Abstract

PURPOSE

To test for the ability of different MRI modalities to discriminate the time course of damage and regeneration in a model of acute, toxin-induced muscle damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analyzed the time course of tissue and cellular changes in mouse lower limb musculature following localized injection of myotoxin by T2, magnetization transfer (MT) and diffusion weighted MRI. We also used T1 weighted imaging to measure leg muscle volume. In addition, post-mortem histological analysis of toxin-injected muscles was compared to uninjected controls.

RESULTS

The damages detected by the MRI modalities are transient and recover within 3 weeks. Muscle water diffusivity and edema measured by leg volume increased within the first hours after injection of the toxin. The rate constant for volume increase was 0.65 ± 0.11 hr−1, larger than the increase in T2 (0.045 ± 0.013 hr−1) and change in MT ratio (0.028 ± 0.021 hr−1). During repair phase, the rate constants were much smaller: 0.022 ± 0.004 hr−1, 0.013 ± 0.0019 hr−1 and 0.0042 ± 0.0016 hr−1 for volume, T2 and MT ratio, respectively. Histological analyses confirmed the underlying cellular changes that matched the progression of MR images.

CONCLUSION

The kinetics of change in the MRI measurements during the progression of damage and repair shows MRI modalities can be used to distinguish these processes.

Keywords: Skeletal muscle, MRI, necrosis, regeneration, myotoxin

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (1,2) can detect pathological changes at the cellular and tissue level in skeletal muscle because it probes different aspects of the spin properties of 1H in tissue water that are affected by the physiological and pathological status of the tissue. These imaging methods provide information on morphology, T1 and T2 relaxation (3–9), diffusion (8,10–12) and magnetization transfer effects (13–16). T2 weighted (T2w) sequences are commonly used to evaluate muscle disorders (13, 14). Similar studies analyzing T2 and diffusion tensor images documented time-dependent changes in muscle after denervation (17). Magnetization transfer contrast (MTC) imaging quantified progression of disease in patients with limb girdle muscular dystrophy (18). Mattila et al. (15) used MTC, T1 weighted (T1w) and T2w imaging to monitor the time course of necrosis and regeneration in rat leg muscle following injection of the myotoxin, notexin. This myotoxin damages mature muscle cells but spares the satellite cells and muscle cell basement membranes (19). Full regeneration and restoration of function occurs in about three weeks. All of these examples demonstrate pathological changes in muscle lead to substantial changes in one or more of these MRI parameters.

Our work compared T1w, T2w, diffusion weighted and MTC imaging followed by histological analysis to evaluate their sensitivity to muscle damage and regeneration in a mouse model of acute, myotoxin (BaCl2) induced muscle damage. This allowed us to test for the ability of different imaging modalities to discriminate the time course of sequential changes during the damage and necrosis phase as well as during the proliferation and regeneration phases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Sixteen eight week old male C57Bl/6 mice were housed with access ad libitum to standard mouse chow and water with 12:12 light cycle at ambient temperature 72 – 74°F until the morning of the experiment. Mouse husbandry and procedures were performed in accord with the National Institute of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals and with approvals from our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Anesthesia and muscle injury

Anesthesia was induced by inhalation of 5% isoflurane in oxygen and maintained by 1.5% isoflurane in oxygen via a nose cone during injection of the myotoxin. There were 2 separate injections (each of 50 µL of 0.125 M BaCl2), one into the anterior compartment and the other into the posterior compartment of the lower leg in the vicinity of the tibialis anterior (TA) and gastrocnemius (GA) muscles. In 14 mice one leg was injected and the other leg served as a control. For pain control, ibuprofen (40 mg/mL water) was incorporated into the drinking water for five days starting on the day of injection. The animals were returned to their cages after recovery from anesthesia and monitored daily.

Animals were studied on various days after toxin injection until recovery at 3 weeks to obtain images of the events occurring during necrosis, inflammation, cellular proliferation and infiltration and regeneration. Of the 16 mice, 14 mice were used for MRI on multiple days; Table 1 provides the details. Two mice were imaged only once following toxin injection and two mice were imaged almost daily, according to the schedule given in Table 1. For day 0, within 4 hours of toxin injection, the animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and restrained on a holder with the legs in a fixed position within the MR coil and imaged. On the other days and on a number of days until three weeks after the injection of myotoxin the animals were re-anesthetized and imaged in the same manner. A circulation of warm water in a water jacket maintained body temperature. Animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation while anesthetized to harvest samples for histological analyses at specific days after the last time points of MR imaging. All procedures were recorded by hours and day, so that the time course of the results could be described by the number of hours from the injection of myotoxin to the midpoint of the imaging session for quantitative analyses of time courses.

Table 1.

Animal information for quantitative MRI measurements conducted on dates marked with ‘x’

| Multiple | Single | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Jan L |

Jan R |

M21 A |

M2 1B |

M21 C |

Sep L |

Sep N |

Apr M3 |

Apr M4 |

M5 A |

M5 B |

M7 A |

M7 B |

M7 C |

M3 FJ |

M3 B |

| 0 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 2 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 3 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| 4 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| 6 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 7 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 8 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | ||||||||||||||||

| 10 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| 11 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 13 | ||||||||||||||||

| 14 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 15 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 16 | ||||||||||||||||

| 17 | ||||||||||||||||

| 18 | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| 19 | ||||||||||||||||

| 20 | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 21 | x | |||||||||||||||

MR apparatus

We used a 30 cm Bruker 4.7 Tesla (T) magnet with an INOVA 200 spectrometer (Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) with gradient strength of 100 mT/m (Bruker Corp., MA, model BGA-20-S2). The coil was a 25 mm Doty Scientific proton coil (Doty Scientific, SC, Litzcage 25 mm ID). MR pulse sequences specified in Table 2 were used to obtain 10 to 15, 1-mm thick image slices from above the ankle joint to the knee. Landmarks in the ankle and knee were used to make registrations of similar regions in serial images both in the injected and control legs. Most of parametric images acquired in this study used the field of view of 30 × 30 mm2 and a matrix size of 256 × 128 pixels while 3 dimensional (D) images for volume measurements used the field of view of 30 × 30 × 40 mm3 and matrix size of 128 × 64 × 64.

Table 2.

Mouse MR protocols

| Purpose | Sequence Type |

TR/TE (ms) | Acq. Time | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scout imaging | GRE | 30/1.3 | ~ 5 sec | 3 orthogonal images |

| Image planning | GRE | 500/3 | ~ 1 min | Slice position and orientation selected. |

| T1w | SE | 500/13 | 1 min | Lipid suppression with damaged regions slightly dark. |

| T2 | SE | 2000/13, 30, 60 | 24 min | T2 maps to visualize T2 changes between normal and affected regions. |

| Diffusion | SE | 2000/45, b=0, 573, 1123 s/mm2 | 24 min | ADC maps to visualize changes with tissue and cellular edema. |

| MT | GRE | 300/5 ms, θ = 20° for both with and without MT effect | 2 min | MT maps to emphasize myofibrillar destruction and regeneration, and other macromolecular changes. |

| 3D imaging | GRE | 100/3, θ = 10° | 14 min | To measure muscle volume. |

Abbreviations Used: TR: repetition time; TE: echo time; Acq. Time: Acquisition Time; GRE: Gradient Echo; SE: Spin Echo; T1w: T1 weighted; ADC: Apparent Diffusion Coefficient; MT: Magnetization Transfer; θ: flip angle.

T1 and T2 imaging

We performed quantitative T2 measurements using T2 maps generated by a spin echo sequence with three echo times of 13, 30 and 60 ms for mice at 4.7T. T1 and T2 weighted imaging was used to qualitatively visualize damaged regions in injected mouse leg muscles (and comparable regions in the control un-injected leg) based on parameters summarized in Table 2. An agarose sample (1% agarose in deionized water) was located next to the imaging region of interest on the animal leg to create standard T2 values when T2 acquisitions were conducted. T2 values measured by these sequences were validated by comparing muscle T2 values at different imaging time points with those for normal animals and by evaluating T2 values from the standard agarose sample to confirm the consistency of MR experimental settings at different time points of acquisitions.

Diffusion and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Maps

1H nuclei that move during the diffusion sequence cause an attenuated signal by random translational (or Brownian) motion of water molecules in tissues (22,23). Thus this MR modality is sensitive to molecular motion of water in the tissue. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were generated by diffusion weighted images acquired with three gradient intensities (b values of 0, 573 and 1123 s/mm2) incorporated in a spin echo sequence (TR/TE = 2 s/45 ms). We used the conventional Stejskal-Tanner (24) spin echo pulse sequence with two diffusion gradient pulses of length of 14 ms. The time interval between the two gradient pulses was 21 ms. The diffusion gradients were oriented perpendicular to axial imaging planes and along the direction for most fibers of hindlimb muscles. ADC values were calculated by fitting the signal intensity with the three b values, where s0 is signal intensity with b = 0. S0 is the initial intensity and s(b) is the intensity as a function of b values (2).

Magnetization Transfer Contrast

We measured MT suppression ratios defined by the following formula: (SI0 – SIs)/SI0, where SI0 is the signal intensity of tissue without the saturation pulse application and SIs is the signal intensity with the saturation pulse. Off-resonance frequency of 2000 Hz was determined to give the largest MT suppression ratio measured in uninjured muscle: the shape, width and power of the saturation pulse were sinc (with 4 zero crossings), 10 ms and 38.5 dB (in comparison to power 16.9 dB of main gradient echo RF pulse with its sinc shape and 2 ms width), respectively. This offset was used for all acquisitions during the time course of damage and regeneration to obtain the time course of changes in the leg muscles. For each presaturation pulse, spoiling gradients were applied along three orthogonal gradients with a duration of 4 ms and strength of 30 mT/m.

Volume Imaging

We did not identify specific muscles. Rather, we selected entire leg muscles with leg bones (tibia and fibula) excluded. T1 weighted gradient echo sequence was used to acquire a 3 dimensional image for the leg with parameters described in Table 2. The boundaries of the leg muscle were drawn for each slice and its volume measured. The volume of the leg was the sum of the volumes of all of the slices from a 3 dimensional image. The volumes of the regions of altered MRI properties were several times larger than the injected volume of 50 µL.

Data presentation

T2, ADC, and MT ratio maps were created using ImageJ software (version 1.44; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) with MRI Analysis Calculator plugin. Multi-slice MR images covered most of the affected muscle volume of interest. For the multi-slice imaging, we employed between 10 and 15 slices with 1 ~ 1.5 mm slice thickness and 0.2 ~ 0.5 mm slice gap depending on muscle volumes of interest. After review of the images from a given animal, one slice that was taken on different days was selected to achieve anatomic similarity for all others. Regions of interest were selected for both the anterior and posterior compartments of leg muscles giving measurements of each modality in each muscle compartment. A comparable region was selected from the contralateral (un-injected) leg to obtain control images in un-injected legs. Quantitative parameter maps of T2, ADC and MT suppression ratio were generated from the acquired MR parametric images. T2 imaging identified regions of interest for tissue histology. After necropsy, the tissue in that region was removed and processed. We obtained 10 regions with 100 micron separation along the long axis of the leg, each with two consecutive 10 micron thick slices.

To test the hypothesis that each imaging modality is sensitive to different properties of the evolving tissue and cellular changes during the evolution of damage and necrosis as well as during regeneration we grouped all MR images. Using the quantitative MR parameter maps, the average values and standard deviations for all pixels in the slices were calculated. For each imaging modality the percent difference between the summed intensity in the regions of interest (ROI) in affected and unaffected, control in the opposite leg, were calculated for each time point and used for quantifying magnitude and time course of the changes in MRI. For these we compared the differences between the experimental and control ROI’s ((Exp – Cont)/Cont) for volume, for T2, for ADC and for MT suppression ratio. We averaged the data at common times and from both compartments in each animal. These time- and animal-averaged data were fitted in two sections to exponential curves by regression analyses. The data were fitted to the equation: relative intensity at time t = initial intensity + (plateau − initial intensity)•(1−exp(−K•t)) where K is the rate constant. Curve fitting and statistical comparisons were made using PRISM software package V4 (www.graphpad.com).

Pathology

Necropsy, tissue sampling, processing, and histologic examination were done within ten minutes of ending the MRI session by removing the control and injected legs at the level of the greater trochanter. The severed legs were placed into fixative (10% formalin solution, neutral buffered from Sigma Aldrich, product HT501320) after the skin had been removed, stored in a refrigerator for 1 week, and another week at room temperature. Following conventional procedures and decalcification, cross sections were cut near the middle of the affected region of the MRI signal changes. Ten serial sections were cut and alternative ones were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Masson’s trichrome and examined in consultation with a pathologist. Some of the tissues (16% of all histology slides) were excessively decalcified: these gave staining artifacts and were not used. The results described here were made on slides judged adequately with the findings verified in muscle sections of the same muscle.

RESULTS

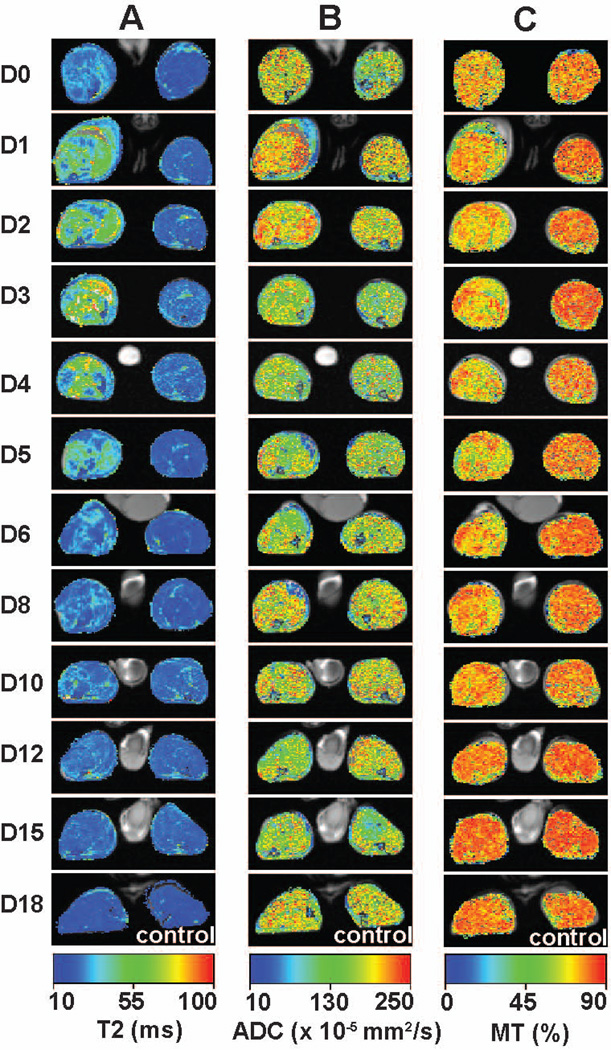

The images in Figure 1 display the temporal evolution of MR parameters (T2, ADC and MT ratio) in one animal studied frequently from day of injection through day 18 of recovery. There is a clear separation between the evolution of MR image changes during damage and necrosis to about day 5 and regeneration thereafter, as expected because the underlying cellular processes are so different. Panel A shows a series of T2 spin echo maps that demonstrate peak damage occurs within a few days and recovery is well underway by day 8. Figure 1 also displays ADC (Panel B) and MT ratio (Panel C) maps at approximately the same cross section of the limb during the evolution of damage and recovery. The T2 maps had the highest signal to noise which decreased in the order: T2 > MT > ADC. On inspection, the time course of the changes in the three imaging modalities appears slightly different both during the damage and necrosis phases and during regeneration. The water diffusivity, obtained from the ADC images, is maximal on the day of injection and decreases thereafter whereas the intensity of T2 and MT peak later. T2 changes are maximal on day 3 whereas the MT effects are maximal on days 4 and 5.

Figure 1.

Time course changes of T2 (Column A), ADC (Column B) and MT ratio (Column C) in quantified images for a single mouse (animal Jan L from Table 1). Colorized parameter maps were overlaid on their corresponding anatomic images. D0 through D18 represents the days of image acquisition after myotoxin injection. All parameter values are scaled absolutely.

Control values of parameters T2, ADC and MT ratio measured on un-injected legs for all mice at different days were 23.2 ± 0.3 ms (N = 63), (1.63 ± 0.04) × 10−3 mm2/s (N = 61) and 82.5 ± 0.2 % (N = 62), respectively. The values were described by mean, standard error of the mean and sample size (or total number of measurements) N.

Quantitative Analyses of time course of MRI changes

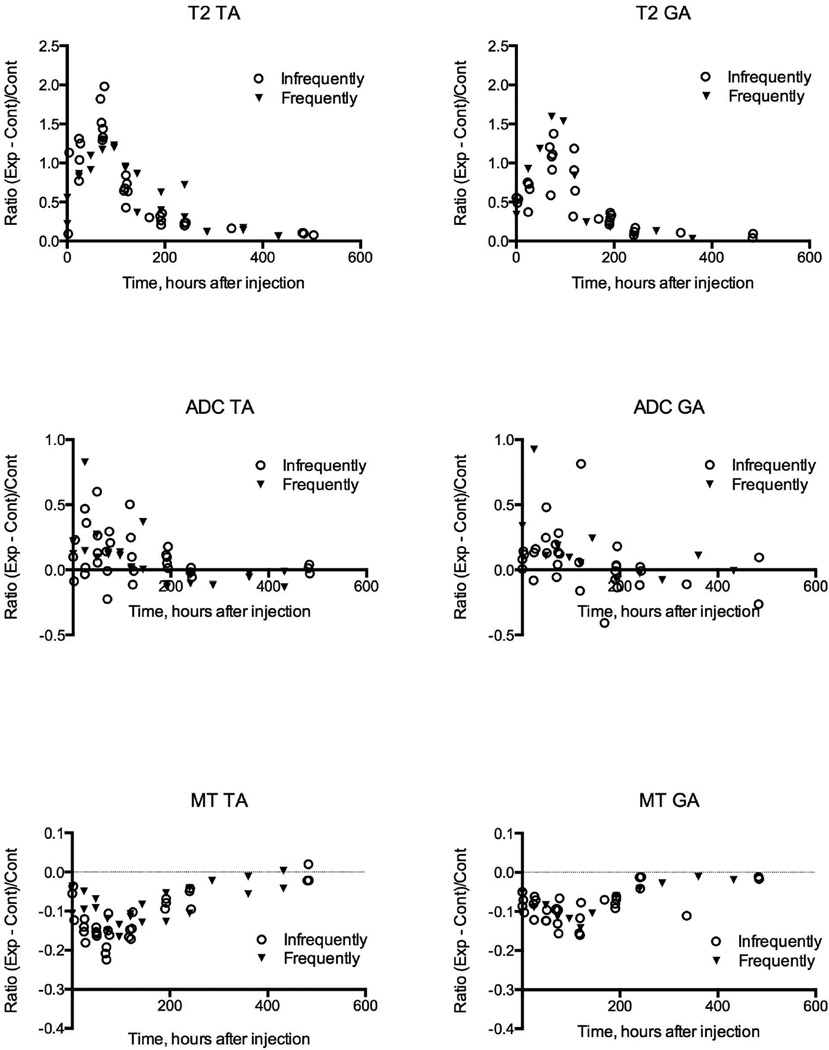

We grouped all MR images collected from 16 animals (Table 1). All data is plotted individually in Figure 2. Data, noted as a circle (infrequently), were grouped and averaged. The other data, identified by an upside down triangle (frequently) were obtained daily at the earlier time points post myotoxin injections and once every several days at the later time points for two mice noted as Jan L and Jan R in Table 1. Each data point represents the parametric image intensity in defined regions of interest in the same animal; corresponding regions in the control limb were analyzed in the same way. Each datum from the MR parametric maps of injected muscle was normalized to its corresponding control in the opposite leg by calculating the difference, experimental minus control value, and dividing that difference by the control value. Graphs of the results for all days and animals studied as a function of time since injection are given in Figure 2; the results from the images shown in Figure 1 are included. The abscissas are given in hours, rather than days, because we accurately recorded the time of injection of the toxin and time of imaging; the times given represent the hours from injection to mid-point of the MR imaging session. Graphs of the data showed there were no apparent differences between the data from the anterior and posterior compartment muscles in each animal. Results from both compartments were averaged in the same animal for further analyses.

Figure 2.

Graphs of quantified image intensities for three modalities (T2, ADC and MT) for all images obtained in this study. The graphs on the left columns are for tibialis anterior (TA) muscles and those on the right columns for gastrocnemius (GA) muscles. Data acquired infrequently were grouped and averaged as described in Results section and were noted as a circle. The other data obtained frequently were identified by an upside down triangle. Abscissa represents time in hours from the injection of myotoxin. Coordinates represent relative intensity compared to control values calculated as the ratio: (Exp − Cont)/Cont. There is a decrease in signal to noise: T2 > MT > ADC.

The changes in parametric maps shown in Figure 1 are verified by these quantitative data. Although there is considerable scatter in the data for ADC, it is clear that largest effects are seen very early, from the first day, and decline thereafter. The T2 changes peak about 80 to 100 hours whereas the peak MT effects peak somewhat later, about 90 to 120 hours.

Also the data obtained by multiple images in two animals (data from one shown in Figure 1) are separately marked, and are not distinguished from the others. Therefore the multiple imaging sessions and anesthesia had no detectable effect on the processes in the muscles during damage and regeneration.

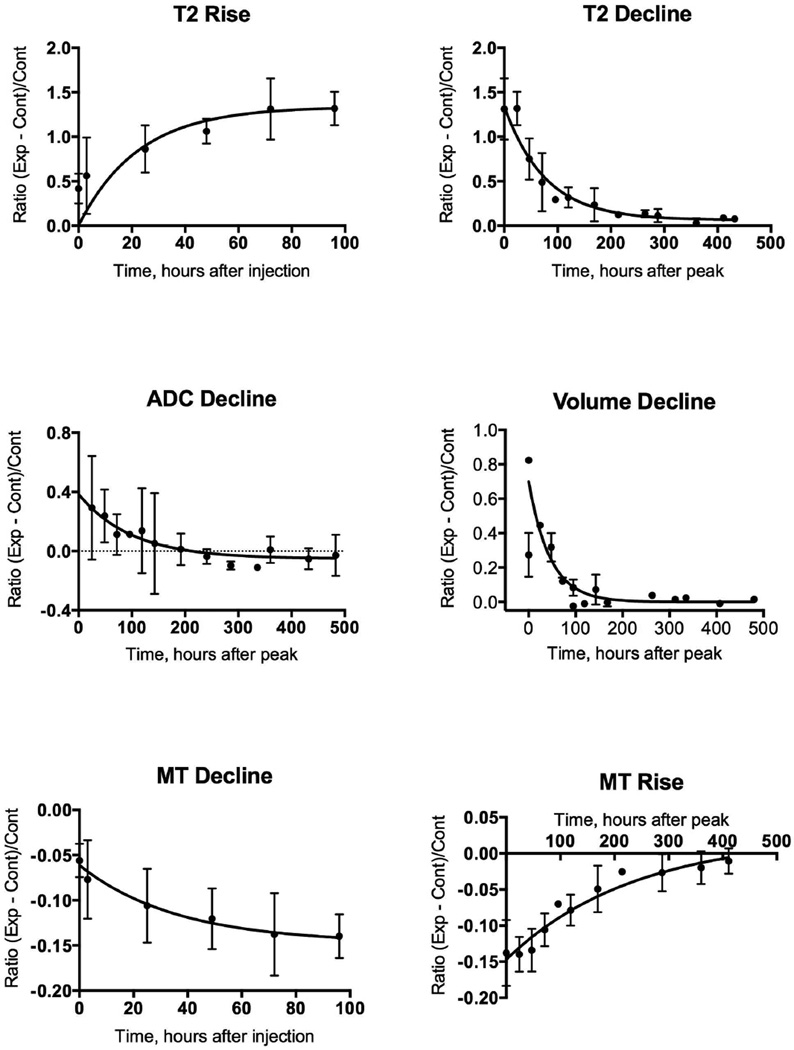

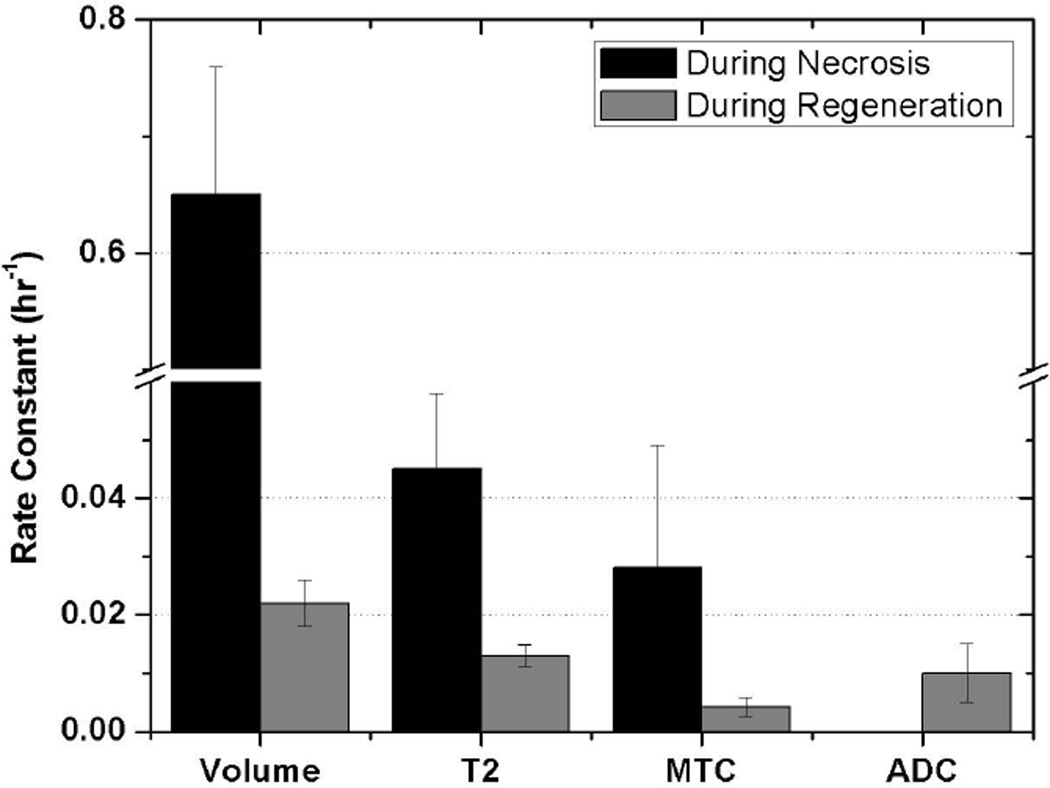

We tested further whether the conclusions about the temporal separation of the different MR parametric images are valid by fitting the data to exponential equations. The times for the maximal changes were estimated by non-linear polynomial fits and these times were used to separate the initial and recovery phases; overlaps of data near the peak were used in the fits. For some of the graphs in Figure 2, there was too much scatter in the data to converge. Therefore we averaged the data from both compartments in each animal and averaged the results of all the animals at common times after toxin injection to give the data presented in Figure 3. The data were grouped into rising and falling phases so that the rates for each could be quantified (Figure 3); the rate constants obtained are summarized in Figure 4. Note only the declines in volume and ADC changes are shown in Figure 3; the ADC data during the initial hours after injection converged but the rate constant, 0.2 hr-1, was not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Data from Figure 2 at common time points were averaged and fitted to an equation: relative intensity at time t = initial intensity + (plateau − initial intensity)•(1−exp(−K*t)). Peaks of parameter intensity were estimated for each graph in Figure 2 and the curves were fitted separately for rising and declining phases. Peak times are evident in Figure 2; peak for volume change was estimated at 20 hours and peak time for ADC was estimated at the time of injection (0 hours).

Figure 4.

Rates of change of MR parameters were analyzed for two periods of both muscle necrosis and regeneration by determining rate constants of muscle volume, T2, MT ratio and ADC. Significantly different are some parameters such as rates of rise between volume and T2, those between volume and MT ratio, and rates of decline among volume, T2 and MT ratio. However, rate of decline of ADC is not significantly different from those of T2 and MT ratio.

These results demonstrate that the changes detected by the several MRI modalities are transient. Recovery was completed within 3 weeks. This result confirms the reversibility summarized in the Introduction and demonstrates a separation in the time courses of the evolution of the MRI changes. These results also show differences in kinetics of the several parametric imaging methods during the phases of damage and of regeneration. These kinetic analyses show that diffusivity of tissue water increases within the first hours after injection of myotoxin and subsequent edema measured by leg volume changes nearly in parallel. This is expected due to the volume of toxin injected (50 µL into each compartment) causing edema. The changes in diffusivity occur early and correspond to the volume changes, followed by changes in T2. The ADC data are particularly noisy so the difference in onset of changes in ADC and volume were not clearly delineated. MT ratio changed the slowest. An important result is that the rate of rise in volume is statistically faster than the rates of rise of T2 and MT ratio; the 95% confidence limits of the volume change do not overlap those of the T2 and MT ratio respectively. The rate of rise of T2 is numerically faster than that of MT ratio but the rates are not different statistically. The data for ADC are too scattered to converge to a statistically significant fit, but, by inspection of data in Figures 2 and 3, the diffusion appears to change more rapidly than the other MR parameters (T2 and MT ratio). After damage is maximal and regeneration begins, volume, T2, ADC and MT modalities change towards control values with MT ratio having a slower recovery time course than the others.

Pathology

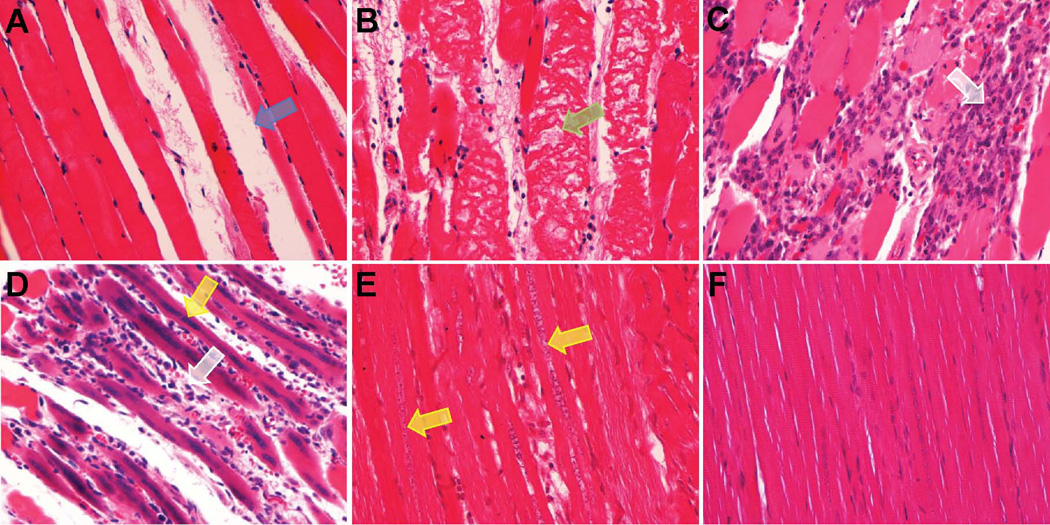

Histological analyses showed changes in structural and cellular features of the leg that matched the progression of MR images. Analysis of histological sections showed progressive muscle damage, necrosis and regeneration during three weeks from injection of the toxin. Figure 5 displays representative images of H&E staining muscle tissues at different time points after myotoxin injection to illustrate these findings. Muscle edema appeared a few hours after injection of BaCl2 in some sections without evidence of altered sarcomeric structure. Within 24 hours of injection, there was moderate edema (see Figure 5A) and myofiber degeneration and necrosis as shown in Figure 5B. At day 3 after toxin injection extensive damage is visible with advanced myofiber necrosis and numerous interstitial macrophages (see Figure 5C). On day 5 after toxin injection focal lymphohistiocytic inflammation was evident within the interstitium and surrounding degenerative myofibers with some regenerating myofibers (see Figure 5D). On day 8, there is mild interstitial inflammatory infiltration with multifocal myofiber degeneration, necrosis, and many regenerating myofibers. Regeneration was evidenced by small diameter myofibers with faintly basophilic cytoplasm and an internal chain of nuclei evidenced by the H&E image shown in Figure 5E. On day 20, the muscle cell and tissue structure returned mostly to normal as displayed in Figure 5F. Masson’s trichrome stain failed to show regions of fibrosis in any slides during the time course of the experiments. Thus the time course of changes in the microscopic structure of the leg musculature matched the time course of changes in the MR images, with maximal changes occurring at 3 to 5 days following injection of myotoxin.

Figure 5.

Representative images of H&E stained muscle tissues at different time points after injections of BaCl2: immediately after injection at day 0 (A), day 1 (B), day 3 (C), day 5 (D), day 8 (E) and day 20 (F) (magnification, ×40). Muscle degeneration and regeneration processes are noticed with edema (blue arrow), myofiber fragmentation (green arrow), macrophages (white arrow) and regenerating myofibers (yellow arrows).

DISCUSSION

The literature on MR imaging of muscle damage and regeneration cited in the Introduction demonstrates the feasibility of detecting muscle damage by MRI. The MRI modalities used in this study are time-sensitive to the evolution of necrosis to recovery and appear to have different kinetics. Our results show it is possible to discern the kinetics of damage and subsequent regeneration by several MRI modalities. The design of our experiments was to explore the time course of four conventional imaging methods, originally as a pilot project, using a chemical method of damage known to be reversible. Because the several MRI modalities have discernibly different kinetics, our results mean it may be possible to correlate specific MRI parameters and imaging protocols with identifiable tissue and cellular changes during the processes of damage and regeneration. Thus further work to develop kinetic approaches to imaging muscle damage and regeneration by as many MRI parameters is practical and goal of making correlations of MRI characteristics with known cellular and molecular events is feasible.

Our work advances the capability of MR to assess muscle damage and regeneration in a number of ways. For example, diffusion imaging is sensitive to the earliest change after myotoxin injection, namely initial muscle edema without cellular damage being visible by light microscopy. MRI modalities have separate time courses in diffusion imaging occurring before T2 changes. T2 changes are maximal slightly before the maximum in MT ratio changes. Further, we obtained our results without optimizing the sequences (for example to be more time efficient or to improve the signal to noise and image resolution) which shows further work to evaluate the suggested correlations will be productive especially if complemented by measurements of mechanical function and specific labeling with molecular markers in histological analyses.

On the basis of the differential time courses of the several MRI modalities and the pathology identified in the histological sections, we can make several tentative correlations between MRI results and the underlying cellular and tissue pathology. Diffusion weighted imaging monitors changes in muscle microstructural integrity and edema by measuring apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values. Magnetization transfer ratio identifies myofibrillar destruction and muscle regeneration. ADC, muscle volume and edema correlate. These are the earliest changes seen after myotoxin injection. Changes in intensity of T2 maps correlated with muscle damage and onset of inflammatory cell infiltration. MT ratio changes may be the least specific because they appear to reflect muscle necrosis, myofibrillar degeneration, inflammation and continued macrophage invasion and onset of regeneration. Elevated MT ratios persist during regeneration, a finding that suggests MT ratio imaging may be the least specific of the MRI modalities studied. Thus proton MRI gives good anatomical images of muscle and the several parametric mapping methods establish the basis for distinguishing different tissue changes causing the changes in MR parameters.

For T1 and T2 imaging, we used a single spin echo sequence rather than multi spin echo sequence to avoid imperfect radiofrequency pulses and unusually high signal in later echoes due to T1 relaxation of stimulated echoes (20,21). Magnetization transfer contrast (MTC) imaging provides a quantitative parameter measuring the exchanges of the proton moieties in water with those in proteins and macromolecules (16,25). This MR modality tested whether the damaged and denatured intracellular macromolecules have greater amounts and rates of exchange with water protons. These changes can be detected and quantified by measuring magnetization transfer (MT) suppression ratios or MT ratios.

The scope of this study was designed narrowly, so it has a number of limitations. First, we used only one method of inducing muscle damage, namely the toxic chemical BaCl2. We expect that the other chemical toxins, cardiotoxin and notexin, would give similar effects because these three toxins primarily induce muscle cell necrosis. In contrast mechanical trauma and crush injury damages muscle cells and their basement membranes, nerves and blood vessels and are known to cause fibrosis. We saw no histological evidence of fatty infiltrates or fibrosis that is highly relevant to human muscle injury (26). Another limitation is we did not optimize the MR sequences with each other so as to identify maximal responses that would allow more detailed quantitative comparisons and enhance spatial resolution with better signal to noise. Even so the different MR modalities have distinguishable kinetics. Our histological studies were qualitative and used only standard staining methods. Reconstruction of the entire damaged region with systematic study would make possible analyses of the uniformity or heterogeneity of the muscle’s response to the chemical injury. Finally, no assessment of muscle mechanical function was made and it is clear from treatment of sports injuries to muscle that this information is very valuable clinically (26).

Improvements to make additional progress would include higher time resolution during the first week of changes. Processes during damage, necrosis and inflammation occur very rapidly, having maximal changes in 3 days after toxin injection. Our design of daily imaging was just sufficient to detect differences in the time course of T2w and MTC. Better temporal resolution might require imaging at 6 to 12 hour intervals during these rapid changes in mice. Alternatively use of a larger animal could be advantageous because the changes would occur more slowly, although Mattila (15) found similarly rapid changes in a rat model. Improvements in signal to noise and optimization of image resolution were mentioned already and these would localize the damage and regeneration better. The effects of injecting 50 µL of BaCl2 toxin spread widely in both compartments of the leg. The damaged region of the leg at peak had five or more times greater volume than the volume injected. Other toxins and smaller volumes injected may localize the damage to smaller volumes in the limb. Increased localization could facilitate comparison of MRI with histology especially with full analyses of the entire affected volume. We did not attempt imaging with other MR nuclei, such as 23Na that would reflect both edema (a smaller effect due to expansion of extracellular space) and cell damage (a larger effect due to increase in Na+ into the volume of damaged cells). Likewise volume selective 31P spectroscopy of high-energy phosphate metabolites would further characterize the time course of damage and regeneration. Finally imaging in higher field magnets would improve signal to noise and give higher spatial resolution than achieved here.

In conclusion, multi-parametric MRI of T1, T2, MT and diffusion effects has feasibility for identifying tissue and cellular necrosis and regeneration in skeletal muscles. The kinetics of change in the MRI modalities can be distinguished during muscle damage and regeneration and provide a basis for specific MRI methods to distinguish the underlying tissue and cellular processes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Sue Knoblaugh at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center for her review of some histology slides.

Grant Support: NIH grants R01AR041928 and R21EB008166

REFERENCES

- 1.Mercuri E, Jungbluth H, Muntoni F. Muscle imaging in clinical practice: diagnostic value of muscle magnetic resonance imaging in inherited neuromuscular disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18(5):526–537. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000183947.01362.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gadian DG. Nuclear magnetic resonance and its applications to living systems. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumura K, Nakano I, Fukuda N, Ikehira H, Tateno Y, Aoki Y. Duchenne muscular dystrophy carriers. Proton spin-lattice relaxation times of skeletal muscles on magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroradiology. 1989;31(5):373–376. doi: 10.1007/BF00343858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumura K, Nakano I, Fukuda N, Ikehira H, Tateno Y, Aoki Y. Proton spin-lattice relaxation time of Duchenne dystrophy skeletal muscle by magnetic resonance imaging. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11(2):97–102. doi: 10.1002/mus.880110202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, Majumdar S, Genant HK, et al. Quantitative MR relaxometry study of muscle composition and function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;4(1):59–64. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880040113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gong QY, Phoenix J, Kemp GJ, et al. Estimation of body composition in muscular dystrophy by MRI and stereology. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12(3):467–475. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200009)12:3<467::aid-jmri13>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wishnia A, Alameddine H, Tardif de Gery S, Leroy-Willig A. Use of magnetic resonance imaging for noninvasive characterization and follow-up of an experimental injury to normal mouse muscles. Neuromuscul Disord. 2001;11(1):50–55. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(00)00164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Nierop BJ, Stekelenburg A, Loerakker S, et al. Diffusion of water in skeletal muscle tissue is not influenced by compression in a rat model of deep tissue injury. J Biomech. 2010;43(3):570–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walter G, Cordier L, Bloy D, Sweeney HL. Noninvasive monitoring of gene correction in dystrophic muscle. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(6):1369–1376. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson BM, Faulkner JA. The regeneration of skeletal muscle fibers following injury: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1983;15(3):187–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kherif S, Lafuma C, Dehaupas M, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in regenerating skeletal muscle: a study in experimentally injured and mdx muscles. Dev Biol. 1999;205(1):158–170. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heemskerk AM, Drost MR, van Bochove GS, van Oosterhout MF, Nicolay K, Strijkers GJ. DTI-based assessment of ischemia-reperfusion in mouse skeletal muscle. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(2):272–281. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boesch C, Kreis R. Dipolar coupling and ordering effects observed in magnetic resonance spectra of skeletal muscle. NMR Biomed. 2001;14(2):140–148. doi: 10.1002/nbm.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leibfritz D, Dreher W. Magnetization transfer MRS. NMR Biomed. 2001;14(2):65–76. doi: 10.1002/nbm.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattila KT, Lukka R, Hurme T, Komu M, Alanen A, Kalimo H. Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetization transfer in experimental myonecrosis in the rat. Magn Reson Med. 1995;33(2):185–192. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henkelman RM, Stanisz GJ, Graham SJ. Magnetization transfer in MRI: a review. NMR Biomed. 2001;14(2):57–64. doi: 10.1002/nbm.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heemskerk AM, Strijkers GJ, Drost MR, van Bochove GS, Nicolay K. Skeletal muscle degeneration and regeneration after femoral artery ligation in mice: monitoring with diffusion MR imaging. Radiology. 2007;243(2):413–421. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2432060491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDaniel JD, Ulmer JL, Prost RW, et al. Magnetization transfer imaging of skeletal muscle in autosomal recessive limb girdle muscular dystrophy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23(4):609–614. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199907000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caldwell CJ, Mattey DL, Weller RO. Role of the basement membrane in the regeneration of skeletal muscle. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1990;16(3):225–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1990.tb01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Constable RT, Anderson AW, Zhong J, Gore JC. Factors influencing contrast in fast spin-echo MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1992;10(4):497–511. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(92)90001-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.St Pierre TG, Clark PR, Chua-Anusorn W. Single spin-echo proton transverse relaxometry of iron-loaded liver. NMR Biomed. 2004;17(7):446–458. doi: 10.1002/nbm.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Aubin ML, Vignaud J, Laval-Jeantet M. Separation of diffusion and perfusion in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;168(2):497–505. doi: 10.1148/radiology.168.2.3393671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, et al. Contribution of intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) imaging to neuroradiology. J Neuroradiol. 1987;14(4):295–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stejskal EO, Tanner JE. Spin diffusion measurements: spin echoes in the presence of a time-dependent field gradient. J Chem Phys. 1965;42:288–292. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff SD, Chesnick S, Frank JA, Lim KO, Balaban RS. Magnetization transfer contrast: MR imaging of the knee. Radiology. 1991;179(3):623–628. doi: 10.1148/radiology.179.3.2027963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winkler T, von Roth P, Matziolis G, et al. Time course of skeletal muscle regeneration after severe trauma. Acta orthopaedica. 2011;82(1):102–111. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.539498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]