Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease without known ways to cure. A key neuropathologic manifestation of the disease is extracellular deposition of beta-amyloid peptide (Aβ). Specific mechanisms underlying the development of the disease have not yet been fully understood. In this study, we investigated effects of 4-O-methylhonokiol on memory dysfunction in APP/PS1 double transgenic mice. 4-O-methylhonokiol (1 mg/kg for 3 month) significantly reduced deficit in learning and memory of the transgenic mice, as determined by the Morris water maze test and step-through passive avoidance test. Our biochemical analysis suggested that 4-O-methylhonokiol ameliorated Aβ accumulation in the cortex and hippocampus via reduction in beta-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 expression. In addition, 4-O-methylhonokiol attenuated lipid peroxidation and elevated glutathione peroxidase activity in the double transgenic mice brains. Thus, suppressive effects of 4-O-methylhonokiol on Aβ generation and oxidative stress in the brains of transgenic mice may be responsible for the enhancement in cognitive function. These results suggest that the natural compound has potential to intervene memory deficit and progressive neurodegeneration in AD patients.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, 4-O-methylhonokiol, APP/PS1 double transgenic, Antioxidant, Beta-site APP-cleaving enzyme

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease and a significant cause of mortality and morbidity among elderly people. A prime neuropathologic manifestation of the neurodegenerative disease is extracellular deposition of amyloid-beta (Aβ) (Hardy and Allsop, 1991). Aβ is produced from amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretases through their sequential proteolytic actions (Hardy and Allsop, 1991). Beta-site APP-cleaving enzyme (BACE) 1 cleaves APP to form Aβ N-terminus, APPβ and a C-terminal fragment, C99 and γ-secretase subsequently generates Aβs with two variants, Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42. Presenilins (PSs) have been identified to be associated with γ-secretase in vivo and in vitro (Kimberly et al., 2000). PS1 knockout mice showed markedly reduced γ-secretase cleavage of APP (De Strooper et al., 1998). In addition, knockout of both PS1 and PS2 completely abolished γ-secretase activity (Herreman et al., 2000).

Several mutations in the APP and presenilin 1 and 2 (PS1, PS2) genes were found to be linked to familial form of AD (Price and Sisodia, 1998). These mutations are associated with alterations of APP processing with enhancement of Aβ1–42 production (Octave et al., 2000). Trangsgenic mice that overexpress mutant APP showed Aβ amyloid deposition in the brain (Hsiao et al., 1996), and occurrence of Aβ amyloid plaques became earlier when they were crossed with mutant PS1 transgenics (Borchelt et al., 1997, McGowan et al., 1999).

Compounds from Magnolia species have exhibited various pharmacological activity such as antimicrobial (Ho et al., 2001), anxiolytic (Seo et al., 2007), neurotrophic (Lee et al., 2009) and cholinergic (Matsui et al., 2009) effects. To define these effects, researchers isolated many bioactive components such as honokiol, obovatol, magnolol and 4-O-methylhonokiol. In previous studies, we showed that 4-O-methylhonokiol ameliorated memory impairment in several different animal models including a systemic LPS-induced dementia model (Lee et al., 2012a), presenilin 2 mutant transgenic mice (Lee et al., 2011) and Tg2576 mice (Lee et al., 2012b). Another compound from Magnolia species, obovatol potently blocked Aβ aggregation (Choi et al., 2012a) and enhanced learning and memory in Tg2576 mice by blocking neuroinflammatory responses and Aβ formation (Choi et al., 2012a).

In the present study, we investigated whether administration of 4-O-methylhonokiol could attenuate cognitive dysfunction in mice expressing the mutant APP (K670N, M671L) and the mutant PS1 (M146L). Here, we shows 4-O-methylhonokiol significantly ameliorates memory deficit and pathologic Aβ deposition in the animals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of 4-O-methylhonokiol

4-O-methylhonokiol was isolated from the bark of Magnolia officinalis according to previous description (Lee et al., 2009). Briefly, the air-dried bark of Magnolia officinalis (3 kg) was cut into small pieces and extracted with 95% (v/v) ethanol for 3 days at room temperature. After filtration through the 400-mesh filter cloth, the filtrate was re-filtered through filter paper (Whatman, No. 5) and concentrated under reduced pressure. The extract (450 g) was then suspended in distilled water, and the aqueous suspension was extracted with n-hexane, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol, respectively. The n-hexane layer was evaporated to dry, and the residue (70 g) was chromatographed on silica gel with n-hexane:ethyl acetate (9:1) solution to extract a crude fraction that included 4-O-methylhonokiol. This fraction was repeatedly purified by silica gel chromatography using n-hexane:ethyl acetate as the eluent to obtain pure 4-O-methylhonokiol. The purity was identified to be more than 99.5%.

Animals and treatment

Male double transgenic APP/PS1 mice expressing human amyloid precursor protein (HuAPP695swe) and a mutant human presenilin 1 (PS1-dE9) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and backcrossed with female C57Bl/6 mice to generate double transgenic and nontransgenic littermates. The animals were maintained in accordance with the Korea Food and Drug Administration guideline for the humane care and use of laboratory animals. All of the experimental procedures in this study were approved by IACUC of Chungbuk National University (approval number: CBNUA-144-1001-01). Animals were housed in a room that was automatically maintained at 21–25°C and relative humidity (45–65%) with a controlled light-dark cycle. The mice were under free access to food and water. 5 month old male APP/PS1 mice were treated with either 4-O-methylhonokiol (1 mg/kg, n=10) or vehicle (0.5% ethanol, n=10) for 3 months.

The Morris water maze test

The Morris water maze test was performed as described in the previous studies with minimal modification (Choi et al., 2012a; Choi et al., 2012b). Briefly, mice were placed in the pool and allowed to swim freely. Swimming traces of animals were recorded until they reached to the hidden platform and the time length was defined as latency. Each trial lasted for 60 seconds or ended as soon as the mouse reached the submerged platform and was allowed to remain on the platform for 10 seconds. Escape latency, escape distance, swimming speed, and swimming pattern of each mouse were monitored by a camera above the center of the pool connected to a SMART-LD program (Panlab, Barcelona, Spain). A quiet environment, consistent lighting, constant water temperature, and fixed spatial frame were maintained throughout the period of the experiment. Test trial was performed for 8 days after the last training trial. A probe trial to assess memory consolidation was performed 24 hrs after the 8-day acquisition tests. In this trial, the platform was removed from the tank, and the mice were allowed to swim freely. For these tests, percentage of time in the target quadrant and target site crossings within 60 seconds was recorded. The time spent in the target quadrant was taken to indicate the degree of memory consolidation that had taken place after learning.

Passive avoidance test

Mice were subject to passive avoidance test 24 hrs after the Morris water maze test as described previously (Choi et al., 2012a; Choi et al., 2012b). Briefly, for the training trial, individual animal was placed in the light compartment. When the animal entered the dark chamber, the door was closed and an electrical foot shock (0.4 mA) with 2 second-long duration was delivered through the stainless steel rods. The test trial was conducted 24 hrs after training trial. Latency was defined as time mice spent before enter the dark compartment. Maximum latency was set to 600 seconds.

Immunohistochemistry

After behavioral tests, 5 out of 10 animals were intracardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS under the deep anesthesia (Na pentobarbital, 100 mg/kg). After perfusion, the brains were removed from the skull and post-fixed for 24 hr in the same fixative at 4°C, and were then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose prepared in phosphate buffer. Serial coronal sections of brain (30 μm) were cut with a freezing slide microtome (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with antibody to Aβ1–42 (1:2000, Covance, Berkeley, CA, USA) or 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) (1:2000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). After multiple washings in PBS, the sections were incubated in biotinylated IgG (1:1000, Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, California, USA) for 1 hr at room temperature. The sections were subsequently washed and incubated with avidin-conjugated peroxidase complex (ABC kit, Vector Laboratories Inc.) for 60 min. The immunocomplex was visualized by using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich Korea, Seoul, Korea) as the chromogen. Finally, the brain sections were rinsed and mounted on poly-glycine-coated slides and analyzed under the light microscopy.

Western blot

Animals were sacrificed after behavioral tests and five half brains were subject to the Western blot analysis. The analysis was performed as described previously with slight modification (Choi et al., 2012a). Briefly, equal amount of proteins (30 μg) were electrophoresed on a 10 or 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Hybond ECL, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, NJ, USA). Blots were blocked for 2 hr at room temperature in 5% (w/v) non-fat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline [10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl] containing 0.05% tween-20. The membrane was then incubated for 1 hr at room temperature with specific primary antibody against APP (1:500, ABR-affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO, USA), BACE1 (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich), Aβ1–42 (B-4) (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), 4-HNE (1:000, Abcam) or β-actin (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich Korea). The blots were then incubated in the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated immunoglobulin G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). Immunoreactive protein was detected with the ECL western blot detection system. We used Super Signal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher scientific) to detect Aβ. The relative density of the protein bands was quantified by densitometry using Electrophoresis Documentation and Analysis System 120 (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY, USA).

Assay for glutathione peroxidase activity

Five half brains were used to assay glutathione peroxidase activity. Brain tissue was sonicated in PBS for 15 seconds on ice and the homogenate was subject to centrifugation at 1,000 ×g at 4°C for 5 min to obtain supernatant. The supernatant was used in glutathione peroxidase assay. Briefly, the GSSG produced during the glutathione peroxidase enzyme reaction is immediately reduced by glutathione reductase and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). Therefore, the rate of NADPH consumption (monitored as a decrease in absorbance at 340 nm) is proportional to formation of GSSG during the glutathione peroxidase reaction. The reaction buffer contained 20 mM potassium phosphate, (pH 7.0), 0.6 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.15 mM NADPH, 4 units of glutathione reductase, 2 mM GSH, 1 mM sodium azide, and 0.1 mM H2O2. This assay was performed at 25°C. 1 unit of glutathione peroxidase activity is defined 1 μmol NADPH consumed per minute.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4 software (Version 4.03, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Difference between groups was assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc Dunnet’s test. When a value of p is less than 0.05, it was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

4-O-methylhonokiol-mediated cognitive improvement in transgenic mice

We determined learning ability by carrying out the Morris water maze test. The animals were trained for 3 days (twice/ day) prior to test trials, and their learning for location of hidden platform was examined daily for 8 days. Cognitive function was rated by distance and time that animals took till they located to the platform. Treatment of 4-O-methylhonokiol or vehicle did not show any significant effects on the swimming speed during the tests (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the escape latency was gradually decreased in training sessions with significant difference between vehicle-treated and 4-O-methylhonokiol-treated groups (Fig. 1A). The compound administration significantly decreased the escape latency and distance compared with vehicle treatment at test trials. At day 8, there was no significant difference in latency between vehicle-treated and the compound-treated mice. Probe test confirmed that memory retention was significantly consolidated only in 4-O-methylhonokiol-administered animals (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

4-O-methylhonokiol ameliorates memory impairments in APP/PS1 double transgenic mice. Animals were treated with the natural compound for 3 months and the Morris water maze and passive avoidance tests were performed. With the Morris water maze test, 4-O-methylhonokiol appears to enhance cognitive function of the double transgenic mice (A). There is no significant difference between vehicle-treated animals and the compound-treated animals. The memory consolidation is shown to be better in 4-O-methylhonokiol-treated animals as determined by probe test (B). The step-through passive avoidance memory test reveals that the compound improves contextual memory in the transgenic mice (C). Values are presented as mean ± SD from 10 mice. *p<0.05 vs. vehicle treatment. MH=4-O-methylhonokiol.

To determine 4-O-methylhonokiol-induced improvement of the contextual memory in the transgenic mice, we performed step-through passive avoidance tests. Vehicle-treated animals did not show significant memory retention as performance on test trial was not statistically different from that on training sessions, suggesting that the transgenic mice had a cognitive dysfunction (Fig. 1C). In contrast, there was significant memory retention in 4-O-methylhonokiol-administered animals. In addition, the result showed that the treatment significantly attenuated the memory deficit when it was compared with vehicle-treated control (Fig. 1C).

4-O-methylhonokiol-mediated amelioration in Aβ generation in transgenic mice

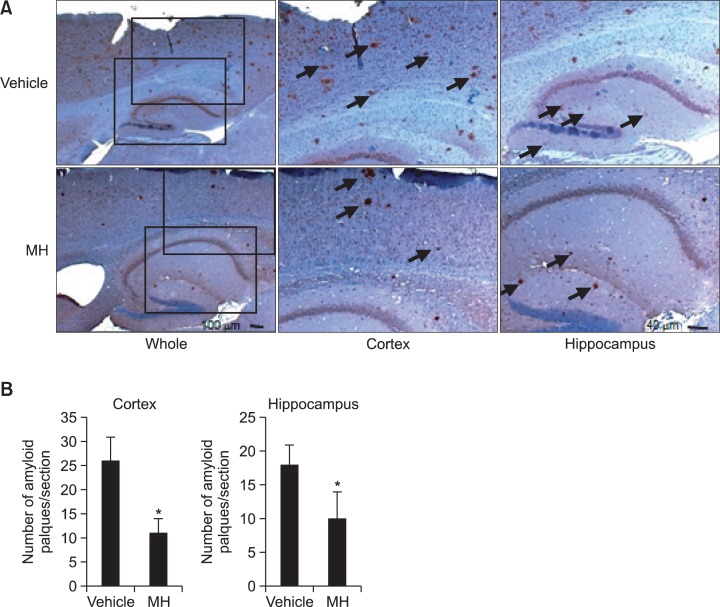

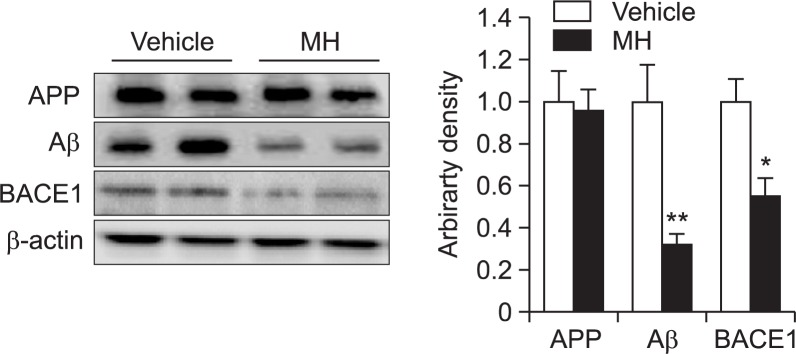

We assessed effects of 4-O-methylhonokiol on Aβ formation in the transgenic animals using western blot and immunohistochemical analysis. Immunostaining for Aβ clearly showed that Aβ was accumulated in the cortex and hippocampus of the animals (Fig. 2). Aβ-positive plaques were observed throughout the cortex and hippocampus areas both in vehicle-treated and 4-O-methylhonokiol-treated mice. However, long-term treatment of 4-O-methylhonokiol significantly attenuated Aβ deposition in the brain areas as shown by immunohisto-chemistry (Fig. 2). To clarify how Aβ deposition was attenuated by the natural compound, we analyzed levels of APP, Aβ and BACE1 in the brain. Our data showed that 4-O-methylhonokiol treatment significantly reduced expression of BACE1, while APP production was not affected by the treatment (Fig. 3). Furthermore, administration of 4-O-methylhonokiol alleviated level of Aβ in the brain implying that reduced expression of BACE1 by the compound might be relevant to attenuated Aβ accumulation in the cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

4-O-methylhonokiol attenuates Aβ accumulation in the cortex and hippocampus of the double transgenic mice. Immunohistochemical analysis shows that Aβ is markedly deposited in the brains of the transgenic mice and long-term treatment of 4-O-methylhonokiol alleviates accumulation of the pathogenic peptide (A). Quantification of Aβ accumulation shows that 4-O-methylhonokiol significantly attenuates Aβ deposition both in the cortex and hippocampus (B). *p<0.05 vs. vehicle MH=4-O-methylhonokiol.

Fig. 3.

4-O-methylhonokiol suppresses BACE1 expression and Aβ generation. Western blot analysis shows that 4-O-methylhonokiol significantly decreases BACE1 expression in the brain. Aβ level is significantly lower in the 4-O-methylhonokiol-treated brains. Values are presented as mean ± SD from 5 independent blots. *p<0.05 vs. vehicle, **p<0.01 vs. vehicle. MH=4-O-methylhonokiol.

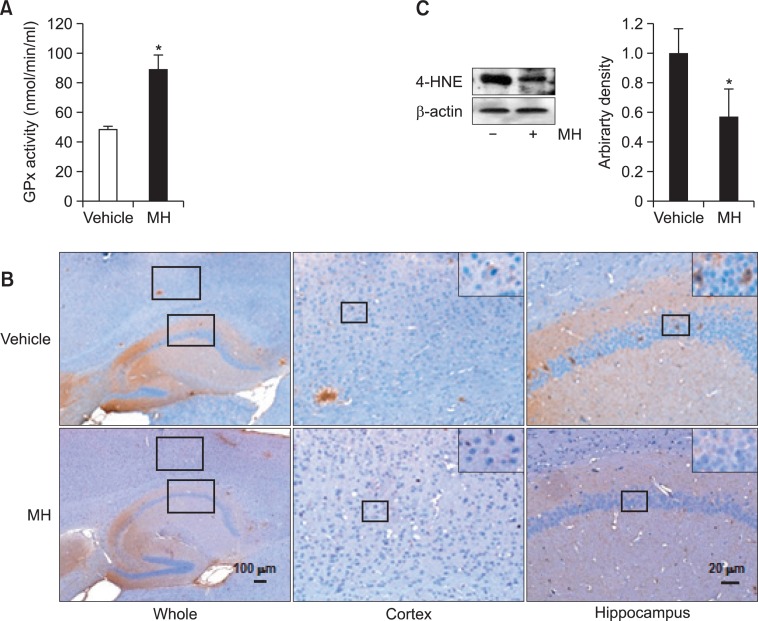

Attenuation in oxidative stress by 4-O-methylhonokiol

Finally, we assessed effects of 4-O-methylhonokiol on lipid peroxidation level in the brain, since previous study had shown that the compound improved the cognitive function through antioxidant properties (Choi et al., 2011). Our assessment revealed that the compound significantly elevated glutathione peroxidase activity (Fig. 4A). In addition, 4-O-methylhonokiol significantly suppressed lipid peroxidation in the transgenic brain as shown by immunostanings and western blot for 4-HNE (Fig. 4B). Thus, these results imply that the compound alleviated oxidative stress in the brains and this effect might be associated with protection from cognitive malfunction.

Fig. 4.

4-O-methylhonokiol increases antioxidant capacity and de creases lipid peroxidation. Long-term treatment of 4-O-methylhonokiol raises the activity of glutathione peroxidase in the brains (A). 4-HNE level is significantly lower in the 4-O-methylhonokiol as assessed by immunohistochemistry (B) and western blots (C). Values are presented as mean ± SD from 5 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs. vehicle, MH=4-O-methylhonokiol, GPx=glutathione peroxidase.

DISCUSSION

AD is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder pathologically characterized by extracellular deposition of Aβ and intracellular deposition of hyper-phosphorylated tau protein. Despite of significant advances in understanding molecular mechanisms by which neurons are degenerated in Alzheimer’s brains, the cause of the disease remains to be elucidated. Furthermore, there is no way to cure or slow down the neurodegeneration up to now. Because current approved medications have only limited or marginal efficacy on AD, development of a novel therapy for the disease is necessary. In this investigation, we clearly demonstrated that 4-O-methylhonokiol attenuated cognitive impairments in APP/PS1 double transgenic mice. Our results suggest that the improvement in cognitive function might come from decrease in Aβ generation via suppressing BACE1 expression. In addition, the beneficial effects of 4-O-methylhonokiol might be partially attributable to decrease in oxidative stress.

We observed that treatment of 4-O-methylhonokiol significantly attenuated deterioration in learning and memory, and this effect was coincided with reduction in Aβ deposition in the hippocampus and cortex. Aβ is derived from APP by sequential proteolytic actions of BACE1 and γ-secretase. BACE1 is necessary for initiation of Aβ generation and the enzyme expression is up-regulated in AD brains (Holsinger et al., 2002; Cole and Vassar, 2008). Activation of NF-κB upregulates expression of BACE1 and enhances Aβ formation (Sambamurti et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2012; Ai et al., 2013). Further support for the assumption comes from a report that the mutation on the NF-κB binding site of BACE1 promoter decreases the promoter activity resulting in reduced expression of BACE1 (Bourne et al., 2007). In previous studies, we demonstrated that 4-O-methylhonokiol suppressed DNA-binding activity of NF-κB and BACE1 expression in the brains of AD animal models, suggesting that the compound may reduce BACE1 level by way of blunting NF-κB signaling pathway (Lee et al., 2012a).

Accumulated evidence suggests that neuroinflammatory events are related to regulation of BACE1 expression (Sastre et al., 2008). Although we did not demonstrated anti-neuroinflammatory properties of 4-O-methylhonokiol in this investigation, previous studies revealed that this compound had a potent anti-neuroinflammatory activity which was associated with cognitive enhancement in the AD animal models (Lee et al., 2012a; Lee et al., 2013). We suggested that the anti-inflammatory activity was mediated by diminishing NF-κB signaling pathway. Recently, Schuehly et al showed that 4-O-methylhonokiol acts like a cannabinoid type 2 (CB2) receptor ligand (Schuehly et al., 2011). They suggest that effects of the compound on CB2 receptors are associated with anti-neuroinflammatory effects, since the receptors are primarily associated with a broad range of inflammatory processes (Gertsch and Anavi-Goffer, 2012). In general, CB2 receptors do not exist in the central nervous system under normal conditions, but are expressed in microglial cells and astrocytes upon neuro-inflammatory stimulation (Ashton and Glass, 2007). Overall, it seems that multiple action mechanisms of 4-O-methylhonokiol are involved in its anti-neuroinflammatory activity which might be responsible for downregulation of BACE1 expression.

Oxidative damage has been shown to induce β-secretase activity (Tamagno et al., 2002). Oxidative damage in brain tissue of sporadic AD patients was detected which was significantly correlated with β-secretase activity (Guglielmotto et al., 2010). In Tg2576 mice, deletion of 12/15-lipoxygenase decreased oxidative stress and amyloid formation via β-secretase downregulation (Yang et al., 2010). Furthermore, deficiency in cytochrome oxidase c in neurons significantly reduces both oxidative stress and amyloid genesis in an animal model for AD, which is related to lowered β-secretase activity (Fukui et al., 2007). Our previous study showed that 4-O-methylhonokiol suppressed oxidative stress in neurons with concurrent reduction in β-secretase activity (Choi et al., 2011). Consistent with previous studies, our results demonstrated that 4-O-methylhonokiol reduced oxidative stress as 4-HNE level was decreased in the brain. Additionally, 4-O-methylhonokiol mediated rise in glutathione peroxidase activity. These results suggest that reduction in BACE1 expression might be related to antioxidant effects of the natural compound.

In conclusion, this study showed that 4-O-methylhonokiol stabilized cognitive function in APP/PS1 double transgenic mice. Population of AD patients will be growing rapidly, because of increase in life expectancy and aging of baby boomer generation. Thus, development of new therapeutics for AD treatment is an urgent issue. Novel compounds from plant sources such as 4-O-methylhonokiol could be valuable alternatives in the context of the treatment of AD due to its therapeutic effects and safety.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the 2012 Yeungnam University Research Grant, and the National Research Foundation Grant funded by Korea government (MSIP) (MRC, 2008-0062275). We disclose that there is no any actual or potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ai J, Sun LH, Che H, Zhang R, Zhang TZ, Wu WC, Su XL, Chen X, Yang G, Li K, Wang N, Ban T, Bao YN, Guo F, Niu HF, Zhu YL, Zhu XY, Zhao SG, Yang BF. MicroRNA-195 protects against dementia induced by chronic brain hypoperfusion via its anti-amyloidogenic effect in rats. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3989–4001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1997-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton JC, Glass M. The cannabinoid CB2 receptor as a target for inflammation-dependent neurodegeneration. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2007;5:73–80. doi: 10.2174/157015907780866884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchelt DR, Ratovitski T, van Lare J, Lee MK, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Price DL, Sisodia SS. Accelerated amyloid deposition in the brains of transgenic mice coexpressing mutant presenilin 1 and amyloid precursor proteins. Neuron. 1997;19:939–945. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80974-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne KZ, Ferrari DC, Lange-Dohna C, Rossner S, Wood TG, Perez-Polo JR. Differential regulation of BACE1 promoter activity by nuclear factor-kappaB in neurons and glia upon exposure to beta-amyloid peptides. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1194–1204. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Zhou W, Liu S, Deng Y, Cai F, Tone M, Tone Y, Tong Y, Song W. Increased NF-kappaB signalling up-regulates BACE1 expressionand its therapeutic potential in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:77–90. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DY, Lee JW, Lin G, Lee YJ, Ban JO, Lee YH, Choi IS, Han SB, Jung JK, Lee WS, Lee SH, Kwon BM, Oh KW, Hong JT. Obovatol improves cognitive functions in animal models for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2012a;120:1048–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DY, Lee JW, Lin G, Lee YK, Lee YH, Choi IS, Han SB, Jung JK, Kim YH, Kim KH, Oh KW, Hong JT, Lee MS. Obovatol attenuates LPS-induced memory impairments in mice via inhibition of NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Neurochem Int. 2012b;60:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi IS, Lee YJ, Choi DY, Lee YK, Lee YH, Kim KH, Kim YH, Jeon YH, Kim EH, Han SB, Jung JK, Yun YP, Oh KW, Hwang DY, Hong JT. 4-O-methylhonokiol attenuated memory impairment through modulation of oxidative damage of enzymes involving amyloid-beta generation and accumulation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27:127–141. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SL, Vassar R. The role of amyloid precursor protein processing by BACE1, the beta-secretase, in Alzheimer disease pathophysiology. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29621–29625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800015200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Vanderstichele H, Guhde G, Annaert W, Von Figura K, Van Leuven F. Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1998;391:387–390. doi: 10.1038/34910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui H, Diaz F, Garcia S, Moraes CT. Cytochrome c oxidase deficiency in neurons decreases both oxidative stress and amyloid formation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14163–14168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705738104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertsch J, Anavi-Goffer S. Methylhonokiol attenuates neuroinflammation: a role for cannabinoid receptors? J Neuroinflamm. 2012;9:135. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmotto M, Giliberto L, Tamagno E, Tabaton M. Oxidative stress mediates the pathogenic effect of different Alzheimer’s disease risk factors. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:3. doi: 10.3389/neuro.24.003.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herreman A, Serneels L, Annaert W, Collen D, Schoonjans L, De Strooper B. Total inactivation of gamma-secretase activity in presenilin-deficient embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:461–462. doi: 10.1038/35017105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho KY, Tsai CC, Chen CP, Huang JS, Lin CC. Antimicrobial activity of honokiol and magnolol isolated from Magnolia officinalis. Phytother Res. 2001;15:139–141. doi: 10.1002/ptr.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsinger RM, McLean CA, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Evin G. Increased expression of the amyloid precursor beta-secretase in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:783–786. doi: 10.1002/ana.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly WT, Xia W, Rahmati T, Wolfe MS, Selkoe DJ. The transmembrane aspartates in presenilin 1 and 2 are obligatory for gamma-secretase activity and amyloid beta-protein generation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3173–3178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Choi DY, Choi IS, Kim KH, Kim YH, Kim HM, Lee K, Cho WG, Jung JK, Han SB, Han JY, Nam SY, Yun YW, Jeong JH, Oh KW, Hong JT. Inhibitory effect of 4-O-methylhonokiol on lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation, amyloidogenesis and memory impairment via inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB in vitro and in vivo models. J. Neuroinflammation. 2012a;9:35. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Choi DY, Lee YK, Lee YM, Han SB, Kim YH, Kim KH, Nam SY, Lee BJ, Kang JK, Yun YW, Oh KW, Hong JT. 4-O-methylhonokiol prevents memory impairment in the Tg2576 transgenic mice model of Alzheimer’s disease via regulation of beta-secretase activity. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012b;29:677–690. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Choi DY, Yun YP, Han SB, Kim HM, Lee K, Choi SH, Yang MP, Jeon HS, Jeong JH, Oh KW, Hong JT. Ethanol extract of Magnolia officinalis prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced memory deficiency via its antineuroinflammatory and antiamyloidogenic effects. Phytother Res. 2013;27:438–447. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Choi IS, Park MH, Lee YM, Song JK, Kim YH, Kim KH, Hwang DY, Jeong JH, Yun YP, Oh KW, Jung JK, Han SB, Hong JT. 4-O-Methylhonokiol attenuates memory impairment in presenilin 2 mutant mice through reduction of oxidative damage and inactivation of astrocytes and the ERK pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YK, Choi IS, Kim YH, Kim KH, Nam SY, Yun YW, Lee MS, Oh KW, Hong JT. Neurite outgrowth effect of 4-O-methyl honokiol by induction of neurotrophic factors through ERK activation. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:2251–2260. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-0024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui N, Takahashi K, Takeichi M, Kuroshita T, Noguchi K, Yamazaki K, Tagashira H, Tsutsui K, Okada H, Kido Y, Yasui Y, Fukuishi N, Fukuyama Y, Akagi M. Magnolol and honokiol prevent learning and memory impairment and cholinergic deficit in SAMP8 mice. Brain Res. 2009;1305:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan E, Sanders S, Iwatsubo T, Takeuchi A, Saido T, Zehr C, Yu X, Uljon S, Wang R, Mann D, Dickson D, Duff K. Amyloid phenotype characterization of transgenic mice overexpressing both mutant amyloid precursor protein and mutant presenilin 1 transgenes. Neurobiol Dis. 1999;6:231–244. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Octave JN, Essalmani R, Tasiaux B, Menager J, Czech C, Mercken L. The role of presenilin-1 in the gamma-secretase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein of Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1525–1528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL, Sisodia SS. Mutant genes in familial Alzheimer’s disease and transgenic models. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:479–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambamurti K, Kinsey R, Maloney B, Ge YW, Lahiri DK. Gene structure and organization of the human beta-secretase (BACE) promoter. FASEB J. 2004;18:1034–1036. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1378fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre M, Walter J, Gentleman SM. Interactions between APP secretases and inflammatory mediators. J. Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:25. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuehly W, Paredes JM, Kleyer J, Huefner A, Anavi-Goffer S, Raduner S, Altmann KH, Gertsch J. Mechanisms of osteoclastogenesis inhibition by a novel class of biphenyl-type cannabinoid CB(2) receptor inverse agonists. Chem Biol. 2011;18:1053–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo JJ, Lee SH, Lee YS, Kwon BM, Ma Y, Hwang BY, Hong JT, Oh KW. Anxiolytic-like effects of obovatol isolated from Magnolia obovata: involvement of GABA/benzodiazepine receptors complex. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;31:1363–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamagno E, Bardini P, Obbili A, Vitali A, Borghi R, Zaccheo D, Prozato MA, Danni O, Smith MA, Perry G, Tabaton M. Oxidative stress increases expression and activity of BACE in NT2 neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:279–288. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Zhuo JM, Chu J, Chinnici C, Pratico D. Amelioration of the Alzheimer’s disease phenotype by absence of 12/15-lipoxygenase. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:922–929. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]