Abstract

Previous studies indicate that conscious face perception may be related to neural activity in a large time window around 170-800ms after stimulus presentation, yet in the majority of these studies changes in conscious experience are confounded with changes in physical stimulation. Using multivariate classification on MEG data recorded when participants reported changes in conscious perception evoked by binocular rivalry between a face and a grating, we showed that only MEG signals in the 120-320ms time range, peaking at the M170 around 180ms and the P2m at around 260ms, reliably predicted conscious experience. Conscious perception could not only be decoded significantly better than chance from the sensors that showed the largest average difference, as previous studies suggest, but also from patterns of activity across groups of occipital sensors that individually were unable to predict perception better than chance. Additionally, source space analyses showed that sources in the early and late visual system predicted conscious perception more accurately than frontal and parietal sites, although conscious perception could also be decoded there. Finally, the patterns of neural activity associated with conscious face perception generalized from one participant to another around the times of maximum prediction accuracy. Our work thus demonstrates that the neural correlates of particular conscious contents (here, faces) are highly consistent in time and space within individuals and that these correlates are shared to some extent between individuals.

Introduction

There has been much recent interest in characterizing the neural correlates of conscious face perception, but two critical issues remain unresolved. The first is the time at which it becomes possible to determine conscious face perception from neural signals obtained after a stimulus is presented. The second is whether patterns of activity related to conscious face perception generalize meaningfully across participants, thus allowing comparison of the neural processing related to the conscious experience of particular stimuli between different individuals. Here, we addressed these two questions using MEG to study face perception during binocular rivalry. We also examined several more detailed questions, including which MEG sensors and sources were the most predictive, which frequency bands were predictive, and how to increase prediction accuracy based on preprocessing and pre-selection of trials.

The neural correlates of conscious face perception have only been studied in the temporal domain in a few recent EEG studies. The most commonly employed strategy in those studies was to compare neural signals evoked by masked stimuli that differ in stimulus-mask onset asynchrony that results in differences in visibility of the masked stimulus (Babiloni et al., 2010; J. A. Harris, Wu, & Woldorff, 2011; Liddell, Williams, Rathjen, Shevrin, & Gordon, 2004; Pegna, Darque, Berrut, & Khateb, 2011; Pegna, Landis, & Khateb, 2008). However, because all but one of these studies (Babiloni et al., 2010) compared brief presentations with long presentations, the stimuli (and corresponding neural signals) differed not only in terms of whether or not they were consciously perceived, but also in terms of their duration. Conscious perception of a stimulus was thus confounded by physical stimulus characteristics (Lumer, Friston, & Rees, 1998). Moreover, all of these earlier studies used conventional univariate statistics, comparing (for example) the magnitude of averaged responses between different stimulus conditions across participants. Such approaches are biased towards single strong MEG/EEG sources and may overlook distributed, yet equally predictive information.

It remains controversial whether relatively early or late event-related potential/field (ERP/ERF) components predict conscious experience. The relatively early components in question are the N170 found around 170ms after stimulus onset and a later response at around 260ms (sometimes called P2 or N2 (depending on the analyzed electrodes) and sometimes P300 or P300-like). The N170 is sometimes found to be larger for consciously perceived faces than for those that did not reach awareness (Babiloni et al., 2010; J. A. Harris et al., 2011; Pegna et al., 2011), yet this difference is not always found (Liddell et al., 2004; Pegna et al., 2008). Similarly, the P2/N2 correlated positively with conscious experience in one paper (Babiloni et al., 2010) and negatively in others (Liddell et al., 2004; Pegna et al., 2011). Additionally, both the N170 (Pegna et al., 2008) and the P2/N2 (Liddell et al., 2004; Pegna et al., 2011) depend on invisible stimulus characteristics, suggesting that these components reflect unconscious processing (but see J. A. Harris et al., 2011).

Late components are found between 300 and 800ms after stimulus presentation. Two studies point to these components (300-800ms) as reflecting conscious experience of faces (Liddell et al., 2004; Pegna et al., 2008), yet these late components are only present when stimulus durations differ between conscious and unconscious stimuli and not when stimulus duration is kept constant across the entire experiment and stimuli are classified as conscious or unconscious by the participants (Babiloni et al., 2010).

Here, we therefore sought to identify the time range for which neural activity was diagnostic of the contents of conscious experience in a paradigm where conscious experience changed, but physical stimulation remained constant. We used highly sensitive multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) of MEG signals to examine the time when the conscious experience of the participants viewing intermittent binocular rivalry (Breese, 1899; Leopold, Wilke, Maier, & Logothetis, 2002) could be predicted. During intermittent binocular rivalry, two different stimuli are presented on each trial – one to each eye. Although two different stimuli are presented, the participant typically reports perceiving only one image and this image varies from trial to trial. In other words, physical stimuli are kept constant, but conscious experience varies from trial to trial. This allowed us to examine whether and when MEG signals predicted conscious experience on a per-participant and trial-by-trial basis. Consistent with previous studies using multivariate decoding, we collected a large dataset from a relatively small number of individuals (Carlson, Hogendoorn, Kanai, Mesik, & Turret, 2011; Haynes, Deichmann, & Rees, 2005; Haynes & Rees, 2005; Raizada & Connolly, 2012), employing a case-plus-replication approach supplemented with group analyses where necessary.

Having established the temporal and spatial nature of the neural activity specific to conscious face perception by use of MVPA applied to MEG signals, we further sought to characterize how consistently this pattern generalized between participants. If the pattern of MEG signals in one participant was sufficient to provide markers of conscious perception that could be generalized to other participants, this would provide one way to compare similarities in neural processing related to the conscious experience of particular stimuli between different individuals.

After having examined our two main questions, two methods for improving multivariate classification accuracy were also examined: Stringent low-pass filtering to smooth the data and rejection of trials with unclear perception. Next, univariate and multivariate prediction results were compared in order to find correlates of conscious face perception that are not revealed by univariate analyses. This analysis was performed at the sensor level as well as on activity reconstructed at various cortical sources. In addition to these analyses, it was examined whether decoding accuracy was improved by taking into account information distributed across the ERF or by using estimates of power in various frequency bands.

Experimental methods

MEG signals were measured from healthy human participants while they experienced intermittent binocular rivalry. Participants viewed binocular rivalry stimuli (images of a face and a sinusoidal grating) intermittently in a series of short trials (Fig. 1A) and reported their percept using a button press. This allowed us to label trials by the reported percept, yet time-lock analyses of the rapidly changing MEG signal to the specific time of stimulus presentation instead of relying on the timing of button press reports, which are both delayed and variable with respect to the timing of changes in conscious contents. The advantages of this procedure have been described elsewhere (Kornmeier & Bach, 2004).

Figure 1. Experimental design and results.

A) Experimental design. Rivaling stimuli (face/grating) were presented for trials lasting ~800ms separated by blank periods of ~900ms. Stimuli were dichoptically presented to each eye and rotated in opposite directions at a rate of 0.7 rotations per second. Participants reported which of the two images they perceived with a button press as soon as they saw one image clearly. If perception did not settle, or if the perceived image changed during the trial, the participant reported mixed perception with a third button press. B) Classification procedure. Support vector machines (SVM) were trained to distinguish neuromagnetic activity related to conscious face and grating perception for each participant. The SVMs were then used to decode the perception of 1) the same participant on different trials (top panel), and 2) each of the other participants (bottom panel). C) Left: Reaction time (RT) as a function of perceptual report. Right: RT as a function of trial number after a perceptual switch. D) RT as a function of time after a perceptual switch by perception. The decrease in RT for non-mixed perception indicates that perception on average is clearer far from a perceptual switch than immediately after. Trials for which the same percept has been reported at least 10 times are here-after referred to as “stable” whereas other trials are referred to as “unstable”.

Participants

8 healthy young adults (6 females) between 21 and 34 years of age (mean=26.0, SD=3.55) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision gave written informed consent to participate in the experiment. The experiments were approved by the UCL Research Ethics Committee.

Apparatus and MEG recording

Stimuli were generated using the MATLAB toolbox Cogent (http://www.vislab.ucl.ac.uk/cogent.php). They were projected onto a 19” screen (resolution: 1024×768 pixels; refresh rate: 60Hz) using a JVC D-ILA, DLA-SX21 projector. Participants viewed the stimuli through a mirror stereoscope positioned at approximately 50cm from the screen. MEG data was recorded in a magnetically shielded room with a 275 channel CTF Omega whole-head gradiometer system (VSM MedTech, Coquitlam, BC, Canada) with a 600Hz sampling rate. After participants were comfortably seated in the MEG, head localizer coils were attached to the nasion and 1 cm anterior (in the direction of the outer canthus) of the left and right tragus to monitor head movement during recording.

Stimuli

A red Gabor patch (contrast = 100 %, spatial frequency = 3 cycles/degree, standard deviation of the Gaussian envelope = 10 pixels) was presented to the right eye of the participants, and a green face was presented to the left eye (Fig. 1A). To avoid piecemeal rivalry where each image dominates different parts of the visual field for the majority of the trial, the stimuli rotated at a rate of 0.7 rotations per second in opposite directions, and to ensure that stimuli were perceived in overlapping areas of the visual field, each stimulus was presented within an annulus (inner/outer r = 1.3/1.6 degrees of visual angle) consisting of randomly oriented lines. In the center of the circle was a small circular fixation dot.

Procedure

During both calibration and experiment participants reported their perception using three buttons each corresponding to either face, grating, or mixed perception. Participants swapped the hand used to report between blocks. This was done in order to prevent the classification algorithm from associating a perceptual state with neural activity related to a specific motor response. In order to minimize perceptual bias (Carter & Cavanagh, 2007), the relative luminance of the images was adjusted for each participant until each image was reported equally often (+/− 5%) during a one minute long continuous presentation.

Each participant completed 6-9 runs of 12 blocks of 20 trials, i.e. 1440-2160 trials were completed per participant. On each trial, the stimuli were displayed for approximately 800ms. Each trial was separated by a uniform gray screen appearing for around 900ms. Between blocks, participants were given a short break of 8 seconds. After each run, participants signaled when they were ready to continue.

Preprocessing

Using SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/), data were downsampled to 300Hz and high-pas filtered at 1Hz. Behavioral reports of perceptual state were used to divide stimulation intervals into face, grating or mixed epochs starting 600ms before stimulus onset and ending 1400ms after. Trials were baseline-corrected based on the average of the 600ms pre-stimulus activity. Artifacts were rejected at a threshold of 3 picotesla (pT). On average 0.24% (SD=0.09) of the trials were excluded for each participant due to artifacts.

Event related field (ERF) analysis

Traditional, univariate event related field (ERF) analysis was first performed. For this analysis, data were filtered at 20Hz using a 5th order Butterworth low-pass filter, and face and grating perception trials were averaged individually using SPM8.

Source analysis

Sources were examined using the multiple sparse priors (MSP) (Friston et al., 2008) algorithm. MSP operates by finding the minimum number of patches on a canonical cortical mesh that explain the largest amount of variance in the MEG data, this tradeoff between complexity and accuracy is optimized through maximization of model evidence. The MSP algorithm was first used to identify the electrical activity underlying the grand average face-grating contrast maps at a short time window around the M170 and the P2m (100ms to 400ms after stimulus onset). Afterwards, the MSP algorithm was used to make a group-level source estimation based on template structural MR scans using all trials (over all conditions) from all 8 participants. The inverse solution restricts the sources to be the same in all participants, but allows for different activation levels. This analysis identified 33 sources activated at stimulus onset (see Table 1). Activity was extracted on a single trial basis across the 33 sources for each scan of each participant and thus allowed for analyses to be performed in source space.

Table 1. Sources.

The 33 sources judged to be most active across all trials independently of perception/stabilization across all participants. Sources were localized using multiple sparse priors (MSP) to solve the inverse problem. Source abbreviations: V1: Striate cortex; OCC: Occipital lobe; OFA: Occipital face area; STS: Superior temporal sulcus. IT: Inferior temporal cortex; SPL: Superior parietal lobule; PC: Precentral cortex; MFG: Middle frontal gyrus; PFC: Prefrontal cortex; OFC: Orbitofrontal cortex. Navigational abbreviations: l: Left hemisphere; r: Right hemisphere; p: Posterior; a: Anterior; d: Dorsal; v: Ventral.

| Source | Area | Name | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1 | Occipital Lobe | lV1 | −2 | −96 | 5 |

| 2 | rV1 | 12 | −98 | −1 | |

| 3 | lvOCC1 | −16 | −94 | −18 | |

| 4 | rvOCC1 | 21 | −96 | −17 | |

| 5 | lvOCC2 | −14 | −80 | −13 | |

| 6 | rvOCC2 | 15 | −80 | −12 | |

| 7 | ldOCC | −18 | −81 | 40 | |

| 8 | rdOCC | 19 | −82 | 40 | |

|

|

|||||

| 9 | Occipital Face area | lOFA | −38 | −80 | −15 |

| 10 | rOFA | 39 | −80 | −15 | |

|

|

|||||

| 11 | Face-specific | lpSTS1 | −54 | −63 | 9 |

| 12 | rpSTS1 | 53 | −63 | 13 | |

| 13 | lpSTS2 | −55 | −50 | 23 | |

| 14 | rpSTS2 | 54 | −49 | 18 | |

| 15 | lpSTS3 | −59 | −33 | 10 | |

| 16 | rpSTS3 | 55 | −34 | 7 | |

| 17 | lFFA | −53 | −51 | −22 | |

| 18 | rFFA | 52 | −52 | −22 | |

|

|

|||||

| 19 | Parietal | lSPL1 | −40 | −37 | 60 |

| 20 | rSPL1 | 36 | −37 | 60 | |

| 21 | lSPL2 | −33 | −65 | 49 | |

| 22 | rSPL2 | 36 | −64 | 46 | |

| 23 | lSPL3 | −41 | −35 | 44 | |

| 24 | rSPL3 | 39 | −36 | 44 | |

|

|

|||||

| 25 | Motor | lPC | −54 | −12 | 15 |

| 26 | rPC | 54 | −11 | 13 | |

|

|

|||||

| 27 | Frontal | laMFG1 | −40 | 18 | 27 |

| 28 | raMFG1 | 38 | 18 | 26 | |

| 29 | laMFG2 | 38 | 41 | 19 | |

| 30 | lOFC1 | −24 | 7 | −18 | |

| 31 | rOFC1 | 22 | 8 | −19 | |

| 32 | lOFC2 | −43 | 31 | −16 | |

| 33 | rOFC2 | 41 | 35 | −15 | |

Multivariate prediction analysis

Multivariate pattern classification of the evoked responses was performed using the linear Support Vector Machine (SVM) of the MATLAB Bioinformatics Toolbox (Mathworks). The SVM decoded the trial type (face or grating) independently for each time point along the epoch. Classification was based on field strength data as well as power estimates in separate analyses.

Conscious perception was decoded within and between participants. For within-subject training/testing, 10-fold cross-validation was used (Fig. 1B). For between-subject training/testing, the SVM was trained on all trials from a single participant and tested on all trials of each of the remaining participants. The process was repeated until data from all participants had been used to train the SVM (Fig. 1B).

In order to decrease classifier training time (for practical reasons), the SVM used only 100 randomly selected trials of each kind (200 in total). As classification accuracy cannot be compared between classifiers trained on different numbers of trials, participants were excluded from analyses if they did not report 100 of each kind of analyzed trials. The number of participants included in each analysis is reported in the “Results” section.

In addition to the evoked response analysis, a moving window discrete Fourier transform using was used to make a continuous estimate of signal power in selected frequency bands over time: Theta: 3-8Hz, Alpha: 9-13Hz, low beta: 14-20Hz, high beta: 21-30Hz as well as 6 gamma bands in the range 31-90Hz, each consisting of 10Hz (Gamma1, for instance, would thus be 31-40Hz) but excluding the 50Hz band. The duration of the moving window was set to accommodate at least 3 cycles of the lowest frequency within each band (e.g. for theta (3-8Hz) the window was 900ms).

Statistical testing

All statistical tests were two-tailed. Comparisons of classification accuracies were performed on a within-subject basis using the binomial distributions of correct/incorrect classifications. In order to show the reproducibility of the within subject significant effects across individuals we used the cumulative binomial distribution:

| (1) |

Where n is the total number of participants, the within-subject significant criterion is p (=0.05) and x is the number of participants that reach this criterion and is the binomial coefficient.

Prediction accuracy for each power envelope was averaged across a 700ms time window after stimulus presentation (211 sampling points) for each participant. Histogram inspection and Shapiro-Wilk tests showed that the resulting accuracies were normally distributed. One sample t-tests (N=8) were used to compare the prediction accuracy level of each power band to chance (0.5). Bonferroni correction for 10 comparisons was used as 10 power bands were analyzed.

Results

EEG research points to the N170 and the component sometimes called the P2 as prime candidates for the correlates of conscious face perception (following convention, we shall call these M170 and P2m hereafter), but later sustained activity around 300-800ms may also be relevant. In order to search for predictive activity even earlier than this, activity around the face-specific M100 was also examined. Before analyses, trials with unclear perception were identified and excluded from subsequent analyses.

Identification of unclear perception based on behavioral data

Analyses were optimized by contrasting only face/grating trials on which perception was as clear as possible. Participants generally reported perception to be unclear in two ways, both of which have been observed previously (see Blake, 2001). First, participants reported piecemeal rivalry where both images were mixed in different parts of the visual field for the majority of the trial. Such trials were not used in the MEG analyses. Second, participants sometimes experienced brief periods (<200ms) of fused or mixed perception at the onset of rivalry. Participants were not instructed to report this initial unclear perception if a stable image was perceived after a few hundred milliseconds in order to keep the task simple. To minimize the impact of this type of unclear perception on analyses, we exploited the phenomenon of stabilization that occurs during intermittent rivalry presentations, which will be explained below.

On average, participants reported face perception on 45.5% (SD=15.1) of the trials, grating perception on 42.6% (SD=16.1), and mixed perception on 11.9% (SD=10.6). Mean RT across participants (N=8) was 516ms (SD=113) overall, and the frequency histogram of the data in Fig. 1A shows the variance in RT. Average RT was 497ms (SD=112) for face perception, 493ms (SD=134) for grating perception, and 628ms (SD=117) for mixed perception, reflecting a longer decision making time when perception was unclear (Fig. 1C).

During continuous rivalry, the neural population representing the dominant image strongly inhibits the competing neural population, but as adaptation occurs, inhibition gradually decreases until perception switches after a few seconds (Freeman, 2005; Noest, van Ee, Nijs, & van Wezel, 2007; Wilson, 2003, 2007). In contrast, during intermittent presentation adaptation does not easily reach the levels at which inhibition decreases significantly while at the same time the percept-related signal stays high possibly due to increased excitability of the dominant neurons (Wilson, 2007) or increased sub-threshold elevation of baseline activity of the dominant neurons (Noest et al., 2007). Behaviorally this results in a high degree of stabilization, i.e. the same image being perceived on many consecutive trials, and a swift inhibition of the non-dominant image is thus to be expected on such stabilized trials. This should result in minimization of the brief period of fused or mixed perception, causing a faster report of the perceived image. We hypothesized that stabilization-related perceptual clarity builds up gradually across trials following a perceptual switch, and tested this by examining reaction times. If the hypothesis is correct, a negative correlation between RT and trial number counted from a perceptual switch would be expected for face/grating, but not for mixed perception. In other words, when stabilization increases across time, perceptual clarity is expected to increase and RT to decrease. When perception remains mixed, no such effect is expected even though participants press the same response button on consecutive trials.

As can be seen in Fig. 1D, log-transformed RT did indeed correlate negatively with time after a perceptual switch for face/grating perception (r = −0.39, p<0.001), but not for mixed perception (r = −0.11, p=0.37). This gradual build-up of stabilization-related perceptual clarity was confirmed in additional MEG analyses to be reported elsewhere (Sandberg et al., in preparation). Based on both these findings, we analyzed only MEG trials for which participants had reported at least 10 identical percepts. We refer to these as “stable trials”. A similar criterion was used by Brascamp et al. (2008). After artifact rejection and rejection of unstable trials, on average 396 face perception and 393 grating perception trials remained per participant.

The impact of rejection of unstable trials on decoding accuracy is reported in “Appendix: Improving decoding accuracy”. Please note that results remain highly significant without rejection of these trials.

Univariate event-related field (ERF) and source differences

We first examined which ERF components varied with conscious perception. We calculated a face-grating contrast using stable trials, and as shown in Fig. 2A, activity related to face perception differed clearly from that related to grating perception particularly at two time points, 187ms (M170) and 267ms (P2m), after stimulus presentation. The three face-specific peaks, the M100, M170 and P2m are shown in Fig. 2B-C. Fig. 2D shows that the difference at 187ms was localized almost exclusively to temporal sensors.

Figure 2. Univariate analyses on averaged field strength data (stable trials).

A) Topographic maps showing face-grating contrast. The largest differences were found at 187ms and 267ms after stimulus onset. B) Activity at the sensor for which the largest M100 difference was found (MRO32). Generally, only small differences were observed. C) Activity at the sensor for which the largest M170 and P2m difference was found (MRT44). Notice that face-related activity is larger than grating-related at both peaks. D) Map of sensor location. E) Posterior probability map of estimated cortical activity underlying the average difference between face and grating perception in the 100-400ms time window using the MSP algorithm. The grey-black scale shows the regions of the cortical surface with greater than 95% chance of being active. The solution explains 97% of the measured data. The image is plotted at t=180ms, the peak latency at the peak source location (38,−81,−17). The activity pattern was consistent with activation of the face processing network (Haxby et al., 2000).

The electrical activity underlying the grand average face-grating contrast maps was estimated using the MSP algorithm, and the solution explained 97% of the variance in the MEG signals for the period from 100ms to 400ms after stimulus onset. The posterior probability map, showing those cortical locations with 95% probability of having non-zero current density at t=180ms (the time of maximal activity difference) is plotted in Fig. 2E. The activity pattern was strikingly consistent with activation of the face-processing network (Haxby, Hoffman, & Gobbini, 2000) with the right occipital face area (OFA) indicated as the largest source.

Within-subject decoding of conscious perception

In order to determine the times when MEG activity accurately predicted conscious experience, multivariate SVM classifiers were trained to decode perception on each trial. To demonstrate that results remained significant without any pre-selection of trials, classifiers were first trained on 1-20Hz filtered data from 100 randomly selected trials of each kind (face/grating), thus including both stable and unstable trials.

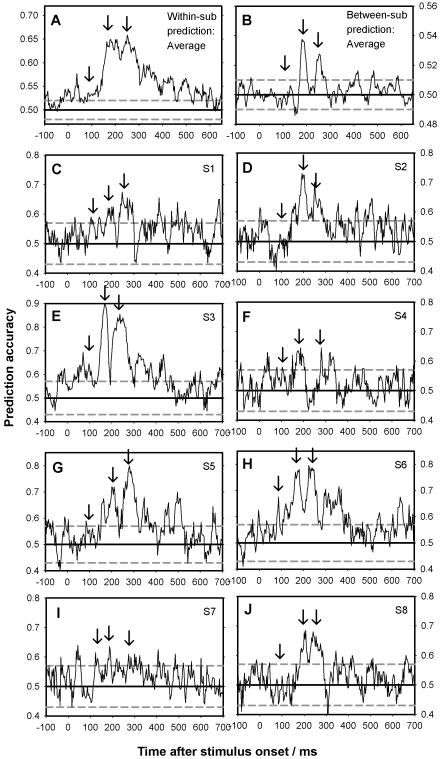

Conscious perception was predicted at a level significantly above chance in the 120-300ms time window with average classification performance peaking at around 180ms and 260ms after stimulus onset (Fig. 3A, C-J) (the third, smaller peak at around 340ms was not observed for all participants and was not replicated in the between-subjects analyses). Activity after 350ms only predicted conscious experience to a very small degree or not at all. The temporal positions of the two peaks in classification performance corresponded well with the M170 and the P2m. Based on the binomial distribution of correct/incorrect classifications, classification accuracy was above chance at the p<0.05 level at 187ms for all 8 participants and at 270ms for 7 out of 8 participants. The probability of finding significantly above chance within-subject prediction accuracies for 7 or 8 of the total 8 participants in this case-study-plus-replication design by chance was p=6.0*10−9 and p=3.9*10−11 respectively (uncorrected for comparisons over latencies). At no time point around the M100 were significant within-subject differences found for more than 2 participants, giving a combined p=0.057, thus indicating that little or no group differences between face and grating perception were present at the M100. Overall the main predictors of conscious perception thus appeared to be the M170 (at 187ms) and to a slightly lesser extent the P2m (at 270ms).

Figure 3. Prediction accuracy across time using all trials.

Average prediction accuracy for all trials (stable and unstable) across participants is plotted based on the single trial, 1-20Hz filtered MEG field strength data as a function of time. A support vector machine (SVM) was trained to predict reported perception (face vs. grating) for each time point. The dotted gray line indicates the threshold for which a binomial distribution of the same number as the total number of trials the prediction is performed upon is different from chance (uncorrected). A) Average within-subject prediction accuracy for all eight participants is plotted (i.e. classification accuracy when the SVM was trained and tested on data from the same participant). Notice the two clear peaks (the M170 at 187ms and the P2m at 267ms) indicated by the second and third arrows. The first arrow indicates the expected timing of the M100. B) Average between-subject prediction accuracy for all between-subject tests across time (i.e. classification accuracy when the SVM was trained and tested on data from different participants). C-J) Prediction accuracy for each individual participant for the within-subject predictions.

Having determined that conscious experience could be predicted within participants in the 120-300ms time range, SVM classifiers were trained on data from one participant to decode the conscious content of a different participant (Fig. 1B bottom panel).

Between-subject decoding of conscious perception

For between-subject decoding, peaks were observed around the M170 and the P2m, but no above-chance accuracy was observed around the M100 (Fig. 3B). Accuracy was significantly above chance for 7 of 8 participants at 180ms and for 5 of 8 participants at 250ms. The probability of observing these within-participant repeated replications were p=6.0*10−9 and p=1.5*10−5 respectively. No significant differences were found around the M100.

Overall, the M170 was thus found to be the component that predicted conscious experience most accurately and significantly both within and between individuals, closely followed by the P2m. Before initiating further analyses, we examined how different analysis parameters might change decoding accuracy as described below.

We hypothesized that decoding accuracy could be increased in two ways: by rejecting trials for which perception was not completely clear, and by applying a more stringent filter to the data. Participant’s reports (see Results, above) suggested that the probability of clear perception on a given trial increased the further away the trial is from a perceptual switch. We thus tested classifiers trained on stable vs. unstable trials, and on 1-300Hz, 1-20Hz, and 2-10Hz filtered data. This analysis is reported in the “Appendix: Improving decoding accuracy” and showed that the best results were obtained using 2-10Hz filtered data from stable trials. Please note that this should not be taken as an indication that higher frequencies are considered noise in a physiological sense, simply that the ERF components in the present experiment may be viewed as half-cycles of around 3-9Hz and that the temporal smoothing of a 10Hz low-pass filter may have minimized individual differences in latency of the M170 and P2m.

Moreover, in the Appendix we also report an analysis of the predictive ability of power in various frequency bands (“Appendix: Decoding using power estimations”. This analysis shows that the low frequencies dominating the ERF components are the most predictive, yet prediction accuracy was never better than for analyses based on the evoked field strength response. The following analyses are thus performed on 2-10Hz filtered data from the 6 participants who reported at least 100 trials of stable face/grating perception.

Identification of predictive sensors

One advantage of multivariate decoding over univariate analyses is the sensitivity to distributed patterns of information. We therefore examined which group of sensors was most predictive of conscious face perception independently of whether these sensors showed the largest grand average difference.

Identification of predictive sensors was based on the standard CTF labeling of sensors according to scalp areas as seen in Fig. 2D. First, the number of randomly selected sensors distributed across the scalp required to decode perception accurately around the most predictive component, the M170, was examined. Decoding accuracy peaked at around 50 sensors, thus indicating that a group of >10 sensors from every site was enough to decode perception significantly above chance (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Predictability by sensor location (stable trials).

Six participants had enough trials to train the classifiers on stable trials alone. The figure plots prediction accuracy based on 2-10Hz filtered data from these participants. Dotted gray line represents the 95% binomial confidence interval around chance (uncorrected). A) Prediction accuracy as a function of the number of randomly selected sensors from all scalp locations. B) Group-level prediction accuracy as a function of sensor location. Left/Right indicate that classifier is trained on left/right hemisphere sensors respectively. Other sensors locations can be seen in figure 2D. C) Average prediction accuracy for within-subject tests across time when classifier is trained/tested using occipital and temporal sensors respectively. D) Prediction accuracy at the time of the M170 when the classifier is trained on single sensors (i.e. univariate classification) or all sensors (multivariate classification) in occipital/temporal locations. Each grey bar plots accuracy for a single sensor. Black bars plot group-level performance.

Next, the ability of the sensors in one area alone to decode conscious perception at the M170 was examined (Fig. 4B). As expected, low decoding accuracy was found for most sites where previous analyses showed no grand average difference (central sensors: 56.7%, parietal sensors: 60.5%, and frontal sensors: 57.9%) while decoding accuracy was high for temporal sensors (75.2%) where previous analyses had shown a large grand average difference. However, decoding accuracy was numerically better when using occipital sensors (78.0%). This finding was surprising as previous analyses had indicated little or no grand average difference over occipital sensors.

Therefore, the predictability of single sensor data was compared to the group-level decoding accuracy. In Fig. 4D, individual sensor performance is plotted for occipital and temporal sensors. The highest single sensor decoding accuracy was achieved for temporal sensors showing the greatest grand average difference in the ERF analysis. In the plots, it can be seen that for occipital sensors, the group level classification (black bar) is much greater than that of the single best sensor whereas this is not the case for temporal sensors. In fact, a prediction accuracy of 74.3% could be achieved using only 10 occipital sensors with individual chance-level performance (maximum of 51.3%).

Just as multivariate classification predicted conscious face perception at sensors that were at chance individually, it is possible that perception might be decoded using multiple time points for which individual classification accuracy was at chance. It may also be possible that the information at the P2m was partially independent from the information at the M170, causing joint classification accuracy to increase beyond individual classification. For these reasons, we examined classification accuracy when the SVM classifiers were trained on data from multiple time points. The formal analysis is reported in “Appendix: Decoding using multiple time points” and shows that including a wide range of time points around each peak (11 time points, 37ms of data) does not improve decoding accuracy. Neither does inclusion of information at both time points in a single classifier, and finally, decoding of consciousness perception is not improved above chance using multiple time points individually at chance.

Decoding in source space

Our finding that signals from single time points at the sensors close to visual areas of the brain were the most predictive does not necessarily mean, however, that the activity at these sensors originates from visual areas. In order to test this, analyses of sources are necessary. Therefore, activity was reconstructed at the 33 sources that were most clearly activated by the stimuli in general (i.e. independently of conscious perception), and decoding was performed on these data. The analysis was performed on 2-10Hz filtered data from stable trials using the 6 participants who had 100 or more stable trials with reported face/grating perception.

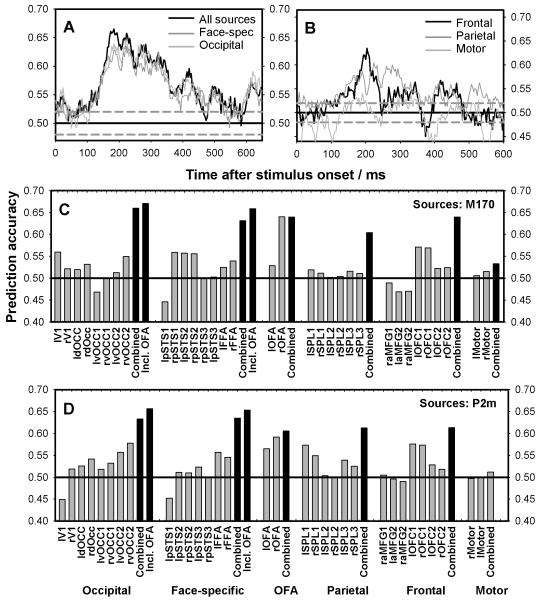

First, decoding accuracy was examined across time when classifiers were trained/tested on data from all sources (Fig 5A). Next, classifiers were trained on groups of sources based on cortical location (see Table 1). Comparisons between the accuracies achieved by each group of sources may only be made cautiously as the number of activated sources differs between areas, and the classifiers were thus based on slightly different numbers of features. The occipital, the face-specific, the frontal, and the parietal groups, however, included almost the same number of sources (8, 8, 7, and 6 respectively). Overall, Fig. 5A-B shows that for all sources, decoding accuracy peaked around the M170 and/or the P2m, and that conscious perception could be predicted almost as accurately from 8 occipital or face-specific sources as from all 33 sources combined. This was not found for any other area.

Figure 5. Predictability by source location (stable trials).

Six participants had enough trials to train the classifiers on stable trials alone. The figure plots prediction accuracy based on 2-10Hz filtered data from these participants. Prediction is based on reconstructed activity at the most activated sources. Dotted gray line represents the 95% binomial confidence interval around chance (uncorrected). A-B) Average prediction accuracy across time when classifier was trained/tested using data from occipital, face-specific, frontal, parietal, and motor sources respectively. C-D) Prediction accuracy at the time of the M170 (C) and the P2m (D) when the classifier is trained on single sources (i.e. univariate classification) or all sources in each area (multivariate classification). Each grey bar plots accuracy for a single source. Black bars plot group-level performance.

Decoding accuracy was also calculated for the individual sources at the M170 (Fig. 5C) and the P2m (Fig. 5D) using the individual peaks of each participant (see Fig. 3). The single most predictive source with an accuracy of 64% at the M170 and 59% at the P2m was the right OFA (occipital face area) – a face-sensitive area in the occipital lobe. The majority of the remaining predictive sources were found in occipital and face-specific areas with the exception of a ventral medial prefrontal area, and possibly an area in the superior parietal lobe around the P2m. The peak classification accuracies for groups of sources (black bars in Fig. 5C-D) were also the highest for occipital and face-specific sources, yet when combined the sources in other areas also became predictive above chance. Overall, it appeared that the most predictive sources were in the visual cortex although information in other areas also predicted conscious perception. Generally, little or no difference was observed regarding which sources were predictive at the M170 and at the P2m.

Discussion

Two unresolved major questions were presented in the introduction. The first was the question of which temporal aspects of the MEG signal are predictive of conscious face perception.

M170 and P2m predict conscious face perception

Multivariate classification on binocular rivalry data demonstrated that activity around the face-specific M170 and P2m components differed on a single trial basis depending on whether a face was perceived consciously or not. Perception was predicted significantly better than chance from temporal sensors showing large average activity differences, and around these sensors group-level decoding accuracy was dependent on the single best sensor used. Additionally, perception could be decoded as well or better when using occipital sensors that showed little or no mean activity differences between conscious perception of a face or not. At these locations perception was predicted as accurately when using sensors that were individually at chance as when using all temporal sensors, thus showing a difference that was not revealed by univariate analyses. No predictive components were found after 300ms, thus arguing against activity at these times predicting conscious experience.

Interestingly, the event-related signal related to conscious face perception found in the masking study using identical durations for “seen” and “unseen” trials (Babiloni et al., 2010) appeared more similar to that found in the present experiment than to those found in other EEG masking experiments. This indicates that when physical stimulation is controlled for, very similar correlates of conscious face perception are found across paradigms. In neither experiment were differences found between late components (in fact, no clear late components are found).

MEG/EEG sensor and source correlates of visual consciousness

Our findings appear to generalize to not only to conscious face perception across paradigms, but also to visual awareness more generally. For example, Koivisto and Revonsuo (2010) reviewed around 40 EEG studies using different experimental paradigms and found that visual awareness correlated with posterior amplitude shifts around 130-320ms, also known as visual awareness negativity (VAN), whereas later components did not correlate directly with awareness. Furthermore, they argued that the earliest and most consistent ERP correlate of visual awareness is an amplitude shift around 200ms, corresponding well with the findings of the present study.

Nevertheless, other studies have argued that components in the later part of the VAN around 270ms (corresponding to the P2m of the present study) correlate more consistently with awareness, and that the fronto-parietal network is involved at this stage and later (Del Cul, Baillet, & Dehaene, 2007; Sergent, Baillet, & Dehaene, 2005). In the present study, the same frontal and parietal sources were identified, but little or no difference was found in the source estimates at the M170 and the P2m, and in fact, the frontoparietal sources were identified already at the M170. At both the M170 and the P2m, however, occipital and later face-specific source activity was more predictive than frontal and parietal activity, and early activity (around the M170) was much more predictive than late activity (>300ms). One reason for the difference in findings, however, could be that these studies Del Cul et al. and Sergent et al. examined having any experience versus having none (i.e. seeing versus not seeing) whereas our study examined one conscious content versus another (but participants perceived something consciously on all trials.

Overall, the present study appears to support the conclusion that the most consistent correlate of the contents of visual awareness is activity in sensory areas at around 150-200ms after stimulus onset. Prediction of conscious perception was no more accurate when taking information across multiple time points (and peaks) into account, than when training/testing the classifier on the single best time point.

Between-subject classification

The second question of our study was whether the conscious experience of an individual could be decoded using a classifier trained on a different individual. It is important to note that between-subject classifications of this kind do not reveal neural correlates of consciousness that generally distinguish a conscious from an unconscious state, or whether a particular, single content is consciously perceived or not, but they do allow us to make comparisons between the neural correlates of particular types of conscious contents (here, faces) across individuals.

The data showed that neural signals associated with specific contents of consciousness shared sufficient common features across participants to enable generalization of performance of the classifier. In other words, we provide empirical evidence that the neural activity distinguishing particular conscious content shares important temporal and spatial features across individuals, which implies that the crucial differences in processing are located at similar stages of visual processing across individuals. Nevertheless, generalization between individuals was not perfect, indicating that there are important inter-individual differences. Inspecting Fig. 3, for instance, it can be seen that the predictive time points around the M170 varied with up to 40ms between participants (from ~170ms for S3 to ~210ms for S2). At present, it is difficult to conclude whether these differences in the neural correlates indicate that the same perceptual content can be realized differently in different individuals or whether they indicate subtle differences in the perceptual experiences of the participants.

Methodological decisions

The results of the present experiment were obtained by analyzing the MEG signal during binocular rivalry. MEG signals during binocular rivalry reflect ongoing patterns of distributed synchronous brain activity that correlate with spontaneous changes in perceptual dominance during rivalry (Cosmelli et al., 2004). In order to detect these signals associated with perceptual dominance, the vast majority of previous studies have ‘tagged’ monocular images by flickering them at a particular frequency that can subsequently be detected in the MEG signals (e.g. Brown & Norcia, 1997; Kamphuisen, Bauer, & van Ee, 2008; Lansing, 1964; Srinivasan, Russell, Edelman, & Tononi, 1999). This method, however, impacts on rivalry mechanisms (Sandberg, Bahrami, Lindelov, Overgaard, & Rees, 2011) and causes a sustained frequency-specific response, thus removing the temporal information in the ERF components associated with normal stimulus processing. This not only biases the findings, but also makes comparison between rivalry and other paradigms difficult. To avoid this, yet maintain a high SNR, we exploited the stabilization of rivalrous perception associated with intermittent presentation (Leopold et al., 2002; Noest et al., 2007; Orbach, Ehrlich, & Heath, 1963) to evoke signals associated with a specific (stable) percept and time locked to stimulus onset. Such signals proved sufficient to decode spontaneous fluctuations in perceptual dominance in near real-time and in advance of behavioral reports. We suggest that this general presentation method may be used in future ambiguous perception experiments when examining stimulus-related differences in neural processing.

Potential confounds

There were two potential confounds in our classification analysis: eye movements and motor responses. These are, however, unlikely to have impacted on the results as source analysis revealed that at the time of maximum classification, sources related to visual processing were most important for explaining the differences related to face and grating perception. Additionally, the fact that the motor response used to signal a perceptual state was swapped between hands and fingers every 20 trials makes it unlikely that motor responses were assigned high weights by the classification algorithm. Nevertheless, our findings of prediction accuracy slightly greater than chance for power in high frequency bands may conceivably have been confounded by some types of eye movements.

Although we may conclude that specific evoked activity (localized and distributed) is related to conscious experience, this should not be taken as an indication that induced oscillatory components are not important for conscious processing. Local field potentials, for instance, in a variety of frequency bands are modulated in monkeys by perception during binocular rivalry (Wilke, Logothetis, & Leopold, 2006).

Apart from potential confounds in the classification analyses, it could be argued that the use of rotating stimuli is alters the stimulus-specific components. The purpose of rotating the stimuli in opposite directions was to minimize the amount of mixed perception throughout the trial (Haynes & Rees, 2005). It is possible, and remains a topic for further inquiries, whether this manipulation affects the mechanisms of the rivalry process, for instance in terms of stabilization of perception. Inspecting the ERF in Fig. 2, it is nevertheless clear that we observed the same face-specific components as are typically found in studies of face perception as reported above. Our M170 was observed slightly later than typically found (peaking at 187ms). This has previously been observed for partially occluded stimuli (A. M. Harris & Aguirre, 2008), and the delay in the present study might thus be due to binocular rivalry in general, or rotation of the stimuli. The impact of rotating the stimuli upon face-specific components thus appears minimal.

Conclusion

In the present study, participants viewed binocular rivalry between a face and a grating stimulus, and prediction of conscious face perception was attempted based on the MEG signal. Perception was decoded accurately in the 120-300ms time window, peaking around the M170 and again around the P2m. In contrast, little or no above-chance accuracy was found around the earlier M100 component. The findings thus argue against earlier and later components correlating with conscious face perception.

Additionally, conscious perception could be decoded from sensors that were individually at chance performance for decoding, whereas this was not the case when decoding using multiple time points. The most informative sensors were located above the occipital and temporal lobes, and a follow-up analysis of activity reconstructed at the source level revealed that the most predictive single sources were indeed found in these areas both at the M170 and the P2m. Nevertheless, conscious perception could be decoded accurately from parietal and frontal sources alone, although not as accurately as from occipital and later ventral stream sources. These results show that conscious perception can be decoded across a wide range of sources, but the most consistent correlates are found both at early and late stages of the visual system.

The impact of increasing the number of temporal features of the classifier was also examined. In contrast to including more spatial features, more temporal features had little or no impact on classification accuracy. Furthermore, the predictive strength of power estimation was examined across a wide range of frequency bands. Generally, the low frequencies contained in the evoked response were the most predictive, and the peak time points of classification accuracy coincided with the latencies of the M170 and the P2m. This indicates that the main MEG correlates of conscious face perception are the two face-sensitive components, the M70 and the P2m.

Finally, the results showed that conscious perception of each participant could be decoded above chance using classifiers trained on the data of each of the other participants. This indicates that the correlates of conscious perception (in this case, faces) are shared to some extent between individuals. It should be noted, though, that generalization was far from perfect, indicating that there are significant differences as well for further exploration.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (GR and GRB), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (RK), the European Commission under the Sixth Framework Programme (BB, KS, MO), Danish National Research Foundation and the Danish Research Council for Culture and Communication (BB), and the European Research Council (KS and MO). Support from the MINDLab UNIK initiative at Aarhus University was funded by the Danish Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation.

Appendix

Improving decoding accuracy

We hypothesized that decoding accuracy could be increased in two ways: by rejecting trials for which perception was not completely clear, and by applying a more stringent filter to the data. Participant’s reports (see Results, above) suggested that the probability of clear perception on a given trial increased the further away the trial is from a perceptual switch. Classifiers were thus trained and tested on unstable perception (trials 1-9 after a switch) and stable perception (trial 10 or more after a switch) separately and decoding accuracies were compared. 5 participants reported 100 trials of all kinds (stable/unstable faces/gratings) required for training the classifier, and the analysis was thus based on these. Fig. A1a shows that analyzing using stable trials as compared to unstable trials results in a large improvement in classification accuracy of around 10-15% around the M170 (~187ms), 5-8% around the P2m (~260ms), and similarly 5-8% around the M100 (~93ms). Significant improvements in classification accuracy was found for at least 3 out of 5 participants for all components (cumulative p=0.0012, uncorrected).

Some components analyzed (M100, M170 and P2m) had a temporal spread of around 50-130ms (see Fig. A1a-c), yet the classifiers were trained on single time points only in the analyses above. This makes classification accuracy potentially vulnerable to minor fluctuations at single time points. Such fluctuations could reflect small differences in latency between trials as well as artifacts and high-frequency processes that the classifier cannot exploit, and analyses based on field strength data may thus be improved if the impact of these high-frequency components and trial-by-trial variation is minimized. There are two methods to do this: classification may either use several neighboring time points, or a low low-pass filter may be applied before analysis to temporally smooth the data.

Given the temporal extent of the three analyzed components (50-130ms), they can be seen as half-cycles of waves with frequencies of 4-10Hz (i.e. around 100-250ms). For this reason, we compared classification accuracies for non-filtered data, 1-20Hz filtered data, and 2-10Hz filtered data. We used only stable trials. Six participants had 100 stable trials or more of each kind (face/grating) and were thus included in the analysis.

Fig. A1b shows the differences between the three filter conditions for within-subject decoding. Improvement in decoding accuracy was found comparing no filter and the filtered data. Comparing unfiltered and 1-20Hz filtered data at the M170 and P2m, differences of 5-10% were found around both peaks, and around the M100 a difference of around 5% was found. Decoding accuracy was significantly higher for 5 out of 6 participants at the 187ms (cumulative probability of p=1.9*10−6, uncorrected), and for 4 out of 6 participants at 260ms (cumulative probability of p=8.7*10−5, uncorrected), but only for 2 out of 6 participants at 90ms (cumulative probability of p=0.03, uncorrected). The largest improvement of applying a 20Hz low-pass filter was thus seen for the two most predictive components, the M170 and the P2m. The only impact of applying a 2-10Hz filter instead of a 1-20Hz filter was significantly increased accuracy for 2 participants at 187ms, but decreased for 1.

As between-subject ERF variation is much larger than within-subject variation (Sarnthein, Andersson, Zimmermann, & Zumsteg, 2009), we might expect that the most stringent filter mainly improved between-subject decoding accuracy. Fig. A1c shows a 2-3% improvement of using a 2-10Hz compared to a 1-20Hz filter at the M170 and the P2m, and a <1% improvement at the M100. This improvement was significant for 2 participants at the 180ms and 260ms (cumulative p=0.03, uncorrected, for both, and 1 participant around the M100 at 117ms (cumulative p=0.27, uncorrected).

Overall, the best decoding accuracies were achieved using stable trials and filtered data. Numerically better and slightly more significant results were achieved using 2-10Hz filtered data compared to 1-20Hz filtered data. Importantly, using this more stringent filter did not alter the time points for which conscious perception could be decoded – it only improved accuracy around the peaks.

Decoding using power estimations

Power in several frequency bands (for all sensors) was also used to train SVM classifiers. This analysis revealed that theta band power was the most highly predictive of perception followed by alpha power (Fig. A2). Again the data were the most informative at around 120-320ms after stimulus onset. Power estimates in the higher frequency bands related to both face and grating perception (40-60Hz) and possibly also some related to face perception alone (60-80Hz) could be used to predict perception significantly better than chance (Duncan et al., 2010; Engell & McCarthy, 2010). In these bands, the prediction accuracy did not have any clear peaks (Fig. A2).

Using Bonferroni correction, average prediction accuracies across participants across the stimulation period were above chance in the theta (t(7)=4.4, p=0.033), gamma2 (40-49Hz) (t(7)=4.9, p=0.017), and gamma3 (51-60Hz) (t(7)=4.2, p=0.038) bands. Without Bonferroni correction, alpha (t(7)=3.2, p=0.0151), low beta (t(7)=3.7, p=0.0072), high beta (t(7)=3.1, p=0.0163), gamma4 (61-70Hz) (t(7)=3.3, p=0.0123), and gamma5 (71-80Hz) (t(7)=2.4, p=0.0466) were also above chance.

The classification performance based on the moving window spectral estimate was always lower than that based on the field strength. Also, spectral classification was optimal for temporal frequencies dominating the average evoked response (inspecting Fig. 2B-C, it can be seen, for instance, that for faces, the M170 is half a cycle of a 3-4Hz oscillation). Taken together, this suggests that the predictive information was largely contained in the evoked (i.e. with consistent phase over trials) portion of the single trial data.

Decoding using multiple time points

The potential benefit of including multiple time points when training classifiers was examined. As multiple time points increase the number of features drastically, the SVM was trained on a subset of sensors only. For these analyses, 16 randomly selected sensors giving a performance of 72.6% when trained on a single time point were used (see Fig. 4A). As the temporal smoothing of low-pass filter would theoretically remove any potential benefit of using multiple time points for time intervals shorter than one cycle of activity, these analyses were performed 1 Hz high-pass filtered data. Here, the sampling frequency of 300Hz is thus the maximum frequency.

We tested the impact of training on up to 11 time points (37ms) around each peak (M170 and P2m) and around a time point for which overall classification accuracy was at chance (50ms). At 50ms, the signal should have reached visual cortex, but a 37ms time window did not include time points with individual above-chance decoding accuracy. We also tested the combined information around the peaks. As seen in Fig. A3, the inclusion of more time points did not increase accuracy, and the use of both peaks did not increase accuracy beyond that obtained at the M170 alone. This may indicate that the contents of consciousness (in this case rivalry between face and grating perception), is determined already around 180ms.

Figure A1. Improvements to prediction accuracy by filtering and trial selection.

The figure plots the impact of using stable trials only as well as filtering the data. Dotted gray line represents the 95% binomial confidence interval around chance (uncorrected). A) Prediction accuracy for stable and unstable trials respectively. The comparison is based on the 5 participants who reported enough trials of all conditions (stable/unstable faces/gratings) to train the classifiers. B-C) Within-subject (B) and between-subject (C) prediction accuracy for data that has not been low-pass filtered compared to data low-pass filtered at 20 and 10Hz respectively. This analysis was based on stable trials, and the data reported are from the analysis of the six participants reporting enough stable face and grating trials to train the classifier.

Figure A2. Prediction accuracy across time for various frequencies (stable trials).

6 participants had enough trials to train the classifiers on stable trials alone. The figure plots the data from these participants. The dotted gray line indicates the threshold for which a binomial distribution of the same number as the total number of trials the prediction is performed upon is different from chance (uncorrected). Average prediction accuracy is plotted across participants based on estimates of power in different frequency bands as a function of time. Support vector machines were trained to predict reported perception (face vs. grating) for each time point.

Figure A3. Prediction based on multiple time points (stable trials).

Six participants had enough trials to train the classifiers on stable trials alone. The figure plots the data from these participants. Classifiers were trained/tested on 1Hz high-pass filtered data from 16 randomly distributed sensors. A-C) Prediction accuracy as a function of the number of neighboring time samples used to train the classifier around the M170 peak (A), the P2m peak (B), and 50ms after stimulus onset (C). No improvement was found at the peaks nor at 50ms when classifier baseline accuracy was close to chance. D) Prediction accuracy when classifiers were trained on data around both peaks combined vs. each peak individually.

References

- Babiloni C, Vecchio F, Buffo P, Buttiglione M, Cibelli G, Rossini PM. Cortical responses to consciousness of schematic emotional facial expressions: A high-resolution EEG study. Human Brain Mapping. 2010;31(10):1556–1569. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20958. doi:10.1002/hbm.20958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake R. A Primer on Binocular Rivalry, Including Current Controversies. Brain and mind. 2001;2:5–38. [Google Scholar]

- Brascamp JW, Knapen THJ, Kanai R, Noest AJ, Van Ee R, Van den Berg AV, He S. Multi-Timescale Perceptual History Resolves Visual Ambiguity. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(1):e1497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001497. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese BB. On inhibition. Psychological Monographs. 1899;3:1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RJ, Norcia AM. A method for investigating binocular rivalry in real-time with the steady-state VEP. Vision Research. 1997;37(17):2401–2408. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson TA, Hogendoorn H, Kanai R, Mesik J, Turret J. High temporal resolution decoding of object position and category. Journal of Vision. 2011;11(10):9–9. doi: 10.1167/11.10.9. doi:10.1167/11.10.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter O, Cavanagh P. Onset rivalry: brief presentation isolates an early independent phase of perceptual competition. PloS One. 2007;2(4):e343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmelli D, David O, Lachaux J-P, Martinerie J, Garnero L, Renault B, Varela F. Waves of consciousness: ongoing cortical patterns during binocular rivalry. NeuroImage. 2004;23(1):128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.05.008. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Cul A, Baillet S, Dehaene S. Brain dynamics underlying the nonlinear threshold for access to consciousness. PLoS biology. 2007;5(10):e260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050260. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan KK, Hadjipapas A, Li S, Kourtzi Z, Bagshaw A, Barnes G. Identifying spatially overlapping local cortical networks with MEG. Human Brain Mapping. 2010;31(7):1003–1016. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20912. doi:10.1002/hbm.20912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engell AD, McCarthy G. Selective attention modulates face-specific induced gamma oscillations recorded from ventral occipitotemporal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(26):8780–8786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1575-10.2010. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1575-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman AW. Multistage model for binocular rivalry. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2005;94(6):4412–4420. doi: 10.1152/jn.00557.2005. doi:10.1152/jn.00557.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Harrison L, Daunizeau J, Kiebel S, Phillips C, Trujillo-Barreto N, Mattout J. Multiple sparse priors for the M/EEG inverse problem. NeuroImage. 2008;39(3):1104–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.048. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AM, Aguirre GK. The effects of parts, wholes, and familiarity on face-selective responses in MEG. Journal of Vision. 2008;8(10):4.1–12. doi: 10.1167/8.10.4. doi:10.1167/8.10.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Wu C-T, Woldorff MG. Sandwich masking eliminates both visual awareness of faces and face-specific brain activity through a feedforward mechanism. Journal of Vision. 2011;11(7):3–3. doi: 10.1167/11.7.3. doi:10.1167/11.7.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby Hoffman, Gobbini The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4(6):223–233. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes J-D, Deichmann R, Rees G. Eye-specific effects of binocular rivalry in the human lateral geniculate nucleus. Nature. 2005;438(7067):496–499. doi: 10.1038/nature04169. doi:10.1038/nature04169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes J-D, Rees G. Predicting the stream of consciousness from activity in human visual cortex. Current Biology: CB. 2005;15(14):1301–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.026. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuisen A, Bauer M, Van Ee R. No evidence for widespread synchronized networks in binocular rivalry: MEG frequency tagging entrains primarily early visual cortex. Journal of Vision. 2008;8(5):4.1–8. doi: 10.1167/8.5.4. doi:10.1167/8.5.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto M, Revonsuo A. Event-related brain potential correlates of visual awareness. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34(6):922–934. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.12.002. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornmeier J, Bach M. Early neural activity in Necker-cube reversal: evidence for low-level processing of a gestalt phenomenon. Psychophysiology. 2004;41(1):1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8986.2003.00126.x. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8986.2003.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansing RW. Electroencephalographic correlates of binocular rivalry in man. Science. 1964;146:1325–1327. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3649.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold DA, Wilke M, Maier A, Logothetis NK. Stable perception of visually ambiguous patterns. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5(6):605–609. doi: 10.1038/nn0602-851. doi:10.1038/nn851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell BJ, Williams LM, Rathjen J, Shevrin H, Gordon E. A Temporal Dissociation of Subliminal versus Supraliminal Fear Perception: An Event-related Potential Study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16:479–486. doi: 10.1162/089892904322926809. doi:10.1162/089892904322926809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumer ED, Friston KJ, Rees G. Neural correlates of perceptual rivalry in the human brain. Science. 1998;280(5371):1930–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noest, Van Ee R, Nijs MM, Van Wezel RJ. Percept-choice sequences driven by interrupted ambiguous stimuli: A low-level neural model. Journal of Vision. 2007;7(8):10. doi: 10.1167/7.8.10. doi:10.1167/7.8.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orbach J, Ehrlich D, Heath H. Reversibility of the Necker cube: I. An examination of the concept of ‘satiation of orientation’. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1963;17:439–458. doi: 10.2466/pms.1963.17.2.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegna AJ, Darque A, Berrut C, Khateb A. Early ERP Modulation for Task-Irrelevant Subliminal Faces. Frontiers in Psychology. 2011;2 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00088. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegna AJ, Landis T, Khateb A. Electrophysiological evidence for early non-conscious processing of fearful facial expressions. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2008;70(2):127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.08.007. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizada RDS, Connolly AC. What Makes Different People’s Representations Alike: Neural Similarity Space Solves the Problem of Across-subject fMRI Decoding. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00189. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg K, Bahrami B, Lindelov JK, Overgaard M, Rees G. The impact of stimulus complexity and frequency swapping on stabilization of binocular rivalry. Journal of Vision. 2011;11(2):6. doi: 10.1167/11.2.6. doi:10.1167/11.2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg K, Barnes G, Bahrami B, Kanai R, Overgaard M, Rees G. MEG correlates of stabilization of binocular rivalry. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.023. in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnthein J, Andersson M, Zimmermann MB, Zumsteg D. High test-retest reliability of checkerboard reversal visual evoked potentials (VEP) over 8 months. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2009;120(10):1835–1840. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.014. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergent C, Baillet S, Dehaene S. Timing of the brain events underlying access to consciousness during the attentional blink. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8(10):1391–1400. doi: 10.1038/nn1549. doi:10.1038/nn1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Russell DP, Edelman GM, Tononi G. Increased synchronization of neuromagnetic responses during conscious perception. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19(13):5435–5448. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05435.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke M, Logothetis NK, Leopold DA. Local field potential reflects perceptual suppression in monkey visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(46):17507–17512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604673103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604673103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HR. Computational evidence for a rivalry hierarchy in vision. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(24):14499–14503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2333622100. doi:10.1073/pnas.2333622100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HR. Minimal physiological conditions for binocular rivalry and rivalry memory. Vision Research. 2007;47(21):2741–2750. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.07.007. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]