Abstract

Conversion of somatic cells to pluripotency by defined factors is a long and complex process that yields embryonic stem cell-like cells that vary in their developmental potential. To improve the quality of resulting induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which is important for potential therapeutic applications, and to address fundamental questions about control of cell identity, molecular mechanisms of the reprogramming process must be understood. Here we discuss recent discoveries regarding the role of reprogramming factors in remodeling the genome, including new insights into the function of c-Myc, and describe the different phases, markers and emerging models of reprogramming.

Introduction

Resetting the epigenome of a somatic cell to a pluripotent state has been achieved by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), cell fusion, and ectopic expression of defined factors such as Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc (OSKM)1–3. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotency is critical for the creation of high-quality pluripotent cells and may be useful for therapeutic applications. Moreover, gaining insight from in vitro reprogramming approaches may yield relevant information for SCNT or cell fusion-mediated reprogramming and may broaden our understanding of fundamental questions regarding cell plasticity, cell identity and cell fate decisions4–6.

Reprogramming by SCNT is rapid, is thought to be deterministic and yields embryonic stem cells (ESCs) from the cloned embryo that are similar to ESCs derived from the fertilized embryo7,8. However, the investigation of SCNT and cell fusion is difficult because oocytes and ESCs contain multiple gene products that may be involved in reprogramming. In contrast, in the transcription factor-mediated reprogramming method, the factors that initiate the process are known and can be easily modulated which makes examination of the process less complicated and easier to follow. However, the process is long, inefficient and generates induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that vary widely in their developmental potential1,2,9,10.

In this review, we focus on recent studies and technologies aimed at understanding the molecular mechanisms of cellular reprogramming mediated by transcription factors. For example, insights have been gained from methods to study single cells as well as studies of populations of cells undergoing reprogramming. We describe current views of the phases of transcriptional and epigenetic changes that occur and discuss new concepts regarding the role of OSKM in driving the conversion to pluripotency. We then consider markers of cells progressing through reprogramming and emerging models of the process. Finally, we summarize criteria that allow assessment of iPSC quality.

Phases of reprogramming

Insights gained from population-based studies

After the first demonstration of reprogramming to pluripotency by defined factors11,12, many groups raced to study the reprogramming process by analyzing transcriptional and epigenetic changes in cell populations at different time points after factor induction. These are the most straightforward experiments to perform for unraveling the molecular mechanism of this complicated process. Most studies analyzing cellular changes during the reprogramming process were performed using populations of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs).

Microarray data at defined time points during the reprogramming process13 showed that the immediate response to OSKM is characterized by de-differentiation of MEFs and upregulation of proliferation genes, consistent with the expression of c-Myc. Gene expression profiling and RNAi screening in fibroblasts revealed three phases of reprogramming termed initiation, maturation, and stabilization; the initiation phase marked by a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET)14,15. Also, BMP signaling has been shown to synergize with OSKM to stimulate a microRNA expression signature associated with MET-promoting progression through the initiation phase15.

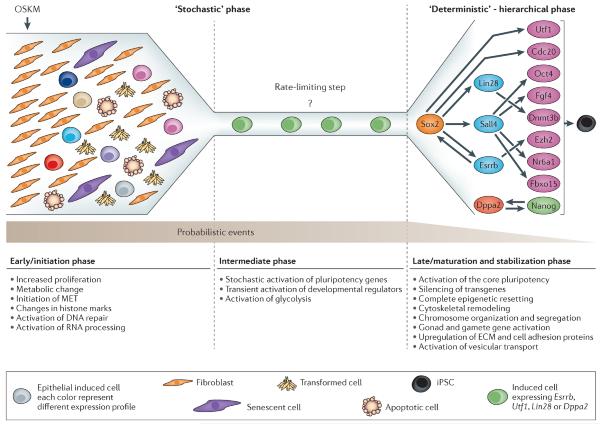

The late maturation and stabilization phases have been studied by tracing clonally-derived cells16. This study showed that repression of the OSKM transgenes is required for the transition from maturation to the stabilization phase. By comparing the expression profiles of clones that could transit from the maturation to stabilization phase to those that could not, the authors found a unique signature associated with competency. Surprisingly, few pluripotency regulators played a role in the maturation-to-stabilization transition. Rather, genes that are associated with gonads, gametes, cytoskeletal dynamics and signaling pathway were upregulated during this phase16 (Figure 1). The authors also found that genes that are induced upon transgene inhibition (for example, Eras and Lefty2) tend to be important for ESC maintenance, whereas genes that retain a similar expression level before and after transgene silencing (for example, Arid3b and Sall1) tend to be involved in regulating the maturation-stabilization transition. This study suggests that the transition to the stabilization phase upon transgene removal is dependent on regulatory pathways distinct from those controlling ESC pluripotency16.

Figure 1. Phases of the reprogramming process.

In the model we discuss in this review, the reprogramming process can broadly be divided into two phases: firstly, a long `stochastic' phase of gene activation; and secondly, a shorter hierarchical more `deterministic' phase of gene activation that begins with the activation of the Sox2 locus. After a fibroblast is induced with OSKM, it will initiate stochastic gene expression and assume one of several possible fates (such as, apoptosis, senescence, transformation, transdifferentiation or reprogramming). In the early phase, reprogrammable cells will increase proliferation, undergo changes in histone modifications at somatic genes, initiate mesenchymal to epithelial transition, and activate DNA repair and RNA processing. Then the reprogrammable cells will enter an intermediate phase with an unknown rate-limiting step that delays the conversion to iPSCs and contributes to the long latency of the process. In this phase, cells undergo a stochastic activation of pluripotency markers23, a transient activation of developmental regulators17, and activation of glycolysis18. In general the transcriptional changes in this phase are small. In some rare cases, the stochastic gene expression will lead to the activation of "predictive markers" such as Utf1, Esrrb, Dppa2, and Lin28, which then will instigate the second phase that starts with the activation of Sox2. Activation of Sox2 by the “predictive markers” can be direct or indirect and will trigger a series of deterministic events that will lead to an iPSC. In this late phase, the cells eventually stabilize into the pluripotent state in which the transgenes are silenced, the cytoskeleton is remodeled to an ESC-like state, the epigenome is reset and the core pluripotency circuitry is activated16–18,23. In this model, probabilistic events decrease and hierarchical events increase as the cell progresses from a fibroblast to an iPSC.

Another study used genome-wide analyses to examine intermediate cell populations poised to become iPSCs17. This study revealed two distinct waves of major gene activity: the first wave occurred between days 0 and 3; and the second wave started after day 9, which is toward the end of the process (day 12). The number of differentially expressed genes between progressing cells and cells that are refractory to reprogramming at each time point was gradually increased, reaching 1,500 genes by the end of the process17. The first wave was characterized by the activation of genes responsible for proliferation, metabolism, cytoskeleton organization, and downregulation of genes associated with development (Figure 1). This step occurred in the majority of cells and is equivalent to the initiation phase described above. Several early pluripotency-associated genes were upregulated gradually and some developmental and cell-type-specific genes were transiently regulated during the process. The second wave was characterized by the expression of genes responsible for embryonic development and stem cell maintenance. Genes from this step facilitate the activation of the core pluripotency network and mark the acquisition of a stable pluripotent state. In contrast, genes related to extracellular space or matrix, plasma membrane, retinoic acid binding, and immune response processes were aberrantly expressed in cells refractory to reprogramming17.

In agreement with these findings, quantitative proteomic analysis during the course of reprogramming of fibroblasts to iPSCs revealed a two-step resetting of the proteome during the first 3 days and last 3 days of reprogramming18. Proteins related to regulation of gene expression, RNA processing, chromatin organization, mitochondria, metabolism, cell cycle and DNA repair were strongly induced at an early stage and proteins related to the electron transport system were downregulated. In contrast to these processes, glycolytic enzymes exhibited slow increase in the intermediate phase, suggesting a gradual transformation of energy metabolism19. Proteins involved in vesicle-mediated transport, extracellular matrix, cell adhesion and EMT were downregulated in the early phase, retained low levels during the intermediate step and became up regulated in the final stage18. These data suggest that reprogramming is a multi-step process characterized by two waves of transcriptome and proteome resetting20.

Insights gained from single-cell studies

Knowledge gained from population-based studies is essential for the understanding of the global changes that occur in cells during the reprogramming process. A challenge for gaining mechanistic insights of reprogramming by the analysis of cell populations is cell heterogeneity. Because only a small fraction of the induced cells become reprogrammed, gene expression profiles of cell populations at different time points after factor induction will not detect changes in rare cells destined to become iPSCs. In an attempt to overcome the problem of cell heterogeneity, reprogramming has been traced at single-cell resolution using time-lapse microscopy21,22. Single-cell tracking by real time microscopy has given insights into morphological changes during reprogramming but the approach has not provided information on molecular events driving the process at the single-cell level. These studies showed that the cells underwent a shift in their proliferation rate and reduction in cell size soon after factor induction. These events occurred within the first cell division and with the same kinetics in all cells that give rise to iPSCs.

As a complementary approach to the population-based studies, two single-cell techniques have been utilized to quantify gene expression in the rare cells that undergo reprogramming23: Fluidigm BioMark, which allows quantitative analysis of 48 genes in duplicate in 96 single cells 24–27; and single-molecule-mRNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (sm-mRNA-FISH), which enables the quantification of mRNA transcripts of up to three genes in hundreds to thousands of cells28. The 48 genes in the BioMark system included those known to be involved in major events that occur during reprogramming (for example, proliferation, epigenetic modification, ESC supporting pathways, pluripotency markers and MEF markers). In the first six days after factor induction, there was high variation amongst cells in expression of the 48 genes23. This suggests that early in the reprogramming process OSKM induce stochastic gene expression changes in a subset of pluripotency genes, which are critical for instigation of the second phase (Figure 1). These stochastic changes are in addition to the alterations in expression of genes that control MET, proliferation and metabolism, which are global changes that must occur during reprogramming but are not restricted to cells that are destined to become iPSCs15–17. Single-cell analyses of clonally derived cell populations revealed that the stochastic gene expression phase is long and variable23. Although cells with an ESC-like morphology appear early, they must pass through a bottleneck - likely a rate-limiting stochastic event - before transiting into stable iPSCs23,29. At a later stage, when the cells start to express Nanog, the variation between individual cells decreases dramatically, consistent with a model in which the early stochastic phase of gene expression is followed by a deterministic or more “hierarchical” phase leading to activation of the pluripotency circuitry. This deterministic or hierarchical phase is discussed further below in the context of models of reprogramming.

Epigenetic changes

The studies discussed above characterized phases of transcriptional changes during reprogramming, so what are the epigenetic alterations that underlie these changes and what might drive them? The epigenetic signature of the somatic cell must be erased during the conversion in order to adopt a stem cell-like epigenome. These changes include chromatin reorganization, DNA demethylation of promoter regions of pluripotency genes like Nanog, Sox2 and Oct4, reactivation of the somatically silenced X chromosome, and genome-wide resetting of histone posttranslational modifications11,30–32. There are more than 100 different histone posttranslational modifications, with lysine methylation and acetylation being the ones studied most frequently33. Changes in histone marks and the role of various chromatin modifiers during reprogramming have been extensively reviewed elsewhere4,34,35, so here we briefly summarize the key points. The roles of the relevant histone marks and of chromatin modifiers are summarized in table 1 and table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Roles of various histone marks during reprogramming

| Histone mark | Function | Phase of reprogramming in which change occurs | Example of change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone H3 lysine 4 dimethylation (H3K4me2) | Marks promoters and enhancers | Early phase | Decrease at MEF and EMT genes. Increase at proliferation, metabolism, pluripotency and MET genes34,36,38,50 |

| Histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) | Marks active loci | Early phase | Increase at proliferation and metabolism genes34,36,38 |

| Histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) | Marks repressed loci | Early phase | Increase at MEF and EMT genes34,36,38 |

| Histone H3 lysine 4 monomethylation (H3K4mel) | Marks enhancers | Early phase | Increase at proliferation and metabolism genes36 |

| Histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation (H3K36me3) | Marks transcriptionally active regions | Early to Middle phase | Increase at early and late pluripotency genes36 |

| Histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation (H3K9me3) | Marks heterochromatin regions | Late phase | Decrease at late pluripotency genes50,93 |

| Histone H3 lysine 36 diimethylation (H3K36me2) | Marks potential regulatory regions (such as newly transcribed genes) | Early phase | Increase at early pluripotency genes46,47 |

| Histone H3 lysine 79 diimethylation (H3K79me2) | Marks transcriptionally active regions | Early to middle phase | Decrease at MEF and EMT genes48 |

| Histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) | Marks open chromatin and active enhancers | Unknown | Unknown |

Table 2.

Roles of example chromatin modifiers in reprogramming

| Chromatin modifier factor | Enzymatic function | Role in reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Utx | H3K27 demethylase | Physically interacts with OSK to remove the repressive mark H3K27 from early pluripotency genes41 |

| Kdm2a/2b | H3K36 demethylases | Initiation of the reprogramming process by regulating H3K36me2 levels at the promoters of early-activated genes46,47 |

| Ehmt1, Setdb1 | H3K9 methyltransferases | Required to reset the epigenome of somatic cells48 |

| Bmi1, Ring1, Ezh2, Eed, Suz12 | H3K27 methyltransferases | Involved in maintaining the transcriptional repressive state of genes48 |

| Suv39h | H3K9 methyltransferase | Contributes to heterochromatin formation, hinders the reprogramming process48 |

| Dotl1 | H3K79 methyltransferase | Inhibits the reprogramming process in the early to middle phase by maintaining the expression of EMT genes such as SNAI1, SNAI2, ZEB1, and TGFB248 |

| Parp1 | Chromatin-associated enzyme, poly(ADP-ribosyl)transferase, which modifies various nuclear proteins by poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation | Functions in the regulation of 5mC, targets Nanog and Esrrb43 |

| SWI/SNF (BAF) complex | Chromatin remodeling complex | Induce demethylation of pluripotency genes such as Oct4, Nanog and Rex145 |

| Tet1 and Tet2 | Methylcytosine dioxygenase that catalyzes the conversion of methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine | Important for the early generation of 5hmc by oxidation of 5mC, targets Nanog, Esrrb and Oct4 through physical interaction with Nanog42–44. |

| Wdr5 complex | A core member of the mammalian Trithorax (trxG) complex. An “effector” of H3K4 methylation. | Interacts with Oct4 on pluripotency gene promoters and facilitates their activation40. |

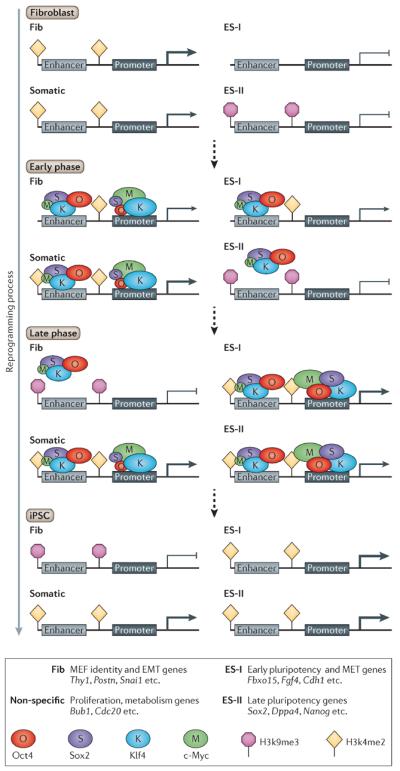

DNA demethylation and X reactivation occur late in the reprogramming process17, whereas changes in histone modifications can be seen immediately after factor induction36, suggesting that changes in histone marks are an early event that is associated with initiation of the reprogramming process. Immediately after factor induction, a peak of de novo deposition of H3K4me2 is observed at promoter and enhancer regions. At this time, H3K4me2 accumulates at the promoters of many pluripotency genes, such as Sall4 and Fgf4, which are enriched for Oct4 and Sox2 binding sites and lack H3K4me1 or H3K4me3 marks36. This stage is also associated with a gradual depletion of H3K27me3 and promoter hypomethylation in regions that are important for the conversion17. However, at early time points, H3K4me2 does not correlate with the transcription-associated histone mark H3K36me3, occupancy of RNA PolII, or transcriptional activity suggesting that these loci have not completed chromatin remodeling at early time points and an additional step is required to achieve full activation of these genes36. At the beginning of the reprogramming process, changes in these modifications are restricted almost exclusively to CpG islands, as these regions are more responsive to transcription factor activity and permissive to changes37. In parallel, the promoters of somatic genes begin to lose H3K4me2, consistent with early down-regulation of MEF markers such as Thy1 and Postn38,39. A large number of somatic gene enhancers also lose H3K4me2; this change leads to hypermethylation and silencing at later stages. Thus, epigenetic modifications of key MEF-identity factors and early pluripotency genes resulting in changes in their expression may represent one of the first steps in the conversion of somatic cells to a pluripotent state.

Chromatin modifiers involved in reprogramming

Although histone marks are robustly modified during reprogramming, it is not clear which chromatin modifiers participate in reshaping the epigenomic landscape of the somatic cells and how they are targeted to genes whose altered expression is crucial for the conversion. It is reasonable to assume that OSKM binding sites throughout the genome mark regions that will be eventually epigenetically modified. Consistent with this notion is the finding that Oct4 interacts with the WD-repeat protein-5 (Wdr5), a core member of the mammalian Trithorax (trxG) complex, on pluripotency gene promoters and this maintains global and localized H3K4me3 distribution40. The H3K27 demethylase enzyme Utx physically interacts with OSK (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4) to remove the repressive mark H3K27me3 from early activated pluripotency genes such as Fgf4, Sall4, Sall1 and Utf141. Loss of Utx is associated with aberrant H3K27me3 distribution throughout the genome and with inhibition of reprogramming41. Tet1 and Tet2, two methylcytosine hydroxylase family members that are important for the early generation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) during reprogramming, can be recruited by Nanog to enhance the expression of a subset of key reprogramming target genes such as Nanog itself, Esrrb and Oct4. Tet1 and Tet2 thus appear to be involved in the demethylation and reactivation of genes and regulatory regions that are important for pluripotency42–44. The poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (Parp1) has a complementary role in the establishment of early epigenetic marks during somatic cell reprogramming by regulating 5-methylcytosine (5mC) modification43. Brg1 and Baf155, two components of the BAF chromatin remodelling complex, enhance reprogramming by establishing a euchromatic chromatin state and enhancing binding of reprogramming factors to key reprogramming gene promoters45. Overexpression of Brg1 and Baf155 induces OSKM-mediated demethylation of pluripotency genes such as Oct4, Nanog and Rex1 and enhances conversion to iPSCs.

Many other chromatin modifiers have been shown to play a role in resetting the epigenome of reprogrammable cells (summarized in table 2). For example, Kdm2a and Kdm2b, which are H3K36me2 demethylases, cooperate with Oct4 and play a role in facilitating the reprogramming process by regulating H3K36me2 levels at the promoters of early-activated genes: mainly epithelial-associated genes, the microRNA 302/367 cluster and early pluripotency genes46,47. In the conversion of human fibroblasts to iPSCs, the H3K9 methyltransferases EHMT1 and SETDB1, and five components of the Polycomb repressive complexes (PRC) (BMI1, RING1 from PRC1, and EZH2, EED and SUZ12 from PRC2), are required to reset the epigenome of the somatic cells; loss of these genes significantly reduces iPSC formation48.

Another H3K9 methyltransferase, SUV39H, which contributes to heterochromatin formation49, hinders the reprogramming process. This suggests that loss of SUV39H may have a global effect on chromatin organization that leads to aberrant transcriptional regulation or that H3K9 methyltransferases have different specificities, with some targeting somatic state-associated genes and others targeting pluripotency-associated genes. Similarly, the histone H3 lysine 79 (H3K79me2) methyltransferase DOT1L inhibits the reprogramming process in the early to middle phase. Loss of DOT1L increases reprogramming efficiency by facilitating loss of H3K79me2 from fibroblast-associated genes such as the mesenchymal master regulators, SNAI1, SNAI2, ZEB1, and TGFB2. Silencing of these genes is essential for proper reprogramming and indirectly increases the expression of the pluripotency genes NANOG and LIN2848.

It will be interesting to explore whether specific combinations of chromatin modifiers are able to reset the epigenome of a somatic cell and to reprogram it to pluripotency in the absence of pluripotency factors. In addition, these data raise the question whether the four factors themselves act as pioneer factors that direct conversion by physical interaction with epigenetic and transcriptional regulators.

Roles of the OSKM factors

OSK as pioneer factors

Little is known about how ectopic expression of OSKM drives the conversion of somatic cells to the pluripotent state. It has been shown that the first transcriptional wave is mostly mediated by c-Myc and occurs in all cells whereas the second wave is more restricted to reprogrammable cells and involves a gradual increase in the expression of Oct4 and Sox2 targets, leading to the activation of other pluripotency genes that aid in the activation of the pluripotency network. Klf4 seems to support both phases by repressing somatic genes during the first phase and facilitating the expression of pluripotency genes in the second phase17.

In mouse or human fibroblasts, immediately after factor induction, OSKM occupy accessible chromatin, binding promoters of genes that are active or repressed34,36,38,50. In addition, OSK proteins become associated with distal elements of many genes throughout the genome that display minimal, if any, preexisting histone modifications or DNase I hypersensitivity (Figure 2)50. Thus, the multiple distal genomic sites initially occupied by OSK do not correspond to the distal genomic regions that are bound by these pluripotency factors in ESCs; we will refer to this atypical binding of ectopic OSK in somatic cells as “promiscuous binding” throughout the manuscript. Based on these observations it has been suggested that OSK may act as “pioneer” factors that open chromatin regions and allow the activation of those genes that are essential for establishment and maintenance of the pluripotent state50, whereas c-Myc only facilitates this process (the mode of action by which c-Myc aids in the conversion is discussed extensively in the next section).

Figure 2. OSKM as pioneer factors for remodeling the epigenome.

During reprogramming, exogenous OSKM bind enhancers and promoters of fibroblast and ESC genes along with regions that are not occupied by OSKM in ESCs and are not specific to fibroblasts (here called `somatic'). The factors mark the loci that eventually will be epigenetically modified. In general, OSKM bind four different classes of genes. The first class (Fib) contains genes that are important for the identity of the fibroblasts such as Thy1, Postn, Col5a2 and EMT genes like SnaiI, SnaiII and Twist1. The second class (Somatic) contains genes that are bound by OSKM in somatic cells but not in ESCs and are not specific to fibroblasts. This includes apoptotic genes such as p53, genes that are important for proliferative cells, such as cell cycle genes (for example Bub1, Cdc20 and Cdc25c), and metabolic genes such as Pfkl and Gp. The third class (ES-I) contains ESC genes that are activated early in the process such as Fbxo15, Fgf4 and Sall4. The fourth class (ES-II) contains genes that are activated late in the reprogramming process such as Sox2, Nanog and Dppa4. During the early phase of reprogramming, OSKM occupy the enhancers of all classes except enhancers of ES-II genes that contain the heterochromatin mark H3K9me3 and are refractory to the four factors. c-Myc and Klf4 bind promoters of Fib genes and repress their activity while increasing the activation of genes from the Somatic class (shown by the weight of the arrow). As a result, enhancers and promoters from Fib start to lose H3K4me2 while genes from the Somatic class maintain high levels of H3K4me2. OSK act as pioneer factors and occupy the distal enhancer of ES-I genes, which gain de novo H3K4me2 and will initiate expression a few days later. The late phase is less well understood, but it can be speculated that Fib genes become heterochromatic and are silenced while the genes from the Somatic class are highly activated. ES-I genes are highly activated and contain high levels of H3K4me2 and ES-II genes start to lose the H3K9me3 mark, gain H3K4me2 marks and initiate expression. It is reasonable to assume that more pluripotency late factors that are switched on late in reprogramming are needed to open those “blocked” regions. After the silencing of the exogenous factors, all groups are highly expressed except Fib, which remains silenced. The sizes of the ovals representing OSKM indicate their binding preference. For example, c-Myc is a global amplifier of gene expression increasing the transcription at all active promoters, therefore the oval “M” is larger on promoters.

The initial promiscuous binding of OSKM, when expressed in fibroblasts, to target sequences present in many genomic regions raises the question of their molecular role in the conversion of somatic cells to pluripotent cells. Vector transduction-mediated or doxycycline-induced expression of the reprogramming factors in fibroblasts probably does not mimic the expression mode of the endogenous genes in ESCs, in terms of expression levels and factor stoichiometry. This may result in the widespread and seemingly promiscuous binding of OSKM to multiple regions in the genome, many of which are not occupied by these factors in ESCs. Possibly, OSKM can interact with the Mediator or Cohesin complexes or with RNA pol II elongation factor Ell3 and recruit them initially to atypical distal enhancers to aid in the opening of these “closed” regions51,52. Mediator bridges interactions between transcription factors at enhancers and the transcription initiation apparatus at core promoters and in combination with RNA polymerase II and TATA-binding protein (TBP) may gradually initiate transcription from those “blocked” regions51. Binding of the “pioneer” factors OSK to “super enhancers” and the recruitment of the Mediator complex may provide cell type specificity53 at later stages in the reprogramming process. Supporting the notion that OSKM are capable of “loosening” chromatin and inducing cell plasticity early in reprogramming is the observation that transient expression of the factors is sufficient to open the chromatin and to induce transdifferentiation of fibroblasts to other somatic cells, such as cardiomyocytes and neural progenitor cells54,55.

Though the four factors often bind jointly to their targets, subsets and different combinations of the factors frequently occupy non-overlapping genomic regions. For example, Klf4 and c-Myc frequently bind jointly to promoters, whereas all the other OSKM combinations predominantly occupy distal elements, at sites conserved between human and mouse50. OSKM bind together at gene regions that initiate and support the conversion to pluripotency, such as Glis1, mir-302/367 cluster, Fbxo15, Fgf4, Sall4 and Lin28, and factors that promote mesenchymal to epithelial transition (MET)14,23,50,56–59. However, only half of the enhancers that acquire H3K4me2 in the induced cells are shared enhancers with ESCs36 with the other half representing enhancers that are not ESC-specific, supporting the promiscuous binding of OSKM to various genomic regions that aid in the conversation process (Figure 2). Also, in addition to the four factors, activation of other genes early in the reprogramming process may affect the efficiency and specificity of OSKM binding. Binding of the “pioneer” factors OSK in combination with c-Myc to enhancer regions that are not ESC-specific results in ectopic gene expression. This may render the initial cells susceptible to other gene expression changes, such as activation of apoptotic genes, metabolic genes and MET-inducing genes, silencing of MEF specific genes and eventually activation of pluripotency genes17 (Figure 2).

Revisiting the function of c-Myc in reprogramming

Because c-Myc enhances the transcription of proliferation-associated genes60–62, its role in cellular reprogramming was initially attributed to its ability to promote proliferation and to activate a set of pluripotency genes and microRNAs. C-Myc is a basic helix loop helix (bHLH) transcription factor that at basal levels interacts with Max on actively transcribed genes via E-box sequences63. It has been shown to be dispensable for reprogramming but facilitates the emergence of rare reprogrammed cells64,65. Supporting this observation is the finding that c-Myc does not greatly contribute to the activation of pluripotency regulators in partially reprogrammed cells and that its expression is essential only for the first five days38. However, in ESCs, c-Myc augments the transcription elongation of many actively transcribed genes via their core promoter regions and by these means maintains pluripotency66.

Recently, the role of c-Myc during transcription has been revisited, and it has been demonstrated that c-Myc does not regulate a unique set of target genes but rather acts as a general amplifier of gene expression, increasing the transcription at all active promoters67,68. In contrast to many other transcription factors that activate genes in a binary switch way69, c-Myc binding resembles a continuous, analog process67: c-Myc binding to promoter regions is associated with open chromatin marks including H3K4me3 and H3K27ac and is correlated with the amount of RNA polymerase recruited at those promoters67,68. C-Myc recruits the pause release factor P-TEFb, increases transcriptional elongation and the transcription levels66,70,71 and when overexpressed, its localization to the enhancers of active genes is increased substantially through binding to a variant E-box motif. When OSK are overexpressed together with c-Myc, OSK act as pioneer factors to enable c-Myc to bind to regions that are in inaccessible chromatin. In parallel, driven in part by a variant c-Myc binding site50, c-Myc also cooperatively enhances the initial OSK engagement with chromatin. Continuous binding of the factors to those “blocked” distal elements leads to binding at the promoters of genes that acquire a de novo H3K4me2, and eventually leads to the transcription of those genes.

It will be interesting to examine whether in cancer cells other pioneer factors recruit c-Myc to specific “blocked” regions through the variant E-box motif. Given this notion, c-Myc expression should enhance any given transdifferentiation or cellular reprogramming process. However, expression of c-Myc in combination with transcription factors that generate iPSCs but lack Oct4 (such as Sall4, Nanog, Esrrb and Lin28) only slightly enhanced the reprogramming process23, suggesting that different key factors have a different affinity for c-Myc. Future studies should address how different key factors cooperate with this master transcriptional amplifier.

Factor stoichiometry

The number of proviruses in iPSCs differs widely among the factors, suggesting that reprogramming requires different expression levels of the individual factors23,31. Indeed, factor stoichiometry can profoundly influence the epigenetic and biological properties of iPSCs, as was demonstrated by comparing two genetically characterized doxycycline-inducible transgenic ”reprogrammable” mouse strains72,73. The authors showed that, although a high number of iPSC colonies could be obtained, about 95% exhibited aberrant methylation of the Dlk1-Dio3 locus and were unable to generate mice derived entirely from iPSCs (“all-iPSC” mice) by tetraploid complementation, which is the most stringent test for pluripotency73. In contrast, another study using an almost identical “reprogrammable” transgenic donor mouse strain showed that the majority of iPSCs had retained normal imprinting at the Dlk1-Dio3 locus and were competent to generate “all-iPSC” mice by tetraploid complementation72. The only difference between the two transgenic systems was a different stoichiometry of the reprogramming factors: high quality iPSCs resulted from the donor strain that generated 10 to 20 fold higher levels of Oct4 and Klf4 protein and lower levels of Sox2 and c-Myc72 than the donor strain that produced low quality iPSCs73. Consistent with this notion, two other studies concluded that high levels of Oct4 and low levels of Sox2 are preferable for iPSC generation74,75.

The levels of transgene expression also play a role in the formation of partially reprogrammed iPSCs. It has been shown that partially reprogrammed colonies express a unique set of genes that are often bound by more reprogramming factors in the intermediate state than in ESCs38 (for example, promoter or enhancer regions that are bound only by Oct4 and Sox2 in ESCs are bound by OSKM in the intermediate stage). In contrast, genes that are highly expressed in ESCs are bound by fewer reprogramming factors in the partially reprogrammed cells. Promoter regions bound by OSKM in partially reprogrammed cells often contain known DNA binding sites for the bound factors, indicating that the factors might bind those sites when the factors are present at high levels. These observations are consistent with the notion that excess levels of transgenes or different factor stoichiometry can cause binding of the four factors in a manner that differs from that seen in ESCs. Therefore, the promiscuous binding of OSKM may be influenced by the stoichiometry of the four factors and can either facilitate or block reprogramming.

Other parameters known to affect the characteristics of pluripotent cells are the culture conditions and supplements used to derive the cells76. For example, addition of small molecules and supplements such as vitamin C, valproic acid (VPA) and Tgf-β inhibitors to the medium lead to more efficient derivation of iPSCs77–80. More importantly, derivation of iPSCs in the absence of serum and in the presence of vitamin C produced high quality tetraploid complementation-competent iPSCs even when a suboptimal factor stoichiometry was used for inducing pluripotency81,82. In addition, use of physiological oxygen levels during the isolation of human ESCs (hESCs) led to hESCs with two active X chromosomes, whereas X inactivation occurs if conventional conditions are used83. Thus, the available evidence suggests that factor stoichiometry as well as specific culture conditions strongly affect the quality and the efficiency of iPSC generation (summarized in Table 3).

Table 3.

Parameters that influence the quality of iPSCs

| Parameter | Reprogramming cocktail or conditions | Effect on the quality of iPSCs |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometry | High Oct4, high Klf4, low Sox2, low c-Myc | Low reprogramming efficiency, normal Dlkl-Dio3 (A) methylation, no tumors in mice, improved efficiency to produce 4n mice72 |

| High Sox2, high c-Myc, low Oct4, low Klf4 | High reprogramming efficiency, aberrant methylation of Dlkl-Dio3, tumors in mice, low efficiency to produce 4n mice73 | |

| Other factors | Tbx3 (B), Zscan4 C | Improve reprogramming efficiency and/or improved efficiency to produce 4n mice125,126 |

| Culture conditions | Knockout DMEMD, 20% KSRE | Efficient generation of iPSCs from MEFs and TTFs, improved efficiency to produce 4n mice127 |

| O2 levels | Hypoxia conditions improve iPSC generation and aid X reactivation83 | |

| Supplement | Vitamin C | Activates Dlkl-Dio3 locus, improved efficiency to produce 4n mice82 |

| Histone deacetylase inhibitor | Activates Dlkl-Dio3 locus, improved efficiency to produce 4n mice.73 | |

| 2i/LIFF | Upregulation of Oct4 and Nanog, competence for somatic and germline chimerism128 | |

| Protein arginine methyltransferase inhibitor AMI-5 and Tgf-βG inhibitor A-83-01 | Improved efficiency to produce 4n mice129 | |

| Genetic and epigenetic background | Not applicable | Unknown |

Imprinted control domain that contains the paternally expressed imprinted genes DLK1, RTL1, and DIO3 and the maternally expressed imprinted genes MEG3 (Gtl2), MEG8 (RIAN), and antisense RTL1 (asRTL1). Reported to distinguish “good” (those that generate all-iPSC mice and contribute to chimeras) iPSCs from “bad” (those that do not generate all-iPSC mice and contribute to chimeras) iPSCs in Stadtfeld et al. Nature 2010. Carey et al. Cell Stem Cell 2011 found that loss of imprinting at the Dlkl-Dio3 locus did not strictly correlate with reduced pluripotency.

Tbx3 encodes a transcriptional repressor involved in developmental processes.

Zscan4 encodes a protein involved in telomere maintenance, specifically aiding cell in escaping senescence. Also plays a role as a pluripotency factor.

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

KnockOut Serum Replacement

Leukemia Inhibitory Factor

Transforming Growth Factor Beta

4n mice: mice produced through tetraploid complementation

Markers of reprogramming

Ectopic expression of the reprogramming factors induces a heterogeneous population of cells with individual cells embarking on different fates such as cell death, cell cycle arrest (senescence), uncontrolled proliferation (malignant transformation), transdifferentiation and partial or full reprogramming (Figure 1). Although it is easy to differentiate between non-reprogrammed and reprogrammed cells, it is more challenging to distinguish partially from fully reprogrammed cells. This is because partially reprogrammed cells can be morphologically identical to ESCs and can express many pluripotency genes23. Also, due to the stochastic nature of reprogramming29, no molecular markers have been identified that would predict whether a given cell early in the process will generate an iPSC daughter. Changes including loss of MEF markers, activation of the MET program or appearance of markers such as stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 (SSEA1) or alkaline phosphatase (AP) must occur in the reprogramming process, but these are not restricted to cells destined to become iPSCs23,18,59.

To define molecularly the various phases of the reprogramming process, global gene expression and proteomic patterns of clonal cell populations or enriched populations were established at different stages after factor induction15–18. These analyses suggested genes such as Fbxo15, Fgf4, Sall1, Fut9, Chd7, Cdh1 mark the initiation phase, genes including Sall4, Oct4, Nanog, Eras, Nodal, Sox2 and Esrrb are activated during the intermediate or maturation phase, and genes such as Zfp42, Gdf3, Dppa2, Dppa3 and Utf1 might define the late or stabilization phase. However, the information from gene expression or proteomic analyses of heterogeneous populations is limited because the rare cells destined to become iPSCs are masked.

Single-cell expression analyses of intermediate SSEA1-positive cells identified early, intermediate and late makers, These included the early epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM), the intermediate c-Kit receptor and the late platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM1)17. Sorting SSEA1-positive, EpCAM-positive early cells showed modest increase in reprogramming efficiency, but could not predict which cells would eventually reprogram17. Pluripotency genes such as Utf1, Esrrb, Lin28 and Dppa2 were identified as potential “predictive” indicators that were activated in a small subset of cells and might mark cells early in the process that are destined to become iPSCs23. Some of these markers were also detected in the population-based studies but, in contrast to single cell analyses, were only detected at late stages of the process and thus could not identify potential genes whose activation may constitute early markers for cells destined to become iPSCs. The question whether these genes execute a crucial role in the conversion to fully reprogrammed cells or only mark those rare cells is unresolved.

Endogenous copies of the key reprogramming factors Oct4 and Sall4 are activated early in rare cells but are also activated in partially reprogrammed cells and thus do not represent “predictive” early markers for iPSC generation23; this was confirmed in a study using an inducible Oct4 lineage label84. In agreement with these observations, Sall4 and endogenous Oct4 have been found to be poor predictors of reprogramming competency16.

Models of reprogramming

Somatic stem cells vs. differentiated donor cells

Because the generation of cloned animals by SCNT is so inefficient, it was hypothesized that cloned animals like Dolly the sheep may not have been derived from differentiated cells as assumed but rather from rare somatic stem cells present in the heterogeneous donor cell population85. This issue was resolved when mature B and T cells were used as donors to create monoclonal mice that carried in all tissues the immunoglobulin and T cell receptor rearrangements of the B and T cell donors, respectively, thus proving a terminally differentiated donor cell86. Similarly, because reprogramming by transcription factors is inefficient, it appeared possible that only a fraction of cells are able to generate iPSCs, consistent with an “elite model” in which only rare somatic stem cells present in the donor population could generate iPSCs whereas the differentiated cells would be refractory to reprogramming87,88. Several lines of evidence rule out the elite model and argue that all cells, including terminally differentiated cells, have the potential to generate iPSC daughters. Firstly, iPSC colonies have been derived from terminally differentiated cells such as B cells, T cells, liver and spleen cells82,89–91. As with SCNT, specific genomic rearrangement of the immunoglobulin locus or the T cell receptor in iPSC clones proved unambiguously that the cells were indeed derived from mature B or T cells and excluded the possibility of mesenchymal stem cell contamination90. Secondly, clonal analysis of single B cells indicated that >90% have the potential to generate daughter cells that at some point become iPSCs29.

The stochastic and deterministic modes of reprogramming

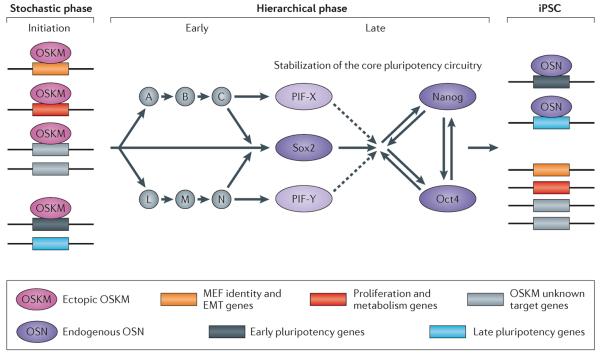

In principle, reprogramming of somatic cells could occur by two mechanisms: a “stochastic” mode in which iPSCs appear with variable latencies; or a “deterministic” mode in which reprogrammed cells would be generated with a fixed latency. In the stochastic model it cannot be predicted whether or when a given cell would generate an iPSC daughter. Strong support for the stochastic model comes from single-cell cloning experiments demonstrating that sister cells from an early colony generate iPSCs with variable latency and with some sister cells never giving rise to iPSCs23,92. Though it cannot be predicted whether or when a given cell will generate an iPS daughter cell, activation of some genes such as Esrrb or Utf1 (as discussed above), may mark rare early cells that are on their path to iPSCs (Figure 3). Activation of these genes early in the process suggests that their promoter regions are accessible for OSKM (Figure 2)15–17,23. In contrast, late activated loci are marked by H3K9me3 and are refractory to OSKM binding at early stages and activation of these loci appears to be a critical step for the proposed transition from a stochastic to a deterministic phase (Figure 1 and 3;50,93). Indeed, several essential pluripotency loci that are marked by H3K9me3, such as Nanog, Dppa4, Gdf3 and Sox2, are activated later in reprogramming and are refractory to activation by the reprogramming factors during early stages13,15,16,23,38,50 (Figure 1 and 2). Thus, the removal of H3K9me3 may represent another primary epigenetic barrier to complete reprogramming93.

Figure 3. Model of molecular events that precede iPS formation.

In the early phase, ectopic OSKM act as pioneer factors and occupy many genomic regions and help to generate a hyperdynamic chromatin state. OSKM will bind many regions throughout the genome of the fibroblast that are not OSKM targets in ESCs. Among these regions are: genes that determine the identity of the fibroblast, like extracellular components and EMT genes (orange box); genes that promote proliferation and increase metabolism (red box); unknown target genes that facilitate genomic fluidity, i.e., a state that allows rapid changes in transcription (gray box). In addition, OSKM will occupy distal regions of early pluripotency genes (black box); this binding will aid in activating those loci at later stages. A group of late pluripotency genes (blue box) is refractory to OSKM binding in this early phase. In the early hierarchical phase (which is more speculative), early pluripotency genes become activated in rare individual cells and either directly or in a hierarchical manner will instigate a more deterministic process that eventually leads to the activation of Sox2. Sox2 represents one gene of a group of late pluripotency initiating factors (PIFs) that are essential for the activation of the core pluripotency circuitry. Once activated, the endogenous pluripotency proteins Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog (OSN) occupy their target genes94 and maintain the iPSC state in the absence of the exogenous factors.

The key event initiating the late hierarchical phase appears to involve activation of the endogenous Sox2 gene, which then triggers a series of steps of gene activation that allow the cells to enter the pluripotent state23 (Figure 1 and 3). Sox2 represents one of a group of pluripotency initiating factors (PIFs) that are crucial and indispensable for the instigation of the deterministic phase16,23. The hierarchical network displayed in Figure 1 predicts that factors other than the canonical Yamanaka factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc or Nanog should be able to induce pluripotency. Indeed, down-stream factors such as Esrrb, Lin28, Dppa2 and Sall4 were sufficient to induce iPSCs from MEFs23.

It has been suggested that the initial response to ectopic expression of OSKM in somatic cells may be an orchestrated and possibly deterministic response involving epigenetically definable events that activate loci critical for pluripotency17,22. Here we suggest an alternative view of the initial interaction of OSKM with the genome. As outlined in Figure 3, initial stochastic gene activation may render the cells susceptible to other gene expression changes (such as activation of apoptotic genes, metabolic genes, MET-inducing genes, silencing of MEF specific genes and eventually activation of pluripotency genes)17. During this initial phase, stochastic OSKM-genome interactions could also instigate the activation of early PIFs such as Esrrb or Utf123 in rare cells (Figure 3), and these would eventually lead to the expression of the late pluripotency genes Sox2 and Nanog and stabilization of the core pluripotency circuitry. At this later stage, the endogenous pluripotency factors (Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog (OSN)) will, in contrast to the exogenous OSKM factors, occupy only ESC-specific target regions94.

The initial promiscuous interaction of OSKM with the genome might be initiated by any factor that destabilizes the compacted chromatin typical of somatic cells. It is this destabilization that may render the somatic chromatin susceptible to becoming “hyperdynamic”, which is the hallmark of the ESC epigenetic state95,96. Consistent with this notion are the findings that general chromatin remodeling complexes such as BAF45,97, or global basal transcription machinery components like the transcription factor IID (TFIID) complex98, or exposure of cells to general DNA methyltransferase and histone deacetylase inhibitors like 5-azacytidine13 and valporic acid78, can substantially enhance reprogramming in cooperation with OSKM. Also, in fibroblasts, down-regulation of the global chromatin organization modulator Lamin A, which is not expressed in ESCs99, has been reported to increase reprogramming efficiency100. Thus, although OSKM are highly efficient in inducing pluripotency, any chromatin remodeler or transcription factor - even those that do not normally function in ESCs - might be able to initiate the process leading to pluripotency, albeit with an efficiency that might be too low to be detected in standard reprogramming assays.

It has been suggested that reprogramming by SCNT or by somatic cell-ESC fusion is deterministic as it leads to activation of the somatic Oct4 within two cell divisions (in the case of SCNT) or in the absence of DNA replication (in the case of fusion)1,2. However, to define pluripotency functionally in cloned embryos or in heterokaryons has been difficult, so it remains to be determined whether these methods activate the pluripotency circuitry by deterministic or stochastic mechanisms. Both types of mechanism might be involved in the various forms of reprogramming.

How similar are ES and iPS cells?

Although ESCs and iPSCs are similar in morphology, age-affected cellular systems such as telomeres and mitochondria101,102, surface markers and overall gene expression, a number of studies have identified biological and epigenetic differences between ESCs and iPSCs as well as among individual ESC and iPSC lines103–115. For example, genetic alterations and differences in the transcriptome, proteome and epigenome were detected when ESCs and iPSCs were compared; these have raised concerns about the safety of iPSCs for therapeutic applications. However, other studies have failed to find epigenetic and genetic abnormalities that consistently distinguish iPSCs from ESCs105,116–119. Rather, these data suggested that the extent of variations seen between ESCs and iPSCs were similar to variations seen within different ESC lines or within different iPSC lines120.

Recently, it has been suggested that the genetic abnormalities seen in iPSCs might be a result of oncogenic stress induced by the four reprogramming factors121. Significantly higher level of phosphorylated histone H2AX, one of the earliest cellular responses to double-strand breaks (DSBs) DNA, was detected in cells exposed to OSKM or OSK. The authors also linked the homologous recombination pathway, a pathway essential for error-free repair of DNA DSBs, to the reprogramming process and suggested a direct role for this pathway in maintaining genomic integrity121. In summary, the available evidence has not settled whether the alterations seen in iPSCs are the result of the reprogramming process per se or due to pre-existing genetic and epigenetic differences within individual parental fibroblasts119,122.

Much evidence indicates that the biological properties, such as in vitro differentiation, differ among individual ESC and iPSC lines, raising the concern that the unpredictable variation among cell lines could pose a potentially serious problem for iPS-based disease research. That is, a subtle phenotype seen between a disease-specific iPSC and a control iPSC line might not be relevant to the disease but rather reflect a system immanent difference123. Efforts have been directed towards defining experimental conditions of iPSC and ESC derivation that affect the developmental potential of the cells (summarized in Table 3).

Perspective

The 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine was awarded to Shinya Yamanaka and John Gurdon for their discoveries on reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotency124. The seven years since Yamanaka's first demonstration of somatic reprogramming using defined factors12 have witnessed much progress in understanding this complex process, and the most straightforward experiments have been done. However, many questions pertaining to the molecular mechanism of reprogramming remain unsolved. For example: how do OSKM convert chromain to a “hyperdynamic” state; how does the promiscuous binding of OSKM in somatic cells contributed to the reprogramming process; what defines the rate-limiting step; what are the criteria for and the most effective methods for producing high quality iPSCs? Addressing these questions will be essential for a deeper understanding of reprogramming and will require the development of new technologies allowing genome wide epigenetic analyses of individual cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Meelad Dawlaty, Abenour Soufi and Ken Zaret for insightful comments on the manuscript. Y.B. is supported by an NIH Kirschstein NRSA (1 F32 GM099153-01A1). D.A.F. is a Vertex Scholar and was supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship and Jerome and Florence Brill Graduate Student Fellowship. R.J. is an adviser to Stemgent and a cofounder of Fate Therapeutics and is supported by US NIH grants R37-CA084198 and RO1-CA087869.

References

- 1.Jaenisch R, Young R. Stem cells, the molecular circuitry of pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming. Cell. 2008;132:567–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamanaka S, Blau HM. Nuclear reprogramming to a pluripotent state by three approaches. Nature. 2010;465:704–12. doi: 10.1038/nature09229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasque V, Miyamoto K, Gurdon JB. Efficiencies and mechanisms of nuclear reprogramming. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2010;75:189–200. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2010.75.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vierbuchen T, Wernig M. Molecular roadblocks for cellular reprogramming. Mol Cell. 2012;47:827–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buganim Y, Jaenisch R. Transdifferentiation by defined factors as a powerful research tool to address basic biological questions. Cell Cycle. 2012;11 doi: 10.4161/cc.22665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stadtfeld M, Hochedlinger K. Induced pluripotency: history, mechanisms, and applications. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2239–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.1963910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakayama S, et al. Equivalency of nuclear transfer-derived embryonic stem cells to those derived from fertilized mouse blastocysts. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2023–33. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brambrink T, Hochedlinger K, Bell G, Jaenisch R. ES cells derived from cloned and fertilized blastocysts are transcriptionally and functionally indistinguishable. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:933–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510485103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao XY, et al. iPS cells produce viable mice through tetraploid complementation. Nature. 2009;461:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature08267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang L, Wang J, Zhang Y, Kou Z, Gao S. iPS cells can support full-term development of tetraploid blastocyst-complemented embryos. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:135–8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikkelsen TS, et al. Dissecting direct reprogramming through integrative genomic analysis. Nature. 2008;454:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nature07056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li R, et al. A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samavarchi-Tehrani P, et al. Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golipour A, et al. A late transition in somatic cell reprogramming requires regulators distinct from the pluripotency network. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:769–82. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polo JM, et al. A Molecular Roadmap of Reprogramming Somatic Cells into iPS Cells. Cell. 2012;151:1617–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansson J, et al. Highly Coordinated Proteome Dynamics during Reprogramming of Somatic Cells to Pluripotency. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1579–92. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Nuebel E, Daley GQ, Koehler CM, Teitell MA. Metabolic Regulation in Pluripotent Stem Cells during Reprogramming and Self-Renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:589–95. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sancho-Martinez I, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Stem cells: Surf the waves of reprogramming. Nature. 2013;493:310–1. doi: 10.1038/493310b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araki R, et al. Conversion of ancestral fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:213–20. doi: 10.1002/stem.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith ZD, Nachman I, Regev A, Meissner A. Dynamic single-cell imaging of direct reprogramming reveals an early specifying event. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:521–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buganim Y, et al. Single-cell expression analyses during cellular reprogramming reveal an early stochastic and a late hierarchic phase. Cell. 2012;150:1209–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo G, et al. Resolution of cell fate decisions revealed by single-cell gene expression analysis from zygote to blastocyst. Dev Cell. 2010;18:675–85. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diehn M, et al. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:780–3. doi: 10.1038/nature07733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Citri A, Pang ZP, Sudhof TC, Wernig M, Malenka RC. Comprehensive qPCR profiling of gene expression in single neuronal cells. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:118–27. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narsinh KH, et al. Single cell transcriptional profiling reveals heterogeneity of human induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1217–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI44635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raj A, van den Bogaard P, Rifkin SA, van Oudenaarden A, Tyagi S. Imaging individual mRNA molecules using multiple singly labeled probes. Nat Methods. 2008;5:877–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanna J, et al. Direct cell reprogramming is a stochastic process amenable to acceleration. Nature. 2009;462:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nature08592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maherali N, et al. Directly reprogrammed fibroblasts show global epigenetic remodeling and widespread tissue contribution. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wernig M, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–24. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fussner E, et al. Constitutive heterochromatin reorganization during somatic cell reprogramming. EMBO J. 2011;30:1778–89. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES. The mammalian epigenome. Cell. 2007;128:669–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt R, Plath K. The roles of the reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4 in resetting the somatic cell epigenome during induced pluripotent stem cell generation. Genome Biol. 2012;13:251. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang G, Zhang Y. Embryonic stem cell and induced pluripotent stem cell: an epigenetic perspective. Cell Res. 2013;23:49–69. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koche RP, et al. Reprogramming factor expression initiates widespread targeted chromatin remodeling. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramirez-Carrozzi VR, et al. A unifying model for the selective regulation of inducible transcription by CpG islands and nucleosome remodeling. Cell. 2009;138:114–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sridharan R, et al. Role of the murine reprogramming factors in the induction of pluripotency. Cell. 2009;136:364–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Breault DT, Hochedlinger K. Defining molecular cornerstones during fibroblast to iPS cell reprogramming in mouse. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:230–40. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ang YS, et al. Wdr5 mediates self-renewal and reprogramming via the embryonic stem cell core transcriptional network. Cell. 2011;145:183–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansour AA, et al. The H3K27 demethylase Utx regulates somatic and germ cell epigenetic reprogramming. Nature. 2012;488:409–13. doi: 10.1038/nature11272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costa Y, et al. NANOG-dependent function of TET1 and TET2 in establishment of pluripotency. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature11925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doege CA, et al. Early-stage epigenetic modification during somatic cell reprogramming by Parp1 and Tet2. Nature. 2012;488:652–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Y, et al. Replacement of Oct4 by Tet1 during iPSC Induction Reveals an Important Role of DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation in Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singhal N, et al. Chromatin-Remodeling Components of the BAF Complex Facilitate Reprogramming. Cell. 2010;141:943–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang G, He J, Zhang Y. Kdm2b promotes induced pluripotent stem cell generation by facilitating gene activation early in reprogramming. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:457–66. doi: 10.1038/ncb2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang T, et al. The histone demethylases Jhdm1a/1b enhance somatic cell reprogramming in a vitamin-C-dependent manner. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:575–87. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Onder TT, et al. Chromatin-modifying enzymes as modulators of reprogramming. Nature. 2012;483:598–602. doi: 10.1038/nature10953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schotta G, Ebert A, Reuter G. SU(VAR)3–9 is a conserved key function in heterochromatic gene silencing. Genetica. 2003;117:149–58. doi: 10.1023/a:1022923508198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soufi A, Donahue G, Zaret KS. Facilitators and impediments of the pluripotency reprogramming factors' initial engagement with the genome. Cell. 2012;151:994–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kagey MH, et al. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2010;467:430–5. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin C, Garruss AS, Luo Z, Guo F, Shilatifard A. The RNA Pol II Elongation Factor Ell3 Marks Enhancers in ES Cells and Primes Future Gene Activation. Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanyal A, Lajoie BR, Jain G, Dekker J. The long-range interaction landscape of gene promoters. Nature. 2012;489:109–13. doi: 10.1038/nature11279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Efe JA, et al. Conversion of mouse fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes using a direct reprogramming strategy. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:215–22. doi: 10.1038/ncb2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim J, et al. Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neural progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7838–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anokye-Danso F, et al. Highly efficient miRNA-mediated reprogramming of mouse and human somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:376–88. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maekawa M, et al. Direct reprogramming of somatic cells is promoted by maternal transcription factor Glis1. Nature. 2011;474:225–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liao B, et al. MicroRNA cluster 302–367 enhances somatic cell reprogramming by accelerating a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17359–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.235960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Subramanyam D, et al. Multiple targets of miR-302 and miR-372 promote reprogramming of human fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:443–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dang CV. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell. 2012;149:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eilers M, Eisenman RN. Myc's broad reach. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2755–66. doi: 10.1101/gad.1712408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meyer N, Penn LZ. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:976–90. doi: 10.1038/nrc2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN. Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc. Science. 1991;251:1211–7. doi: 10.1126/science.2006410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wernig M, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Jaenisch R. c-Myc is dispensable for direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:10–2. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakagawa M, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:101–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rahl PB, et al. c-Myc regulates transcriptional pause release. Cell. 2010;141:432–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nie Z, et al. c-Myc is a universal amplifier of expressed genes in lymphocytes and embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2012;151:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin CY, et al. Transcriptional amplification in tumor cells with elevated c-Myc. Cell. 2012;151:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Y, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bouchard C, Marquardt J, Bras A, Medema RH, Eilers M. Myc-induced proliferation and transformation require Akt-mediated phosphorylation of FoxO proteins. EMBO J. 2004;23:2830–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eberhardy SR, Farnham PJ. c-Myc mediates activation of the cad promoter via a post-RNA polymerase II recruitment mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48562–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carey BW, et al. Reprogramming factor stoichiometry influences the epigenetic state and biological properties of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:588–98. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stadtfeld M, et al. Aberrant silencing of imprinted genes on chromosome 12qF1 in mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;465:175–81. doi: 10.1038/nature09017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tiemann U, et al. Optimal reprogramming factor stoichiometry increases colony numbers and affects molecular characteristics of murine induced pluripotent stem cells. Cytometry A. 2011;79:426–35. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamaguchi S, Hirano K, Nagata S, Tada T. Sox2 expression effects on direct reprogramming efficiency as determined by alternative somatic cell fate. Stem Cell Res. 2011;6:177–86. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen J, et al. Rational optimization of reprogramming culture conditions for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells with ultra-high efficiency and fast kinetics. Cell Res. 2011;21:884–94. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Esteban MA, et al. Vitamin C enhances the generation of mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:71–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huangfu D, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells by defined factors is greatly improved by small-molecule compounds. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:795–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ichida JK, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of tgf-Beta signaling replaces sox2 in reprogramming by inducing nanog. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maherali N, Hochedlinger K. Tgfbeta signal inhibition cooperates in the induction of iPSCs and replaces Sox2 and cMyc. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1718–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Esteban MA, Pei D. Vitamin C improves the quality of somatic cell reprogramming. Nat Genet. 2012;44:366–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stadtfeld M, et al. Ascorbic acid prevents loss of Dlk1-Dio3 imprinting and facilitates generation of all-iPS cell mice from terminally differentiated B cells. Nat Genet. 2012;44:398–405. S1–2. doi: 10.1038/ng.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lengner CJ, et al. Derivation of pre-X inactivation human embryonic stem cells under physiological oxygen concentrations. Cell. 2010;141:872–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Greder LV, et al. Brief Report: Analysis of Endogenous Oct4 Activation during Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Reprogramming Using an Inducible Oct4 Lineage Label. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2596–601. doi: 10.1002/stem.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pennisi E, Williams N. Will Dolly send in the clones? Science. 1997;275:1415–6. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5305.1415a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hochedlinger K, Jaenisch R. Monoclonal mice generated by nuclear transfer from mature B and T donor cells. Nature. 2002;415:1035–8. doi: 10.1038/nature718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wakao S, Kitada M, Dezawa M. The elite and stochastic model for iPS cell generation: Multilineage-differentiating stress enduring (Muse) cells are readily reprogrammable into iPS cells. Cytometry A. 2012 doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamanaka S. Elite and stochastic models for induced pluripotent stem cell generation. Nature. 2009;460:49–52. doi: 10.1038/nature08180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Aoi T, et al. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse liver and stomach cells. Science. 2008;321:699–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1154884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hanna J, et al. Direct reprogramming of terminally differentiated mature B lymphocytes to pluripotency. Cell. 2008;133:250–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Seki T, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human terminally differentiated circulating T cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:11–4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Meissner A, Wernig M, Jaenisch R. Direct reprogramming of genetically unmodified fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1177–81. doi: 10.1038/nbt1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen J, et al. H3K9 methylation is a barrier during somatic cell reprogramming into iPSCs. Nat Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ng.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Boyer LA, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122:947–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meshorer E, et al. Hyperdynamic plasticity of chromatin proteins in pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Dev Cell. 2006;10:105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhu J, et al. Genome-wide Chromatin State Transitions Associated with Developmental and Environmental Cues. Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Takeuchi JK, Bruneau BG. Directed transdifferentiation of mouse mesoderm to heart tissue by defined factors. Nature. 2009;459:708–11. doi: 10.1038/nature08039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pijnappel WW, et al. A central role for TFIID in the pluripotent transcription circuitry. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature11970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mattout A, Biran A, Meshorer E. Global epigenetic changes during somatic cell reprogramming to iPS cells. J Mol Cell Biol. 2011;3:341–50. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zuo B, et al. Influences of lamin A levels on induction of pluripotent stem cells. Biol Open. 2012;1:1118–27. doi: 10.1242/bio.20121586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Suhr ST, et al. Mitochondrial rejuvenation after induced pluripotency. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Van Haute L, Spits C, Geens M, Seneca S, Sermon K. Human embryonic stem cells commonly display large mitochondrial DNA deletions. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:20–3. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hussein SM, et al. Copy number variation and selection during reprogramming to pluripotency. Nature. 2011;471:58–62. doi: 10.1038/nature09871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Laurent LC, et al. Dynamic changes in the copy number of pluripotency and cell proliferation genes in human ESCs and iPSCs during reprogramming and time in culture. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:106–18. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gore A, et al. Somatic coding mutations in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:63–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mayshar Y, et al. Identification and classification of chromosomal aberrations in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:521–31. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lister R, et al. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:68–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Doi A, et al. Differential methylation of tissue- and cancer-specific CpG island shores distinguishes human induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1350–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]