Abstract

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumours (pecomas) are rare mesenchymal tumours. Some have a benign course; others metastasize. Treatment of malignant pecomas is challenging, and little is known about treatment for patients with metastatic disease. Here, we report a case of metastatic malignant pecoma with estrogen and progesterone receptor expression that showed a favourable and sustained response to letrozole.

Keywords: Malignant pecoma, pecoma, receptors, estrogen, progesterone, metastasis, letrozole, sirolimus

1. INTRODUCTION

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumours (pecomas) are a group of rare mesenchymal neoplasms with a spectrum of clinical disease ranging from indolent to aggressive (“malignant pecoma”). There is a dearth of treatment options in advanced disease. Standard anthracycline- and gemcitabine-based chemotherapy regimens have yielded limited clinical activity. Inhibition of mtor (the mammalian target of rapamycin) has recently emerged as a new treatment strategy in malignant pecoma1,2. Here, we present a case of metastatic malignant pecoma with estrogen and progesterone receptor expression that showed a favourable and sustained response to letrozole.

2. CASE DESCRIPTION

In March 2007, a 54-year-old woman underwent re-section of a large retroperitoneal malignant pecoma measuring 18×10×9 cm [Figure 1(A,B)]. A metastatic work-up, including thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography imaging revealed 4 bilateral progressively enlarging lung nodules (largest: 1.8×1.7 cm).

FIGURE 1.

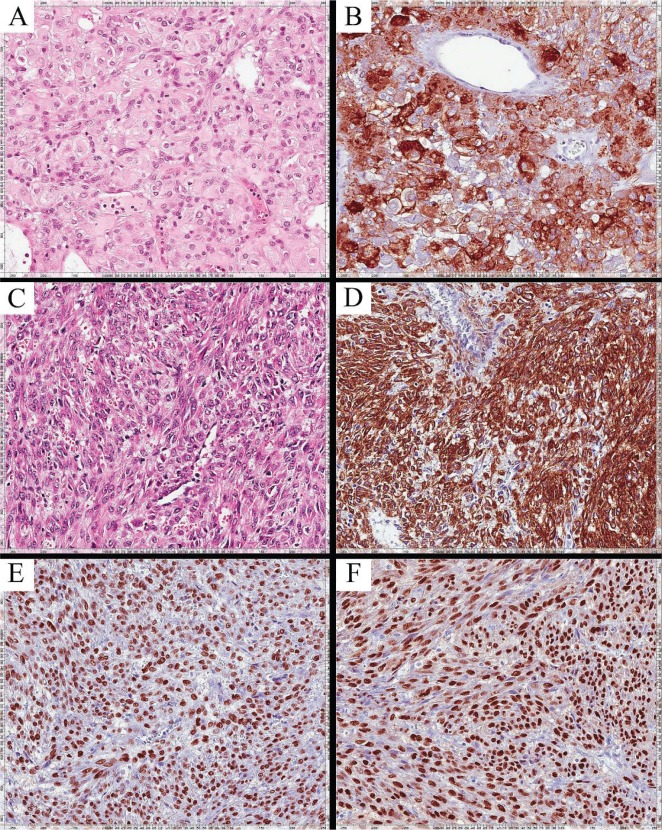

Histologic appearance of the perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections). The original abdominal specimen obtained in 2007 is stained with (A) hematoxylin and eosin, and (B) actin (20× original magnification). Specimens of the lung nodules resected in 2008, stained with (C) hematoxylin and eosin, and (D) actin (20× original magnification), appear morphologically similar to the original tumour. Subsequent staining of the lung nodule specimens with (E) anti–estrogen receptor and (F) anti–progesterone receptor antibody showing more than 90% expression of those receptors.

In November 2008, the patient underwent a wedge resection to remove the 3 largest pulmonary nodules. Pathology examination of the lung nodules [Figure 1(C,D)] confirmed a metastatic sarcomatous tumour morphologically similar to the previously diagnosed intra-abdominal pecoma.

The patient was followed with serial imaging. In December 2010, computed tomography revealed progressive lung nodules, new axillary and retroperitoneal nodes, and an enlarging soft-tissue mass arising in the left chest wall and the left hemi-abdomen.

Between January and October 2011, the patient received palliative radiotherapy to the left chest wall soft-tissue mass with limited clinical benefit, followed by 6 cycles of liposomal doxorubicin, with an end result of disease progression. A brief period of disease stabilization from January 2012 to June 2012 was achieved with the mtor inhibitor sirolimus 4 mg daily, but disease progression soon followed, and sirolimus was discontinued.

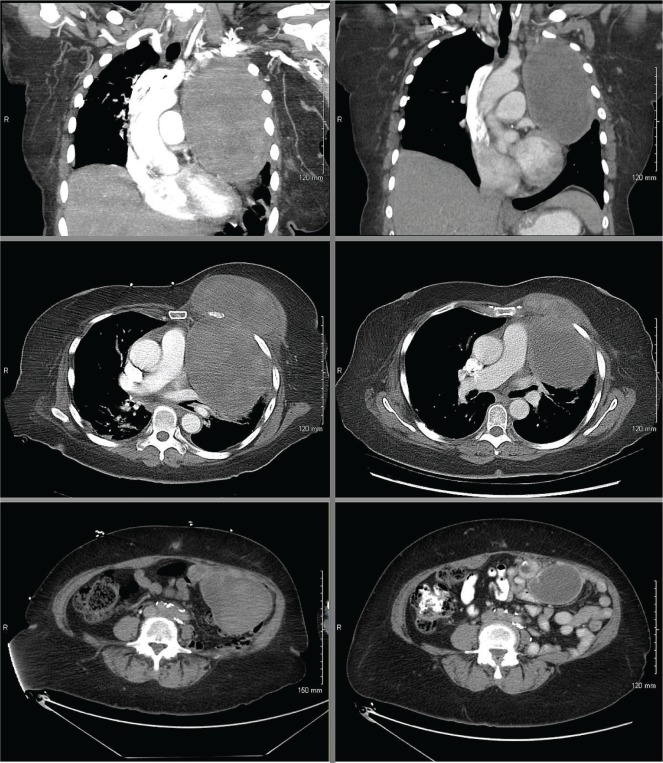

Immunohistochemical examination of the original abdominal surgical specimen and the subsequently resected lung nodules showed that more than 90% of the tumour cells stained moderately-to-strongly positive for the estrogen and progesterone receptors [Figure 1(E,F)]. Letrozole 2.5 mg daily was initiated in August 2012 at a time when the patient’s condition had deteriorated, with the need for supplemental oxygen because of bulky intrathoracic disease with associated atelectasis. A clinical and radiologic partial response was noted by 12 weeks of treatment (Figure 2), and the need for supplemental oxygen ceased. Sixteen months after treatment initiation, the patient continued to derive clinical benefit from letrozole treatment.

FIGURE 2.

Objective response of a malignant metastatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumour to letrozole (left panels, before treatment; right panels, after treatment). (Upper panels) Sagittal computed tomography (ct) views of the sternal mass, showing a size decrease to 12.2×7.5×12 cm from 16×11×16.6 cm. (Middle panels) Axial ct views of the sternal mass. (Bottom panels) Axial ct views of the mesenteric mass, showing a size decrease to 5.2×6.9 cm from 12×6.7 cm. The smaller lesions at the other sites of metastatic disease were similarly stable or smaller in size.

3. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The pecoma family of tumours comprises angiomyolipoma of the kidney, clear cell sugar tumour, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (lam) of the lung, and also perivascular epithelioid cell tumour not otherwise specified (pecoma-nos), which are pecoma tumours arising in non-classical anatomic locations. In contrast to renal angiomyolipoma and pulmonary lam, which are generally considered benign tumours, some pecoma tumours can exhibit frank malignant potential with an unpredictable clinical course3.

Other tumours of the pecoma family, such as renal angiomyolipoma4 and pulmonary lam5, show evidence of increased estrogen receptor, androgen receptor, and aromatase expression; however, the presence of hormone receptor expression in pecomas is not well reported in the literature. For example, in a large case series, estrogen and progesterone receptor testing was performed in only 3 of the 26 reported cases, and results were negative in all 3 cases6. Although the prevalence of estrogen receptors in pecoma is largely undefined, the female predominance of the disease3 suggests that hormone receptors might also be present in some pecomas. Furthermore, the common expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in renal angiomyolipoma and pulmonary lam, which share morphologic similarities with pecomas, suggest that this hormone pathway is a plausible target that should be pursued further in cases of malignant pecoma.

In pulmonary lam, several reports have described the successful use of hormone manipulation with a variety of modalities such as tamoxifen, oophorectomy, or luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone analogs7–12. However, this therapeutic approach has not been widely reported or attempted in cases of pecoma. In fact, only a single case report has detailed the use of hormone manipulation in the management of malignant pecoma in the adjuvant setting, where response could not be documented13.

The role of estrogen in pecomas is unclear. The original association of estrogen in the pathogenesis of pulmonary lam was inferred based largely on the characteristics of the affected patients (namely, women of reproductive age); however, the mechanism by which estrogen is involved in the development of the disease remains uncertain to this day. Recently, an association has been identified between pecomas and tuberous sclerosis14, an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by an inactivating mutation of a tumour suppressor gene, TSC1 or TSC2. In mice with tuberin (Tsc2)–null xenograft tumours, estrogen has been shown to increase the rates of pulmonary metastases and circulating tumour cells through activation of mek-dependent pathways15. In humans, estrogen might, through a similar mechanism, stimulate pecoma tumour cells because of a mutation in the TSC2 tumour suppressor gene. Blocking estrogen might therefore inactivate the mek pathway and provide a rationale for therapeutic efficacy. Aromatase inhibitors such as letrozole bind to aromatase, an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of androgen to estrogen, effectively depleting circulating levels of estrogen in the body.

The dramatic response of our patient to letrozole suggests that patients with hormone-rich malignant pecomas might benefit from similar therapy.

4. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

5. REFERENCES

- 1.Italiano A, Delcambre C, Hostein I, et al. Treatment with the mtor inhibitor temsirolimus in patients with malignant pecoma. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1135–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stacchiotti S, Marrari A, Dei Tos AP, Casali PG. Targeted therapies in rare sarcomas: imt, asps, sft, pecoma, and ccs. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27:1049–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleeker JS, Quevedo JF, Folpe AL. “Malignant” perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm: risk stratification and treatment strategies. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:541626. doi: 10.1155/2012/541626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boorjian SA, Sheinin Y, Crispen PL, Lohse CM, Kwon ED, Leibovich BC. Hormone receptor expression in renal angiomyolipoma: clinicopathologic correlation. Urology. 2008;72:927–32. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.01.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger U, Khaghani A, Pomerance A, Yacoub MH, Coombes RC. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis and steroid receptors. An immunocytochemical study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93:609–14. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/93.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C, Balzer BL, Weiss SW. Perivascular epitheloid cell neoplasm of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1558–75. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173232.22117.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi GA, Balbi B, Oddera S, Lantero S, Ravazzoni C. Response to treatment with an analog of the luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone in a patient with pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:174–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliasson AH, Phillips YY, Tenholder MF. Treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. A meta-analysis. Chest. 1989;96:1352–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.6.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urban T, Kuttenn F, Gompel A, Marsac J, Lacronique J. Pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis. Follow-up and long-term outcome with antiestrogen therapy; a report of eight cases. Chest. 1992;102:472–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.2.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banner AS, Carrington CB, Emory WB, et al. Efficacy of oophorectomy in lymphangioleiomyomatosis and benign metastasizing leiomyoma. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:204–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198107233050406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiavina M, Contini P, Fabiani A, et al. Efficacy of hormonal manipulation in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. A 20-year-experience in 36 patients. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2007;24:39–50. doi: 10.1007/s11083-007-9058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casanova A, Ancochea J. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: new therapeutic approaches [Spanish] Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:579–80. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosincu L, Rocca PC, Martignoni G, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell (pec) tumors of the uterus: a clinicopathologic study of two cases with aggressive features. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1336–42. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1345–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu JJ, Robb VA, Morrison TA, et al. Estrogen promotes the survival and pulmonary metastasis of tuberin-null cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2635–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810790106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]