Significance

Chirality plays a vital role in chemical, biological, pharmaceutical, and material sciences. The preparation of enantiomerically pure compounds is a very important and challenging area. In this paper, we developed a highly enantioselective (≥99% ee) and widely applicable method for the synthesis of various γ- and more-remotely chiral alcohols, many of which cannot be satisfactorily prepared by other existing methods, via the ZACA/oxidation–lipase-catalyzed acetylation–Cu- or Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling from terminal alkenes. We also demonstrated MαNP ester analysis is a convenient and powerful method for determining the enantiomeric purities of δ- and ε-chiral primary alkanols. This finding is anticipated to shed light on the relatively undeveloped field of determination of enantiomeric purity and/or absolute configuration of remotely chiral primary alcohols.

Abstract

Despite recent advances of asymmetric synthesis, the preparation of enantiomerically pure (≥99% ee) compounds remains a challenge in modern organic chemistry. We report here a strategy for a highly enantioselective (≥99% ee) and catalytic synthesis of various γ- and more-remotely chiral alcohols from terminal alkenes via Zr-catalyzed asymmetric carboalumination of alkenes (ZACA reaction)–Cu- or Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling. ZACA–in situ oxidation of tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS)-protected ω-alkene-1-ols produced both (R)- and (S)-α,ω-dioxyfunctional intermediates (3) in 80–88% ee, which were readily purified to the ≥99% ee level by lipase-catalyzed acetylation through exploitation of their high selectivity factors. These α,ω-dioxyfunctional intermediates serve as versatile synthons for the construction of various chiral compounds. Their subsequent Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling with various alkyl (primary, secondary, tertiary, cyclic) Grignard reagents and Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling with aryl and alkenyl halides proceeded smoothly with essentially complete retention of stereochemical configuration to produce a wide variety of γ-, δ-, and ε-chiral 1-alkanols of ≥99% ee. The MαNP ester analysis has been applied to the determination of the enantiomeric purities of δ- and ε-chiral primary alkanols, which sheds light on the relatively undeveloped area of determination of enantiomeric purity and/or absolute configuration of remotely chiral primary alcohols.

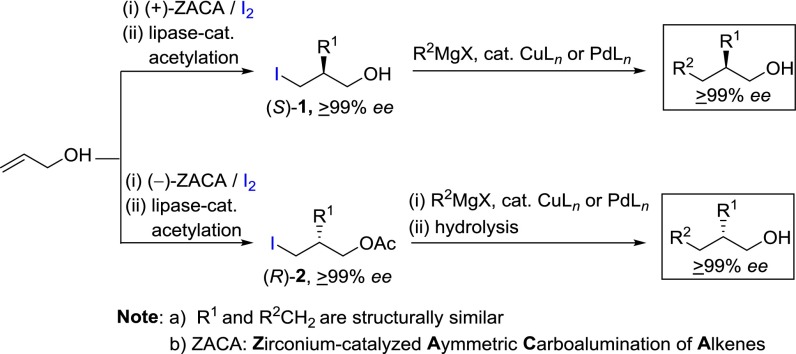

Asymmetric synthesis remains as a significant challenge to synthetic organic chemists as the demand for enantiomerically pure compounds continues to increase. Chirality plays a vital role in chemical, biological, pharmaceutical, and material sciences. The US Food and Drug Administration requires that all chiral bioactive molecules have to be as pure as possible, containing a single pure enantiomer, because chirality significantly influences drugs’ biological and pharmacological properties. As a consequence, development of new methods for asymmetric synthesis of enantiomerically pure compounds (≥99% ee) continues to be increasingly important (1–5). We recently reported a highly selective and efficient method (6) for the preparation of 2-chirally substituted 1-alkanols via a sequence consisting of (i) Zr-catalyzed asymmetric carboalumination of alkenes (ZACA reaction hereafter) (7–10)–in situ iodinolysis of allyl alcohol, (ii) enantiomeric purification by lipase-catalyzed acetylation (11, 12) of both (S)- and (R)-ICH2CH(R)CH2OH (1), the latter obtained as acetate, i.e., (R)-2, and (iii) Cu- or Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling (13, 14) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Strategy for the synthesis of enantiomerically pure 2-alkyl-1-alkanols.

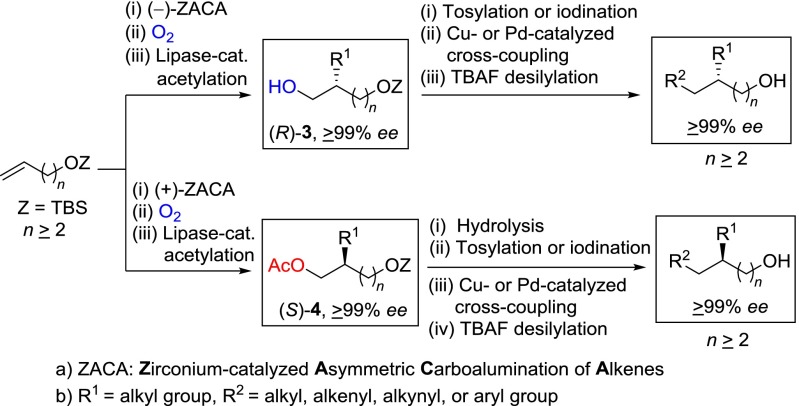

As satisfactory as the procedure shown in Scheme 1 is, however, its synthetic scope is limited to the preparation of 2-chirally substituted 1-alkanols. In search for an alternative and more generally applicable procedure, we came up with a strategy shown in Scheme 2, which, in principle, should be applicable to the synthesis of γ- and more-remotely chiral alcohols of high enantiomeric purity. In contrast to Scheme 1, the alkylalane intermediates prepared by the ZACA reaction of tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS)-protected ω-alkene-1-ols are to be subjected to in situ oxidation with O2 to introduce OH group of α,ω-dioxyfunctional chiral intermediates (3) (Scheme 2). The strategies shown in Schemes 1 and 2 illustrate the versatility of ZACA represented by the organoaluminum functionality of the initially formed ZACA products. Introduction of the OH group by oxidation of initially formed alkylalane intermediates in Scheme 2 is based on two considerations: (i) the proximity of the OH group to a stereogenic carbon center is highly desirable for lipase-catalyzed acetylation to provide ultrapure (≥99% ee) difunctional intermediates, and (ii) the versatile OH group can be further transformed to a wide range of carbon groups by tosylation or iodination followed by Cu- or Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling. The TBS-protected OH group (OTBS) serves not only as a source of OH group in the final desired alkanols, but also as a proximal heterofunctional group leading to higher enantioselectivity in lipase-catalyzed acetylation (11, 12). As long as the α,ω-dioxyfunctional chiral intermediates (R)-3 and (S)-4 can be readily prepared as enantiomerically pure (≥99% ee) substances, their subsequent Cu- or Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling would proceed with retention of all carbon skeletal features to produce a wide range of γ- and more-remotely chiral alcohols in high enantiomeric purity (≥99% ee).

Scheme 2.

Strategy for the synthesis of γ- and more-remotely chiral 1-alkanols.

Results and Discussion

Some key features of the ZACA reaction include (i) catalytic asymmetric C–C bond formation, (ii) use of alkene substances of one-point-binding without requiring any other functional groups, and (iii) many potential transformations of the initially formed alkylalane intermediates (6–10). The ZACA reaction shows a broad substrate scope and a high synthetic potential. With these in mind, we applied this catalytic asymmetric protocol toward the preparation of α,ω-dioxyfunctional key intermediates 3 by ZACA reaction of a few representative TBS-protected ω-alkene-1-ols (Table 1). Thus, commercially available 3-buten-1-ol, 4-penten-1-ol, and 5-hexen-1-ol were protected with TBSCl and imidazole and subjected to the ZACA reaction using Et3Al or nPr3Al (two equivalents), isobutylaluminoxane (IBAO, one equivalent) (15, 16), and a catalytic amount of (–)- or (+)-bis-(neomenthylindenyl)zirconium dichloride [(–)- or (+)-(NMI)2ZrCl2] (17, 18), and then oxidized in situ with O2. The crude alcohols 3 were obtained in 67–78% yields, and their enantiomeric purities ranged from 80% to 88% ee (Table 1).

Table 1.

ZACA reaction of TBS-protected ω-alkene-1-ols

|

IBAO (isobutylaluminoxane): prepared by mixing equimolar quantities of iBu3Al and H2O.

Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral GC or 1H NMR analysis of Mosher esters.

The amount of (–)-(NMI)2ZrCl2 used was 3 mol%.

Enantiomeric purification of α,ω-dioxyfunctional intermediates 3 of 80–88% ee obtained by the ZACA reaction was carried out by lipase-catalyzed acetylation (11, 12), and the results are summarized in Table 2. Amano lipase PS from Pseudomonas cepacia (Aldrich) was generally superior to Amano lipase AK from Pseudomonas fluorescens (Aldrich) in the purification of (R)-3a and 3b (Table 2, entries 1–2 and 5–6). Also, 1,2-dichloroethane proved to be a superior solvent than THF for the purification of (R)-3a and 3b (Table 2, entries 2–3 and 6–7). Thus, (R)-3a, 3b, and 3c were readily purified to the level of ≥99% ee by Amano lipase PS-catalyzed acetylation with vinyl acetate in 1,2-dichloroethane in 60–73% recovery yields. Similarly, Amano lipase PS-catalyzed acetylation of (S)-3b of 85% ee provided acetate (S)-4b, which was hydrolyzed with KOH to form (S)-3b of 97.6% ee in 82% recovery. (S)-3b of 97.6% ee was further subjected to a second round of lipase-catalyzed acetylation/hydrolysis to give (S)-3b of ≥99% ee in 85% recovery (Table 2, entry 10).

Table 2.

Enantiomeric purification of (3) by lipase-catalyzed acetylation

|

Enantiomeric purification of 3 to the ≥99% ee level was highlighted in bold.

Lipase-catalyzed acetylation is S-selective. The acetylation rate of (S)-3 is faster than that of (R)-3.

Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral GC or 1H NMR analysis of Mosher esters.

THF was used instead of 1,2-dichloroethane.

Lipase-catalyzed acetylation was followed by hydrolysis of (S)-4b to give (S)-3b.

To further demonstrate the high efficiency of ZACA–lipase-catalyzed acetylation tandem process for preparation of both (R)- and (S)-α,ω-dioxyfunctional alcohols, one control experiment of lipase-catalyzed acetylation of racemic 3b, prepared in 45% yield by rac-(EBI)ZrCl2-catalyzed carboalumination, was performed. Under the optimal conditions, (R)-3b of ≥99% ee was formed in only 30% recovery by Amano lipase PS-catalyzed acetylation of rac-3b. Furthermore, (S)-3b was obtained in a disappointingly low recovery of 10% with only 87.8% ee (Table 2, entry 11). Thus, it is practically impossible to provide highly pure (S)-3b by lipase-catalyzed acetylation of rac-3b. These results clearly indicate that the ZACA–lipase-catalyzed acetylation tandem protocol provides a more efficient, satisfactory, and general route to both (R)- and (S)-α,ω-dioxyfunctional alcohols in high enantiomeric purity, which should serve as versatile difunctional chiral synthons.

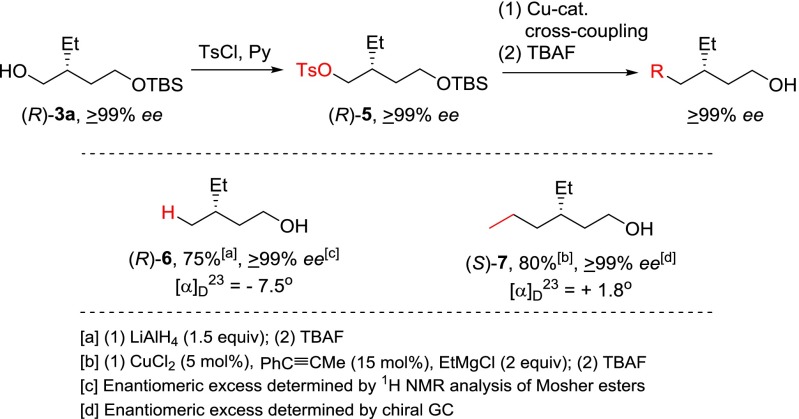

Having established the feasibility of efficiently synthesizing α,ω-dioxyfunctional chiral alcohols 3 in a highly enantioselective and efficient manner, we then turned our attention to the synthesis of γ- and more-remotely and barely chiral (19–21) alcohols of high enantiomeric purity, which have not previously been readily accessible, via key intermediates 3 by Cu- or Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. (R)-3a of ≥99% ee was converted to tosylate (R)-5. (R)-6 and (S)-7 of ≥99% ee were then synthesized by further transformation of (R)-5 via reduction with LiAlH4 (1.5 equivalents) or CuCl2-catalyzed cross-coupling with ethylmagnesium chloride (2 equivalents) and 15 mol% of 1-phenylpropyne (14), followed by removal of the TBS group with tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF), in 75% and 80% yields over three steps, respectively (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of chiral 3-alkyl-1-alcohols from (R)-3a.

For the synthesis of chiral 4-alkyl-1-alkanols of ≥99% ee, (R)-3b was first transformed to the corresponding tosylate (R)-8a or iodide (R)-8b. The preparation of (R)-9 was performed by the reduction of tosylate (R)-8a with LiAlH4 followed by TBAF desilylation in 80% yield over three steps. Tosylate (R)-8a was also subjected to the Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions with different alkylmagnesium chloride reagents to provide (R)-10, (S)-11, and (R)-12 in 77–84% yields. Pd-catalyzed Negishi coupling of aryl and alkenyl halides was used to introduce aryl and alkenyl groups. The preparation of (R)-13 and (R)-14 of ≥99% ee was carried out by zincation of iodide (R)-8b, Pd-catalyzed Negishi coupling (22, 23) with 4-iodotoluene or (E)-ethyl 3-bromoacrylate, and TBAF desilylation in 60% and 58% yields over three steps, respectively (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of chiral 4-alkyl-1-alcohols from (R)-3b.

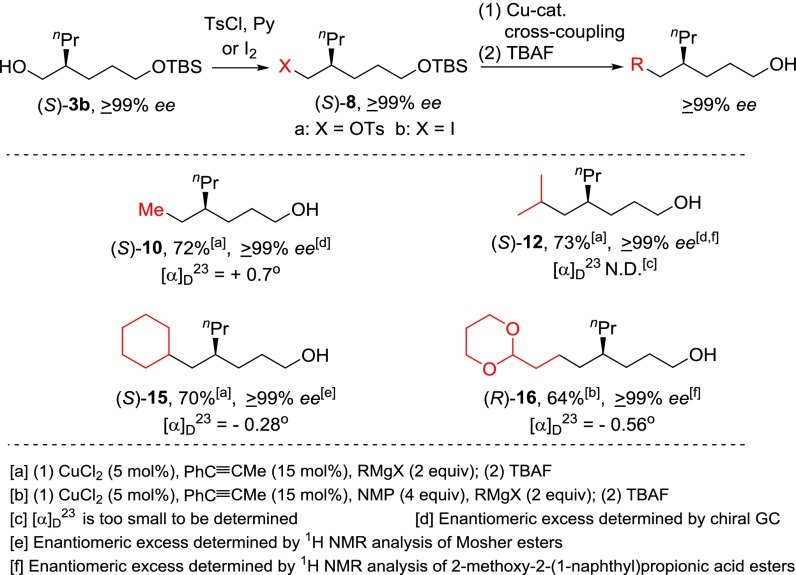

(S)-3b was also used as a key intermediate in the synthesis of chiral 4-alkyl-1-alcohols (S)-10, (S)-12, and (S)-15 via tosylation, CuCl2/1-phenylpropyne-catalyzed cross-coupling with alkylmagnesium chloride reagents (14), and TBAF desilylation in 70–73% yields over three steps, respectively. For the preparation of (R)-16, our initial attempts on the cross-coupling reaction of tosylate (S)-8a with [2-(1,3-dioxan-2-yl)ethyl]magnesium bromide under similar conditions proved unsuccessful. The reaction was not completed, and the product yield was low. When the substrate was changed from tosylate (S)-8a to iodide (S)-8b, and an additive N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP, four equivalents) was added, the CuCl2/1-phenylpropyne-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of iodide (S)-8b with [2-(1,3-dioxan-2-yl)ethyl]magnesium bromide proceeded smoothly. Thus, (R)-16 was synthesized as an enantiomerically pure (≥99% ee) compound in 64% yield over three steps from iodide (S)-8b (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of chiral 4-alkyl-1-alcohols from (S)-3b.

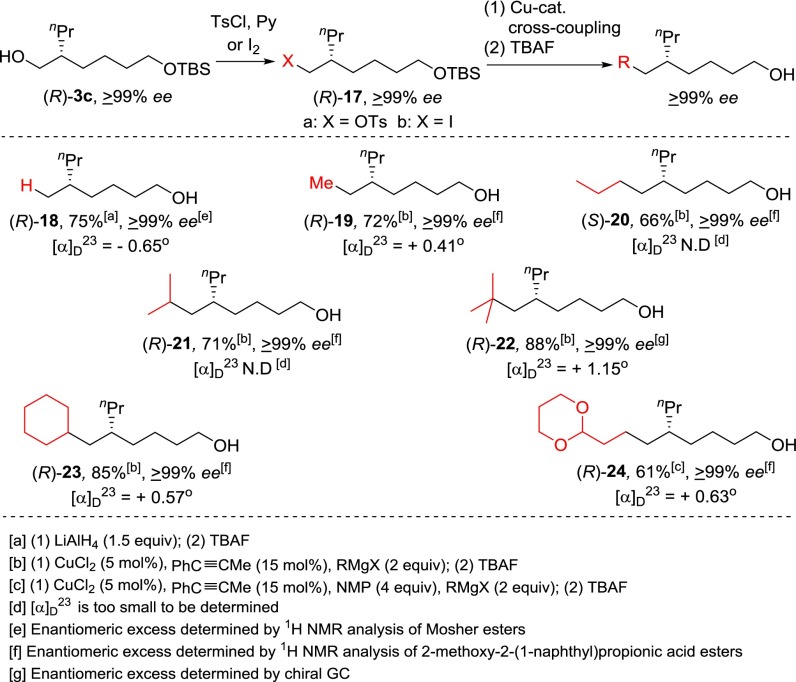

A similar synthetic strategy was used in the synthesis of chiral 5-alkyl-1-alknols of ≥99% ee from the intermediate (R)-3c. Reduction of tosylate (R)-17a with LiAlH4 followed by TBAF desilylation provided (R)-18 in 75% yield. Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of tosylate (R)-17a or iodide (R)-17b with various alkyl (primary, secondary, tertiary, cyclic) Grignard reagents proceeded smoothly to form a wide range of enantiomerically pure (≥99% ee) chiral 5-alkyl-1-alknols 19–24 after deprotection of TBS group (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of chiral 5-alkyl-1-alcohols from (R)-3c.

Having developed a widely applicable route to various γ- and more-remotely chiral alcohols using the ZACA/oxidation–lipase-catalyzed acetylation–Cu- or Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling protocol, our attention was necessarily and increasingly drawn into the methods of determination of the enantiomeric purities of final desired alcohols, which proved to be quite challenging. For most of the alkanols where the stereogenic center generated was in the γ or δ position relative to the OH group, such as compounds 7, 9, 10, 12, and 13, the enantiomeric purities of ≥99% ee were successfully determined by chiral gas chromatography. However, initial attempts to determine the enantiomeric excess in more demanding cases, such as 5-alkyl-1-alcohols 19, 20, 21, 23, and 24 and 4-alkyl-1-alcohols 11 and 16, using chiral GC and HPLC were unsatisfactory.

NMR spectroscopy has become a popular and convenient tool for the determination of enantiomeric purity and absolute configuration of chiral compounds, which is based on transformation of the chiral substrate with a suitable chiral derivatizing agent (CDA) to two different diastereoisomers or conformers that can be differentiated by NMR spectroscopy. Many CDAs including α-methoxy-α-(trifluoromethyl) phenylacetic acid (MTPA or Mosher acid) (24) have been developed for determining the absolute configurations and/or enantiomeric excess of secondary alcohols (24–27). However, few papers reported examples of primary alcohols, which mainly focused on the cases of β-chiral primary alcohols (28–32). Challenges in dealing with primary alcohols stem from the facts that the distance between groups R1/R2 of primary alcohols and the aryl ring of CDA is greater than that in secondary alcohols, leading to lower shielding effects and also reducing the conformational preference by increasing the degree of rotational freedom (Fig. 1). In our previous work, we also used MTPA (24) to determine enantiomeric purities of β-chiral primary alcohols (6). However, in cases where the two alkyl branches of β-chiral primary alcohols at the stereogenic center are closely similar to each other, such as C4H9(C3H7)CHCH2OH, the chemical shifts of the diastereomeric MTPA esters were not sufficiently separated to allow quantitative determination of the enantiomeric purity by 1H NMR or 19F NMR analysis.

Fig. 1.

MTPA and MαNP esters of secondary alcohols as NMR-distinguishable chiral derivatives.

A solution to the difficulty mentioned above was found through the use of 2-methoxy-2-(1-naphthyl)propionic acid (MαNP), which had been used in determining the absolute configuration of chiral secondary alcohols (33, 34). The naphthyl ring of MαNP esters exerts greater anisotropic shielding effects on substituents than phenyl group. As a result, MαNP acid shows greater discrimination than MTPA (24). Indeed, the two terminal methyl groups of the diastereomeric MαNP ester (R,R)- and (R,S)-26, derived from ε-chiral alcohol (R)-19, showed completely separate 1H NMR signals, whereas the diastereomeric MTPA ester 25 had no separation (Fig. 2). The MαNP ester analysis was also successfully applied to chiral discrimination of other δ- and ε-chiral primary alcohols 11, 14, 16, 20, 21, 23, and 24, which demonstrated surprising long-range anisotropic differential shielding effects. It should be noted that the diastereotopic chemical shift differences of MαNP esters were affected by NMR solvent and resonance frequency (MHz) of NMR. d-Acetonitrile, d-acetone, d-methanol and/or CDCl3 have been shown to be suitable solvents. The higher the resonance frequency, the better discrimination of chemical shifts obtained.

Fig. 2.

Methyl resonances in the 1H NMR spectra (CDCl3, 600 MHz) of MTPA ester and MαNP ester derived from (R)-19.

Conclusions

In summary, we developed a widely applicable method for highly enantioselective (≥99% ee) synthesis of various γ- and more-remotely chiral alcohols by the ZACA/oxidation–lipase-catalyzed acetylation–Cu- or Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling strategy herein reported. Once the α,ω-dioxyfunctional chiral intermediates 3 were prepared as enantiomerically pure (≥99% ee) compounds by ZACA/in situ oxidation–lipase-catalyzed acetylation, their subsequent Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling with various alkyl (primary, secondary, tertiary, cyclic) Grignard reagents and Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling with alkenyl and aryl halides proceeded smoothly with essentially full retention of all carbon skeletal features to provide various γ-, δ-, and ε-chiral 1-alkanols of ≥99% ee, many of which cannot be satisfactorily prepared by other existing methods. In view of the easy availability of a wide variety of α-olefins and cross-coupling reagents, we anticipate that ZACA combined with Cu- or Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling would provide a general and efficient route to a broad range of chiral compounds in high enantiomeric purity. We have also demonstrated that the MαNP ester analysis is a convenient and widely applicable method for determining the enantiomeric purities of δ- and ε-chiral primary alkanols, which sheds light on the relatively undeveloped area of determination of enantiomeric purity and/or absolute configuration of remotely chiral primary alcohols.

Materials and Methods

All reactions were run under a dry argon atmosphere. THF and ether was dried by distillation under argon from sodium/benzophenone. CH2Cl2 was dried by distillation under argon from CaH2. Full experimental details and compound characterization data are included in the SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM 36792) and Purdue University for support of this research. We also thank Sigma-Aldrich, Albemarle, Boulder Scientific, and Teijin for support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1401187111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ojima I, et al. In: Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis. Ojima I, editor. Wiley, New York; 2010. pp. 1–998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noyori R. Asymmetric catalysis: Science and opportunities (Nobel lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41(12):2008–2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helmchen G, Pfaltz A. Phosphinooxazolines—a new class of versatile, modular P,N-ligands for asymmetric catalysis. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33(6):336–345. doi: 10.1021/ar9900865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharpless KB. Searching for new reactivity (Nobel lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41(12):2024–2032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trost BM, Crawley ML. Asymmetric transition-metal-catalyzed allylic alkylations: Applications in total synthesis. Chem Rev. 2003;103(8):2921–2944. doi: 10.1021/cr020027w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu S, Lee C-T, Wang G, Negishi E. Widely applicable synthesis of enantiomerically pure tertiary alkyl-containing 1-alkanols by zirconium-catalyzed asymmetric carboalumination of alkenes and palladium- or copper-catalyzed cross-coupling. Chem Asian J. 2013;8(8):1829–1835. doi: 10.1002/asia.201300311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondakov D, Negishi E. Zirconium-catalyzed enantioselective methylalumination of monosubstituted alkenes. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117(43):10771–10772. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kondakov D, Negishi E. Zirconium-catalyzed enantioselective alkylalumination of monosubstituted alkenes proceeding via noncyclic mechanism. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118(6):1577–1578. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Negishi E. Discovery of ZACA reaction: Zr-catalyzed asymmetric carboalumination of alkenes. Arkivoc. 2011;2011(viii):34–53. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu S, Negishi E. Synthesis of chiral heterocyclic compounds via zirconium-catalyzed asymmetric carboalumination of alkenes (ZACA reaction) Heterocycles. 2014;88(2):845–877. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CS, Fujimoto Y, Girdaukas G, Sih CJ. Quantitative analyses of biochemical kinetic resolutions of enantiomers. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104(25):7294–7299. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koeller KM, Wong CH. Enzymes for chemical synthesis. Nature. 2001;409(6817):232–240. doi: 10.1038/35051706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Negishi E. Magical power of transition metals: Past, present, and future (Nobel Lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(30):6738–6764. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terao J, Todo H, Begum SA, Kuniyasu H, Kambe N. Copper-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of grignard reagents with primary-alkyl halides: Remarkable effect of 1-phenylpropyne. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(12):2086–2089. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huo S, Shi JC, Negishi E. A new protocol for the enantioselective synthesis of methyl-substituted alkanols and their derivatives through a hydroalumination/ zirconium-catalyzed alkylalumination tandem process. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41(12):2141–2143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang B, Negishi E. Highly efficient asymmetric synthesis of fluvirucinine A1 via Zr-catalyzed asymmetric carboalumination of alkenes (ZACA)-lipase-catalyzed acetylation tandem process. Org Lett. 2008;10(2):193–195. doi: 10.1021/ol702272d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erker G, et al. The role of torsional isomers of planarly chiral nonbridged bis(indenyl)metal type complexes in stereoselective propene polymerization. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115(11):4590–4601. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Negishi E, Huo S. (2003) (–)-Dichlorobis[(1,2,3,3a,7a-η)-1-[(1S,2S,5R)-5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)]cyclohexyl-1H-inden-1-yl]zirconium and its (+)-(1R,2R,5S)-isomer. e-EROS Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis, 10.1002/047084289X.rn00180.

- 19.Mislow K, Bickart P. An epistemological note on chirality. Isr J Chem. 1976/77;15(1-2):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mislow K. In: Fuzzy Logic in Chemistry. Rouvray DH, editor. Academic Press, New York; 1997. pp. 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mislow K. Absolute asymmetric synthesis: A commentary. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 2003;68(5):849–864. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu GC. The development of versatile methods for palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions of aryl electrophiles through the use of P(t-Bu)3 and PCy3 as ligands. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41(11):1555–1564. doi: 10.1021/ar800148f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Organ MG, et al. A user-friendly, all-purpose Pd-NHC (NHC=N-heterocyclic carbene) precatalyst for the negishi reaction: A step towards a universal cross-coupling catalyst. Chemistry. 2006;12(18):4749–4755. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dale JA, Mosher HS. Nuclear magnetic resonance enantiomer regents. Configurational correlations via nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts of diastereomeric mandelate, O-methylmandelate, and alpha-methoxy-alpha-trifluoromethylphenylacetate (MTPA) esters. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:512–519. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker D. NMR determination of enantiomeric purity. Chem Rev. 1991;91(7):1441–1457. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seco JM, Quiñoá E, Riguera R. The assignment of absolute configuration by NMR. Chem Rev. 2004;104:17–117. doi: 10.1021/cr2003344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seco JM, Quiñoá E, Riguera R. Assignment of the absolute configuration of polyfunctional compounds by NMR using chiral derivatizing agents. Chem Rev. 2012;112(8):4603–4641. doi: 10.1021/cr2003344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finamore E, Minale L, Riccio R, Rinaldo G, Zollo F. Novel marine polyhydroxylated steroids from the starfish Myxoderma platyacanthum. J Org Chem. 1991;56(3):1146–1153. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexakis A, Mutti S, Mangeney P. A new reagent for the determination of the optical purity of primary, secondary, and tertiary chiral alcohols and of thiols. J Org Chem. 1992;57(4):1224–1237. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferreiro MJ, Latypov ShK, Quiñoá E, Riguera R. Determination of the absolute configuration and enantiomeric purity of chiral primary alcohols by 1H NMR of 9-anthrylmethoxyacetates. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 1996;7(8):2195–2198. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciminiello P, Dell’Aversano C, Fattorrusso E, Forino M, Magno S. Assignment of the absolute stereochemistry of oxazinin-1: Application of the 9-AMA shift-correlation method for β-chiral primary alcohols. Tetrahedron. 2001;57(38):8189–8192. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukui H, Fukushi Y, Tahara S. NMR determination of the absolute configuration of β-chiral primary alcohols. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46(30):5089–5093. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harada N, et al. 2-Methoxy-2-(1-naphthyl)propionic acid, a powerful chiral auxiliary for enantioresolution of alcohols and determination of their absolute configurations by the 1H NMR anisotropy method. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2000;11(6):1249–1253. doi: 10.1002/chir.10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasai Y, et al. Conformational analysis of MαNP esters, powerful chiral resolution and 1H NMR anisotropy tools—Aromatic geometry and solvent effects on Δδ values. Eur J Org Chem. 2007;2007(11):1811–1826. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.