Significance

The lactose permease from Escherichia coli (LacY), a model for the major facilitator superfamily, catalyzes the symport of a galactopyranoside and an H+ across the membrane by a mechanism in which the sugar-binding site in the middle of the protein becomes alternately accessible to either side of the membrane. The global conformational change is dissected into events that occur on the cytoplasmic and periplasmic aspects of LacY. Rates of individual steps are measured directly during opening or closing of periplasmic or cytoplasmic cavities by utilizing changes in Trp-bimane fluorescence with LacY in a phospholipid membrane. The findings provide a better understanding of the alternating access mechanism.

Keywords: membrane transport proteins, major facilitator superfamily

Abstract

Galactoside/H+ symport across the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli is catalyzed by lactose permease (LacY), which uses an alternating access mechanism with opening and closing of deep cavities on the periplasmic and cytoplasmic sides. In this study, conformational changes in LacY initiated by galactoside binding were monitored in real time by Trp quenching/unquenching of bimane, a small fluorophore covalently attached to the protein. Rates of change in bimane fluorescence on either side of LacY were measured by stopped flow with LacY in detergent or in proteoliposomes and were compared with rates of galactoside binding. With LacY in proteoliposomes, the periplasmic cavity is tightly sealed and the substrate-binding rate is limited by the rate of opening of this cavity. Rates of opening, measured as unquenching of bimane fluorescence, are 20–30 s−1, independent of sugar concentration and essentially the same in detergent or in proteoliposomes. On the cytoplasmic side of LacY in proteoliposomes, slow bimane quenching (i.e., closing of the cavity) is observed at a rate that is also independent of sugar concentration and similar to the rate of sugar binding from the periplasmic side. Therefore, opening of the periplasmic cavity not only limits access of sugar to the binding site of LacY but also controls the rate of closing of the cytoplasmic cavity.

Although documented extensively with the lactose permease from Escherichia coli (LacY) only (reviewed in refs. 1, 2), alternating access is now generally accepted as the overall mechanism of transport for many membrane transport proteins. LacY, a member of the major facilitated superfamily (3), catalyzes the coupled stoichiometric transport of an H+ and a galactopyranoside (galactoside/H+ symport) across the cytoplasmic membrane (reviewed in ref. 4). With an abundance of biochemical, spectroscopic, and crystallographic data regarding structure and function, LacY is arguably the most extensively studied symport protein at the present time (reviewed in ref. 5).

LacY is organized into two pseudosymmetrical bundles, each containing six transmembrane helices, most of which are irregular, with the N and C termini on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. WT LacY and a conformationally restricted mutant exhibit an inward-facing conformation with a tightly sealed periplasmic side and a water-filled cavity open to the cytoplasm (6–9), which is the conformation present in the membrane in the absence of sugar (10). Another conformation has been observed recently with a double-Trp mutant (11) that exhibits an occluded galactoside molecule with a narrow opening on the periplasmic side and a tightly sealed cytoplasmic aspect (12) (Fig. 1A).

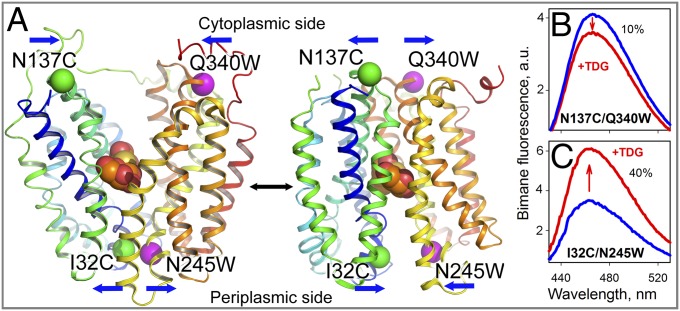

Fig. 1.

Detection of conformational changes in LacY by Trp quenching of bimane fluorescence. (A) Side view of LacY with cytoplasmic- or periplasmic-open cavities [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 2CFQ (Left) and PDB ID code 4OAA (Right)]. Transmembrane helices are rainbow-colored from blue (helix I) to red (helix XII), and a bound galactoside (orange spheres) is shown at the apex of the cavities. Pairs of Cys-Trp replacements introduced individually on opposite sides of the periplasmic or cytoplasmic cavities are shown with the indicated positions of Cα atoms of Trp (pink spheres) and PDT-bimane–labeled Cys (green spheres) residues. Blue arrows show the direction of movement. (B) Quenching of bimane fluorescence on the cytoplasmic side of LacY observed with bimane-labeled N137C/Q340W mutant. a.u., arbitrary units. (C) Unquenching of bimane fluorescence on the periplasmic side of LacY observed with bimane-labeled I32C/N245W mutant. Blue and red lines represent bimane emission spectra before and after addition of 10 mM TDG, respectively. Spectra were recorded with excitation at 380 nm with 0.3 μM protein in 50 mM NaPi/0.02% DDM (pH 7.5).

LacY is highly dynamic and exhibits multiple conformations at any given time, and galactoside binding triggers a shift between conformers (1). Thus, measurement of interspin distances with nitroxide-labeled Cys pairs in LacY reveals that sugar binding induces a decrease in distances on the cytoplasmic side and a corresponding increase in distances on the periplasmic side (13, 14). Site-directed alkylation of single Cys LacY mutants in either right-side-out membrane vesicles (15, 16) or dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM) micelles (10), as well as single-molecule fluorescence (17) and thiol cross-linking (18), also indicates that sugar binding increases the probability of opening on the periplasmic side and closing on the cytoplasmic side.

Recently, conformational changes in LacY have been studied dynamically by site-directed Trp fluorescence quenching by a protonated His or Lys residue (19). Sugar binding leads to unquenching of Trp fluorescence in periplasmic LacY mutants N245W (helix VII) or F378W (helix XII) due to increased distance from native quenchers His35 (helix I) or Lys42 (helix II), respectively, findings consistent with opening of the periplasmic cavity. Rates of unquenching of Trp measured in DDM by stopped flow for both mutants reveal rapid opening of the periplasmic cavity. In contrast, on the cytoplasmic side, slow quenching of Trp140 (helix V) by His334 (helix X) is observed with double-mutant F140W/F334H, which indicates closing of the cytoplasmic cavity.

In proteoliposomes, sugar-binding rates measured directly for mutant N245W with 4-nitrophenyl-α-d-galactopyranoside (NPG) by Trp151→NPG FRET are independent of sugar concentration and very similar (56 s−1) to rates of opening of the periplasmic cavity measured in DDM micelles (50–100 s−1) by Trp unquenching as described above. Thus, opening of the periplasmic cavity is limiting for access to the galactoside-binding site with LacY reconstituted into proteoliposomes (20). However, utilization of Trp fluorescence quenching to measure rates of conformational change in proteoliposomes is challenging because of low signal amplitude. Therefore, the small fluorescence probe bimane, which is comparable in size to Trp, was selected to increase the signal-to-noise ratio for measurements in proteoliposomes. Labeling of Cys residues with (2-pyridyl)dithiobimane (PDT-bimane) generates a fluorescence probe with a short disulfide linker that is cleavable by thiol reagents, such as Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), and reports short-range interactions in proteins by Trp-induced bimane quenching (21, 22). The efficiency of bimane quenching is dependent upon proximity to Trp as well as other factors, such as stereochemistry and local environment. The magnitude of bimane quenching by Trp in membrane proteins is typically a 10–50% change in the emission spectra, as reported with visual rhodopsin (23, 24), the cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel (25), or the β-adrenoreceptor (26).

In this paper, mutants were constructed with Trp-Cys pairs in regions of LacY where movements are predicted due to conformational changes. Mutant proteins were then purified, labeled with PDT-bimane, and examined for Trp quenching of bimane fluorescence. The majority of the mutants exhibit phenomena that are entirely consistent with the alternating access mechanism. Two PDT-bimane–labeled mutants that have sugar-binding kinetics typical of WT LacY were used for stopped-flow measurements of rates of conformational change on either the periplasmic or cytoplasmic side of LacY reconstituted into proteoliposomes. The findings demonstrate that the rate of opening of the periplasmic cavity is limiting for sugar binding to reconstituted LacY and also defines the rate of closing of the cytoplasmic cavity.

Results

Effect of Galactoside Binding on Bimane Fluorescence.

Closing or opening of cytoplasmic or periplasmic cavities, respectively, in LacY was examined initially by galactoside-induced Trp-bimane quenching or unquenching in steady-state fluorescence experiments (21) with various PDT-bimane–labeled mutants containing Cys-Trp pairs. Cys137 (helix IV) and Trp340 (helix X) were placed on opposing sides of the cytoplasmic cavity in N137C/Q340W LacY (Fig. 1A). The PDT-bimane–labeled mutant exhibits a decrease in fluorescence upon binding of β-d-galactopyranosyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (TDG), indicating closing of the cavity (Fig. 1B). In contrast, on the periplasmic aspect, PDT-bimane–labeled mutant I32C/N245W exhibits an increase in fluorescence upon TDG binding (Fig. 1C), indicating opening of the periplasmic cavity and increasing distance between Cys32 (helix I) and Trp245 (helix VII). With both paired mutants, the change in bimane fluorescence is not associated with a spectral shift of the emission maximum, suggesting that there is no change in polarity around fluorophore. Similar effects of TDG binding, quenching on the cytoplasmic side and unquenching on the periplasmic side, are seen with several additional cytoplasmic and periplasmic bimane-Trp pairs (Fig. S1). The observations confirm and extend previous findings with Trp as a fluorescent probe as described above (19).

The change in bimane fluorescence with each mutant does not exceed 40%, and the relatively small effects are most likely associated with high flexibility of LacY and the presence of multiple conformers (13). The extent of bimane quenching by an engineered Trp residue also depends on possible background quenching by native amino acyl side chains (mostly Trp and Tyr). Therefore, TCEP reduction experiments were carried out in the absence of sugar to test the proximity between bimane and quenchers in each mutant. TCEP reduction of the S-S bond between bimane and Cys releases the fluorophore and markedly increases fluorescence if a quencher is in close proximity to the attached bimane (21). Indeed, when a PDT-bimane–labeled Cys residue is on the periplasmic side of LacY in the absence of the Trp replacement, TCEP reduction does not significantly alter bimane emission (Fig. S2 A and C). However, introduction of Trp on the opposing six-helix bundle results in a dramatic increase in bimane fluorescence after TCEP reduction, indicating that the engineered Trp residue is primarily responsible for bimane quenching (compare Fig. S2 A and B, C and D, and E and F) and consistent with tight packing on the periplasmic side. On the cytoplasmic side, an introduced Trp residue has little or no influence on bimane fluorescence in Cys-Trp pairs (compare Fig. S2 G and H, I and J, and K and L). Thus, the cytoplasmic cavity is open, and distances between Trp and bimane are too great to cause quenching of the latter (21). Notably, several Cys mutants labeled with bimane and devoid of introduced Trp exhibit significant bimane quenching by native side chains (Fig. S2 E, I, and K). In these mutants, the conformational changes triggered by galactoside binding yield relatively small quenching/unquenching of bimane fluorescence by the Trp residue inserted.

Sugar Binding to PDT-Bimane–Labeled Mutants.

Galactoside binding and conformational rearrangements are interrelated in LacY; thus, it is important that mutants constructed for studying conformational changes exhibit sugar-binding kinetics similar to those of WT LacY. Therefore, sugar binding by bimane-labeled mutants was examined with NPG, a galactoside that participates in Trp151→NPG FRET (27) (Fig. S3A). In addition, NPG triggers bimane quenching/unquenching by an engineered Trp residue (Fig. S3B), as observed with other galactosides (Fig. 1 B and C and Fig. S3C). Moreover, the kinetic parameters of NPG binding (20) are not altered by replacement of highly reactive Cys148 with Met (C148M) (Fig. S4), which is important because the C148M replacement was included to prevent unwanted labeling in the mutants.

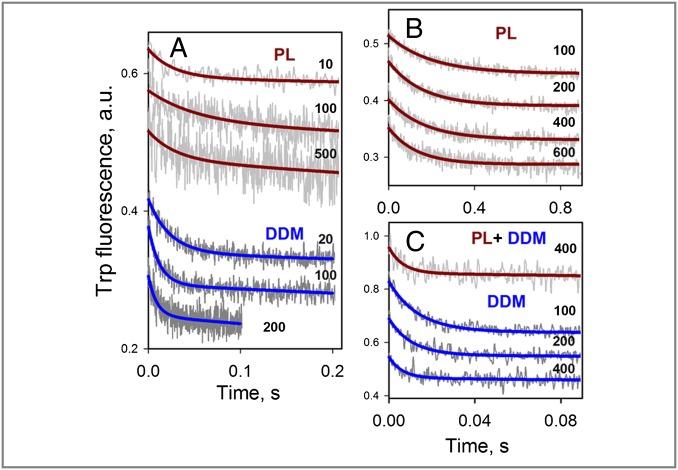

Both bimane-labeled Cys-Trp mutants shown in Fig. 1 display NPG-binding affinities similar to WT LacY, as measured by stopped flow in displacement experiments allowing estimation of the displacement or “off rate” (koff) and Kd for sugar binding (Fig. 2). Kd values for bimane-labeled I32C/N245W and N137C/Q340W in DDM micelles are 9 and 37 μM, respectively, and 6 and 17 μM, respectively, in proteoliposomes, whereas Kd values for WT LacY are 28 μM in DDM and 11 μM in proteoliposomes (Fig. S4A). NPG koff values are also comparable for the mutants and WT LacY when measured either in DDM or in reconstituted proteoliposomes (Fig. S5). Furthermore, as described for WT LacY (20), NPG-binding rates measured directly with the PDT-bimane–labeled mutant I32C/N245W or N137C/Q340W in DDM micelles increase with NPG concentration (Fig. 3, blue lines), whereas in proteoliposomes, binding rates are independent of NPG concentration (Fig. 3 A and B, brown lines). Therefore, both mutants exhibit sugar-binding kinetics similar to those of WT LacY, indicating that after bimane labeling of Cys-Trp mutants, the LacY molecules remain reasonably undisturbed.

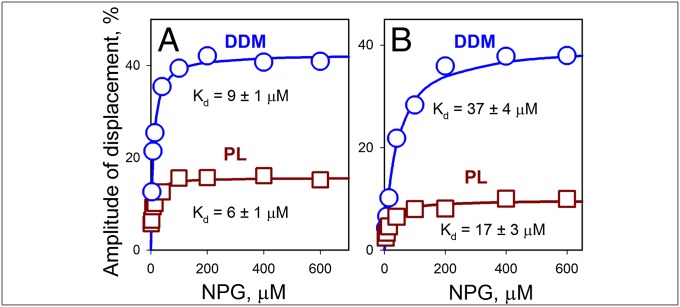

Fig. 2.

Sugar binding to bimane-labeled LacY mutants. NPG-binding affinity was measured with periplasmic mutant I32C/N245W (A) and cytoplasmic mutant N137C/Q340W (B) in displacement experiments with proteins dissolved in DDM (○) or reconstituted into proteoliposomes (PL; □). Stopped-flow traces were recorded after mixing a saturating concentration of TDG (15 mM) with protein preincubated with the indicated concentrations of NPG (Fig. S5). The amplitude of Trp fluorescence change is expressed as a percentage of the final fluorescence level of the individual stopped-flow trace. Kd values estimated from hyperbolic fits of concentration dependencies of displacement amplitudes are given. Average values of koff calculated with mutant I32C/N245W from individual experiments at nine NPG concentrations are 17 ± 1 s−1 and 25 ± 2 s−1 in DDM and PL, respectively. For mutant N137C/Q340W, koff values calculated from experiments at eight NPG concentrations are 50 ± 3 s−1 and 69 ± 15 s−1 in DDM and PL, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Rates of NPG binding measured directly for bimane-labeled mutants of LacY. (A) Stopped-flow traces of Trp fluorescence changes are recorded after mixing of NPG with periplasmic mutant I32C/N245W solubilized in DDM (Lower) or reconstituted into PL (Upper), with single-exponential fits shown as blue and brown lines, respectively. Micromolar concentrations of NPG are indicated. (B) Stopped-flow traces recorded after mixing of indicated concentrations of NPG with cytoplasmic mutant N137C/Q340W reconstituted into PL. Single-exponential fits are shown as brown lines. (C) Stopped-flow traces recorded after mixing of indicated concentrations of NPG with mutant N137C/Q340W in DDM micelles (Lower) or after dissolving the PL in DDM. Single-exponential fits are shown as solid lines. Note the different time scales in B and C. Kinetic parameters of sugar binding estimated from concentration dependences are presented in Figs. 6A and 7A.

Rates of Opening and Closing of the Periplasmic Cavity.

Use of NPG allows simultaneous determination of sugar-binding rates and rates of conformational change by measuring Trp151→NPG FRET and bimane fluorescence changes, respectively. Stopped-flow traces recorded after mixing NPG with bimane-labeled I32C/N245W mutant solubilized in DDM exhibit a rapid decrease in Trp fluorescence [Fig. 4A, green trace; observed rate (kobs) = 112 s−1] and a much slower increase in bimane fluorescence (Fig. 4A, gray trace; kobs = 26 s−1). The data indicate that rapid saturation of the sugar-binding site accessible from the cytoplasmic side (Kd = 9 μM; Fig. 2A) triggers a slow shift to a conformer with an open periplasmic cavity, which is detected by bimane unquenching.

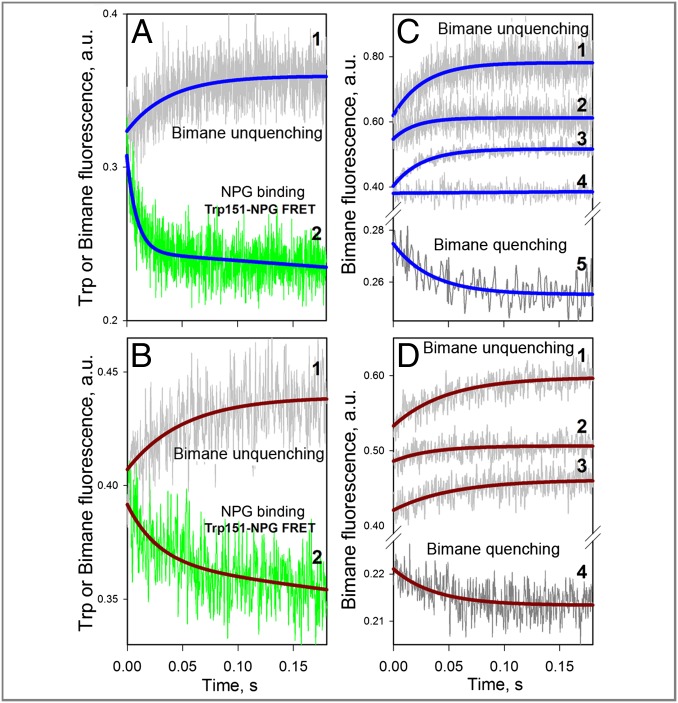

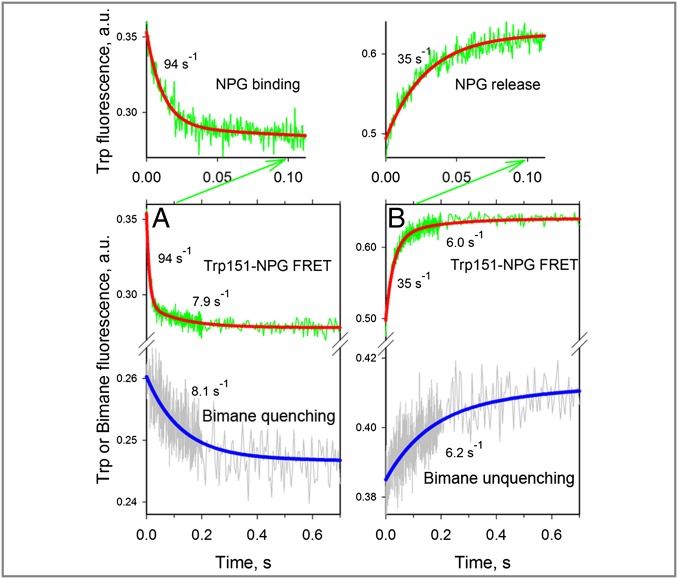

Fig. 4.

Rates of opening and closing of the periplasmic cavity measured with bimane-labeled I32C/N245W mutant. (A) Comparison of the NPG-binding rate (Trp151→NPG FRET) with the rate of bimane unquenching for LacY in DDM micelles. Stopped-flow traces after mixing protein with 0.2 mM NPG were recorded simultaneously with excitation at 295 nm, with collection of emitted light from bimane (trace 1, gray) and Trp (trace 2, green) using two photomultipliers. (B) Same approach as described in A was used for protein reconstituted into proteoliposomes. Traces 1 and 2 show fluorescence change of bimane and Trp, respectively, after mixing proteoliposomes with 0.2 mM NPG. (C) Stopped-flow traces of bimane fluorescence recorded with excitation at 380 nm in DDM. Traces 1, 2, 3, and 4 represent mixing protein with 0.2 mM NPG, 20 mM lactose, 10 mM TDG, and 10 mM sucrose, respectively. Trace 5 was recorded after mixing 25 μL of protein containing 40 μM NPG with 250 μL of buffer. (D) Stopped-flow traces of bimane fluorescence recorded with excitation at 380 nm for protein reconstituted into proteoliposomes. Traces 1, 2, and 3 show the effect of 0.2 mM NPG, 20 mM lactose, and 10 mM TDG, respectively. Trace 4 was recorded after 10-fold dilution of protein premixed with 30 μM NPG. Single-exponential fits are shown as blue and brown lines for experiments with protein in DDM micelles or reconstituted into proteoliposomes, respectively. Estimated rates are given in the main text.

Remarkably, a similar experiment with the same mutant reconstituted into proteoliposomes (Fig. 4B) shows practically identical rates of Trp and bimane fluorescence changes (kobs = 28 ± 7 s−1), indicating that binding of sugar occurs only after the periplasmic cavity opens. Approximately the same rate of unquenching is observed when the conformational change is detected by bimane fluorescence specifically (excitation at 380 nm). Binding of NPG, lactose, or TDG either in DDM micelles or after reconstitution into proteoliposomes results in slow unquenching of bimane fluorescence with kobs = 33 ± 11 s−1 (Fig. 4 C and D, traces 1, 2, and 3). However, sucrose, which is not a substrate of LacY, has no effect on bimane fluorescence (Fig. 4C, trace 4). Notably, when the mutant is preincubated with NPG and then rapidly diluted into buffer, slow bimane quenching is observed (kobs = 27 ± 3 s−1 in both DDM and proteoliposomes) as a result of closing of the periplasmic cavity after sugar release (Fig. 4C, trace 5, and Fig. 4D, trace 4).

Another bimane-labeled periplasmic mutant, K42C/F378W, also exhibits a slow rate of bimane unquenching after binding TDG in DDM micelles (Fig. S6A, trace 3; kobs = 38 s−1), although the small amplitude of the effect does not allow accurate measurement when the mutant protein is reconstituted into proteoliposomes (Fig. S6B, trace 3).

Rates of Opening and Closing of the Cytoplasmic Cavity.

Simultaneous measurements of the rate of NPG binding and the rate of conformational change were also carried out with PDT-bimane–labeled N137C/Q340W mutant (Fig. 1). Stopped-flow traces recorded after mixing of NPG with the mutant in DDM micelles show a decrease in Trp (Fig. 5A, Trp151→NPG FRET, green trace), as well as bimane fluorescence (Fig. 5A, gray trace), consistent with rapid sugar binding from the cytoplasmic side and slower closure of the cytoplasmic cavity. A double-exponential fit of the Trp fluorescence change (Fig. 5A, red line) allows determination of a major process with large amplitude and a fast rate (Fig. 5A; kobs = 94 s−1) and a much slower process (Fig. 5A; kobs = 7.9 s−1) with small amplitude. Remarkably, the rate of the slower component is identical to the rate of conformational change detected by bimane quenching (Fig. 5A, blue line; kobs = 8.1 s−1). Therefore, the slower rate detected by Trp fluorescence likely reflects the same conformational change initiated by sugar binding as reported by bimane quenching.

Fig. 5.

Rates of opening and closing of the cytoplasmic cavity measured in DDM with bimane-labeled mutant N137C/Q340W. All traces were recorded with excitation at 295 nm, and emitted light was collected as described in Fig. 4A using two photomultipliers for simultaneous detection of Trp151→NPG FRET (NPG binding or release) and bimane fluorescence (closing or opening of the cytoplasmic cavity). (A) Mixing protein with 0.2 mM NPG results in quenching of bimane fluorescence (Lower, gray trace) and a decrease of Trp fluorescence (Lower, green trace), with the initial part of the trace (0.1-s scale, green arrow) expanded (Upper). A single-exponential fit of bimane fluorescence change (Lower, blue line) allows estimation of the rate of cavity closure (kobs = 8.1 s−1). The decrease in Trp fluorescence is fitted with a double-exponential equation (red line), which allowed estimation of the NPG-binding rate (kobs = 94 s−1), followed by a much smaller decrease in amplitude with kobs = 7.9 s−1. (B) Dilution of 25 μL of protein containing 0.2 mM NPG by mixing with 250 μL of buffer results in unquenching of bimane fluorescence (Lower, gray trace) and an increase in Trp fluorescence (Lower, green trace), with the initial portion of the trace (0.1-s scale, green arrow) expanded (Upper). A single-exponential fit of the bimane fluorescence change (Lower, blue line) allows estimation of the rate of cavity opening (kobs = 6.2 s−1). The increase in Trp fluorescence is fitted with a double-exponential equation (red line), which allowed an estimate of the rate of NPG release (kobs = 35 s−1), followed by a much smaller increase in amplitude with kobs = 6.0 s−1.

When the same mutant is preincubated with 0.2 mM NPG and then diluted into solution devoid of sugar, the opposite process is observed: release of NPG and opening of the cytoplasmic cavity (Fig. 5B). Thus, simultaneously recorded stopped-flow traces demonstrate an increase in both Trp fluorescence (Fig. 5B, Trp151→NPG FRET, green trace) and bimane fluorescence (Fig. 5B, gray trace). A double-exponential fit of the change in Trp fluorescence (Fig. 5B, red line) resolves a major process with higher amplitude and a faster rate (Fig. 5B; kobs = 35 s−1) and a slower process (Fig. 5B; kobs = 6.0 s−1) with lower amplitude. A single-exponential fit of the unquenching of bimane fluorescence (Fig. 5B, blue line; kobs = 6.2 s−1) demonstrates practically the same rate as the slower component observed by Trp fluorescence. Rapid dissociation of sugar occurs via an open periplasmic cavity and leads to a slower conformational shift toward the structure with an open cytoplasmic cavity.

Comparison of the rates of bimane quenching and unquenching (Fig. 5 A and B, Lower) indicates that the cytoplasmic cavity opens and closes with the same rates. Similar rates of conformational change (kobs = 3.5–4.2 s−1) were determined by bimane fluorescence specifically (excitation at 380 nm) for mutant N137C/Q340W in DDM micelles (Fig. S7 A and B) or reconstituted into proteoliposomes (Fig. S7C).

Rates of Sugar Binding and Conformational Change.

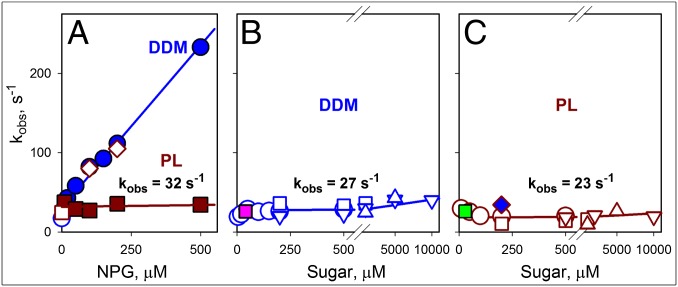

Concentration dependencies of sugar-binding rates and rates of conformational change measured with bimane-labeled mutants are presented in Fig. 6 (I32C/N245W) and Fig. 7 (N137C/Q340W). Binding of NPG to both mutants in DDM micelles is remarkably similar to that observed with WT LacY [Fig. S4B, blue lines, “on rate” (kon) = 0.2 μM−1⋅s−1], exhibiting linear dependence of observed rates on sugar concentration with a kon estimated as 0.3–0.4 μM−1⋅s−1 (Figs. 6A and 7A, blue lines). After reconstitution into proteoliposomes, both mutants display sugar-binding rates that are independent of NPG concentration with kobs = 32 ± 5 s−1 for periplasmic mutant I32C/N245W and kobs = 6 ± 1 s−1 for cytoplasmic mutant N137C/Q340W (Figs. 6A and 7A, brown lines), which are comparable to the rate measured for WT LacY (Fig. S4B, brown line, kobs = 21 ± 4 s−1).

Fig. 6.

Rates of sugar binding and opening of the periplasmic cavity. The data shown were obtained for bimane-labeled I32C/N245W LacY from the stopped-flow measurements described in Figs. 3A and 4 and Fig. S6. (A) Concentration dependencies of NPG-binding rates (kobs) were measured by Trp151→NPG FRET with protein solubilized in DDM (blue ●), reconstituted into PL (brown ■), or after dissolving the PL in DDM (◇). Displacement rates (koff) for protein in DDM micelles (○) or PL (□) are shown. Kinetic parameters for NPG binding in DDM are kon = 0.4 μM−1⋅s−1 and koff = 30 s−1. Reconstituted protein binds sugar with kobs = 32 ± 5 s−1. (B) Rates of change in bimane fluorescence measured with protein solubilized in DDM are plotted against NPG concentration (○ and □ correspond to excitation at 295 and 380 nm, respectively) and TDG or lactose (▽ and △, respectively, excitation at 380 nm). The pink ■ corresponds to the rate of bimane quenching after dilution of protein preincubated with NPG. The estimated rate of opening/closing of the periplasmic cavity in DDM is 27 ± 5 s−1. (C) Rates of bimane fluorescence unquenching for protein reconstituted into PL are plotted vs. the concentration of NPG (○ and □ correspond to excitation at 295 and 380 nm, respectively) and TDG, or lactose (▽ and △, respectively, excitation at 380 nm). The green ■ corresponds to the rate of bimane quenching after dilution of protein preincubated with NPG. The blue ◆ corresponds to the rate of bimane unquenching after dissolving the PL in DDM. The estimated rate of opening/closing of the periplasmic cavity for the reconstituted protein is 23 ± 7 s−1.

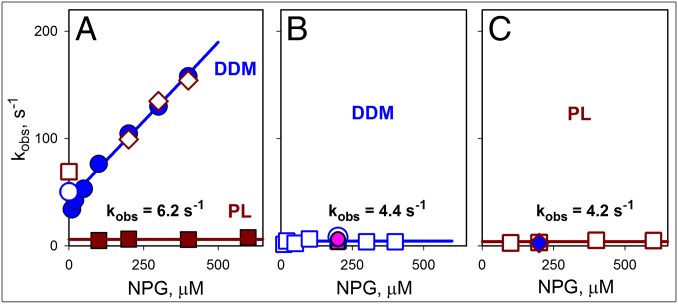

Fig. 7.

Rates of sugar binding and closing of the cytoplasmic cavity. The data shown were obtained for bimane-labeled N137C/Q340W LacY from the stopped-flow measurements described in Figs. 3 B and C and 5 and Fig. S7. (A) Concentration dependence of NPG-binding rates (kobs) measured by Trp151→NPG FRET with protein solubilized in DDM (blue ●), reconstituted into PL (brown ■), or after dissolving the PL in DDM (◇). The koff values for protein in DDM micelles (○) or PL (□) are shown. Kinetic parameters for NPG binding in DDM are kon = 0.3 μM−1⋅s−1 and koff = 43 s−1. Reconstituted protein binds sugar with kobs = 6.2 ± 1.1 s−1. (B) Rates of bimane fluorescence change measured in DDM after mixing protein with NPG (○ and □ with excitation at 295 nm and 380 nm, respectively) or after dilution of protein preincubated with NPG (pink ● and ■ for measurements with excitation at 295 and 380 nm, respectively). The estimated rate of opening/closing of the cytoplasmic cavity in DDM is 4.4 ± 2.0 s−1. (C) Rates of bimane quenching measured after mixing of NPG with protein reconstituted into PL (□, excitation at 380 nm) or with the same PL dissolved in DDM (blue ◆). The estimated rate of cytoplasmic cavity closing for the reconstituted protein is 4.2 ± 1.3 s−1.

Rates of conformational change on the periplasmic or cytoplasmic side of bimane-labeled mutants as a function of sugar concentration are presented in Figs. 6 B and C and 7 B and C. With periplasmic mutant I32C/N245W, bimane quenching/unquenching rates in DDM display no dependence on sugar concentration and are similar for NPG, TDG, and lactose, with an estimated kobs = 27 ± 5 s−1 (Fig. 6B). The same rate is observed for this mutant after reconstitution into proteoliposomes (kobs = 23 ± 7 s−1) with the three galactosides (Fig. 6C). Thus, LacY embedded in a phospholipid membrane exhibits the same rates of opening/closing of the periplasmic cavity as observed in DDM. Moreover, the rate of conformational change on the periplasmic side is indistinguishable from the rate of sugar binding to the LacY reconstituted into proteoliposomes (compare brown line in Fig. 6A with data in Fig. 6 B and C), indicating that opening of the periplasmic cavity limits the rate of sugar binding to reconstituted LacY.

With the cytoplasmic mutant N137C/Q340W, rates of conformational change measured in DDM and in proteoliposomes are similar (kobs = 4.2–4.4 s−1) and independent of sugar concentration (Fig. 7 B and C). The observed rates are similar to sugar-binding rates measured directly by Trp151→NPG FRET with the mutant reconstituted into proteoliposomes (Fig. 7A, brown line). The slow rate of sugar binding with the reconstituted mutant N137C/Q340W is likely due to slow opening of the periplasmic cavity. Hence, opening and closing of the cytoplasmic cavity occurs with similar slow rates in DDM and proteoliposomes.

Slow opening of the periplasmic cavity is also observed with another cytoplasmic Cys-Trp mutant, F140W/V343C, labeled with bimane (Fig. S8). Fast NPG-binding rates are observed in DDM that are linearly dependent on ligand concentration (kon = 0.8 μM−1⋅s−1), with slow binding in proteoliposomes (kobs = 6 s−1 for all tested NPG concentrations). The conformational change reported by bimane quenching is fast in DDM (maximum kobs = 200 s−1) and slow in proteoliposomes (kobs = 5 s−1). Clearly, with the mutant reconstituted into proteoliposomes, the periplasmic cavity opens slowly. This slow process limits the rate of sugar binding, which subsequently defines the rate of closing on the cytoplasmic side as observed with bimane quenching (compare brown lines in Fig. S8 D and F).

Discussion

Distance-dependent quenching of bimane fluorescence by Trp is used here to study global conformational changes in LacY resulting from sugar binding to the symporter solubilized in DDM or reconstituted into proteoliposomes. Sugar-induced opening or closing of the periplasmic and cytoplasmic cavities, respectively, is confirmed by bimane fluorescence unquenching and quenching, which provides a stronger signal than the previous method (20), and the findings provide further support for the alternating access mechanism (reviewed in refs. 1 and 2).

Notably, TCEP reduction confirms that without bound sugar, LacY exists mainly in an inward-facing conformation closed on the periplasmic side, a conclusion derived from the spectra of PDT-bimane–labeled samples before and after reduction, which reveal that Trp residues effectively quench bimane in periplasmic pairs but do not affect fluorescence in cytoplasmic pairs. Also, TCEP reduction demonstrates that in several mutants, background quenching of bimane occurs without the introduced Trp, which results in an apparent decrease in Trp quenching with these engineered Cys-Trp pairs. Nevertheless, Trp-induced bimane fluorescence changes in response to sugar binding are suitable for stopped-flow measurements of conformational changes in LacY in DDM micelles or in reconstituted proteoliposomes.

Detailed analyses of sugar-binding kinetics led to selection of two bimane-labeled mutants, one on each surface of the LacY molecule, that exhibit rates of sugar binding very similar to that of WT LacY. Therefore, rates of opening and closing of the periplasmic and cytoplasmic cavities, respectively, were measured in real time with mutants that dynamically resemble the native transporter. One major conclusion from the studies is that there is a direct correlation between the rate of opening of the periplasmic cavity and the rate of sugar binding to LacY inserted into the membrane.

Furthermore, rates of sugar binding and Trp-induced bimane quenching on both the periplasmic and cytoplasmic sides of LacY allow insight into the individual steps involved in the alternating access mechanism. LacY is inserted into proteoliposomes with the same orientation as in the native bacterial membrane, with a sealed periplasmic aspect facing the external milieu (20, 28, 29). Therefore, sugar binding to LacY in proteoliposomes occurs only after spontaneous opening of the outward-facing cavity, and the rate of sugar binding does not exhibit dependence on sugar concentration.

However, once the periplasmic cavity is open, allowing diffusion-limited access of substrate to the binding site, the rate of binding becomes directly dependent upon galactoside concentration. The koff and affinity (Kd) measurements obtained from NPG displacement experiments (Fig. 2 and Fig. S5) allow estimation of the sugar kon (kon = koff/Kd) when the sugar-binding site is readily accessible, and they are determined to be 4.1, 4.4, and 10 μM−1⋅s−1 for reconstituted N137C/Q340W, I32C/N245W, and WT LacY, respectively. The observed binding rates (kobs = koff + kon [NPG]) calculated for 200 μM NPG, for example, are from 900 to 2,100 s−1, which is much faster than the rates of opening of the periplasmic cavity (6–30 s−1), as measured by bimane unquenching on the periplasmic side of LacY. The rate of closing of the periplasmic cavity is similar to the opening rate, as measured by dilution experiments either in DDM (Fig. 4C, trace 5) or in proteoliposomes (Fig. 4D, trace 4). Notably, the rate of conformational change on the periplasmic side is independent of the nature of galactoside, as shown with NPG, TDG, or lactose (Fig. 6 B and C). Moreover, rates of opening of the periplasmic cavity are remarkably similar to turnover numbers for WT LacY in right-side-out membrane vesicles or in reconstituted proteoliposomes with respect to uphill lactose/H+ symport [i.e., active lactose transport (16–21 s−1)], downhill lactose/H+ influx (8–16 s−1), or downhill lactose/H+ efflux (6–9 s−1) (30).

Another important conclusion from these studies is that closing of the cytoplasmic cavity in WT LacY is reciprocally related to opening of the periplasmic cavity, as observed with two cytoplasmic mutants reconstituted into proteoliposomes (brown lines in Fig. 7 A and C and Fig. S8 D and F). Very similar rates are observed for bimane quenching on the cytoplasmic side (4–5 s−1) and for NPG binding (Trp151→NPG FRET) from outside, the latter of which is limited by the rate of opening of the periplasmic cavity (6 s−1) in both cytoplasmic mutants.

Trp-induced bimane quenching/unquenching, coupled with direct measurements of galactoside binding, provides a powerful tool to study the alternating access mechanism of transport. Rates of global conformational change triggered by sugar binding are dissected into events that occur on the cytoplasmic and periplasmic aspects of LacY in a phospholipid membrane. Clearly, the conformational rearrangements in LacY are initiated by spontaneous opening of the periplasmic cavity, which occurs slowly, thereby limiting the rate of sugar binding; it is possible that this step is also the limiting step in the overall transport process.

Methods

Construction of mutants, purification of LacY, reconstitution into proteoliposomes, and materials used in this study are described in SI Methods.

PDT-Bimane Labeling.

Labeling of mutants with PDT-bimane was carried out at 100 μM protein and 100 μM PDT-bimane in 50 mM sodium phosphate (NaPi)/0.02% DDM (pH 7.5) for 10 min at room temperature, followed by washing twice with the same buffer without bimane using an Amicon Ultra concentrator with 50-kDa cutoff (Millipore). TDG (30 mM) was added to the medium for labeling of Cys introduced on the periplasmic side to protect native Cys148 from labeling, and also to increase the probability of opening the periplasmic cavity. Cys replacements on the cytoplasmic side are readily accessible without bound sugar; therefore, Cys148 was replaced with Met, and labeling was carried out without TDG.

TCEP reduction of PDT-bimane–labeled mutants was carried out at 10 μM labeled protein in the presence of 10 mM TCEP (control samples did not contain TCEP) in 50 mM NaPi/0.02% DDM (pH 7.5) for 20 min at room temperature. Samples were diluted 25-fold in 50 mM Na acetate/0.02% DDM (pH 4.7) for bimane fluorescence measurements.

Fluorescence Measurements.

Steady-state fluorescence spectra were measured at room temperature on a SPEX Fluorolog 3 spectrofluorometer (Horiba Scientific) as described (19) with excitation at 295 nm (for Trp and bimane) and 380 nm (for bimane). Stopped-flow measurements were performed at 25 °C on an SFM-300 rapid kinetic system equipped with a TC-50/10 cuvette (dead time = 1.2 ms) and a MOS-450 spectrofluorometer (both from Bio-Logic USA). Excitation was at 295 or 380 nm, with emission interference filters (Edmund Optics) at 340 nm (for Trp) or 447 nm (for bimane). The final concentration of protein after mixing was 0.5–2 μM. The concentration of TDG in displacement experiments was 15 mM. Measurements with purified protein solubilized in DDM were done in 50 mM NaPi/0.02% DDM (pH 7.5). Experiments with proteoliposomes were carried out in 50 mM NaPi (pH 7.5). To dissolve proteoliposomes, DDM was added to a final concentration of 0.3%, and after 10 min, the samples were used in stopped-flow experiments. Typically, 10–30 traces were recorded for each data point, averaged, and fitted with an exponential equation using the built-in Bio-Kine32 software package (Bio-Logic USA) or Sigmaplot 10 (Systat Software, Inc.). All given concentrations were final after mixing unless stated otherwise. For dilution experiments, PDT-bimane–labeled protein, dissolved in DDM or reconstituted into proteoliposomes, was preincubated with NPG at a concentration fivefold higher than the Kd (measured under identical conditions) and mixed by stopped flow with a 10-fold greater volume of buffer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Junichi Sugihara for his skillful help in preparation of mutants. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK51131, DK069463, and GM073210 and National Science Foundation Grant MCB-1129551 (to H.R.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1408374111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Smirnova I, Kasho V, Kaback HR. Lactose permease and the alternating access mechanism. Biochemistry. 2011;50(45):9684–9693. doi: 10.1021/bi2014294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaback HR, Smirnova I, Kasho V, Nie Y, Zhou Y. The alternating access transport mechanism in LacY. J Membr Biol. 2011;239(1-2):85–93. doi: 10.1007/s00232-010-9327-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saier MH., Jr Families of transmembrane sugar transport proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35(4):699–710. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan L, Kaback HR. Lessons from lactose permease. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:67–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madej MG, Kaback HR. The life and times of lac permease: Crystals ain’t enough, but they certainly do help. In: Ziegler C, Kraemer R, editors. Membrane Transporter Function: To Structure and Beyond. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 121–158. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abramson J, et al. Structure and mechanism of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Science. 2003;301(5633):610–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1088196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirza O, Guan L, Verner G, Iwata S, Kaback HR. Structural evidence for induced fit and a mechanism for sugar/H+ symport in LacY. EMBO J. 2006;25(6):1177–1183. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan L, Mirza O, Verner G, Iwata S, Kaback HR. Structural determination of wild-type lactose permease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(39):15294–15298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707688104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaptal V, et al. Crystal structure of lactose permease in complex with an affinity inactivator yields unique insight into sugar recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(23):9361–9366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105687108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nie Y, Kaback HR. Sugar binding induces the same global conformational change in purified LacY as in the native bacterial membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(21):9903–9908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004515107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smirnova I, Kasho V, Sugihara J, Kaback HR. Trp replacements for tightly interacting Gly-Gly pairs in LacY stabilize an outward-facing conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(22):8876–8881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306849110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar H, et al. Structure of sugar-bound LacY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(5):1784–1788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324141111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smirnova I, et al. Sugar binding induces an outward facing conformation of LacY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(42):16504–16509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708258104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madej MG, Soro SN, Kaback HR. Apo-intermediate in the transport cycle of lactose permease (LacY) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(44):E2970–E2978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211183109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaback HR, et al. Site-directed alkylation and the alternating access model for LacY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(2):491–494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609968104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nie Y, Ermolova N, Kaback HR. Site-directed alkylation of LacY: Effect of the proton electrochemical gradient. J Mol Biol. 2007;374(2):356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Majumdar DS, et al. Single-molecule FRET reveals sugar-induced conformational dynamics in LacY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(31):12640–12645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700969104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Y, Guan L, Freites JA, Kaback HR. Opening and closing of the periplasmic gate in lactose permease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(10):3774–3778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800825105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smirnova I, Kasho V, Sugihara J, Kaback HR. Probing of the rates of alternating access in LacY with Trp fluorescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(51):21561–21566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911434106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smirnova I, Kasho V, Sugihara J, Kaback HR. Opening the periplasmic cavity in lactose permease is the limiting step for sugar binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(37):15147–15151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112157108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansoor SE, Farrens DL. High-throughput protein structural analysis using site-directed fluorescence labeling and the bimane derivative (2-pyridyl)dithiobimane. Biochemistry. 2004;43(29):9426–9438. doi: 10.1021/bi036259m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansoor SE, Dewitt MA, Farrens DL. Distance mapping in proteins using fluorescence spectroscopy: The tryptophan-induced quenching (TrIQ) method. Biochemistry. 2010;49(45):9722–9731. doi: 10.1021/bi100907m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janz JM, Farrens DL. Rhodopsin activation exposes a key hydrophobic binding site for the transducin alpha-subunit C terminus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(28):29767–29773. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsukamoto H, Farrens DL, Koyanagi M, Terakita A. The magnitude of the light-induced conformational change in different rhodopsins correlates with their ability to activate G proteins. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(31):20676–20683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Islas LD, Zagotta WN. Short-range molecular rearrangements in ion channels detected by tryptophan quenching of bimane fluorescence. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128(3):337–346. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao X, et al. Coupling ligand structure to specific conformational switches in the beta2-adrenoceptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(8):417–422. doi: 10.1038/nchembio801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smirnova IN, Kasho VN, Kaback HR. Direct sugar binding to LacY measured by resonance energy transfer. Biochemistry. 2006;45(51):15279–15287. doi: 10.1021/bi061632m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herzlinger D, Viitanen P, Carrasco N, Kaback HR. Monoclonal antibodies against the lac carrier protein from Escherichia coli. 2. Binding studies with membrane vesicles and proteoliposomes reconstituted with purified lac carrier protein. Biochemistry. 1984;23(16):3688–3693. doi: 10.1021/bi00311a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun J, Wu J, Carrasco N, Kaback HR. Identification of the epitope for monoclonal antibody 4B1 which uncouples lactose and proton translocation in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1996;35(3):990–998. doi: 10.1021/bi952166w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viitanen P, Garcia ML, Kaback HR. Purified reconstituted lac carrier protein from Escherichia coli is fully functional. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81(6):1629–1633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.