ABSTRACT

Background and Purpose:

Hamstring injuries are frequent injuries in athletes, with the most common being strains at the musculotendinous junction or within the muscle belly. Conversely, hamstring avulsions are rare and often misdiagnosed leading to delay in appropriate surgical interventions. The purpose of this case report is to describe the history and physical examination findings that led to appropriate diagnostic imaging and the subsequent diagnosis and expedited surgical intervention of a complete avulsion of the hamstring muscle group from the ischium in a military combatives athlete.

Case Description:

The patient was a 25 year‐old male who sustained a hyperflexion injury to his right hip with knee extension while participating in military combatives, presenting with acute posterior thigh and buttock pain. History and physical examination findings from a physical therapy evaluation prompted an urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study, which led to the diagnosis of a complete avulsion of the hamstring muscle group off the ischium.

Outcome:

Expedited surgical intervention occurred within 13 days of the injury potentially limiting comorbidities associated with delayed diagnosis.

Conclusion:

Recognition of the avulsion led to prompt surgical evaluation and intervention. Literature has shown that diagnosis of hamstring avulsions are frequently missed or delayed, which results in a myriad of complications.

Level of Evidence:

Level 4

Keywords: Differential diagnosis, imaging, hamstring avulsion

INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE

Hamstring injuries are a common injury in athletes, frequently occurring in sprinting sports such as track and field,1‐3 soccer,4 and football.5 Most hamstring injuries consist of muscle strains of the long head of the biceps femoris at the musculotendinous junction,6,7 which can be managed with physical therapy.8,9 Complete avulsion of the hamstring muscle group from the ischium is rare10 and requires careful evaluation to be recognized in a time efficient manner, as surgical management may be necessary.11 Hamstring avulsions from the ischium have been reported in skiing sports,10,12,13 judo,14 bull riding,10 running or sprinting, soccer, football, ice hockey, in‐line skating, dancing, tennis, and wrestling.15 The mechanism of injury for a complete avulsion of the hamstring muscle group from the ischium typically occurs with sudden hip flexion with knee extension along with a strong eccentric hamstring contraction.16,17 Hamstring avulsions can be difficult to diagnose acutely due to swelling and patient guarding, which may mask a visibly palpable defect and lead to delays in diagnosis.10,13

Hamstring avulsions do not always require surgical repair but surgical intervention is indicated when a complete avulsion of the hamstring muscle group occurs or when two tendons are involved with retraction greater than two centimeters.17 Beneficial outcomes have been noted for both acute and chronic surgical repair of complete proximal hamstring avulsions when compared to nonoperative management.11 However, acute surgical repair has been documented to provide higher functional scores and strength measures with fewer surgical complications compared to chronic surgical repair at long‐term follow‐ups of a year or more.11,18 The purpose of this case report is to describe the history and physical examination findings that warranted obtaining early diagnostic imaging in order to accurately diagnose and expedite surgical intervention for a complete avulsion of the hamstring muscle group from the ischium in a military combatives athlete.

CASE DESCRIPTION

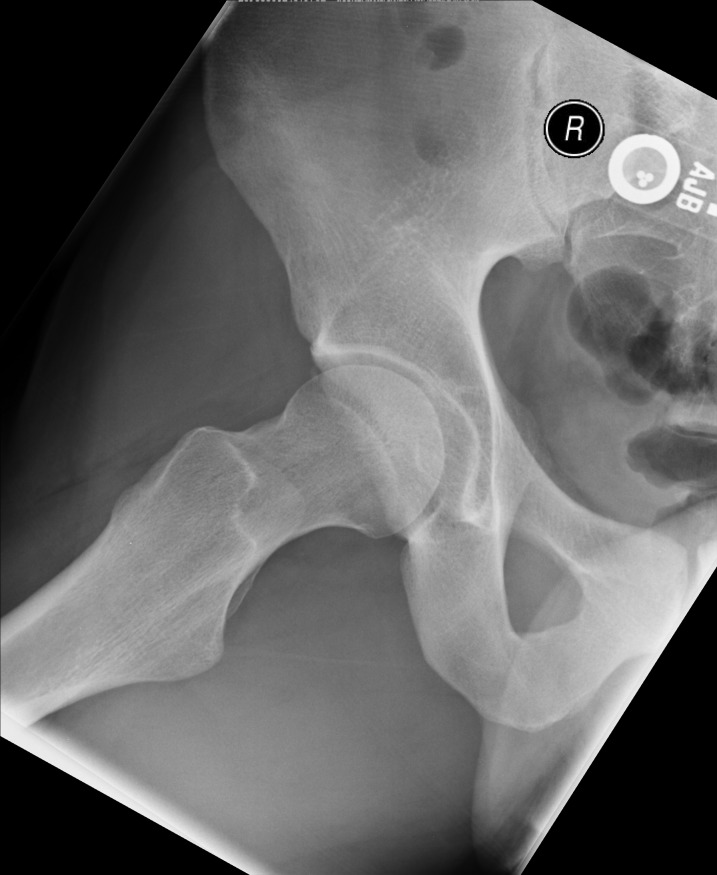

The subject was a 25 year‐old male soldier athlete participating in the “modern army combatives program” (a Brazilian Jiu Jitsu based mixed martial arts program). His primary care physician evaluated him one‐day following his injury and right hip radiographs were ordered (Figures 1 and 2). Radiographs demonstrated no bony abnormalities; the patient was diagnosed with a hamstring muscle strain, placed on work restrictions, and referred to a physical therapist. The patient presented to the physical therapist with a one‐week history of right posterior thigh and buttock pain.

Figure 1.

Anterior to posterior view radiograph of the pelvis and bilateral hips, which was interpreted as normal.

Figure 2.

Frog leg lateral view radiograph of the right hip, which was interpreted as normal.

CLINICAL IMPRESSION

The physical therapist reviewed the patient's radiology report, radiographs, and the primary care provider's documentation on the military electronic medical record system prior to the initial physical therapy evaluation. Prior to meeting the patient the physical therapist's initial working diagnosis was a hamstring strain. However, there are many sports injuries and pathologies that cause posterior hip pain, which should be further explored during the history and physical examination (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis for patients with acute hamstring pain

| Hamstring muscle strain |

| Hamstring muscle avulsion (≤ 2 muscles) |

| Complete hamstring avulsion (3 muscles) |

| Referred pain from the lumbar spine (i.e., lumbar disc pathology) |

| Referred pain from gluteal muscles |

| Sacroiliac dysfunction |

| Hip extensor or rotator muscle strain |

| Adductor muscle strain (adductor magnus) |

| Piriformis syndrome |

| Femoral vein thrombosis |

| Bursitis (i.e., ischiogluteal) |

| Ligament sprain (i.e., sacrotuberous, sacrospinous) |

| Vascular claudication |

| Femoral neck stress fracture |

| Posterior compartment syndrome |

INITIAL PHYSICAL THERAPY EVALUATION

At the initial physical therapy examination, the patient described a rapid hip flexion motion combined with knee extension as the mechanism of injury. He reported feeling a “pop” when his opponent landed on his anterior thigh while he was in a splits position in the sagittal plane (contralateral extremity in hip and knee extension). The patient reported no prior history of hamstring injury and reported a resting pain level of six out of ten on the numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) and eight out of ten when sitting or with any active movement of the hip or knee (all planes of motion). The patient described the quality of pain as sharp, with mid posterior thigh pain that referred proximally into the posterior hip but he denied paresthesia. The patient completed a Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS) to assess his level of function with 80 indicating the highest level of function, while lower numbers indicate lower levels of function.19 The patient's LEFS resulted in a score of 7 out of 80 indicating a very low personal assessment of lower extremity function, and accordingly, he was unable to return to sporting activity.

The patient presented non‐weight bearing on the right lower extremity with axillary crutches, but was able to ambulate during the examination with his knee in full extension. His gait was antalgic when full weight bearing, with a decreased stance phase on the right side using a stiff‐legged gait pattern characterized by decreased knee flexion. With the patient lying prone, visual examination revealed moderate ecchymosis 6 cm distal to the ischial tuberosity with a palpable defect approximately 2.5 cm wide by 5 cm long, 8 cm distal to the ischial tuberosity on the medial aspect of the posterior thigh. Palpation of the posterior medial thigh elicited pain at the site of the defect. Knee flexor strength was assessed with the patient positioned in prone with the knee passively positioned at 90 degrees of flexion. The patient was unable to actively resist manual force and was unable to lower his leg through the full range of motion to the table utilizing an eccentric contraction due to pain and guarding demonstrating a manual muscle testing grade of 2+/5. The proximal hamstring tendon insertion appeared to be absent with palpation during a hamstring contraction.

The patient's reported mechanism of injury, level of function, and clinical exam findings were consistent with a complete hamstring avulsion. Additional key findings that would be associated with a hamstring avulsion included a “pop” at the time of injury, palpable defect,20 swelling,16 ecchymosis,17,20,21 stiff legged gait pattern,17 and an inability to palpate the proximal tendon attachment at the ischial tuberosity.

INTERVENTION

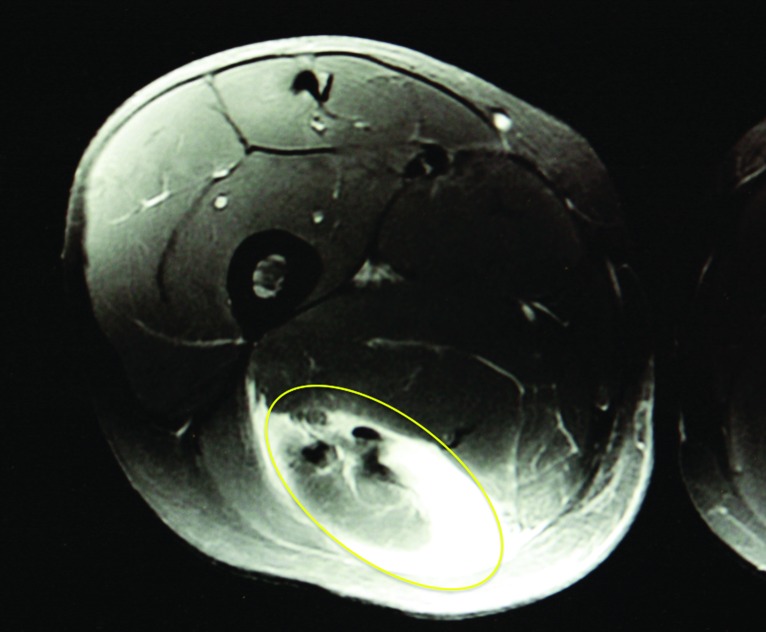

Due to high suspicion of a proximal hamstring avulsion the physical therapist ordered a magnetic resonance image (MRI) study and consulted with a musculoskeletal radiologist to facilitate a same day study. The physical therapist also consulted with the on call orthopaedic physician assistant and an orthopaedic surgeon who agreed to see the patient within two days. MRI (Figures 3‐5) revealed a complete proximal hamstring avulsion off the ischial tuberosity with 5 cm tendon retraction of the semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles and 6.5 cm retraction of the biceps femoris. After evaluation by the orthopedic surgeon, the patient was scheduled for surgical intervention five days later (13 days following his injury).

Figure 3.

Axial proton density fat saturation magnetic resonance image of the right thigh with noted edema (circle) posteriorly.

Figure 5.

Sagittal proton density magnetic resonance image demonstrating a 6.5 cm retraction of the biceps femoris (arrow).

Figure 4.

Coronal STIR magnetic resonance image demonstrating proximal hamstring tendon retraction (arrow).

OUTCOME

Surgical intervention was performed by debriding the ischial tuberosity followed by placement of two helix sutures, which were then woven into the hamstring tendon with one suture serving as a gliding stitch. The tendon was approximated to the ischial tuberosity by the gliding stitch, followed by fixation of the proximal hamstring tendons, restoring the anatomy. One day following surgery, the patient began physical therapy (14 days after initial injury). Post‐operative limitations included: (1) weight‐bearing status starting with toe touch weight‐bearing for 2 weeks, followed by 25% weight‐bearing weeks 2‐4, 50% weight‐bearing weeks 4‐6 with gradual progression to full weight‐bearing and (2) no active hamstring contractions for the first 6 weeks. Bracing and post‐operative rehabilitation was based upon previously publisheded protocols17,22 but will not be covered in this case report, due to its' focus on diagnosis and expedited surgical management. The patient progressed to light jogging three months post‐operatively with no associated pain, until the patient's run progression was halted at approximately four months post‐operative after he sustained an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury on the contralateral lower extremity, unrelated to the hamstring injury. Despite the ACL injury, after 22 months, the patient reported no associated pain or re‐injury of the hamstring.

DISCUSSION

This case report illustrates the clinical evaluation and decision‐making process, including the use of MRI, resulting in expedited surgical intervention for a complete proximal hamstring avulsion. A common mechanism of injury for a proximal hamstring avulsion is combined hip flexion and knee extension.23 Although common with hamstring avulsions, this mechanism of injury is also described in patients with hamstring strains, particularly dancers and those participating in kicking activities.9 Clinical presentation of a hamstring avulsion will typically consist of ecchymosis in the posterior thigh, localized tenderness, and a palpable defect, which can also be consistent with hamstring strains. Additional findings that can assist in differentiating hamstring avulsions from hamstring stains include: proximal tenderness with palpation and an inability to palpate the proximal tendon.

Common patient reported complaints include loss of leg control when walking, painful cramping in the muscle belly, difficulty sitting, and weakness ascending stairs.23 On physical examination, patients with complete hamstring avulsions may have tenderness to palpation of the ischial tuberosity. Birmingham et al15 described an absence of palpable tension in the distal hamstring tendons with the knee actively flexed at 90 degrees while the patient is in a prone position referred to as a positive bowstring sign. A detailed neurological examination is warranted as damage to the sciatic nerve can occur with hamstring retraction.17,21

Diagnostic imaging is essential for confirmation of a suspected proximal hamstring avulsion.17 Radiographs are commonly performed, but typically yield negative results in the adult population due to skeletal maturity.17 Despite the rarity of bony avulsions in a skeletally mature population, they are important to exclude with radiographs. In contrast, it should be noted that adolescents often sustain an apophyseal avulsion, commonly identified on basic radiographs.13

MRI should be used to confirm the diagnosis of a complete hamstring avulsion. Koulouris and Connell24 reported on the accuracy of MRI and sonography on 16 surgically confirmed proximal hamstring avulsions. All 16 patients received MRI, which accurately diagnosed 16 out of the 16 (100%) proximal hamstring avulsions, while sonography was performed on 12 of the patients and accurately identified only 7 out of 12 (58%) demonstrating lower sensitivity.24 Some of the pitfalls of using sonography is the difficulty detecting the injury due to the presence of extensive hematoma combined with the depth of the injured tissue with large gluteal muscles covering the proximal hamstrings.25 Additionally, MRI provides an accurate assessment of the extent of the tendon retraction, if present, as well as tendon morphologic features making it ideal for surgical planning and decision making.25

Nonoperative treatment is indicated in patients with a one tendon avulsion or a two tendon avulsion with a tendon retraction of less than two centimeters.17 Nonoperative management typically consists of rest, ice, modalities, gentle stretching, and gradual return to sport specific training. Patients utilizing nonoperative management should be able to return to sport within six weeks.17

Surgical repair criteria for proximal hamstring avulsions include: (1) involvement of two tendons with greater than two cm of retraction; or (2) three tendon (complete) avulsion regardless of the length of retraction.17 Successful surgical repair has been documented in both acute and chronic injuries;10,11,15,18,26 however, patient outcomes are improved with acute repair within four weeks of injury.15 Harris and colleagues performed a systematic review of 18 studies, reporting that surgical intervention performed within four weeks led to improved patient satisfaction, subjective clinical outcomes, strength and endurance, pain relief, return to prior level of function and reduced re‐rupture rate compared to chronic repairs.11

There is limited evidence on clinical outcomes in chronic repairs of complete distal hamstring avulsions. Cross and colleagues10 reported nine cases of chronic surgical repairs of complete hamstring avulsions with an average of 36 months from injury to surgical repair. All subjects complained of weakness and six complained of inability to run pre‐operatively. At the average 48 month long term follow up, subjects demonstrated 60.2% in hamstring strength and 57.1% in hamstring endurance when compared to the contralateral side with seven subjects returning to their recreational sports.10 In chronic repairs of hamstring avulsions, neurolysis of the sciatic nerve is required due to scar tissue and onset of sciatic nerve symptoms.23 Additional concerns arise with increased time from injury to surgical intervention including: decreased ability to restore anatomy,27 increased postoperative bracing, reduced postoperative outcomes,21 and a more technically challenging surgery.26

CONCLUSION

In summary, proximal hamstring avulsions are often delayed or misdiagnosed. As medical professionals working with athletes, it is important to understand the clinical presentation of hamstring avulsions and the use of, or referral for, appropriate diagnostic imaging. Despite successful surgical outcomes in both acute and chronic cases, expedited surgical care occurring within four weeks leads to improved patient satisfaction and pain relief while mitigating complications in surgery and decreasing the probability of sciatic nerve involvement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennell KL Crossley K Musculoskeletal injuries in track and field: incidence, distribution and risk factors. Aust J Sci Med Sport. Sep 1996;28(3):69‐75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malliaropoulos N Isinkaye T Tsitas K Maffulli N Reinjury after acute posterior thigh muscle injuries in elite track and field athletes. Am J Sports Med. Feb 2011;39(2):304‐310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malliaropoulos N Mendiguchia J Pehlivanidis H, et al. Hamstring exercises for track and field athletes: injury and exercise biomechanics, and possible implications for exercise selection and primary prevention. Br J Sports Med. Sep 2012;46(12):846‐851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson G Barnes CA Portas MD Factors associated with increased propensity for hamstring injury in English Premier League soccer players. J Sci Med Sport. Jul 2010;13(4):397‐402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elliott MC Zarins B Powell JW Kenyon CD Hamstring muscle strains in professional football players: a 10‐year review. Am J Sports Med. Apr 2011;39(4):843‐850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connell DA Schneider‐Kolsky ME Hoving JL, et al. Longitudinal study comparing sonographic and MRI assessments of acute and healing hamstring injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol. Oct 2004;183(4):975‐984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slavotinek JP Verrall GM Fon GT Hamstring injury in athletes: using MR imaging measurements to compare extent of muscle injury with amount of time lost from competition. AJR Am J Roentgenol. Dec 2002;179(6):1621‐1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherry MA Best TM A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. Mar 2004;34(3):116‐125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heiderscheit BC Sherry MA Silder A Chumanov ES Thelen DG Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. Feb 2010;40(2):67‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross MJ Vandersluis R Wood D Banff M Surgical repair of chronic complete hamstring tendon rupture in the adult patient. Am J Sports Med. Nov‐Dec 1998;26(6):785‐788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris JD Griesser MJ Best TM Ellis TJ Treatment of proximal hamstring ruptures ‐ a systematic review. Int J Sports Med. Jul 2011;32(7):490‐495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blasier RB Morawa LG Complete rupture of the hamstring origin from a water skiing injury. Am J Sports Med. Jul‐Aug 1990;18(4):435‐437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarimo J Lempainen L Mattila K Orava S Complete proximal hamstring avulsions: a series of 41 patients with operative treatment. Am J Sports Med. Jun 2008;36(6):1110‐1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurosawa H Nakasita K Nakasita H Sasaki S Takeda S Complete avulsion of the hamstring tendons from the ischial tuberosity. A report of two cases sustained in judo. Br J Sports Med. Mar 1996;30(1):72‐74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birmingham P Muller M Wickiewicz T Cavanaugh J Rodeo S Warren R Functional outcome after repair of proximal hamstring avulsions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Oct 5 2011;93(19):1819‐1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orava S Kujala UM Rupture of the ischial origin of the hamstring muscles. Am J Sports Med. Nov‐Dec 1995;23(6):702‐705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen S Bradley J Acute proximal hamstring rupture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. Jun 2007;15(6):350‐355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen SB Rangavajjula A Vyas D Bradley JP Functional results and outcomes after repair of proximal hamstring avulsions. Am J Sports Med. Sep 2012;40(9):2092‐2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binkley JM Stratford PW Lott SA Riddle DL The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network. Phys Ther. Apr 1999;79(4):371‐383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakravarthy J Ramisetty N Pimpalnerkar A Mohtadi N Surgical repair of complete proximal hamstring tendon ruptures in water skiers and bull riders: a report of four cases and review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. Aug 2005;39(8):569‐572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carmichael J Packham I Trikha SP Wood DG Avulsion of the proximal hamstring origin. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Oct 1 2009;91 Suppl 2:249‐256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali K Leland JM Hamstring strains and tears in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. Apr 2012;31(2):263‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sallay PI Ballard G Hamersly S Schrader M Subjective and functional outcomes following surgical repair of complete ruptures of the proximal hamstring complex. Orthopedics. Nov 2008;31(11):1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koulouris G Connell D Evaluation of the hamstring muscle complex following acute injury. Skeletal Radiol. Oct 2003;32(10):582‐589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koulouris G Connell D Hamstring muscle complex: an imaging review. Radiographics. May‐Jun 2005;25(3):571‐586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood DG Packham I Trikha SP Linklater J Avulsion of the proximal hamstring origin. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Nov 2008;90(11):2365‐2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klingele KE Sallay PI Surgical repair of complete proximal hamstring tendon rupture. Am J Sports Med. Sep‐Oct 2002;30(5):742‐747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]