Abstract

Aggressive cancers and embryonic stem (ES) cells share a common gene expression signature. Identifying the key factors/pathway(s) within this ES signature responsible for the aggressiveness of cancers can lead to a potential cure. In this study, we find that SALL4, a gene involved in the maintenance of ES cell self-renewal, is aberrantly expressed in 47.7% of primary human endometrial cancer samples. It is not expressed in normal or hyperplastic endometrial. More importantly, SALL4 expression is positively correlated with worse patient survival and aggressive features such as metastasis in endometrial carcinoma. Further functional studies have shown that loss of SALL4 inhibits endometrial cancer cell growth in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo, as a result of inhibition of cell proliferation and increased apoptosis. In addition, down-regulation of SALL4 significantly impedes the migration and invasion properties of endometrial cancer cells in vitro and their metastatic potential in vivo. Furthermore, manipulation of SALL4 expression can affect drug sensitivity of endometrial cancer cells to carboplatin. Moreover, we show that SALL4 specifically binds to the c-Myc promoter region in endometrial cancer cells. While down-regulation of SALL4 leads to a decreased expression of c-Myc at both protein and mRNA levels, ectopic SALL4 overexpression causes increased c-Myc protein and mRNA expression, indicating that c-Myc is one of the SALL4 downstream targets in endometrial tumorigenesis. In summary, we are the first to demonstrate that SALL4 plays functional role(s) in metastasis and drug resistance in aggressive endometrial cancer. As a consequence of its functional roles in cancer cell and absence in normal tissue, SALL4 is a potential novel therapeutic target for the high risk endometrial cancer patient population.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, SALL4, metastasis, chemoresistance

Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the world. According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), there are 8,010 deaths from endometrial cancer in the United States in 2012. While most patients (80%) can be surgically cured with a hysterectomy, the remaining 20% patients who are diagnosed with advanced or recurrent disease have far worse survival rates and limited adjuvant treatment options 1, 2. Discovery of novel target(s)/pathway(s) is needed for better understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment development for this disease. Recent studies have shown that aggressive tumor cells share a common gene expression signature with embryonic stem (ES) cells 3, 4. In these studies, SALL4 has been identified as one of the top-ranked genes enriched in high-grade cancers. As a transcription factor, SALL4 is known for its essential role in early embryonic development, and Sall4 null mice die shortly after implantation 5, 6. Similar to OCT4, SOX2 and NANOG, SALL4 is essential to maintain ES cells in a self-renewal and undifferentiated state. By using a transgenic murine model, we previously reported that SALL4 can function as an oncogene in leukemogenesis 7. Thereafter, its aberrant expression in germ cell tumors and other solid tumors has been reported by various groups 8–10. However, in-depth studies on the functional role(s) of SALL4 in tumorigenesis of uterine tumors are still lacking.

In this study, by screening SALL4 expression in a cohort of endometrial cancer samples, we find that SALL4 is aberrantly expressed in endometrial cancer patient samples when compared to normal controls. More importantly, high SALL4 expression is significantly correlated with worse patient survival and metastasis capacity. Using human endometrial cancer cell lines, we have further conducted extensive investigations on the biological role of SALL4 in endometrial carcinogenesis. Both our in vitro and in vivo data strongly suggest that SALL4 expression is essential in endometrial cancer survival and progression, which is achieved by promoting tumor metastasis and chemoresistance. This mechanism of SALL4 in endometrial cancer is mediated at least in part through activation of c-Myc. Taken together our studies hold potential promise on targeting SALL4 as a novel therapeutic option for endometrial cancer patients, especially those with advanced or recurrent disease.

Results

SALL4 is aberrantly expressed in endometrial carcinoma, and significantly correlated with poor survival

To examine SALL4 expression in endometrial cancer, we constructed and screened a panel of tissue microarrays consisting of 113 endometrial cancer samples. Twenty one normal endometria and five hyperplastic samples were used as controls. Among the 113 endometrial cancer cases, 47.7% were positive for SALL4 expression, albeit at variable expression levels. In contrast, SALL4 expression was not detected in hyperplasic and normal endometrial tissues. The data are summarized in Table 1 and Table S1, and representative images are shown in Figure 1a and S1. In addition, we also evaluated SALL4 mRNA expression in endometrial cancers. Using snap-frozen patient samples, SALL4 mRNA expression was validated in endometrial carcinoma samples using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Since we have previously identified that human SALL4 has two isoforms (SALL4A and SALL4B) 7, isoform-specific primers and Taqman probes were used for qRT-PCR. By qRT-PCR, we established that both isoforms were elevated in a subgroup of primary endometrial cancers compared to normal (Figure S1).

Table 1.

Correlation of SALL4 histoscore with clinicopathological characteristics of the patients with endometrial cancer.

| Clinical and pathological features | Case (n)a | SALL4 (histoscore) positive (%)b |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| <50 | 16 | 25% |

| ≥50 | 97 | 50% |

| Histology | ||

| Endometrioid | 49% | |

| Grade 1 | 57 | 54% |

| Grade 2 | 35 | 42% |

| Grade 3 | 18 | 72% |

| Clear cell | 3 | 0% |

| FIGO Stage | ||

| Stage 1 | 81 | 45% |

| Stage 2 | 13 | 76% |

| Stage 3 | 16 | 43% |

| Stage 4 | 3 | 33% |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||

| Present | 17 | 64% |

| Absent | 83 | 48% |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||

| No | 106 | 45% |

| Yes | 7 | 71% |

Total number of cases=113;

SALL4 positive indicates more than 5% of tumor cells staining positive.

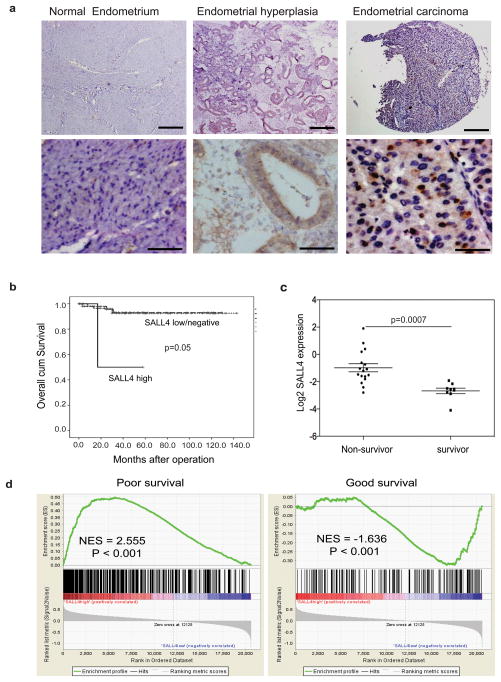

Figure 1. SALL4 expression is associated with poor survival and metastasis in endometrial cancer patients.

(a) Representative IHC images show positive SALL4 expression in endometrial cancer and absence of SALL4 in normal endometria and hyperplasia. Scale bars = 500μm (upper panels) and 50μm (lower panel). (b) Clinicopathological analysis demonstrates SALL4 expression is significantly correlated with worse survival of EC patients (p =0.05). SALL4 low/negative group includes IHC 0 and 1+, and SALL4 high group includes IHC 2+ or above. (c) Microarray analysis confirms that SALL4 expression was significantly higher in non-survivor compared to survivor of endometrial cancer. (d) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) reveals that in high SALL4-expressing endometrial carcinoma, there is an enrichment of gene sets upregulated in cancers with poor survival (left panel, p<0.001); On the contrary, gene sets that are enriched in cancers with good survival are enriched in SALL4-negative endometrial carcinoma (right panel, p<0.001).

To examine if the upregulation of SALL4 has any clinical significance in endometrial carcinoma, we carried out clinicopathological analysis to see if SALL4 expression predicts poor prognosis. We retrieved clinicopathological and demographic data of 113 endometrial carcinoma cases (Table 1 and S2). We found that SALL4 expression was significantly correlated with poor survival of EC patients (P = 0.05) (Figure 1b).

We next chose to compare our observation with existing published expression database on endometrial cancer. Levan et al. have reported a gene signature that can predict poor prognosis in endometrial carcinoma 11. We extracted the gene expression profiles and re-analyzed the data in order to examine if SALL4 was differentially expressed between survivor and non-survivor groups. We found that SALL4 expression was significantly higher in the non-survivor compared to the survivor group (Figure 1c). Furthermore, we carried out Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to investigate if gene sets that have prognostic values are enriched in SALL4-expressing endometrial carcinomas from the same database. Indeed, in SALL4-expressing endometrial carcinoma, we observed enrichment of gene sets upregulated in cancers with poor survival (P < 0.001), metastasis (P < 0.001), advanced tumor stage (P < 0.001), and proliferation (P < 0.001). On the other hand, gene sets that are enriched in cancers with good survival (P < 0.001) and downregulated in cancers of advanced stage (P < 0.001), proliferation (P = 0.006) and metastasis (P = 0.047) are enriched in SALL4-negative endometrial carcinomas (Figure 1d and Figure S2).

In summary, these results support that SALL4 expression is significantly correlated with poor survival of endometrial cancer patients.

Silencing of SALL4 inhibits cell growth in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo as a result of decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis

To assess the biological functional role of SALL4 in endometrial cancer, we first evaluated SALL4 expression in a panel of six endometrial cancer cell lines using qRT-PCR to select for appropriate models for our functional studies (Figure S3). Three cell lines, AN3CA, HEC-1A and Ishikawa were selected for subsequent studies based on their endogenous SALL4 expression of high, moderate, or undetectable levels, which best represented the differential SALL4 expression levels encountered in primary human endometrial cancer tissues. To suppress SALL4 expression in endometrial cancer cells, two short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) specifically targeting both SALL4A and SALL4B isoforms, designated as SALL4-sh1 and SALL4-sh2, were chosen and optimized from 5 constructs. AN3CA and HEC-1A cells were infected with lentivirus expressing shRNAs. On day 4 after infection, loss of SALL4 induced substantial cell death in both AN3CA and HEC-1A cells. The changes in cell morphology and apoptotic phenotypes were visible by light microscopy (Figure 2a). Knockdown efficiency of the two shRNAs was verified by Western blot and qRT-PCR (Figure 2b and c). Both shRNAs could down-regulate SALL4A and SALL4B efficiently in AN3CA and HEC-1A cells.

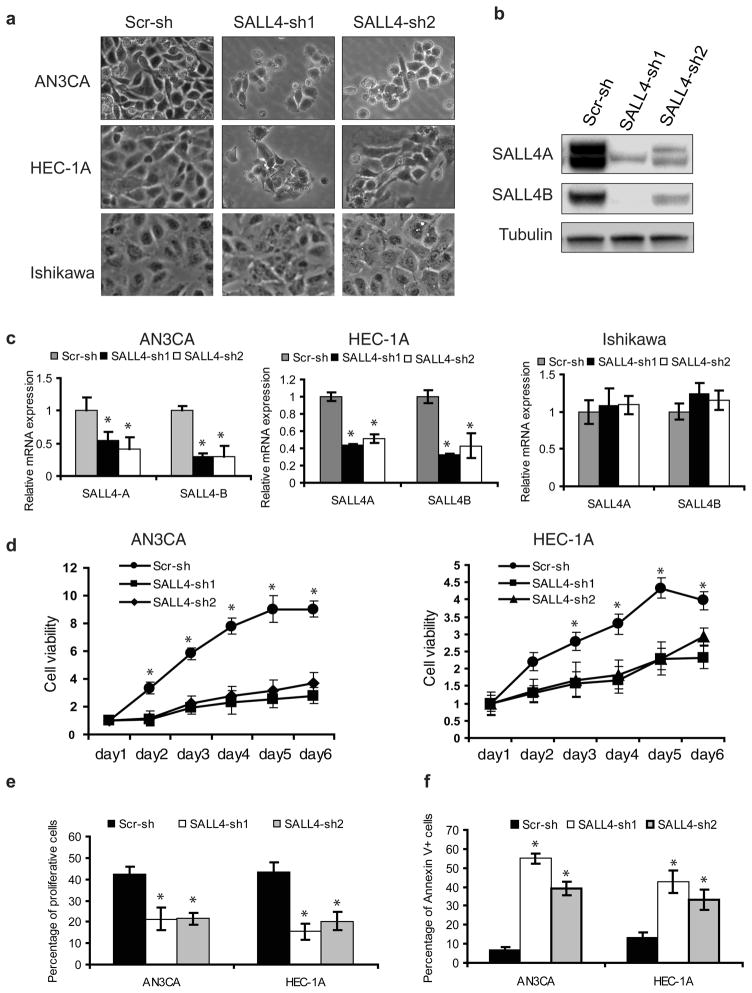

Figure 2. SALL4 depletion decreases cell viability by inhibiting proliferation and triggering cell apoptosis in vitro.

(a) Phase-contrast photomicrographs show decreased viable cells by morphology after SALL4 knockdown. (b) Western blot demonstrates downregulation of SALL4 expression in AN3CA cells as a result of lentiviral-mediated RNA interference. (c) Downregulation of SALL4 expression by shRNA targeting can lead to decreased SALL4 expression in AN3CA and HEC-1A cells, but not in Ishikawa cells, evaluated by qRT-PCR. (d) Down-regulation of SALL4 leads to decreased cell viability. Cells expressing SALL4 shRNAs or scrambled control shRNAs were plated in 96-well plates (2000 cells per well) and cell viability assayed at various time points using the MTS assay. (e) Down-regulation of SALL4 leads to decreased cell proliferation. Cells expressing SALL4 shRNAs (SALL4-sh1 and SALL4 sh2) or scrambled shRNAs (Scr-sh) were pulse-labeled with BrdU for 1hr, followed by analysis of DNA replication with anti-BrdU antibody and flow cytometry analysis to measure proliferating cells. (f) Down-regulation of SALL4 leads to increased apoptosis. Cells expressing SALL4 shRNAs or scrambled shRNAs were collected, stained with PI and Annexin V, and processed for analysis by flow cytometry to measure the apoptotic cells. Error bars indicate standard error of three replicates (n =3) (*p<0.05, Student’s t test).

To elucidate the role of SALL4 in endometrial cancer cell survival, the viability of lentiviral-infected AN3CA and HEC1-A cells was first examined by MTS assay over a period of time. The growth rate of SALL4-knockdown cells was significantly decreased compared to those of scrambled shRNA-treated control cells (Figure 2d). In contrast, no significant effect was observed upon SALL4 knockdown in Ishikawa cells, which had undetectable SALL4 expression endogenously (Figure S4). To further verify that the effects of shRNAs are specific, we prepared SALL4A and SALL4B overexpression constructs that carried triple-point mutation within the 21-bp sequence targeted by SALL4-sh1. These mutations did not lead to an amino acid sequence change of SALL4 protein but rendered the overexpression constructs insensitive to inhibition by SALL4-sh1, and therefore could be used as rescue mutants to test the specificity of the shRNA. After co-infection of AN3CA cells with SALL4-sh1 and rescue mutant SALL4A or SALL4B lentivirus, we observed that mutant SALL4A alone or SALL4B alone was able to partially rescue SALL4 shRNA induced phenotype (Figure S5).

The decrease in cell growth could be due to impaired proliferation and/or increased cell death. To determine the effect of SALL4 knockdown on cell proliferation, we measured BrdU incorporation in vitro by flow cytometry. SALL4 knockdown significantly decreased the proportions of BrdU-positive proliferating endometrial cancer cells (Figure 2e). We next assessed the effect of SALL4 depletion on the apoptotic activity of the endometrial cancer cells using AnnexinV staining. The percentages of Annexin V-positive cells were much higher in SALL4 knockdown groups than the scrambled control groups (Figure 2f). Collectively, these data suggest that loss of SALL4 inhibits cell proliferation and triggers cell apoptosis in vitro.

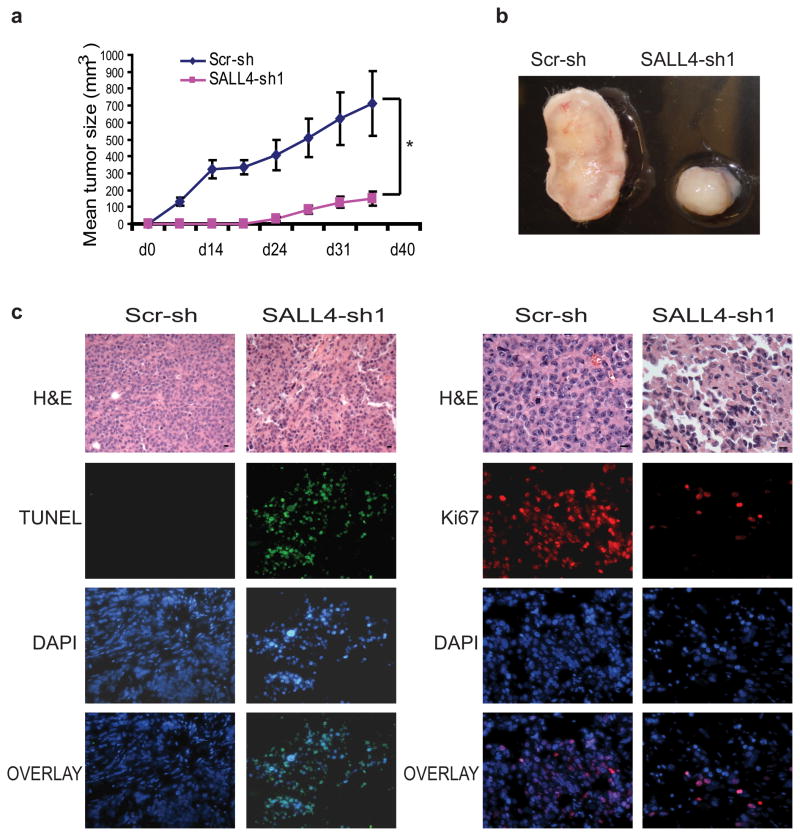

The oncogenic role of SALL4 in endometrial cancer was further confirmed by using xenograft mouse models. First, a subcutaneous xenograft mouse model was developed to assess the tumor growth rate in vivo. Two million AN3CA cells treated with either scrambled control or SALL4 shRNA-expressing lentiviruses were injected subcutaneously into the right flank region of NOD/SCID mice and monitored for tumor development. As shown in Figure 3a and b, tumor growth induced by the SALL4 knockdown group was dramatically slower than that induced by scrambled shRNA-treated cells. The excised tumors were then subjected to routine histology processing and immunostaining analysis. Cellular proliferation in tumor tissues was assessed by immunostaining with anti-Ki-67 antibody (Figure 3c, right panel). Decreased Ki-67 staining was observed in the small tumors induced by SALL4 knockdown cells compared to the controls, suggesting that loss of SALL4 could significantly inhibit cell proliferation. On the contrary, subcutaneous tumors induced by SALL4 knockdown cells showed a marked increase in the number of apoptotic cells as detected by TUNEL analysis (Figure 3c, left panel).

Figure 3. SALL4 depletion inhibits tumorigenecitiy of AN3CA cells in vivo.

(a) Graph shows tumor volume (mm3) measured at various time points after transplantation (n = 5). Error bars indicate standard error from five mice (*p<0.05, Student’s t test). Tumor volume (mm3) was calculated by the following formula: length×width× height/2. (b) Representative gross picture of tumors derived from subcutaneous injection of AN3CA cells expressing SALL4-sh1 or scrambled shRNA (Scr-sh). (c) AN3CA tumor sections treated with SALL4-sh1 shRNA have reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis as measured by IHC Ki-67 and TUNEL staining, respectively.

Despite the fact that the subcutaneous xenograft murine model is suitable for monitoring tumor growth locally, this model has limitations in mimicking human endometrial cancer disease progression. Therefore, we also attempted an intra-peritoneal xenograft model to assay for the effect of SALL4 down-regulation on the tumorigenicity of AN3CA cells. Ten million AN3CA cells treated with either scrambled control or SALL4 shRNA-expressing lentiviruses were injected into the peritoneal cavity of NOD/SCID mice and the recipients mice were monitored for tumor development and overall health status. While the scrambled control-treated NOD/SCID recipient mice died of disseminated tumor within 2 months of tumor cell injection, the SALL4 shRNA-treated NOD/SCID recipient mice were still alive at the end of study. A statistically significant difference in survival was observed between the two groups of mice (Figure S6).

Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate that silencing SALL4 inhibits endometrial cancer cell growth in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo by inhibiting proliferation and triggering apoptosis.

Down-regulation of SALL4 decreases the invasiveness of endometrial cancer in vitro and blocks its metastatic potential in vivo

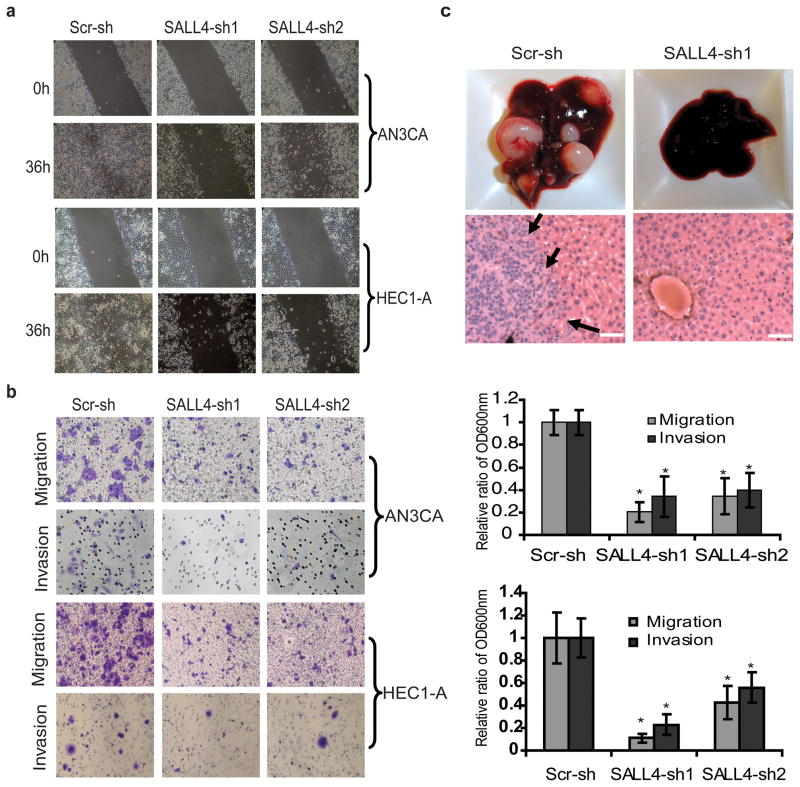

Metastasis is a central problem in cancer therapeutics. Since our analysis showed a positive correlation between SALL4 expression and endometrial cancer metastasis, we next aimed to assess whether loss of SALL4 could affect tumor invasiveness. In a wound-healing assay, a much slower wound closure rate was observed in the SALL4 knockdown AN3CA and HEC-1A cells as compared to the scrambled shRNA-treated cells (Figure 4a). In transwell migration and invasion assays, significantly reduced migration and invasion were also observed in AN3CA and HEC-1A cells upon SALL4 knockdown (Figure 4b). We then asked whether loss of SALL4 could influence cell migration and metastasis formation in vivo. We compared the invasive potential of AN3CA, HEC-1A and Ishikawa cell lines in vitro and detected a strong association between SALL4 expression and invasive capacity, with Ishikawa showed the least migration/invasion ability.

Figure 4. SALL4 depletion inhibits endometrial cancer cells migration, invasion and metastasis.

(a) Phase contrast microscopy images demonstrate impaired AN3CA and HEC-1A cells wound closure rate as a result of loss of SALL4. (b) Left panel shows that representative transwell cell migration and matrigel cell invasion images. Right panel shows that migration and invasion capacities were quantified after the cells stained with crystal violet solution. Data are presented as OD600nm. Error bars indicate standard error of three replicates (n =3) (*p<0.05). (c) Liver tissues from mice retro-orbitally injected with SALL4-knockdown or scrambled control shRNA-treated AN3CA cells. Upper panel, gross liver tissue pictures; lower panel, representative H&E staining on liver tissues. Arrows indicate metastatic tumor region. Scale bar represents 50μm (* p<0.05).

We next explored the role of SALL4 in endometrial cancer metastasis by using another xenotransplant model. The most invasive cell line with high endogenous SALL4 expression, AN3CA, was chosen for the in vivo metastasis assay. SALL4-knockdown or scrambled shRNA-treated AN3CA cells were injected into NOD/SCID mice through the retro-orbital route, representing an intra-venous (i.v.) xenotransplant model. Metastasis of the tumor in all organs was evaluated 6 weeks later when scrambled shRNA-treated recipient mice became morbid. Five out of six scrambled shRNA-treated AN3CA recipients had markedly enlarged tumor-bearing livers (Figure 4c, left upper panel), with tumor morphology recapitulating that of the tumors found in patients with poorly differentiated invasive endometrial carcinoma (Figure 4c, left lower panel and Figure S7). In contrast, all the SALL4 shRNA-treated AN3CA recipients (n=9) had no detectable tumors macroscopically or microscopically by routine H&E examination in any of the organs we evaluated, including liver, kidney (Figure S7), lung and spleen. Only by staining for GFP, which was used to mark the shRNA infected tumor cells, we were able to identify a few microscopic clusters of GFP positive cells in the tissues of SALL4-shRNA treated recipient mice (Figure S8). This is in contrast to large GFP positive tumor nodules in tissue organs observed in scrambled shRNA-treated recipient mice (Figure S8). These data suggest that SALL4 is essential to maintain the invasive state of endometrial cancer cells.

Manipulation of SALL4 expression affects the sensitivity of endometrial cancer cells to carboplatin treatment

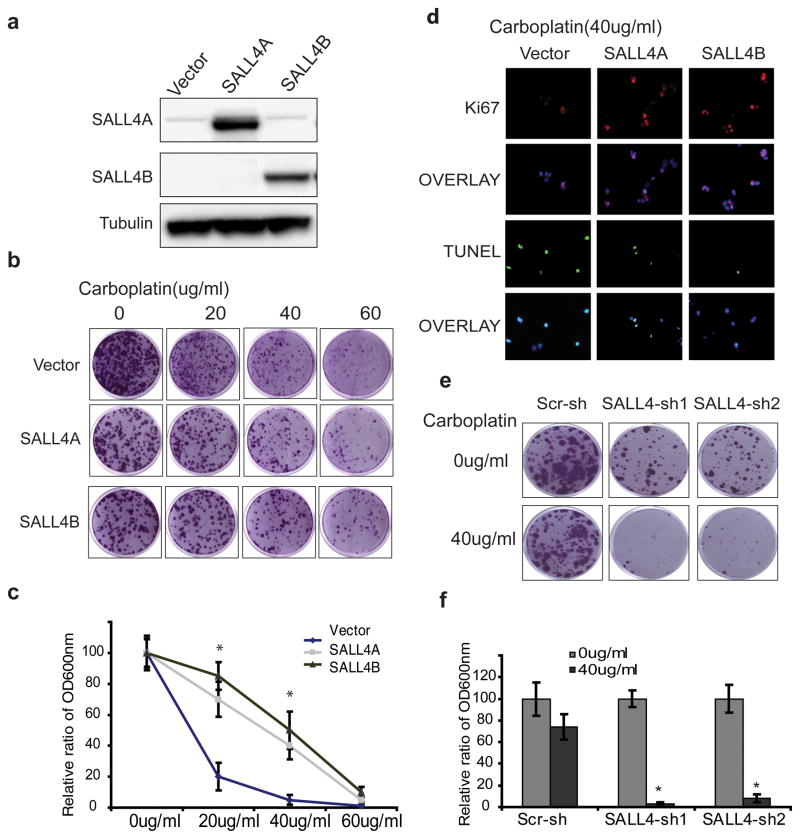

Drug resistance is another important problem in endometrial cancer patients with advanced stages. We next asked whether SALL4 expression could affect the sensitivity of endometrial cancer cells to carboplatin treatment. Clonogenic assay and MTS assay revealed that overexpression of SALL4 in carboplatin-sensitive Ishikawa cells could promote carboplatin-resistance in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5a, b, c and figure S9). Furthermore, we observed that both SALL4A and SALL4B transfected Ishikawa showed increased proliferation after carboplatin treatment compared to empty vector control as demonstrated by Ki-67 staining (Figure 5d). In addition, SALL4 overexpression could significantly protect cells from apoptosis induced by carboplatin treatment, assayed by TUNEL staining (Figure 5d). On the contrary, in carboplatin resistant HEC-1A cells, knocking-down SALL4 significantly restored the sensitivity of these cells to carboplatin treatment (Figure 5e and f).

Figure 5. Change of SALL4 expression leads to alterations in drug sensitivity of endometrial cancer cells to Carboplatin.

(a) Western blot demonstrates ectopic overexpression of SALL4 in Ishikawa cells. (b) Clonogenic assays on Ishikawa cells overexpressing SALL4A or SALL4B treated with indicated carboplatin concentrations; images show colonies stained with crystal violet solution. (c) Quantification of the relative colony formation in empty vector control group versus SALL4 overexpression groups following drug treatments (* p<0.05). (d) Overexpression of SALL4 renders Ishikawa more resistant to carboplatin treatment (40μg/ml carboplatin treated for 72hrs) by promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis, as measured by Ki-67 and TUNEL staining. (e) Knockdown of SALL4 sensitized carboplatin-resistant cell line HEC-1A to carboplatin treatment, as measured by decreased colony formation. (f) Quantification of relative colony formation in control versus SALL4 knockdown HEC-1A cells with and without 40μg/ml carboplatin treatment (* p<0.05).

In summary, our data suggest that in endometrial cancer, upregulation of SALL4 expression can contribute to chemotherapy resistance.

SALL4 directly regulates c-Myc transcriptional activity in endometrial cancer cells

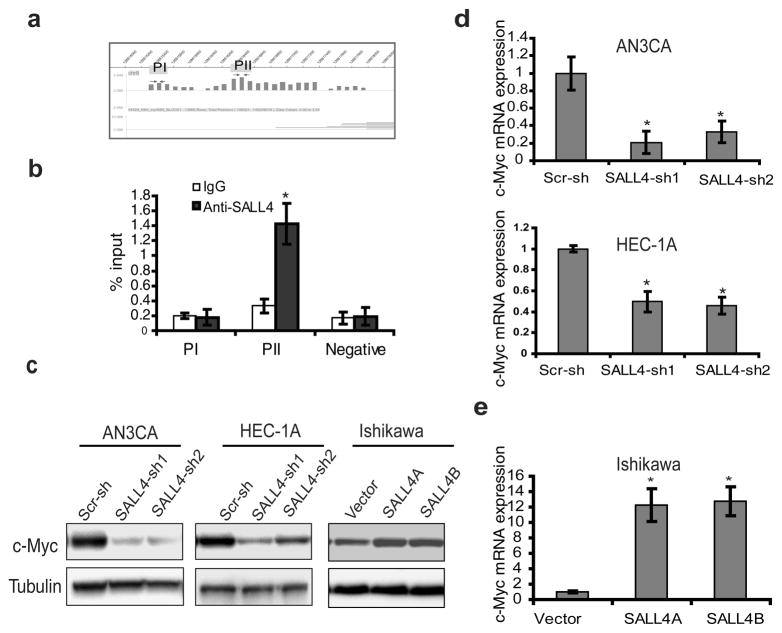

To explore the mechanism of SALL4 in endometrial cancer, we focused on its potential downstream target gene(s) known to be involved in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. We have previously performed a genome-wide analysis of SALL4 target genes in myeloid leukemic NB4 cells as well as murine ES cells using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by microarray on the promoter regions (ChIP-chip) approach 12, 13. Re-analyzing these ChIP-chip data sets, we found that SALL4 could bind to the c-Myc promoter region in these cells (Figure 6a). It is possible that SALL4 regulates c-Myc in endometrial cancer as well. To test this hypothesis, we verified the ChIP-chip result quantitatively using a regular ChIP coupled with qPCR approach. We demonstrated that SALL4 indeed could bind to the promoter region of c-Myc in AN3CA cells (Figure 6b). To examine the regulatory effect of SALL4 on c-Myc expression, we performed western blot and qRT-PCR analysis after SALL4 knockdown in AN3CA and HEC-1A cells. SALL4 silencing in these two cell lines significantly decreased the protein and mRNA expression of c-Myc compared to scrambled control (Figure 6c and d). A parallel ectopic SALL4 overexpression experiment was carried out in Ishikawa cells, which have negligible endogenous SALL4 expression. As shown in Figure 6c and e, both SALL4A and SALL4B overexpression could significantly increase c-Myc protein and mRNA expression. These data suggest that SALL4 can directly regulate c-Myc in endometrial cancer.

Figure 6. C-Myc is a direct target of SALL4 in endometrial carcinoma.

(a) ChIP-on-Chip analysis of SALL4 binding on c-Myc promoter region in NB4 cells. (b) ChIP-qPCR assay performed using SALL4-specific antibody in AN3CA cells to verify ChIP-on-Chip result. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR using specific primers. qChIP values were expressed as percentage of input chromatin as reported by others31. Data represent the average and standard deviation from three parallel experiments. (c) Western blot demonstrates that SALL4 depletion significantly down-regulated c-Myc expression in AN3CA and HEC-1A cell lines, and overexpression of SALL4 up-regulated c-Myc expression in Ishikawa cells. (d, e) Real time RT-PCR analysis reveals that the mRNA of c-Myc is affected by SALL4 in AN3CA, HEC-1A and Ishikawa ((*p<0.05).

Discussion

It has been proposed that human pre-implantation embryonic cells share similar phenotypes with cancer cells. Both types of cells are at a proliferative stem/undifferentiated cell state and are potentially immortal. Furthermore, cancer with an ES cell gene expression signature has poor prognosis 3. We and others have shown that Sall4 is a key factor of the transcriptional core network essential for the maintenance of the stemness of ES cells 14, 15. SALL4 is also abnormally expressed in germ cell tumors and has been proposed as a diagnostic marker for these tumors 8. However, more comprehensive and systematic studies on the functional role(s) of SALL4 in human solid tumors such as endometrial cancer are still lacking.

In this study, we set out to test our hypothesis that SALL4 is re-expressed in solid cancer cells and contributes to cancer cell tumorigenic properties, focusing on the endometrial cancer model. Our study suggests that SALL4 is re-expressed in almost half of the endometrial cancers at both the mRNA and protein levels, but not in the pre-neoplastic endometrial hyperplasia or normal endometrial tissues. More importantly, our clinical data combined with GESA analysis also support that aberrant SALL4 expression is positively correlated with aggressive tumor features including worse survival, increased metastasis and advanced tumor stages. Using gain- and loss-of-functional studies, we further confirmed the essential role of SALL4 in cancer cell survival, metastasis, and drug resistance of endometrial cancer. Indeed, from our immunohistochemistry study, we observed elevated SALL4 expression in 47.7% of endometrial carcinoma (n=113) were positive for SALL4 expression (Table S1).

The ability of tumor cells to acquire metastatic potential and spread in their host organism is one of the main issues in cancer treatment, as metastasis accounts for more than 90% of human cancer-related deaths 16. Our correlation study on SALL4 expression and other clinicopathological characteristics of the endometrial cancer patients reveals a positive correlation between high SALL4 expression and poor patient survival, and our GSEA data have suggested that SALL4 is positively correlated with tumor metastatic capacity in addition to poor patient survival. Furthermore, both our in vitro cell culture and in vivo murine data have confirmed that SALL4 expression is critical for tumor invasive capacity, metastatic ability, and survival of the xenotransplant recipient mice. This suggests that SALL4 can be a potential therapeutic target and blocking the oncogenic role of SALL4 could potentially benefit patients with more advanced endometrial cancer, whose prognosis are very poor in general with a median survival of less than 1 year 17. Future studies are needed to test this potential.

Another challenging hurdle in cancer therapy is chemoresistance. C-Myc is frequently overexpressed in a wide range of human cancers, including endometrial carcinoma 18–20. In addition, the role of c-Myc in tumor metastasis and drug resistance has been extensively studied 21–24. In this report, we have demonstrated that c-Myc is one of SALL4 target genes by ChIP-qPCR assay. Furthermore, our loss- and gain-of-function studies have shown that c-Myc expression level is regulated directly by SALL4, and manipulation of SALL4 expression can affect drug sensitivity of endometrial cancer cells. Therefore, we propose that c-Myc is one of the key target genes of SALL4 in endometrial cancer, which could contribute, at least in part, to SALL4-mediated metastasis and drug resistance. Since SALL4 is also involved in leukemia and other solid tumors, it is will be interesting to test whether the SALL4/c-Myc pathway could be a general property of SALL4-mediated tumorigenisis.

In summary, our study has revealed the following novel and important findings: (I) SALL4 is not expressed in normal or hyperplastic endometrial, but is aberrantly expressed in 47.7% of endometrial carcinoma, and its expression was positively correlated with aggressive tumor features; (II) SALL4 is critical for endometrial cancer cell survival, drug resistance and tumor progression. As a consequence of being an oncofetal protein with functional roles in cancer cell and absence in normal tissue, SALL4 represents an attractive novel drug target for the high risk endometrial cancer patient population, similar to what we have reported for aggressive hepatocellular carcinomas 25. Overall, our finding provides novel insight to the mechanism and potential therapeutic target for endometrial cancer patients.

Materials and Methods

Patient samples

Twenty one cases of normal endometrial tissues, five cases of endometrial hyperplasia and 113 cases of endometrial carcinoma tissues from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the National University Hospital (NUH) of Singapore were selected for the study. Ethics approval was obtained from Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board (2011-P-000096/1) as well as from the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board (NUS IRB 09-261).

SALL4 immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis

Immunohistochemical staining was performed according to standard techniques. Briefly, paraffin tissue sections of 4μm were deparaffinized with Histoclear and hydrated in graded ethanols. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling at 120°C in high pH target retrieval solution for 10 minutes in a pressure cooker. Primary antibodies were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour in a humidified chamber, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature. Antibody binding was revealed by DAB and reaction was stopped by immersion of tissue sections in distilled water once brown color appeared. Tissue sections were counterstained by hematoxylin, dehydrated in graded ethanol and mounted. Monoclonal anti-SALL4 antibody (Santa Cruz, CA, USA #sc-101147) was used. All reagents for immunohistochemistry were from Dako (Dako, Denmark A/S). Appropriate positive and negative controls were included for each run of IHC. For IHC on TMAs, SALL4 expression was scored according to the percentage of tumor cells stained positive for SALL4, with 0 denoting less than 5% of tumor cells stained, +1 denoting 5 – 30% of tumor cells stained, +2 denoting 31 – 50% of tumor cells stained, +3 denoting 51 – 80% of tumor cells stained.

Lentiviral constructs and lentivirus generation

Human SALL4A or SALL4B fragments were subcloned into a modified lentiviral vector (FUW-Luc-mCh-puro) with mCherry and puromycin selection markers (Figure S5a). SALL4A or SALL4B mutant preserving the same amino acid sequence, but containing triple-point mutations within the SALL4shRNA1 target nucleotide sequence which renders the transgenes resistant to SALL4 shRNA targeting, were generated using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and confirmed by sequencing. Short hairpin RNAs set for human SALL4 in pLKO.1-puro vector were purchased from Open Biosystems (RHS3979) and knockdown efficiency was further evaluated. Two of them, designated as SALL4shRNA1 and SALL4shRNA 2, were selected for subsequent experiments. The sequences for SALL4 shRNAs and scrambled shRNA are listed as following: SALL4shRNA1: GCCTTGAAACAAGCCAAGCTA; SALL4shRNA 2: CTATTTAGCCAAAGGCAAA; Scr-shRNA: CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCG

Cell culture

Cell lines AN3CA, HEC-1A, and KLE were kindly provided by Dr. Patricia Donahoe (Massachusetts General Hospital, MA, USA) 26. HEC-1B, Ishikawa, RL-95-2 and SKUTB were kindly provided by Dr. Immaculata De Vivo (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, MA, USA) 27. Cell lines were maintained in a 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator. DMEM, McCoy’s 5A, EME, and DMEM-F12 growth media along with supplements were purchased from Gibco-Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Cells were infected at various multiplicities of infection with lentivirus expressing SALL4 or SALL4shRNAs, and then selected with puromycin for three days. Then cells were harvested for western blot and subsequent functional studies.

Western blot

Whole-cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer [1% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM sodiumfluoride, 30mM sodium, pyrophosphate, 2 mM sodium molybdate, 5 mM EDTA, and 2 mM sodium orthovanadate] containing protease inhibitors (10 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Protein concentrations were determined by using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay. 30μg of protein was loaded on a 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (NuPAGE; Invitrogen) and blotted onto a nylon membrane. Adequate protein transfer was demonstrated by staining the membranes with Ponceau S (Sigma Chemical). The following primary antibodies were used for staining: antibody raised against SALL4 (mouse monoclonal, Santa Cruz Inc SC-101147), anti-c-Myc (Rabbit polyclonal, cell signaling D84C12) and α-tubulin (mouse monoclonal Sigma T6074). Detection was by ECL (Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology) with a Fuji LAS1000 Plus chemiluminescence imaging system.

Wound-healing, Migration and Invasion assays

An artificial “wound” was created on a confluent cell monolayer and photographs were taken at the indicated time. A permeable filter of transwell system (8-μm pores size, Transwell Permeable supports, Cat. No.3422, Corning Incoporated, MA) was used for migration assays and 24-well plates with Matrigel-coated inserts (8-μm pores; BD Biosciences) were used for matrigel invasion assays. After puromycin selection, shRNAs-infected cells were added to inserts in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were incubated for the indicated time periods under standard culture conditions. Tumor cells remaining on the top-side of the membrane were removed by cotton swab. Cells that migrated to the underside were fixed and stained with crystal violet solution. After taking pictures, the stained cells were solubilized with 10% acetic acid and quantitated on a microplate reader at 600nm.

Xenotransplant murine models

All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines set forth by the Children’s Hospital Boston (CHB animal protocol number 11-09-2022). Eight to ten-week-old NOD/SCID mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility. To generate a subcutaneous xenograft mouse model, NOD/SCID mice were injected subcutaneously with 2×106 cells into right flanks. Cells were resuspended in 0.1 ml of PBS and then mixed with 0.1ml of matrigel. Tumor sizes were measured weekly. For development of the i.p. injection xenograft model, ten million cells, suspended in 500ul of phosphate-buffered saline, were injected with a 25-gauge needle into the peritoneal cavity of NOD/SCID mice and disease progression was monitored based on overall health status of the recipient mice. As for the metastatic mouse model, one million 1×106 AN3CA cells were injected via the retro-orbital sinus route as a method of i.v. xenotransplant model described previously. After 6 weeks, mice were euthanized and organs were checked for metastasis. Tissues of the liver, lung, spleen, and kidney were collected and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for further routine histology examination by hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E.). Tissue sections were also stained with anti-GFP antibody (Abcam, Cat. No. ab6556). The antibody was utilized at 1:400 in a Leica Bond-III autostainer using the Bond Polymer Refine Detection kit according to manufacturer’s protocol. Cell proliferation in the tumors was determined by staining histological sections with monoclonal antibody against Ki-67 (BD, Cat. No.556003), and apoptosis was evaluated by terminal uridine deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (in situ cell death detection kit, Promega, Cat. No. G3250) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Cell proliferation and apoptosis

Cell proliferation was monitored by the MTS assay as described29, and BrdU incorporation assay. The BD Pharmingen BrdU flow kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was used. BrdU was added up to 1 hour before harvesting of cells, and incorporation to the cells was assessed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Simultaneous staining of DNA with 7-amino-actinomycin D was used in combination with BrdU, followed by two-color flow cytometric analysis. Apoptosis was assayed by AnnexinV kit following a protocol from the supplier (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

qChIP (Chromatin immunoprecipitation) and qRT-PCR

AN3CA cells were grown and processed for qChIP as described previously 30 using an anti-SALL4 antibody. Real-time PCR was performed with two sets of c-Myc primers (Table S3) to validate pulldown DNA fragment. Normal IgG was used as a negative control. Total RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) or RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Real-time PCR for SALL4A and B was performed with the TaqMan PCR core reagent kit (Applied Biosystems) as described previously 7. C-Myc mRNA expression was measured using iScript One-step RT-PCR Kit with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad). C-Myc primers are as follows: Forward 5′TCAAGAGGCGAACACACAAC-3′; Reverse: 5′-GGCCTTTTCATTGTTTTCCA-3′.

GSEA analysis

Gene expression data of endometrial carcinoma was extracted from the GEO database (Accession number: GSE21882). Prior to GSEA, all EC samples were divided into two groups according to their SALL4 expression: SALL4 high and SALL4 low. GSEA was then performed based on normalized data using GSEA v2.0 tool (http://www.broad.mit.edu/gsea/) for identification of enriched gene sets between SALL4 high & SALL4 low groups.

Chemoresistance assay

Carboplatin was purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. C2538). Cultured cells were plated in 6-well plates to allow for colony formation for 2–3 weeks, or cells were seeded on coverslips overnight. Then, cells were treated with indicated dosages of carboplatin for 72 hours. Cell proliferation and apoptosis were evaluated by MTS assay, Ki-67 staining or TUNEL assay respectively as described above.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance between two groups was determined by student t-test or Pearson’s chi-squared test (χ2) test (GraphPad Prism 5.0 Software). Log-rank test was used for survival analysis. The value of p<0.05 was considered significant (*).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part through NIH grants PO1DK080665, NIH RO1HL092437, and PO1HL095489 (to LC). We also want to thank Nicole Tenen, Joline Lim in assisting the preparation of the manuscript and Xi Tian in helping with mouse work.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc).

References

- 1.Amant F, Moerman P, Neven P, Timmerman D, Van Limbergen E, Vergote I. Endometrial Cancer. Lancet. 2005;366:491–505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saso S, Chatterjee J, Georgiou E, Ditri AM, Smith JR, Ghaem-Maghami S. Endometrial Cancer. BMJ. 2011;343:d3954. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.You JS, Kang JK, Seo DW, Park JH, Park JW, Lee JC, et al. Depletion of Embryonic Stem Cell Signature by Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor in Nccit Cells: Involvement of Nanog Suppression. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5716–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, et al. An Embryonic Stem Cell-Like Gene Expression Signature in Poorly Differentiated Aggressive Human Tumors. Nat Genet. 2008;40:499–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elling U, Klasen C, Eisenberger T, Anlag K, Treier M. Murine Inner Cell Mass-Derived Lineages Depend on Sall4 Function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16319–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607884103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakaki-Yumoto M, Kobayashi C, Sato A, Fujimura S, Matsumoto Y, Takasato M, et al. The Murine Homolog of Sall4, a Causative Gene in Okihiro Syndrome, Is Essential for Embryonic Stem Cell Proliferation, and Cooperates with Sall1 in Anorectal, Heart, Brain and Kidney Development. Development. 2006;133:3005–13. doi: 10.1242/dev.02457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma Y, Cui W, Yang J, Qu J, Di C, Amin HM, et al. Sall4, a Novel Oncogene, Is Constitutively Expressed in Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia (Aml) and Induces Aml in Transgenic Mice. Blood. 2006;108:2726–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao D, Humphrey PA, Allan RW. Sall4 Is a Novel Sensitive and Specific Marker for Metastatic Germ Cell Tumors, with Particular Utility in Detection of Metastatic Yolk Sac Tumors. Cancer. 2009;115:2640–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi D, Kuribayashi K, Tanaka M, Watanabe N. Overexpression of Sall4 in Lung Cancer and Its Importance in Cell Proliferation. Oncology reports. 2011;26:965–70. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi D, Kuribayshi K, Tanaka M, Watanabe N. Sall4 Is Essential for Cancer Cell Proliferation and Is Overexpressed at Early Clinical Stages in Breast Cancer. International journal of oncology. 2011;38:933–9. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levan K, Partheen K, Osterberg L, Olsson B, Delle U, Eklind S, et al. Identification of a Gene Expression Signature for Survival Prediction in Type I Endometrial Carcinoma. Gene expression. 2010;14:361–70. doi: 10.3727/105221610x12735213181242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, Chai L, Fowles TC, Alipio Z, Xu D, Fink LM, et al. Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Sall4 to Be a Major Regulator of Pluripotency in Murine-Embryonic Stem Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19756–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J, Chai L, Gao C, Fowles TC, Alipio Z, Dang H, et al. Sall4 Is a Key Regulator of Survival and Apoptosis in Human Leukemic Cells. Blood. 2008;112:805–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-126326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Tam WL, Tong GQ, Wu Q, Chan HY, Soh BS, et al. Sall4 Modulates Embryonic Stem Cell Pluripotency and Early Embryonic Development by the Transcriptional Regulation of Pou5f1. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1114–23. doi: 10.1038/ncb1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Q, Chen X, Zhang J, Loh YH, Low TY, Zhang W, et al. Sall4 Interacts with Nanog and Co-Occupies Nanog Genomic Sites in Embryonic Stem Cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24090–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehlen P, Puisieux A. Metastasis: A Question of Life or Death. Nature reviews. 2006;6:449–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elit L, Hirte H. Current Status and Future Innovations of Hormonal Agents, Chemotherapy and Investigational Agents in Endometrial Cancer. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2002;14:67–73. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200202000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao DJ, Dickson RB. C-Myc in Breast Cancer. Endocrine-related cancer. 2000;7:143–64. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0070143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Little CD, Nau MM, Carney DN, Gazdar AF, Minna JD. Amplification and Expression of the C-Myc Oncogene in Human Lung Cancer Cell Lines. Nature. 1983;306:194–6. doi: 10.1038/306194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borst MP, Baker VV, Dixon D, Hatch KD, Shingleton HM, Miller DM. Oncogene Alterations in Endometrial Carcinoma. Gynecologic oncology. 1990;38:364–6. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90074-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knapp DC, Mata JE, Reddy MT, Devi GR, Iversen PL. Resistance to Chemotherapeutic Drugs Overcome by C-Myc Inhibition in a Lewis Lung Carcinoma Murine Model. Anti-cancer drugs. 2003;14:39–47. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Waardenburg RC, Prins J, Meijer C, Uges DR, De Vries EG, Mulder NH. Effects of C-Myc Oncogene Modulation on Drug Resistance in Human Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Cell Lines. Anticancer research. 1996;16:1963–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolfer A, Wittner BS, Irimia D, Flavin RJ, Lupien M, Gunawardane RN, et al. Myc Regulation of A “Poor-Prognosis” Metastatic Cancer Cell State. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;107:3698–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914203107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hermeking H. The Myc Oncogene as a Cancer Drug Target. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2003;3:163–75. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yong KJ, Gao C, Lim JS, Yan B, Yang H, Dimitrov T, et al. Oncofetal gene SALL4 in aggressive hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2266–2276. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renaud EJ, MacLaughlin DT, Oliva E, Rueda BR, Donahoe PK. Endometrial Cancer Is a Receptor-Mediated Target for Mullerian Inhibiting Substance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:111–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407772101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong JY, Huggins GS, Debidda M, Munshi NC, De Vivo I. Dichloroacetate Induces Apoptosis in Endometrial Cancer Cells. Gynecologic oncology. 2008;109:394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Criscuoli ML, Nguyen M, Eliceiri BP. Tumor Metastasis but Not Tumor Growth Is Dependent on Src-Mediated Vascular Permeability. Blood. 2005;105:1508–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong HW, Cui W, Yang Y, Lu J, He J, Li A, et al. Sall4, a Stem Cell Factor, Affects the Side Population by Regulation of the Atp-Binding Cassette Drug Transport Genes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J, Chai L, Liu F, Fink LM, Lin P, Silberstein LE, et al. Bmi-1 Is a Target Gene for Sall4 in Hematopoietic and Leukemic Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10494–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank SR, Schroeder M, Fernandez P, Taubert S, Amati B. Binding of C-Myc to Chromatin Mediates Mitogen-Induced Acetylation of Histone H4 and Gene Activation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2069–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.906601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.