Abstract

Lymphoid organ hypertrophy is a hallmark of localized infection. During the inflammatory response, massive changes in lymphocyte recirculation and turnover boost lymphoid organ cellularity. Intriguingly, the exact nature of these changes remains undefined to date. Here, we report that hypertrophy of Salmonella-infected Peyer's patches (PPs) ensues from a global “shutdown” of lymphocyte egress, which traps recirculating lymphocytes in PPs. Surprisingly, infection-induced lymphocyte sequestration did not require previously proposed mediators of lymphoid organ shutdown including type I interferon receptor and CD69. In contrast, following T-cell receptor-mediated priming, CD69 was essential to selectively block CD4+ effector T-cell egress. Our findings segregate two distinct lymphocyte sequestration mechanisms, which differentially rely on intrinsic modulation of lymphocyte egress capacity and inflammation-induced changes in the lymphoid organ environment.

INTRODUCTION

Lymphocytes continuously enter and exit secondary lymphoid organs. Local infection and inflammation can drastically change lymphocyte recirculation, increase lymphoid organ cellularity, and cause lymphoid organ hypertrophy. Triggers of this process include type I interferon (IFNα/β),1 tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α,2, 3, 4, 5, 6 bacterial lipopolysaccharide,6 peptidoglycan,7 complete Freund's adjuvant,8 interleukin (IL)-6,3 IL-1,6 prostaglandin E2,9 and complement activation.10 Lymphoid organ hypertrophy is considered to facilitate encounter of antigen-presenting cells and antigen-specific naive lymphocytes,4, 11, 12 thus enabling the efficient induction of adaptive immune responses.8, 13

However, the mechanisms that bring about lymphocyte accumulation in hypertrophic organs are poorly understood. Lymph node hypertrophy has been associated with enhanced recruitment of naive lymphocytes from blood.4, 5, 6, 8, 14, 15 In addition, lymphocyte proliferation is thought to support the increase in the total lymphocyte numbers.16, 17 Finally, lymph nodes can temporarily “shut down” lymphocyte egress in response to a variety of stimuli such as antigen, TNF-α, and IFNα/β.2, 3, 9, 10, 18 How changes in lymphocyte entry, proliferation, and egress integrate to cause lymphoid organ hypertrophy is unclear.

Lymphocyte egress from secondary lymphoid organs is an actively regulated process, which requires sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) on lymphocytes.19 Studies on IFNα/β-induced lymphopenia have linked lymphoid organ shutdown to S1PR1-mediated lymphocyte egress.20, 21 Engagement of type I interferon receptor (IFNAR) on lymphocytes upregulates early activation marker CD69. Through direct interaction, CD69 causes internalization of cell surface S1PR1, thus abrogating the egress capability of the lymphocyte.20, 22 Via this IFNAR/CD69/S1PR1 axis, systemically administered IFNα/β inducers are thought to block lymphocyte egress from secondary lymphoid organs and cause the observed loss of lymphocytes from blood and lymph.20 Without direct experimental evidence, the same mechanism has been proposed to mediate lymphoid organ shutdown during local immune responses and lymph node hypertrophy.20 Many inflammatory stimuli trigger IFNα/β production and, furthermore, TNF-α or T-cell receptor (TCR) activation also directly induces CD69 expression.20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Thus, the IFNAR/CD69/S1PR1 axis has become the paradigm to explain lymphoid organ shutdown during local immune responses.11, 25, 26

Intriguingly, lymphocyte egress has not been directly investigated in the context of localized infection and lymphoid organ hypertrophy. Efferent lymph - that is, lymph leaving secondary lymphoid organs - is difficult to access in mice and only recently, in-situ labeling techniques such as photoconversion have started to be employed to monitor cell trafficking.27, 28 In the context of lymphoid organ hypertrophy, mouse studies have relied on indirect readouts of egress such as retention of adoptively transferred cells15 upon L-selectin blockade or FTY720 pretreatment.8 However, because lymphocyte entry and exit regulation are closely linked,29 these indirect approaches do not always appropriately separate both effects. Owing to these technical limitations, the requirements for lymphocyte egress from hypertrophic lymphoid organs have not been directly addressed.

Similarly, it has not been directly investigated to which degree lymphopenia-inducing substances compromise lymphocyte egress on the organ level. CD69-deficient lymphocytes enter lymph node cortical sinuses more efficiently than CD69-proficient cells after stimulation with lymphopenia-inducing polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid (polyI:C).30 However, IFNα/β-induced lymphopenia has been suggested to rely on mechanisms other than lymphocyte sequestration—for example, increased lymphocyte attachment to vascular endothelium.21, 31 Consequently, it is unknown how representative the effects of polyI:C and other lymphopenia inducers are of the dynamics in lymphoid organs undergoing immune activation. In fact, only few studies have actually employed genuine infection models to study lymph node enlargement14, 15, 17 and it has not been shown in a full immune response to localized infection whether the IFNAR/CD69/S1PR1 axis possesses the capacity to mediate a general, organ-wide egress shutdown.11, 12, 24, 32

In this study, we use in situ labeling and intestinal lymph isolation to investigate the cellular dynamics leading to hypertrophy of Salmonella-infected intestinal Peyer's patches (PPs) and address the molecular requirements for egress from infected PPs. We report that infected PPs establish a compartment-wide egress blockade that affects all major recirculating lymphocyte populations independently of the IFNAR/CD69/S1PR1 axis. In contrast, we show that CD69 is a critical mediator of selective effector cell retention following TCR-mediated priming. Collectively, we propose that two distinct mechanisms sequester lymphocytes in secondary lymphoid organs: a first pathway, which acts through TCR and CD69 and affects the capacity of individual cells to leave the organ, and a second pathway, which is CD69-independent, encompasses the entire compartment, and likely relies on changes in both the lymphocyte and lymphoid organ environment.

RESULTS

Hypertrophy of Salmonella-infected PPs results from reduced lymphocyte egress

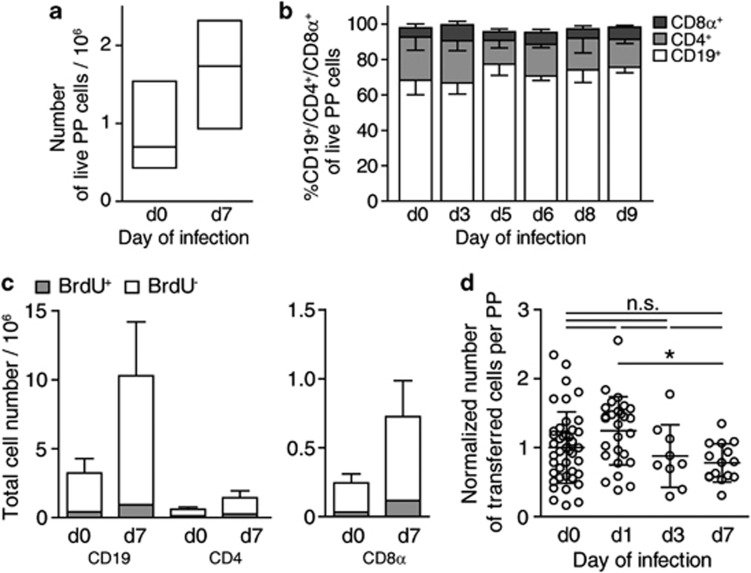

Intestinal PPs are secondary lymphoid organs that participate in homeostatic lymphocyte recirculation, release naive lymphocytes into efferent lymph in an S1PR1-dependent manner,19 and become hypertrophic during infection. The experimental model we used to investigate PP hypertrophy is an oral infection with an attenuated strain of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium (SL1344ΔaroA). This strain enters PPs, established infection and spreads to mesenteric lymph nodes (mLNs), liver, and spleen.33 Seven days after infection, PPs had visibly enlarged in size and contained on average 1.5-fold more cells than PPs from non-infected control mice (Figure 1a). The lymphocyte composition in PPs did not change substantially during the first week of infection (Figure 1b), suggesting that PP hypertrophy does not result from an increase in frequency of a particular subpopulation but from the accumulation of all major PP cell types. Consistently, PP lymphocyte populations did not strongly incorporate the thymidine analog 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine throughout the infection period, indicating that cell proliferation did not substantially contribute to lymphocyte accumulation in infected PPs (Figure 1c). To address whether lymphocyte entry into infected PPs was increased and contributed to PP hypertrophy, we performed short-term adoptive transfer experiments. Congenically marked lymphocytes were transferred intravenously to non-infected or infected recipients on days 1, 3, or 7 of infection. The number of transferred cells in PPs was determined at 2 or 4 h post transfer. At these early time points, the number of transferred cells monitors entry and is not affected by egress.34 Entry of transferred cells into infected PPs was not significantly enhanced in infected compared with non-infected recipients (Figure 1d), suggesting that changes in lymphocyte recruitment are not a major contributor to lymphocyte accumulation in infected PPs.

Figure 1.

Lymphocyte composition and turnover during infection-induced Peyer's patch (PPs) hypertrophy. (a) Cell counts in non-infected (d0) or Salmonella-infected (d7) PPs. Median+inter-quartile range (IQR) of 61 and 89 individual PPs from 10 to 12 mice per group, four independent experiments. (b) PP cell composition, determined using flow cytometry. Mean+s.d. of individual PPs from total 45 mice, eight independent experiments. (c) 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation into PP cells during infection. Non-infected (d0) or infected (d7) mice were given BrdU in the drinking water for 7 days. One of two independent experiments, mean+s.d. of four mice per group, PP pools analyzed. (d) Lymphocyte entry into infected PPs. A total of 107 cells were transferred to non-infected or infected congenic recipients. PPs were analyzed 2 or 4 h later. Individual PPs from nine (d0), six (d1), or three (d3, d7) mice per group, four independent experiments. Numbers normalized to average number of transferred cells in non-infected PPs. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple comparison test.

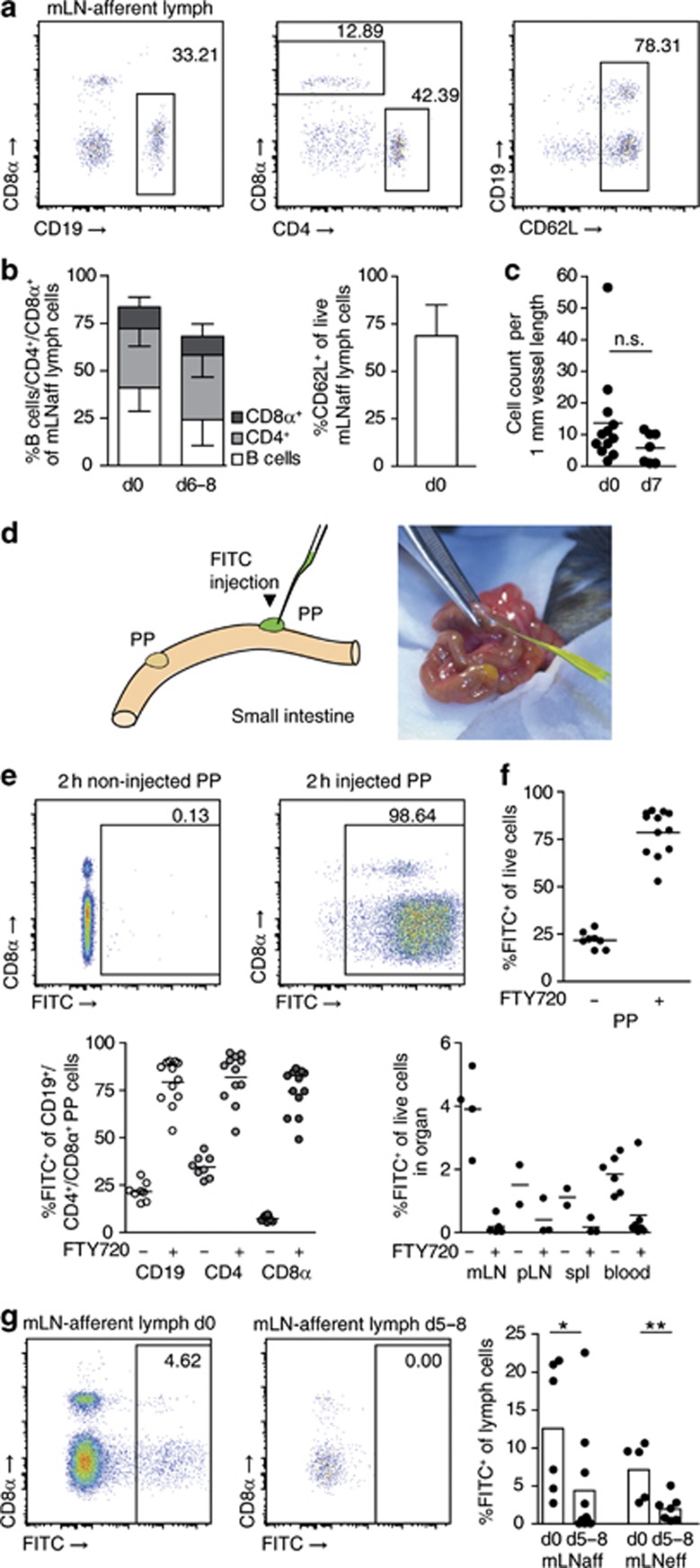

Besides lymphocyte entry and proliferation, the rate of lymphocyte egress determines lymphoid organ cellularity. We therefore addressed whether infection altered lymphocyte egress from PPs. Lymphocytes leave PPs via lymphatics leading to mLN. Flow cytometry of mLN-afferent intestinal lymph showed a large percentage of naive CD62L+ lymphocytes (Figure 2a, b), suggesting that cells originating from PPs and intestinal follicles account for a substantial proportion of cells in the intestinal lymph. To measure lymphocyte egress from PPs during infection, we determined cell numbers in mLN-afferent lymphatics using two-photon microscopy. Bone marrow from enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-expressing donors was grafted to irradiated recipient mice to fluorescently mark all hematopoietic cells. Bone marrow chimeras were infected for 7 days or not infected and the number or EGFP+ cells in lymphatics was determined. This approach provided a first indication that egress from infected PPs was reduced (Figure 2c). To selectively mark PP-derived cells in the intestinal lymph and other compartments, we injected fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) into PPs (Figure 2d). FITC injection marked virtually all cells in PPs (Figure 2e). One day after injection, PPs contained newly recruited non-labeled cells along with ∼25% of FITC+ cells that had remained in PPs since the injection (Figure 2f). Concomitantly, FITC+ cells were found in mLN, peripheral lymph nodes, spleen, and blood 1 day after FITC injection (Figure 2f). To confirm that these cells originated from PPs, we orally administered the S1P receptor agonist FTY72035 before FITC injection to block egress from PPs. One day after injection, the percentage of FITC+ cells in PPs of FTY720-treated control mice was still >75% and the percentage of FITC+ cells found in other organs was lower than that in untreated mice (Figure 2f). These results validate that FITC+ cells in other organs originate from PPs. To directly monitor egress from PPs, we isolated mLN-afferent lymph 1 day after FITC injection. Comparing lymph isolations from non-infected and days 5–8 infected mice, we observed a significant reduction in the percentage of FITC+—that is, PP-derived cells—among intestinal lymph cells (Figure 2g). These results provide direct evidence that infection reduces egress from PPs.

Figure 2.

Infection abrogates lymphocyte egress from Peyer's patches (PPs) into intestinal lymph. (a) Lymphocyte composition of intestinal mesenteric lymph node (mLN)-afferent lymph. Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots gated on DAPI− cells. (b) Intestinal lymph composition, mean+s.d. of 19 non-infected (d0) and 11 infected (d6–8) mice, seven independent experiments. (c) 2P-microscopic cell quantification in mLN-afferent lymphatics of non-infected (d0) or d7-infected mice. Four independent experiments, symbols represent mice. Mann–Whitney test. (d) Injection of fluorescent dye fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) to label PP cells. (e) Non-injected and injected PP 2 h after injection. Representative FACS plots gated on DAPI− cells. (f) PPs 1 day after FITC injection. FTY720 was given po before FITC injection to block egress from PPs. Four independent experiments, total 2–7 mice per group. PP panels: symbols represent individual PPs. Other organs: symbols represent individual mice. (g) Quantification of PP-derived intestinal lymph cells. Lymph was isolated 1 day after FITC injection to PPs. fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots gated on viable cells. Four independent experiments. Two experiments analyzed CD69wt/ko bone marrow chimeras, further data from which is shown in Figure 7a. Dots represent mice. ‘mLNaff'/'mLNeff', mLN-afferent/efferent lymph. Mann–Whitney test.

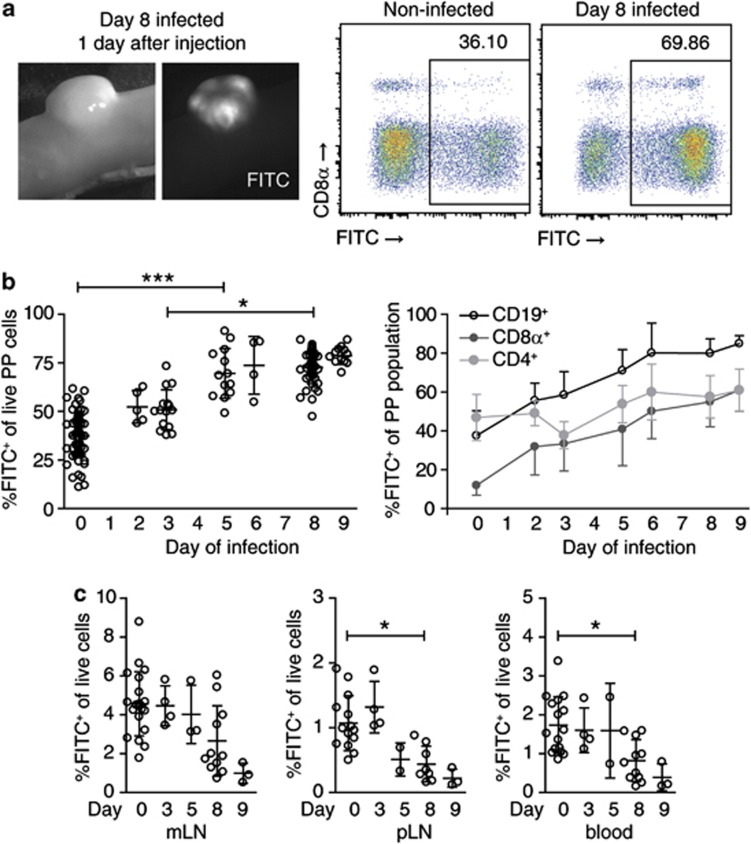

Localized Salmonella infection sequesters lymphocytes in PPs

To measure the efficiency of lymphocyte egress from infected PPs, we FITC-injected PPs on different days of Salmonella infection and analyzed them 1 day later (Figure 3a). Percentages of FITC+ cells in PPs 1 day after FITC injection steadily increased during the course of infection (Figure 3b). As lymphocyte entry into infected PPs was not increased during infection, the percentages of FITC+ cells in PPs provided a direct measure of the degree of lymphocyte retention. Infection strongly increased the retention of CD19+ and CD8α+ cells. This effect was visible when the entire population of CD19+ or CD8α+ cells was analyzed but was most prominent among the CD62L+ naive subpopulations, which account for the majority of CD19+ and CD8α+ cells in PPs (Supplementary Figure 1a, b online). Of note, the effect on CD4+ cells was less pronounced because the CD4+ cell population comprises up to 50% of CD62L− effector/memory cells—for example, follicular helper T cells—which show high retention rates even in non-infected mice (see ref. 28 and Supplementary Figure 1a, b). Nevertheless, progressively increasing percentages of FITC+ cells among CD19+ and CD8α+ cells suggested that infection induced lymphocyte retention in PPs and that the degree of retention was associated with the stage of the infection. On day 8 or day 9 of infection, we furthermore observed that dissemination of FITC+ cells into other organs was significantly reduced compared with early infection time points or non-infected mice (Figure 3c). These data indicate that all major recirculating lymphocyte populations are trapped in infected PPs.

Figure 3.

Salmonella infection causes retention of the major lymphocyte populations in Peyer's patches (PPs). (a) PPs 1 day after fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) injection. Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots gated on DAPI− cells. (b) Lymphocyte retention in hypertrophic PPs. Non-infected or Salmonella-infected PPs were FITC-injected and analyzed 1 day later. Eight independent experiments comparing non-infected mice (total 18) to d3 (4 mice), d5 (3), d6 (1), d8 (11), or d9 (3) infected mice. The indicated “day of infection” is the day of analysis. Symbols represent individual PPs. %FITC+ cells was determined among CD19+/CD4+/CD8α+ PP subpopulations. Mean+s.d. of individual PPs. Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn's multiple comparison test. (c) Dissemination of FITC-labeled, PP-derived cells into mesenteric lymph node (mLN), peripheral lymph nodes, and blood. Mean+s.d. of individual mice, see (b) for number of mice and experiments. Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn's multiple comparison test.

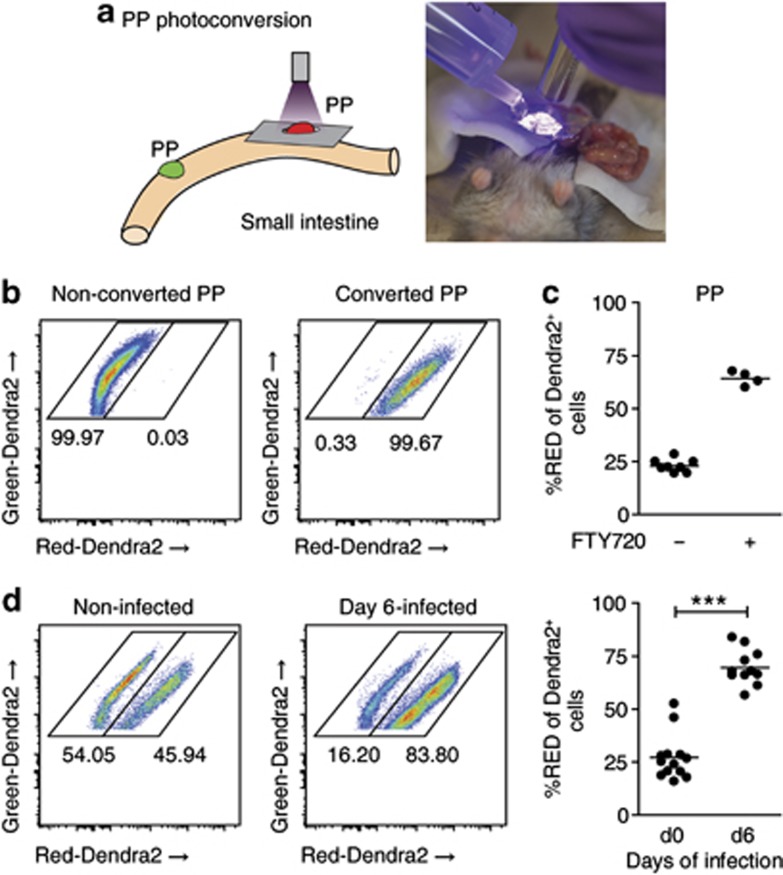

In addition to FITC injection, we used a photoconversion approach to label all cells in PPs.27, 28 To this end, we generated bone marrow chimeras expressing a histone-fusion variant of the photoconvertible fluorochrome Dendra2 (H2B-Dendra2), which changes from green to red emission upon exposure to ultraviolet/violet light. To photoconvert H2B-Dendra2-expressing lymphocytes in PPs, individual PPs were illuminated with ultraviolet/violet light for 10 s (Figure 4a). After illumination, almost all Dendra2-expressing cells in PPs emitted a Dendra2-Red signal (Figure 4b). Consistent with the FITC-injection approach, 1 day after photoconversion, percentages of Dendra2-Red cells had declined to around 25%, whereas in FTY720-treated mice, percentages remained at ∼70% (Figure 4c). We next infected H2B-Dendra2-expressing bone marrow chimeras with SL1344ΔaroA. PPs were illuminated on day 5 of infection and analyzed 1 day later. In accordance with our observations in FITC-injected PPs, Salmonella infection increased the percentage of Dendra2-Red cells in PPs 1 day after photoconversion, compared with PPs from non-infected mice (Figure 4d). Together, these experiments show that Salmonella-infected PPs establish an efficient egress blockade that affects the major lymphocyte populations in PPs.

Figure 4.

Photoconversion reveals infection-induced lymphocyte retention. (a) Illumination of Peyer's patches (PPs) to photoconvert Dendra2-expressing cells. PPs of bone marrow chimeras expressing the red-to-green photoconvertible fluorochrome Dendra2 were illuminated with ultraviolet (UV) light of 370–410 nm. (b) PP immediately after illumination. All Dendra2-expressing cells emit a Dendra2-Red signal. (c) FTY720 was given po 4 h after the photoconversion surgery to block egress from PPs. PPs were illuminated and analyzed 1 day later. Four control and two FTY720-treated mice. Symbols represent a pool of one to two PPs. (d) Infection-induced lymphocyte retention shown by photoconversion of Dendra2. Dendra2 bone marrow chimeras were not infected (d0) or infected for 5 days (d5). PPs were illuminated to convert Dendra2-Green to Dendra2-Red. Retention of Dendra2-Red cells in PPs was analyzed 1 day later. Two independent experiments, six non-infected and four infected mice; symbols represent a pool of one or two PPs. Mann–Whitney test.

Systemic administration of TLR ligands abrogates egress from PPs

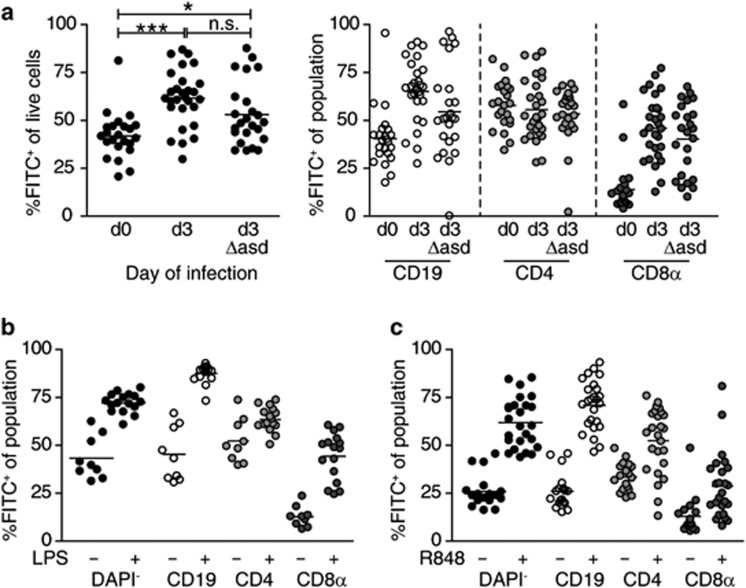

Many inflammatory stimuli reduce egress.2, 3, 9, 10, 18 We therefore tested whether the egress blockade in PPs required active pathogen replication. To this end, we injected FITC to PPs 2 days after infection with a replication-deficient Salmonella strain (SL1344ΔaroAΔasd). Mice were analyzed 1 day later, at which time point no more viable bacteria were detectable in PPs (data not shown). Lymphocyte retention in SL1344ΔaroAΔasd-infected PPs was lower compared with the same time point after infection with the replication-competent strain (SL1344ΔaroA, Figure 5a). Nevertheless, the proportion of FITC+ cells in PPs of SL1344ΔaroAΔasd-infected mice was still significantly higher than that in non-infected mice, suggesting that even in the absence of replication, bacterial invasion and the presence of bacterial components induced lymphocyte retention. Similar to the SL1344ΔaroA infection, 3-day infection with replication-deficient bacteria did not reduce dissemination of FITC+ cells from PPs to mLN compared with non-infected mice (Supplementary Figure 2a). On the basis of this finding, we tested whether the egress blockade required ongoing infection. Therefore, we injected mice intraperitoneally with 50 μg Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS) shortly after FITC injection and analyzed PPs 1 day later. Indeed, LPS injection triggered lymphocyte retention in PPs almost to the same degree as observed after FTY720 treatment or on late days of Salmonella infection (Figure 5b). A similarly strong lymphocyte retention was observed when we administered a Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7)7/8-activating imidazoquinoline compound, R848, po to mice after FITC injection (Figure 5c). Of note, within a day, these retention effects did not induce apparent PP hypertrophy (data not shown) nor did they strongly reduce the spread of FITC+ cells from PPs to other lymph nodes (Supplementary Figure 2b). Thus, ongoing infection or systemic inflammatory stimuli both induce lymphocyte retention and abrogate egress from PPs.

Figure 5.

Lymphocyte retention in Peyer's patches (PPs) after infection with replication-deficient Salmonella or systemic Toll-like receptor (TLR) stimulation. (a) Mice were not infected, infected for 2 days with SL1344ΔaroA, or infected for 2 days with replication-deficient strain SL1344ΔaroAΔasd. PPs were fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-injected and analyzed 1 day later (d0, d3, d3Δasd, respectively). Two independent experiments, total five to six mice per group. Dots represent individual PPs. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. (b) Mice were given 50 μg LPS intraperitoneally after FITC-injection. PPs were analyzed 1 day later. Two independent experiments, total two to three mice per group. Dots represent individual PPs. (c) Mice were given 10 μg R848 po after FITC injection. PPs were analyzed 1 day later. Three independent experiments, five to six mice per group. Symbols represent individual PPs. Note that data from two of the control mice are identical to data shown in Figure 2f because control mice, R848-treated mice, and FTY720-treated mice were analyzed in the same experiments.

Lymphocyte retention in infected PPs is independent of IFNAR, TNFR1, and CD69

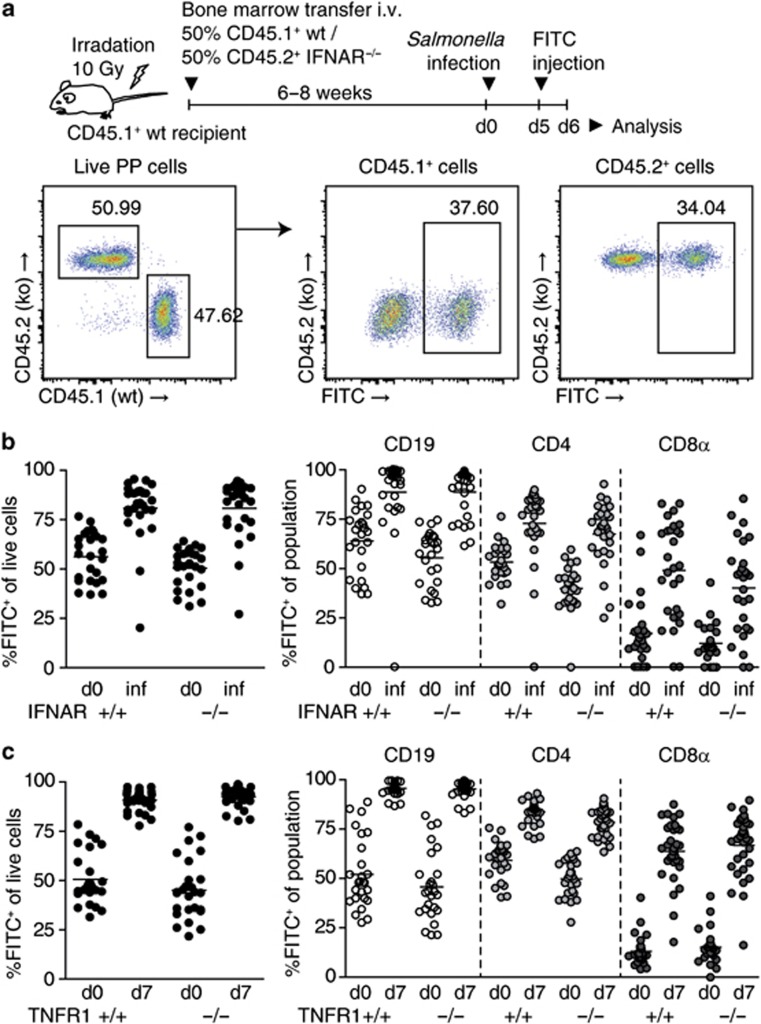

Next, we sought to elucidate the mechanism of lymphocyte retention in Salmonella-infected PPs. To test whether the IFNAR/CD69/S1PR1 axis was involved, we first addressed whether IFNAR was required on lymphocytes for their retention. To this end, we grafted an equal mix of CD45.1+ wild-type (wt) and CD45.2+IFNAR−/− (ko) bone marrow to lethally irradiated CD45.1+ wt recipients. These “IFNARwt/ko chimeras” were infected with Salmonella for 5–6 days, PPs were FITC-injected, and analyzed 1 day later (Figure 6a). Both IFNAR-proficient and IFNAR-deficient lymphocytes were efficiently retained in PPs of IFNARwt/ko chimeras (Figure 6b), indicating that IFNAR is not required on lymphocytes for their retention in infected PPs.

Figure 6.

Lymphocyte retention in Salmonella-infected Peyer's patches (PPs) is independent of type I interferon receptor (IFNAR) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α receptor 1. (a) Experimental setup to investigate effect of IFNAR deficiency on lymphocyte retention in PPs. Irradiated recipients were given bone marrow from CD45.1+ wild-type (wt) and CD45.2+ IFNAR−/− donor mice. Thus, generated mixed IFNARwt/ko chimeric mice were infected with Salmonella strain SL1344ΔaroA. PPs were fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) injected and analyzed 1 day after injection. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots show the gating strategy for analysis. The left plot is gated on viable PP cells. Corresponding setups were used to investigate the effects of TNFR1 and CD69 deficiency. (b) Lymphocyte retention in PPs of infected IFNARwt/ko chimeras. PP cells were subgated on IFNARwt and IFNARko cells and percentage of FITC+ cells was determined. IFNARwt and IFNARko cells were further subgated on CD19/CD4/CD8α and analyzed for retention. Two independent experiments, total six mice per group. Mice were analyzed on day 6 or 7 of infection (‘inf'). Symbols represent individual PPs. (c) Lymphocyte retention in PPs of infected mixed TNFR1wt/ko chimeras was investigated as described in (a) and (b). Two independent experiments, total seven to eight mice per group. Dots represent individual PPs.

Besides IFNα/β, TNF-α has been suggested to upregulate CD69 and abrogate lymphocyte egress.20 We therefore infected TNFR1wt/ko chimeras with Salmonella, FITC-injected PPs on day 6 of infection, and analyzed them 1 day later. Both TNFR1-proficient and TNFR1-deficient lymphocytes were efficiently retained in PPs, suggesting that infection-induced retention does not require TNFR1 on lymphocytes (Figure 6c). Similarly, lymphocyte retention in response to LPS was independent of TNFR1 on lymphocytes (data not shown).

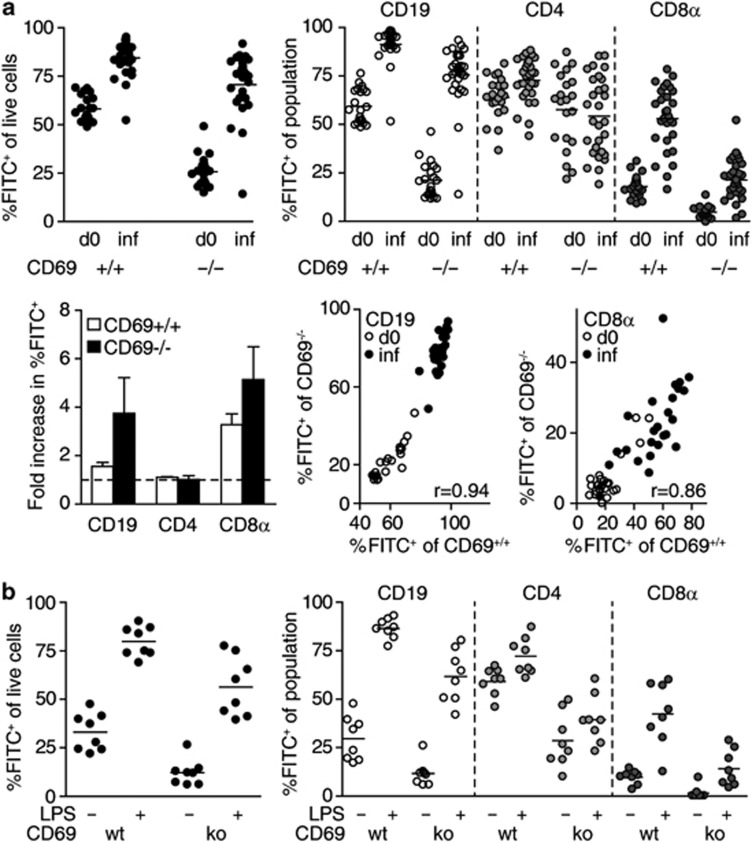

Different triggers blocking egress are thought to converge in the CD69-dependent pathway. One might therefore expect that stimuli other than IFNα/β or TNF-α could trigger CD69/S1PR1-mediated retention of recirculating lymphocytes in infected PPs. Of note, naive lymphocytes express low levels of CD69 and expression of CD69 on naive lymphocytes was not altered in infected compared with non-infected PPs (Supplementary Figure 3a, b), suggesting that naive lymphocyte retention was not because of elevated expression of CD69. To test whether CD69 was required on lymphocytes for their retention in infected PPs, we examined CD69wt/ko chimeras (Figure 7a). In non-infected CD69wt/ko chimeras, percentages of FITC+ cells among CD69-deficient PP cells were lower than those among CD69-proficient cells, suggesting that CD69-deficient lymphocytes have a lower dwell time in PPs than wt lymphocytes. Nevertheless, in infected CD69wt/ko chimeras, both CD69-proficient and CD69-deficient PP cells displayed increased percentages of FITC+ cells compared with non-infected chimeras, suggesting that both populations were efficiently retained. As observed previously, retention affected mainly CD19+ and CD8α+ lymphocytes. Retention values increased by at least the same factor for CD69-deficient and CD69-proficient lymphocytes, suggesting that the infection-induced retention mechanism overcomes the defect which CD69-deficiency imposes on homeostatic recirculation. In the same PP, there was a significant correlation between retention of CD69wt and CD69ko subpopulations, suggesting that the lymphocyte egress blockade affected both populations with the same efficiency. These results indicate that CD69 is not required on lymphocytes for their retention in PPs during Salmonella infection and that the infection-induced egress blockade relies on CD69-independent mechanisms.

Figure 7.

Lymphocyte retention after Salmonella infection or systemic LPS administration is independent of CD69. (a) Lymphocyte retention in Peyer's patches (PPs) of Salmonella-infected mixed CD69wt/ko chimeras. Mice were analyzed on days 5–7 of infection, 1 day after FITC-injection, respectively (‘inf'). Four independent experiments, total six to seven mice per group. Symbols represent individual PPs. To calculate fold increase in retention, the average percentages of fluorescein isothiocyanate positive (FITC+) cells among the indicated populations in infected PP were divided by those in non-infected PP. Dashed line indicates fold increase of 1. Mean+s.d. of three experiments. Correlation of retention values (%FITC+ of population) between indicated CD69wt and CD69ko populations in the same PP. r indicates Spearman's correlation coefficient. (b) Lymphocyte retention in PPs of LPS-treated CD69wt/ko chimeras. FITC was injected to PPs, 50 μg LPS were given intraperitoneally, and PPs were analyzed 1 day later. Viable PPs cells were subgated on CD69wt and CD69ko cells. CD69wt and CD69ko cells were further subgated on CD19/CD4/CD8α. One experiment, two mice per group. Symbols represent individual PPs.

Infection-induced shutdown requires several days to establish and could rely on complex changes in lymphocytes and lymphoid organ environment. In comparison, LPS-induced retention was relatively fast. We therefore also tested whether LPS-induced lymphocyte retention required CD69 expression. To this end, FITC was injected to PPs of CD69wt/ko chimeras and 50 μg LPS were intraperitoneally injected shortly after surgery. Analysis 1 day later showed that LPS-induced retention of CD69-deficient and CD69-proficient cells was equally efficient (Figure 7b). Consistently, we observed that adoptively transferred CD69-deficient CD19+ cells were efficiently retained in PPs after LPS injection (data not shown). Therefore, we propose that even fast “shutdown” can occur independently of CD69.

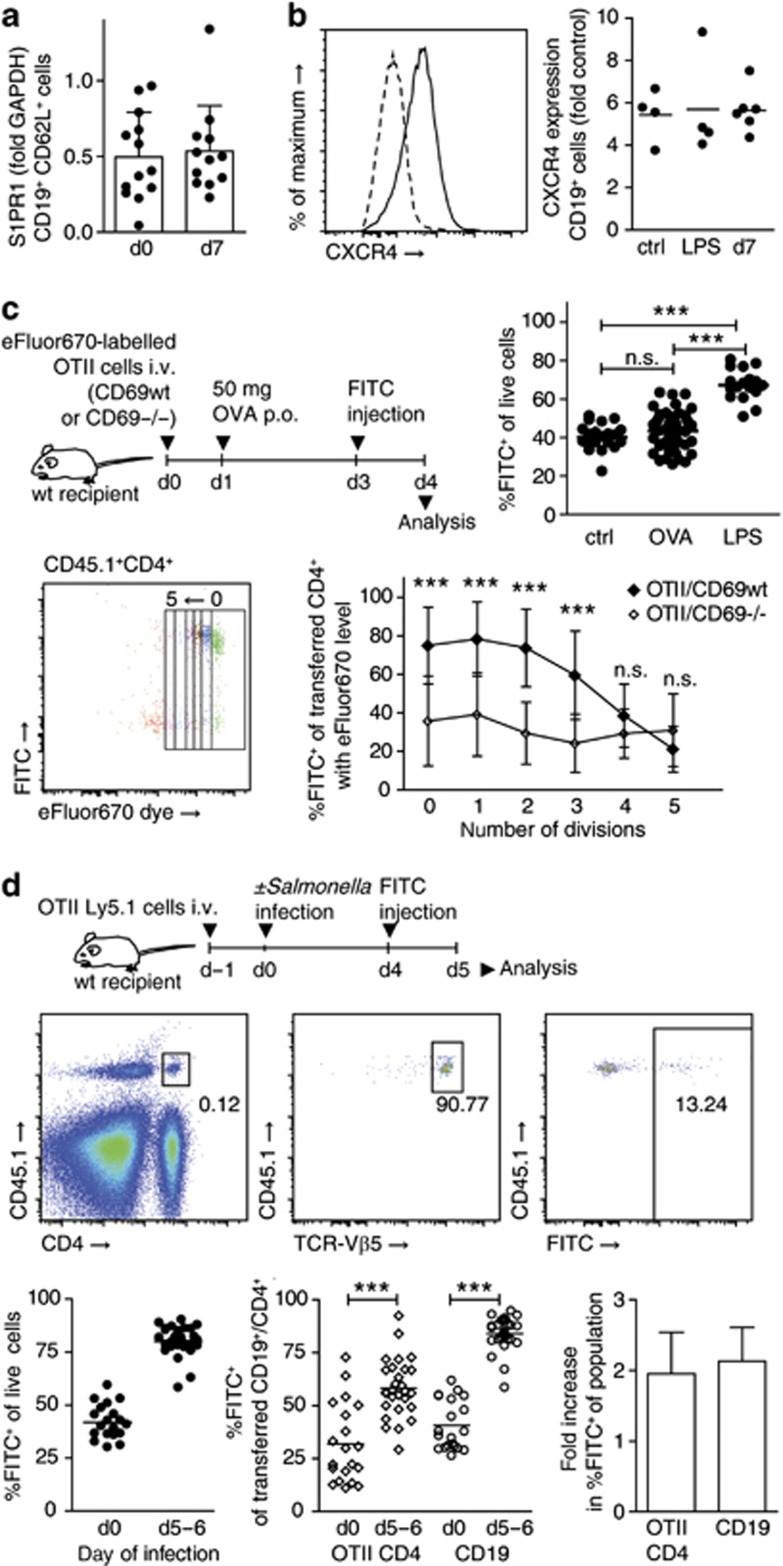

Two distinct mechanisms promote lymphocyte retention in PPs

To reconcile our findings with a proposed role for IFNα/β/CD69/S1PR1, we hypothesized that two distinct mechanisms of lymphocyte retention must exist, which differ in their requirement of CD69. CD69 has been suggested to retain lymphocytes during the first hours of lymphocyte activation before other mechanisms, such as transcriptional regulation of S1P receptors, are initiated.24 We therefore measured S1PR1 transcript levels in CD19+CD62L+ cells sorted from PPs. However, we did not observe a consistent reduction in S1PR1 transcript levels in cells from infected PPs compared with cells from non-infected PPs (Figure 8a). Recently, CXCR4 has been reported to promote B-cell egress from PPs.28 We therefore measured CXCR4 surface expression on PP cells from non-treated, LPS-treated, and day 7-infected mice. CXCR4 expression was almost exclusively found on CD19+ cells. However, expression was unaltered in lymphocytes from infected PPs compared with non-infected PPs (Figure 8b). These results suggest that infection does not retain lymphocytes through direct regulation of the lymphocyte egress factors S1PR1 and CXCR4.

Figure 8.

CD69-dependent and -independent lymphocyte retention mechanisms. (a) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) expression in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-sorted CD19+CD62L+ cells from non-infected and day 7-infected Peyer's patches (PPs). A total of 13 (d0) and 12 (d7) samples generated in eight independent sorts. For one sample, PPs were pooled from one to two mice. Mean+s.d. of samples. (b) CXCR4 expression on CD19+ cells in PPs of non-infected (ctrl), LPS-treated (LPS), and day 7-infected (d7) mice, determined using flow cytometry. Two independent experiments, total four to six mice per group. Symbols represent PP pools from individual mice. (c) Selective retention of activated CD4+ T cells. CD69wtOTII or CD69−/−OTII cells labeled with cell proliferation dye were transferred to congenic recipients. Fifty microgram OVA were given po, PPs were fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-injected on day 3 and analyzed on day 4. Symbols represent individual PPs. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Tukey post test. FACS plot from CD69wtOTII transfer shows transferred CD4+ cells. Transferred CD4+ cells were subgated on division cycles. Mean+s.d. of individual PPs. Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post test comparing genotypes. Four experiments with total 4 (no OVA), 11 (CD69wtOTII+OVA), 8 (CD69−/−OTII+OVA), and three mice per group (LPS). (d) Retention of non-activated OTII cells. OTII cells were transferred to congenic recipients. Mice were infected or not infected and analyzed on days 5–6, 1 day after FITC injection. Left FACS plot is gated on viable PP cells, subsequent plots gated on indicated subpopulations. Two experiments, total four (d0) and six (d5–6) mice. Symbols represent individual PPs. Mann–Whitney test. Fold retention infected/non-infected PPs. Mean+s.d. of experiments.

To understand which circumstances determine the mode of lymphocyte retention, we next sought to identify stimuli that sequester lymphocytes in a CD69-dependent manner. TCR-mediated antigen recognition efficiently induces CD69 expression. We therefore tested whether upon priming, CD4+ T cells would require CD69 for their retention. To this end, CD69-proficient or CD69-deficient transgenic ovalbumin (OVA)-specific OTII cells were labeled with cell proliferation dye and adoptively transferred into congenic wt recipients. OTII cells were activated by oral administration of 50 mg OVA, in the absence of adjuvant. PPs were FITC-injected 2 days later and analyzed 1 day after. Interestingly, although OTII cells in PPs of OVA-fed mice were proliferating, the percentage of FITC+ cells among all PPs cells had not increased in OVA-fed compared with control mice (Figure 8c). This suggests that antigen-specific activation of T cells per se does not necessarily shut down egress of all lymphocytes in the compartment. In contrast, percentages of FITC+ cells among proliferating CD69+/+OTII cells had increased to around 70%, indicating that activated OTII cells were selectively retained in PPs. Strikingly, percentages of FITC+ cells among CD69−/−OTII cells were significantly lower than those among CD69+/+OTII cells, suggesting that the retention of activated OTII cells was dependent on CD69. These results suggest that CD69-dependent retention mechanisms require specific activation of the lymphocyte and act via a lymphocyte-intrinsic mechanism, whereas other cells in the same compartment remain unaffected.

In contrast to this selective retention mode, infected PP shutdown retained all lymphocytes in the organ. We next tested whether this process required antigen recognition by the affected lymphocytes. To this end, we investigated whether non-activated OTII cells would be retained by Salmonella-induced shutdown. OTII cells were adoptively transferred to congenic recipients. One day later, mice were infected with Salmonella. PPs were FITC-injected on day 4 or 5 of infection and analyzed 1 day later. CD4+ OTII cell retention in infected PPs increased by about the same factor as that of transferred CD19+ cells and endogenous PP cells (Figure 8d), suggesting that CD4+ T cell retention during Salmonella infection does not require antigen recognition by the lymphocyte.

Altogether, these findings show that during infection, PPs establish a compartment-wide egress blockade that affects the major lymphocyte subsets and does not require CD69 expression on lymphocytes. In contrast, CD69 is critical to retain activated lymphocytes in PPs for several divisions by a mechanism that does not affect other cells in the compartment.

Discussion

Lymphoid organ hypertrophy is a fundamental component of the immune response to localized infection14, 15, 17 and diverse inflammatory triggers.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 In contrast, the IFNAR/CD69/S1PR1 axis has remained the only lymphocyte-intrinsic mechanism described to date that links inflammatory stimuli and lymphocyte egress.20 In this study, we describe the requirements for lymphocyte egress in a model of localized, infection-induced lymphoid organ hypertrophy and extend the current hypothesis that the IFNAR/CD69/S1PR1 axis mediates lymphoid organ shutdown during this type of immune response.11, 12, 20, 24, 25

Using in vivo photoconversion as well as fluorescent labeling of PP cells combined with analysis of the intestinal lymph, we directly monitored lymphocyte egress from intestinal PPs during infection. Our findings provide direct evidence that PP hypertrophy is the result of a compartment-wide egress blockade. With progressive infection, the efficiency of lymphocyte egress decreased. This egress blockade and resulting lymphocyte retention were the major cause of PP hypertrophy. In contrast, enhanced lymphocyte recruitment and proliferation did not decisively contribute to PP enlargement. Many studies have suggested that increased recruitment of lymphocytes is the major cause of lymphoid organ hypertrophy.4, 5, 6, 8, 14, 15, 36, 37 Although multiple inflammatory stimuli are known to temporarily abrogate egress,2, 3, 9, 10, 18 and such observations have been referenced in the context of lymphoid organ hypertrophy, egress from secondary lymphoid organs has hardly been investigated during local infection because of the inavailability of suitable methods to measure egress. In fact, increased accumulation of adoptively transferred cells during infection, interpreted as an increase in entry, might also mirror a block in egress.8, 14 Using direct readouts of lymphocyte egress and retention, we show that local infection causes a sustained egress blockade that mediates lymphoid organ hypertrophy.

Importantly, lymphocyte retention was not restricted to activated effector cells. Instead, retention affected most prominently the CD62L-expressing, naive recirculating lymphocyte populations. This process did not require antigen-specific activation, engagement of IFNAR or TNFR1, or CD69. Infection-induced lymphoid organ shutdown can thus occur independently of the CD69-dependent pathway and does not rely on sequestration of every individual lymphocyte following activation through lymphocyte-expressed IFNAR, TNFR1, or CD69. Instead, infection-induced shutdown is global—that is, it encompasses all naive, recirculating lymphocyte populations, prolongs their retention, and inhibits their exit into the lymph.

In contrast to infection-induced shutdown, retention of activated CD4+ T cells in PPs was selective to this population and was dependent on CD69. Our data thus show that CD69 is a critical mediator of TCR-triggered lymphocyte retention and answer the open question whether CD69 can function downstream of TCR to abrogate egress.24 CD69 is rapidly upregulated on newly activated CD4+ T cells, presumably causing the loss of surface S1PR1.25 S1PR1 is transcriptionally downregulated in activated CD4+ T cells19 until surface expression starts to gradually recover to the point where T cells are thought to gain capacity to leave the lymphoid organ.19, 38 In accordance with this model, we observed that activated T cells were retained in PPs for several divisions in a CD69-dependent manner. The role of CD69 in TCR-mediated retention can possibly explain the effect of CD69 deficiency on recirculation kinetics of lymphocytes in the steady state. Retention rates of CD69-deficient CD19+ and CD8α+ lymphocytes in PPs were consistently lower than those of the corresponding wt lymphocytes in the same organ. These results are in accordance with other reports proposing antigen-encounter events to be an important factor controlling lymphocyte dwell time in lymphoid organs.39, 40, 41 CD4+ T cell transit through lymph nodes is accelerated in the absence of MHCII.39 Furthermore, recognition of self-antigen as well as microbiota have been suggested to sustain CD69 expression and affect lymphoid organ transit times.40, 41 On the basis of these reports, it appears conceivable that CD69 deficiency should reduce lymphocyte dwell time in the lymphoid organs.

Our findings suggest that the mode of lymphocyte retention observed in Salmonella-infected PPs and in response to systemic TLR stimulation is distinct from the previously described CD69-mediated pathway.20 In Salmonella-infected PPs, lymphocytes were retained without specific activation through one of the previously named lymphocyte-expressed receptors. One might speculate that this mode of retention relies on changes in the lymphoid organ environment, like alterations in the availability of S1P12, 32, 42, 43 or effects on the barrier function of lymphatic endothelium.43, 44, 45 A long-standing debate concerns the distinction between such compartment-wide effects and lymphocyte-intrinsic sequestration mechanisms. Seminal findings on lymphocyte egress arose from investigation of the immunosuppressive effects of FTY720. In its phosphorylated form, FTY720 engages S1P receptors and abrogates lymphocyte egress.35 S1P receptors are present on lymphocytes as well as on non-hematopoietic cells, such as on vascular and lymphatic endothelium. Controversy still surrounds the question whether FTY720 blocks lymphocyte egress mainly through “functional antagonism”—that is, internalization and inactivation of S1PR1 on lymphocytes19, 46, 47 or rather through agonism on lymphatic endothelial S1PR1, which modulates portals in the egress barrier.35, 43, 44, 45 Broadly speaking, this discussion concerns whether major changes in lymphocyte egress are controlled on the level of the lymphocyte or the lymphoid compartment.24, 43, 48 Our findings might offer an explanation to reconcile these conflicting concepts. We propose that at least two distinct lymphocyte sequestration pathways exist, which can be individually triggered in an uncoupled manner. Antigen-specific priming selectively trapped activated T cells in PPs, demonstrating that TCR-mediated CD69 activation abrogates lymphocyte egress through a lymphocyte-intrinsic retention mechanism. In contrast, infection-induced shutdown affected all lymphocyte populations in the compartment independently of their activation status or CD69 expression. Inflammation-induced changes in the compartment could account for this effect. Still, both mechanisms could include transcriptional regulation of the egress machinery.24 Whether infection-induced shutdown interferes with S1PR1-mediated egress is open. Egress from PPs is S1PR1-dependent19 and FTY720 blocks PP egress of plasmablasts49 and naive lymphocytes (see ref. 28 and our data); therefore, it remains possible that the infection-induced egress blockade targets this critical pathway.

The two distinct retention mechanisms might serve different purposes. Lymphoid organ shutdown is commonly suggested to serve the efficient induction of adaptive immune responses by increasing the frequency of pathogen-specific naive lymphocytes and fostering lymphocyte–antigen encounters.4, 8, 11, 12, 13 This explanation entails that lymphoid organ shutdown could subside after successful lymphocyte priming. Conversely, we observed that the egress blockade continued and intensified for 9 days after infection. Moreover, our data suggest that the CD69-dependent, lymphocyte-intrinsic sequestration mechanism is sufficient to initiate the retention of activated T cells. Thus, the infection-induced and compartment-wide egress blockade might be required for reasons other than to foster lymphocyte–antigen encounters.4, 11, 12 One option might be that the two mechanisms are hierarchically organized, and infection-induced shutdown allows prolonged retention of activated effector cells compared with activation under non-inflammatory conditions. This could favor maturation of effector cells24 or the generation of specific memory. If the infection-induced egress blockade relies on physical reinforcement of the egress barrier, another purpose might be to reduce dissemination of pathogens or toxins, avert cell-bound pathogen spread,50 and provide additional protection from systemic infection.

Methods

Mice. Wt (C57BL/6N, Charles River, Sulzfeld), CD45.1+ mice (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ), TNFR1-deficient mice (B6.129-Tnfrsf1atm1Mak/J, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), Actin-EGFP mice (C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-EGFP)1Osb/J), and OTII-Ly5.1 mice (B6.Cg-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J × B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) were bred and reared in individually ventilated cages at the Central Animal Facility of Hannover Medical School. IFNAR-deficient mice (B6.129SV/EV-IFNAR1tm1Aguet/F20) were bred at Twincore, Hannover. CD69-deficient mice (B6.129P2-Cd69tm1Naka) and CD69-deficient OTII mice were bred at the Animal Research Centre (Tierforschungszentrum) of the University Clinic Ulm. All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with the German Law for the Protection of Animal Welfare (Tierschutzgesetz). Experiments were approved by the Lower saxony state office for consumer protection and food safety (Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit, LAVES).

Reagents. FITC (F2502, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was freshly diluted at 1 mg/ml in sterile phosphate-buffered saline before use. 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (B5002, Sigma-Aldrich) was given in the drinking water at a concentration of 0.8 mg/ml. On the first day of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine administration, mice were additionally given 3 mg 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine intraperitoneally. FTY720 (Fingolimod, F-4633, LC laboratories, Woburn, MA) was given po at a dose of 25 μg per mouse. Lipopolysaccharide from E. coli (LPS, L4005, Sigma-Aldrich) was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 50 μg per mouse. Imidazoquinoline compound R848 (tlrl-r848, Invivogen, San Diego, CA) was given po at a dose of 10 μg per mouse. Albumin from chicken egg white (Ova grade III, A5378, Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline and 50 mg in 200 μl were given po to every mouse.

Cell isolation, cell transfers, and flow cytometry were performed as described in Supplementary Methods.

Bacterial infection. S. enterica Serovar Typhimurium strains SL1344ΔaroA and SL1344ΔaroAΔasd were grown in LB medium with Streptomycin or LB/Streptomycin/Kanamycin supplemented with 50 μg/ml diaminopimelic acid (DAP, D1377, Sigma), respectively. Bacteria were harvested for infection during exponential growth phase and washed with LB/antibiotics and 3% NaHCO3. A total of 5–10 × 109 bacteria were given po in LB/antibiotics/NaHCO3. With the exception of experiments shown in Figure 5a, all experiments were performed with the replication-competent Salmonella strain SL1344ΔaroA.

Generation of H2B-Dendra2-expressing bone marrow chimeras. To generate the H2B-Dendra2 expression construct (MigH2BD2), Dendra2 from the pDendra2-N plasmid (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia) and IRES2-H2B from the pBOS-IRES2-H2BEGFP plasmid (kindly provided by Immo Prinz, Hannover Medical School) were cloned into the MigR1 plasmid51 in the place of IRES-EGFP through stepwise NcoI/ClaI and AgeI/XhoI digests. To generate H2B-Dendra2-containing virus, the resulting MigH2BD2 together with pCL-Eco was transfected into HEK-293T cells. Virus-containing supernatant was harvested on the three following days. To enrich bone marrow precursor cells, bone marrow was incubated with rat IgG antibodies to CD11b, CD8β, CD49b, CD4, Gr-1, B220, CD11c, and CD19. Cells were then incubated with sheep anti-rat IgG Dynabeads (Invitrogen), and the labeled cell populations were depleted using magnetic separation. Enriched bone marrow precursor cells were cultured with IL-7, IL-6, SCF, and Flt3L for 4 days and infected with H2B-Dendra2-expressing virus on days 2 and 4 using spin infection. On day 5, cells were harvested and 106 cells were transferred intraventrally to irradiated recipients.

Bone marrow chimeras. Recipient mice were irradiated at 10 Gy. For mixed chimeras, donor bone marrow from WT and IFNAR/TNFR1/CD69-deficient mice was mixed at a 1:1 ratio. For mixed chimeras and EGFP chimeras, 107 cells were transferred intraventrally via the tail vein. For Dendra2-H2B chimeras, Dendra2-H2B-transduced enriched bone marrow precursor cells were harvested and 106 cells were transferred intraventrally All bone marrow recipients were given antibiotics in the drinking water for 2 weeks after irradiation (Cotrimoxazol, Ratiopharm, Ulm, Germany). Mice were analyzed after 6 weeks or later.

Two-photon microscopy of lymphatics. Two-photon microscopy of lymphatics was performed as described.52 Briefly, 200 μl olive oil were given po 1 h before analysis and TRITC-labeled dextrane was injected intraventrally 20 min before analysis. At the time point of analysis, mice were anaesthetized, lymphatics were ligated close to the mLN, and the mice were killed by cervical dislocation. An explant containing a piece of the small intestine, the mLN, and the connecting lymph and blood vessel bundles was glued into a petri dish and analyzed under the microscope.

FITC injection and photoconversion surgery. Mice were anaesthetized using ketamine and xylazine. The peritoneal cavity was opened through a small midline incision into the skin and the abdominal wall. The small intestine was exposed and FITC (1 mg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline) was injected to the first five PPs starting from the cecum. Every follicle was injected individually, using a fine glass capillary mounted to the needle holder of a micro-injector (Harvard Apparatus). For photoconversion, PPs were exposed for 10 s at a low intensity to ultraviolet/Violet light of wavelength 370–410 nm from a BlueWave 75 light curing system (Dymax, CT) equipped with a 390/40 band pass filter. During illumination, tissue surrounding the PPs was covered with aluminum foil to avoid unwanted photoconversion. Four to five PPs were photoconverted per mouse and their position was mapped for analysis.

Real-time PCR. Quantitative real-time PCR of S1PR1 expression on complementary DNA from fluorescence-activated cell sorting-sorted CD19+CD62L+DAPI− cells was carried out as described in Supplementary Methods.

Statistics. Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism. Unless indicated otherwise, plots show data pooled from several independent experiments. Number of mice, PPs, and independent experiments are given in the Figure legends. In dotplots, horizontal lines indicate the mean and one dot represents an individual PP or an individual mouse, as indicated. Bar graphs indicate mean+s.d. Statistical differences between two groups were determined using the Mann–Whitney test. Three or more groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis tests. If the overall P-value was <0.05, multiple comparison tests were performed. P-values for pairwise comparisons are indicated as follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, nonsignificant (n.s.) P>0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dirk Bumann for the Salmonella strains, and Allan Mowat, Cornelia Lindner, and Stephan Halle for comments on the manuscript. IFNAR-deficient mice were kindly provided by Ulrich Kalinke, Twincore Hannover, Germany. We acknowledge the assistance of the Cell Sorting Core Facility of Hannover Medical School. M. Ugur is supported by a scholarship from the Hannover Biomedical Research School (HBRS). This work was supported by the German Research Foundation as part of the Trilateral Chinese–Finnish–German Immunology Initiative (DFG PA921/3-1, to O.P.).

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/mi

Supplementary Material

References

- Gresser I., Guy-Grand D., Maury C., Maunoury M.T. Interferon induces peripheral lymphadenopathy in mice. J. Immunol. 1981;127:1569–1575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A.J., Seabrook T.J., Marston W.L., Dudler L., Hay J.B. A role for lymphatic endothelium in the sequestration of recirculating gamma delta T cells in TNF-alpha-stimulated lymph nodes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:327–334. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200001)30:1<327::AID-IMMU327>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee J.L., Greenwood D.L., Han X., Scheerlinck J.P. Inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-alpha regulate lymphocyte trafficking through the local lymph node. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2011;144:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunder C.A., St, John A.L., Li G., Leong K.W., Berwin B., Staats H.F., et al. Mast cell-derived particles deliver peripheral signals to remote lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:2455–2467. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan J.B., Hart J.P., Pizzo S.V., Shelburne C.P., Staats H.F., Gunn M.D., et al. Mast cell-derived tumor necrosis factor induces hypertrophy of draining lymph nodes during infection. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:1199–1205. doi: 10.1038/ni1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MartIn-Fontecha A., Sebastiani S., Hopken U.E., Uguccioni M., Lipp M., Lanzavecchia A., et al. Regulation of dendritic cell migration to the draining lymph node: impact on T lymphocyte traffic and priming. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:615–621. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawdat D.M., Rowden G., Marshall J.S. Mast cells have a pivotal role in TNF-independent lymph node hypertrophy and the mobilization of Langerhans cells in response to bacterial peptidoglycan. J. Immunol. 2006;177:1755–1762. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M., Yang Y., Wang Y., Wang Z., Fu Y.X. LIGHT regulates inflamed draining lymph node hypertrophy. J. Immunol. 2011;186:7156–7163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins J., McConnell I., Pearson J.D. Lymphocyte traffic through antigen-stimulated lymph nodes. II. Role of Prostaglandin E2 as a mediator of cell shutdown. Immunology. 1981;42:225–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell I., Hopkins J. Lymphocyte traffic through antigen-stimulated lymph nodes. I. Complement activation within lymph nodes initiates cell shutdown. Immunology. 1981;42:217–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard J.P., Moussion C., Forster R. HEVs lymphatics and homeostatic immune cell trafficking in lymph nodes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:762–773. doi: 10.1038/nri3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyster J.G. Chemokines, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:127–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J.H., Nomura N., Koprak S.L., Quackenbush E.J., Forrest M.J., Rosen H. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonism impairs the efficiency of the local immune response by altering trafficking of naive and antigen-activated CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2003;170:3662–3670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho L.P., Petritus P.M., Trochtenberg A.L., Zaph C., Hill D.A., Artis D., et al. Lymph node hypertrophy following Leishmania major infection is dependent on TLR9. J. Immunol. 2012;188:1394–1401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeure C.E., Brahimi K., Hacini F., Marchand F., Peronet R., Huerre M., et al. Anopheles mosquito bites activate cutaneous mast cells leading to a local inflammatory response and lymph node hyperplasia. J. Immunol. 2005;174:3932–3940. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lax S., Hardie D.L., Wilson A., Douglas M.R., Anderson G., Huso D., et al. The pericyte and stromal cell marker CD248 (endosialin) is required for efficient lymph node expansion. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010;40:1884–1889. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz S., Oberle K., Sander A., Bogdan C., Schleicher U. Lymphadenopathy in a novel mouse model of Bartonella-induced cat scratch disease results from lymphocyte immigration and proliferation and is regulated by interferon-alpha/beta. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;172:1005–1018. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J.G., Morris B. The immediate effect of antigens on the cell output of a lymph node. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1965;46:450–454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloubian M., Lo C.G., Cinamon G., Lesneski M.J., Xu Y., Brinkmann V., et al. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiow L.R., Rosen D.B., Brdickova N., Xu Y., An J., Lanier L.L., et al. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-alpha/beta to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature. 2006;440:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature04606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis E., Junt T., Waibler Z., Forster R., Kalinke U. Type I interferons directly regulate lymphocyte recirculation and cause transient blood lymphopenia. Blood. 2006;108:3253–3261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankovich A.J., Shiow L.R., Cyster J.G. CD69 suppresses sphingosine 1-phosophate receptor-1 (S1P1) function through interaction with membrane helix 4. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:22328–22337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Cabrera M., Munoz E., Blazquez M.V., Ursa M.A., Santis A.G., Sanchez-Madrid F. Transcriptional regulation of the gene encoding the human C-type lectin leukocyte receptor AIM/CD69 and functional characterization of its tumor necrosis factor-alpha-responsive elements. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:21545–21551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyster J.G., Schwab S.R. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:69–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel S., Milstien S. The outs and the ins of sphingosine-1-phosphate in immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:403–415. doi: 10.1038/nri2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab S.R., Cyster J.G. Finding a way out: lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1295–1301. doi: 10.1038/ni1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomura M., Yoshida N., Tanaka J., Karasawa S., Miwa Y., Miyawaki A., et al. Monitoring cellular movement in vivo with photoconvertible fluorescence protein ‘Kaede' transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:10871–10876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802278105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T.H., Bannard O., Gray E.E., Cyster J.G. CXCR4 promotes B cell egress from Peyer's patches. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:1099–1107. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mionnet C., Sanos S.L., Mondor I., Jorquera A., Laugier J.P., Germain R.N., et al. High endothelial venules as traffic control points maintaining lymphocyte population homeostasis in lymph nodes. Blood. 2011;118:6115–6122. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-367409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorova I.L., Panteleev M., Cyster J.G. Lymph node cortical sinus organization and relationship to lymphocyte egress dynamics and antigen exposure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:20447–20452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009968107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunzer M., Riemann H., Basoglu Y., Hillmer A., Weishaupt C., Balkow S., et al. Systemic administration of a TLR7 ligand leads to transient immune incompetence due to peripheral-blood leukocyte depletion. Blood. 2005;106:2424–2432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H., Sanna G., Alfonso C. Egress: a receptor-regulated step in lymphocyte trafficking. Immunol. Rev. 2003;195:160–177. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voedisch S., Koenecke C., David S., Herbrand H., Forster R., Rhen M., et al. Mesenteric lymph nodes confine dendritic cell-mediated dissemination of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and limit systemic disease in mice. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:3170–3180. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00272-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C., Hwang I.Y., Sinha R.K., Kamenyeva O., Davis M.D., Kehrl J.H. Lymph node B lymphocyte trafficking is constrained by anatomy and highly dependent upon chemoattractant desensitization. Blood. 2012;119:978–989. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-364273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandala S., Hajdu R., Bergstrom J., Quackenbush E., Xie J., Milligan J., et al. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science. 2002;296:346–349. doi: 10.1126/science.1070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg K.A., Payne G.W., Sato A., Medzhitov R., Segal S.S., Iwasaki A. Innate control of adaptive immunity via remodeling of lymph node feed arteriole. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16315–16320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506190102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto Y., Mattei L.M., Sellers S., Payne G.W., Iwasaki A. CD4+ T cells support cytotoxic T lymphocyte priming by controlling lymph node input. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:8749–8754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100567108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham T.H., Okada T., Matloubian M., Lo C.G., Cyster J.G. S1P1 receptor signaling overrides retention mediated by G alpha i-coupled receptors to promote T cell egress. Immunity. 2008;28:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandl J.N., Liou R., Klauschen F., Vrisekoop N., Monteiro J.P., Yates A.J., et al. Quantification of lymph node transit times reveals differences in antigen surveillance strategies of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;109:18036–18041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211717109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomura M., Itoh K., Kanagawa O. Naive CD4+ T lymphocytes circulate through lymphoid organs to interact with endogenous antigens and upregulate their function. J. Immunol. 2010;184:4646–4653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic K., Manta C., Rossini V., Holzmann K., Kestler H.A., Wegenka U.M., et al. CD69 regulates type I IFN-induced tolerogenic signals to mucosal CD4 T cells that attenuate their colitogenic potential. J. Immunol. 2012;188:2001–2013. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab S.R., Pereira J.P., Matloubian M., Xu Y., Huang Y., Cyster J.G. Lymphocyte sequestration through S1P lyase inhibition and disruption of S1P gradients. Science. 2005;309:1735–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1113640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H., Sanna M.G., Cahalan S.M., Gonzalez-Cabrera P.J. Tipping the gatekeeper: S1P regulation of endothelial barrier function. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S.H., Rosen H., Matheu M.P., Sanna M.G., Wang S.K., Jo E., et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate type 1 receptor agonism inhibits transendothelial migration of medullary T cells to lymphatic sinuses. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1228–1235. doi: 10.1038/ni1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna M.G., Wang S.K., Gonzalez-Cabrera P.J., Don A., Marsolais D., Matheu M.P., et al. Enhancement of capillary leakage and restoration of lymphocyte egress by a chiral S1P1 antagonist in vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:434–441. doi: 10.1038/nchembio804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allende M.L., Dreier J.L., Mandala S., Proia R.L. Expression of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor, S1P1, on T-cells controls thymic emigration. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:15396–15401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappu R., Schwab S.R., Cornelissen I., Pereira J.P., Regard J.B., Xu Y., et al. Promotion of lymphocyte egress into blood and lymph by distinct sources of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Science. 2007;316:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.1139221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.D., Kehrl J.H. The influence of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor signaling on lymphocyte trafficking: how a bioactive lipid mediator grew up from an ‘immature' vascular maturation factor to a ‘mature' mediator of lymphocyte behavior and function. Immunol. Res. 2009;43:187–197. doi: 10.1007/s12026-008-8066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohda M., Kunisawa J., Miura F., Kagiyama Y., Kurashima Y., Higuchi M., et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate regulates the egress of IgA plasmablasts from Peyer's patches for intestinal IgA responses. J. Immunol. 2008;180:5335–5343. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok S.W., Proia R.L., Brinkmann V., Mabbott N.A. B cell-specific S1PR1 deficiency blocks prion dissemination between secondary lymphoid organs. J. Immunol. 2012;188:5032–5040. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pear W.S., Miller J.P., Xu L., Pui J.C., Soffer B., Quackenbush R.C., et al. Efficient and rapid induction of a chronic myelogenous leukemia-like myeloproliferative disease in mice receiving P210 bcr/abl-transduced bone marrow. Blood. 1998;92:3780–3792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz O., Jaensson E., Persson E.K., Liu X., Worbs T., Agace W.W., et al. Intestinal CD103+, but not CX3CR1+, antigen sampling cells migrate in lymph and serve classical dendritic cell functions. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:3101–3114. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.