Abstract

Response properties of primary auditory cortical neurons in the adult common marmoset monkey (Callithrix jacchus) were modified by extensive exposure to altered vocalizations that were self-generated and rehearsed frequently. A laryngeal apparatus modification procedure permanently lowered the frequency content of the native twitter call, a complex communication vocalization consisting of a series of frequency modulation (FM) sweeps. Monkeys vocalized shortly after this procedure and maintained voicing efforts until physiological evaluation 5-15 months later. The altered twitter calls improved over time, with FM sweeps approaching but never reaching the normal spectral range. Neurons with characteristic frequencies <4.3 kHz that had been weakly activated by native twitter calls were recruited to encode self-uttered altered twitter vocalizations. These neurons showed a decrease in response magnitude and an increase in temporal dispersion of response timing to twitter call and parametric FM stimuli but a normal response profile to pure tone stimuli. Tonotopic maps in voice-modified monkeys were not distorted. These findings suggest a previously unrecognized form of cortical plasticity that is specific to higher-order processes involved in the discrimination of more complex sounds, such as species-specific vocalizations.

Keywords: auditory cortex, plasticity, primate, vocalization, learning, twitter call

Introduction

The production of communication sounds in humans and animals is subject to extensive sensorimotor interactions. The songbird system (McCasland, 1987; Doupe and Kuhl, 1999) is the principal contemporary animal model for physiological studies of sensorimotor dynamics in neural circuits of communication, and it has provided enormous insights into the substrates for such signals. However, with regard to primate vocalizations, no analogous model exists. Given the complexity and lability of primate vocalizations, this may be a more appropriate model for speech and human communication, a consideration that is the basis for the present study.

The dynamic remodeling of cortical neuron receptive field properties constitutes one form of plasticity and is seen after peripheral hearing loss (Robertson and Irvine, 1989; Rajan, 2001), classical conditioning (Weinberger, 1998), operant learning (Recanzone et al., 1993; Weinberger, 1995; Blake et al., 2002), and exposure to changes in environmental sound statistics in adult and developing animals (Weinberger, 1995; Kilgard and Merzenich, 1998a; Bao et al., 2001; Kilgard et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2001, 2002). Increased behavioral relevance of specific sound attributes can refine and expand the representation of certain receptive field properties (Recanzone et al., 1993; Buonomano and Merzenich, 1998; Weinberger, 1998; Dimyan and Weinberger, 1999; Blake et al., 2002).

In contrast, other training strategies and associative learning can degrade receptive field properties, decreasing response strength (Wiesel and Hubel, 1965; Weinberger, 1998; Blake et al., 2002), selectivity (Mioche and Singer, 1989; Crair et al., 1998), and temporal precision (Kilgard et al., 2001). In the songbird system, bilateral denervation of the syrinx affected at least two of the anterior forebrain nuclei (Solis and Doupe, 1999, 2000; Solis et al., 2000), with reduced responsiveness and selectivity to the bird's own song in LMAN (lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior neostriatum) and Area X, nuclei with mixed sensory and motor properties, and are involved in song learning and maintenance.

Although vocal production and brain lesion studies in the songbird anterior forebrain pathway has helped to dissect mechanisms of adaptive change in a higher-order cortical nuclei-basal ganglia circuit (for review, see Brainard and Doupe, 2000a), there is virtually no information on the impact of altered vocal production on the primary auditory cortex (AI). An attractive animal model is the highly vocal common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). This New World monkey vocalizes the twitter call, which consists of a series of frequency modulated (FM) sweeps or phrases. The spectral content and temporal relationship of the first and last phrase to its successor and predecessor phrase, respectively, is variable, whereas the intervening middle phrases are rather stereotyped for an individual monkey (see Fig. 1). Vocal reception studies of normal and acoustically degraded twitter calls in AI (Wang et al., 1995; Nagarajan et al., 2002) have shown a high degree of responsiveness and distributed spectral and temporal representation. In this study, an altered hearing environment was created by permanently changing the vocal production apparati in marmosets. Extracellular multiunit recordings were performed in AI of voice-modified monkeys to evaluate consequences of altered vocal production on neuronal receptive field properties for pure tone, twitter call vocalization, and parametric FM sweep stimuli.

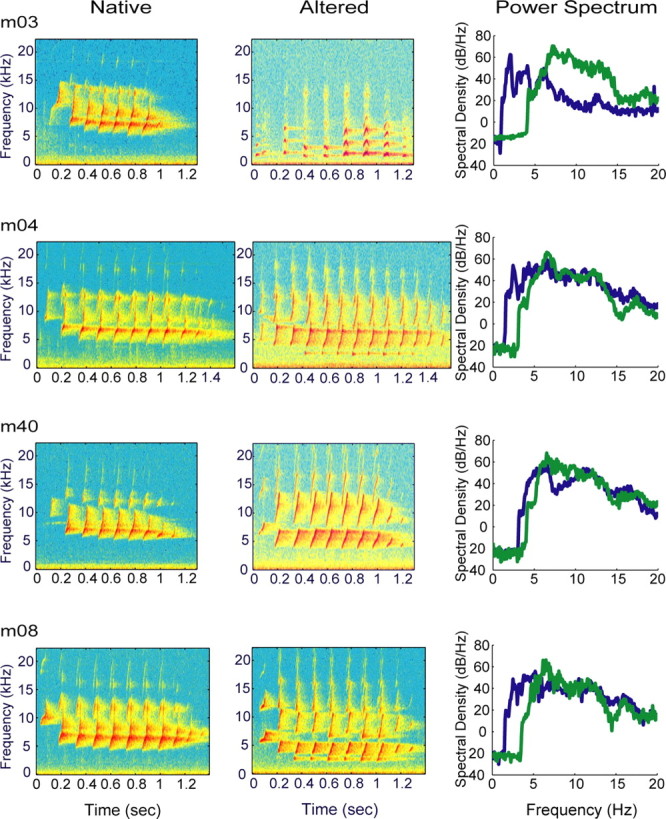

Figure 1.

Twitter call spectrograms and power spectrum plots for experimental monkeys. The marmoset twitter call consists of a series of FM sweeps or phrases. The first and last phrases differ in frequency content and interphrase interval relative to the middle phrases, which are relatively stereotyped. Native, Normal twitter calls before vocal tract modification procedure. There is little acoustic energy <4.3 kHz, which accounts for poor activation of neurons with CF <4.3 kHz. Altered, Stable twitter calls after vocal apparatus modification. The minimum frequency content is decreased by ∼1 octave. Power spectrum, In three of four cases, the spectral envelope is similar for both types of twitter calls with in individual monkeys. In all monkeys, the altered calls are shifted to lower frequencies.

Materials and Methods

Surgical preparation

Experiments were conducted on nine young adult common marmoset monkeys (2-3 years old), in accordance with an approved institutional protocol and congruent with applicable international, national, state, and institutional welfare guidelines at the University of California, San Francisco. Four monkeys served as normal controls. Of these, two monkeys underwent a focused study of low-frequency neurons for direct comparisons with the experimental group. The remaining two normal monkeys were mapped broadly throughout AI with a reduced stimulus set that did not include vocalizations or parametric FM sweeps for reconstructing full tonotopic maps. Five monkeys underwent vocal tract modification and mapping procedures. One served as a pilot (m76), and the remaining four were in the experimental group. Recordings of native vocalizations were collected from monkeys before voice modification procedures, which were performed under general anesthesia.

Monkeys were anesthetized with an isoflurane/nitrous oxide/oxygen mixture to reach a surgical plane of anesthesia. The vocal tract was modified by interrupting a unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve combined with excising bilateral cricothyroid muscles and a unilateral thyrohyoid and sternothyroid muscle complex. Perioperative analgesics were given.

Altered twitter calls voiced by experimental monkeys were recorded for several months in the convalescent period. Experimental monkeys were housed together as a colony separate from other marmoset monkeys on the same floor of the facility. Although there was no direct visual contact among experimental monkeys with other marmoset monkeys, occasional communicative exchanges were heard by observers during the simultaneous opening of two doors that separated the colonies. Monkeys in the control group were separated from the experimental group by a third door, which further minimized their exposure to altered vocalizations. Cortical recordings were performed 24-65 weeks after vocal tract modification procedures. For all brain mapping experiments, monkeys were anesthetized with an inhalational mixture of isoflurane/nitrous oxide/oxygen (2%:48%:50%) to reach a surgical plane. Skin overlying the trachea, stereotaxic pin sites, and scalp was injected with 2% lidocaine. A tracheotomy was performed to secure the airway, and intravenous access was established in the saphenous vein. Subsequently, inhalational agents were discontinued, and intravenous sodium pentobarbital (15-30 mg/kg) was administered and titrated to effect for the duration of the experiment. Normal saline with 1.5% dextrose and 20 mEq of KCl delivered at 5-8 ml/kg/h supported cardiovascular function. Ceftizoxime (10-20 mg/kg every 12 h, i.v.), a cephalosporin antibiotic that crosses the blood-brain barrier, was given for prophylaxis against infection. The core temperature was monitored with a thermistor probe and maintained at ∼38°C with a feedback controlled water blanket. The electrocardiogram and respiratory rate were monitored continuously.

The head was stabilized with a fixation device that permitted the external auditory meati to remain patent. A scalp incision followed by soft tissue mobilization exposed the temporoparietal cranium. Burr holes over the auditory forebrain were positioned extradurally, and a bone plate was removed. The dura was reflected to expose AI ventral to the lateral sulcus. The brain was kept moist under a layer of viscous silicone oil. A magnified video image of the recording zone was captured with a camera and stored in a microcomputer for labeling penetrations relative to cortical vessels. At the termination of each study, the animal was killed with an overdose of intravenous pentobarbital, followed by bilateral thoracotomies.

Stimulus generation

Experiments were performed in a double-walled sound attenuating chamber (IAC, Bronx, NY). Auditory stimuli were delivered through a STAX-54 headphone enclosed in a small chamber that was connected via a sealed tube into the external acoustic meatus of the contralateral ear [Sokolich G (1981), U.S. Patent 4251686]. The sound delivery system was calibrated with a sound meter (Brüel and Kjær 2209; Brüel and Kjær, Norcross, GA) and waveform analyzer (General Radio 1521-B; General Radio Company, West Concord, MA). The frequency response of the system was essentially flat (within 6 dB) up to 14 kHz. Above 14 kHz, the output rolled off at a rate of 10 dB/octave.

Tone bursts (3 ms linear rise and fall; total duration, 50 ms; interstimulus interval, 400-1000 ms) were generated by a microprocessor [TMS32010; 16-bit analog-to-digital (A/D) converter at 120 kHz; Texas Instruments, Dallas, TX]. Frequency-intensity response areas were recorded by presenting 675 pseudorandomized tone bursts of different frequency and sound pressure level (SPL) combinations. The entire matrix of frequency-intensity pairs covered an intensity range from 2.5 to 77.5 dB SPL in 5 dB steps and 45 frequencies in logarithmic steps that spanned 2-4 octaves centered on the estimated characteristic frequency (CF) of the neuron. A single tone burst was presented at each frequency-intensity combination (Schreiner and Mendelson, 1990).

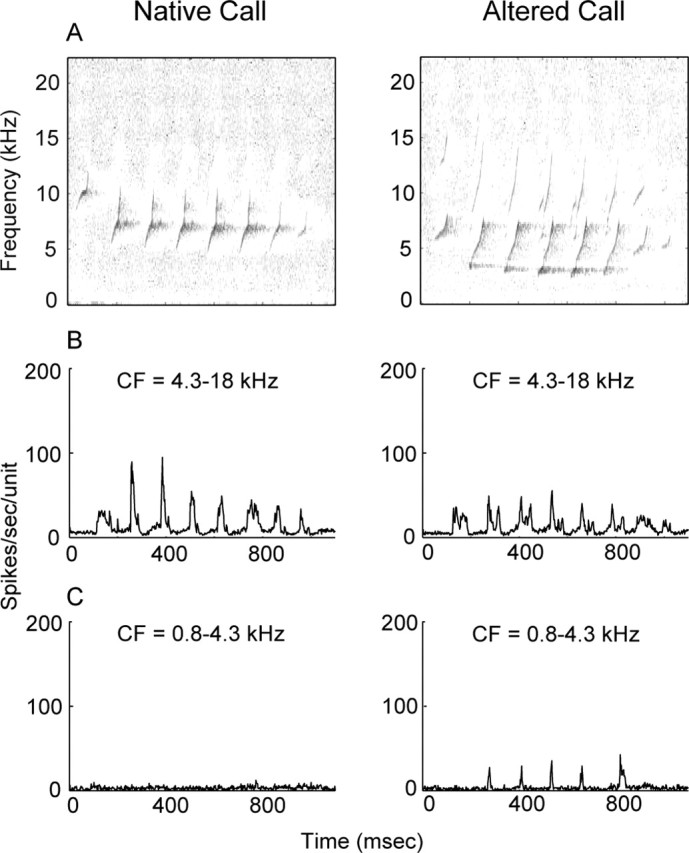

For stimulus delivery of native and altered twitter calls in Figure 1, these vocalizations were high-pass filtered to remove low-frequency background noises. Higher-order linear phase finite impulse response filters were applied to the vocal recordings. The filter pass-band (native calls range, 3.03-4.11 kHz; altered calls range, 0.97-3.03 kHz) was extended below the lowest value of the vocalization fundamental frequency and set individually for each recording. The intensity level for all vocalizations was set to 52 ± 2 dBA SPL. For the mapping experiment on m76, the complex sound stimulus set included the monkey's own native and altered vocalizations (see Fig. 5) but not parametric FM sweeps. For the experimental (m03, m04, m40, and m08) and control (m55 and m66) groups, native and altered twitter calls from all four voice-modified monkeys (Table 1) and parametric FM sweeps were used as stimuli.

Figure 5.

Population PSTH response profiles for monkey m76 to its own native and altered twitter calls. Above 5 kHz, the power spectra of the vocalizations are well matched (data not shown). The mapping procedure sampled 154 units with CF that ranges from 0.8 to 18 kHz. The data are partitioned at a CF of 4.3 kHz to assess the magnitude of evoked activity for neurons above and below this value. A, The native call does not have spectral energy <5 kHz, whereas the altered call shows energy down to 2.5 kHz. B, For neurons with CF >4.3 kHz, both native and altered calls evoke discernible spike activity. C, For neurons with CF <4.3 kHz, only the altered call results in phase-locked spike activity to call phrases. The altered call activates neurons that normally do not participate in the encoding of the native twitter call. Neurons with CF <4.3 kHz are apparently engaged in new learning of a complex communication call and are the focus of subsequent mapping experiments in voice-modified monkeys.

Table 1.

Vocalization stimuli

|

|

m03 |

m04 |

m40 |

m08 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monkey |

Nat |

Alt |

Nat |

Alt |

Nat |

Alt |

Nat |

Alt |

||||

| m03 |

• |

• |

|

• |

|

|

|

• |

||||

| m04 |

|

• |

• |

• |

|

|

|

• |

||||

| m40 |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

||||

| m08 |

|

• |

|

• |

|

|

• |

• |

||||

| m55a

|

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

||||

| m66a

|

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

• |

||||

Nat, Native; Alt, altered; •, stimulus presented.

Control monkeys.

Synthetic FM sweeps were presented at parametric rates 10-80 octaves/s in 10 octaves/s increments from 1 to 15 kHz. The envelope shape was constructed with a sinusoidal rise and fall (5 ms) with constant 1 and 15 kHz carriers within the gated period, respectively, and constant amplitude for the FM sweep duration. The frequency progression in the constant amplitude segment of FM sweeps was logarithmic. The intensity level was 52 ± 1 dBA SPL. Frequency modulation sweeps and vocalizations were presented in interleaved pseudorandomized order once every 2 s, jittered by 500 ms. There were 20 repetitions for each stimulus condition.

Recording procedure

The pilot cortical mapping effort in m76 included both hemispheres (left, 110 units; right, 44 units) and sampled across a broad CF range (0.8-18 kHz) to identify the sector within AI most changed by self-generated, altered vocalizations. Preliminary data from m76 indicated that the most pronounced plasticity effects were expressed in lower-frequency neurons. With this, neurons with CF approximately ≤4.3 kHz became the target of mapping studies in the experimental group. Monkey m76 was excluded from subsequent experimental group analysis because vocalization stimuli used in this monkey were not repeated in any other study monkey, so comprehensive comparisons could not be made.

For the experimental and control groups, cortical mapping procedures were designed to maximize data collection on low-frequency neurons. The right and left hemispheres were mapped in three of four experimental monkeys. Monkey m40 data collection was limited to the left hemisphere (LH). Broad CF sampling was also performed in two control monkeys (m59L, 80 units; m1669R, 68 units) to reconstruct tonotopic maps for comparison with m76 to assess for AI frequency map distortion. The right hemisphere (RH) was mapped in m55R and m66R control monkeys.

Neurons with CF <4.3 kHz became the primary focus of the study, because spectrally downward shifted altered vocalizations activated lower CF neurons that would otherwise only be weakly engaged by native twitter calls. Because of variations in the details of AI topography across monkeys, mapping was guided by functional (CF), not anatomical (spatial), criteria. Typically, fine grain sampling of neurons within a single hemisphere for 1.4 kHz < CF < 4.3 kHz was performed until the nonresponsive cortex or intervening blood vessels or higher CF units were encountered. Neurons that were nonresponsive and fell outside the main sampled mass or had CF >4.3 kHz were not included in the data set (post hoc). For these multiunit recordings, parylene-coated tungsten microelectrodes (Microprobe, Gaithersburg, MD) with 1-2 MΩ impedance at 1 kHz were introduced perpendicular to the surface of the cortex with a hydraulic microdrive (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) to a depth range of 650-850 μm, corresponding to layers IIIb and IV in AI. On occasion, dimpling of the cortical surface was eliminated by first advancing the electrode to a greater depth, followed by retraction to the desired depth. Action potentials from single and multiunit responses were isolated from background noise by using an on-line window discriminator (DIS-1; BAK, Mount Airy, MD). The number of discriminated spikes and times of arrival that occurred within 50 ms of tone burst and 1750-2000 ms of vocalization and FM onsets were recorded for off-line analysis. A summary of the number of cortical locations for each stimulus condition for experimental and control monkeys is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of cortical locations for different stimuli

|

Monkey |

Frequency tuning curve |

Vocalizations |

FM sweeps |

|---|---|---|---|

| m03 | 103 | 102 | 102 |

| m04 | 82 | 78 | 78 |

| m40 | 91 | 91 | 91 |

| m08 | 55 | 55 | 55 |

| m55a | 40 | 38 | 40 |

| m66a

|

31 |

29 |

31 |

Control monkeys.

Data analysis

Vocal production

Native and altered marmoset twitter calls (Fig. 1) were recorded in a manner similar to published methods (Wang et al., 1995). Vocalizations were captured with a 16-bit A/D digital tape recorder at a 48 kHz sampling rate. Twitter calls were screened and segmented using the SIGNAL/RTS system (Engineering Design, Berkeley, CA). The vocalizations were transferred to a DEC Alpha workstation for processing in the MATLAB programming environment. Frequency-time information for the start and end of individual phrases was marked manually and stored in a workstation for analysis. The middle phrases, after the first but before the last, were treated as elements of a single group.

For spectral analysis, the frequencies of the start and end of the first, middle, and last phrases were extracted for twitter calls at specific time points in the post-procedural period. The power spectra of native and altered twitter vocalizations were estimated using multitaper spectral estimation methods, assuming a time-bandwidth factor of 5 (Thomson, 1982). For temporal analysis, the interphrase (start to start) interval for the middle phrase group, the number of phrases, and the total call duration were extracted similarly.

Vocal reception

The frequency response area to simple tone bursts provides a basic description of spectral and temporal receptive field properties. A more complete receptive field description is possible by analyzing response profiles to complex vocalization and parametric FM stimuli. For each multiunit cluster, spike trains for specific stimulus conditions are collected from pseudorandomly interleaved trials to construct peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) of spike counts grouped in 2 ms time bins. Response profiles of multiunit clusters and population PSTH to native and altered vocalizations and parametric FM sweeps are analyzed for peak and mean firing rates, peak response latency, and half-width time interval. Responses to successive phrases of vocalized FM sweeps that constitute the twitter call and to each synthetic FM sweep rate and are evaluated separately and averaged.

For statistical analyses, the Welch modified two-sample t test for response profiles to tone bursts and two-way unbalanced ANOVAs for vocalizations and parametric FM sweeps with call type/FM sweep rate and experimental group as factors were used to evaluate for main effects and post hoc comparisons.

Responses to pure tones. For each penetration site, responses to the matrix of frequency-intensity combinations determined the frequency response area (Schreiner and Mendelson, 1990; Sutter and Schreiner, 1991, 1995), including the excitatory tuning curve. Typically, a brief phasic discharge was recorded 8-30 ms after tone burst onset for a range of frequencies within the boundary of the excitatory tuning curve. CF is the frequency of the tone that evokes a response at minimum threshold (hereafter, simply “threshold”). The maximum spike rate is the maximum rate at CF along the intensity axis. The threshold is the SPL of the quietest tone burst that evokes a response above the spontaneous activity. The latency is a measure of the asymptotic minimum of first spike time arrivals across the full range of stimulus levels at CF. At progressively higher intensities, the timing for first spike arrival reaches or approaches a minimum plateau (Heil, 1997; Heil and Irvine, 1997; Mendelson et al., 1997). The bandwidth of the excitatory receptive field is calculated from measurements of the upper and lower frequencies bounded by the tuning curve at 10 dB above threshold. Q10 is calculated by dividing CF by the linear bandwidth at 10 dB above threshold.

Responses to native and altered vocalizations. For individual multiunit analysis, the peak and mean firing rates and peak latency are computed for responses to phrases of the vocalization stimulus from the PSTH. The first phrase is excluded from analysis because it is rather variable across vocalizations. The peak firing rate is the maximum in the PSTH within a 140 ms time window after phrase onset. The mean firing rate is the average spike count over that time window. The peak latency for a phrase is the interval from the onset of the phrase to the peak firing rate. For population analysis, the population PSTH to a particular vocalization is computed by averaging individual multiunit PSTHs. The peak and mean firing rates and peak latencies are computed from population PSTHs for each phrase of a particular vocalization. From the population PSTHs, response half-widths to each phrase are calculated. The half-width is the duration of the interval at which the firing rate exceeds half of its maximum value. Because the responses to each subsequent phrase of a call are not different from each other, the average response amplitude and duration to a vocalization is computed by averaging the peak response to each phrase and the half-width to each phrase.

Responses to parametric FM sweeps. For individual multiunit analysis, the peak and mean firing rates and peak latency are computed for each stimulus condition from the PSTH. The mean firing rate is the average firing rate within a 160 ms window after FM response onset; the peak firing rate is the maximum in the PSTH. The peak latency is the time interval from the onset of the stimulus to the peak firing rate. For population analysis, the population PSTH is computed by averaging individual multiunit PSTHs. The firing rates and latencies are also computed from population PSTHs. From population PSTHs, response half-widths are determined. The response half-widths for parametric FM stimuli are defined in the same manner as that for vocalization phrases.

Tonotopic maps and cumulative area-frequency plots. Frequency spatial maps are reconstructed by using Voronoi-Dirichlet tessellation (Cheung et al., 2001). The cortical surface is divided into polygons, one for each recording site. The shape and bounded area of each polygon is determined by applying an optimization algorithm that minimizes the cumulative perimeter of all polygons. Each polygon reflects, with its size, the cortical area of the recording site and, with its color, the CF value. Small polygons indicate areas of dense sampling; large polygons reflect areas of sparse sampling. This method for map reconstruction presents an undistorted representation of CF values distributed across anatomic cortical space. A cumulative area-frequency plot is constructed by computing a running sum of polygon areas for associated CFs that are sorted in an ascending manner. In a scenario in which there is cortical expansion or overrepresentation of a certain frequency band, the cumulative area-frequency plot will show an abrupt rise. Where there is cortical underrepresentation, such as in feline anterior auditory field, the cumulative area-frequency plot will show a shallow rise or plateau (Imaizumi et al., 2004).

Results

Vocal production

Monkeys with surgically modified vocal tracts produced altered twitters that differed from native twitters most prominently in the spectral and temporal domains. Table 3 displays data for spectral and temporal features of twitter calls restricted to the beginning (native) and ending (final altered) data collection times and provides results of statistical comparisons between the two states. Figures 2 and 3 show intervening vocal production data to furnish qualitative insight into the evolution of altered twitter features in the post-procedural period. A quantitative analysis in this regard is beyond the scope of this report.

Table 3.

Native and altered vocal production

|

|

m03 |

m04 |

m40 |

m08 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks after voice modification | 35 | 50 | 23 | 28 |

| Spectral | ||||

| First phrase (kHz) | ||||

| Native start | 8.642 (0.186) | 7.126 (0.186) | 8.298 (0.116) | 7.74 (0.242) |

| Altered start | 1.321 (0.126) | 4.958 (0.233) | 5.423 (0.140) | 4.363 (0.130) |

| p value | * | * | * | * |

| Native end | 14.512 (0.135) | 12.819 (0.209) | 12.549 (0.153) | 13.386 (0.321) |

| Altered end | 2.177 (0.135) | 9.172 (0.428) | 8.047 (0.093) | 7.563 (0.060) |

| p value | * | * | * | * |

| Middle phrase (kHz) | ||||

| Native start | 5.553 (0.130) | 4.735 (0.177) | 5.479 (0.060) | 4.298 (0.112) |

| Altered start | 1.07 (0.130) | 2.381 (0.116) | 3.842 (0.056) | 2.251 (0.070) |

| p value | * | * | * | * |

| Native end | 13.405 (0.163) | 12.353 (0.228) | 10.828 (0.051) | 12.884 (0.293) |

| Altered end | 1.777 (0.144) | 8.112 (0.391) | 7.219 (0.060) | 5.786 (0.042) |

| p value | * | * | * | * |

| Last phrase (kHz) | ||||

| Native start | 5.712 (0.121) | 4.735 (0.107) | 5.46 (0.070) | 5.191 (0.130) |

| Altered start | 0.967 (0.098) | 3.367 (0.223) | 4.009 (0.074) | 3.423 (0.112) |

| p value | * | * | * | * |

| Native end | 9.749 (0.200) | 8.614 (0.177) | 7.842 (0.065) | 9.07 (0.237) |

| Altered end | 1.609 (0.098) | 6.493 (0.321) | 6.047 (0.558) | 5.47 (0.074) |

| p value | * | * | * | * |

| Temporal | ||||

| Mid interphrase interval (s) | ||||

| Native end | 0.130 (0.020) | 0.129 (0.017) | 0.112 (0.031) | 0.130 (0.020) |

| Altered end | 0.119 (0.003) | 0.131 (0.032) | 0.122 (0.012) | 0.133 (0.003) |

| p value | * | 0.72 | 0.07 | 0.42 |

| Number of phrases (count) | ||||

| Native end | 8.404 (1.296) | 10.207 (1.362) | 8.066 (1.347) | 10.272 (1.953) |

| Altered end | 6.554 (1.559) | 13.371 (1.362) | 8.244 (1.080) | 12.000 (1.789) |

| p value | * | * | 0.44 | * |

| Total call duration (s) | ||||

| Native end | 1.030 (0.185) | 1.228 (0.192) | 0.879 (0.167) | 1.257 (0.257) |

| Altered end | 0.863 (0.248) | 1.729 (0.320) | 0.940 (0.152) | 1.484 (0.236) |

|

p value |

* |

* |

0.05 |

* |

Mean (SD) convention. *p <0.01; Welch modified two-sample t test.

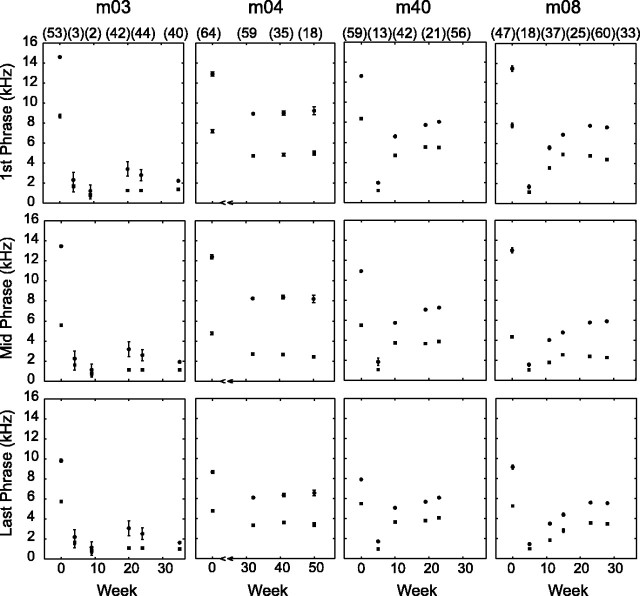

Figure 2.

Spectral features of altered vocalizations. The numbers in parentheses at the top of the boxes indicate sample size. Top and bottom symbols indicate the mean and SD of the start and end frequencies of phrases, respectively. Early in the post-procedural period, voiced FM sweeps were severely degraded. Over a 4-5 month period, increasingly stable spectrally restricted phrases were voiced. Beyond this, altered twitter calls contained minimum frequencies that were downward shifted by ∼1 octave.

Figure 3.

Temporal features of altered vocalizations. Interphrase intervals were unchanged. Early on, the number of phrases and total call duration fell below native values but stabilized after 4-5 months. m04 and m08 voiced more phrases and lengthier calls. In contrast, m03 voiced fewer phrases and briefer calls. For these monkeys, the difference in the number of phrases was between two and three. Motor output to guide twitter call production appeared to have been impacted by the peripheral voice tract modification procedure.

In the spectral domain, Figure 1 shows spectrograms of native and altered twitter calls for voice-modified experimental monkeys. These vocalizations were used as stimuli for electrophysiological mapping experiments (Table 1). The power spectra of native (Fig. 1, green) and altered (Fig. 1, blue) twitter calls are shown in the right column. In three of four cases, the spectral envelope is similar for both types of twitter calls within individual monkeys. In all monkeys, the altered calls are shifted to lower frequencies.

Figure 2 shows the start and end frequencies of the first, middle, and last phrase groups at specific times in the post-procedural period (sample size is in parentheses at the top of the first row of boxes). Early after voice modification, the monkeys produced highly abnormal twitter calls that were low-pitched glottal pulses with severely degraded FM structure (m03, m40, and m08; data not shown for m04). Over several months, the monkeys (except m03) gradually refined their twitter call production and generated increasingly stereotyped vocalizations. After 4-5 months, altered twitter calls stabilized. With the exception of m03, the monkeys successfully produced spectrally restricted upward rising FM sweeps that were qualitatively similar to native phrases. The altered twitter calls have spectral energy <3 kHz in three of four cases (Table 3). Collectively, twitter call minimum frequency [mean (SD)] was 4.90 (0.51) kHz for the native group and 2.46 (0.92) kHz for the altered group (p < 0.01). The vocal tract modification procedure permanently lowered the minimum frequency of the twitter call by ∼1 octave.

In the temporal domain, Figure 3 shows the middle phrase group interphrase interval, the number of phrases, and the total call duration at the same specific times in the post-procedural period as in Figure 2. Interphrase intervals were unchanged for all monkeys (Table 3), except m03, which had a minor but statistically significant 0.01 s difference. In the early post-procedural period, the phrase number and total call duration fell below native values. These temporal features stabilized after 4-5 months, mirroring spectral changes. The number of phrases was higher and the total call duration was longer for m04 and m08, suggesting a form of stuttering as a consequence of altered sensory feedback. Paradoxically, m03 voiced fewer phrases and briefer calls in its altered state. For the three cases with temporal feature changes, the difference in the number of phrases was between two and three. In view of the extension and reduction of twitter call durations without change in interphrase intervals, it appears that the peripheral voice tract alteration procedure affects central motor stations that guide twitter call production.

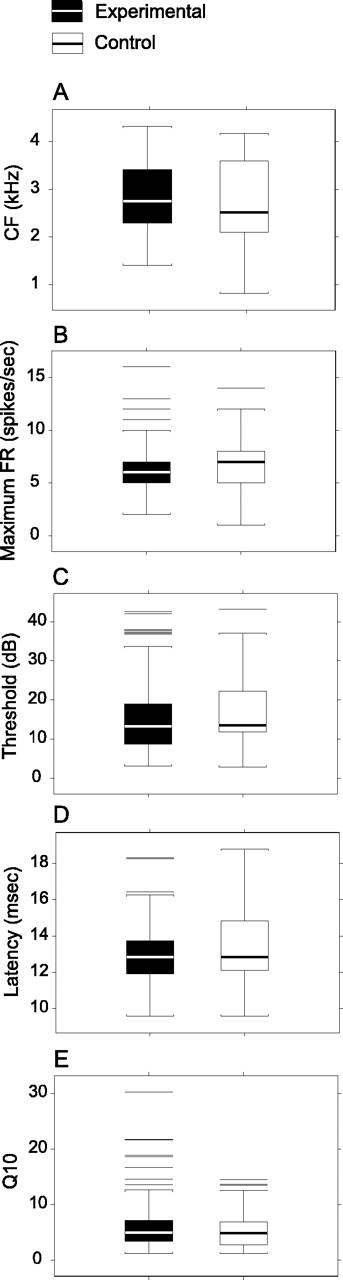

Responses to pure tones

Pure tone response profiles for the experimental and control groups are nearly indistinguishable. Figure 4 shows results of response parameters CF, maximum firing rate, threshold, minimum latency, and Q10 to pure tone stimulation in Tukey box plots, in which the bottom and top ends of the box are the limits of the lower and upper quartiles and the line inside the box is the median. The connected lines beyond the box are the largest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range, and lines beyond these boundaries are outside values at the extreme tails of the distribution (Cleveland, 1994). Table 4 details descriptive statistics for the five parameters. Figure 4A and the first column of Table 4 show the CF distributions and means of experimental and control monkeys to be similar, so comparisons between the two groups are valid. Statistically, the maximum firing rate and latency are different (p < 0.05; Welch modified t test). In the experimental group, the average maximum firing rate and latency are decreased by 10.7 and 3.7%, respectively, compared with the control group. Physiologically, these differences are quite small, and, consequently, cortical neurons of voice-modified monkeys can-not be easily distinguished from normal monkeys when receptive field properties are probed by pure tone stimuli. Q10 is indistinguishable between the two groups.

Figure 4.

Response parameters to tone bursts are nearly indistinguishable. A, CF or tone frequency that evokes a response at minimum threshold. B, Maximum FR at CF along the stimulus intensity axis. C, Threshold is the lowest sound pressure that evokes a response above spontaneous activity. D, Latency is asymptotic first spike arrival time with increasing stimulus intensity. E, Q10 is bandwidth of the excitatory receptive field that is computed by taking the linear bandwidth at 10 dB above minimum threshold and dividing by CF. The average maximum firing rate is decreased by 10.7%, and latency is decreased by 3.7% (p < 0.05) compared with controls. Physiologically, these differences are small.

Table 4.

Pure tone response summary statistics and comparisons

|

|

CF (kHz) |

Maximum rate (spikes/s) |

Threshold (dB) |

Latency (ms) |

Q10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | 2.85 (0.71) | 6.2 (2.1) | 15.8 (8.1) | 12.9 (1.4) | 5.7 (3.4) |

| Control | 2.77 (0.87) | 6.9 (2.4) | 16.1 (7.9) | 13.4 (1.9) | 5.2 (3.1) |

|

p value |

0.464 |

0.038 |

0.732 |

0.046 |

0.236 |

Mean (SD) convention. p values were derived from the Welch modified two-sample t test.

For threshold, Figure 4 shows the experimental group to have a slightly lower quartile value. However, the overall threshold distributions for both groups are substantively similar (mean, ∼16 dB; p = 0.732; upper quartile, ∼20 dB) (Table 4, Fig. 4). The neuronal thresholds for CF <4.3 kHz are in close agreement with audiogram values for the 2-5 kHz frequency band (Seiden, 1957). Given that vocalization and synthetic FM sweep stimuli (∼52 dBA SPL) were delivered generally at least 15 dB above threshold to all study monkeys, any differences in response strength or temporal precision between the two groups cannot be accounted for by minor and statistically insignificant differences in neuronal thresholds.

Monkey m76

Data from m76 are shown separately because, unlike experiments in study monkeys, the sampling range covers the full extent of AI (CF: 0.8-4.3 kHz, 28 units; 4.3-18 kHz, 126 units). The data set is partitioned at a CF of 4.3 kHz, because native twitter calls have little energy below this frequency. This monkey provides an opportunity to assess for tonotopic map distortion (see Fig. 10) and to evaluate how plastic changes might impact AI (Fig. 5) within a specific sector (CF <4.3 kHz) and as a whole. For pure tone stimuli, the threshold (SD) for CF <4.3 kHz is 32.8 (12.9) dB SPL and for CF >4.3 kHz is 23.1 (9.5) dB SPL (p < 0.01). The significant difference in threshold between the two CF ranges is expected because relative inefficiencies in middle ear transfer functions at the lower frequencies are reflected in both marmoset audiogram thresholds and neuronal activation levels (Seiden, 1957; Wang et al., 1995). Overall, the neuronal thresholds for m76 are higher than expected when compared with experimental monkeys (Fig. 4) and may reflect an idiosyncratic variation. Q10 (SD) for CF <4.3 kHz is 3.1 (1.5) and for CF >4.3 kHz is 7.4 (5.2) (p < 0.01), which is also expected because lower-frequency neurons tend to be more broadly tuned compared with higher-frequency neurons (Schreiner, 1998; Recanzone et al., 1999; Cheung et al., 2001). The maximum firing rate (SD) for CF <4.3 kHz is 6.6 (2.8) spikes/s and for CF >4.3 kHz is 7.6 (3.3) spikes/s (p = 0.10), and the latency (SD) for CF <4.3 kHz is 12.9 (1.4) msec and for CF >4.3 kHz is 12.4 (1.2) msec (p = 0.07), which are indistinguishable for the two CF ranges.

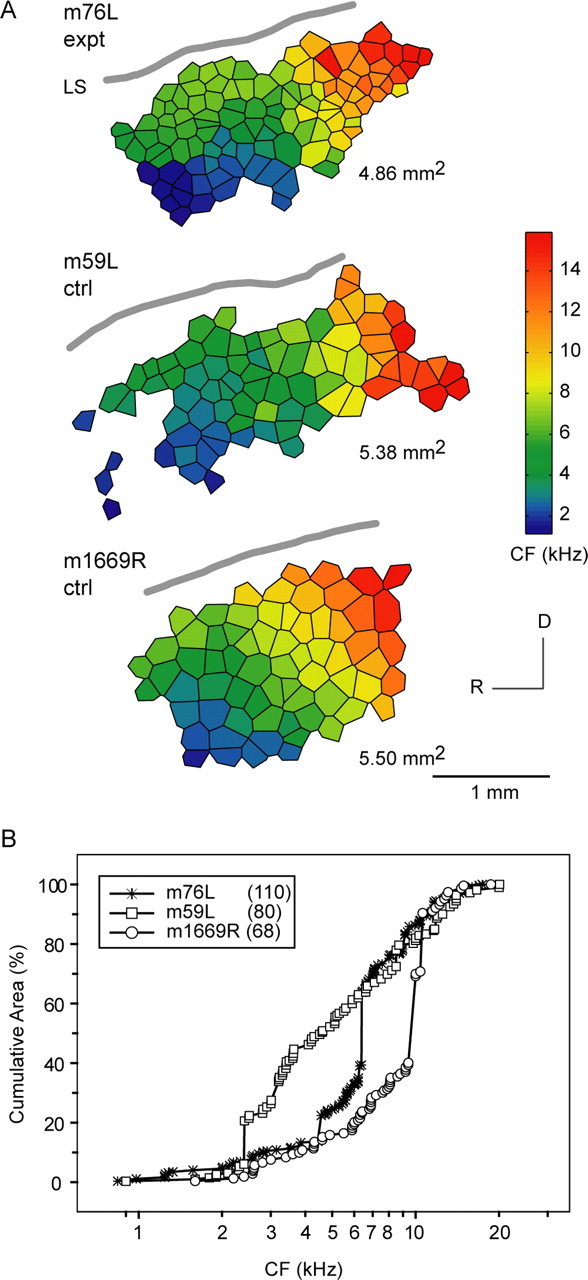

Figure 10.

Tonotopic map for m76 is not distorted. A, Full AI tonotopic maps from one voiced-modified monkey (m76L) and two normal monkeys. There is smooth isofrequency contour progression across the cortical surface in all three monkeys. AI areal extent is slightly larger in control monkeys compared with m76L. B, Normalized cumulative area-frequency plots show underrepresentation (plateau) of CF <2 kHz in all three monkeys. The cumulative area-frequency plot for m76L resides within the two plots for normal monkeys, so tonotopic map distortion for this voiced-altered monkey is unlikely. AI areal measure is expressed in square millimeters. R, Rostral; D, dorsal; LS, lateral sulcus; expt, experimental; ctrl, control. The number in parentheses indicates the number of neuronal units.

Figure 5A displays spectrograms of m76 native and altered twitter calls. The spectral envelopes (data not shown) for the calls are similar, with the altered call shifted to lower frequencies. This finding is consistent with results in the experimental group (Fig. 1, right column). Figure 5, B and C, shows PSTHs of responses to the vocalizations. For the altered call stimulus condition, the peak firing rate [mean (SEM) in spikes/unit/second] is 23.6 (4.7) for CF <4.3 kHz and 32.0 (3.7) for CF >4.3 kHz. The difference, although modest, is significant (p < 0.01) and suggests differential activation profiles for neurons above and below a CF of 4.3 kHz. In contrast, for the native call stimulus condition, the peak firing rate is 8.5 (0.7) for CF <4.3 kHz and 51.0 (11.2) for CF >4.3 kHz. The difference is statistically significant (p < 0.01). Figure 5C shows that neurons with CF <4.3 kHz (left) are only weakly driven by the native twitter call, whereas the altered call, which has a spectral energy <5 kHz, evokes (right) discernible spike activity in them. Therefore, the altered twitter call activates unambiguous responses from cortical neurons that normally are only weakly activated by native twitter calls. Although data from m76 also indicate reorganization of neurons with CF >4.3 kHz, no firm conclusion can be drawn from this single case, and additional studies are necessary to rule out any idiosyncratic effects in this monkey. Subsequent mapping procedures in study monkeys target neurons with CF <4.3 kHz, because they are exposed to new, self-generated, complex communication sound stimuli and may be engaged in auditory learning of altered twitters.

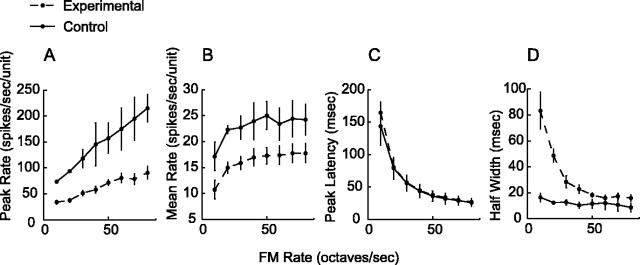

Responses to vocalizations

Neurons with CF <4.3 kHz are poorly activated by native twitter calls. An analysis of the four experimental and two control monkeys with recordings directed at neurons with CF <4.3 kHz appears below.

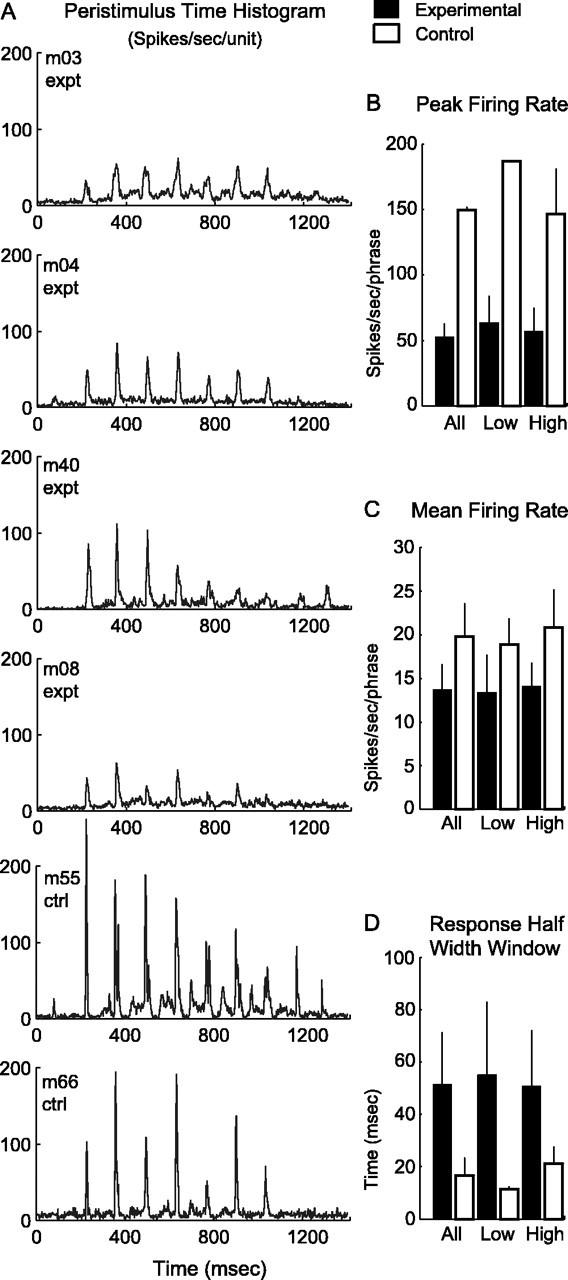

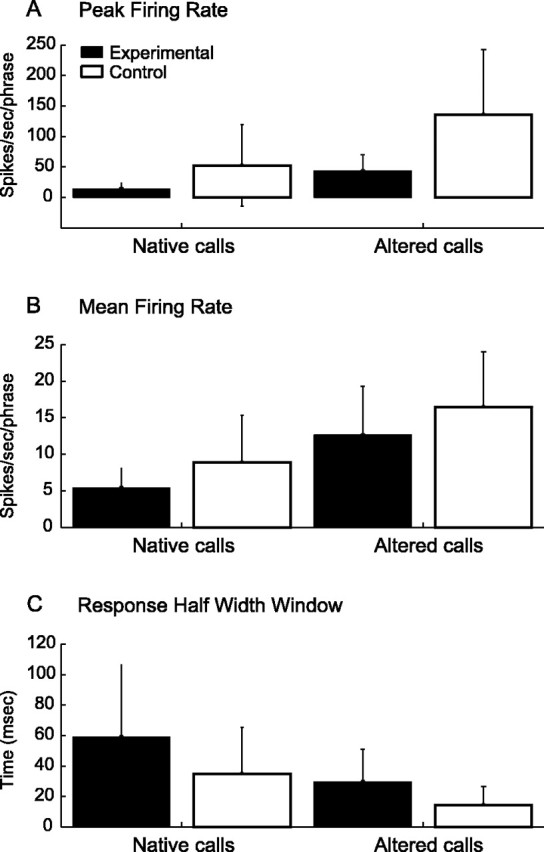

The response profiles of experimental and control monkeys stimulated with an altered twitter call differ. Experimental monkeys have reduced peak and mean firing rates and wider half-width response windows. Figure 6A shows PSTHs of responses to the m08 altered twitter call. All voice-modified experimental monkeys show reduced spike rate activity to m08 altered call stimulation (Fig. 6B,C). The peak and mean firing rates per phrase are significantly higher for the control group (all neurons, CF <4.3 kHz). The possibility of a biased subpopulation effect is evaluated by assigning neurons to low CF (<2.5 kHz) and high CF (2.5-4.3 kHz) categories, respectively. No subpopulation effect is evident, and experimental monkeys have lower peak and mean firing rates in all data categories (all p < 0.01). Furthermore, the experimental group has a wider response half-width window (Fig. 6D) compared with the normal group, and again there is no subpopulation bias (all p < 0.01). Reduction in the peak and mean firing rates and broadening of the half-width response window are observed for voice-modified monkeys collectively. Figure 7A-C shows the peak and mean firing rates and half-width windows, respectively, for responses to all native and altered twitter call stimuli. The results corroborate findings for the example case in Figure 6. Voice-modified monkeys stimulated with altered calls have a 21% decrease in mean spike rate, 68% reduction in peak firing rate, and a 107% increase in half-width response window duration (p < 0.01 for all comparisons). The decrement in the peak firing rate represents the combined effects of reduction and dispersion of spike activity after response interval widening. Qualitatively similar results are observed for evoked neuronal activity to native call stimuli. Overall, these results indicate that evoked response depression and temporal precision degradation are changes in cortical neuron receptive field properties of voice-modified monkeys when probed by both native and altered twitter calls.

Figure 6.

Response profiles of voice-modified and normal monkeys to the m08 altered twitter call stimulus. A, Population PSTHs for four experimental and two control monkeys. Note the reduction in spike rate and temporal precision for the experimental group. B-D, Data are evaluated for possible subpopulation bias by separating neurons into low CF (<2.5 kHz) and high CF (2.5-4.3 kHz) categories. B, Peak firing rate is consistently lower for the experimental group. C, Mean firing rate results corroborate well with the findings in B. D, Response half-width window is wider for experimental monkeys across CF subpopulation categories. There is no subpopulation bias in all comparisons (all p < 0.01). expt, Experimental; ctrl, control. Error bars indicate SD.

Figure 7.

Peak and mean firing rates and response half-width window to all native and altered twitter call stimuli for experimental and control groups. Refer to Figure 1 and Table 1 for the entire stimulus set. A, Peak firing rate is lower for experimental monkeys to both native and altered call stimuli (native and altered call comparisons by monkey group; p < 0.01). B, Mean firing rate is also lower in experimental monkeys to the two vocalization stimuli (native call comparison by monkey group, p < 0.01; altered call comparison by monkey group, p < 0.05). C, Response half-width window is wider for the experimental group for both types of stimuli (native and altered call comparisons by monkey group; p < 0.01). Error bars indicate SD.

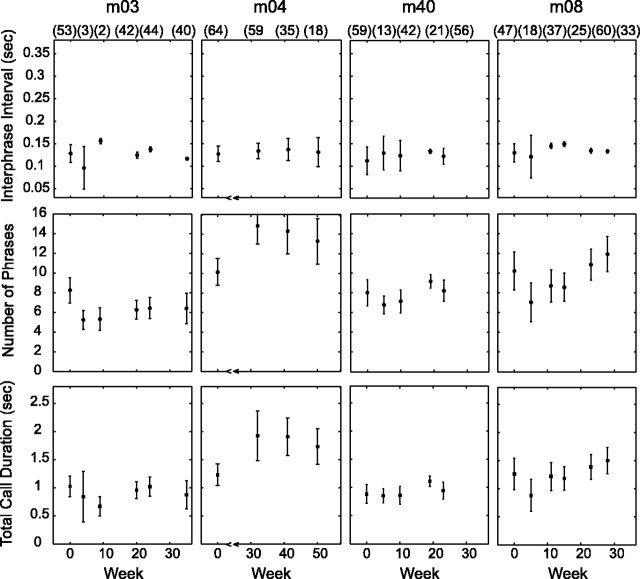

Responses to parametric FM sweeps

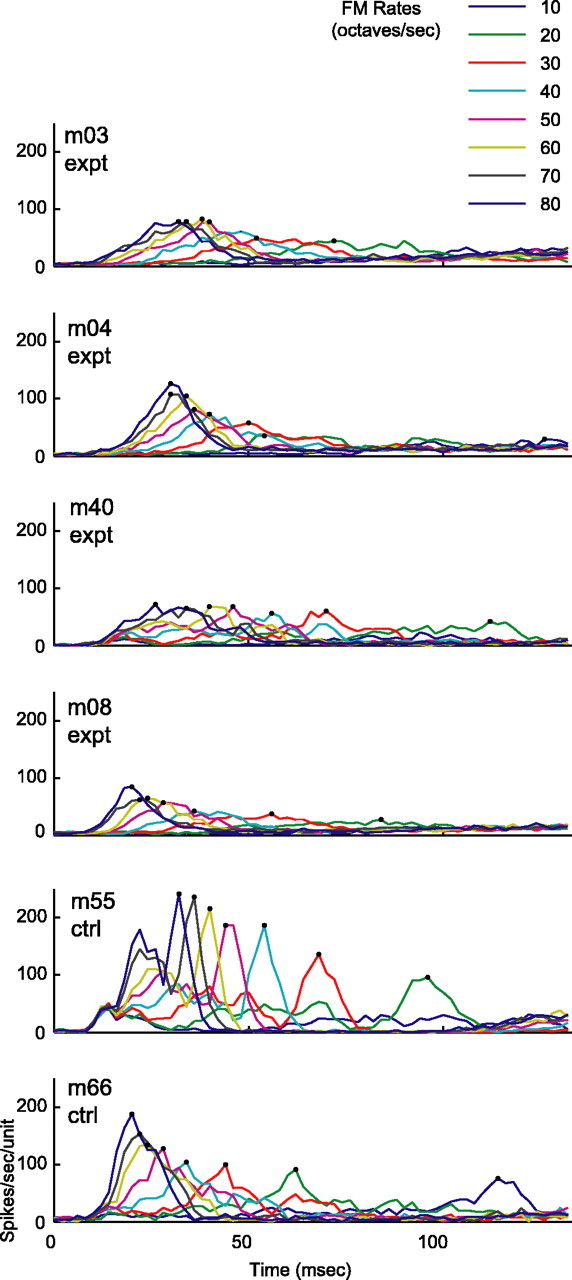

Twitter calls are composed of a series of FM sweeps (Fig. 1). Are cortical response alterations specific to vocalizations or are they generalized to isolated, synthetic FM sweeps? Figure 8 shows PSTH response profiles to parametric FM stimuli that range from 10 to 80 octaves/s in 10 octaves/s step increments for all monkeys. A different color is assigned for each parametric FM sweep rate. The dots mark the timing to peak responses for specific FM rates. Globally, experimental monkeys have reduced spike rates and wider response windows at the lower parametric FM rates. Figure 9A-D quantifies responses to parametric FM sweeps. Figure 9, A and B, shows voice-modified monkeys have lower peak and mean spike rates compared with control monkeys for all FM rates (all p < 0.001). Figure 9C shows the peak latencies of the experimental and control groups to be well matched for all FM rates. Figure 9D illustrates that the half-width response windows are wider for FM rates 10-40 octaves/s for voice-modified monkeys (p < 0.05 for 10 octaves/s; p < 0.01 for 20-40 octaves/s; p > 0.10 for 50-80 octaves/s).

Figure 8.

Population PSTH to parametric FM rates that range from 10 to 80 octaves/s. Individual FM rates are assigned specific colors. Time-to-peak responses are marked with dots. Overall, the spike rates for the experimental group are globally reduced for all FM rates, and the response window appears to be wider for the slower FM sweeps.

Figure 9.

Response profiles to parametric FM rates. A, Peak spike rates are reduced in the experimental group for all FM rates (all p < 0.001). B, Mean firing rates are also reduced for the experimental group. The results are similar to A (all p < 0.001). C, Peak latencies of the experimental and control groups are well matched for all FM rates. D, Half-width response windows are wider for FM rates 10-40 octaves/s for voice-modified monkeys (p < 0.05 for 10 octaves/s and p < 0.01 for 20-40 octaves/s). Dashed line, Experimental; Solid line, control.

In summary, cortical neurons in voice-modified monkeys are virtually indistinct from control monkeys when receptive field properties are determined by using simple tone burst stimuli. Differences become evident when more complex and ethologically relevant stimuli, such as complex communication calls and FM sweeps, are used to probe response properties. Here, cortical neurons in the experimental group have reduced firing rates and extended temporal response windows to native and altered twitter calls and FM sweeps.

Tonotopic maps

Tonotopic map distortion in AI is not evident in voiced-modified monkeys. Figure 10A shows full AI tonotopic maps from one voice-modified monkey (m76L: 0.8 < CF < 18 kHz, 110 units) and two normal monkeys (m59L: 0.9 < CF < 20 kHz, 80 units; m1669R: 1.6 < CF < 19 kHz, 68 units). In m76, the RH data set is incomplete, so only the LH AI frequency map is reconstructed and analyzed. The maps are oriented with the observer facing the LH. All maps exhibit a smooth, fan-shaped progression of isofrequency contours from low to high along a rostroventral to dorsocaudal trajectory. AI areal extent for m76L (∼4.9 mm2) is slightly smaller than for control monkeys (∼5.4 mm2). A normalized cumulative area-frequency plot (percentage of total area) is shown in Figure 10B to assess for underrepresentation and overrepresentation of certain frequency bands. There is note-worthy underrepresentation (plateau) of CF <2 kHz in all three monkeys. The cumulative area-frequency plot for m76L resides within the two plots for normal monkeys. There is no unambiguous evidence for tonotopic map distortion in m76L, a voiced-modified monkey.

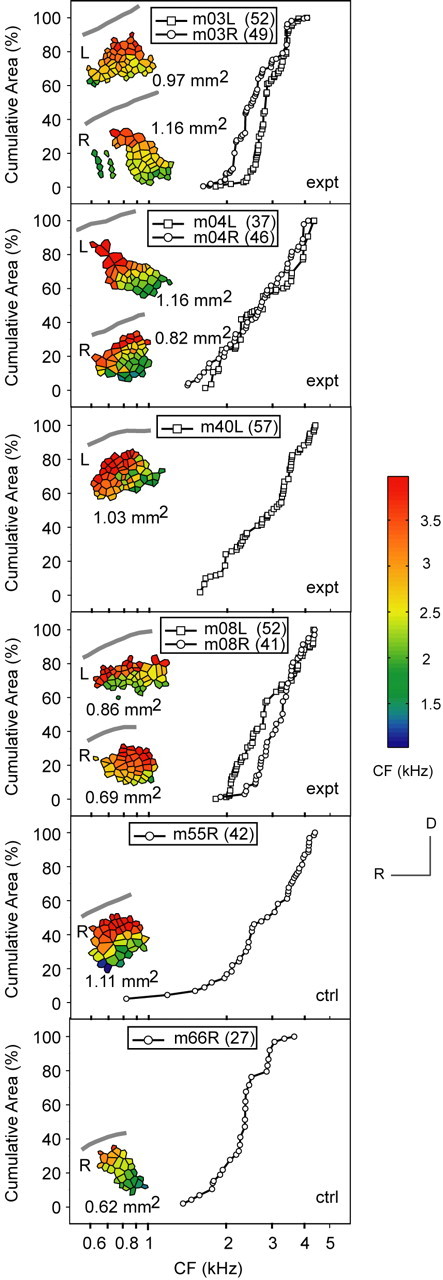

Figure 11 shows partial maps with CF <4.3 kHz for experimental and control monkeys to evaluate for tonotopic map change within this sector. The RH has been reoriented to facilitate direct comparison with the LH. The CF ranges mostly from 1.4 to 4.3 kHz, and AI areal extent ranges from 0.62 to 1.16 mm2 for maps in both groups. The number of neuronal units for each map is displayed in an inset box (Fig. 11). Control monkeys m55R and m66R exhibit a shallow cumulative area rise for CF <2 kHz, which is consistent with results shown in Figure 10B and confirms underrepresentation of these neurons in AI. There is a linear rise of cumulative cortical area for CF from 2 to 4 kHz in experimental and control monkeys, without a plateau or rapid upward deflection in any case. In monkeys with bihemispheric data, left and right cumulative-frequency area plots are qualitatively similar. In experimental animals, there is no underrepresentation or overrepresentation of a subpopulation of neurons for CF <4.3 kHz.

Figure 11.

Tonotopic maps in experimental animals are not distorted. Tessellated frequency maps for CF < 4.3 kHz with AI areal measurements in square millimeters are presented as insets in cumulative area-frequency subplots. The lateral sulcus is marked with a gray curve. Control monkeys m55R and m66R confirm underrepresentation of CF <2 kHz (shallow rise). A linear rise in the cumulative cortical area for CF from 2 to 4 kHz is observed for both experimental and control monkeys. There is no plateau or rapid upward deflection in any case to indicate a subpopulation contraction or expansion. In monkeys with bihemispheric data, left and right cumulative area-frequency plots are qualitatively similar. L, Left; R, right; expt, experimental; ctrl, control. The number in parentheses indicates the number of neuronal units.

In summary, complete and partial AI tonotopic maps for control and voice-modified monkeys show smooth progression of CF isofrequency contours and no evidence for map distortion. A detailed examination of tonotopic maps for CF <4.3 kHz in both groups does not indicate a subpopulation expansion or contraction in experimental monkeys. Taken as a whole, voice-modified monkeys have tonotopic maps that are indistinguishable from normal variants.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that highly vocal New World monkeys with surgically modified voice production apparati produce spectrally altered calls and exhibit profound sensory cortical representation changes that are specific to higher-order processes involved in discrimination of more complex sounds. The experimental group shows (1) reduction of response strength to complex sounds, encompassing native and altered twitter calls, and synthetic FM sweeps that mimic the phrase component of twitters; (2) reduction in temporal precision of neuronal responses to these complex sounds; (3) nearly normal response profiles to pure tones; and (4) undistorted tonotopic map organization.

Response magnitude and temporal dispersion

Response magnitude and temporal dispersion to native and altered vocalizations and parametric FM sweep stimuli are the two principal measurements. The mean firing rate is derived over a period corresponding to the fastest phrase repetition rate of native or altered vocalizations (∼12 Hz) and averaged over all phrases per vocalization, except for the first. The initial phrase spectral content and its associated interphrase interval deviate from the more stable set of middle phrases (Fig. 1) and are excluded from the final analysis. However, the inclusion of the first phrase and interval does not change the results qualitatively. The peak firing rate is featured as a response measure because it captures very clearly the phasic nature of evoked activity to call phrases and FM sweeps. Yet, the peak firing rate may be influenced by the observed widening of the half-width response window or increased temporal dispersion. Clarification of this confound is addressed by using the mean firing rate measure, which uses an estimation window that is longer than the half-width response window. The results show that the mean firing rate is also decreased for experimental monkeys. Thus, response peak magnitude is decreased and temporal dispersion is increased in the experimental group.

The reduction in response temporal precision in experimental monkeys cannot be attributed to changes in temporal structure of the stimuli (interphrase intervals unchanged) (Table 3), reduction of overall stimulus energy (delivered at 52 ± 2 dBA for vocalizations and FM sweeps), or temporal precision degradation as a result of peripheral hearing loss. Vocal tract modification does not impart peripheral hearing loss. In fact, cortical neuron response threshold and latency distributions for pure tone stimuli are essentially the same for the experimental and control groups. Therefore, the reduction in temporal precision to complex sounds in experimental monkeys is likely a central auditory phenomenon.

The reduction in firing rates to vocalization stimuli in experimental monkeys must be interpreted in the context of acoustic structure changes in altered twitter calls that may account for response profile differences. The two principal issues are (1) energy spectra relationship for native and altered calls and (2) alteration in the balance of excitation provided by the lowest formant and inhibitory action provided by the higher formants. Power spectrum plots for native and altered calls are shown in the third column of Figure 1. The spectral content or spectral envelope for both types of calls is similar in individual monkeys. The main difference is a shift of the altered calls to lower frequencies. This may result in an altered balance of excitatory and inhibitory forces in the frequency area differentially occupied by altered calls. However, instantaneous changes in the balance of excitation and inhibition attributable to differences in spectral energy distribution cannot account for the observed response changes. All experimental monkeys have reduced response strength and broader half-width response windows to both altered and native twitter calls. Conversely, control monkeys respond just as strongly and precisely to altered and native calls (Fig. 6). This suggests a global alteration in representation of broadband sounds that are little affected by details of broad spectral envelopes. In general, the mechanisms underlying the observed response changes have to be sensitive to some aspects of the stimulus spectrum, because narrowband stimuli are virtually not affected. This suggests that higher-order receptive field properties particularly pertinent for the processing of complex sound attributes can be changed independently from other more general properties of sound processing that are captured by pure tone stimulus probes.

The success of altered twitter calls produced by experimental monkeys to inspire social contact and acceptance by other monkeys may be modest. Altered twitter calls may be viewed by conspecific monkeys as frankly aversive and lead to social isolation. Under this circumstance, voice-modified monkeys are motivated to increase voicing rehearsal frequency and refine their altered twitter call sound structure and repertoire to improve social acceptance. The consequence of affiliative communication isolation on highly vocal New World monkeys is undoubtedly negative and impacts on modulation of sensory cortical plasticity mechanisms, such as via activation of the amygdala and the nucleus basalis. Drawing from sensory learning studies (Buonomano and Merzenich, 1998; Kilgard and Merzenich, 1998b; Kilgard et al., 2001), the predicted outcomes for cortical responses to highly repetitive and behaviorally relevant stimuli in the experimental group are as follows: (1) increase in response strength to altered twitters; and (2) decrease in response strength to normal twitters. This was not observed, which indicates the involvement of other or altered plasticity mechanisms beyond the common activity-dependent sensory learning model.

Motor and sensorimotor learning

Use-dependent modification of motor cortex functional topography is a potential consequence of laryngeal modification. A variety of experimental manipulations, including peripheral or central injury, electrical stimulation, pharmacological intervention, and behavioral experience have been shown to alter motor maps (Nudo, 1997; Schieber and Deuel, 1997; Friel and Nudo, 1998). Repetitive motor activity alone does not appear to produce functional reorganization of motor maps (Plautz et al., 2000). In this study, incremental changes in the sound structure of altered twitter calls over months suggest compensatory skill acquisition, or motor learning, in an effort to reconstitute more normal calls.

Studies in songbirds and humans have demonstrated that learning and maintenance of vocal behavior are critically dependent on auditory feedback (Konishi, 1965; Marler and Sherman, 1983; Houde and Jordan, 1998; Brainard and Doupe, 2000a,b). Deafness in children, during and after speech acquisition, results in deterioration of speech production (Waldstein, 1990; Cowie and Douglas-Cowie, 1992). Although deafened adults continue to produce intelligible speech, certain aspects of their speech begin to degrade soon after deafness (Cowie and Douglas-Cowie, 1992; Matthies et al., 1996; Lane et al., 1997). By the same token, temporal perturbations in the range of 100-150 ms in auditory feedback elicit compensatory pitch adjustments (Elman, 1981; Burnett et al., 1998; Jones and Munhall, 2000, 2003). Spectral shifts in auditory feedback will cause the speaker to modify the frequency content of his produced speech toward the altered input (Gracco, 1994). Alterations in perceived formants induce compensatory changes in vowel production (Houde, 1997; Houde and Jordan, 1997, 1998, 2002). Similarly, deafness in birds during song learning interferes strongly with the production of a viable and stable song (Nordeen and Nordeen, 1992; Brainard and Doupe, 2000a,b; Lombardino and Nottebohm, 2000). These behavioral studies indicate that auditory feedback is integral to speech/vocal production and is directly involved in the dynamic control of some aspects of voicing.

The ability to correct vocalization errors through evaluation of vocalized auditory signals has been demonstrated in songbirds (Konishi, 1965; Nordeen and Nordeen, 1992; Leonardo and Konishi, 1999). Mismatch of actual vocalization with an internal model has been hypothesized to create an error signal that is used to alter the motor program that aims to reduce and eventually eliminate such a mismatch (Brainard and Doupe, 2000a).

In the current study on marmoset monkeys, the most salient mismatch between feedback and target twitter calls is in the spectral domain; the minimum frequency content of altered calls is permanently lowered and cannot be compensated for by central motor reorganization. It is plausible that error signals arising from mismatches are proportional to the observed changes in AI in the form of response reduction and temporal imprecision to vocalization and FM stimuli.

In monkeys, activity in AI is found to be inhibited by either electrically evoked or spontaneous vocalizations (Müller-Preuss and Ploog, 1981; Ploog, 1981; Jürgens and Lu, 1993; Jürgens, 1998, 2000, 2002; Eliades and Wang, 2003). Individual cortical neurons exhibit a variety of modulations during vocalizations ranging from suppression to excitation (Eliades and Wang, 2003). Cortical response alterations observed in our experimental monkeys may be a direct and long-term consequence of the suppression of responses that occurs during vocalization. In effect, monkeys could be considered “trapped” in a perpetual voicing mental rehearsal state where the target communication sound cannot be reached. Two possible mechanisms have been proposed for response suppression in AI during vocalization. One possibility is that activity in the auditory system is generally suppressed during vocalization. Alternatively, response reduction during vocal production results from a comparison between actual and predicted auditory feedback (i.e., an auditory version of Held's “reafference hypothesis”) (Hein and Held, 1963). Motor system activity during vocalization may generate an internal representation of the expected auditory feedback, and a match between expected and actual feedback may release suppressed cortical responses.

Another explanation of the observed cortical plasticity may relate to general aspects of stimulus conditioning and associative learning. Some forms of cortical reorganization may be interpreted as behaviorally contingent neural enhancement and suppression processes that are modulated by the probability that a particular signal predicts a reward (Blake et al., 2002; Beitel et al., 2003). The substrate for enhancement and suppression could be in excitatory and inhibitory effects of existing networks or from newly formed, learning-induced connectivities (Trachtenberg et al., 2002). Enhancement is often expressed by increased firing rate and temporal precision, especially noticeable at response onset (Recanzone et al., 1992; Beitel et al., 2003). Suppression is manifested by decreased spike activity and temporal imprecision in discharge synchrony. In normal monkeys, cortical representations of species-specific vocalizations are expressed by robust responses with high temporal precision. The reward for successful communicative interchange reinforces vigorous and temporally sharp cortical representations. In voice-modified monkeys, lack of reward for voicing well rehearsed and heard twitters over several months that are, nevertheless, communicatively ineffective weakens representations and degrades their temporal precision. The suppressive effect appears to generalize to normal twitter calls and synthetic FM sweeps but not to pure tones. In this context, suppressive changes observed in cortical responses of voice-modified monkeys may be interpreted in pavlovian terms of reward-dependent plasticity (Rescorla and Solomon, 1967; Pearce and Hall, 1980; Blake et al., 2002; Beitel et al., 2003).

Conclusion and perspectives

Vocal learning is a fundamental property of human communication. There are strong similarities in basic principles of learning between human speech and animal vocalization, in particular the songbird system (Doupe and Kuhl, 1999). This is especially true at the level of experience-dependent encoding of sensory inputs and formation of vocal outputs. This study provides evidence for an intimate dependence of primary sensory representation on primate vocal production. At this stage, the development of specific hypotheses involving associative learning, mismatch between motor and/or sensory templates, and feedback impact on AI representations requires more information from behavioral and physiological approaches. The observation of a link between motor output and sensory encoding of complex vocalizations in combination with the rich set of experimental approaches offered in the songbird system provides an opportunity to establish a primate model of sensorimotor learning that complements human speech and avian vocal learning studies.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Deafness Research Foundation, American Hearing Research Foundation, University of California San Francisco Academic Senate, Coleman Fund, Hearing Research Incorporated, Montgomery Street Foundation, Veterans Affairs Medical Research (S.W.C.), and National Institutes of Health Grant NS 34835 (C.E.S.). We thank Michael S. Brainard and Jeffery A. Winer for comments on this manuscript, Ralph E. Beitel for help with experiments, Xiaoqin Wang for discussions, and David A. Copenhaver and David T. Blake for assistance with data analysis.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Steven W. Cheung, Division of Otology, Neurotology, and Skull Base Surgery, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, Box 0342, A730, 400 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94143-0342. E-mail: scheung@ohns.ucsf.edu.

Copyright © 2005 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/05/252490-14$15.00/0

References

- Bao S, Chan VT, Merzenich MM (2001) Cortical remodelling induced by activity of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons. Nature 412: 79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitel RE, Schreiner CE, Cheung SW, Wang X, Merzenich MM (2003) Reward-dependent plasticity in the primary auditory cortex of adult monkeys trained to discriminate temporally modulated signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 11070-11075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DT, Strata F, Churchland AK, Merzenich MM (2002) Neural correlates of instrumental learning in primary auditory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 10114-10119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard MS, Doupe AJ (2000a) Auditory feedback in learning and maintenance of vocal behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 1: 31-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard MS, Doupe AJ (2000b) Interruption of a basal ganglia-forebrain circuit prevents plasticity of learned vocalizations. Nature 404: 762-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonomano DV, Merzenich MM (1998) Cortical plasticity: from synapses to maps. Annu Rev Neurosci 21: 149-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett TA, Freedland MB, Larson CR, Hain TC (1998) Voice F0 responses to manipulations in pitch feedback. J Acoust Soc Am 103: 3153-3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung SW, Bedenbaugh PH, Nagarajan SS, Schreiner CE (2001) Functional organization of squirrel monkey primary auditory cortex: responses to pure tones. J Neurophysiol 85: 1732-1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland WS (1994) The elements of graphing data. Summit, NJ: Hobart.

- Cowie R, Douglas-Cowie E (1992) Postlingually acquired deafness: speech deterioration and the wider consequences. In: Trends in linguistics: studies and monographs, No 62 (Winter W, ed), pp 75-85. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Crair MC, Gillespie DC, Stryker MP (1998) The role of visual experience in the development of columns in cat visual cortex. Science 279: 566-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimyan MA, Weinberger NM (1999) Basal forebrain stimulation induces discriminative receptive field plasticity in the auditory cortex. Behav Neurosci 113: 691-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupe AJ, Kuhl PK (1999) Birdsong and human speech: common themes and mechanisms. Annu Rev Neurosci 22: 567-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliades SJ, Wang X (2003) Sensory-motor interaction in the primate auditory cortex during self-initiated vocalizations. J Neurophysiol 89: 2194-2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman JL (1981) Effects of frequency-shifted feedback on the pitch of vocal productions. J Acoust Soc Am 70: 45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel KM, Nudo RJ (1998) Recovery of motor function after focal cortical injury in primates: compensatory movement patterns used during rehabilitative training. Somatosens Mot Res 15: 173-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracco VL (1994) Some organizational characteristics of speech movement control. J Speech Hear Res 37: 4-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P (1997) Auditory onset responses revisited. I. First-spike timing. J Neurophysiol 77: 2616-2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P, Irvine DR (1997) First-spike timing of auditory-nerve fibers and comparison with auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 78: 2438-2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein R, Held A (1963) Movement-produced stimulation in the development of visually guided behavior. J Comp Physiol Psychol 56: 872-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde JF (1997) Sensorimotor adaptation in speech production. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Houde JF, Jordan MI (1997) Adaptation in speech motor control. Paper presented at 11th Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Denver, CO, December.

- Houde JF, Jordan MI (1998) Sensorimotor adaptation in speech production. Science 279: 1213-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde JF, Jordan MI (2002) Sensorimotor adaptation of speech I: compensation and adaptation. J Speech Lang Hear Res 45: 295-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi K, Priebe NJ, Crum PA, Bedenbaugh PH, Cheung SW, Schreiner CE (2004) Modular functional organization of cat anterior field. J Neurophysiol 92: 444-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JA, Munhall KG (2000) Perceptual calibration of F0 production: evidence from feedback perturbation. J Acoust Soc Am 108: 1246-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JA, Munhall KG (2003) Learning to produce speech with an altered vocal track: the role for auditory feedback. J Acoust Soc Am 113: 532-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens U (1998) Neuronal control of mammalian vocalization, with special reference to the squirrel monkey. Naturwissenschaften 85: 376-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens U (2000) Localization of a pontine vocalization-controlling area. J Acoust Soc Am 108: 1393-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens U (2002) Neural pathways underlying vocal control. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 26: 235-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens U, Lu CL (1993) The effects of periaqueductally injected transmitter antagonists on forebrain-elicited vocalization in the squirrel monkey. Eur J Neurosci 5: 735-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgard MP, Merzenich MM (1998a) Cortical map reorganization enabled by nucleus basalis activity. Science 279: 1714-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgard MP, Merzenich MM (1998b) Plasticity of temporal information processing in the primary auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci 1: 727-731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgard MP, Pandya PK, Vazquez J, Gehi A, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM (2001) Sensory input directs spatial and temporal plasticity in primary auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 86: 326-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M (1965) The role of auditory feedback in the control of vocalization in the white-crowned sparrow. Z Tierpsychol 22: 770-783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane H, Wozniak J, Matthies M, Svirsky M, Perkell J, O'Connell M, Manzella J (1997) Changes in sound pressure and fundamental frequency contours following changes in hearing status. J Acoust Soc Am 101: 2244-2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardo A, Konishi M (1999) Decrystallization of adult birdsong by perturbation of auditory feedback. Nature 399: 466-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardino AJ, Nottebohm F (2000) Age at deafening affects the stability of learned song in adult male zebrafinches. J Neurosci 20: 5054-5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marler P, Sherman V (1983) Song structure without auditory feedback: emendations of the auditory template hypothesis. J Neurosci 3: 517-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthies ML, Svirsky M, Perkell J, Lane H (1996) Acoustic and articulatory measures of sibilant production with and without auditory feedback from a cochlear implant. J Speech Hear Res 39: 936-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCasland JS (1987) Neuronal control of bird song production. J Neurosci 7: 23-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson JR, Schreiner CE, Sutter ML (1997) Functional topography of cat primary auditory cortex, response latencies. J Comp Physiol [A] 181: 615-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mioche L, Singer W (1989) Chronic recordings from single sites of kitten striate cortex during experience-dependent modifications of receptive-field properties. J Neurophysiol 62: 185-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Preuss P, Ploog D (1981) Inhibition of auditory cortical neurons during phonation. Brain Res 215: 61-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan SS, Cheung SW, Bedenbaugh P, Beitel RE, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM (2002) Representation of spectral and temporal envelope of twitter vocalizations in common marmoset primary auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 87: 1723-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordeen KW, Nordeen EJ (1992) Auditory feedback is necessary for the maintenance of stereotyped song in adult zebra finches. Behav Neural Biol 57: 58-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudo RJ (1997) Remodeling of cortical motor representations after stroke: implications forrecovery from brain damage. Mol Psychiatry 2: 188-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce JM, Hall G (1980) A model for pavlovian learning: variations in the effectiveness of conditioned but not of unconditioned stimuli. Psychol Rev 87: 532-552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plautz EJ, Milliken GW, Nudo RJ (2000) Effects of repetitive motor training on movement representations in adult squirrel monkeys: role of use versus learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem 74: 27-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploog D (1981) Neurobiology of primate audio-vocal behavior. Brain Res 228: 35-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan R (2001) Plasticity of excitation and inhibition in the receptive field of primary auditory cortical neurons after limited receptor organ damage. Cereb Cortex 11: 171-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recanzone GH, Merzenich MM, Schreiner CE (1992) Changes in the distributed temporal response properties of SI cortical neurons reflect improvements in performance on a temporally based tactile discrimination task. J Neurophysiol 67: 1071-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recanzone GH, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM (1993) Plasticity in the frequency representation of primary auditory cortex following discrimination training in adult owl monkeys. J Neurosci 13: 87-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recanzone GH, Schreiner CE, Sutter ML, Beitel RE, Merzenich MM (1999) Functional organization of spectral receptive fields in the primary auditory cortex of the owl monkey. J Comp Neurol 415: 460-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, Solomon RL (1967) Two-process learning theory: relationships between pavlovian conditioning and instrumental learning. Psychol Rev 74: 151-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D, Irvine DR (1989) Plasticity of frequency organization in auditory cortex of guinea pigs with partial unilateral deafness. J Comp Neurol 282: 456-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieber MH, Deuel RK (1997) Primary motor cortex reorganization in a long-term monkey amputee. Somatosens Mot Res 14: 157-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner CE (1998) Spatial distribution of responses to simple and complex sounds in the primary auditory cortex. Audiol Neurootol 3: 104-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner CE, Mendelson JR (1990) Functional topography of cat primary auditory cortex, distribution of integrated excitation. J Neurophysiol 64: 1442-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiden HR (1957) Auditory acuity of the marmoset monkeys (Hapale jacchus). PhD thesis, Princeton University.

- Solis MM, Doupe AJ (1999) Contributions of tutor and bird's own song experience to neural selectivity in the songbird anterior forebrain. J Neurosci 19: 4559-4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis MM, Doupe AJ (2000) Compromised neural selectivity for song in birds with impaired sensorimotor learning. Neuron 25: 109-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis MM, Brainard MS, Hessler NA, Doupe AJ (2000) Song selectivity and sensorimotor signals in vocal learning and production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 11836-11842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter ML, Schreiner CE (1991) Physiology and topography of neurons with multipeaked tuning curves in cat primary auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 65: 1207-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter ML, Schreiner CE (1995) Topography of intensity tuning in cat primary auditory cortex: single-neuron versus multiple-neuron recordings. J Neurophysiol 73: 190-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson DJ (1982) Spectrum estimation and harmonic analysis. Proc IEEE 70: 1055-1096. [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg JT, Chen BE, Knott GW, Feng G, Sanes JR, Welker E, Svoboda K (2002) Long-term in vivo imaging of experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in adult cortex. Nature 420: 788-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldstein RS (1990) Effects of postlingual deafness on speech production: implications for the role of auditory feedback. J Acoust Soc Am 88: 2099-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Merzenich MM, Beitel R, Schreiner CE (1995) Representation of a species-specific vocalization in the primary auditory cortex of the common marmoset: temporal and spectral characteristics. J Neurophysiol 74: 2685-2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM (1995) Dynamic regulation of receptive fields and maps in the adult sensory cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 18: 129-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM (1998) Physiological memory in primary auditory cortex: characteristics and mechanisms. Neurobiol Learn Mem 70: 226-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesel TN, Hubel DH (1965) Comparison of the effects of unilateral and bilateral eye closure on cortical unit responses in kittens. J Neurophysiol 28: 1029-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LI, Bao S, Merzenich MM (2001) Persistent and specific influences of early acoustic environments on primary auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci 4: 1123-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LI, Bao S, Merzenich MM (2002) Disruption of primary auditory cortex by synchronous auditory inputs during a critical period. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 2309-2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]