Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine whether britanin, isolated from the flowers of Inula japonica (Inulae Flos), modulates the generation of allergic inflammatory mediators in activated mast cells. To understand the biological activity of britanin, the authors investigated its effects on the generation of prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), leukotriene C4 (LTC4), and degranulation in IgE/Ag-induced bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs). Britanin dose dependently inhibited degranulation and the generations of PGD2 and LTC4 in BMMCs. Biochemical analyses of IgE/Ag-mediated signaling pathways demonstrated that britanin suppressed the phosphorylation of Syk kinase and multiple downstream signaling processes, including phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1)-mediated calcium influx, the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs; extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and p38), and the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway. Taken together, the findings of this study suggest britanin suppresses degranulation and eicosanoid generation by inhibiting the Syk-dependent pathway and britanin might be useful for the treatment of allergic inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Britanin, Mast cells, Eicosanoid, Degranulation, Syk kinase, Mitogen-activated protein kinase, Allergic inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Aggregation of FcɛRI results in the phosphorylation of two tyrosine residues within its immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) by Lyn, or by another member of the Src family of tyrosine kinases that associates with the receptor. Phosphorylated ITAM then serves as a docking site for Syk, and this interaction leads to the downstream propagation of signals. Syk phosphorylates adapter proteins, such as, linker for the activation of T cells (LAT), and these phosphorylations result in the formation of a macromolecular signaling complex that allows the diversification of downstream signals required for the release of various pro-inflammatory mediators (Siraganian, 2003). These signaling pathways include phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ)-mediated Ca2+ mobilization, which is a prerequisite for mast cell degranulation and subsequent arachidonic acid (AA) release from membranes by cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2), which is activated by an increase in Ca2+ influx and phosphorylation by MAPKs (Clark et al., 1991; Dennis et al., 1997). Therefore, blockade of Syk kinase could inhibit the allergen-induced releases of multiple granule-stored and newly synthesized mediators (Masuda and Schmitz, 2008). FcɛRI crosslinking also induces the activations of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, and NF-κB signaling pathways, which ultimately contribute to the inducible expressions of multiple pro-inflammatory genes, such as, cytokines and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2.

The flowers of Inular japonica (I. japonica, Inulae Flos) have long been used in traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of digestive disorders, bronchitis, and inflammation (Liu et al., 2004). Modern pharmacological studies have also described its diverse effects in the contexts of anti-diabetes, hypolipidemia, and hepatoprotection (Song et al., 2000; Kobayashi et al., 2002; Shan et al., 2006). Our group previously reported that the ethanol extract of I. japonica exhibited anti-asthmatic (Park et al., 2011) and anti-allergic activities (Lu et al., 2012a) in an in vivo animal model. Previously, we reported that the ethanol extract of I. japonica inhibited degranulation, eicosanoid generation, and in vivo antiallergic activity. In this previous report, we isolated three major sesquiterpenes by HPLC, and described the inhibitions of degranulation and eicosanoid generation by britanin and tomentosin in SCF-induced BMMCs (Lu et al., 2012a). In addition, we previously also found that the ethanol extract of I. japonica suppressed macrophages activation by LPS and that britanin suppressed the productions of nitric oxide, PGE2 and proinflammatory cytokines in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (Choi et al., 2010; Park et al., 2013). However, the mechanisms underlying the inhibitions of degranulation and eicosanoid generation by britanin have not been well established. Accordingly, we sought to determine whether britanin modulates the generation of allergic inflammatory mediators in activated mast cells. In the present study, we demonstrated that britanin inhibits degranulation, PGD2 and LTC4 generation in IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs by suppression of the Syk pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Britanin was isolated from Inulae Flos by methanol extraction as described previously (Park et al., 2013). Britanin was dissolved in 0.1% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), which did not affect BMMCs viability or activation. Therefore, a control consisting of DMSO alone was also run in all cases.

Chemicals and reagents

Mouse anti-dinitrophenyl (DNP) IgE and DNP-human serum albumin (HSA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Primary antibodies used were used: rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for phospho-IκB, IKKα/β, ERK1/2, JNK, PLCγ1, p38, β-actin, and total form for IκB, ERK1/2, JNK, p38, and 5-LO were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against NF-κB p65, Syk, LAT, PLCγ1, phospho-cPLA2 (Ser505), IKKα/β and lamin B as well as secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP and rabbit anti-goat IgG-HRP antibodies, total Syk, total LAT, and Bay 61-3606 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) and antibodies for phosphotyrosine was purchased from Millipore (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The enzyme immnoassay (EIA) kits for PGD2 and LTC4 were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) culture and activation

BMMCs were isolated from male Balb/cJ mice (Sam Taco, INC, Seoul, Korea) and were cultured at 37°C in RPMI 1640 media (Thermo Scientific, UT, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml of penicillin (Thermo Scientific, Utah, USA), 10 mM HEPES buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 100 μM MEM non-essential amino acid solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 20% PWM-SCM (poke-weed mitogen-spleen cell conditioned medium) as a source of IL-3. After 6 weeks, >98% of the cells was found to be BMMCs as determined by a previously described procedure, as described previously (Lu et al., 2011). For BMMCs stimulation, 106 cells/ml were sensitized overnight with 500 ng/ml of anti-DNP IgE, 1 h pretreated with indicated concentration of britanin or Bay 61-3606, and then stimulated for 15 min with 100 ng/ml of DNP-HSA.

Degranulation assays

After stimulating with DNP-HSA for 15 min with or without pretreatment with britanin or Bay 61-3606 for 1 h, degranulation was determined by measuring the release of β-hexosaminidase (β-Hex), a marker of mast cell degranulation, by a spectrophotometric method, as described previously (Lu et al., 2012a).

MTT assay for cell viability

Cell viability was assessed by MTT (Sigma) assay. Briefly, BMMCs were seeded onto 96 well culture plates at 2×104 cells/200 ml/well. After incubation with various concentrations of britanin for 8 h, 20 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml) was added to each well. After 4 h incubation, 150 μl of culture medium was removed, and cells were dissolved in 0.4 N HCl/isopropyl alcohol. The optical densities (OD) at 570 nm and 630 nm were measured using a microplate reader (Sunrise, Tecan, Switzerland).

Measurement of LTC4 and PGD2 amounts

IgE sensitized BMMCs were pretreated with britanin or Bay 61-3606 for 1 h and stimulated with DNP-HSA (100 ng/ml). After 15 min of stimulation, the supernatants were isolated for further analysis by EIA. LTC4 was determined using an enzyme immunoassay kit. To assess COX-2-dependent PGD2 synthesis, BMMCs were preincubated with 1 μg/ml of aspirin for 2 h to irreversibly inactivate preexisting COX-1. After washing, BMMCs were activated with DNP-HSA (100 ng/ml) at 37°C for 7 h with britanin or Bay 61-3606. PGD2 in the supernatants were quantified using PGD2 EIA kit and cells were used for immunoblots analysis.

Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ level

Intracellular Ca2+ level was determined with FluoForteTM Calcium Assay Kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), as described previously (Hwang et al., 2013). Briefly, BMMCs were preincubated with FluoForteTM Dye-Loading Solution for 1 h at room temperature. After washing the dye from cell surface with PBS, the cells (5×104) were seeded into 96-well microplates. Then the cells were pretreated with britanin or Bay 61-3606 for 1 h before adding DNP-HSA. The fluorescence was measured using a flurometric imaging plated reader at an excitation of 485 nm and an emission of 520 nm (BMG Labtechnologies FLUOStar OPITIMA platereader, Offenburg, Germany). All the assay experiments were independently repeated at least three times.

Preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts

The nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared as described previously (Lu et al., 2011). BMMCs were sensitized to DNP-specific IgE (500 ng/ml, overnight) and pretreated with britanin or Bay 61-3606 for 1 h, and then stimulated with DNPHSA (100 ng/ml) for 30 min. Cultured BMMCs were collected by centrifugation, washed with PBS and lysed in a buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluo-ride (PMSF) and 0.1% NP40 by incubation on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation at 1,000 g for 4 min, supernatants were used as a cytosolic fraction. Nuclear pellets were washed and lysed in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 25% (v/v) glycerol, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, and the protease inhibitor cocktail. This suspension was incubated for 30 min at 4°C followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g, and the resultant supernatants were used as a nuclear fraction.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (Lu et al., 2011). Cell lysates were obtained using modified lysis buffer [0.1% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol]. Total cell lysates (1 mg protein equivalent) were incubated with anti-Syk or anti-LAT antibodies for 2 h at 4°C and immunocomplexes were precipitated with 20 μl of protein A-Sepharose. Immunocomplex precipitates were then extensively washed (3 times) with ice-cold lysis buffer. These precipitates or total cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with corresponding antibodies.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously (Lu et al., 2011). BMMCs were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF), 1M dithiothreitol (DTT), 200 mM NaF, 200 mM Na3VO4, and a protease inhibitor cocktail). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,000×g for 15 min at 4°C and resulting supernatant were used for western blotting. Protein concentration was measured using the Qubit Fluorometer machine (Invitrogen, USA). Samples were separated by 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred to nitro-cellulose transfer membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were then blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with individual antibodies; primary antibodies were diluted at 1:1000 (unless otherwise stated) and incubated at 4°C overnight. Membranes were then washed three times for 10 min each with TBS-T buffer, and immunoreactive proteins were incubated with HRP-coupled secondary antibodies diluted at 1:3000 for 1 h at room temperature, washed three times for 10 min with TBS-T buffer, and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kits (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA).

Statistic Analysis

All experiments were performed three or more times. Average values are expressed as means ± S.D. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The Student’s t-test was used to compare pairs of independent groups. Statistical significance was accepted for p values <0.05.

RESULTS

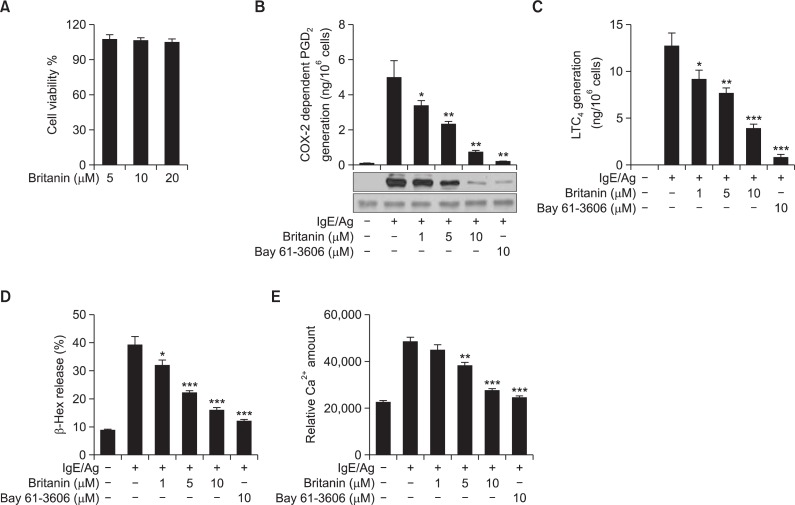

Effects of britanin on degranulation, eicosanoid generation, and intracellular calcium influx in IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs

Initially, the cytotoxicity of britanin on BMMCs was examined using the MTT assay. However, britanin did not affect cell viability up to a concentration of 20 μM (Fig. 1A). Therefore, britanin levels from 1 to 10 μM were used in subsequent experiments. Previously, we reported that PGD2 generation by BMMCs is biphasic. More specifically, after IgE/Ag stimulation, immediate (occurring within 2 h) PGD2 generation, which is regulated by constitutive COX-1, is followed by delayed (2–10 h) PGD2 generation, which is regulated by inducible COX-2 (Moon et al., 1998; Lu et al., 2011; Hwang et al., 2013). As shown in Fig. 1B, IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs showed significant augmentation of the delayed phase of PGD2 generation and amplification of COX-2 induction. In order to evaluate delayed COX-2-dependent PGD2 generation, BMMCs were pre-treated with aspirin to abolish preexisting COX-1 activity, briefly washed, and then stimulated with DNP-HSA in the presence or absence of britanin or Bay 61-3606 (a Syk inhibitor) for 7 h. The generation of PGD2 was found to be dose-dependently suppressed by britanin and COX-2 expression was concomitantly reduced. Next, we examined the effect of britanin on 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) dependent LTC4 generation, and we found that LTC4 generation was also inhibited by britanin and by Bay 61-3606 (Fig. 1C). We also examined the effect of britanin on the exocytotic secretion of β-Hex, a degranulation marker enzyme in BMMC, and found β-Hex release was markedly inhibited by britanin and by Bay 61-3606 (Fig. 1D). Intracellular Ca2+ elevation is one of the earliest events and is essential for mast cell degranulation and AA release from phospholipid and for the metabolism of phospholipid (Clark et al., 1991; Fischer et al., 2005; Flamand et al., 2006). Therefore, we examined whether britanin affects Ca2+ signals in IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs. As shown in Fig. 1E, pretreatment of BMMCs with britanin or Bay 3606 significantly decreased intracellular Ca2+ levels.

Fig. 1.

Effect of britanin on the cell viability, degranulation, PGD2 and LTC4 generation, and intracellular calcium increase in IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs. (A) BMMCs were incubated in the presence of 5, 10, or 20 μM of britanin. Cell viabilities were assayed using an MTT assay. Data represent means ± S.D of three different samples. (B) IgE-sensitized BMMCs were pre-incubated with 1 μg/ml aspirin for 2 h to abolish preexisting COX-1 activity, briefly washed, and then stimulated with DNP-HSA for 7 h. PGD2 released into the supernatant was quantified by a PGD2-MOX EIA kit and the cells were used for immunoblotting of COX-2 protein. (C) IgE-sensitized BMMCs were pre-incubated with the indicated concentrations of britanin or Bay 61-3606 for 1 h and stimulated with DNP-HSA for 15 min. LTC4 released into the supernatant was quantified using an enzyme immunoassay kit. (D) IgE-sensitized BMMCs were pre-incubated with the indicated concentrations of britanin or Bay 61-3606 for 1 h and stimulated with DNP-HSA for 15 min. β-Hex release in supernatants was measured as described in Materials and Methods. (E) IgE-sensitized BMMCs were pretreated with FluoForteTM Dye-Loading Solution for 1 h at room temperature. After washing the dye from cell surfaces with HBSS, cells were seeded into 96-well microplates, pre-incubated with britanin or Bay 61-3606 for 1 h, and stimulated with DNP-HSA. Relative calcium levels were measured using a flurometric imaging plated reader. Values are shown as the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments, *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 versus the IgE/Ag-induced group.

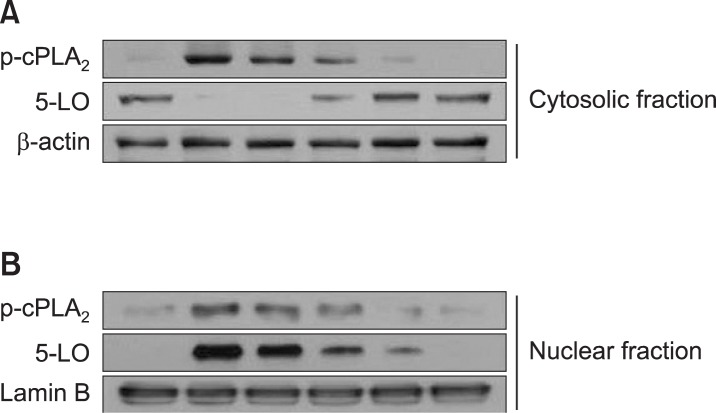

Effect of britanin on cPLA2α- and 5-LO-dependent LTC4 generation

The generation of LTC4 is regulated by two steps, namely, the liberation of AA from membrane phospholipids by cPLA2 and the oxygenation of free AA by 5-LO. Both 5-LO and cPLA2α translocate from the cytosol to the nuclear membrane in response to an increase in intracellular Ca2+ level (Fischer et al., 2005; Flamand et al., 2006), and cPLA2α is phosphorylated by MAPKs (a process necessary for the maximal release of AA) (Lin et al., 1993; Lu et al., 2011). We first examined the effect of britanin on the phosphorylations and nuclear translocations of cPLA2 and 5-LO. As was observed in our previous study (Lu et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2012b), DNP-HSA stimulation caused the translocation of some cytosolic phosphorylated cPLA2α to nuclear fractions (Fig. 2). 5-LO was localized mainly in cytosol in unstimulated BMMCs (Fig. 2A), but DNP-HSA stimulation caused the translocation of most 5-LO to the nuclear fraction (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the appearance of both cytosolic and nuclear phospho-cPLA2α and the translocation of 5-LO were inhibited by britanin and by Bay 61-3606. These results suggest that britanin and Bay 61-3606 inhibited LTC4 generation by inhibiting cPLA2α translocation, which suggests that the Syk pathway is required for LTC4 generation, as has been described previously (Lu et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2012b).

Fig. 2.

Britanin inhibits IgE/Ag-induced translocation of 5-LO and phospho-cPLA2. IgE-sensitized BMMCs were pre-incubated with britanin or Bay 61-3606 for 1 h and stimulated with DNP-HSA for 15 min. Cytosolic (A) and nuclear fractions (B) were immunoblotted with antibodies for phospho-cPLA2 (Ser505) and 5-LO. β-Actin and lamin B were used as internal controls for cytosol and nuclear fractions, respectively.

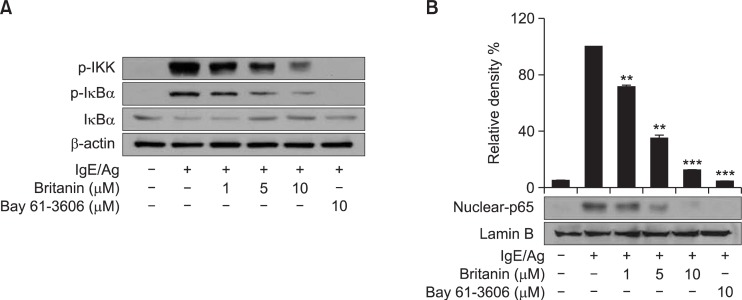

Effect of britanin on the IKK-IκBα-NF-κB pathway

Since NF-κB is an essential transcription factor for several inflammatory genes, such as, COX-2, iNOS, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Reddy et al., 2000; Tak and Firestein, 2001), we examined whether the inhibition of COX-2 by britanin suppresses NF-κB activation pathways. We and others have previously reported that the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκB by IKK leads to the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 (Reddy et al., 2000; Tak and Firestein, 2001; Lu et al., 2012b). To investigate the IgE/Ag-mediated activation of the IKK-IκBα-NF-κB pathway, BMMCs were simulated with DNP-HSA for 15 or 30 min, cytoplasmic or nuclear proteins were then examined for the phosphorylations of IKKα/β and IκBα and total protein levels. Pretreatment of BMMCs with britanin decreased the phosphorylation of IKKα/β and IκBα the degradation of IκBα (Fig. 3A), and the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 subunit (Fig. 3B). Bay 61-3606 also inhibited these signal events, indicating that the IKK-IκBα-NF-κB pathway was under the control of Syk.

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effects of britanin on IgE/Ag-induced IKK/IκBα/NF-κB pathway. (A) IgE-sensitized BMMCs were preincubated for 1 h with the indicated concentrations of britanin or Bay 61-3606 and stimulated with DNP-HSA for 15 min. Cytosol fractions were prepared for the determinations of IKKα/β and IκBα phosphorylation and total IκBα levels by immunoblotting. (B) IgE-sensitized BMMCs were pretreated with britanin or Bay 61-3606 for 1 h and stimulated by DNP-HSA for 30 min. Nuclear extracts were then analyzed by immunoblotting for the NF-κB-p65 subunit. The relative nuclear p65/lamin B protein ratios were determined by measuring immunoblot band intensities using a scanning densitometer. The results from three separate experiments as relative ratios (%) are represented. Values are shown as the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 versus the IgE/Ag-induced group.

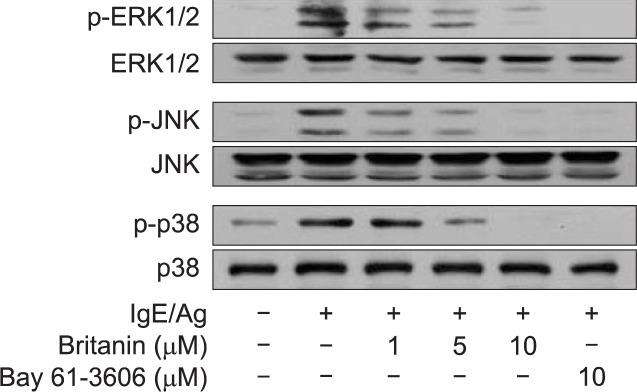

Effects of britanin on MAPKs activation in IgE-sensitized BMMCs

Previously, we reported that the inhibition of COX-2 expression and of attendant PGD2 generation occurred after NF-κB inactivation and/or treating cells with either of three MAPKs inhibitors, that is, U0126 for extracellular regulated kinase1/2 (ERK1/2), SP600125 for c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), or SB03580 for p38 MAP kinase (Lu et al., 2011). As shown in Fig. 4, when BMMCs were pretreated with britanin or Bay 61-3606 for 1 h, both compounds clearly and dose-dependently inhibited the IgE/Ag-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAP kinase. This result suggests that the inhibition of Syk by britanin may suppress MAPK activation.

Fig. 4.

Effects of britanin on MAPK pathways. IgE-sensitized BMMCs were pre-incubated for 1 h with the indicated concentrations of britanin or Bay61-3606 and then stimulated with DNP-HSA for 15 min. Cell lysates were used immunoblotted to assess the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK, and p38. The results shown represent at least three separate experiments.

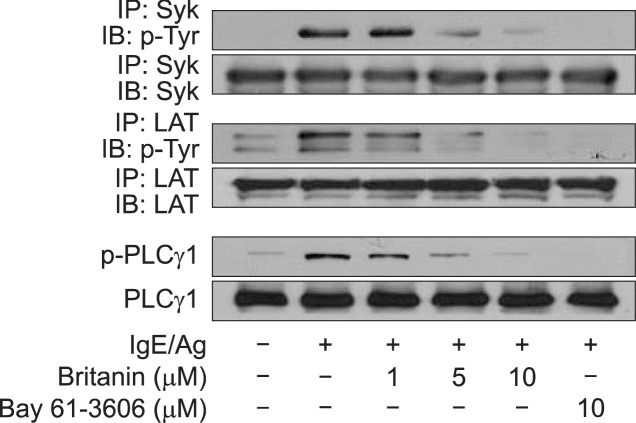

Britanin inhibited Syk activation

The tyrosine kinase Syk plays an essential role in the initiation of the FcɛRI-dependent signaling pathway, and thus, we examined whether britanin affects the phosphorylation of Syk, and the phosphorylations of LAT and PLCγ1, which lie immediately downstream of Syk (Lu et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2012b). As shown in Fig. 5, the tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk, LAT, and PLCγ1 were observed in IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs, and these phosphorylation were significantly and dose-dependently inhibited by britanin. Under the same conditions, the Syk inhibitor Bay 61-3606 (positive control) potently inhibited the phosphorylation of Syk, PLCγ1, and LAT.

Fig. 5.

Effects of britanin on phosphorylation of Syk, LAT and PLCγ1. IgE-sensitized BMMCs were stimulated with or without DNP-HSA for 5 min. Proteins were immunoprecipitated for Syk or LAT to assess their phosphorylation statuses. Phosphorylation of PLCγ1 was determined using total cell lysates. Blots are representative of three independent experiments that provided similar results.

DISCUSSION

To explore the biological activity of britanin, we investigated its effects on the generation of PGD2, LTC4, and degranulation in IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs. This study shows that britanin inhibits degranulation, PGD2 and LTC4 generation in IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs by suppressing the Syk pathway. Several sesquiterpenes, namely, britanin, tomentosin (Lu et al., 2012a), ergolide, acetylbritannilactone (Han et al., 2001; Jin et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007) and sesquiterpenes dimer inulanolides (Jin et al., 2006) have been isolated from I. japonica and evaluated for their biological activities. Ergolide, inulanolide, and britanin have been reported to inhibit the expressions of iNOS, COX-2, or TNF-α in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, whereas inulanolides inhibited LPS-induced inflammatory response in vascular smooth muscle cell (Han et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2004; Jin et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007; Park et al., 2013). Previously, we reported that I. japonica suppresses ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation and IgE/Ag-stimulated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis in a mouse model (Park et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2012a). However, we only described the effects of britanin on SCF-induced mast cell activation (Lu et al., 2012a), and thus, the mechanism responsible for the inhibitory effect of britanin on IgE/Ag-induced mast cell activation has not been reported.

When mast cells are activated by the cross-linking of IgE/Ag on their membranes, the Lyn/Syk/LAT axis phosphorylates PLCγ1 causing Ca2+ influx, which triggers degranulation and activates AA metabolizing enzymes (Cruse et al., 2005). The present study shows that britanin markedly inhibits the phosphorylations of Syk, LAT, and PLCγ1 (Fig. 5) and intracellular Ca2+ influx (Fig. 1E), and results in the inhibition of degranulation in IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs. Furthermore, britanin was found to dose-dependently inhibit the 5-LO dependent LTC4 generation that occurs within 15 min of treatment when IgE binds to FcɛRI on the membranes of BMMCs (Fig. 1C). Other groups have reported that the synthesis of LTC4 in mast cells is regulated by two steps, that is, by the activation of cPLA2α by MAPKs to facilitate the release of AA from membrane phospholipid, and by the conversion of free AA to LTC4 by 5-LO and nuclear transmembrane protein 5-LO-activating protein (FLAP), the latter of which may serve as an AA binding protein on the outer nuclear membrane (Mandal et al., 2004). The results of the present study demonstrate that the inhibition of 5-LO dependent LTC4 generation by britanin is due to the inhibition of cPLA2α phosphorylation by MAPKs and to the inhibition of the translocations of phospho-cPLA2α and 5-LO to the nuclear membrane (Fig. 2).

The other AA metabolite PGD2 (the major prostaglandin) is produced by the COX pathway in mast cells (Fischer et al., 2005). In the present study, after inactivating preexisting COX-1 activity using aspirin, BMMCs cells were stimulated with DNP-HSA for 7 h with or without britanin. As shown in Fig. 1B, britanin strongly suppressed PGD2 generation and concomitantly reduced COX-2 expression. We previously reported that britanin suppresses the generations of nitric oxide by LPS and of PGE2 generation by COX-2 and the productions of proinflammatory cytokines by inactivating NF-κB and MAPKs in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells (Park et al., 2013). In addition, it has been reported COX-2-dependent PGD2 generation in BMMCs is caused by the activations of the NF-κB and MAPKs pathways (Lu et al., 2011). Thus, we investigated the effect of britanin on the activations of these pathways in IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs. It is well known that IκBα phosphorylation precedes IκBα degradation via IKKα/β activation. In the present study, britanin was found to inhibit IgE/Ag-inducible IKK-IκBα phosphorylation (Fig. 3A), indicating it inhibits COX-2 dependent PGD2 generation by preventing the phosphorylation of IκBα, and thus, the degradation and subsequent nuclear translocation of p65 protein in BMMCs (Fig. 3B).

Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 4, britanin dose-dependently inhibited the phosphorylations of ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAP kinase, which suggests that it prevents the phosphorylation and translocation of cPLA2 to the nuclear membrane. Since both britanin and Bay 61-3606 inhibited calcium influx (Fig. 1E), MAPKs phosphorylation (Fig. 3), and the activation of the NF-κB pathway located downstream of the FcɛRI proximal Syk pathway, these results suggest that Syk plays an important roles in the generation of eicosanoids (PGD2 and LTC4) and degranulation in IgE/Ag-induced BMMCs. Because, Syk plays an essential role in the initiation of FcɛRI-dependent signaling (Siraganian, 2003; Masuda and Schmitz, 2008), we examined whether britanin suppresses Syk phosphorylation and the expressions of its downstream signal molecules. As shown in Fig. 5, the phosphorylations of Syk, LAT, and PLCγ1 were found to be significantly inhibited by britanin and by Bay 61-3606 (a Src family kinase inhibitor and positive control).

In conclusion, the present study reveals that britanin inhibits IgE/Ag-induced degranulation and the generation of LTC4 and PGD2 in BMMCs. Furthermore, biochemical analyses showed that britanin inhibited IgE/Ag-induced degranulation via the PLCγ1-Ca2+ pathway, PGD2 production via the IKK/IκBα/NF-κB/COX-2 and MAPKs pathways, and LTC4 generation through the MAPKs/cPLA2/5-LO pathway. Furthermore, the observed almost identical effects of Bay 61-3606 suggest the inhibitory effects of britanin are controlled by the Syk pathway. In a previous report, it was suggested Syk plays a central role in the activations mediated by Fc receptors (mast cells, macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils) and B cell receptors (Ruzza et al., 2009). In addition, it has been reported that Syk inhibition blocks the release of mediators like histamine, the production of PGD2 and LTC4, and the secretions of proinflammatory cytokines from activated mast cells (Lu et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2012b). For these reasons, Syk inhibitors are being increasingly considered promising therapeutic agents for the management of inflammatory diseases (Wong et al., 2004; Bajpai et al., 2008). Taken together with our previous in vitro and in vivo results (Choi et al., 2010; Park et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2012a; Park et al., 2013), britanin appears to be an good candidate for the development of novel allergic-inflammatory drugs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the 2014 Yeungnam University Research Grant.

REFERENCES

- Bajpai M, Chopra P, Dastidar SG, Ray A. Spleen tyrosine kinase: a novel target for therapeutic intervention of rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2008;17:641–659. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Park YN, Li Y, Jin MH, Lee J, Lee Y, Son JK, Chang HW, Lee E. Flowers of Inula japonica attenuate inflammatory responses. Immune Netw. 2010;10:145–152. doi: 10.4110/in.2010.10.5.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JD, Lin LL, Kriz RW, Ramesha CS, Sultzman LA, Lin AY, Milona N, Knopf JL. A novel arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic PLA2 contains a Ca2+-dependent translocation domain with homology to PKC and GAP. Cell. 1991;65:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90556-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruse G, Kaur D, Yang W, Duffy SM, Brightling CE, Bradding P. Activation of human lung mast cells by monomeric immunoglobulin E. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:858–863. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00091704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis EA. The growing phospholipase A2 superfamily of signal transduction enzymes. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:1–2. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)20031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer L, Poeckel D, Buerkert E, Steinhilber D, Werz O. Inhibitors of actin polymerisation stimulate arachidonic acid release and 5-lipoxygenase activation by upregulation of Ca2+ mobilisation in polymorphonuclear leukocytes involving Src family kinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1736:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamand N, Lefebvre J, Surette ME, Picard S, Borgeat P. Arachidonic acid regulates the translocation of 5-lipoxygenase to the nuclear membranes in human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:129–136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506513200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JW, Lee BG, Kim KY, Yoon JW, Jin HK, Hong S, Lee HY, Lee KR, Lee HW. Ergolide, sesquiterpene lactone from Inula britannica, inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclo-oxygenase-2 expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages through the inactivation of NF-kappaB. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:503–512. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SL, Li X, Lu Y, Jin Y, Jeong YT, Kim YD, Lee IK, Taketomi Y, Sato H, Cho YS, Murakami M, Chang HW. AMP-activated protein kinase negatively regulates FcɛRI-mediated mast cell signaling and anaphylaxis in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin HZ, Lee D, Lee JH, Lee K, Hong YS, Choung DH, Kim YH, Lee JJ. New sesquiterpene dimers from Inula britannica inhibit NF-kappaB activation and NO and TNF-alpha production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. Planta Med. 2006;72:40–45. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-873189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Song QH, Hong T, Kitamura H, Cyong JC. Preventative effects of the flowers of Inula britannica on autoimmune diabetes in C57BL/KsJ mice induced by multiple low doses of streptozotocin. Phytother Res. 2002;16:377–382. doi: 10.1002/ptr.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LL, Wartmann M, Lin AY, Knopf JL, Seth A, Davis RJ. cPLA2 is phosphorylated and activated by MAP kinase. Cell. 1993;72:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90666-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Liu H, Yan W, Zhang L, Bai N, Ho CT. Studies on 1-O-acetylbritannilactone and its derivative, (2-O-butyloxime-3-phenyl)-propionyl-1-O-acetylbritannilactone ester. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:1101–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YP, Wen JK, Zheng B, Zhang DQ, Han M. Acetylbritannilactone suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced vascular smooth muscle cell inflammatory response. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;577:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Li Y, Jin M, Yang JH, Li X, Chao GH, Park HH, Park YN, Son JK, Lee E, Chang HW. Inula japonica extract inhibits mast cell-mediated allergic reaction and mast cell activation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012a;143:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Li Y, Seo CS, Murakami M, Son JK, Chang HW. Saucerneol D inhibits eicosanoid generation and degranulation through suppression of Syk kinase in mast cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012b;50:4382–4388. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Yang JH, Li X, Hwangbo K, Hwang SL, Taketomi Y, Murakami M, Chang YC, Kim CH, Son JK, Chang HW. Emodin, a naturally occurring anthraquinone derivative, suppresses IgE-mediated anaphylactic reaction and mast cell activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:1700–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal AK, Skoch J, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT, Christmas P, Miller D, Yamin TT, Xu S, Wisniewski D, Evans HF, Soberman RJ. The membrane organization of leukotriene synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6587–6592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308523101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda ES, Schmitz J. Syk inhibitors as treatment for allergic rhinitis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon TC, Murakami M, Ashraf MD, Kudo I, Chang HW. Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 and endogenous cytokine expression by bacterial lipopolysaccharide that acts in synergy with c-kit ligand and Fc epsilon receptor I crosslinking in cultured mast cells. Cell Immunol. 1998;185:146–152. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HH, Kim MJ, Li Y, Park YN, Lee J, Lee YJ, Kim SG, Park HJ, Son JK, Chang HW, Lee E. Britanin suppresses LPS-induced nitric oxide, PGE2 and cytokine production via NF-κB and MAPK inactivation in RAW 264.7 cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;15:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YN, Lee YJ, Choi JH, Jin M, Yang JH, Li Y, Lee J, Li X, Kim KJ, Son JK, Chang HW, Kim JY, Lee E. Alleviation of OVA-induced airway inflammation by flowers of Inula japonica in a murine model of asthma. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2011;75:871–876. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy ST, Wadleigh DJ, Herschman HR. Transcriptional regulation of the cyclooxygenase-2 gene in activated mast cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3107–3113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzza P, Biondi B, Calderan A. Therapeutic prospect of Syk inhibitors. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2009;19:1361–1376. doi: 10.1517/13543770903207039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan JJ, Yang M, Ren JW. Anti-diabetic and hypolipidemic effects of aqueous-extract from the flower of Inula japonica in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:455–459. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siraganian RP. Mast cell signal transduction from the high-affinity IgE receptor. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song QH, Kobayashi T, Iijima K, Hong T, Cyong JC. Hepatoprotective effects of Inula britannica on hepatic injury in mice. Phytother Res. 2000;14:180–186. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(200005)14:3<180::aid-ptr589>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tak PP, Firestein GS. NF-kappaB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:7–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI11830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong BR, Grossbard EB, Payan DG, Masuda ES. Targeting Syk as a treatment for allergic and autoimmune disorders. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2004;13:743–762. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.7.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]