Abstract

Evidence of oxidative stress has been reported in the blood of patients with Rett syndrome (RTT), a neurodevelopmental disorder mainly caused by mutations in the gene encoding the Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Little is known regarding the redox status in RTT cellular systems and its relationship with the morphological phenotype. In RTT patients (n = 16) we investigated four different oxidative stress markers, F2-Isoprostanes (F2-IsoPs), F4-Neuroprostanes (F4-NeuroPs), nonprotein bound iron (NPBI), and (4-HNE PAs), and glutathione in one of the most accessible cells, that is, skin fibroblasts, and searched for possible changes in cellular/intracellular structure and qualitative modifications of synthesized collagen. Significantly increased F4-NeuroPs (12-folds), F2-IsoPs (7.5-folds) NPBI (2.3-folds), 4-HNE PAs (1.48-folds), and GSSG (1.44-folds) were detected, with significantly decreased GSH (−43.6%) and GSH/GSSG ratio (−3.05 folds). A marked dilation of the rough endoplasmic reticulum cisternae, associated with several cytoplasmic multilamellar bodies, was detectable in RTT fibroblasts. Colocalization of collagen I and collagen III, as well as the percentage of type I collagen as derived by semiquantitative immunofluorescence staining analyses, appears to be significantly reduced in RTT cells. Our findings indicate the presence of a redox imbalance and previously unrecognized morphological skin fibroblast abnormalities in RTT patients.

1. Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT) predominantly affects females with an incidence of 1 in 10,000–15,000 female births [1, 2]. In its typical form, affected patients exhibit various neuropsychiatric features after 6–18 months [3] of apparently normal neurodevelopment. Although phenotypical heterogeneity which determines the clinical severity of the disease is a typical feature of RTT [4], key clinical aspects include autistic traits, epileptic seizures, breathing abnormalities, gait ataxia, stereotypies, and loss of finalistic hands use [3]. Mutations in the gene encoding the Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) account for approximately 90% of cases with typical RTT and are almost exclusively de novo [4]. Nine most frequent mutations comprise more than 3/4 of all the reported pathogenic ones [5]; in addition, MECP2 gene mutations are usually categorized as missense or truncating, including nonsense, frameshift, and large deletions, according to the type of sequence change.

Oxidative stress (OS) indicates a combination of events resulting in a damage to biological molecules due to an imbalance between cellular antioxidant defences and free radicals production. OS appears to be involved in a large number of human diseases, including cancer [6–8] neurodegenerative diseases [9, 10] and inflammatory bowel disease [11]. Furthermore, cumulating evidence suggests the presence of a redox imbalance in autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), a condition with a high social impact due to the explosive increase in its prevalence over the last four decades [12–18]. Our group and other laboratories have reported enhanced OS markers levels in plasma and erythrocytes from patients with RTT, thus suggesting the presence of a systemic OS in the disease. However, to date, it is unclear not only why, but also when, and where this OS derangement may occur [19–26].

In particular to date, little is known regarding the oxidant-antioxidant status in RTT cellular systems and its possible relationship with the morphological phenotype. Here, we investigated the levels of different OS markers (F2-IsoPs, F4-NeuroPs, NPBI, and 4-HNE PAs) and glutathione in primary skin fibroblasts from patients with typical RTT, as well as possible changes in the cellular/intracellular structure and/or qualitative changes in the synthesized collagen.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

A total of 16 female patients with typical RTT (mean age: 13.06 ± 6.5), as well as 8 healthy female controls of comparable age (mean age: 13.2 ± 6.8), participated in the study. Skin biopsies from the control group were obtained from a skin biobank by selecting subjects without diagnosed skin or collagen diseases (responsibility: Joussef Hayek).

All patients were consecutively admitted to the Child Neuropsychiatry Unit of the University Hospital of Siena (Head: Joussef Hayek). For all patients the MECP2 mutation was demonstrated (mutation categories: missense mutation n = 8; early truncating mutation n = 6; late truncating mutation n = 2), and a clinical severity score was calculated using the previously reported scaling system [27] (mean severity score: 15.9 ± 6.47; range: 5.0–28.0). All the examined subjects were on a typical Mediterranean diet.

A 3 mm skin punch biopsy was performed after obtained written informed consent of either the parents or the legal tutors of the patients (responsibility: Joussef Hayek). Biopsies from control subject were performed in the Dermatology Unit of the University Hospital of Siena. The study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese.

2.2. Fibroblasts Isolation and Culture

Following informed consent signature, skin biopsies (about 3-4 mm3) were performed using the Punch Biopsy procedure. Fibroblasts were isolated and cultured with standard protocols [28]. Cells were grown in DMEM (Biochrom), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 until 80–90% confluence and routinely passed by trypsin-EDTA (Irvine Scientific).

Cells for analysis were seeded onto 100 mm tissue culture plates (for NPBI and IsoP evaluations) and 12-well plates (for 4-HNE PAs and GSH/GSSG ratio) containing the indicated medium formulations. Fibroblasts at low passage were employed for the analysis.

At confluence, the cells were scraped, transferred in a tube, and washed twice with ice-cold PBS pH 7.4. Cells were then centrifuged at 600 g for 10 min and the pellet resuspended in a final volume of 2 mL PBS.

2.3. Nonprotein Bound Iron (NPBI)

Nonprotein bound iron was determined as desferoxamine- (DFO-) chelatable free iron (DFO-iron complex, ferrioxamine). DFO 25 μM was added to 1 mL of cell suspension to obtain a final concentration of 25 μM DFO and the cells were ruptured by the addition of 1 mL water, freeze-thawing, and sonication. The samples were then ultrafiltered in centrifuge filter devices (VIVASPIN 4, Sartorius Stedim Biotech GmbH, Goettingen, Germany) with a 30 kDa molecular weight cutoff and the ultrafiltrate was stored at −20°C until analysis. The DFO excess was removed by silica (Silicagel 25–40 μm; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) column chromatography (Varian Inc., CA, USA). The DFO-iron complex was determined by HPLC and the detection wavelength was 229 nm [29].

2.4. Total (Sum of Free Plus Esterified) F2-Isoprostanes and F4-Neuroprostanes Determinations

Butylated hydroxytoluene was added to 900 μL of cell suspension as an antioxidant to obtain a final concentration of 90 μM and the samples were frozen at −70°C until analysis. All isoprostane and neuroprostane determinations were carried out by gas chromatography/negative ion chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry (GC/NICI-MS/MS) analysis after solid phase extraction and derivatization steps. F2-Isoprostanes and F4-neuroprostanes levels were normalized for the cell protein content.

2.5. Solid Phase Extraction and Derivatization Procedures

At the time of the determination, the samples were sonicated by ultrasound treatment for 30 seconds and then purified as previously reported [29]. Briefly, aqueous KOH (1 mM, 450 μL) was added to the cellular suspension. After incubation at 45°C for 45 min, the pH was adjusted to 3 by adding HCl (1 mM, 450 μL). Each sample was spiked with tetradeuterated prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α-d4) (500 pg in 50 μL of ethanol), as an internal standard, and ethyl acetate (10 mL) was added to extract total lipids by vortex-mixing and centrifugation at 1,000 g for 5 min at room temperature. The total lipid extract was applied onto an NH2 cartridge and the isoprostanes in the final eluates were derivatized. The carboxylic group was derivatized as the pentafluorobenzil ester whereas the hydroxyl groups were converted to trimethylsilyl ethers [30].

2.6. F2-Isoprostane GC/NICI-MS/MS

Measured ions were the product ions at m/z 299 and m/z 303 derived from the [M−181]− precursor ions (m/z 569 and m/z 573) produced from 15-F2t-IsoPs and the tetradeuterated derivative of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α-d4), respectively [29, 30].

2.7. F4-NeuroPs GC/NICI-MS/MS

Measured ions were the product ions at m/z 323 and m/z 303 derived from the [M−181]− precursor ions (m/z 593 and m/z 573) produced from oxidized DHA and the tetradeuterated derivative of PGF2α, respectively [29, 31].

2.8. Intracellular Redox Status

Usually, cellular glutathione (GSH) exists mainly in the reduced form whereas the oxidized disulfide form (GSSG) is present in small amounts. The GSH/GSSG ratio is often taken as an indicator of cellular redox status. Intracellular GSH and GSSG levels were determined by an enzymatic recycling procedure according to Tietze [32] and Baker et al. [33]. The SH group of the molecule reacts with 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), producing a yellow-coloured 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid (TNB), and the disulfide is reduced by NADPH in the presence of GSH reductase. GSSG was determined after derivatization step of GSH by reaction with 2-vinylpyridine. The rate of TNB formation was monitored at 420 nm. GSH and GSSG levels were normalized for protein content.

At confluence, after medium removal, cultured fibroblasts were washed twice with PBS pH 7.4 and treated with 5% 5-sulfosalicylic acid (w/v) solution for 30 min at 4°C. The acidic extracts were stored at −70°C until the assay. The protein extracts were obtained by cellular lysis with NaOH 0.1 M.

2.9. 4-HNE Protein Adducts

4-HNE PAs are markers of protein oxidation due to aldehyde binding from lipid peroxidation sources [34], determined by Western blot technique. Cell proteins (30 μg protein, as determined by using Bio-Rad protein assay; BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) were resolved on 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels (Lonza Group Ltd., Switzerland) and transferred onto a hybond ECL nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Milan, Italy). After blocking in 3% nonfat milk (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA), the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with goat polyclonal anti 4-HNE adduct antibody (cod. AB5605; Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). Following washes in TBS Tween and incubation with specific secondary antibody (mouse anti-goat horseradish peroxidase-conjugated, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated with ECL reagents (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) for 1 min. The bands were visualized by autoradiography. Quantification of the relevant bands was performed by digitally scanning the Amersham Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Milan, Italy) and measuring immunoblotting image densities with ImageJ software.

2.10. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Cultured fibroblasts were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer pH 7.2 (CB) for 3 hours at 4°C. After a rinse in CB, the material was postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in CB for 2 hours at 4°C, dehydrated in a graded series of alcohol, embedded in Araldite resins, and polymerized in oven for 48 hours at 60°C. Sixty nm thin sections, obtained with a Reichert ultramicrotome, were routinely stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed with a TEM Fei Tecnai G2 spirit at 100 Kv.

2.11. Immunofluorescence Double Staining

The localization of two main type of collagen synthetized by skin fibroblasts was evaluated by an immunofluorescence assay. Primary human fibroblasts, grown on glass coverslips at a density of 2 × 104 cells/cm2, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4°C. After fixation and permeabilization for 10 min at room temperature with 0.1% Triton X-100, cells were blocked for 30 min at room temperature with PBS containing 5% BSA. Fibroblasts were then incubated with primary antibodies for collagen I and collagen III (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL, USA) in PBS with 1% BSA at 4°C overnight. After washing, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 568 and Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies Corporation, Monza, Italy) for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with 1 μg/mL DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich S.r.l., Milan, Italy) for 1 min. Coverslips were mounted onto glass slides using antifade mounting medium 1,4-diazabicyclooctane in glycerine (DABCO). Observations and photographs were made with a Leitz Aristoplan light microscope (Leica, Milan, Italy) equipped with fluorescence apparatus. Incubation in primary antibodies was omitted in negative controls.

The relative intensity of fluorescence was measured in regions of interest (ROI) by using the Software LEICA AF6000 (Leica Microsystems-Germany).

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges or means ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were evaluated by the nonparametric Mann-Whitney rank sum test, Wilcoxon rank test, or Kruskal-Wallis test analysis of variance (ANOVA), as appropriate. The MedCalc ver. 12.1.4 statistical software package (MedCalc. Software, Mariakerke, Belgium) was used for data analysis. Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered as significant.

3. Results

3.1. Cell Oxidant and Antioxidant Status

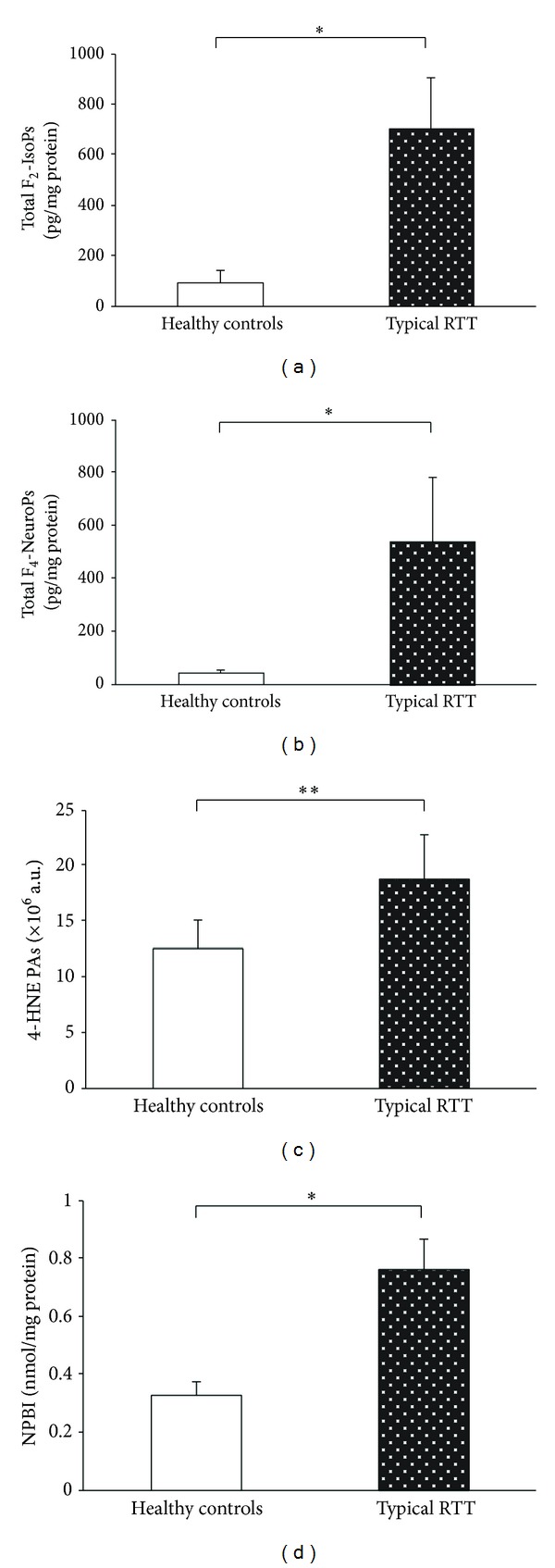

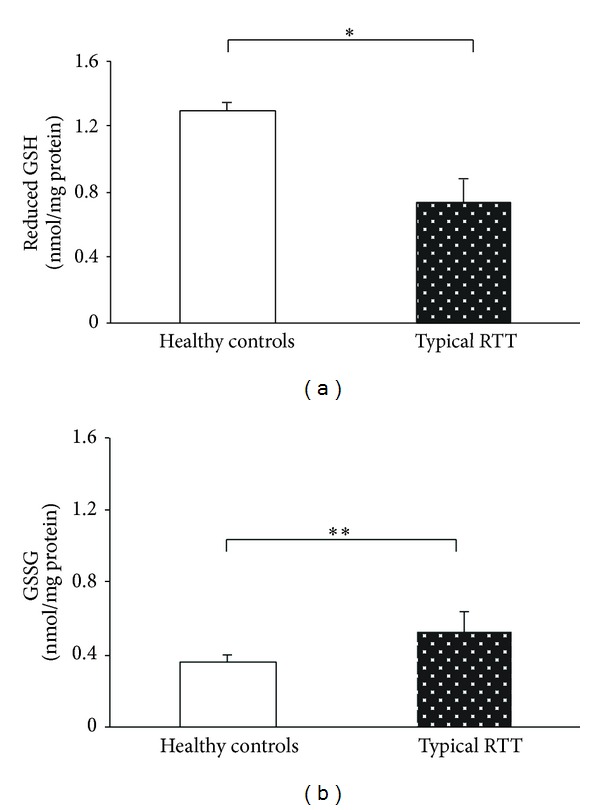

Biochemical signs of lipid and protein oxidative damage, together with the antioxidant cellular defense, were evaluated in skin fibroblasts from RTT and healthy control subjects. Increased lipid oxidative damage was evidenced as indicated by increased levels of total (i.e., sum of free and esterified form) F2-IsoPs (7.5-folds) and F4-NeuroPs (12-folds), both deriving from membrane polyunsaturated fatty acids, that is, arachidonic (AA) and docosahexaenoic (DHA) acid, respectively (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). Biochemical signs of protein oxidative damage consequent to a lipid peroxidation event were indicated by increased (1.48-folds) 4-HNE PAs levels for which a significant increase was also detected (Figure 1(c)). Oxidative damage was concomitant to an imbalance in the principal antioxidant cytoplasmic agent in so far as a significant reduction (−43.6%) in cellular GSH, a significant increase (1.44-folds) of GSSG (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)), and a significant reduction (−3.05 folds) of GSH/GSSG ratio were reported. Lipid peroxidation events in RTT skin fibroblasts were found to be related to the levels of NPBI, a prooxidant agent. NPBI was significantly increased (2.3-folds) (Figure 1(d)), with significant positive correlations observed between NPBI and total cellular F4-NeuroPs (Rho = 0.84, P = 0.001) and NPBI versus total cellular F2-IsoPs (Rho = 0.69, P = 0.019). No significant relationships between each of the investigated molecules (i.e., F2-IsoPs, F4-NeuroPs, 4-HNE Pas, GSH and GSSG) and the MECP2 mutation categories were observed (P value range: 0.461–0.981).

Figure 1.

Increased levels of total (i.e., sum of free and esterified form) F2-IsoPs, total F4-NeuroPs, 4-HNE PAs, and NPBI in RTT skin fibroblast as compared to the control cells. *P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0013. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. Legend: F2-IsoPs, F2-isoprostanes; F4-NeuroPs, F4-neuroprostanes; 4-HNE PAs, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal protein adducts; NPBI, nonprotein bound iron.

Figure 2.

Significant reduction in cellular GSH and significant increase of GSSG in RTT skin fibroblast as compared to control cells. *P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0033. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. Legend: GSH reduced glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione.

3.2. Cell Morphology Study

To evaluate the effect, if present, of the oxidant/antioxidant imbalance evidenced in RTT fibroblasts, the physiological cellular condition was evaluated by observation of two key typical features: the morphology and the collagen distribution.

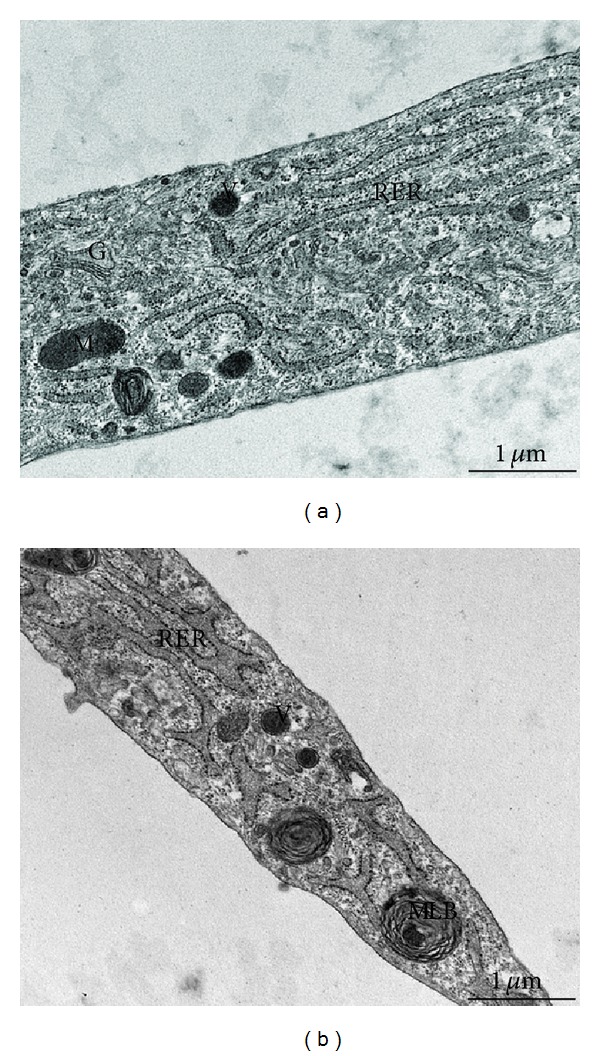

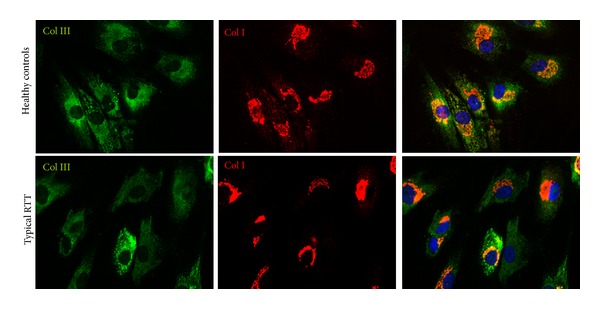

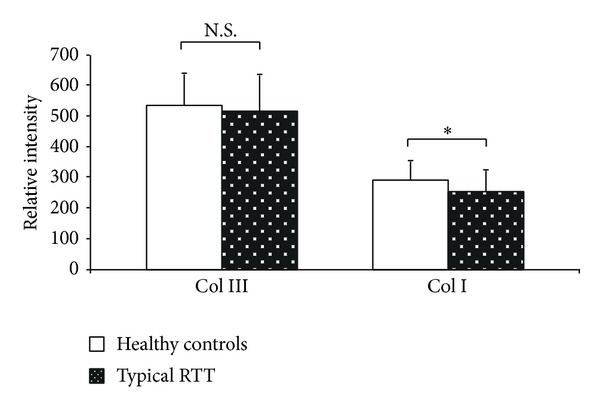

At transmission electron microscope significant ultrastructural differences between control and RTT fibroblasts were observed. In particular, a marked dilation of the rough endoplasmic reticulum cisternae was detectable in the skin RTT fibroblasts, along with evidence of cytoplasmic multilamellar bodies (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). Immunofluorescence double staining showed a reduced degree of colocalization of type III and type I collagen in RTT skin fibroblasts when compared to control cells. Staining for type I collagen was found to be more evident in RTT cells, where perinuclear granules were also detectable (Figure 4). Likewise, in these same cells, fluorescence relative intensity for type I collagen was significantly reduced (P = 0.00997) (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscopy of control (a) and RTT (b) fibroblasts cultures. Skin fibroblasts, either from control subjects or RTT patients, show a flattened morphology with extensive tapering cytoplasmic processes. An euchromatic and oval-shaped nucleus was present in central position of the cells, with clumps of heterochromatin next to the nuclear envelope. The cytoplasm contains many vesicles with variable electron density, a prominent Golgi complex, and mitochondria. Rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) cisternae in RTT fibroblasts appear more dilated than in control. Some large multilamellar bodies (MLB) are frequently detectable in the cytoplasm of the RTT fibroblast cells. (G) Golgi complex, (M) mitochondrion, and (V) vesicle. Bar = 1 μm.

Figure 4.

Double immunofluorescence staining shows the localization of type I collagen (central column, red color) and type III collagen (left column, green color). Images are merged in the right panel and the yellow color indicates overlap of the staining. The colocalization of types I and III collagen is reduced in RTT skin fibroblasts. Legend: Col I, type I collagen; Col III, type III collagen.

Figure 5.

Relative intensity of fluorescence for types I and type III collagen in RTT and control skin fibroblasts. Software LEICA AF6000 (Leica Microsystems-Germany). Data are expressed as median ± semiinterquartile range *P = 0.0062; N.S.: no significant difference (P = 0.4361). Legend: Col I, type I collagen; Col III, type III collagen.

4. Discussion

Our findings demonstrate, for the first time, the presence of an extensive redox imbalance in primary skin fibroblasts cultures obtained from patients with RTT by adding new evidence to the concept of an OS imbalance as key phenotypical features of MeCP2 deficiency in RTT. Earlier clues for an abnormal OS balance in RTT patients harbouring MECP2 gene mutations are to date limited to plasma and erythrocytes samples [26, 35]. Although enhanced plasmatic OS markers levels suggest a systemic OS status, to date no indications are present in order to infer what tissues/cellular systems other than blood could be potentially damaged by the OS imbalance in RTT. A preliminary suggestion that an oxidative process should occur at the cellular level was contained in our recent study where oxidative posttranslational modifications on SRB1 receptor in primary fibroblast cultures were observed [36]. Fibroblasts have been used in the RTT scientific research to evaluate gene mutation and epigenetic process [37], differentiation to induced pluripotent stem (iPS) [38], cellular response subsequent to MECP2 mutation [39], reduction of stathmin-like 2 [40], and the effects of NB54 and other rationally designed aminoglycoside derivatives as potential therapeutic agents for nonsense MECP2 mutations in RTT [41]. Fibroblasts have been extensively employed to investigate OS in different pathophysiological processes such as genetic neurodegenerative diseases [42], Parkinson's disease [43], aging [44], and response to etiological agents [45, 46]. Moreover, lipid peroxidation events are known to be relevant to the fibroblast function, as relationship between mechanotransduction and lipid metabolites has been previously investigated in keloids [47].

The biochemical markers so far employed for measuring OS are not to be considered as equal in terms of the conveyed information. In particular, F2-IsoPs, the gold standard molecules for the OS in vivo evaluation [35, 48], are the end-products of arachidonic acid (AA) oxidation, a polyunsaturated fatty acid abundant in both brain grey and white matter. On the other hand, F4-NeuroPs are the oxidative end-products of docosahexanoic acid (DHA), abundant in neuronal membranes [49]. NPBI is a prooxidant factor, associated with hypoxia, hemoglobin oxidation, and subsequent heme iron release [50].

Our data demonstrate that both AA and DHA undergo significant oxidation in RTT fibroblasts. Although DHA is known to be particularly abundant in neuronal membranes, this fatty acid represents a normal constituent of all cell membranes. In particular, human fibroblasts are able to synthetize DHA [51] and incorporate it in their membrane phospholipids [52]. Furthermore, variations of the DHA content in the membrane of fibroblasts have been implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders, with lowered levels evidenced in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [53]. Our results indicate an increased oxidation of DHA in RTT fibroblasts, thus underlying an increased susceptibility of these cells to oxidative damage. This process, in turn, could contribute to changes in the fatty acid composition of membranes with consequent cellular damage.

4HNE, which is formed from arachidonic acid or other unsaturated fatty acids following free radical attack, can bind, by Michael addition, to proteins, particularly, to cysteine, histidine, or lysine residues. Thanks to its ability to form adducts to the proteins, 4HNE is not only considered as a reliable marker of OS, but also has a biological impact by changing protein function [34]. Our findings of increased 4HNE-PAs can be considered as a long-term consequence of enhanced lipid peroxidation, further contributing to cellular damage.

Glutathione, the main cellular antioxidant defence, preventing the damage to key cellular components induced by reactive oxygen species, exists in both reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) states. In its reduced state, the thiol group of cysteine is able to donate a reducing equivalent (H+ + e−) to other unstable molecules, such as ROS, whereas in donating an electron, glutathione itself becomes reactive but is ready to react with another reactive glutathione to form GSSG.

Our reported results of decreased GSH levels and GSH/GSSG ratio indicate a reduced antioxidant defence in RTT cells and suggest that oxidative events are likely to be chronic, thus determining a consumption of glutathione in its reduced form. An alternative explanation could be that the MECP2 mutation-harboring cells may have coexisting defects in the synthesis and/or recycling of glutathione, thus leading to an uncontrolled free radicals action. Of course, further study is needed in order to clarify this point.

Overall, our data indicate that a significant oxidation of DHA, the precursor acid for F4-NeuroPs, and AA, precursor of F2-IsoPs, likely triggered by NPBI, occurs in skin fibroblasts of patients with MECP2 mutation and clinical RTT and confirm the biological relevance of such key mediators of lipid peroxidation.

Skin dermis is known to be consisting of 80% collagen type I, with its remaining fraction being made mostly of collagen type III [54]. In this context, the fibroblast shows a pivotal role for collagen production, [55].

Besides being a major component of the extracellular matrix in a variety of internal organs and skin in adults, type III collagen is critical for fibrillogenesis in the development of apparatus such as skin and cardiovascular system [56, 57]. Overall in such tissues, type III collagen is colocalized, within the same fibril, with the most abundant member of the family, type I collagen, and regulates the diameter of type I collagen fibrils, which have to meet the physiological requirements of different tissues at different developmental stages [54, 58–62].

The reported ultrastructural changes are to be considered as a new finding to be added to the mitochondrial changes previously reported in RTT skin fibroblasts [63]. Since no abnormalities in wound repair and/or healing have been reported in RTT patients, these ultrastructural features are to be considered as subclinical characteristics of the disease. Marked dilation of the rough endoplasmic reticulum cisternae and cytoplasmic multilamellar bodies were observed for the first time in this study. Dilated rough endoplasmic reticulum cisternae can be considered as a nonspecific adaptive response due to either increased secretory activity or as the result of the cellular response to noxae of different nature [64, 65]. On the other hand, the presence of multilamellar bodies could be interpreted as an expression of cellular damage. In particular, those structures suggest the occurrence of autophagy phenomena of unclear pathogenesis [66].

A condition of oxidative stress has been previously reported in aging skin [67]. Skin aging is known to be mainly due to fragmentation/loss of type I collagen fibrils, conferring strength, and resiliency in association with metalloproteinase activation, involved in type I collagen degradation [68]. Although, no evidence of wound healing alterations or derma laxity has not been reported in RTT, an accelerated ageing process is known to occur in the affected patients. Our results suggest the occurrence of a possible reduction in type I collagen, a feature of aging skin, while they show a clear redox imbalance in RTT skin fibroblasts. Therefore, it is conceivable that a premature skin aging may occur in RTT patients, a hypothesis which is in line with prior evidence of premature senescence phenomena in the disease [69–72].

Given that OS is known to be a major determinant of aging [73, 74], it is conceivable that aging phenomena in RTT, including skin fibroblasts morphological changes, may be caused through OS mechanisms.

5. Conclusion

Our study demonstrates for the first time the occurrence of lipid peroxidation in RTT fibroblasts, together with a reduced antioxidant cellular defense with a major impact on cell morphology. We speculate about a possible functional involvement of these changes in the skin fibroblasts of RTT patients which must be taken into account when evaluating this cellular model of the disease. Our findings suggest that OS is a generalized phenomenon in RTT, thus affecting cellular systems and tissues apparently unrelated to the central nervous system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Grant no. RF-TOS-2008-1225570—Bando Malattie Rare to AR. The present research project has been mainly funded by the Italian Health Ministry and Tuscan Region. This research is dedicated to all the Rett girls and their families. The authors thank Dr. Pierluigi Tosi, Dr. Silvia Briani, and Dr. Roberta Croci from the Administrative Direction of the Azienda Ospedaliera Senese for continued support to our studies and for prior purchasing of the gas spectrometry instrumentation. They also thank professional singer Matteo Setti for his artistic contributions to the exploration of Rett syndrome and his many charity concerts dedicated to the Rett girls and their families.

Abbreviations

- 4-HNE:

4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal

- 4-HNE PAs:

4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal protein adducts

- AA:

Arachidonic acid

- DHA:

Docosahexaenoic acid

- F2-IsoPs:

F2-isoprostanes

- F4-NeuroPs:

F4-neuroprostanes

- GSH:

Reduced glutathione

- GSSG:

Oxidized glutathione

- IsoPs:

Isoprostanes

- MECP2:

Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2—human gene

- MeCP2:

Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2—human protein

- NPBI:

Nonprotein bound iron

- OS:

Oxidative stress

- PUFAs:

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- ROS:

Reactive Oxygen Species

- RTT:

Rett syndrome

- TEM:

Transmission electron microscopy.

Disclosure

Cofirsts: Cinzia Signorini, Silvia Leoncini, Claudio De Felice, and Alessandra Pecorelli. Colasts: Lucia Ciccoli, Alessandra Renieri, and Joussef Hayek.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

The conception of the paper was performed by Cinzia Signorini, Claudio De Felice, Silvia Leoncini, Lucia Ciccoli, Alessandra Renieri, and Joussef Hayek. The experimental design was performed by Cinzia Signorini and Claudio De Felice. MECP2 mutation determinations were performed by Ilaria Meloni, Francesca Ariani, Francesca Mari, Sonia Amabile, and Alessandra Renieri. Clinical assessement was performed by Joussef Hayek, Claudio De Felice, and Alessandra Renieri. Skin biopsies were performed by Joussef Hayek. Samples were prepared by Cinzia Signorini, Silvia Leoncini, Alessandra Pecorelli, Gloria Zollo, Giuseppe Belmonte, Mariangela Gentile, Eugenio Paccagnini, Sonia Amabile, and Ilaria Meloni. NPBI assays were performed by Silvia Leoncini. Isoprostanes and neuroprostanes assays were performed by Cinzia Signorini, Thierry Durand, and Jean-Marie Galano. 4-HNE-PAs assays were carried out by Alessandra Pecorelli, and Giuseppe Valacchi. Gluthatione assays were carried out by Silvia Leoncini and Gloria Zollo. Immunocytochemistry was performed by Giuseppe Belmonte and Alessandra Pecorelli. TEM was done by Eugenio Paccagnini and Mariangela Gentile. Data analysis was done by Claudio De Felice, Cinzia Signorini, and Silvia Leoncini. All the authors equally contributed in data interpretation, paper drafting, and paper approval.

References

- 1.Hagberg B, Aicardi J, Dias K, Ramos O. A progressive syndrome of autism, dementia, ataxia, and loss of purposeful hand use in girls: rett’s syndrome: report of 35 cases. Annals of Neurology. 1983;14(4):471–479. doi: 10.1002/ana.410140412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bienvenu T, Philippe C, De Roux N, et al. The incidence of rett syndrome in France. Pediatric Neurology. 2006;34(5):372–375. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagberg B. Clinical manifestations and stages of Rett syndrome. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2002;8(2):61–65. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl—CpG—binding protein 2. Nature Genetics. 1999;23(2):185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christodoulou J, Grimm A, Maher T, Bennetts B. RettBASE: the IRSA MECP2 variation database-a new mutation database in evolution. Human Mutation. 2003;21(5):466–472. doi: 10.1002/humu.10194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and cancer: have we moved forward? The Biochemical Journal. 2007;401(1):1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halliwell B. Free radicals and antioxidants—quo vadis? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2011;32(3):125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halliwell B. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. 4th edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aluise CD, Robinson RAS, Cai J, Pierce WM, Markesbery WR, Butterfield DA. Redox proteomics analysis of brains from subjects with amnestic mild cognitive impairment compared to brains from subjects with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: insights into memory loss in MCI. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2011;23(2):257–269. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enciu A-M, Gherghiceanu M, Popescu BO. Triggers and effectors of oxidative stress at blood-brain barrier level: relevance for brain ageing and neurodegeneration. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2013;2013:12 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/297512.297512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brazil JC, Louis NA, Parkos CA. The role of polymorphonuclear leukocyte trafficking in the perpetuation of inflammation during inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2013;19(7):1556–1565. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281f54e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghezzo A, Visconti P, Abruzzo PM, et al. Oxidative stress and erythrocyte membrane alterations in children with autism: correlation with clinical features. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066418.e66418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciccoli L, De Felice C, Paccagnini E, et al. Erythrocyte shape abnormalities, membrane oxidative damage, and β-actin alterations: an unrecognized triad in classical autism. Mediators of Inflammation. 2013;2013:11 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/432616.432616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pecorelli A, Leoncini S, De Felice C, et al. Non-protein-bound iron and 4-hydroxynonenal protein adducts in classic autism. Brain and Development. 2013;35(2):146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chauhan A, Audhya T, Chauhan V. Brain region-specific glutathione redox imbalance in autism. Neurochemical Research. 2012;37(8):1681–1689. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James SJ, Rose S, Melnyk S, et al. Cellular and mitochondrial glutathione redox imbalance in lymphoblastoid cells derived from children with autism. FASEB Journal. 2009;23(8):2374–2383. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baio J. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(3):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James SJ, Cutler P, Melnyk S, et al. Metabolic biomarkers of increased oxidative stress and impaired methylation capacity in children with autism. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;80(6):1611–1617. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grillo E, Lo Rizzo C, Bianciardi L, et al. Revealing the complexity of a monogenic disease: Rett syndrome exome sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056599.e56599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Großer E, Hirt U, Janc OA, et al. Oxidative burden and mitochondrial dysfunction in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neurobiology of Disease. 2012;48(1):102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Felice C, Signorini C, Durand T, et al. Partial rescue of Rett syndrome by ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) oil. Genes and Nutrition. 2012;7(3):447–458. doi: 10.1007/s12263-012-0285-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciccoli L, De Felice C, Paccagnini E, et al. Morphological changes and oxidative damage in Rett Syndrome erythrocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: General Subjects. 2012;1820(4):511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leoncini S, De Felice C, Signorini C, et al. Oxidative stress in Rett syndrome: natural history, genotype, and variants. Redox Report. 2011;16(4):145–153. doi: 10.1179/1351000211Y.0000000004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Felice C, Signorini C, Durand T, et al. F2-dihomo-isoprostanes as potential early biomarkers of lipid oxidative damage in Rett syndrome. Journal of Lipid Research. 2011;52(12):2287–2297. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P017798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Felice C, Ciccoli L, Leoncini S, et al. Systemic oxidative stress in classic Rett syndrome. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2009;47(4):440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Felice C, Signorini C, Leoncini S, et al. The role of oxidative stress in Rett syndrome: an overview. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1259(1):121–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renieri A, Mari F, Mencarelli MA, et al. Diagnostic criteria for the Zappella variant of Rett syndrome (the preserved speech variant) Brain and Development. 2009;31(3):208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dracopoli N, Haines J, Korf B, et al. Current Protocols in Human Genetics. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Signorini C, Ciccoli L, Leoncini S, et al. Free iron, total F2-isoprostanes and total F4-neuroprostanes in a model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: neuroprotective effect of melatonin. Journal of Pineal Research. 2009;46(2):148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Signorini C, Comporti M, Giorgi G. Ion trap tandem mass spectrometric determination of F2-isoprostanes. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2003;38(10):1067–1074. doi: 10.1002/jms.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Signorini C, De Felice C, Leoncini S, et al. F4-neuroprostanes mediate neurological severity in Rett syndrome. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2011;412(15-16):1399–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tietze F. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Analytical Biochemistry. 1969;27(3):502–522. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker MA, Cerniglia GJ, Zaman A. Microtiter plate assay for the measurement of glutathione and glutathione disulfide in large numbers of biological samples. Analytical Biochemistry. 1990;190(2):360–365. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90208-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valacchi G, Pecorelli A, Signorini C, et al. 4HNE protein adducts in autistic spectrum disorders: rett syndrome and autism. In: Patel VB, Preedy VR, Martin CR, editors. Comprehensive Guide to Autism. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2014. pp. 2667–2687. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Signorini C, De Felice C, Durand T, et al. Isoprostanes and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal: markers or mediators of disease? focus on Rett syndrome as a model of autism spectrum disorder. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2013;2013:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/343824.343824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sticozzi C, Belmonte G, Pecorelli A, et al. Scavenger receptor B1 post-translational modifications in Rett syndrome. FEBS Letters. 2013;587(14):2199–2204. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyake K, Yang C, Minakuchi Y, et al. Comparison of genomic and epigenomic expression in monozygotic twins discordant for rett syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066729.e66729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amenduni M, De Filippis R, Cheung AYL, et al. IPS cells to model CDKL5-related disorders. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;19(12):1246–1255. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delépine C, Nectoux J, Bahi-Buisson N, Chelly J, Bienvenu T. MeCP2 deficiency is associated with impaired microtubule stability. FEBS Letters. 2013;587(2):245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nectoux J, Florian C, Delepine C, et al. Altered microtubule dynamics in Mecp2-deficient astrocytes. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2012;90(5):990–998. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vecsler M, Ben Zeev B, Nudelman I, et al. Ex vivo treatment with a novel synthetic aminoglycoside NB54 in primary fibroblasts from Rett syndrome patients suppresses MECP2 nonsense mutations. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020733.e20733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandi C, Sandi M, Jassal H, et al. Generation and characterisation of friedreich ataxia YG8R mouse fibroblast and neural stem cell models. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089488.e89488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferretta A, Gaballo A, Tanzarella P, et al. Effect of resveratrol on mitochondrial function: implications in parkin-associated familiar Parkinson's disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1842(7):902–915. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boesten DM, de Vos-Houben JM, Timmermans L, den Hartog GJ, Bast A, Hageman GJ. Accelerated aging during chronic oxidative stress: a role for PARP-1. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2013;2013:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/680414.680414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang G-Y, Zhang C-L, Liu X-C, Qian G, Deng D-Q. Effects of cigarette smoke extracts on the growth and senescence of skin fibroblasts in vitro. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2013;9(6):613–623. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang H, Liu C, Yang D, Zhang H, Xi Z. Comparative study of cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and genotoxicity induced by four typical nanomaterials: the role of particle size, shape and composition. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2009;29(1):69–78. doi: 10.1002/jat.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang C, Ogawa R. Roles of lipid metabolism in keloid development. Lipids in Health and Disease. 2013;12(1, article 60) doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-12-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Musiek ES, Yin H, Milne GL, Morrow JD. Recent advances in the biochemistry and clinical relevance of the isoprostane pathway. Lipids. 2005;40(10):987–994. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roberts LJ, II, Fessel JP, Davies SS. The biochemistry of the isoprostane, neuroprostane, and isofuran pathways of lipid peroxidation. Brain Pathology. 2005;15(2):143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ciccoli L, Leoncini S, Signorini C, Comporti M. Iron and erythrocytes: physiological and pathophysiological aspects. In: Valacchi G, Davis P, editors. Oxidants in Biology. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008. pp. 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore SA, Hurt E, Yoder E, Sprecher H, Spector AA. Docosahexaenoic acid synthesis in human skin fibroblasts involves peroxisomal retroconversion of tetracosahexaenoic acid. Journal of Lipid Research. 1995;36(11):2433–2443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown ER, Subbaiah PV. Differential effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on human skin fibroblasts. Lipids. 1994;29(12):825–829. doi: 10.1007/BF02536249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahadik SP, Mukherjee S, Horrobin DF, Jenkins K, Correnti EE, Scheffer RE. Plasma membrane phospholipid fatty acid composition of cultured skin fibroblasts from schizophrenic patients: comparison with bipolar patients and normal subjects. Psychiatry Research. 1996;63(2-3):133–142. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(96)02899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Epstein EH, Jr., Munderloh NH. Isolation and characterization of CNBr peptides of human [α1(III)]3 collagen and tissue distribution of [α1(I)]2α2 and [α1(III)]3 collagens. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1975;250(24):9304–9312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Min L-J, Cui T-X, Yahata Y, et al. Regulation of collagen synthesis in mouse skin fibroblasts by distinct angiotensin II receptor subtypes. Endocrinology. 2004;145(1):253–260. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olsen BR. The roles of collagen genes in skeletal development and morphogenesis. Experientia. 1995;51(3):194–195. doi: 10.1007/BF01931087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong RS, Follis FM, Shively BK, Wernly JA. Osteogenesis imperfecta and cardiovascular diseases. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1995;60(5):1439–1443. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00706-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vuorio E, de Crombrugghe B. The family of collagen genes. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1990;59:837–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.004201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piez K, Reddi A, editors. Extracellular Matrix Biochemistry. New York, NY, USA: Elsevier; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mayne R, Burgeson R, editors. Structure and Function of Collagen Types. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bornstein P, Sage H. Structurally distinct collagen types. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1980;49:957–1003. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.004521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fleischmajer R, Olsen BR, Timpl R, Perlish JS, Lovelace O. Collagen fibril formation during embryogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1983;80(11):3354–3358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.11.3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cardaioli E, Dotti MT, Hayek G, Zappella M, Federico A. Studies on mitochondrial pathogenesis of Rett syndrome: ultrastructural data from skin and muscle biopsies and mutational analysis at mtDNA nucleotides 10463 and 2835. Journal of Submicroscopic Cytology and Pathology. 1999;31(2):301–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stabellini G, Berti G, Calastrini C, et al. Experimental model for studying the effects of 2-ethylhexyl-phthalate and dialysate on connective tissue. The International Journal of Artificial Organs. 2000;23(5):305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ellender G, Ham KN. Connective tissue responses to some heavy metals. III silver and dietary supplements of ascorbic acid. Histology and ultrastructure. British Journal of Experimental Pathology. 1989;70(1):21–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Korkhov VM. GFP-LC3 labels organised smooth endoplasmic reticulum membranes independently of autophagy. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2009;107(1):86–95. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fisher GJ, Quan T, Purohit T, et al. Collagen fragmentation promotes oxidative stress and elevates matrix metalloproteinase-1 in fibroblasts in aged human skin. American Journal of Pathology. 2009;174(1):101–114. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xia W, Hammerberg C, Li Y, et al. Expression of catalytically active matrix metalloproteinase-1 in dermal fibroblasts induces collagen fragmentation and functional alterations that resemble aged human skin. Aging Cell. 2013;12(4):661–671. doi: 10.1111/acel.12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hagberg B. Rett syndrome: long-term clinical follow-up experiences over four decades. Journal of Child Neurology. 2005;20(9):722–727. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200090401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Halbach N, Smeets E, Steinbusch C, Maaskant M, van Waardenburg D, Curfs L. Aging in Rett syndrome: a longitudinal study. Clinical Genetics. 2013;84(3):223–229. doi: 10.1111/cge.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ward CS, Arvide EM, Huang T-W, Yoo J, Noebels JL, Neul JL. MeCP2 is critical within HoxB1-derived tissues of mice for normal lifespan. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(28):10359–10370. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0057-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Squillaro T, Alessio N, Cipollaro M, et al. Reduced expression of MECP2 affects cell commitment and maintenance in neurons by triggering senescence: new perspective for Rett syndrome. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2012;23(8):1435–1445. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dato S, Crocco P, 'Aquila PD, et al. Exploring the role of genetic variability and lifestyle in oxidative stress response for healthy aging and longevity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;14(8):16443–16472. doi: 10.3390/ijms140816443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liochev SI. Reactive oxygen species and the free radical theory of aging. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2013;60:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]