacy end points in a controlled trial of interferon-gamma1b for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2005 Jan;127(1):171–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JS, Collard HR, Raghu G, et al. Does chronic microaspiration cause idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Am J Med. 2010 Apr;123(4):304–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blivet S, Philit F, Sab JM, et al. Outcome of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis admitted to the ICU for respiratory failure. Chest. 2001 Jul;120(1):209–12. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez FJ, Safrin S, Weycker D, et al. The clinical course of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Jun 21;142(12 Pt 1):963–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-12_part_1-200506210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azuma A, Nukiwa T, Tsuboi E, et al. Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Trial of Pirfenidone in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 May 1;171(9):1040–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-571OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lancaster LH, Mason WR, Parnell JA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is common in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2009 Sep;136(3):772–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green BT, Broughton WA, O'Connor JB. Marked improvement in nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux in a large cohort of patients with obstructive sleep apnea treated with continuous positive airway pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Jan 13;163(1):41–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ing AJ, Ngu MC, Breslin AB. Obstructive sleep apnea and gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. 2000 Mar 6;108(Suppl 4a):120S–5S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerr P, Shoenut JP, Millar T, Buckle P, Kryger MH. Nasal CPAP reduces gastroesophageal reflux in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1992 Jun;101(6):1539–44. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shepherd K, Hillman D, Holloway R, Eastwood P. Mechanisms of nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux events in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2011 Sep;15(3):561–70. doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raghu G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: increased survival with “gastroesophageal reflux therapy”: fact or fallacy? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Dec 15;184(12):1330–2. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201110-1842ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwok CS, Arthur AK, Anibueze CI, Singh S, Cavallazzi R, Loke YK. Risk of Clostridium difficile infection with acid suppressing drugs and antibiotics: meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Jul;107(7):1011–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar M, Hennessy S, Yang YX. Proton-pump inhibitor use and the risk for community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Sep 16;149(6):391–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-6-200809160-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eom CS, Jeon CY, Lim JW, Cho EG, Park SM, Lee KS. Use of acid-suppressive drugs and risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2011 Feb 22;183(3):310–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.092129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hess MW, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, Drenth JP. Systematic review: hypomagnesaemia induced by proton pump inhibition. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012 Sep;36(5):405–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khalili H, Huang ES, Jacobson BC, Camargo CA, Jr., Feskanich D, Chan AT. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of hip fracture in relation to dietary and lifestyle factors: a prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauret J, Casan P. [The association of diffuse pulmonary fibrosis and hiatal hernia: a simple coincidence? (author's transl)]. Med Clin (Barc) 1980 Mar 25;74(6):235–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dipaola F, Galli A, Selmi C, Furlan R. Efficacy of medical therapy in a case of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis due to gastroesophageal reflux disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2009 Dec;4(6):535–7. doi: 10.1007/s11739-009-0301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raghu G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: new evidence and an improved standard of care in 2012. Lancet. 2012 Aug 18;380(9842):699–701. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.