INTRODUCTION

Virtually all US jurisdictions have criminal measures that can be imposed in cases of knowing exposure to HIV. Although some states rely on traditional criminal provisions such as reckless endangerment, the majority of US states have enacted HIV-specific statutes. These statutes include those criminalizing sexual exposure, sharing contaminated injection equipment, or donating blood or tissue. Many states also have statutes that enhance sentences for crimes such as sexual assault or prostitution when committed by someone who knows that he or she has HIV. Tennessee has both types of provisions (1,2).

Although there have been reports of prosecutions of defendants for HIV exposure or transmission since early in the HIV epidemic (3,4), relatively little is known about how these laws are actually enforced. Federal law does not require jurisdictions to report violations of these statutes as they do for homicide and other specific crimes. If there is any record of statutory activity at all, it often includes convictions, not arrests. Yet convictions may greatly under-represent the number of times a statute is invoked--especially in a system such as we have in the US where overcharging is common and verdicts are often reached by plea bargain. Because reporting systems vary greatly between jurisdictions and because the quality of records or their comprehensiveness can vary even within a jurisdiction, tracking cases can be very difficult.

Due to this lack of comprehensive data, previous studies of prosecutions had to rely on published court reports and the news media to identify cases (3,4). Consequently, these studies were based on incomplete data and there was no simple way to determine how many other arrests, prosecutions, or convictions had taken place. This lack of data has resulted in obvious but important questions going unanswered, including: how frequently these laws are enforced; how the police decide whom to arrest and what motivates them to act; how prosecutors decide whom to charge and when to allow defendants to plea to a lesser charge; whether characteristics of defendants make them more likely to be charged with HIV-specific offenses; whether characteristics of the complaining witness matter; what proportion of arrests lead to convictions; and whether persons convicted of HIV-specific crimes get harsher sentences than those convicted of other offenses.

This paper provides a step towards greater understanding of the enforcement of HIV exposure laws in the US by examining comprehensive data on all those charged with HIV exposure and aggravated prostitution (i.e., solicitation by one who knows he or she has HIV infection) within a single jurisdiction, the Nashville, Tennessee prosecutorial region, over an 11-year period. The paper reports descriptive statistics of those charged, presents information related to the circumstances of the HIV-related charges, and discusses what these data can and cannot tell us.

The Laws

Tennessee makes it a Class C felony for a person who knows he or she has HIV to engage in “intimate contact” with another person (1). Intimate contact is broadly defined as “the exposure of the body of one person to a bodily fluid of another person in any manner that presents a significant risk of HIV transmission.” The law does not define the phrase “significant risk,” making it difficult to know which sexual activities are proscribed and under what conditions. For example, Tennessee's statute is silent on condom use. It is not clear if an individual who engages solely in condom-protected sex could be charged with violating Tennessee's statute. The answer to this could depend on whether prosecutors and courts believe that condom-protected intercourse poses a “significant risk” of transmission as the statute requires. Penalties for violating Tennessee's HIV exposure law include imprisonment for 3 to 15 years and fines up to $10,000 (5).

In order for an HIV-positive person in Tennessee to engage lawfully in intimate contact with another person, the HIV-positive person must disclose his or her positive serostatus to the partner and receive their consent in advance of the activity (1). If charged with violating the HIV exposure statute, the HIV-positive person must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the partner knew the defendant was infected with HIV, knew that the contact could result in infection with HIV, and gave advance consent to the action with that knowledge. HIV transmission is not required for conviction. The law also criminalizes such activities as donating blood or tissue or transferring contaminated “intravenous or intramuscular drug paraphernalia.” The statute was amended in 2011 to include persons who are infected with Hepatitis B and C viruses, although the penalty for exposure in these cases remains a misdemeanor.

Tennessee also has an aggravated prostitution statute that makes it a crime when a person, knowing he or she is infected with HIV, “engages in sexual activity as a business or is an inmate in a house of prostitution or loiters in a public place for the purpose of being hired to engage in sexual activity” (2). Exposure to HIV is not required for prosecution, nor is sexual or even physical contact. Aggravated prostitution is a Class C felony carrying the same penalties as the HIV exposure law, 3-15 years imprisonment and up to $10,000 fine (5). The same activities, solicitation of sex for money, by a person not diagnosed with HIV, is a either a Class B or a Class A misdemeanor. Ordinary solicitation is a Class B misdemeanor, with penalties of up to six months incarceration and no more than $500 fine (5), while solicitation within 100 feet of a church or one-and-a-half miles of a school is a Class A misdemeanor, with penalties up to 11 months 29 days incarceration and fines of $1000 to $2500 (6).

Neither Tennessee's HIV exposure nor aggravated prostitution laws require that the defendant intend to infect or even to harm the other person. The “intent” element of the laws is satisfied when an individual engages in the prohibited behaviors while knowing he or she has HIV infection. The laws do not require actual transmission, or, in the case of aggravated prostitution, actual physical contact.

Currently, persons convicted of violating Tennessee's HIV exposure or aggravated prostitution statutes are classified as violent sex offenders, regardless of whether the circumstances surrounding their arrest involved spitting, biting, or offering oral sex (7). (Prior to July 1, 2011, persons who were convicted of aggravated prostitution were classified as sex offenders rather than violent sex offenders.) Sex offenders must register with Tennessee's sex offender registry for a minimum of 10 years (7). Their information is provided to a variety of entities including local schools and law enforcement agencies. The activities of sex offenders are regulated and monitored. Failure to satisfy registration or reporting requirements is a Class E felony.

METHODS

Individual case reports were obtained for 27 arrests (25 persons) for HIV exposure (1) and 25 arrests (23 persons) for aggravated prostitution (2) between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2010. Reports included arrest records, case summaries, and affidavits of complaint. Each case report included the defendant's name, gender, race, date of birth, charges incident to arrest, prosecuting attorney, defense attorney (and whether the defense attorney was court appointed), context of arrest, complaining witness (if any), case disposition, and penalty (if any). These data were extracted, coded, and entered into a data analysis program (SPSS 15.0). Descriptive statistics were calculated (e.g., frequencies and cross tabs) for categorical data and median, mean, standard deviation, and range for numerical data. The statistical significance of intergroup differences was assessed using Fisher's Exact test for categorical data and the Mann-Whitney U-test for numerical variables. The alpha level for statistical significance was set at .05 for all analyses.

Researchers obtained Tennessee's relevant laws using traditional legal research methods. The Institutional Review Board at the first author's institution determined that this research was exempt from human subjects review.

RESULTS

HIV Exposure Cases

The following describes arrest records, case summaries, and affidavits of complaint for persons charged with violating Tennessee's HIV exposure statute (1) from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2010 in the Nashville prosecutorial region.

Arrests and Timeframe

Between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2010, 25 persons in the Nashville prosecutorial region were formally charged with violating Tennessee's HIV exposure law. Two of these individuals were charged with violating the HIV exposure statute more than once during this period, bringing the total number of charges to 27. Another individual who was arrested for HIV exposure during this timeframe was arrested two years prior for aggravated prostitution.

The earliest charge was filed January 3, 2000. The most recent was November 7, 2010. Charges were ultimately dismissed in more than one-third of the HIV exposure cases.

Defendants

The majority of persons charged with HIV exposure were male (74%) and white (56%). The median age of defendants was 36 years old. Ages ranged from 23 to 56 years old. As an indicator of social economic status, public defenders represented the defendants in two-thirds of the cases. Information on counsel was not provided in four cases. Three defendants were homeless. (Please see Table 1.)

Table 1.

Defendant & Complaining Witness Characteristics

| HIV Exposure | Aggravated Prostitution | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Defendant | ||||

| Male | 20 | 74% | 8 | 32% |

| Female | 7 | 26% | 17 | 68% |

| White | 15 | 56% | 13 | 52% |

| Blacka | 12 | 44% | 12 | 48% |

| Age mean standard deviation (range) | 36 sd 8.76 (23-56) | 37 sd 5.96 (25-49) | ||

| Had a public defenderb | 17 | 74% | 20 | 87% |

| Homelessc | 3 | 11% | 7** | 30% |

| Complaining witnessd | ||||

| Male | 15 | 58% | n/a | n/a |

| Female | 11 | 42% | n/a | n/a |

Characteristics of HIV exposure defendants did not differ from the demographic profile of PLWH in Nashville except in terms of gender.

Attorneys for four HIV exposure defendants and two aggravated prostitution defendants were unknown.

Two additional defendants had no home address provided.

Gender of one complaining witness was unknown.

Complaining Witnesses

Just over half (56%) of the complaining witnesses in HIV exposure cases were male. The gender of one complaining witness was unknown. (For details on defendant-complaining witness pairs, please see Table 2.)

Table 2.

Sexual HIV exposure cases: Defendants’ gender and race, complaining witnesses’ gender, whether defendant and complaining witness were in an on-going relationship at time of the alleged exposure, and case outcome

| Number of casesa | Race of defendant | On-going relationship/ Not on-going relationship | Case outcome: convicted of a crime/not convicted of a crime | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male defendant/Female complaining witness | 8 | 6 black | 5 ongoing relationship 1 not an ongoing relationship |

4 guilty, 1 dismissed 1 guilty |

| 2 white | 0 ongoing relationship 2 not an ongoing relationship |

1 guilty, 1 dismissed | ||

| Male defendant/Male complaining witness | 3 | 0 black | ||

| 3 white | 1ongoing relationship 2not an ongoing relationship |

1 dismissed 1 guilty lesser charge, 1 dismissed |

||

| Female defendant/Male complaining witnessb | 4 | 4 black | 3 ongoing relationship 1 not an ongoing relationship |

1 guilty, 1 guilty lesser charge, 1 dismissed 1 guilty |

| 0 white |

A case involving sexual contact with a child was not included in this table.

There were no sexual exposure cases between females.

Nonsexual Incidents

Eleven of the twenty-seven arrests for HIV exposure (41%) involved scratching, spitting (some with saliva, some with saliva mixed with blood), biting, or flinging or splattering blood. (Please see Table 3.) In ten of the eleven cases, the complaining witnesses were police officers (8) or hospital emergency staff (2). Another case involved an individual biting another person during a conflict. HIV transmission was not alleged in any of these cases, although one emergency department staff person reportedly was “treated for HIV exposure” after an HIV-positive defendant spit on her. In two cases, the defendants were charged with attempting to expose another to HIV (in both cases, the “others” were police officers); there was no transfer of bodily fluid.

Table 3.

HIV Exposure Offenses, Behaviors, Dispositions, & Penalties

| Offenses | Number of cases | Penalties/ Sentencesa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission alleged? | ||||||

| HIV Exposure | Dismissed | Non-HIV penalty | HIV-penalty | Range | ||

| Non-sexual | 11 | |||||

| Spitting, scratching | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 months – 11 months & 29 days |

| Biting, blood splatter | 7 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 years |

| Sexual | 16 | |||||

| Consensual (unprotected vaginal or anal sex) | 9 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 11 months 29 days – 8 years |

| Consensual (no data on behavior or condom use) | 6 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 years – 4 years |

| Sexual exposure of child | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 years |

| Total | 27 | 3 | 11 | 7 | 9 | |

Actual sentences are reported. In some cases, sentences were suspended; however several individuals violated the conditions of their probation and subsequently served suspended terms.

Most of the nonsexual exposure cases involved individuals resisting arrest or incarceration (73%). In several of these cases, defendants reportedly threatened to expose police officers to the virus or implied, after contact with the officer, that he or she would become infected with HIV.

The defendants in the majority of the nonsexual exposure cases (64%) were intoxicated or described as highly agitated and/or impaired when the incident occurred. In two cases, defendants were in medical facilities being treated for injuries due to prior altercations. Another defendant became combative while being transported by medics after being injured in an assault. Two defendants were described as having self-inflicted head lacerations while resisting arrest or detention. Another defendant, whom officers confronted as he was displaying a sign saying “homeless, hungry vet,” reportedly attempted to cut his wrist in order to avoid going to jail.

Disclosure of HIV Status

HIV exposure statutes are unusual when compared to most criminal laws because these statutes require arresting officers or prosecutors to be aware of defendants’ private health information. Five defendants (45%) reportedly disclosed to officers that they had HIV in threats to expose the officers to the virus. In another case, the officers became aware that the defendant had HIV because the defendant informed the hospital emergency department staff of his HIV infection prior to being treated. In three cases, the defendants’ HIV-positive status was known by police from frequent interactions with the defendants. In a fourth case, the officers were aware of the defendant's HIV-positive serostatus because of a prior arrest for violating the HIV exposure statute. Another defendant, who was arrested for reckless driving, reportedly began screaming, apparently unprompted, that he had HIV and had infected his girlfriend and their unborn baby.

Trends over time

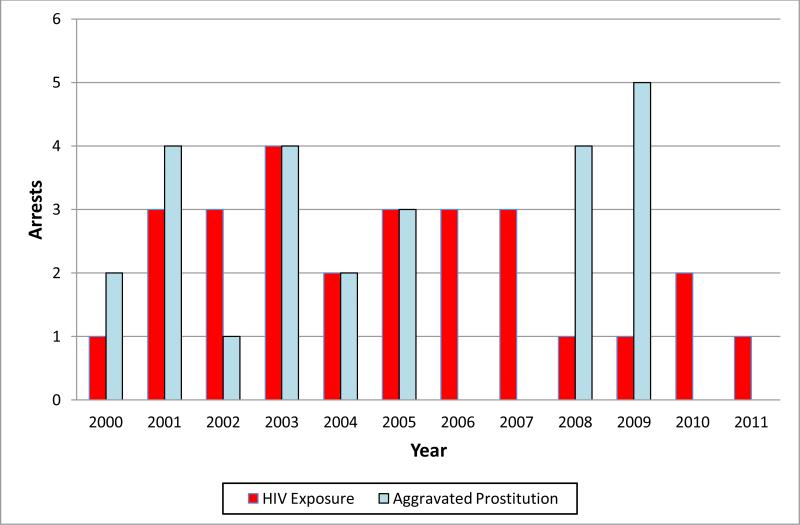

Of the ten charges involving police or hospital emergency room staff, nine occurred prior to 2007, suggesting that prosecutions of this sort diminished in the latter half of the decade. This trend was not statistically significant (p = .06). (See Figure 1.)

Arrests for HIV exposure and aggravated prostitution from 2000 to 2011 by year of arrest

Sexual Incidents

Sixteen of the twenty-seven arrests (59%) involved non-disclosed “exposure” to HIV through sex. The majority of incidents (75%) involved opposite sex partners. (Please see Tables 2 & 3.) Nine of these complaints indicated that the defendant and the complaining witness engaged in unprotected anal or vaginal sex. HIV transmission was alleged to have occurred in three of these cases. Six additional complaints did not indicate the sexual activities involved; none of these complaints alleged HIV transmission. A final case involved mouth-to-penis contact with a child (the child's mouth made contact with the defendant's penis). Again, there was no mention of HIV transmission, and a description of the sexual contact suggested that there was no transfer of bodily fluid.

Relationship between Defendant and Complaining Witness

In more than half (56%) of sexual exposure cases, the complaining witnesses and defendants did not appear to be in ongoing relationships with each other. For example, one incident involved alleged solicitation. Another incident involved a single sexual encounter in an outdoor venue. When complaining witnesses and defendants were in ongoing sexual relationships, the alleged offenses spanned seven to thirteen months. For characteristics of defendant-complaining witness pairs, please see Table 2.

Timing of Charges

The time between the dates of the alleged offenses and the dates that the charges were filed varied considerably when sexual exposure was alleged. In a few cases, the complaining witness became aware of the defendant's HIV infection but did not file charges until some other prompting event occurred. In one case, for example, the complaining witness indicated that he became infected and then found out that the defendant had HIV, but filed charges five months later, after the relationship ended. The charges were filed when both the defendant and complaining witness were co-defendants in a case involving illegal drug use and drug possession.

Disclosure of HIV Status

In most cases involving sexual exposure in an ongoing relationship, the complaining witness discovered the defendant's HIV infection through friends or family of the defendant, rather than from the defendant directly. The case reports also provide some evidence about the circumstances surrounding defendants’ failure to disclose. In one case, the complaining witness reported that she directly asked the defendant, prior to engaging in sex, if the defendant had HIV. When directly asked, the defendant reportedly denied having HIV, although he had been diagnosed prior to this incident. In another case, when the complaining witness told the defendant that she had become aware that he was putting her at risk for HIV infection, the defendant was reportedly “indifferent.”

Other defendants attributed their failure to disclose to fear of rejection. For example, one individual, when asked by the complaining witness why he did not disclose that he had HIV, reportedly answered “Because women generally do not want to be in a relationship with HIV-positive partners.” Another defendant attributed her failure to disclose her HIV-positive status to an incorrect assumption. The defendant reported that she assumed that a mutual friend had informed the complaining witnesses that she had HIV.

Evidence of Intent to Harm

Evidence in the case reports related to nondisclosure, above, includes one defendant who reportedly lied about his HIV status when asked directly by a prospective sex partner. Others failed to disclose, whether for instrumental reasons or mistaken assumptions. While these acts, including outright lying and may be blameworthy to varying degrees, the records revealed no evidence that any of the defendants in sexual exposure cases intended to infect or to harm the complaining witnesses.

Dispositions

Sixteen of the twenty-seven HIV exposure cases (60%) resulted in a conviction. Nine of the convictions were for HIV exposure and seven were convictions for a lesser charge. (Please see Table 3.)

Nonsexual Incidents

Of the eleven nonsexual exposure charges, only one case ended in conviction for violating the criminal HIV exposure statute (intoxicated man, self-inflicted laceration). One case was dropped, five cases were dismissed, and four ended with defendants being found guilty of lesser charges. (Please see Table 3). Convictions on lesser charges included misdemeanor assault, assault with bodily injury, and assault with offensive or provocative contact.

Sexual Incidents

Of the sixteen sexual exposure cases, eight cases ended in a guilty verdict for HIV exposure, two ended in guilty verdicts for a lesser charge (reckless endangerment), and six were dismissed. Defendants in over half of the cases described as involving unprotected sex were convicted on HIV exposure charges; one was found guilty of reckless endangerment, and charges were dismissed for the remaining three cases. Of the three cases where HIV transmission was alleged, one ended in a guilty verdict and two were dismissed. (Please see Table 3.)

Sentences

Sentences for HIV exposure ranged from one month to eight years’ incarceration. The median was 30 months. Sentences for nonsexual exposure ranged from one month to three years with a median sentence of four months, while those for sexual exposure ranged from one to eight years with a median sentence of forty-two months. (See Table 3.) Sentences did not differ by the gender of the defendant or the gender of the complaining witness; however, individuals who were black received significantly longer sentences than those who were white (z = −2.078, p = .038). This disparity in sentencing may be due, in part, to the type of offense (i.e., sexual or nonsexual). Persons who were black were more likely to be convicted of criminal HIV exposure related to a sexual interaction than persons who were white (Fisher's exact test, p = .035), and penalties for sexual exposure are significantly longer than penalties for nonsexual exposure (z = 2.784 p = .003).

The convictions for HIV exposure that received the most severe penalties were unprotected sexual exposure with alleged transmission (five years); followed by unprotected sexual exposure within an ongoing relationship, no transmission alleged (eight years and five years); unspecified sexual act within an ongoing relationship, no transmission alleged (four years); and unprotected sex with a casual sex partner (three years). There was one anomaly--an HIV exposure conviction involving blood splatter on a police officer while the defendant was resisting arrest. The defendant was charged with two counts, both of which received three-year sentences. The sentence for the second count was suspended; however, the defendant subsequently violated probation and served the term. (See Table 3.)

In some cases, judges included special orders as part of the case disposition. In three cases, the judge included an order that the defendant stay away from the complaining witness. In two cases, the judge ordered the defendant to participate in a support and secondary transmission prevention program offered at a local AIDS service organization.

Aggravated Prostitution

Arrests and Timeframe

Between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2010, 23 persons in the Nashville prosecutorial region were formally charged with violating Tennessee's aggravated prostitution statute (2). Two of these individuals were charged with violating the statute more than once during this period, bringing the total cases to 25. One individual who was arrested for aggravated prostitution between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2010 was also arrested for criminal HIV exposure in the same timeframe (see HIV exposure, above).

The earliest charge was filed May 11, 2000. The most recent was May 26, 2010. The annual arrests for aggravated prostitution were not consistent over time. For example, there were no arrests between 2007 and 2008, but there were three arrests in 2006 and four arrests in 2009. (See Figure 1.)

Six of the twenty-three persons (26%) arrested for aggravated prostitution between January 1, 2000 and December 1, 2010 had been previously arrested for HIV-specific charges. One had been arrested 3 times, one “multiple times,” and another 2 times. This last defendant had also been arrested prior to January 1, 2000 for HIV exposure.

Defendants

The majority of persons charged with aggravated prostitution were female (68%) and white (52%). The median age of defendants was 37 years old. Ages ranged from 25 to 49 years old. Public defenders represented the defendants in 80% of the cases. Information on defense counsel was not provided in two cases. Seven defendants were homeless (30%), and two others had no home address listed on court records (9%). (See Table 1).

Incidents: Specific Behaviors Alleged

Of the 17 cases for which there is information on the sexual behavior solicited, 13 cases involved solicitation for oral sex, 3 cases involved solicitation for vaginal intercourse, and 1 case involved solicitation for condom-protected anal sex. (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Aggravated Prostitution Offenses, Behaviors, Dispositions, & Penalties

| Offense | Number of Cases | Penalties/ Sentencesa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggravated Prostitution | Dismissed | Non-HIV penalty | HIV penalty | Range | ||

| Transmission alleged? | ||||||

| Solicited only oral sex | 13 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 30 days - 6 yearsb |

| Solicited protected anal or vaginal sex | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11 months & 29 days |

| Solicited anal or vaginal sex condom use unspecified | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 years – 5 years |

| Solicited act unspecified | 8 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 30 days – 2 years |

| Total | 25 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 9 | |

Actual sentences are reported. In some cases, sentences were suspended; however several individuals violated the conditions of their probation and subsequently served suspended terms.

The sentence of one defendant was unknown.

Incidents: Circumstances of Arrests

In more than half of the aggravated prostitution arrests (14 arrests, or 56%), the defendants were charged after solicitation of an undercover police officer or police representative. Two of these defendants were identified by police after they posted advertisements on the Internet. Seven defendants were arrested after being seen “flagging down cars,” “leaning into cars,” or loitering in areas known for prostitution. The additional two arrests resulted from unrelated calls to the police.

In nearly half (44%) of the aggravated prostitution cases, defendants were charged with illegal drug-related charges along with the aggravated prostitution charge. One of these individuals was described as “high” when arrested; when asked for her identification, she handed the officer a crack pipe. Another individual was arrested after offering to exchange sex for crack cocaine. Two individuals were charged with possession of drug paraphernalia because they had syringes.

Disclosure of HIV Status

In ten aggravated prostitution cases (40%), the defendants themselves disclosed to police that they had HIV. In four additional instances, police officers were familiar with the defendants from previous interactions and were aware that defendants were HIV-positive. In another instance, the individual was known to be HIV-positive because he had told an officer the previous week that he did not engage in prostitution anymore because he “knew he was HIV-positive.”

Evidence of Criminal Intent

There was no evidence that any of the defendants charged with aggravated prostitution intended to infect or to harm the complaining witness.

Dispositions

Ninety-two percent of aggravated prostitution cases (23 out of 25) resulted in a conviction. Nine cases (41%) resulted in conviction for aggravated prostitution. Fourteen (56%) resulted in convictions for a lesser charge (the majority for misdemeanor prostitution), and one (5%) resulted in conviction for aggravated assault. Charges were dismissed in two of the twenty-five arrests for aggravated prostitution. (See Table 4.)

Sentences

Sentences for aggravated prostitution ranged from two to six years’ incarceration. The median sentence was three years. Sentences for misdemeanor prostitution ranged from 30 days to 11 months and 29 days (the maximum for a misdemeanor). The median was nine months. (See Table 4). In one case, the judge ordered the defendant to undergo drug treatment. In another case, the defendant was ordered to attend a support group for persons living with HIV. One individual was required to complete 40 hours of community service after his sentence for reckless endangerment was suspended. Another individual was required to undergo testing for sexually transmitted infections.

DISCUSSION

HIV-specific criminal laws are regarded as highly suspect both in the US and elsewhere in the world (8-11). HIV exposure laws are especially problematic because these laws have the potential to be enforced in ways that reinforce stigma and discrimination, undermine national and global HIV prevention messages, and violate human rights. The laws are usually applied by persons who have no experience in HIV risk assessment, and they are often applied to persons who are so marginalized from mainstream society that they have little recourse when accused. Furthermore, being charged with an HIV-specific offense, whether one is prosecuted or the case is dismissed, reveals one's private health information to all parties involved in the complaint and may memorialize one's HIV-positive status in public records. There is great potential for abuse of these statutes.

Although the number of prosecutions in the Nashville jurisdiction is too small and the data gleaned from the affidavits of complaint too limited for extensive analyses, these data do provide important insights into how these laws have been implemented in one jurisdiction for more than a decade. The results are not generalizable, but they are informative. The data suggest that previous research may have significantly underestimated the incidence of arrests and convictions for HIV-specific crimes. There were 52 HIV-related arrests over 11 years in the Nashville region, while the landmark study of enforcement prior to this identified only 316 cases in the US over 15 years (3). The data raise numerous questions and suggest that further analysis of the enforcement of HIV-specific crimes could reveal that far more individuals have been charged and/or convicted of these offenses then previously estimated.

What we can say ...

No Risk or Low Risk Acts

From 2000-2010, a surprising proportion (41%) of the charges for criminal HIV exposure in the Nashville prosecutorial region were for nonsexual behaviors that pose minimal or no risk of HIV transmission. None of these charges alleged HIV transmission. The decline in arrests for nonsexual exposure after 2007, however, is encouraging. It is also encouraging that only one of the eleven HIV exposure arrests that stemmed from a nonsexual incident resulted in conviction for HIV exposure. It is possible that there may be some sensitivity to transmission risk in the adjudication of these cases. Still, the persistence of any HIV exposure arrests based on behaviors that pose no or negligible risk of HIV transmission suggests misunderstanding or misuse of the law. At the very least, these arrests suggest that police officers and prosecutors interpret the statutory requirement of “significant exposure” much differently than infectious disease experts.

Although Tennessee's aggravated prostitution statute does not require “significant risk” of HIV transmission, or even any physical contact, it is important to note that more than half of those defendants arrested for aggravated prostitution had only offered oral sex. The risk of HIV transmission from oral sex is very low, on the order of 0.04% per act of oral sex (12). This estimate probably overstates the risk in the Nashville cases because the 0.04% estimate was based on cases in which the HIV-infected person ejaculates into the mouth of another, rather than the other way around (i.e., an HIV-infected prostitute performs oral sex on a male) (13). Although defendants violate the letter of the aggravated prostitution law by having HIV infection and offering to trade oral sex for money, in this case the intended act poses minimal risk of HIV transmission. Use of the aggravated prostitution provisions, with their significantly enhanced penalties, for the very low risk activities described in many of the prostitution cases does not appear to be based on either actual risk or evidence of intent to harm.

Substance Abuse and Mental Impairment

The summaries of both HIV exposure and aggravated prostitution cases suggest that substance abuse and other impairments played an important role in these cases. In nearly half of the aggravated prostitution arrests, the defendants were also charged with drug offenses or possession of drug paraphernalia. At least one defendant was under the influence when arrested and at least one other was arrested while attempting to exchange sex for drugs. Likewise, three HIV exposure cases resulted from defendants resisting arrest after being charged with an alcohol-related offense such as driving under the influence or public intoxication. The summaries suggest further that some of the defendants suffered from mental illness or other cognitive impairment.

Homelessness

The aggravated prostitution cases highlight the problem of homelessness among persons living with HIV. Nearly one-third of persons charged with aggravated prostitution were homeless. Another 9% had no home address listed, suggesting that they too were homeless or unstably housed. In addition, three persons arrested for HIV exposure were homeless.

Recidivism and Intractable Behaviors

Several defendants were arrested on more than one occasion for HIV-related crimes. In one case, a defendant was arrested and charged with aggravated prostitution in two separate instances in one week. In another case, the defendant was arrested twice in four months. Other defendants’ arrest reports noted that they had extensive criminal records or drug histories. Several defendants were described as “known to police.” In some cases, police were familiar enough with the defendants to know they were infected with HIV.

Police Response to Defendants who Resist Arrest

The majority of HIV exposure cases that involved spitting, scratching, or blood spattering occurred when defendants were intoxicated, agitated, or otherwise impaired. Most were resisting arrest. Many were being restrained prior to the incident that resulted in the HIV exposure charge, and some were described as having inflicted serious wounds upon themselves. Their resistance could have put themselves and arresting officers in danger, but not from HIV infection.

Although these data do not identify what specific factors drove police and prosecutors to arrest and bring felony charges against these defendants, the picture that emerges is of police and emergency responders who have difficult and sometimes threatening encounters with persons who are intoxicated, mentally ill, or otherwise impaired. The police may perceive few other local options or resources for dealing with people who exhibit these types of behaviors. Still, several defendants seemed as if they might be better served through community services such as drug treatment, supportive housing, intensive case management, etc., than through the criminal justice system. Judges ordered some defendants to seek services or to attend support groups. Unfortunately, in at least one case, the convicted individual left a court-ordered treatment facility and was subsequently incarcerated.

What we can't tell from these cases...

Role of Empirical Evidence and Public Health

Public health sciences and technology are relevant to criminal HIV exposure cases in several ways, but these records provide little evidence of their role in the Nashville cases. Public health personnel might, for example, advise police or emergency responders who are worried about their risk after exposure. If public health personnel could provide an objective assessment of risk, defendants might not be charged with HIV-specific crimes in cases where the actual risk of transmission was minimal or non-existent.

Extensive empirical research quantifies the risk of various types of exposure to HIV and the impact of preventive measures such as condom use. Although the cases reviewed here included a variety of exposure activities, there is no way to tell from these records whether the police, prosecutors, or defense attorneys were aware of this body of research or whether they considered it in any way in the process of charging, prosecuting, or defending these cases. However, the fact that several cases involving behavior that posed minimal risk of transmission resulted in convictions and incarceration suggest that, at least in some cases, evidence of the actual risk of transmission was not considered or, if used, was not persuasive.

HIV transmission was alleged in three of the HIV exposure cases. Although the technology exists to establish whether one individual was a possible source of another's infection and also to prove conclusively that a defendant could not have been the source of another's infection, we cannot tell from these case records whether such evidence was sought or used at trial.

It is troubling that in at least one case, justice officials subpoenaed health department records to establish that a defendant was aware of his HIV infection. This inter-agency cooperation could seriously diminish client confidence in the health department and ultimately harm HIV prevention efforts.

Role of Race, Gender and Sexual Orientation

Defendants in the Nashville cases were male and female, heterosexual and homosexual, white and nonwhite. Complaining witnesses, too, were diverse in terms of race, gender, and apparent sexual orientation. As mentioned above, there were proportionally more women among those arrested for HIV exposure than there were among persons living with HIV in Nashville. Although there was no statistically significant difference in the racial characteristics of those arrested for HIV exposure and the racial characteristics of persons living with HIV in Nashville, analyses did reveal a significant difference in sentencing by race. (See below.) Beyond this it is difficult to tease out the possible role that race, gender, or sexual orientation may have played in these criminal cases.

Sentencing

None of the Nashville cases resulted in the extraordinarily long sentences found in earlier studies of HIV prosecutions (many sentences for >10 years, instances of sentences for 60 years, and even for life) (3,4). However, among the 30 overall convictions there were still sentences for eight years (HIV exposure) and six years (aggravated prostitution). Moreover, at least one defendant received a three-year sentence for spitting/scratching and another received a six-year sentence for solicitation of oral sex. Whether these sentences are proportionate to other crimes of similar gravity is difficult to answer. We also do not know the role that previous convictions may have played in the final sentence. We can say, however, that a three-year sentence for splashing blood while resisting arrest—a behavior that posed minimal risk—seems disproportionate, as does a six-year sentence for solicitation of oral sex.

The sentences of black individuals arrested for HIV exposure were significantly more severe than the sentences of their white counterparts. This racial disparity may point to serious flaws in the adjudication process. Black defendants were significantly more likely than white defendants to be prosecuted for sexual (as opposed to nonsexual) exposure, and sexual exposure cases received more severe sentences. Sentences for HIV-specific offenses should be systematically compared to those handed down for other offenses to evaluate whether sentencing reflects prejudice or fear of contagion or more than the defendants’ criminal motivation or actual risk to society.

Police and Corrections Officers’ Behavior

The data available about nonsexual exposure and aggravated prostitution cases are inherently biased in that they represent the arresting officers’ depiction of the alleged incidents. Defendants’ depictions of events are not recorded. It has been suggested that in some cases, police or corrections officers will use excessive force or otherwise mistreat an individual and then charge the individual with a crime in order to diminish his or her credibility and/or deter the victim/defendant from reporting the mistreatment (14). With HIV exposure charges, it may also be possible that the defendant disclosed his or her seropositive status to police officers in an effort to fend off physical abuse. We cannot know if this occurred in any of the nonsexual exposure cases described here.

Impact of Sex Offender Status

Although we know that the statutory consequences of being classified as a “violent sex offender” under Tennessee law are extensive, we have no way of knowing the actual impact on the lives of the 17 individuals here that were convicted of either HIV exposure or aggravated prostitution. We do not know if they have been forced out of housing or had difficulty finding new housing; we do not know if they have been exposed to their friends and families through the state sex offender registry, or if this has had a negative impact on their employment, or education. We do not know what impact it had on their families, since some of them are likely parents.

Summary of Relevant Literature

HIV exposure Law Studies

Considerable research attention has been dedicated to the study of HIV exposure laws and more generally, the criminalization of HIV exposure. Along with studies of the enforcement of HIV exposure laws (described below), researchers have addressed topics such as attitudes toward the criminalization of HIV exposure (15-21), awareness of pertinent laws (15, 18-20, 22-24), potential effectiveness of these laws as a structural-level HIV prevention intervention (3, 19, 22-26) and inadvertent negative effects of the laws (15-17, 20-25, 28).

Comparison with similar studies

There is no central system in the US or, to our knowledge, in any single state within the US, to which arrests for HIV exposure or aggravated prostitution are reported. Therefore, few studies have been able to examine comprehensively and systematically the characteristics of defendants and the contexts of their arrests for HIV-specific offences in any given jurisdiction.

By tracking news media and court records, Lazarini et al. identified 316 distinct HIV-related criminal cases in 39 US states and territories between 1986 and 2001 (3). Of these cases, 165 ended in conviction on HIV-related charges. In 21 additional cases, HIV was the basis for an enhanced penalty after conviction for another crime, such as sexual assault. (In one case, a defendant received both a conviction on an HIV-specific charge and a sentence enhancement.) The sentences in these cases were considerably longer (e.g., the average minimum sentence of those who received less than a life sentence was 14.3 years) than sentences in the Nashville region. Characteristics of defendants were not analyzed.

Using a similar method of tracking media and published court cases, Positive Justice Project attorneys identified over 350 criminal HIV exposure cases spanning 2008-2011 in 36 states in the nation (4). However, the Positive Justice Project attorneys cautioned that their case summaries are meant to be illustrative rather than exhaustive. As such, statistical analyses were not conducted.

Hoppe identified 56 convictions for violations of Michigan's criminal HIV exposure law between 1992 and 2010 (27). Sufficient data were available in 30 of these cases for statistical analyses. Although the Michigan and Nashville studies differ in significant ways (e.g., the Michigan data reflect adjudicated cases while the data in the present study reflect arrests through final disposition in most cases), there were similarities in the findings from both studies. Few of the cases in Michigan alleged transmission, which is consistent with findings in Nashville (2 of the 30 cases analyzed in Michigan and 3 of the 52 arrests in Nashville alleged transmission), several cases in both studies were based on incidents involving little to no risk of HIV transmission, and few cases in either study involved more than one complaining witness. In both Michigan and Nashville there was an overrepresentation of African-American men with female partners among those convicted for an HIV-specific offense when compared to surveillance data on incident infections. The average criminal sentence for those convicted of a crime (whether an HIV-specific crime or a lesser charge) was less than three years in both studies. In Michigan, as in the Nashville region, a substantial proportion of defendants appeared to suffer from mental illness or drug addiction.

Outside of the US, Mykhalovskiy in Canada found that a large number of prosecutions were among black, immigrant men (28). In Nashville, on the other hand, women were overrepresented in arrests for HIV exposure when compared to the epidemiological profile of persons living with HIV in the region (defendants in aggravated prostitution cases were not included in these analyses because, as expected, the majority were women). Those arrested in Nashville did not differ significantly by race.

CONCLUSIONS

Ostensibly, HIV-specific criminal laws are enacted to reduce the incidence of new HIV infections (11); however, the enforcement of the laws in the Nashville prosecutorial region suggests that HIV exposure and aggravated prostitution statutes rarely address situations where HIV transmission is likely. In fact, experts in infectious disease transmission might argue that few cases involved even the “significant exposure” required by the statute.

One argument that has been made in favor of adopting and maintaining HIV-specific criminal statutes (even among some who otherwise oppose such laws) is that the statutes should be available to punish exceptionally heinous behavior, such as cases of intentional transmission of HIV or cases where multiple individuals are infected. However, based on this analysis of 11 years of cases from one jurisdiction, that is not how these laws are being used.

Few, if any, of the arrests for HIV exposure or aggravated prostitution involved the malice or moral deficiency that some imagine motivates HIV-positive persons who “expose” uninformed sex partners to HIV. For example, in only one case does the record suggest that the defendant lied when asked directly by a prospective sex partner whether he had HIV. In another case the defendant was characterized as “indifferent” when confronted about having sex with an uninformed partner.

The majority of people charged and convicted for these offenses are poor, from marginalized groups, and often suffer from drug dependency or mental illness, or both. Many of the HIV exposure arrests address fairly specific police interactions with defendants whose chaotic lives seem to make them unresponsive to efforts to address their behavior through the criminal law. Their actions seem too disorganized and too ineffective to be malicious.

The aggravated prostitution cases highlight a similar dynamic. The recidivism is alarming, not so much because the defendants put others at risk of HIV transmission, but because the defendants seem to act out of desperation. Drug addiction, homelessness, and other concurrent problems may leave defendants feeling they have no other means of survival.

Using HIV exposure and/or aggravated prostitution laws in these cases is inappropriate and inadequate for at least two reasons. First, these laws are ill-suited because the behaviors punished have little to do with transmission risk and are not motivated by criminal intent. Second, the defendants are likely to engage in repeat behavior if their addiction and mental health problems remain unaddressed. Many of these defendants have complex medical, behavioral, and social problems that the criminal justice system is ill-suited to solve. Identifying better options, both for police trying to deal with dangerous or recalcitrant defendants and for defendants struggling with multiple problems, should be a priority of public health policy-making that seeks to reduce new HIV infections and potential negative consequences of these laws. The development of prosecutorial guidelines might help to focus enforcement of these laws on incidents where an individual acts with intention to transmit HIV to another.

Examination of these 52 cases points to disturbing issues both among the actual findings and, to an even greater extent, among the questions left unanswered. Although individual cases of undisclosed exposure to HIV receive attention, troublesome patterns and practices may not be detected without analysis of additional, comprehensive data sets from a strategic sample of jurisdictions. Furthermore, many of these cases highlight the chaotic and often desperation-filled contexts in which persons are arrested for HIV-specific crimes. Research using a systems approach to explore interactions between the criminal justice and public health systems would be helpful.

ACKOWLDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants R01MH091875 and P30-MH52776 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Dawn Deaner, Nashville Public Defender's Office, and Kevin Brown, Linda Burney, and Steven Pinkerton, Medical College of Wisconsin, Center for AIDS Intervention Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Criminal exposure of another to HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), hepatitis B virus (HBV), or to hepatitis C virus (HCV). Tenn. Code Ann. 2012:§39–13-109. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggravated prostitution. Tenn. Code Ann. 2012:§39–13-516. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazzarini Z, Bray S, Burris S. Evaluating the Impact of Criminal Laws on HIV Risk Behavior. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30(2):239–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2002.tb00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennet-Carlson R, Faria D, Hanssens C. [10/24/12];Ending and Defending Against HIV Criminalization: A Manual for Advocates. (1st ed). State and Federal Laws and Prosecutions. (1st ed). 2011 1 Fall 2010, with cases through December Available at: www.hivlawandpolicy.org/resources/download/564. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Authorized terms of imprisonment and fines for felonies and misdemeanors. Tenn. Code Ann. 2012:§40–35-111. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prostitution. Tenn. Code Ann. 2012:§39–13-513. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tennessee Sexual Offender and Violent Sexual Offender Registration. Verification, and Tracking Act of 2004. Tenn. Code Ann. 2012:§40–39-201-215. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors. [10/24/12];Understanding State Departments of Health and Corrections Collaboration: A Summary of Survey Findings – Part II and Strategic Guidance towards ending criminalization-related stigma and discrimination. 2011 Available at www.nastad.org/HIVC/decriminalization_findings.pdf.

- 9.UNAIDS [10-24-12];Brief Policy: Criminalization of HIV Transmission. 2008 Available at www.data.unaids.org/.../20080731_jc1513_policy_criminalization_en.pdf.

- 10.Burris S, Cameron E. The Case Against Criminalization of HIV Transmission. JAMA. 2008;300(5):578–581. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galletly CL, Pinkerton SD. Conflicting messages: How criminal HIV disclosure laws undermine public health efforts to control the spread of HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(5):451–461. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vittinghoff E, Douglas J, Judson F, Mc Kirnan D, MacQueen K, Buchbinder SP. Per-Contact Risk of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Transmission between Male Sexual Partners. American J Epidemiol. 1999;150(3):306–311. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily M. Systematic Review of Orogenital HIV-1 Transmission Probabilities. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:1255–1265. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman H. To Protect and Serve? Trial. 2011;47:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodds C, Bourne A, Weait M. Responses to criminal prosecutions for HIV transmission among gay men with HIV in England and Wales. Reproductive Health Matters. 2009;17(34):135–145. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)34475-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodds C, Keogh P. Criminal prosecutions for HIV transmission: People living with HIV respond. Intl J STD AIDS. 2006;17:315–318. doi: 10.1258/095646206776790114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galletly CL, Dickson-Gomez JB. HIV sero-positive status disclosure to prospective sex partners and criminal laws that require it: Perspectives of persons living with HIV. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2009;20(9):613–618. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galletly CL, DiFranceisco W, Pinkerton SD. HIV-positive persons’ awareness and understanding of their states' criminal HIV disclosure law. AIDS & Behav. 2009;13:1262–1269. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9477-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horvath KJ, Weinmeyer R, Rosser S. Should it be illegal for HIV-positive persons to have unprotected sex without disclosure? An examination of attitudes among US men who have sex with men and the impact of state law. AIDS Care. 2010;22:1221–1228. doi: 10.1080/09540121003668078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Positive Women's Network [10/24/12];Diagnosis, Sexuality, and Choice: Women living with HIV and the quest for equality, dignity and quality of life in the U.S. Oakland California. 2011 Available at http://www.pwn-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/PWN-HR-Survey-FINAL.pdf.

- 21.Klitzman R, Kirshenbaum S, Kittel L, et al. Naming names: Perceptions of name-based reporting, partner notification, and the criminalization of nondisclosure among persons living with HIV. Sexuality Research & Social Policy. 2004;1(3):38–57. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galletly CL, Pinkerton SD, DiFrancesico W. A quantitative study of Michigan's criminal HIV exposure law. AIDS Care. 2011:174–179. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.603493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burris S, Beletsky L, Burleson J, Case P, Lazzarini Z. Do criminal laws influence HIV risk behavior? An empirical trial. Arizona State Law J. 2007;39:467–519. [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Byrne P, Bryan A, Woodyatt C. Nondisclosure Prosecutions and HIV Prevention: Results From an Ottawa-Based Gay Men's Sex Survey. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2012:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adam BD, Elliott R, Husbands W, Murray J, Maxwell J. Effects of the criminalization of HIV transmission in Cuerrier on men reporting unprotected sex with men. Can J Law and Society. 2008;23:143–159. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galletly CL, Glasman LR, Pinkerton SD, DiFranceisco W. New Jersey's HIV exposure law and the HIV-related attitudes, beliefs, and sexual and seropositive status disclosure behaviors of persons living with HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300664. Published on-line in advance of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoppe T. Presentation International AIDS Conference. Washington, DC: 2012. [7/25/2012]. Punishing HIV: How Michigan Trial Courts Frame Felony HIV Disclosure Cases. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mykhalovskiy E. The problem of “significant risk”: Exploring the public health impact of criminalizing HIV non-disclosure. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73:668–675. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]