Summary

Background

Our objective was to examine the longitudinal trends of substance use (cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use) in a cohort of young people by participants’ eventual educational attainment. We aimed to pinpoint the life stages when the socioeconomic disparities in these behaviors emerge.

Methods

The analytic sample included 1,902 participants from Project EAT, a 10-year longitudinal study. Participants were assessed from early adolescence (middle school) through middle young adulthood (mid 20s) and categorized into groups of eventual educational attainment.

Results

Generally, for cigarettes and marijuana, disparities were evident by early adolescence with prevalence of use highest among those who had no secondary education, followed by 2-year college and then 4-year college attendees/graduates. With alcohol, reported use tended to be similar during adolescence for all three education groups, but then diverged during young adulthood. At this stage the 4-year college group reported the most weekly alcohol use, but the no postsecondary education group reported the most daily use.

Conclusions

The points at which disparities in substance use behaviors first emerge and later escalate can offer guidance as to how to craft, and when to target, interventions and policies.

Keywords: smoking, alcohol, marijuana, young adulthood, adolescence, socio-economic status

Introduction

Adult socioeconomic position (SEP) is a marker for both health (1,2) and health-related behaviors such as smoking (3), alcohol use (4), and other substance use; in most instances, less healthful behaviors are more prevalent among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. However, the developmental processes that result in adult health behavior patterns are set into motion long before maturity. Meanwhile, eventual socioeconomic position is reliant on the critical period of social and educational sorting that occurs during late adolescence and young adulthood when a young person may or may not continue onto college, enter the labor market, commit to a romantic partner, and/or begin family life. By the time a person moves from young to middle adulthood, typically both health behaviors and socioeconomic position have crystallized. The development of health behaviors and the simultaneous journey toward a particular socioeconomic path is likely a dynamic process where the early manifestations of what will become one’s eventual educational attainment, an important determinant of SEP, influence health behaviors and vice versa. Understanding the timeline of this process and when differential health behavior patterns emerge is crucial to eliminating the vast socioeconomic disparities seen in smoking, problem alcohol use, and other substance use. An understanding of when and how disparities emerge for various groups can inform effective strategies that prevent health inequities.

Tobacco, alcohol, and substance use prevalence varies greatly among young adults by educational attainment. The smoking prevalence among young adults who are enrolled in college or have a college degree is less than half that of young adults who are not in college and do not have a college degree (5–8). Furthermore, the type of postsecondary education is also an important predictor of tobacco use with several studies showing that 2-year college students are far more likely to be smokers compared to their peers who attend 4-year college (9–12). Conversely, in the case of alcohol, young adults who are enrolled in college display risky alcohol-related behaviors as frequently or even more frequently than those who are not enrolled in college (13–16). With binge drinking, 4-year college students appear to be more likely to report this behavior compared to 2-year college students (12,17). There is some inconsistency in the literature on use of illicit drugs (perhaps because the various drugs have different use patterns), with one study reporting lower use in young adults enrolled in college (14) and another, which measured socioeconomic position by a young adult’s parents’ education, found that marijuana and cocaine use were more common among young adults at higher socioeconomic positions (18).

Several authors have taken the approach of viewing socioeconomic position as an outcome and examined whether substance use in adolescence predicts lower educational attainment and SEP. Tucker and colleagues found that those who were in trajectories that were categorized by abstaining from cigarettes, only trying cigarettes, or decreasing cigarettes were more likely to graduate from college (19). Similarly, it has been demonstrated that a trajectory of high use of marijuana that begins early, by age 13, is associated with poorer socioeconomic position in young adulthood (20). In one study, marijuana use in high school was been associated with future dropout but about half of this association could be explained by factors that occurred prior to a youth’s first experience with marijuana, and the association disappeared after adjustment for cigarette smoking (21). One plausible explanation why the association disappeared when smoking was added to the models is that there are underlying, pre-existing factors that predispose young people to both marijuana and smoking and lead to dropout.

Despite the importance of family influences on these substance use behaviors, family SEP appears to be less relevant than an individual’s own socioeconomic path through young adulthood. Research in the US has shown that low parental SEP predicts membership in heavier smoking trajectories from ages 10 to 25 years and high parent socioeconomic position predicts membership in non-smoking trajectories (22). However, in a nationally representative cohort of US adolescents (National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health), Yang and colleagues found that family SEP was minimally associated with smoking in adolescence and not clearly associated with smoking in early adulthood; in contrast, young adults’ own socioeconomic position was the important contributor to smoking (23). In this study, family influences, which are likely correlated with family SEP, such as whether there was a smoker in the home and whether there was easy access to cigarettes, were the relevant family factors (23), which is similar to what has been observed in previous research (24). Internationally, studies have shown that family socioeconomic position has little influence on smoking behavior during adolescence and young adulthood compared to the current, adult SEP of the young person themselves (25–27). With alcohol, parental SEP had a limited relationship to the number of episodes of early adolescent (age 11–15) drunkenness in a 28 country (Europe and North America) study (28).

Given the previous research suggesting an intertwined development of substance use behaviors and educational attainment trajectory, and a need to better understand the origins of health behavior disparities for intervention development, we sought to examine patterns of substance use by eventual educational attainment. Using data gathered for Projects EAT, EAT II, and EAT III, we examined the longitudinal trends of substance use (smoking, alcohol use and marijuana use) in a cohort of young people beginning in early adolescence (middle school age) through the middle young adult (mid 20s) periods of the lifespan. We compared three socio-economic groups: 1) young adults who were not enrolled in, or graduates of, postsecondary education; 2) young adults enrolled in, or graduates of, 2-year postsecondary institutions; and 3) young adults enrolled in, or graduates of, 4-year postsecondary institutions. We hypothesized that these groups would have distinct developmental patterns for each substance use outcome (smoking, alcohol use, and marijuana use) and that these disparities would emerge long before the postsecondary educational period.

Methods

Study Design and Population

For this analysis we used data from Project EAT (Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults)-I, II, and III, a 10-year longitudinal study with three study waves (29). The analytic sample includes 1,902 young adults who responded at all three time points. At baseline, (Time 1) junior and senior high school students at 31 public schools in the Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area of Minnesota completed surveys and anthropometric measures during the 1998–1999 academic year (30). Participants were also contacted five (Time 2) and 10 (Time 3) years later (in 2003–2004 and 2008–2009 respectively). All procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Minnesota institutional review board.

Of the original 4,746 participants, 1,304 (27.5%) were lost to follow-up for various reasons, primarily missing contact information at Time 1 (n=411) and no address found at follow-up (n=712). For Project EAT-III, survey invitation letters, providing the web address and a unique password for completing the online version of the Project EAT-III survey and a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) were mailed to the remaining 3,442 participants. After excluding surveys that were determined to be invalid and/or incomplete, the final sample included a total of 2,287 young adults, representing 66.4% of participants who could be contacted (48.2% of the original school-based sample). Of these, the 1,902 who responded to both prior surveys were included in our analytic sample. One third of sample (30.3%) were from the younger cohort – at Time 1 they were in “early adolescence” developmental stage (mean age = 12.8±0.7 years) and at Time 3 they were in “early young adulthood” (mean age = 23.2±1.1 years). The rest (69.7%) were in the older cohort – at Time 1 they were in “middle adolescence” developmental stage (mean age = 15.9±0.8 years) and at Time 3 they were in “middle young adulthood” (mean age = 26.2±0.8 years). Thus, in this study we are able to capture four developmental periods of adolescence (early and middle) and young adulthood (early and middle).

Measures

Substance use was measured with three items: “How often have you used the following [cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana] during the past year (12 months)?” The five response choices for each substance were: “never,” “a few times,” “monthly,” “weekly,” and “daily.” Test-retest reliability was assessed in a diverse adolescent sample at EAT-I (n=161) and examined in a sample of 66 young adults at EAT-III and for these three substance use items ranged from 77–81%. Each substance was dichotomized into at least monthly use vs. less frequent (or nonuse). For alcohol we also dichotomized into at least weekly use vs. less frequent and daily use vs. less frequent (or nonuse) because we thought daily use would be very rare for the youth at early adolescence, but weekly use at that age can be seen as a risky behavior.

Eventual educational attainment was determined by the responses to two items. The first item “Which of the following describes your student status over the past 12 months?” (test-retest agreement = 95%) had the following response options, “not a student,” “part-time student at a community or technical college,” “full-time student at a community or technical college,” “part-time student at a 4-year college,” and “full-time student at a 4-year college.” The second item, “What is the highest level of education that you have completed?” (test-retest agreement = 97%) gave participants six response options, “middle school or junior high,” “some high school,” “high school graduate or GED,” “some college,” “technical school degree,” “college graduate.” We made three educational categories: 1) did not attend or graduate from any type of college (“no postsecondary”), 2) did not attend or graduate from a 4-year college but attended or graduated from a community or technical college (“2-year college”), and 3) attended or graduated from a 4-year college (“college”).

Analysis

Because attrition from the Time 1 sample did not occur at random, in all analyses, the data were weighted using the response propensity method (31). Response propensities (i.e., the probability of responding to the Project EAT-III survey) were estimated using a logistic regression of response at Time 3 on a large number of predictor variables from the Project EAT-I survey. Weights were additionally calibrated so that the weighted total sample sizes used in analyses for each gender cohort accurately reflect the actual observed sample sizes in those groups. The weighting method resulted in estimates representative of the demographic make-up of the original school-based sample, thereby allowing results to be more fully generalizable to the population of young people in the Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area. Specifically, the weighted sample was 48.3% white, 18.5% African American, 19.7% Asian, 5.5% Hispanic, 3.5% Native American, and 4.5% mixed or other race/ethnicity.

We used generalized estimating equation (GEE) models to estimate the proportion of individuals that used cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana, at the early adolescence, middle adolescence, early young adult, and middle young adult developmental periods and tested differences among these across eventual educational attainment. The longitudinal dichotomous measurements were collected at three time points for each individual across two different age cohorts (starting in 1998, the younger cohort was in early adolescence, the older cohort was in middle adolescence). GEE accounts for the tracking of behaviors within individuals, which otherwise could lead to variance inflation and incorrect confidence intervals. An independent working correlation matrix and robust standard errors were used in all analyses.

All models included a time-varying categorical indicator for developmental period and further controlled for age in years (centered at the mean age of the developmental period) to account for minor variability in age range within developmental period. A categorical indicator of eventual educational attainment and its interaction with developmental period were included in the model to test for differences in trajectories of substance use between different educational attainment groups. Initial models tested for differential cohort effects by including a cohort by educational attainment, cohort by developmental group, and a three way interaction of cohort by education by developmental group. These interactions were not significant for any substance use outcome and thus were not included in final models implying results are pooled across cohorts, specifically in the high school and early young adult developmental age groups where the cohorts overlapped.

Estimates for developmental trajectories by educational attainment by gender we obtained by additionally including an interaction between gender and educational attainment, and a three way interaction between gender, educational attainment and developmental period. For some substance outcomes, the three-way interaction was significant indicating differential trajectories by educational attainment by gender and so we also describe these results by gender.

Results

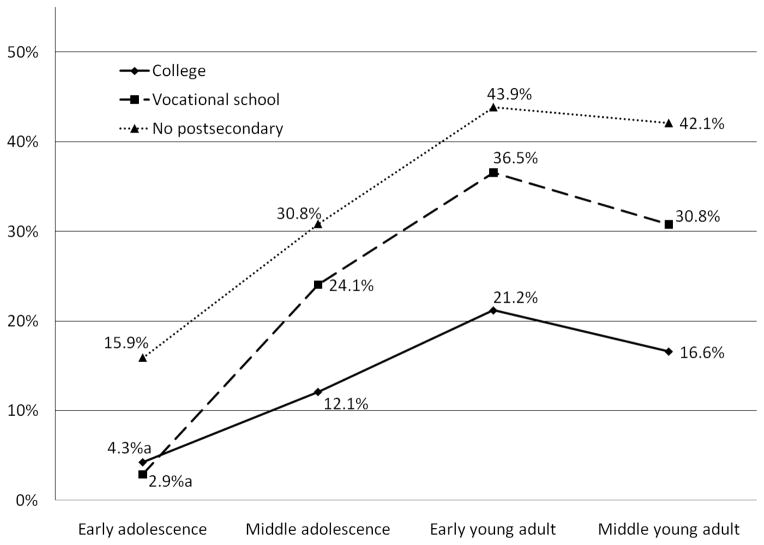

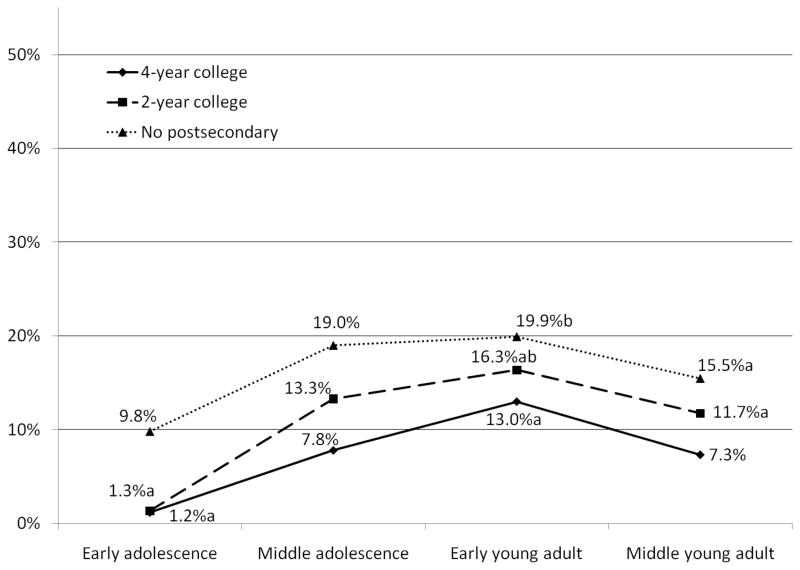

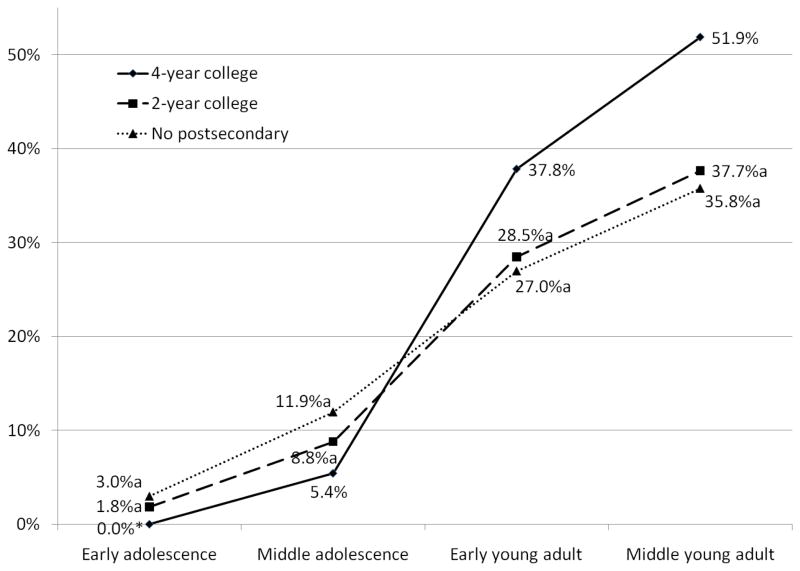

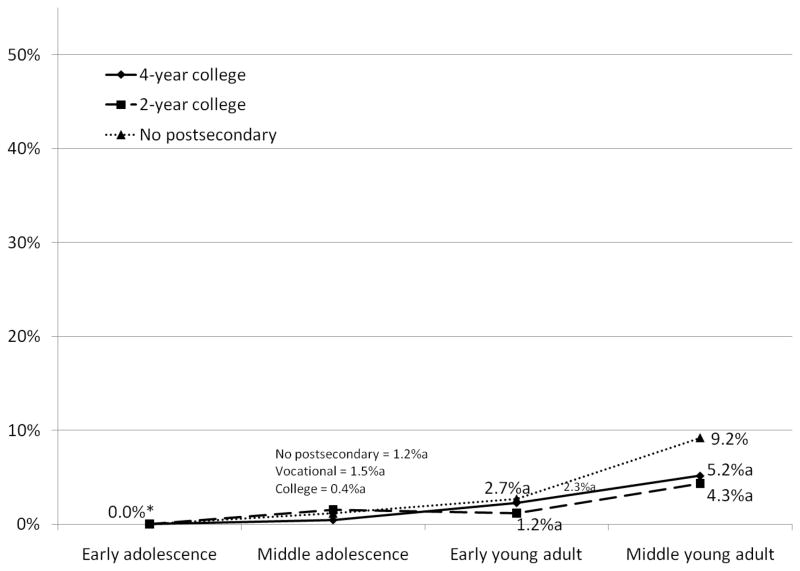

Generally speaking, for monthly cigarette (Figure 1)1 and marijuana use (Figure 2), the prevalence increased for each group until early young adulthood, when it levels or declines, and was highest among those who had no secondary education, followed by 2-year college students and then 4-year college students, with few exceptions. The prevalence of weekly (Figure 3) and daily (Figure 4) alcohol use starts very low in early adolescence and steadily increases through middle young adulthood for all educational groups. For weekly alcohol intake, the 2-year college and no postsecondary educational trends were not significantly different from each other at any developmental stage. For daily alcohol use, only in middle young adulthood did differences emerge where those with no postsecondary education were more likely to drink daily compared to those in the 4-year college group (p = 0.045) and 2-year college group (p = 0.042). No differences could be tested for daily alcohol use in at the early adolescence age since rates were so small.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of monthly cigarette smoking by eventual educational attainment group, adjusted for age and gender. At each developmental stage, percentages that do not share a letter after the % are significantly different from each other.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of monthly marijuana use by eventual educational attainment group, adjusted for age and gender. At each developmental stage, percentages that do not share a letter after the % are significantly different from each other.

Figure 3. Prevalence of weekly alcohol use by eventual educational attainment group, adjusted for age and gender. At each developmental stage, percentages that do not share a letter after the % are significantly different from each other.

*Indicates that a statistical test comparing this group to the others could not be done due to zero youth in this group reporting use.

Figure 4. Prevalence of daily alcohol use by eventual educational attainment group, adjusted for age and gender. At each developmental stage, percentages do not share a letter after the % are significantly different from each other.

*Indicates that a statistical test could not be done due to zero youth in this group reporting use.

Due to the evidence of differential trends by gender for cigarettes and marijuana (gender interactions: cigarettes, p = 0.009; marijuana, p = 0.002), we also examined these use trends for stratified by gender (data not shown in figures). For cigarettes, among males, those who went on to 4-year colleges reported the lowest use, followed by the 2-year college group, and finally the no postsecondary group had the highest cigarette use at all developmental stages. Meanwhile, among females, by middle adolescence and beyond, the 2-year college and no postsecondary groups had similar use prevalences and were significantly more likely to smoke than their peers who had gone or would go to a 4-year college. With marijuana use starting in high school, among males in the 2-year college group had a similar pattern of use to those males who would attend 4-year college. Conversely, among females, the 2-year college group was more like those who would not go on to postsecondary education.

Discussion

In this study we found that beginning in early adolescence and moving through middle young adulthood, patterns in the prevalence of smoking, alcohol use, and marijuana use differ substantially by eventual educational attainment. With smoking and marijuana, disparities begin early. Cigarette and marijuana use was reported by approximately 10–15% of those who would not go on to postsecondary education in early adolescence; throughout the developmental course this group reported higher use than the 2-year college group which in turn reports higher use than the 4-year college group for these substances. As the youth matured, alcohol use increased at every successive developmental stage and did not level off even by the end of the 10-year observational period. All three groups basically reported similar alcohol use in adolescence, but disparities emerged in young adulthood. By young adulthood, the 4-year college group reported the highest prevalence of weekly alcohol use, while the no postsecondary education group reported the highest prevalence of daily use. Hence, the disparities in substance use are apparent in different times for each substance, emerging by early adolescence for cigarette and marijuana use, but not until young adulthood for daily alcohol use.

In this paper we modeled whether a future event, eventual educational attainment, influenced substance use prevalence and the trajectories of use which start long before the advent of a postsecondary course of education. How could it be possible that something in the future, such as whether an adolescent attends college, could affect past substance use behavior? One possibility is a “reverse causality” situation where the considered outcome is actually in some way causing the predictor because early (and not readily apparent) manifestations of the “outcome,” such as diminished educational aspirations or peer associations, are already working to sort individuals into lower educational attainment groups. In this case, the “outcome,” eventual educational attainment, would be actually driving the “predictor.” We do know that lower educational aspirations in early adolescence are associated with beginning to smoke earlier, smoking through young adulthood (32), and being a regular marijuana user from adolescence through young adulthood (33,34). Additionally, peer effects appear to be very important on the uptake of smoking in middle adolescence and early adulthood (35,36). The seeds of educational trajectory and substance use are likely interwoven and mutually reinforcing. In this case, it might not be very useful to try to tease out the temporality of this relationship. Instead, the identification of youth who are moving in these patterns that are less advantageous for their health and wellbeing is the more public-health relevant point. A second possibility is that substance use in adolescence leads to educational attainment in a more straightforward way such as interfering with a young person’s cognitive capacity to do academic work. Several researchers have examined this type of model, looking at substance use as a predictor and education or socioeconomic position as an outcome and found that substance use was associated with lower SEP longitudinally (19–21).

Policy may be an especially effective way of reaching young people who are in a lower socioeconomic position in society. It can be difficult for something like a health education intervention to reach young people who do not continue in postsecondary education because they are not affiliated with an educational institution and in general, younger adults are less likely to have health insurance or a consistent health care provider (37,38). In one study, stronger state-level tobacco policy (e.g. age-of-sale enforcement policies, penalties, etc.) was associated with smoking trajectories of low-income females during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood more so than other SEP groups (36). Policy can be especially powerful for groups that have limited resources to change their own environment (such as an employment in an establishment that allows indoor smoking).

The strengths of this study are the diverse population-based sample, large numbers of 2-year and no postsecondary education-bound youth, and long follow-up window. A limitation of our study is the potential for misclassification of participants’ eventual educational attainment. Since our participants were only followed into their mid-20s, it is possible that some have gone or will go on to attain more education than we have recorded. Although the typical age of graduating with a bachelor’s degree in the US is between age 22–24 (39), we know that some individuals will not have graduated at the time of their last survey. Thus, we included not just people who have graduated from two- and four- year colleges, but also those who reported currently attending such an institution when they were surveyed. However, this solution introduces the potential for misclassification in the other direction as not all participants who are currently attending an educational program will complete it and thus be able to graduate to the socioeconomic position that the degree would confer. In the future, research should continue to follow these young adults and examine how substance use patterns continue to change over the course of the later stages of adulthood while tracking whether individuals finish their education or attain more. This would help clarify what the implications of these early trajectories might be across the lifespan. Additionally, future cohort studies on adolescent health should ask young adolescents about their educational plans as this may predict various outcomes.

In order to address educational disparities in substance use behavior, it is important to understand the natural history of these inequalities. The points at which disparities first emerge and later escalate can offer guidance as to how to craft and target interventions and policies. Examining the prevalence of substance use for these three groups side-by-side shows points where the groups diverge and disparities begin and thus when and with whom to intervene upon. If indeed substance use and educational attainment are closely linked, intervening on substance use may also positively influence educational aspirations, which would have many benefits for the future wellbeing of young people.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant Number R01HL084064 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (PI: Dianne Neumark-Sztainer). Additional salary support for Dr. Widome was provided by a VA Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award CDA 09-012-2 and National Cancer Institute Award K07CA126837 for Dr. Laska. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States government.

Footnotes

The figures show trends in substance use by educational group, pooled across gender. In all figures, percentages that do not share a letter are significantly different (p < 0.05) from each other at that particular developmental stage. For instance, for monthly cigarette use among early adolescents (Figure 1), the prevalence estimate for the 4-year college group (4.3%) was significantly different from both the 2-year college (2.9%) and no postsecondary education (15.9%) group. The 2-year and no postsecondary education groups are not statistically different from each other and thus share the letter “a” after their estimates on the figure.

References

- 1.Kestilä L, Martelin T, Rahkonen O, Härkänen T, Koskinen S. The contribution of childhood circumstances, current circumstances and health behaviour to educational health differences in early adulthood. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:164. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan GA, Baltrus PT, Raghunathan TE. The shape of health to come: prospective study of the determinants of 30-year health trajectories in the Alameda County Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Jun;36(3):542–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O, Karvonen S, Lahelma E. Socioeconomic status and smoking: analysing inequalities with multiple indicators. Eur J Public Health. 2005 Jun;15(3):262–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casswell S, Pledger M, Hooper R. Socioeconomic status and drinking patterns in young adults. Addiction. 2003 May;98(5):601–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence D, Fagan P, Backinger CL, Gibson JT, Hartman A. Cigarette smoking patterns among young adults aged 18–24 years in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(6):687–97. doi: 10.1080/14622200701365319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green MP, McCausland KL, Xiao H, Duke JC, Vallone DM, Healton CG. A Closer Look at Smoking Among Young Adults: Where Tobacco Control Should Focus Its Attention. Am J Public Health [Internet] 2007 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.103945. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17600242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2003. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steele JR, Raymond RL, Ness KK, Alvi S, Kearney I. A comparative study of sociocultural factors and young adults’ smoking in two Midwestern communities. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9( Suppl 1):S73–82. doi: 10.1080/14622200601083541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg CJ, An LC, Thomas JL, Lust KA, Sanem JR, Swan DW, et al. Smoking patterns, attitudes and motives: unique characteristics among 2-year versus 4-year college students. Health Educ Res [Internet] 2011 Mar 29; doi: 10.1093/her/cyr017. [cited 2011 Jun 8]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21447751. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sanem JR, Berg CJ, An LC, Kirch MA, Lust KA. Differences in tobacco use among two-year and four-year college students in Minnesota. J Am Coll Health. 2009 Oct;58(2):151–9. doi: 10.1080/07448480903221376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Boyle R, McCarty MC, Thoele MJ. Toward a Better Understanding of Smoking Cessation Among Young Adults. Am J Public Health [Internet] 2007 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098491. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17600256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.VanKim NA, Laska MN, Ehlinger E, Lust K, Story M. Understanding young adult physical activity, alcohol and tobacco use in community colleges and 4-year post-secondary institutions: A cross-sectional analysis of epidemiological surveillance data. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:208. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slutske WS. Alcohol use disorders among US college students and their non-college-attending peers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(3):321–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gfroerer JC, Greenblatt JC, Wright DA. Substance use in the US college-age population: differences according to educational status and living arrangement. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(1):62–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paschall MJ, Flewelling RL. Postsecondary education and heavy drinking by young adults: the moderating effect of race. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(4):447–55. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crosnoe R, Riegle-Crumb C. A life course model of education and alcohol use. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(3):267–82. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Velazquez CE, Pasch KE, Laska MN, Lust KA, Story M, Ehlinger E. Differential prevalence of alcohol use among 2- and 4-year college students. Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humensky JL. Are adolescents with high socioeconomic status more likely to engage in alcohol and illicit drug use in early adulthood? Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2010;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Klein DJ. Cigarette smoking from adolescence to young adulthood: women’s developmental trajectories and associates outcomes. Womens Health Issues. 2006 Feb;16(1):30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellickson PL, Martino SC, Collins RL. Marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: multiple developmental trajectories and their associated outcomes. Health Psychol. 2004 May;23(3):299–307. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCaffrey DF, Pacula RL, Han B, Ellickson P. Marijuana use and high school dropout: the influence of unobservables. Health Econ. 2010 Nov;19(11):1281–99. doi: 10.1002/hec.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White HR, Nagin D, Replogle E, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Racial differences in trajectories of cigarette use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004 Dec 7;76(3):219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang S, Lynch J, Schulenberg J, Roux AV, Raghunathan T. Emergence of socioeconomic inequalities in smoking and overweight and obesity in early adulthood: the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. American journal of public health. 2008;98(3):468–77. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melchior M, Chastang J-F, Mackinnon D, Galéra C, Fombonne E. The intergenerational transmission of tobacco smoking--the role of parents’ long-term smoking trajectories. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010 Mar 1;107(2–3):257–60. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glendinning A, Shucksmith J, Hendry L. Social class and adolescent smoking behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 1994 May;38(10):1449–60. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paavola M, Vartiainen E, Haukkala A. Smoking from adolescence to adulthood: the effects of parental and own socioeconomic status. Eur J Public Health. 2004 Dec;14(4):417–21. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karvonen S, Rimpelä AH, Rimpelä MK. Social mobility and health related behaviours in young people. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999 Apr;53(4):211–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.4.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richter M, Leppin A, Nic Gabhainn S. The relationship between parental socio-economic status and episodes of drunkenness among adolescents: findings from a cross-national survey. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:289. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan P, Moe J. Overweight status and eating patterns among adolescents: Where do youth stand in comparison to the Healthy People 2010 Objectives? Am J Pub Health. 2002;92(5):844–51. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neumark-Sztainer D, Croll J, Story M, Hannan PJ, French SA, Perry C. Ethnic/racial differences in weight-related concerns and behaviors among adolescent girls and boys: findings from Project EAT. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(5):963–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little RJA. Survey nonresponse adjustments for estimates of means. International Statistical Review. 1986;54(2):137–9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Whiteman M, Cohen P, Finch SJ. Developmental trajectories of cigarette smoking from adolescence to the early thirties: personality and behavioral risk factors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008 Aug;10(8):1283–91. doi: 10.1080/14622200802238993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brook JS, Zhang C, Brook DW. Developmental Trajectories of Marijuana Use from Adolescence to Adulthood: Personal Predictors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011 Jan;165(1):55–60. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brook JS, Adams RE, Balka EB, Johnson E. Early adolescent marijuana use: risks for the transition to young adulthood. Psychol Med. 2002 Jan;32(1):79–91. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West P, Sweeting H, Ecob R. Family and friends’ influences on the uptake of regular smoking from mid-adolescence to early adulthood. Addiction. 1999 Sep;94(9):1397–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.949139711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim H, Clark PI. Cigarette smoking transition in females of low socioeconomic status: impact of state, school, and individual factors. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60( Suppl 2):13–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.045658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams PF, Martinez ME, Vickerie JL. Summary health statistics for the U.S. population: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Vital Health Stat. 2010 Dec;10(248):1–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pleis J, Ward B, Lucas J. Summary health statistics for the U.S. population: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Vital Health Stat. 2010 Dec;10(249):1–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Digest of Education Statistics. 2010 [Internet]. [cited 2011 Jul 19]. Available from: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d10/tables/dt10_422.asp.