Abstract

The circadian system organizes sleep and wake through imposing a daily cycle of sleep propensity on the organism. Sleep has been shown to play an important role in learning and memory. Apart from the daily cycle of sleep propensity, however, direct effects of the circadian system on learning and memory also have been well documented. Many mechanistic components of the memory consolidation process ranging from the molecular to the systems level have been identified and studied. The question that remains is how do these various processes and components work together to produce cycles of increased and decreased learning abilities, and why should there be times of day when neural plasticity appears to be restricted? Insights into this complex problem can be gained through investigations of the learning disabilities caused by circadian disruption in Siberian hamsters and by aneuploidy in Down syndrome mice. A simple working hypothesis that has been explored in this work is that the observed learning disabilities are due to an altered excitation/inhibition balance in the CNS. Excessive inhibition is the suspected cause of deficits in memory consolidation. In this paper we present the evidence that excessive inhibition in these cases of learning disability involves GABAergic neurotransmission, that treatment with GABA receptor inhibitors can reverse the learning disability, and that the efficacy of the treatment is time sensitive coincident with the major daily sleep phase, and that it depends on sleep. The evidence we present leads us to hypothesize that a function of the circadian system is to reduce neuroplasticity during the daily sleep phase when processes of memory consolidation are taking place.

Keywords: Down syndrome, GABA, Siberian hamster, mouse, learning, memory, pentylenetetrazole, novel object recognition

Introduction

Many hypotheses about possible functions of sleep and sleep states have been advanced over the years (eg. Crick and Mitchison 1983, Horne 1988, McGinty and Szymusiak 1990, Wehr 1992, Krueger and Obal 1993, Benington and Heller 1995, Jouvet 1998, Tononi and Cirelli 2003), but a subset of those hypotheses that focus on neural plasticity, and more specifically on learning and memory has grown and gained support in recent years (eg. Frank et al. 2001, Maquet 2001, Walker and Stickgold 2004, Stickgold 2005). Early evidence mostly came from experiments in which sleep deprivation was shown to impair both declarative and procedural memories, and therefore these results could have been due to indirect and non-specific effects of sleep deprivation on the performance of subjects during retesting. However, continuing work pointed to specific functions of sleep in the processes of neural plasticity and of memory consolidation. Frank et al. (2001) showed that synaptic remodeling in the visual cortices of kittens subjected to monocular deprivation depended on sleep. Experiments on humans showed that when subjects were sleep deprived for a night following training in a perceptual skill task, but not tested until after two nights of recovery sleep, they showed no benefit from the training (Stickgold et al. 2000). In comparison, subjects allowed to sleep after task training showed large performance improvements the following day, and they continued to improve with subsequent nights of sleep. The interpretation was that sleep within the same daily cycle following the training is essential for optimal memory consolidation. Another study on human perceptual skill training avoided sleep deprivation by examining the effect of a daytime nap on acquisition of a perceptual skill and showed performance benefits equivalent to those seen after a night of sleep (Mednick et al. 2003). These experiments and many others lead to the conclusion that sleep plays important roles in memory consolidation, and sleep deprivation interferes with those processes.

A direct relationship between sleep and procedural memory was elegantly shown by Huber et al. (2004) in experiments in which subjects were trained to use a computer mouse to move the cursor to a target on the computer screen. EEG recordings during subsequent sleep showed alterations in the quality of sleep specifically in the region of the motor cortex that was engaged by the training. The feature of sleep that was altered was the amount of slow wave activity (.5 – 4.5 Hz) in the EEG occurring during NREM sleep. This band of EEG oscillations is called the delta band, and when quantified through Fourier analysis is referred to as delta power. Furthermore, the performance improvement of the subjects following sleep was directly related to the measured increase in delta power. Thus, for a specific region of the brain, a clear relationship was established between an electrophysiological feature of sleep and improved performance in a motor-skill learning task. The relationship between sleep and performance was also demonstrated in a study that manipulated EEG slow wave activity during sleep using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Inducing 0.75 Hz oscillations with TMS during early nocturnal NREM sleep enhanced the retention of hippocampal-dependent declarative memories in normal subjects (Marshall et al. 2006).

Electrophysiological studies of rodents are exploring the brain mechanisms involved in memory coding during wake and memory consolidation during sleep. Simultaneous recordings of many hippocampal neurons during maze running reveal activity patterns that correlate with locations in the maze. These patterns are seen to replay during quiet wakefulness and also during sleep (Wilson and McNaughton 1994, Lee and Wilson 2002), and during sleep they seem to be relayed to the cortex in association with specific local field potentials (Siapas and Wilson 1998, Siapas et al 2005, Jones and Wilson 2005, Ji and Wilson 2007, Ramadan et al 2009, Carr et al, 2011). The insights gained from these and many more animal studies along with fMRI studies in humans have been synthesized into a hypothesis of how memory consolidation occurs during sleep (Born and Wilhelm 2012). Thus, the concept that sleep plays an essential role in learning and memory is on very solid ground. But, what role might be played by circadian rhythms?

The obvious connection between circadian rhythms and learning/memory is the influence of the circadian system on sleep. A circadian rhythm of alertness and sleep permissiveness interacting with a wake dependent accumulation of sleep-need assures the maintenance of a daily sleep/activity pattern that corresponds to the daily light/dark cycle in both humans and animals (Borbely and Achermann 1992). Two potential consequences for learning and memory experiments derive from the circadian control of sleep: (1) training during the circadian rest phase could result in sleep deprivation that would impact learning and memory, or (2) lower levels of alertness during the rest phase could detract from the ability to form memories when training occurs at this phase of the daily cycle. Of course an additional possibility is that a factor with a circadian rhythm such as hormone release or gene expression is having an effect on learning and memory apart from sleep.

Experiments on humans and animals do not support the concept that memory impairment due to sleep deprivation caused by training is a critical variable in studies of daily cycles of learning and memory performance. When humans are placed on a forced desynchrony protocol in which the circadian rhythm of body temperature does not remain in phase with sleep timing, the performance on memory and cognitive tasks follows the circadian rhythm of body temperature and not the sleep cycle (Johnson et al. 1992). When animals are trained and tested at different times around the daily cycle of rest and activity, memory is seen to have a locked phase relationship with time of training meaning that learning is just as effective when training occurs during the normal sleep phase or the normal active phase (Holloway and Wansley 1973). And finally, studies of long-term potentiation (LTP) on hippocampal slices reflect daily cycles of magnitude in the absence of sleep deprivation prior to animal sacrifice (Chaudhury et al. 2005). It may be concluded, therefore, that the mammalian brain undergoes a daily cycle of ability to acquire and consolidate memories, or in other words, a daily cycle of neural plasticity.

One view of the daily cycle of learning and memory propensity is that it is due to mechanisms promoting higher levels of alertness during the daily active phase. In this paper we advance the alternative view that the daily cycles of low learning and memory consolidation ability are due to active suppression of neural plasticity during the daily rest phase. We propose that the mechanism of this suppression is GABAergic, and we show that abnormally high levels of this GABAergic inhibition can be the cause of at least one case of learning disability – Down syndrome. We review experiments on Siberian hamsters that indicate that the possible origin of the GABAergic suppression of neural plasticity is the circadian pacemaker, the suprachiasmatic nucleus. We conclude by advancing the hypothesis that: (1) there is an adaptive function of the daily phases of suppression of neural plasticity, and (2) that function is to protect the integrity of memory traces during the processes of memory consolidation that occur during sleep. We recognize that aspects of memory consolidation occur during wake resulting in what has been referred to as intermediate-term memory that lasts for minutes to hours. In this paper, however, we are focusing on the processes that result in durable long-term memory that lasts from days to lifetimes.

Learning ability in DS model mice can be rescued with GABA antagonists

Down syndrome (DS) in humans results from trisomy of chromosome 21 which contains an estimated 250 genes making DS a complex disease associated with many disorders. One feature of Down syndrome that seriously compromises quality of life for individuals and families is intellectual disability. Because the incidence of DS is around 1 in 700 births, it is the leading genetic cause of learning disability. Many symptoms of DS such as hearing and vision disorders, thyroid and heart disorders, cancer, and gastrointestinal disorders can be medically treated resulting in increased longevity, but no treatments exist for the intellectual disability. Excellent mouse models of DS have been generated through genetic engineering that has produced mice that are aneuploid for genes syntenic to those on human chromosome 21. The Ts65Dn mouse is trisomic for about 150 syntenic genes and shows many features of human DS including severe learning disabilities as revealed by traditional rodent learning tasks (Reeves et al. 1995).

In vitro studies of hippocampal neurons in brain slices indicated the possible involvement of inhibition in memory deficits in Ts65Dn mice. Abnormalities in long-term potentiation (LTP) were observed in these preparations and were shown to involve excessive GABAergic inhibition (Kleschevnikov et_al., 2004; Costa and Grybko, 2005). Fabian Fernandez working with Craig Garner at Stanford University first tested the possibility that overinhibition was responsible for learning disability in behaving Ts65Dn mice. Three different GABAA receptor antagonists, picrotoxin (PTX), pentylenetetrazole (PTZ), and bilobilide, were shown to normalize learning and memory in the Ts65Dn mice as assessed through the novel object recognition task for long-term memory and the T-maze spontaneous alternation task for working memory (Fernandez et al. 2007). In addition, this study also evaluated hippocampal LTP in Ts65Dn mice, and found it to be greatly reduced in comparison to 2N littermates. Treatment with PTZ rescued LTP in the Ts65Dn mice. A remarkable result of the Fernandez et al. study was that the drug treatments were delivered daily for 2 weeks, but the cognitive and LTP benefits were observed one week to 1 month later, long after the drugs had cleared the system. Thus, a short-term chronic drug treatment resulted in long-term changes in neuroplasticity.

In recognition of the known involvements of circadian rhythms and sleep in learning and memory, Ruby et al. (2010) investigated whether there were any circadian abnormalities in Ts65Dn mice. The findings were that the circadian rhythms of the Ts65Dn mice were perfectly intact, and in fact had higher periodogram scores than seen in the 2N littermates. The significance of these apparent negative results were not appreciated at the time, but may reflect the over-inhibition mechanism.

Sleep analysis of the Ts65Dn mice, revealed some differences between the DS and 2N mice (Colas et al. 2008, and unpublished results). The DS mice have higher EEG spectral power across all frequencies. The DS mice have a delayed sleep onset at the beginning of the dark phase, reduced NREM sleep delta power, increased theta power in both REM and NREM sleep, decreased NREM sleep during the dark phase, increased REM sleep during the light phase, and an increased theta/delta ratio across the board. PTZ treatment did not affect sleep amounts, but it did lower spectral power and the theta/delta ratio. These results do not reveal an obvious sleep abnormality that would seem to explain the inability of these animals to form long-term memories, but studies in which sleep of the DS mice was altered indicate that sleep has a role in the efficacy of the PTZ treatment as well as a role in learning and memory in non-drug treated DS mice. First, if the DS mice were sleep deprived for 1.5 hrs following each dose of PTZ (given during the light phase), the drug had no effect. Thus, sleep was required for the GABAA antagonist to affect neuroplasticity. Second, independent of PTZ treatment, non-drug induced sleep enhancement had a strong pro-cognitive effect. Sleep enhancement was produced by sleep depriving the DS mice for 4 hrs. prior to their training on the novel object recognition (NOR) task (Figure 1A). Following the training, the mice were allowed to sleep ad lib. until testing 24 hrs later. Over that time their delta power was normalized. During testing 24 hr after training, their NOR task performance was not different from that of 2N mice (Figure 1B, Colas et al. unpublished data). These results suggest that a sleep related factor in the DS mice is involved in their learning and memory impairment

Figure 1.

Sleep intensification following sleep deprivation improves novel object recognition memory in Ts65Dn mice. The protocol for this experiment is shown in panel A. Mice were trained early in the second half of the light phase and were tested 24 hrs. later. One cohort of mice was sleep deprived by gentle handling for 4 hrs. prior to training. Panel B shows the NOR performance in 2N and Ts65Dn mice that were not sleep deprived (baseline) and that were sleep deprived prior to training (SD). Unpublished data from Colas et al. presented as means +/− SEM. ** indicates P<.01 based on t-test for paired samples.

The efficacy of the PTZ treatment is not only dependent on sleep, but it is also dependent on circadian phase. In experiments by Fernandez et al. (2007) and subsequent studies (Colas et al. 2013)(Figure 2A), the PTZ was administered during the light phase of the daily cycle, which for mice is the rest/sleep phase (Figure 2B). When the timing of the PTZ administration was shifted 180° to the dark or active phase, it had no effect (Figure 2C). The implication of these results is that excessive GABAergic inhibition in the DS mice was occurring during the light/sleep phase, and its impact was on some process that required sleep. Furthermore, since the activity of the circadian pacemaker, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is highest during the light phase (Schwartz et al. 1983), the question arises -- could the SCN be the source of the excess GABA signaling in the DS mice? Also, could the observation of the stronger activity rhythms observed in DS mice (Ruby et al. 2010), reflect higher SCN activity and therefore greater GABA output from the SCN during the light phase in these mice?

Figure 2.

PTZ improves novel object recognition memory in Ts65Dn mice only if the animals are dosed during the light phase of the daily cycle. A. Treatment protocol was 2 weeks of daily ip injections of PTZ at 0.3 mg/kg or of saline. At least 1 week was allowed between end of treatment and testing. B. NOR test results for 2–3 month old mice treated with PTZ (0.3 mg/kg) or saline. Two objects were used, and discrimination index is the time spent with the novel object divided by time spent with novel and familiar objects. Gray bars are training and black bars are novel recognition results 24 hrs. later. C. NOR test results from mice receiving PTZ treatment (0.3 mg/kg) or saline during the dark phase. Data from Colas et al. 2013 presented as means +/− SEM. * indicates P<.05,** indicates P<.01 based on t-test for paired samples.

Learning ability in arrhythmic Siberian hamsters can be rescued by a GABA antagonist

Previous studies of learning and memory in rats and mice showed strong circadian modulation (McGaugh 1966; Holloway and Wansley 1973a, b; Stephan and Kovacevic 1978; Chaudhury and Colwell 2002; Cain et al. 2004). However, learning and memory in rats was not impaired when they were rendered arrhythmic by lesions of the SCN. In fact, they appeared to learn better in that their performance measured at various times was not different from their best performances (Stephan and Kovacevic 1978, Mistlberger et al., 1996). In other words, the arrhythmia eliminated daily nadirs in performance scores. New insights into the role of the circadian system were made possible by the development of a new model of circadian arrhythmia in the Siberian hamster (Ruby et al. 1996). This model is unique because it does not involve an invasive, genetic, or pharmacological manipulation; it only involves a single exposure to an extra 2 hours of light late at night followed by a 3-hour delay in the onset of the dark phase on the next day. This combination of phase-advancing and phase-delaying light signals has been termed a circadian disruptive phase shift (DPS) by Prendergast et al. (2012). The majority of Siberian hamsters respond to the DPS by becoming circadian-arrhythmic for the rest of their natural lives even though they continue to live under a 24-hr light-dark cycle. Due to the fact that the DPS treatment does not involve brain damage (lesion) or a genetic alteration (eg. gene knock out) that could have developmental or other effects, it was seen as an ideal model for asking questions about the functional significance of circadian rhythms including their role in learning and memory.

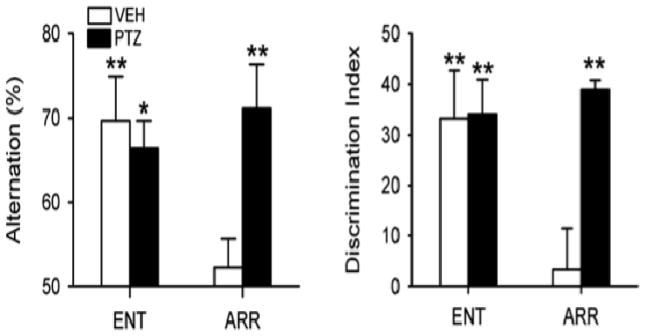

In contrast to the earlier results on SCN lesioned, arrhythmic rats, the hamsters made arrhythmic by the DPS were severely learning disabled. Whereas they performed normally in the NOR test when the training to testing interval was 20 min or less, they were unable to form long-term memories of objects if the training to testing interval was 60 min or 24 hr (Ruby et al. 2008). Spatial working memory also was impaired as revealed by the spontaneous alternation in the T-maze task (Ruby et al. 2013) (Figure 3, vehicle treated animals). What could possibly account for these opposite results on the cognitive abilities of arrhythmic rats and arrhythmic hamsters?

Figure 3.

PTZ rescued memory in circadian-arrhythmic hamsters. The loss of circadian rhythms impaired spatial working memory as assessed by alternation behavior in a T-maze (left panel). The ability to discriminate a familiar object from a novel one was impaired in a novel object recognition test (right panel). Test performance of arrhythmic hamsters (ARR) after a 10-day injection regimen of PTZ was restored to levels observed in normal entrained animals (ENT). PTZ had no effect in ENT hamsters. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared to random chance performance. Data from Ruby et al. 2013.

The arrhythmic rats had no SCN and the arrhythmic hamsters had an intact SCN that was active, but not rhythmic. The activity of the SCNs of arrhythmic hamsters has been confirmed by the fact that the expression of clock genes continued in the SCNs of these animals, but that expression was arrhythmic (Grone et al. 2011). Furthermore, firing rates of SCN neurons are also arrhythmic in these animals, and maintain an average daily firing rate that does not differ from normal rhythmic hamsters (Margraf et al., 1992). Thus, it is reasonable to expect that some output of the SCN continued in the arrhythmic hamsters, but that output did not cycle. Since, as mentioned above, the SCN is a GABAergic nucleus, could the constant output of GABA in the arrhythmic hamsters create the same problem of over-inhibition as seen in the Ts65Dn mice?

Arrhythmic hamsters were treated with a 10-day regimen of daily ip injections of the GABAA receptor antagonist PTZ (1 mg/kg). The day after the PTZ injections ended, these animals were tested on the NOR and SA tasks, and they performed normally with no apparent learning and memory disability (Ruby et al. 2013) (Figure 3, PTZ treated animals). As with the Ts65Dn mice, the performance of the PTZ treated hamsters on the memory tests was still normal when the animals were tested one month later. These results support, but do not prove, the hypothesis that in the arrhythmic hamsters, continuous GABAergic output from their intact SCNs impairs learning and memory. The implication of this hypothesis is that in the intact animals, there is one particular phase of the daily rhythm when the SCN is actively inhibiting neural plasticity. What could be the adaptive significance of rhythmic, daily suppression of neural plasticity?

Long-term memory consolidation occurs during the sleep phase of the daily rhythm

As discussed earlier, sleep is critical for memory consolidation. What aspect of sleep is critical for this function? We hypothesized that continuity of NREM sleep was the critical factor, so we conducted an experiment on mice that were prepared for non-stressful optogenetic disruption of sleep continuity (Rolls et al. 2011). These mice received surgically implanted cannulae into their lateral hypothalami as well as EEG/EMG recording electrodes. Lentivirus containing constructs of the hypocretin promotor, light sensitive Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) cation channel, and mCherry red fluorescent protein were injected through the cannulae. Constructs injected into control mice did not include the ChR2 sequence. Prior to experiments, optical fibers were inserted through the cannulae so they resided just above the lateral hypothalami. Experiments consisted of training mice in the NOR task with testing 24 hrs. later. However, for 4 hrs. immediately following the NOR training, the mice were either: undisturbed, totally sleep deprived by gentle handling, or had their sleep fragmented by optogenetic stimulation of the hypocretinergic (Hct) cells in the lateral hypothalamus by pulses of blue light at 30, 60, 120, or 240 second intervals. Mice were allowed to sleep ad lib. for the remaining 20 hrs before testing.

Analysis of the EEG/EMG recordings revealed the effects of the optogenetic stimulation on sleep and on learning and memory. Except for the sleep deprivation group, the groups did not differ in their total amounts of REM or NREM sleep. However, the distribution of NREM bouts by duration showed that the ChR2 mice receiving optogenetic stimulation had more short bouts and fewer long bouts of NREM sleep than did the control or non-sleep deprived mice. Performance on the NOR test was normal in the control, non-sleep deprived mice. As expected, the mice that were sleep deprived for 4 hrs showed no discrimination between the two test objects. Performance differed in the groups receiving optogenetic stimulation of the Hct neurons. Mice whose sleep was fragmented at 30 or 60 sec. intervals showed no long-term memory of the NOR training. But, mice whose sleep was fragmented at 120 or 240 second intervals showed normal long-term memory of the NOR training (Figure 4). Our conclusion was that there was a minimal quantum of continuous NREM sleep that was essential for consolidation of the NOR training memory into long-term NOR memory.

Figure 4.

Effect of sleep fragmentation on novel object recognition memory. Mice were trained in the NOR task early in the light phase. Then for 4 hrs they were left undisturbed, were totally sleep deprived, or were subjected to different protocols of sleep fragmentation administered by brief trains of optogenetic stimulation of hypocretinergic cells at 30, 60, 120, or 240 sec. intervals. For the remaining 20 hrs they were allowed to sleep ad lib. until testing 24 hrs after training. Significant NOR memory was seen only in mice that slept ad lib. for 24 hrs. or had their early sleep fragmented at 120 or 240 sec. intervals. Data from Rolls et al. 2011 are presented as means +/− SEM. ***indicates P<.001.

A circadian influence on this process of memory consolidation during sleep was revealed by conducting the same experiment 12 hrs out of phase with the initial experiment. The NOR training in the initial experiment was at the beginning of the light phase – the sleep phase for the mice. In this second experiment, the NOR training was at the beginning of the dark phase – the active phase for the mice. Following training, the different groups were treated as in the previous experiment. NOR testing was conducted 24 hrs. later also during the dark phase. The results showed no deficits in NOR long-term memory due to any of the optogenetic stimulation regimes. What was the difference between this experiment and the initial one? In this experiment, the mice had undisturbed sleep during the normal daily sleep phase following the NOR training, even though that training was 12 hrs earlier at the beginning of the active phase. These results suggest that not just sleep, but sleep during the proper daily or circadian phase is essential for memory consolidation. That daily phase for the mice is the light phase, and this is the phase when the activity of the SCN is high. So, if the output of an active SCN is suppressing neural plasticity during the sleep phase of these mice, what could be its adaptive significance? Why should it be adaptive to suppress the ability to consolidate new memories?

Memories are vulnerable to change during the process of memory consolidation during sleep

The process of memory consolidation involves communication between different brain regions during sleep, and that communication involves several characteristic patterns of electrophysiological activity (Born and Wilhelm 2012). These patterns have been described most extensively in association with spatial learning in rats. Areas of the brain definitely involved in the formation of spatial memories are the hippocampus and the cortex. The close association of activities in these two brain areas is demonstrated by simultaneous recordings of local field potentials (LFPs). During exploration of a new environment or a novel object, the EEG is dominated by theta oscillations (4 – 10 Hz). Recordings from the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex show that the theta oscillations in these two areas are phase locked with the hippocampal activity preceeding the cortical activity by about 50 ms indicating a directionality of information flow (Siapas et al. 2005, Jones and Wilson 2005). What is that information and how is it coded?

Recordings of single units show that the initial experience in running a maze is coded in the sequences of firing of hippocampal neurons (Wilson and McNaughton 1993, 1994). These sequences are coordinated with the theta oscillation (Siapas et al. 2005). During subsequent NREM sleep these sequences are replayed on a faster (about 20x) time scale (Lee and Wilson 2002). These compressed sequences coincide with fast (about 200 Hz) LFP oscillations called sharp-wave ripples. The sharp-wave ripples with their associated compressed sequences of single cell firing can also be observed when the animal is resting. And, they can reflect both forward and reverse replay of the original experience (Carr et al. 2011). Selective suppression of these sharp-wave ripples during sleep following a spatial learning task impairs the subsequent memory of the animal for that task (Girardeau et al 2009). These results support the concept that the information encoded during training is contained in the neural activity associated with the sharp-wave ripples.

During NREM sleep, rapid sequences of single cell firing in the prefrontal cortex correlate closely with the fast sequences recorded in the hippocampus (Ji and Wilson 2007, Payrache 2009). In the cortex, these sequences are also expressed in association with sharp-wave ripples, and these sharp-wave ripples occur in phase with cortical spindle oscillations that originate in the thalamus (Siapas and Wilson 1998). Replays of these unique sequences observed in the cortex occur in frames that are set off by the slow rhythm (1 to 4 Hz) that characterizes NREM sleep (Molle et al. 2006, Molle and Born 2011). Extended replays may involve multiple bursts of sharp-wave ripples that extend over multiple slow wave frames (Davidson et al. 2009). These results and others show that reactivations of memories during sleep occur in a coordinated fashion in a brain network including the cortex, the thalamus and the hippocampus (Peyrache et al., 2011). The ensemble of these events are believed to be responsible for the reactivation-related improvement of memory consolidation.

The interpretation of these and other elegant electrophysiological studies of spatial memory processing is that the experience is coded in the hippocampus and the cortex, but consolidation of those relatively ephemeral memory traces into long-term storage involves communication between the hippocampus and the cortex facilitated by the various brain electrical rhythms that have been observed: sharp-wave ripples, theta waves, spindle waves, and slow waves. One model of this memory consolidation system characterizes the hippocampus as a rapid but short-term learning system and the cortex as a slow but durable learning system, and that the process of memory consolidation involves an interaction between these two systems with the rapid learning system reinforcing (or tutoring) the slow learning system (Born and Wilhelm 2012). These repeated and highly coordinated conversations between cell assemblies in the hippocampus and in the cortex occur during sleep. Our purpose in briefly reviewing this information on the electrophysiology of memory consolidation is to suggest that it is important to stabilize memory traces while these processes are taking place. High levels of neuroplasticity that characterize the waking brain could jeopardize the fidelity of the memory being consolidated.

Are memory traces vulnerable to alteration when they are being consolidated during NREM sleep? Several recent studies in both humans and mice have shown that memories can be modified during sleep. Two studies on humans showed that consolidation of a specific memory can be strengthened during sleep by introducing a sensory stimulus during the learning experience and then replaying that stimulus during subsequent sleep. In one study subjects were trained to locate card pairs on a computer screen grid. They were then tested following sleep by presenting one of each pair and asking the subject to indicate where the matching card should appear (Rasch et al. 2007). In some training sessions the subjects were subjected to the scent of roses. The rose scent was then reintroduced to the subjects during sleep. The results were that learning was significantly enhanced when the scent present during training was reintroduced during NREM sleep. The scent alone during sleep had no effect if it had not been present during learning. The vehicle had no effect. And, the scent had no effect if it were introduced during REM sleep. This study clearly showed that memories could be modified (in this case strengthened) during sleep.

A similar study using auditory stimuli showed that the sensory stimulation during sleep was specific to individual memories and not just to the overall process of memory consolidation. Rudoy et al. (2009) trained subjects to associate 50 images with their placement on a computer screen grid. Each image was paired with an appropriate sound – cat, meow; bell, ding; etc. The subjects were exposed to half of these sounds during subsequent NREM sleep. Positional recall during subsequent testing was significantly greater for the images that were recued by their sounds during sleep.

A study on mice demonstrated that the emotional valence of a memory could be strengthened or weakened during sleep (Rolls et al. 2013). Mice were exposed to foot shock that was paired with an odor as a conditioned stimulus (CS). When that odor was reintroduced to the mice during sleep immediately following the foot shock conditioning or even during the sleep phase of the following day, it did not disturb their sleep, but when the animals were re-exposed to the CS during subsequent wakefulness, they responded much more vigorously as measured by behavioral freezing (Figure 5a). The fear memory was clearly enhanced. In contrast, if the mice received bilateral micro-injections of anisomycin (a protein synthesis inhibitor) into the amygdala just prior to sleep, and the CS was introduced during sleep, the strength of the fear memory during subsequent wakefulness was reduced as evidenced by decreased freezing upon re-exposure to the CS (Figure 5b). These results show that the emotional valence of memories can be altered during sleep. The hypothesis is that the reintroduction of the CS reactivates the memory that then must be reconsolidated, and through this process, the emotional valence of the memory can be either enhanced or reduced.

Figure 5.

The effects of introducing the Conditioning Stimulus from a foot shock conditioning paradigm during subsequent sleep. A. Mice received foot shocks paired with an odor (the CS) at the beginning of the light phase. During the sleep phase beginning 24 hrs later the mice were re-exposed to the CS or to a control odor during episodes of NREM sleep. They were then tested 48 hrs. after conditioning in a neutral context by reintroduction of the CS or the control odor and measurements of time spent freezing were recorded. The re-exposure to the CS during sleep intensified the subsequent fear response. B. The experiment was repeated with a higher stimulus intensity, but the mice received bilateral injections of anisomycin or vehicle into the amygdala prior to the sleep phase. Responses to the CS in a neutral context were tested 48 hrs following the conditioning. Animals that received the anisomycin and were re-exposed to the CS during sleep showed a reduction in their subsequent fear response to the CS. Data from Rolls et al. 2013.

Additional experiments (Makam et al. unpublished) demonstrated a fundamental difference of reactivating the memory during wake or during sleep. When the foot-shocked mice were repeatedly re-exposed to the CS during wake in a neutral environment (not the environment in which the shocks had been experienced), there was gradual extinction of the freezing response as would be expected. That extinction was in contrast to the enhancement of the freezing response when the mice were re-exposed to the CS during sleep (Figure 5a). The interpretation of these results was that experiencing the CS during wake resulted in the coding of a new memory that associated the CS with a safe environment. This is in contrast to re-experiencing the CS during sleep which did not result in coding a new association, and therefore the emotional valence of the original memory was enhanced through the repeated reactivation/reconsolidation process. When the anisomycin was present, it interfered with that reconsolidation process and the fear memory was diminished. In another set of trials, the anisomycin treated mice were only re-exposed to the CS when they were spontaneously awake. This treatment had no effect on the subsequent fear response indicating that it interfered with the coding of a new memory associating the CS with a safe environment. Overall, these experiments on reactivating fear memories during wake and sleep support the idea that the memories are coded during wake and long-term consolidation occurs during sleep, and if reactivation and reconsolidation occurs during sleep, the memory trace can be altered.

A dramatic demonstration of the vulnerability of memories was a recent demonstration of the creation of a false memory (Ramirez et al. 2013). In this study, the optogenetic agent ChR2 was introduced into active hippocampal cells of mice while the animals were in a particular environment (neutral context). They were then foot-shocked in a different environment, which became a fear context. But, if the neurons that had incorporated ChR2 in the neutral context were activated by blue light during the foot-shock experience, the mice showed increased fear (freezing) when re-exposed to the neutral context. The interpretation was that the optogenetic stimulation reactivated the memory of the neutral context, and because that reactivation and subsequent reconsolidation was paired with the foot shock, the memory took on a new emotional valence. Although this experiment did not involve sleep recording, it is reasonable to expect that the new fear memory was consolidated during subsequent sleep.

Conclusion: A function of the SCN may be to stabilize memory traces as they are being consolidated during the daily sleep phase

The evidence reviewed in this paper leads us to propose that the daily phases of low learning and memory performance are not simply due to an ebb of brain alerting mechanisms, but rather they could be due to episodes of active suppression of neural plasticity through GABAergic inhibitory mechanisms. Over-activity of these mechanisms can lead to pathological learning disabilities as occur in Down syndrome and perhaps also in Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacological suppression of GABAergic inhibition restores learning and memory in mouse models of Down syndrome and AD (Fernandez et al. 2007, Rueda et al. 2008, Yoshike et al. 2008, Braudeau et al. 2011, Colas 2013). But, this GABAergic suppression only works when administered during the phase of the circadian cycle when the SCN is most active, pointing to the SCN as a critical player in the daily suppression of neural plasticity. Studies in which the SCN of rats were eliminated by electrolytic lesions produced no impairments of learning and memory, but rather resulted in performance at maximal levels at all times of day (Stephan and Kovacevic 1978).

Experiments on Siberian hamsters produced a very interesting contrast to the SCN lesion experiments. The fact that Siberian hamsters can be rendered arrhythmic by a DPS made them an attractive model for studying the effect of circadian arrhythmia on learning and memory. When these animals are rendered arrhythmic without destroying their SCN, they show severe learning and memory disability (Ruby et al. 2008). However, that disability can be reversed with pharmacological treatments that reduce GABAergic inhibition (Ruby et al. 2013). Taken together, these various results indicate an active role of the SCN in suppressing neural plasticity. What adaptive function could such suppression serve?

We have summarized some of the extensive evidence showing that memory consolidation occurs during sleep. We also show that specific memories can be reactivated during sleep and modified by various treatments (Rolls et al. 2013; Rasch et al. 2007; Rudoy et al. 2009). In conclusion, we propose that a function of the circadian system, and specifically the SCN in mammals, is to suppress neural plasticity during the sleep phase of the daily cycle when memory traces coded during the preceding active phase are being reactivated and consolidated into long-term storage. We suggest that the function of this suppression of neural plasticity is to protect the fidelity of the memory traces that are being consolidated.

Our proposal that the circadian system stabilizes memory traces during the process of consolidation is not intended to suggest that all forms of neural plasticity are suppressed during sleep. Early in this paper we referred to the elegant studies of Frank et al. 2001 demonstrating the sleep dependency of the physical processes of neuronal remodeling underlying plasticity of the visual system of monocularly deprived kittens. At another level, many studies in humans have shown that information acquired during wake is processed and integrated during sleep resulting in extraction of gist and insight (eg. Wagner et al. 2004; Ellenbogen et al. 2007; Diekelmann et al. 2010) and reviewed in detail by Born and Wilhelm (2012). Neural plasticity takes on many forms and plays numerous roles in the nervous system. At present we can only suggest that the circadian suppression of neural plasticity discussed in this paper applies specifically to the exchanges of information between the hippocampus and the cortex that are essential for memory consolidation during sleep.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply indebted to Bayarsaikhan Chuluun and Grace Hagiwara for assistance with experiments. We wish to acknowledge the following for financial support of our work: NIH grant 1R01MH095837, Down Syndrome Research and Treatment Foundation, Research Down Syndrome, NARSAD (fellowship to AR), and NSF (fellowship to MM).

References

- Benington J, Heller HC. Restoration of brain energy metabolism as the function of sleep. Prog in Neurobiol. 1995;45:347–360. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)00057-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbely A, Achermann P. Concepts and models of sleep regulation: an overview. Journal of Sleep Research. 1992;1:63–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1992.tb00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born J, Wilhelm I. System consolidation of memory during sleep. Psychological Research. 2012;76:192–203. doi: 10.1007/s00426-011-0335-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braudeau J, Delatour B, Duchon A, Pereira PL, Dauphinot L, de Chaumont F, Olivo-Marin JC, Dodd RH, Hérault Y, Potier MC. Specific targeting of the GABA-A receptor α5 subtype by a selective inverse agonist restores cognitive deficits in Down syndrome mice. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(8):1030–42. doi: 10.1177/0269881111405366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain SW, Chou T, Ralph MR. Circadian modulation of performance on an aversion-based place learning task in hamsters. Behav Brain Res. 2004;150:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr MF, Jadhav S, Frank LM. Hippocampal replay in the awake state: a potential substrate for memory consolidation and retrieval. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14:147–162. doi: 10.1038/nn.2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury D, Colwell CS. Circadian modulation of learning and memory in fear-conditioned mice. Behav Brain Res. 2002;15:95–108. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury D, Wang LM, Colwell CS. Circadian regulation of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2005;20:225–236. doi: 10.1177/0748730405276352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colas D, Valletta JS, Takimoto-Kimura R, Nishino S, Fujiki N, Mobley WC, Mignot E. Sleep and EEG features in genetic models of Down syndrome. Neurobiology of Disease. 2008;30:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colas D, Chuluun B, Warrier D, Blank M, Wetmore DZ, Buckmaster P, Garner CC, Heller HC. Short-term treatment with the GABAA antagonist pentylenetetrazole produces a sustained procognitive benefit in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;169:763–773. doi: 10.1111/bph.12169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa ACS, Grybko MJ. Deficits in hippocampal CA1 LTP induced by TBS but not HFS in the Ts65Dn mouse: a model of Down syndrome. Neuroscience letters. 2005;382:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F, Mitchison G. The function of dream sleep. Nature. 1983;304:111–114. doi: 10.1038/304111a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekelmann S, Born J. The memory function of sleep. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:113–1126. doi: 10.1038/nrn2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekelmann S, Born J, Wagner U. Sleep enhances false memories depending on general memory performance. Behavioral Brain Research. 2010;208:425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbogen JM, Hu PT, Payne JD, Titone D, Walker MP. Human relational memory requires time and sleep. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:7723–7728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700094104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez F, Morishita W, Zuniga E, Nguyen J, Blank M, Malenka RC, Garner CC. Pharmacotherapy for cognitive impairment in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Nature neuroscience. 2007;10:411–413. doi: 10.1038/nn1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Issa NP, Stryker MP. Sleep enhances plasticity in the developing visual cortex. Neuron. 2001;30:275–287. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardeau G, Benchenane K, Wiener SI, Buzsaki G, Zugaro MB. Selective suppression of hippocampal ripples impairs spatial memory. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1222–1223. doi: 10.1038/nn.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grone BP, Chang D, Bourgin P, Cao V, Fernald RD, Heller HC, Ruby NF. Acute light exposure suppresses circadian rhythms in clock gene expression. J Biol Rhythms. 2011;26:78–81. doi: 10.1177/0748730410388404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway FA, Wansley RA. Multiple retention deficits at periodic intervals after active and passive avoidance learning. Behav Biol. 1973a;9:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(73)80164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway FA, Wansley RA. Multiple retention deficits at periodic intervals after passive-avoidance learning. Science. 1973b;180:208–210. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4082.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne J. Why we sleep: The functions of sleep in humans and other mammals. New York: Oxford University Press; 1988. p. 319. [Google Scholar]

- Huber R, Ghilardi MF, Massimini M, Tononi G. Local sleep and learning. Nature. 2004;430:78–81. doi: 10.1038/nature02663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji D, Wilson MA. Coordinated memory replay in the visual cortex and hippocampus during sleep. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nn1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Duffy JF, Dijk DJ, Ronda JM, Dyal DM, Czeisler CA. Short-term memory, alertness and performance: a reappraisal of their relationship to body temperature. Journal of Sleep Research. 1992;1:24–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1992.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MW, Wilson MA. Theta rhythms coordinate hippocampal-prefrontal interactions in a spatial memory task. PLoS Biology. 2005;3:2187–2199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouvet M. Pardoxical sleep as a programming system. Journal Sleep Research. 1998;7 (suppl 1):1–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.7.s1.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleschevnikov AM, Belichenko PV, Villar AJ, Epstein CJ, Malenka RC, Mobley WC. Hippocampal long-term potentiation suppressed by increased inhibition in the Ts65Dn mouse, a genetic model of Down syndrome. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8153–8160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1766-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuger J, Obal F. A neuronal group theory of sleep function. Journal of Sleep Research. 1993;2:63–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1993.tb00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AK, Wilson MA. Memory of sequential experience in the hippocampus during slow wave sleep. Neuron. 2002;36:1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margraf RR, Puchalski W, Lynch GR. Absence of a daily neuronal rhythm in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of acircadian Djungarian hamsters. Neurosci Lett. 1992;142:175–178. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90367-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L, Helgadottir H, Molle M, Born J. Boosting slow oscillations during sleep potentiates memory. Nature. 2006;444:610–613. doi: 10.1038/nature05278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maquet P. The role of sleep in learning and memory. Science. 2001;294:1048–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.1062856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty D, Szymusiak R. Keeping cool: a hypothesis about the mchanisms and functions of slow-wave sleep. Trends in Neuroscience. 1990;12:480–7. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90081-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mednick S, Nakayama K, Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent learning: a nap is as good as a night. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6:697–698. doi: 10.1038/nn1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistlberger RE, de Groot MHM, Bossert JM, Marchant EG. Discrimination of circadian phase in intact and suprachiasmatic nuclei-ablated rats. Brain Res. 1996;739:12–18. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00466-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molle M, Yeshenkoo O, Marshall L, Sara SJ, Born J. Hippocampal sharp wave-ripples linked to slow oscillations in rat slow-wave sleep. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:62–70. doi: 10.1152/jn.00014.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molle M, Bergmann TO, Marshall L, Born J. Fast and slow spindles during the sleep slow oscillation: disparate coalescence and engagement in memory processing. Sleep. 2011;34:1411–1421. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrache A, Khamassi M, Benchenane K, Wiener SI, Battaglia FP. Replay of rule-learning related neural patterns in the prefrontal cortex during sleep. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:919–926. doi: 10.1038/nn.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrache A, Battaglia FP, Destexhe A. Inhibition recruitment in prefrontal cortex during sleep spindles and gating of hippocampal inputs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17207–17212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103612108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast BJ, Cisse YM, Cable EJ, Zucker I. Dissociation of ultradian and circadian phenotypes in female and male Siberian hamsters. J Biol Rhythms. 2012;27:287–98. doi: 10.1177/0748730412448618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasch B, Buchel C, Gais S, Born J. Odor cues during slow-wave sleep prompt declarative memory consolidation. Science. 2007;315:1426–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.1138581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan W, Eschenko O, Sara SJ. Hippocampal sharp wave/ripples during sleep for consolidation of associateive memory. PLoS One. 2009;4:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez S, Liu X, Lin R, Suh J, Pignatelli M, Redondo R, Ryan T, Tonegawa S. Creating a false memory in the hippocampus. Science. 2013;341:387–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1239073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves RH, Irving NG, Moran TH, Wohn A, Kitt C, Sisodia SS, Schmidt C, Bronson RT, Davisson MT. A mouse model for Down syndrome exhibits learning and behaviour deficits. Nature genetics. 1995;11:177–184. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls A, Colas D, Adamantidis A, Carter M, Lanre-Amos T, Heller HC, de Lecea L. Optogenetic disruption of sleep continuity impairs memory consolidation. PNAS. 2011;108:13305–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015633108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls A, Makam M, Kroeger D, Colas D, de Lecea L, Heller HC. Sleep to forget: interference of fear memories during sleep. Molec Psychiatry. 2013;18:1166–1170. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby NF, Fernandez F, Garrett A, Klima J, Zhang P, Garrett A, Sapolsky S, Heller HC. Spatial memory and object recognition are impaired by circadian arrhythmia and restored by the GABAA antagonist pentylenetetrazole. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e72433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby NF, Fernandez F, Zhang P, Klima J, Heller HC, Garner CC. Circadian locomotor rhythms are normal in Ts65Dn “Down Syndrome” mice and unaffected by pentylenetetrazole. J Biol Rhythms. 2009;25:63–66. doi: 10.1177/0748730409356202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby NF, Hwang CE, Wessells C, Fernandez F, Zhang P, Sapolsky R, Heller HC. Hippocampal-dependent learning requires a functional circadian system. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:15593–15598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808259105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby NF, Saran A, Kang T, Franken P, Heller HC. Siberian hamsters free run or become arrhythmic after a phase delay of the photocycle. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R881–R890. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.4.R881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda N, Flórez J, Martínez-Cué C. Chronic pentylenetetrazole but not donepezil treatment rescues spatial cognition in Ts65Dn mice, a model for Down syndrome. Neuroscience letters. 2008;433:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudoy JD, Voss JL, Westerberg CE, Paller KA. Strengthening individual memories by reactivating them during sleep. Science. 2009;326:1079. doi: 10.1126/science.1179013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz WJ, Reppert SM, Eagan SM, Moore-Ede MC. In vivo metabolic activity of the suprachiasmatic nuclei: a comparative study. Brain Res. 1983;274:184–187. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90538-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siapas AG, Lubenov E, Wilson MA. Prefrontal phase locking to hippocampal theta oscillations. Neuron. 2005;46:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siapas AG, Wilson MA. Coordinated interactions between hippocampal ripples and cortical spindles during slow-wave sleep. Neuron. 1998;21:1123–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan FK, Kovacevic NS. Multiple retention deficit in passive avoidance in rats is eliminated by suprachiasmatic lesions. Behav Biol. 1978;22:456–462. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(78)92565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature. 2005;437:1272–1278. doi: 10.1038/nature04286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickgold R, James LT, Hobson JA. Visual discrimination learning requires sleep after training. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:1237–1238. doi: 10.1038/81756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep and synaptic homeostasis: a hypothesis. Brain Research Bulletin. 2003;62:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner U, Gais S, Haider H, Verleger R, Born Sleep inspires insight. Nature. 2004;427:352–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP, Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent learning and memory consolidation. Neuron. 2004;44:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr T. A brain-warming function for REM sleep. Neuroscience Biobehavioral Reviews. 1992;16:379–97. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MA, McNaughton BL. Dynamics of the hippocampal ensemble code for space. Science. 1993;261:1055–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.8351520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M, McNaughton B. Reactivation of hippocampal ensemble memories during sleep. Science. 1994;265:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.8036517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshike Y, Kimura T, Yamashita S, Furudate H, Mizoroki T, Murayama M, Takashima A. GABA(A) receptor-mediated acceleration of aging-associated memory decline in APP/PS1 mice and its pharmacological treatment by picrotoxin. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]