Abstract

Background

Health agencies across the world have echoed the recommendation of the U.S. Institute of Medicine (iom) that survivorship care plans (scps) should be provided to patients upon completion of treatment. To date, reviews of scps have been limited to the United States. The present review offers an expanded scope and describes how scps are being designed, delivered, and evaluated in various countries.

Methods

We collected scps from Canada, the United States, Europe, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. We selected for analysis the scps for which we could obtain the actual scp, information about the delivery approach, and evaluation data. We conducted a content analysis and compared the scps with the iom guidelines.

Results

Of 47 scps initially identified, 16 were analyzed. The scps incorporated several of the iom’s guidelines, but many did not include psychosocial services, identification of a key point of contact, genetic testing, and financial concerns. The model of delivery instituted by the U.K. National Cancer Survivorship Initiative stands out because of its unique approach that initiates care planning at diagnosis and stratifies patients into a follow-up program based on self-management capacities.

Summary

There is considerable variation in the approach to delivery and the extent to which scps follow the original recommendations from the iom. We discuss the implications of this review for future care-planning programs and prospective research. A holistic approach to care that goes beyond the iom recommendations and that incorporates care planning from the point of diagnosis to beyond completion of treatment might improve people’s experience of cancer care.

Keywords: Supportive care, survivorship care plans, survivorship

1. INTRODUCTION

At an estimated 22.4 million worldwide, the number of people living with and beyond cancer is higher than ever because of advancements in treatment, early detection, screening, and prevention of secondary cancers1–3. In Canada and the United Kingdom, about 1 and 2 million people respectively are currently living with and beyond cancer4–7. In the United States, the number of survivors rose to 11.7 million in 2007 from 3 million in 19718. Of the U.S. survivors, approximately 67% live at least 5 years after receiving their diagnosis, and 10% live 25 years or longer1,8.

These survivorship numbers are encouraging, but they also signal a global trend requiring attention. Implicit in that trend is the fact that people continue to face challenges once treatment is complete. Those challenges arise in the physical, psychological, economic, and spiritual domains and include issues such as fatigue, fear of recurrence, and uncertainty regarding next steps2. As a result, research that strives to broaden the understanding of those issues and of how to better support people affected by cancer has been on the increase.

One such line of research explores the value of a personalized record of care and a follow-up plan—often called a survivorship care plan (scp)—as a means of improving patient-reported and health-related outcomes such as distress, self-efficacy, and quality of life. The U.S. Institute of Medicine (iom) recommends that, as part of optimal survivorship care, a scp should be provided to every patient upon completion of treatment2. The scp can include summaries of the patient’s cancer type and treatment history, schedules for possible follow-up screening, potential post-treatment issues, signs of recurrence, guidelines for lifestyle modifications, and important community resources. This information can offer people direction during the transition from active treatment at a cancer centre back to a primary health care provider (hcp) in the community, a period characterized by many researchers and practitioners as lacking in coordination9–12. Survivorship care plans can also help patients to communicate better with community hcps, ensure that patients receive the appropriate follow-up care in a timely manner, and support patients in dealing with the effects of their disease and treatments2,13,14.

The iom recommendations have been echoed, to varying degrees, by select government bodies worldwide, including the Australian Department of Health15, the National Cancer Survivorship Initiative (ncsi) in the United Kingdom5, and the Dutch Health Council16. In 2009, the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, an independent organization created and funded by the federal government, made survivorship and scps a practice and research priority. In view of the increasing number of organizations throughout the world that have already incorporated or are considering the adoption of scps, and also the strong support from patients in many jurisdictions14,17,18, there is a need to understand and describe the many variations in the features of scps from various regions.

We conducted a review of English-language scps for adults with cancer that had been created and evaluated before April 2012. Few reviews of existing scps had been undertaken before this one, and of those that had, most had been limited to scps used in U.S. cancer centres14,19,20 and to particular cancer types, such as breast cancer19. Our review aimed to extend that body of knowledge by including scps used on other continents in both research and clinical settings. We were guided by these questions:

What are the contents of current English-language scps?

What are their accompanying implementation strategies?

What are the results of any evaluations of the scps after implementation?

This paper reports the findings of our review. It describes the variation in content, methods of delivery, and evaluations of English-language scps offered in various countries, and it compares our findings with the iom’s recommended elements of a scp2. We conclude by discussing an approach to care that moves the focus from the end of treatment (survivorship) to a broader supportive care approach that incorporates features of scps throughout the cancer care continuum.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search Strategies

We used several methods to identify English-language scps or organizations or authors that have used or produced scps. Our approach was inclusive and strategic; we strived to collect scps representative of diverse locations, while working within a limited time frame (3 months) and with limited resources. To locate scps, we conducted Google Scholar, medline, and cinahl searches using the key words “survivorship care plans,” “follow-up care,” “treatment summaries,” and “post-treatment.” We searched for any English-language scps from Canada, the United States, Europe, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. We examined the Web sites of all Canadian provincial cancer agencies and treatment centres, and the Web sites of all 2011 U.S. National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centres in the United States. In addition, we probed the Web sites of key cancer organizations and foundations, including the Canadian Cancer Society, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the livestrong Foundation, U.S. National Cancer Institute, the Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre, and Macmillan Cancer Support.

2.2. Identifying and Locating SCPs

We created a working definition of a scp based on the iom’s “elements of a survivorship care plan” criteria2: written documents designed for use by adult cancer patients that contain at least one element from each of the record of care and follow-up care plan components. Using this working definition as the inclusion criteria, we separated general patient information materials (such as general post-treatment information booklets21–23) from documents that had the elements of a scp, and we focused our attention on the latter.

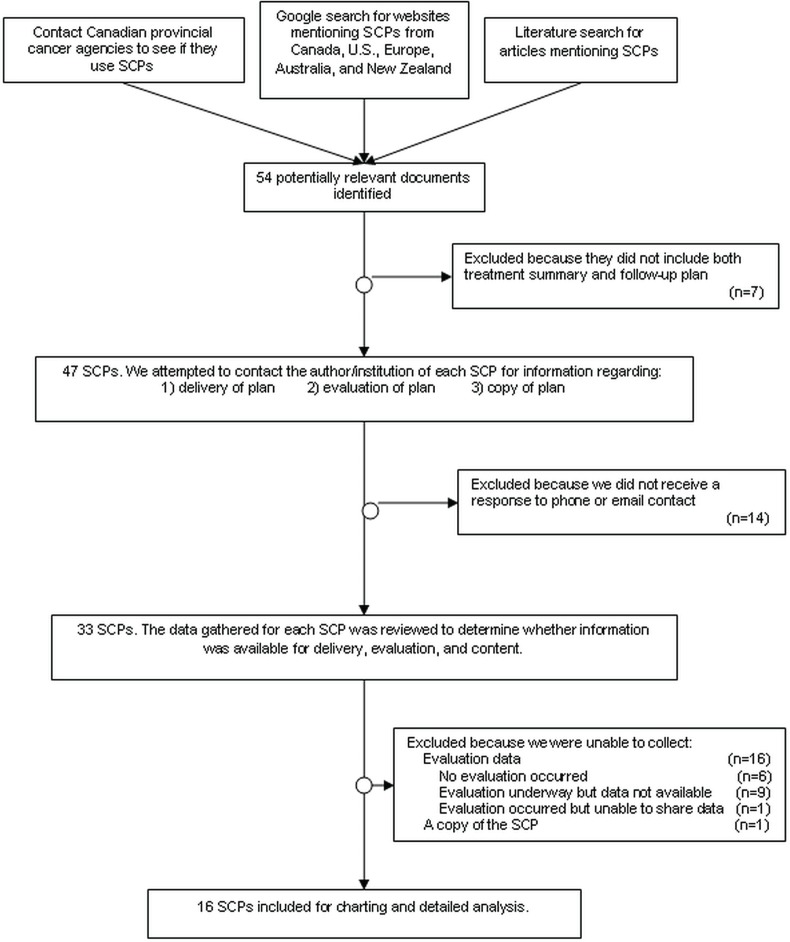

Once we identified existing scps, we attempted to collect the actual scp documents and any available information on their method of delivery and evaluation by contacting the applicable author or organization by e-mail or telephone. We assured all contacts that any unpublished information would not be linked to their specific institution. We fully analyzed only scps for which we could obtain a copy of the plan, information about delivery, and information about evaluation. Figure 1 summarizes the search strategies and inclusion/exclusion process. This study was considered quality assurance work and was exempt from research ethics board review.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of survivorship care plan (scp) search strategies and inclusion decisions.

2.3. Analysis of SCPs

We performed a content analysis24 of the scps, their methods of delivery, and their evaluation data, tracking the content categories on a spreadsheet. Two groups of researchers analyzed and verified the analyses, one group performing the initial analysis, and the second group acting as reviewer. The resulting spreadsheet was used to summarize the data and to extract and interpret common themes.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Context

Of the 47 scps identified, 16 for which we could ascertain content, delivery, and evaluation information were examined in detail. Table i summarizes the general characteristics of the analyzed scps. Although usually titled “survivorship care plan” and generally covering similar content, the details of each plan varied. Each site instituting a scp created a plan that met their unique needs, and there were often specific versions for particular cancer types. Although for the purpose of summarizing the plans, we examined the content of the scps separately from the methods of delivery, the content and method of delivery of most scps are linked and should not be viewed independently. Nearly all the documents that we examined were part of an approach that involved, at minimum, a conversation with a hcp. Information might not have been included in the content of the written scp document, but might have been discussed during the post-treatment meeting or attached in a pamphlet.

TABLE I.

General characteristics of survivorship care plans

| Characteristic |

Survivorship care plans

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Identified (n=47) | Analyzed (n=16) | |

| Type of organization responsible for development | ||

| Single-location treatment centre or hospital | 17 | 4 |

| Multi-location treatment centre or agency | 16 | 5 |

| Nongovernment nonprofit organization | 3 | 1 |

| Government body | 2 | 0 |

| Collaboration of multiple organizations | 9 | 6 |

| Country of development | ||

| United States | 32 | 11 |

| Canada | 7 | 3 |

| Australia | 6 | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 1 | 1 |

| Netherlands | 1 | 0 |

| Tumour site | ||

| Breast | 14 | 4 |

| Colorectal | 3 | 0 |

| Prostate | 1 | 0 |

| Hemopoietic (blood) | 1 | 1 |

| Gynecologic (ovarian/endometrial) | 1 | 0 |

| Multiple tumour sites | 27 | 11 |

| Type of distribution | ||

| In use in one or more clinics | 27 | 9 |

| Used as part of research or pilot project | 12 | 4 |

| Created using free online software | 3 | 2 |

| Template made available online | 5 | 1 |

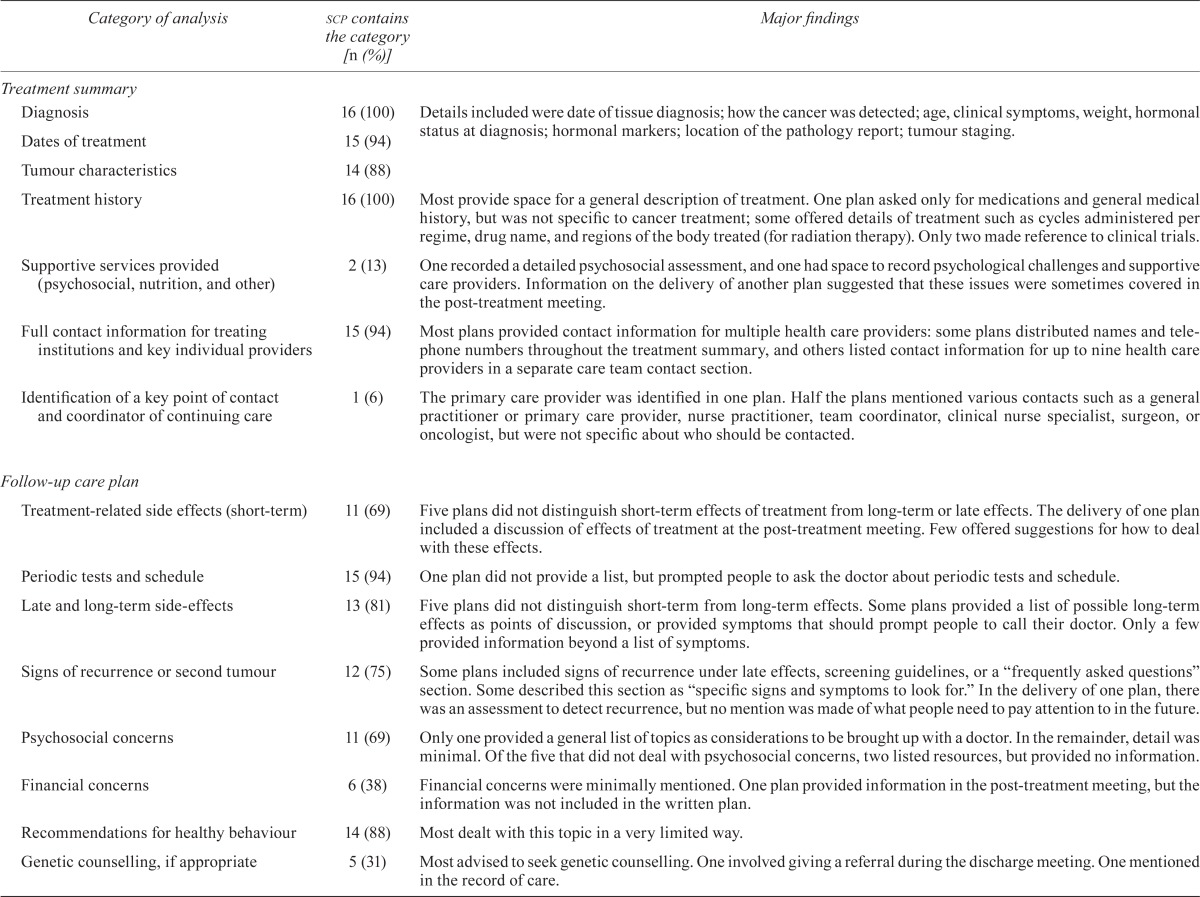

3.2. Content of SCPs

We analyzed content based on our interpretation of the 18 sections of the iom framework (p. 152–3)2. Table ii summarizes the 18 sections of the iom framework, the criteria that we developed to determine if each component was present, and the number of scps that included the particular component. Table iii summarizes our findings for each component.

TABLE II.

Content of survivorship care plans: categories of analysis

| Category of analysisa | Criteria for determining if category was present |

|---|---|

| Treatment summary | |

| Diagnosis | Mention of diagnosis |

| Dates of treatment | Mention of dates of treatment |

| Tumour characteristics | Any mention of tumour site, size, stage, (Gleason) score, nodes, pathology findings, hormonal markers (applicable for some specific tumour sites), hematology, stem-cell transplantation |

| Treatment history | Mention of treatments received (that is, surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy, others) |

| Supportive services provided (psychosocial, nutrition, others) | Mention of any supportive services provided during treatment |

| Full contact information for treating institutions and key individual providers | Name of treating health care provider and contact information for the treating centre (or the direct telephone number of the treating health care provider) |

| Identification of a key point of contact and coordinator of continuing care | Mention of coordinator of continuing care |

| Follow-up care plan | |

| Treatment-related side effects (short-term) | Mention of any short-term (side) effects of treatment or the likely course of recovery |

| Periodic tests and schedule | Suggestions of tests that are needed in the coming months and years |

| Late and long-term side-effects | Mention of late or long-term effects and how to deal with them |

| Signs of recurrence or second tumour | Mention of signs and symptoms of recurrence |

| Psychosocial concerns | Reference in the care plan to effects on sexual functioning, relationships, anxiety, fatigue, sadness, depression |

| Financial concerns | Any mention of financial issues (insurance, cost of medication, work) |

| Recommendations for healthy behaviour | Any mention of variations in after-treatment care, self-management, or lifestyle |

| Genetic counselling, if appropriate | Mention of genetic testing as part of follow-up care, including referrals |

| Chemoprevention, if appropriate | Any mention of possible future cause for preventive pharmaceutical therapies (for example, tamoxifen, aspirin) |

| Referrals | Any referrals to specific care providers (including primary care providers or support groups) |

| Resource lists | Any lists of cancer-related information and resources (Internet- or telephone-based) |

Based on recommendations from the U.S. Institute of Medicine2.

TABLE III.

Content of survivorship care plans: major findings from 16 plans

| Category of analysis | scp contains the category [n (%)] | Major findings |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment summary | ||

| Diagnosis | 16 (100) | Details included were date of tissue diagnosis; how the cancer was detected; age, clinical symptoms, weight, hormonal status at diagnosis; hormonal markers; location of the pathology report; tumour staging. |

| Dates of treatment | 15 (94) | |

| Tumour characteristics | 14 (88) | |

| Treatment history | 16 (100) | Most provide space for a general description of treatment. One plan asked only for medications and general medical history, but was not specific to cancer treatment; some offered details of treatment such as cycles administered per regime, drug name, and regions of the body treated (for radiation therapy). Only two made reference to clinical trials. |

| Supportive services provided (psychosocial, nutrition, and other) | 2 (13) | One recorded a detailed psychosocial assessment, and one had space to record psychological challenges and supportive care providers. Information on the delivery of another plan suggested that these issues were sometimes covered in the post-treatment meeting. |

| Full contact information for treating institutions and key individual providers | 15 (94) | Most plans provided contact information for multiple health care providers: some plans distributed names and telephone numbers throughout the treatment summary, and others listed contact information for up to nine health care providers in a separate care team contact section. |

| Identification of a key point of contact and coordinator of continuing care | 1 (6) | The primary care provider was identified in one plan. Half the plans mentioned various contacts such as practitioner or primary care provider, nurse practitioner, team coordinator, clinical nurse specialist, surgeon, or oncologist, but were not specific about who should be contacted. |

| Follow-up care plan | ||

| Treatment-related side effects (short-term) | 11 (69) | Five plans did not distinguish short-term effects of treatment from long-term or late effects. The delivery of one plan included a discussion of effects of treatment at the post-treatment meeting. Few offered suggestions for how to deal with these effects. |

| Periodic tests and schedule | 15 (94) | One plan did not provide a list, but prompted people to ask the doctor about periodic tests and schedule. |

| Late and long-term side-effects | 13 (81) | Five plans did not distinguish short-term from long-term effects. Some plans provided a list of possible long-term effects as points of discussion, or provided symptoms that should prompt people to call their doctor. Only a few provided information beyond a list of symptoms. |

| Signs of recurrence or second tumour | 12 (75) | Some plans included signs of recurrence under late effects, screening guidelines, or a “frequently asked questions” section. Some described this section as “specific signs and symptoms to look for.” In the delivery of one plan, there was an assessment to detect recurrence, but no mention was made of what people need to pay attention to in the future. |

| Psychosocial concerns | 11 (69) | Only one provided a general list of topics as considerations to be brought up with a doctor. In the remainder, detail was minimal. Of the five that did not deal with psychosocial concerns, two listed resources, but provided no information. |

| Financial concerns | 6 (38) | Financial concerns were minimally mentioned. One plan provided information in the post-treatment meeting, but the information was not included in the written plan. |

| Recommendations for healthy behaviour | 14 (88) | Most dealt with this topic in a very limited way. |

| Genetic counselling, if appropriate | 5 (31) | Most advised to seek genetic counselling. One involved giving a referral during the discharge meeting. One mentioned in the record of care. |

| Chemoprevention, if appropriate | 1 (6) | One included current use of hormone therapy in the record of care and discussed future possible needs in the record of care. |

| Referrals | 10 (63) | Many suggested the person to contact within specific sections of the plan. Two organizations provided referrals in the discharge meeting, although they did not record these in the plans. |

| Resource lists | 8 (50) | Listed resources included Web sites, seminars, telephone listings, books, and videos. Of the organizations that did not list resources within the care plan, several provided separate lists to patients. |

3.3. Methods of Delivery of SCPs

There was considerable variability in delivery style for the 16 analyzed documents. However, most plans were delivered at face-to-face clinic visits or discharge meetings by a nurse or nurse practitioner after the patient had completed active treatment. Many organizations provided additional materials to supplement the care plan document, including brochures, booklets, and a list of answers to frequently asked questions. In most cases, the resources given depended on particular patient concerns expressed at the post-treatment meeting. Table iv summarizes the main characteristics of the various delivery approaches.

TABLE IV.

Delivery of survivorship care plans

| Characteristic | (n of 16) |

|---|---|

| How is the plan provided? | |

| In person or by mail or e-mail after an in- person meeting | 14 |

| Web-based (created online) | 2 |

| Who delivers the plan? | |

| Registered nurse or nurse practitioner | 7 |

| Team of multidisciplinary health care providers | 4 |

| Self-administered by patient | 2 |

| Oncologist | 1 |

| Late-effects clinician | 1 |

| Trained volunteer | 1 |

| When is the plan delivered? | |

| After completion of active treatment | 10 |

| Flexibility in timing is allowed | 5 |

| Near diagnosis AND at end of treatment | 1 |

| Is a copy given to other health care providers? | |

| Yes | 10 |

| No, but patients are encouraged to share their copy | 2 |

| Not known | 4 |

| Is there any follow-up after delivery? | |

| Yes | 4 |

| No | 2 |

| At discretion of patient | 5 |

| Not known | 5 |

| Are any additional resources given? | |

| Yes | 9 |

| No | 2 |

| Not known | 5 |

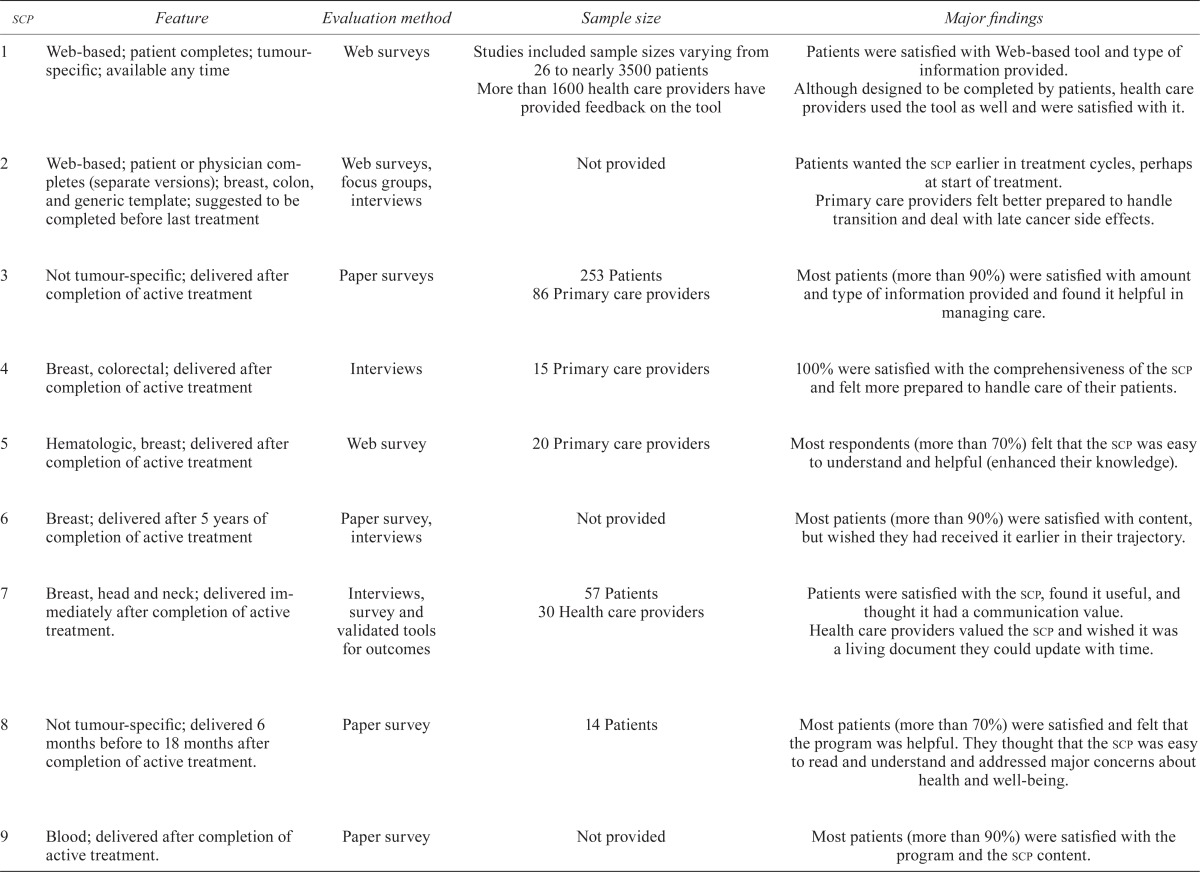

3.4. Evaluations of SCPs

Evaluation of scps is an emerging area of research, and many projects are still in their early stages. In addition to the 16 scps for which we obtained evaluation data, we also communicated with researchers and practitioners from 9 other organizations who were in the process of conducting evaluations, but did not have data to share as of spring 2012.

The 16 evaluation reports that we analyzed varied in sample size and method of evaluation17,25,26. Most of the evaluation data were obtained through non-validated surveys. Only 7 of the 16 organizations that shared their evaluation data had published their results; the other 9 organizations shared unpublished data.

Usefulness ratings for the scps varied between 80% and 95% in the published studies25,27,28. Interestingly, some of the feedback emphasized the need for patients to be provided with this information earlier in the cancer treatment trajectory, suggesting that the information and support given to people at the end of treatment would also be useful to them throughout their treatment29–31. Table v summarizes the evaluation data.

TABLE V.

Features, evaluation characteristics, and major findings for 16 survivorship care plans (scps)

| scp | Feature | Evaluation method | Sample size | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Web-based; patient completes; tumour-specific; available any time | Web surveys | Studies included sample sizes varying from 26 to nearly 3500 patients More than 1600 health care providers have provided feedback on the tool | Patients were satisfied with Web-based tool and type of information provided. Although designed to be completed by patients, health care providers used the tool as well and were satisfied with it. |

| 2 | Web-based; patient or physician completes (separate versions); breast, colon, and generic template; suggested to be completed before last treatment | Web surveys, focus groups, interviews | Not provided | Patients wanted the scp earlier in treatment cycles, perhaps at start of treatment. Primary care providers felt better prepared to handle transition and deal with late cancer side effects. |

| 3 | Not tumour-specific; delivered after completion of active treatment | Paper surveys | 253 Patients 86 Primary care providers |

Most patients (more than 90%) were satisfied with amount and type of information provided and found it helpful in managing care. |

| 4 | Breast, colorectal; delivered after completion of active treatment | Interviews | 15 Primary care providers | 100% were satisfied with the comprehensiveness of the scp and felt more prepared to handle care of their patients. |

| 5 | Hematologic, breast; delivered after completion of active treatment | Web survey | 20 Primary care providers | Most respondents (more than 70%) felt that the scp was easy to understand and helpful (enhanced their knowledge). |

| 6 | Breast; delivered after 5 years of completion of active treatment | Paper survey, interviews | Not provided | Most patients (more than 90%) were satisfied with content, but wished they had received it earlier in their trajectory. |

| 7 | Breast, head and neck; delivered immediately after completion of active treatment. | Interviews, survey and validated tools for outcomes | 57 Patients 30 Health care providers |

Patients were satisfied with the scp, found it useful, and thought it had a communication value. Health care providers valued the scp and wished it was a living document they could update with time. |

| 8 | Not tumour-specific; delivered 6 months before to 18 months after completion of active treatment. | Paper survey | 14 Patients | Most patients (more than 70%) were satisfied and felt that the program was helpful. They thought that the scp was easy to read and understand and addressed major concerns about health and well-being. |

| 9 | Blood; delivered after completion of active treatment. | Paper survey | Not provided | Most patients (more than 90%) were satisfied with the program and the scp content. |

| 10 | Prostate, breast, colorectal, lung; plan created around diagnosis, modified during treatment, and revised at the end of active treatment. | Paper and Web surveys, validated questionnaires, focus groups, interviews | Studies included sample sizes varying from 20 to nearly 72,000 patients More than 900 health care providers have been involved in pilot studies and have provided feedback (a number of reports have been published over a period of 5 years and are available at http://www.ncsi.org.uk/resources/). |

Evaluation is ongoing. Patient experiences improved with new survivorship initiatives starting at the point of diagnosis. Health care providers recognized the benefits of a holistic needs assessment, care planning, and treatment summaries. An observed reduction in unnecessary appointments and emergency admissions released health care provider capacity for patients with complex needs. |

| 11 | Breast; delivered within 2 weeks of completion of active treatment | Interviews | 5 Patients Number of primary care providers not provided |

Patients felt that written information was helpful. Primary care providers felt that the scp enhanced their knowledge and improved care provision. |

| 12 | Breast; delivered during a group visit at least 3 years after diagnosis with no metastasis. | Paper survey, conversations with clinicians | More than 160 patients Number of health care providers not provided |

Patients were satisfied with the program, but would have liked to start it earlier in their care trajectory. Health care providers were highly satisfied. |

| 13 | Not tumour-specific; delivered before completion of active treatment, sometimes at the beginning of treatment | Paper survey | 27 Patients | Most patients (more than 70%) felt that the scp was easy to use and helpful; 67% felt that it should be given at the start of treatment. |

| 14 | Breast; delivered at least 3 months after completion of treatment | Validated questionnaires for outcomes | Randomized clinical trial: 408 randomized patients (control and intervention groups) | Patients in the intervention group (receiving the scp) were more likely to correctly identify their primary care provider as being responsible for their follow-up care. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in any other patient-reported outcome investigated. |

| 15 | Not tumour-specific; delivered right after completion of active treatment, but may vary. | Paper survey | 157 Patients | Most patients (more than 90%) found the scp useful and felt that it helped them to make at least one positive lifestyle change; 47% shared their scp with their primary care provider. |

| 16 | Breast, colorectal; delivered approximately 1 month after completion of active treatment. | Phone survey | 18 Patients | Patients valued the program and suggested the introduction of survivorship during the treatment phase. |

Among the 16 scps analyzed, only 1 had been delivered as part of a randomized controlled trial. That study, by Grunfeld et al.32, found that the only difference between the control group (who received “usual care”) and the intervention group (who received the scp) was that people receiving the scp were more likely to correctly identify their primary care provider as being responsible for their follow-up care. The trial results did not support the authors’ hypothesis that scps are beneficial for improving patient-reported outcomes of people with breast cancer32. However, many researchers, including the authors who designed and implemented the intervention, have suggested a number of alternative explanations and interpretations of the findings32–39. Rather than “signalling the end of scps” (p. 1392)33, the study by Grunfeld and colleagues raises questions that point to the need for additional research.

For 2 scps, the evaluations were particularly extensive and yielded positive reviews from patients and hcps alike. Those plans were the ones designed by livestrong (United States)25,40,41 and the ncsi (United Kingdom)27,29,42, organizations that have been involved in survivorship care planning for longer than most others. As a result, they have been able to conduct repeated evaluations25,27,29,40–49 and to make changes to their scps and delivery processes based on the results of those evaluations.

3.5. A Different Approach

Our analysis revealed that scps, including their method of delivery, have more shared features than differences. One common feature is timing: that is, their development and delivery after treatment. However, one model stands out because of its unique approach and its extensive evaluation27,29,42,49. Undertaken by the ncsi in the United Kingdom5, the plan that we call the ncsi model is not limited to post-treatment, but encompasses the entire cancer trajectory.

Several key features distinguish the ncsi approach. The primary goal is to be “intelligent” about how services are provided by offering care and support to each person in the way that meets the needs of that particular person, rather than by providing a homogenous approach to everyone that is not always effective50. A complementary goal is to support people to engage in self-management to the best of their ability and to offer services accordingly. The extent to which people can engage in self-management is determined through the “holistic assessment and care planning”51 process that begins at diagnosis, continues up to 5 years past active treatment, and takes into consideration all aspects of a person’s life: physical, social, psychological, and spiritual51.

In evaluating their original end-of-treatment approach, the ncsi realized that many of the issues that arose at that time could have been handled earlier in the treatment trajectory50. A clinical nurse-specialist is assigned to each new patient and remains the constant point of contact. In consultation with the care team, that nurse conducts assessments at or near the point of diagnosis, throughout treatment if necessary, and beyond. Those assessments serve as a starting point for discussion and use tools such as the Distress Thermometer and the Sheffield Assessment Instrument51.

As treatment nears completion, the care team stratifies patients into a follow-up care plan based on the level of support they need and the self-management they can achieve—an approach called the “risk stratified pathway”52. At the end of treatment, the multidisciplinary team completes the treatment summary (record of care) and the follow-up care plan. The treatment summary is sent to the primary care provider with a copy to the patient. It is at this point that the ncsi’s approach merges with all the others that we examined, which consider survivorship a distinct phase of care.

This approach is not so much survivorship care as supportive care that begins at diagnosis and culminates in an individualized follow-up plan. The ncsi’s practice of stratifying each patient eliminates the generic one-size-fits-all approach to end-of-treatment survivorship care that has everyone visiting for follow-up appointments at pre-determined times50. The ncsi is convinced that few recurrences are found that way and that that method is ineffective and inefficient for follow-up care53. Multiple evaluations conducted by the ncsi have shown that their broader, personalized approach can lead to improvements in several outcomes, including patient satisfaction54–56, patient confidence in self-managing their own health56, cost effectiveness42,54, and reduced demand for acute care and outpatient resources54,57,58.

4. DISCUSSION

The iom recommendation that scps be provided to patients at completion of treatment has been the impetus behind the creation and implementation of such plans in research and clinical settings in many jurisdictions. However, the recommendation poses a challenge to hcps, because there is little or no consensus on the key features of scps or how to operationalize plan delivery. Previous reviews focused on scps in the United States14,19, but we extended our search to gain a comprehensive view of how scps are used in other parts of the world. Nevertheless, most of the plans identified in our searches came from the United States. Our study indicates many similarities between the approaches used by different institutions. Most scps were used in clinics and provided after treatment at an in-person meeting (in most instances with a nurse), with a copy given to a primary hcp. Despite those similarities, we also uncovered noteworthy features (such as providing scps before the end of active treatment) used by some sites that either adapted the iom recommendations to suit their needs or brought their own interests and evaluation results to bear on their scp design and implementation plan.

The contents of the scps that we examined reflect many of the iom’s recommendations, although the details vary considerably. However, inattention to support services such as psychosocial services and to the identification of a key point of contact and coordinator of continuing care reveal important deviations from the iom’s recommendations and potentially suggest that these services are not components of standard practice in some care settings. The follow-up portions of the scps vary even more in terms of how they follow through with the iom’s recommendations. For example, in our study, only 50% of the scps provide a list of cancer-related information and resources and fewer than 50% address genetic testing or financial concerns. Our findings mirror those of Stricker et al.19, who reviewed breast cancer scps from 13 U.S. centres within the livestrong Survivorship Centres of Excellence Network (livestrong Network), and Salz et al.14, who reviewed breast and colorectal cancer scps from 22 U.S. National Cancer Institute–designated cancer centres in the United States. Those U.S. reviews differ from our own in that they included scps regardless of whether the plans had been evaluated. Nevertheless, as in our review, they observed the same pattern of deviations from the iom’s recommendations.

It appears that many organizations providing scps as part of end-of-treatment survivorship care do not follow all of the current iom recommendations, which raises questions about why they do not14,19,36. Saltz et al.14 argued that one cause of variation in content of scps might be a lack of clarity within the iom framework. In an attempt to start addressing that issue and to refine the essential elements of the framework, the livestrong Foundation in September 2011 convened a meeting that included community leaders, hcps, administrators, people with cancer, and advocates from North America (mostly from the United States). They agreed on a list of 20 essential elements of survivorship care, which included the development and delivery of scps59. After that meeting, the livestrong Foundation and the livestrong Network refined the definitions of those 20 essential elements60, which included defining scps as incorporating a patient-specific treatment summary that includes medical and psychosocial components such as information about treatment, potential long-term and late effects, and potential complications and their signs and symptoms60. Meeting participants also agreed on the need to conduct research evaluating the impact and effectiveness of various models of survivorship care delivery59. We strongly support the latter recommendation. In our study, only half the organizations identified to be using scps and responding to our communication (16 of 33) had evaluation data that they were able to share, and fewer than half of those (just 7) had published their results. In addition, most of the available evaluation data were obtained using non-validated tools and small sample sizes, making it difficult to compare and generalize the results. We argue that identifying or creating reliable instruments to evaluate scps and survivorship programs should be a priority. In addition, most of the evaluation data we analyzed focused on satisfaction and came from patients only. Although a patient focus has huge merit, investigating other outcomes such as distress and quality of life, and involving a broader range of stakeholders such as family members, nurses, oncologists, and administrators might provide a more comprehensive view of survivorship care interventions.

We agree that evaluating survivorship care planning and disseminating findings will assist in determining best approaches, including the essential elements of survivorship care. Many jurisdictions, particularly in North America, have already recognized the value of providing scps to patients. However, we argue that the focus of care planning should not be limited to scps and survivorship at the end of treatment, but should include broader supportive care strategies starting near diagnosis. Most of the North American initiatives we analyzed address survivorship as a distinct phase of care and see scps as tools to be provided to patients at the completion of treatment, as stated by the iom recommendations2. The ncsi’s approach in the United Kingdom expands the understanding of survivorship to cover the entire cancer care continuum, reflecting the important findings from some of the published29,30 and unpublished evaluations of scps included in our review: people want and need information, individualized support, and care planning from diagnosis onward, not just after treatment completion. The ncsi recognizes that assessing the needs that accompany the transition to post-treatment care reveals a number of issues, many of which could be addressed earlier in the trajectory and thus ease the transition process at the time of treatment completion. The ncsi’s care plans are therefore created at or near the time of diagnosis and amended as necessary throughout the cancer care trajectory. That approach to survivorship—or rather, supportive care—by the ncsi puts into practice what others have begun to articulate. Furthermore, their ongoing evaluation through pilot studies and population surveys has resulted in positive findings, demonstrating the success of their approach, independent of cancer group.

We wonder whether, by using the language and concepts of “navigation,”61–65 “case management,”66 or “care coordinator,”67,68 hcps and researchers from many jurisdictions are already trying to address the need for supportive care throughout treatment and beyond. The tools, language, and timing might be different from those used by people speaking in terms of “survivorship” and using scps as defined by livestrong and the iom, but there are features in common. However, these approaches point to a change in thinking about how people can best be supported. For example, the Australian state of Victoria has a statewide Supportive Cancer Care Initiative69 that aims to provide a coordinated approach to supportive care, beginning at diagnosis and continuing throughout the care trajectory—an approach similar to that of the ncsi. Because we used “survivorship” in our search of the literature and practice settings, the Victoria state initiative did not arise in our search.

We propose that, by expanding the scope of survivorship care planning to provide individualized supportive care from the time of diagnosis through the entire cancer care trajectory, cancer care settings might begin to address most of the challenges faced by people living beyond the completion of active treatment and might improve their overall cancer care experience. Used within the context of this broader approach to supportive care, care plans can be a powerful support tool for people during their cancer care trajectory. We caution, however, that care plans must be considered not as standalone documents, but as tools that are part of a larger holistic care-planning approach. That holistic approach to supportive care planning not only attends to the original goals of the iom’s recommendations—to facilitate the transition to the next stage of life and to ensure that people receive the appropriate follow-up care in a timely manner2—but also expands on the recommendations to improve the experience of cancer care from the beginning.

5. FUTURE RESEARCH

The parameters of our study limited the scope of our findings, which draw attention to future research possibilities. It is possible that our search strategy has not identified scps from all English-speaking countries. In addition, expanding the analysis to include supportive care initiatives in non-English speaking jurisdictions could potentially yield interesting results. As organizations engage in strategies beyond the iom recommendations (for example, the ncsi model), the limitations inherent in conceptualizing survivorship as a distinct phase of care could be challenged, providing opportunities for further research. When we completed our study in April 2012, many organizations with whom we had communicated were in the process of evaluation and publication of their findings. As those publications become available, they will expand the current literature base on both survivorship and supportive care beyond what has been described here. We look forward to seeing published research that examines the implementation not only of the iom framework, but also of strategies that move beyond it.

6. SUMMARY

In early 2012, we conducted a review of English-language scps that had been evaluated, including those used on different continents in both research and clinical settings. The approaches to delivery and the extent to which the documents followed the original recommendations from the iom varied considerably. However, more research that evaluates and compares the effectiveness of these different approaches is needed. In most settings, survivorship is considered a distinct phase at the end of treatment, and scps are documents created and delivered after primary treatment is complete. Our findings point to an approach to care that goes beyond the iom recommendations, incorporating assessments and care planning from the point of diagnosis to beyond treatment. A holistic assessment and planning process for supportive care that is not limited to the treatment of illness, but that appreciates the need for physical, psychological, social, and spiritual care for people with cancer and their families will allow for levels of support and care appropriate to each person. The result can be improved quality of life for people affected by cancer.

7. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the clinicians and researchers who kindly shared documents and information about survivor-ship care planning at their organizations. In particular, we are grateful to Noeline Young of the National Cancer Survivorship Initiative for her time and communication regarding supportive care in the United Kingdom. We also acknowledge Dr. Amanda Ward for her participation in data collection and analysis. This research was funded by the BC Cancer Agency Provincial Survivorship Program.

8. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

9. REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt ME, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuben SH. Living Beyond Cancer: Finding a New Balance: President’s Cancer Panel 2003–2004 Annual Report. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2012. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macmillan Cancer Support. National Cancer Survivorship Initiative [Web page] London, U.K.: Macmillan Cancer Support; 2012. [Available at: http://www.ncsi.org.uk/; cited October 5, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Statistics Canada. Home > Publications > 82-226-X > Cancer Survival Statistics [Web page] Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2012. [Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-226-x/2012001/aftertoc-aprestdm2-eng.htm; cited October 5, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Research UK. Home > News & Resources > CancerStats > Key Facts > All cancers combined [Web page] London, U.K.: Cancer Research UK; 2012. [Current version available at: http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/keyfacts/Allcancerscombined; cited October 5, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cancer survivors—United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:269–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, Harvey C. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2270–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantsiper M, McDonald EL, Geller G, Shockney L, Snyder C, Wolff AC. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):S459–66. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson EK, Sugden EM, Rose PW. Views of primary care physicians and oncologists on cancer follow-up initiatives in primary care: an online survey. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:159–66. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0117-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nissen MJ, Beran MS, Lee MW, Mehta SR, Pine DA, Swenson KK. Views of primary care providers on follow-up care of cancer patients. Fam Med. 2007;39:477–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faul LA, Shibata D, Townsend I, Jacobsen PB. Improving survivorship care for patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Control. 2010;1:35–43. doi: 10.1177/107327481001700105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salz T, Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS, Layne TM, Bach PB. Survivorship care plans in research and practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:101–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Achieving Best Practice Cancer Care: A Guide for Implementing Multidisciplinary Care. Melbourne, Australia: Metropolitan Health and Aged Care Services Division, Victorian Government Department of Human Services; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Follow-Up in Oncology: Identify Objectives, Substantiate Actions. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands; 2007. [Available online at: http://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/en/publications/healthcare/follow-oncology-identify-objectives-substantiate-actions; cited July 17, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vachani C, Di Lullo GA, Hampshire MK, Hill–Kayser CE, Metz JM. Preparing patients for life after cancer treatment: an online tool for developing survivorship care plans. Am J Nurs. 2011;111:51–5. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000396557.24867.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baravelli C, Krishnasamy M, Pezaro C, et al. The views of bowel cancer survivors and health care professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow up. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stricker CT, Jacobs LA, Risendal B, et al. Survivorship care planning after the Institute of Medicine recommendations: how are we faring? J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:358–70. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn EE, Ganz PA. Survivorship programs and care plans in practice: variations on a theme. J Oncol Practice. 2011;7:70–5. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (nci) Facing Forward: Life After Cancer Treatment. Bethesda, MD: NCI; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canadian Cancer Society. Life After Cancer: A Guide for Cancer Survivors. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cancer Council Australia. Living Well After Cancer: A Guide for Cancer Survivors, Their Family and Friends. Surry Hills, Australia: Cancer Council Australia; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill–Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, Jacobs LA, Metz JM. An Internet tool for creation of cancer survivorship care plans for survivors and health care providers: design, implementation, use and user satisfaction. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e39. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shalom MM, Hahn EE, Casillas J, Ganz PA. Do survivor-ship care plans make a difference? A primary care provider perspective. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:314–18. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pye K, on behalf of the U.K. Views of Health Professionals and Users of the Treatment Summary and Care Plan Surveys. London, U.K: Macmillan Cancer Support; 2011. National Cancer Survivorship Initiative Evaluation Project Team. [Available online at: http://system.improvement.nhs.uk/ImprovementSystem/ViewDocument.aspx?path=Cancer/National/National%20Project/CYP%20Pathway%20documents/TS-CP_final_report_Sept_2011.pdf; cited December 20, 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trotter K, Frazier A, Hendricks CK, Scarsella H. Innovation in survivor care: group visits. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:E24–33. doi: 10.1188/11.CJON.E24-E33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkinson A, for NHS Improvement . National Cancer Survivorship Initiative (ncsi) Assessment and Care Planning. London, U.K.: Department of Health, NHS Improvement; 2010. [Available online at: http://www.ncsi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Summary-of-the-ACP-Evaluation-Report.pdf; cited December 20, 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hausman J, Ganz PA, Sellers TP, Rosenquist J. Journey forward: the new face of cancer survivorship care. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(suppl):e50s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayer D, Gerstel A, Leak AN, Smith SK. Patient and provider preferences for survivorship care plans. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e80–6. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, et al. Evaluating survivorship care plans: results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4755–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jefford M, Schofield P, Emery J. Improving survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1391–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.5886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stricker CT, Jacobs LA, Palmer SC. Survivorship care plans: an argument for evidence over common sense. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1392–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Maunsell E, Pond G, Coyle D, Levine MN. Reply to M. Jefford et al. and C.T. Stricker et al. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1393–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.6892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Earle CC, Ganz PA. Cancer survivorship care: don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3764–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith TJ, Snyder C. Is it time for (survivorship care) plan B? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4740–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith TJ, Snyder C. Reply to C.T. Stricker et al. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1394–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jefford M, Schofield P, Emery J. Improving survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1391–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.5886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill–Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, Jacobs LA, Metz JM. Survivorship care among cancer patients having undergone radiotherapy: the utilization of Internet-based survivorship care plans [abstract 1057] Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(suppl):S138–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.06.455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill–Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, Metz JM. High level use and satisfaction with Internet-based breast cancer survivorship care plans. Breast J. 2012;18:97–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Measuring Cost and Impact. York, U.K: University of York, Health Economic Consortium; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill–Kayser CE, Hampshire MK, Metz JM. Use of Internet-based survivorship care plan by survivors of head and neck cancer [abstract 2460] Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(suppl):S388. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hill–Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, Di Lullo GA, Metz JM. The role of Internet-based cancer survivorship care plans in care of the elderly. J Geriatr Oncol. 2011;2:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2010.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hill–Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, Metz JM. Worldwide use of Internet-based survivorship care plans. Eur Oncol. 2010;6:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hill–Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, Jacobs LA, Metz JM. Adolescent and young adult use of Internet-based cancer survivorship care plans [abstract 9117] J Clin Oncol. 2010;28 [Available online at: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/54007-74; cited April 12, 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hill–Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, Jacobs LA, Metz JM. Utilization of Internet-based survivorship care plans by lung cancer survivors. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10:347–52. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill–Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, Jacobs LA, Metz JM. Utilization of Internet-based survivorship care plans by survivors of gynecologic cancers [abstract 5592] J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.047. [Available online at: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/35725-65; cited April 12, 2014] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maher EJ. Managing the consequences of cancer treatment and the English National Cancer Survivorship Initiative. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:225–32. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.746467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.NHS Improvement . Effective Follow-Up: Testing Risk Stratified Pathways. Leicester, U.K.: NHS Improvement; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51.U.K. National Cancer Action Team (ncat) Holistic Needs Assessment for People with Cancer: A Practical Guide for Healthcare Professionals. London, U.K: Macmillan Cancer Support; 2011. [Available online at: http://www.ncsi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/The_holistic_needs_assessment_for_people_with_cancer_A_practical_Guide_NCAT.pdf; cited October 5, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 52.NHS Improvement . Stratified Pathways of Care...From Concept to Innovation: Executive Summary. Leicester, U.K.: NHS Improvement; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fenlon D, Foster R, on behalf of the Macmillan Survivorship Research Group . Care After Cancer. London, U.K.: Macmillan Cancer Support; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davies NJ, Batehup L. Towards a personalised approach to aftercare: a review of cancer follow-up in the UK. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:142–51. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Cancer Survivorship Initiative. Adult Survivorship: From Concept to Innovation. London, U.K: Macmillan Cancer Support; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evaluation of Adult Cancer After Care Services: Quantitative and Qualitative Service Evaluation for NHS Improvement [slide presentation] London, U.K.: Ipsos MORI; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carlowe J. Self management. A little help from yourself. Health Serv J. 2010;120(suppl 6–7) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharing the Learning Through Posters; the Work of the National Cancer Survivorship Initiative (NCSI) test sites, supported by NHS Improvement (2012) London, U.K.: NHS Improvement; 2012. [Available online at: http://www.ncsi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Sharing_the_learning_through_posters_March_2012.pdf; cited October 5, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 59.The Essential Elements of Survivorship Care: A LIVESTRONG Brief. Austin, TX: LIVESTRONG Foundation; 2011. [Available online at: https://assets-livestrong-org.s3.amazonaws.com/media/site_proxy/data/7e26de7ddcd2b7ace899e75f842e50c0075c4330.pdf; cited October 5, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 60.The LIVESTRONG Essential Elements of Survivorship Care: Definitions and Recommendations. Austin, TX: LIVESTRONG Foundation; 2011. [Available online at: https://assets-livestrongorg.s3.amazonaws.com/media/site_proxy/data/6f57b05726c2db3f56a85a5bd8f5dad166b80b92.pdf; cited October 5, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carroll JK, Humiston SG, Meldrum SC, et al. Patients’ experiences with navigation for cancer care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:241–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fillion L, Cook S, Veillette AM, et al. Professional navigation framework: elaboration and validation in a Canadian context. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:E58–69. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E58-E69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Case MA. Oncology nurse navigator. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:33–40. doi: 10.1188/11.CJON.33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:237–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Braun KL, Kagawa–Singer M, Holden AE, et al. Cancer patient navigator tasks across the cancer care continuum. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:398–413. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wulff CN, Thygesen M, Sondergaard J, Vedsted P. Case management used to optimize cancer care pathways: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:227. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Walsh MC. Survivorship Care Plans: Exploring Lymphoma Patients’ Knowledge of Their Disease and Follow-Up. Boston, MA: Simmons College; 2011. [Doctor of Nursing Practice dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Evaluation of the Role of Cancer Care Coordinator: Summary Report. Eveleigh, Australia: Cancer Institute NSW; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Supportive Care Needs of People with Cancer and Their Families: A Model for Supportive Care Provision in Victoria. Melbourne, Australia: Department of Health, Cancer Strategy and Development; 2006. [Google Scholar]