Significance

In recent years there has been extensive research toward the development of sustainable polymeric materials. However, environmentally benign, bioderived polymers still represent a woefully small fraction of plastics and elastomers on the market today. To displace the widely useful oil-based polymers that currently dominate the industry, a bioderived synthetic polymer must be both cost and performance competitive. In this paper we address this challenge by combining the efficient bioproduction of β-methyl-δ-valerolactone with controlled polymerization techniques to produce economically viable block polymer materials with mechanical properties akin to commercially available thermoplastics and elastomers.

Keywords: rubbery polyester, block copolymer, biobased production, mevalonate pathway

Abstract

Development of sustainable and biodegradable materials is essential for future growth of the chemical industry. For a renewable product to be commercially competitive, it must be economically viable on an industrial scale and possess properties akin or superior to existing petroleum-derived analogs. Few biobased polymers have met this formidable challenge. To address this challenge, we describe an efficient biobased route to the branched lactone, β-methyl-δ-valerolactone (βMδVL), which can be transformed into a rubbery (i.e., low glass transition temperature) polymer. We further demonstrate that block copolymerization of βMδVL and lactide leads to a new class of high-performance polyesters with tunable mechanical properties. Key features of this work include the creation of a total biosynthetic route to produce βMδVL, an efficient semisynthetic approach that employs high-yielding chemical reactions to transform mevalonate to βMδVL, and the use of controlled polymerization techniques to produce well-defined PLA–PβMδVL–PLA triblock polymers, where PLA stands for poly(lactide). This comprehensive strategy offers an economically viable approach to sustainable plastics and elastomers for a broad range of applications.

Polymeric materials account for nearly $400 billion in economic activity annually and represent the third largest manufacturing industry in the United States (1). Currently petroleum-derived polymers—for example polyethylene, polystyrene, and polyvinylchloride—dominate this market. Although these materials are widely useful, their manufacture and disposal present inescapable environmental challenges that are costly to correct and simply unsustainable in the long term. To ensure the continued vitality of the polymer enterprise, it is necessary to invent high-performance polymers that are both sustainable and cost-competitive. In recent years, ingenious advances in synthetic biology have enabled the economical production of fuels (2–7), chemicals (8–12), and complex natural products (13–16) from renewable sugars. This elegant manipulation of existing organisms to efficiently produce valuable metabolites from inexpensive feedstocks represents a triumph of modern science and engineering and offers society the promise of renewable, environmentally compatible next-generation materials.

Whereas there has been steady scientific progress toward the production of synthetic polymers from renewable resources, the fraction of high-performing, biobased, degradable polymers on the market is today minuscule (1). Arguably the most successful example to date is poly(lactide) (PLA), a compostable aliphatic polyester derived from the fermentation product lactic acid. However, the brittle nature of PLA and other commercial aliphatic polyesters such as poly(butylene succinate) and poly(hydroxyalkanoate)s has thwarted their broad-based utility. Expanded market penetration will pivot on the development of products endowed with tunable combinations of properties, e.g., soft, ductile, and tough (17, 18). Among myriad strategies that have been used to this end, PLA-containing block polymers represent a particularly attractive approach. These hybrid materials offer opportunities to easily tune a wide range of physical and mechanical properties by controlling molecular architecture, composition, and molar mass.

A specific example that illustrates the utility of this approach is ABA triblock thermoplastic elastomers. Here, rigid (glassy or semicrystalline) “A” endblocks microphase separate to form nanoscopic domains that tether together the soft, low glass transition temperature (Tg) regions comprised of the center block “B” component (19–22). This design results in outstanding mechanical properties and has been the basis for the commercially successful poly(styrene)–poly(diene) variants (23). Many PLA-containing block polymers have been reported; several have been shown to be flexible, tough, elastic, and hydrolytically degradable (24–27). Unfortunately the starting materials used to prepare these polymers are either derived from fossil fuels or from natural products that are prohibitively expensive. The development of an economically viable rubbery polymer that can be used in combination with PLA to prepare mechanically superior block polymers therefore is the grand challenge that must be addressed for these materials to be competitive with the analogous styrenic block polymers.

The need for an efficient, scalable, process to a methyl branched lactone suitable for ring-opening transesterification polymerization (ROTEP) led us to examine candidates that could be produced by biosynthesis with both high titer and high yield. After surveying the appropriate metabolic pathways, we identified β-methyl-δ-valerolactone (βMδVL) as an attractive target. Based on our experience with simple aliphatic polyesters we anticipated that the elastomeric polymer PβΜδVL could be combined with hard semicrystalline or glassy poly(lactide) (PLLA or PLA, respectively) to produce P(L)LA–PβMδVL–P(L)LA triblock polymers that offer exceptional mechanical properties (26, 27). βMδVL can be generated by direct fermentation of glucose or through the production of the intermediate compound mevalonate. These two approaches to βMδVL, one entirely biochemical and the other semisynthetic, represent facile chemical transformations (Fig. 1). Because the theoretical yield of this lactone monomer is 0.42 g/g glucose, we estimate that this product can be produced for less than $2 a kilogram (Table S1), compatible with large-volume commodity applications.

Fig. 1.

(A) Total biosynthetic pathway for the production of βMδVL. (B) A semisynthetic route to produce βMδVL from mevalonate. (C) Conversion of βMδVL to an elastomeric triblock polymer that can be repeatedly stretched to 18 times its original length without breaking.

With the bioderived βMδVL in hand, we demonstrated that bulk ROTEP using an organocatalyst proceeds at room temperature to high conversion, yielding an amorphous polyester with Tg = –51 °C (26, 28). Simple chain extension through reaction with lactide (LLA or LA) leads to P(L)LA–PβMδVL–P(L)LA triblock polymers that can be tuned to have mechanical properties ranging from stiff tough plastics to soft and highly extendible elastomers (Fig. 1C).

Results

Construction of a Nonnatural Metabolic Pathway for Biosynthesis of βMδVL.

Because βMδVL is not a natural metabolite, we constructed an artificial biosynthetic pathway to create an engineered Escherichia coli strain (Fig. 1A). Our biosynthetic strategy builds on the mevalonate pathway that previously has been engineered for the synthesis of artemisinin and terpenoids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and E. coli, respectively (29, 30). In this work we improved the production of mevalonate in E. coli and also expanded the pathway to synthesize βMδVL from this precursor. The overall nonnatural pathway has three components: (i) overexpression of the mevalonate-producing enzymes; (ii) introduction of the fungal siderophore proteins to synthesize anhydromevalonolactone (AML); (iii) reduction of AML to βMδVL by enoate reductases.

To generate an acetoaceyl-CoA pool we used the E. coli endogenous enzyme acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase AtoB. First HMG-CoA synthase (MvaS) and HMG-CoA reductase (MvaE) were cloned to provide a route for the production of mevalonate from this pool. To maximize mevalonate flux, the Protein-Protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BlastP) was used to identify MvaS and MvaE from various organisms: Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Lactobacillus casei, Methanococcus maripaludis, and Methanococcus voltae. Combinatorial tests were used to identify the optimum set of MvaS and MvaE for mevalonate production (Fig. 2A and Table S2). high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses indicated that, with the exception of MvaS from M. maripaludis and M. voltae, all heterologous enzymes were active in E. coli. The strain expressing both mvaS and mvaE genes from L. casei produced 14.6 g L–1 mevalonate from 40 g L–1 glucose, better than any other combination (V in Fig. 2A). The strain expressing the L. casei enzymes produced 50% more mevalonate than other engineered E. coli strains described in previous work (30–32).

Fig. 2.

Total biobased production of βMδVL and semisynthetic route to this monomer. (A) Fermentation of mevalonate from different combinations of MvaS and MvaE. MvaE from E. faecalis plus MvaS from: I, E. faecalis; II, Staphylococcus aureus; III, L. casei. MvaS from L. casei plus MvaE from: IV, S. aureus; V, L. casei; VI, M. maripaludis; VII, M. voltae. (B) Anhydromevalonolactone fermentation with siderophore enzymes SidI and SidH from: A, A. fumigatus; B, N. crassa; C, P. nodorum; D, S. sclerotiorum. (C) Production of βMδVL through fermentation with enoate-reductase: 1, Oye2 from S. cerevisiae; 2, Oye3 from S. cerevisiae; 3, wild-type YqjM from B. subtilis; 4, Mutant YqjM (C26D and I69T) from B. subtilis. (D) Production of mevalonate by fermentation of glucose in a 1.3-L bioreactor. (E) Acid catalyzed dehydration of mevalonate to anhydromevalonolactone monitored by refractive index (RI). (F) NMR spectrum of purified βMδVL prepared via hydrogenation of anhydromevalonolactone. Data shown in A–C include error bars that identify the range of the results obtained from three experiments (n = 3).

To biosynthesize anhydromevalonolactone from mevalonate, we explored the potential of siderophore pathway enzymes. In fungi acyl-CoA ligase SidI converts mevalonate to mevalonyl-CoA, and enoyl-CoA hydratase SidH transforms mevalonyl-CoA to anhydromevalonyl-CoA (33). We speculated that anhydromevalonyl-CoA could spontaneously cyclize into anhydromevalonolactone intracellularly. To test this hypothesis, we synthesized sidH and sidI genes based on E.-coli-optimized codons for protein expression. Using BlastP analysis, homologous SidI and SidH from Aspergillus fumigatus, Neurospora crassa, Phaeosphaeria nodorum, and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum were chosen for fermentation experiments (34). Results revealed that the strain expressing SidI and SidH from A. fumigatus produced 730 mg L–1 anhydromevalonolactone; the strain carrying enzymes from N. crassa also generated 540 mg L–1 anhydromevalonolactone (Fig. 2B and Table S3). The other two enzyme pairs did not function properly in E. coli.

To explore the reduction of anhydromevalonolactone to βMδVL by enoate reductases, we cloned Oye2 and Oye3 from S. cerevisiae (35), wild-type and mutant YqjM (C26D and I69T) from Bacillus subtilis (36). The strains carrying the anhydromevalonolactone pathway and Oye2 or mutant YqjM successfully produced 180 or 270 mg L–1 βMδVL, respectively, directly from glucose (Fig. 2C and Table S4). Thus, we successfully constructed an artificial biosynthetic pathway to βMδVL from glucose.

Semisynthesis of βMδVL from Mevalonate.

Whereas directed evolution approaches undoubtedly will improve the aforementioned βMδVL biosynthetic pathway (5), we also developed a semisynthetic approach for the immediate large-scale production of βMδVL. In this route the fermented mevalonate is first dehydrated to anhydromevalonolactone, then reduced to βMδVL (Fig. 1B).

To scale up the production of mevalonate, the E. coli strain carrying genes from L. casei was tested for fermentation in a 1.3-L bioreactor. During the fermentation, the strain achieved a productivity of 2 g L–1h–1 mevalonate with the final titer reaching 88 g L–1 (Fig. 2D and Table S5). The yield for this semibatch fermentation was 0.26 g/g glucose. To prepare anhydromevalonolactone we added sulfuric acid directly to the fermentation broth and heated to reflux to catalyze the dehydration of mevalonate (Fig. 2E and Fig. S1). At a catalyst loading of 10% by volume, 98% of the mevalonate was converted to anhydromevalonolactone with a selectivity of 89% (Table S6). The resulting anhydromevalonolactone was isolated by solvent extraction using chloroform and hydrogenated to βMδVL using Pd/C as the catalyst (bulk, room temperature, 350 psi H2, 12 h) to >99% conversion. The crude product was subsequently purified by distillation to obtain polymerization-grade monomer (Fig. 2F).

Polymerization of βMδVL.

Based on previous work with alkyl-substituted δ-valerolactones, we suspected the ceiling temperature for the polymerization of βMδVL might be low (28, 37, 38). To favor high conversion we therefore conducted the polymerizations in bulk monomer at room temperature using the highly active organocatalyst triazabicyclodecene (TBD) (Fig. 3) (39). The addition of TBD to neat βMδVL in the presence of benzyl alcohol (BnOH) as the initiator ([βMδVL]0/[TBD]0/[BnOH]0 = 492/1/1.7) resulted in the rapid production of poly(βMδVL)—within 1 h at room temperature (T = 18 °C) 75% of the monomer was consumed, within 3 h the reaction approached equilibrium (Fig. S2). Determination of the residual monomer concentration over a range of temperatures allowed us to calculate the thermodynamic parameters for this polymerization ( and ); these values correspond to a ceiling temperature (Tc) of 227 °C for the polymerization of neat βMδVL. Practically, the limiting conversion for the bulk polymerization is about 91% and 60% at 18 °C and 120 °C, respectively (Fig. S3). At 18 °C with as little as 0.05 wt% TBD, the bulk polymerization is well controlled with the conversion and ratio of monomer to added initiator dictating the molar mass of the polymer (Table S7). Using the diol initiator 1,4-phenylenedimethanol we obtained dihydroxy terminated poly(βMδVL).

Fig. 3.

Polymerization of βMδVL leading to PβMδVL and chain extension with (±)- or (-)-lactide (LA or LLA) yielding P(L)LA–PβMδVL–P(L)LA triblock polymer. TBD and HO-R-OH represent triazabicyclodecene and 1,4-phenylenedimethanol, respectively.

Synthesis and Mechanical Properties of Block Copolymers.

Poly(βMδVL) is an amorphous aliphatic polyester with a low glass transition temperature (Tg = –51 °C). To explore the potential of this rubbery polymer as the soft segment in thermoplastic elastomers we used dihydroxy terminated poly(βMδVL) to prepare triblock polymers with PLA endblocks. This was easily accomplished by adding a solution of (±) or (–)-lactide (LA or LLA) directly to a polymerization of βMδVL that was near equilibrium (Fig. 3). [Alternatively, purfied telechelic poly(βMδVL) (free of residual monomer and catalyst) could be dissolved in a solution of lactide, and the polymerization initiated by addition of TBD.] Although depolymerization can be problematic for poly(βMδVL) when diluted in the presence of TBD, the conversion of βMδVL was virtually unchanged before and after the chain extension with lactide, suggesting that the addition of lactide to the end of the poly(βMδVL) prevents significant depolymerization. Compared with the poly(βMδVL) macroinitiators, polymers prepared using either extension strategy exhibited expected increases in mass average molar mass (Mm) as determined by multiangle laser light scattering-size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 4A). In addition, the 13C NMR spectra of the resulting triblocks revealed no evidence of significant tranesterification between the poly(βMδVL) and poly(lactide) blocks, consistent with clean formation of the desired ABA triblock architecture (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

(A) Overlay of size exclusion chromatography traces obtained from PβMδVL (20.0 kg mol−1) and a corresponding PLLA–PβMδVL–PLLA (9.1–20.0–9.1 kg mol−1) triblock polymer. (B) 13C NMR spectra obtained from (Bottom) PβMδVL, (Middle) PLLA (10.0 kg mol−1), and (Top) PLLA–PβMδVL–PLLA (9.1–20.0–9.1 kg mol−1). (C) DSC thermograms recorded for (Bottom) PβMδVL and (Middle) PLA–PβMδVL–PLA (16.2–20.0–16.2 kg mol−1), and (Top) PLLA–PβMδVL–PLLA (9.1–20.0–9.1 kg mol−1). Data were taken while heating at a rate of 5 °C min−1 after cooling from 200 °C at the same rate. (D) SAXS pattern recorded at room temperature from PLA–PβMδVL–PLA (16.2–20.0–16.2 kg mol−1). Diffraction peaks at q*=0.185 nm−1, 2q*, 3q*, and 4q* are consistent with a periodic (d = 33 nm) lamellar morphology.

Despite the structural similarity of poly(lactide) and poly(βMδVL), P(L)LA–P(βMδVL)–P(L)LA triblock polymers readily microphase separate at only moderate molar masses as evidenced by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Both PLA–P(βMδVL)–PLA [from (±)-lactide, LA] and PLLA–P(βMδVL)–PLLA [from (-)-lactide, LLA] exhibit separate glass transitions for the midblock and endblock segments by DSC (Fig. 4C). In addition, the SAXS data from these triblocks showed well-defined scattering peaks that correspond to self-assembled nanostructures with principal spacings ranging from 20 to 50 nm (Fig. 4D and Table S8).

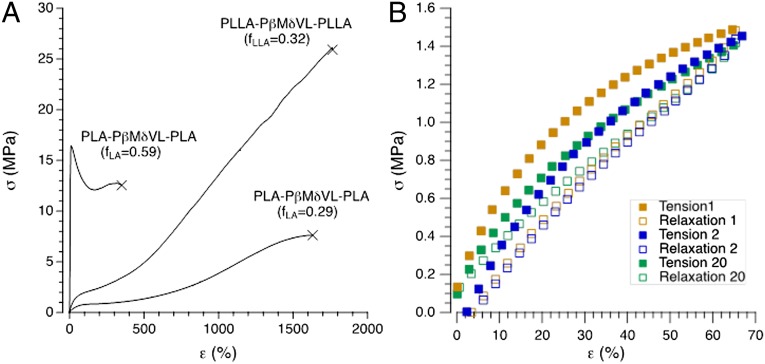

Predictably, the mechanical and thermal properties of these ordered block polymers are influenced by molar mass, tacticity of the poly(lactide) segments, and composition. By changing the endblock from the minority component (fLA = 0.29) to the majority component (fLA = 0.59) it is possible to access either elastomers or tough plastics. Moreover, at a fixed composition and molar mass, the use of semicrystalline PLLA endblocks leads to remarkably strong elastomers that rival commercially available petroleum based block copolymers in terms of recoverability, tensile strength, and ultimate elongation (Fig. 5 and Table S9) (23).

Fig. 5.

(A) Representative stress (σ) versus strain (ε) results obtained in uniaxial extension for triblock polymers containing different volume fractions of semicrystalline (fLLA) and glassy (fLA) blocks. Incorporation of relatively small amounts of the hard block (fLA = 0.29 and fLLA = 0.32) results in a soft (elastic modulus E = 1.9 and 5.9 MPa, respectively), highly extendable elastic material. Increasing the hard block content (fLA = 0.59) leads to a stiff (E = 229 MPA) and ductile plastic. (B) Stress versus strain response of PLLA–PβMδVL–PLLA (18.6–70.0–18.6 kg mol−1) (fLLA = 0.32) during cyclic loading (1–20 cycles) to 67% strain at a rate of 5 mm min−1. These results demonstrate nearly ideal elastic behavior with nearly complete recovery of the applied strain.

Conclusion

We have developed a semisynthetic approach to βMδVL from glucose that relies upon the fermentation of mevalonate and subsequent transformation of mevalonate to βMδVL. The high titer of the fermentation (88 g L−1) and the efficiency of the chemical reactions used to produce the final product make the overall process scalable and commercially promising. We also have described a nonnatural total biosynthetic pathway for the production of βMδVL , which obviates the need for additional chemical transformations. Optimization of this all-biosynthetic process (i.e., titer and yield comparable to the semisynthetic route) would further reduce the production cost of βMδVL. This bioderived monomer can be readily converted from the neat state to a rubbery hydroxytelechelic polymer using controlled polymerization techniques at ambient temperature; addition of either (±) or (-)-lactide to a poly(βMδVL) midblocks leads to well-defined ABA triblock polymers. We have shown that the thermal and mechanical properties of these materials can be tuned by controlling molar mass, architecture, and endblock tacticity and have specifically demonstrated thermoplastic elastomers with properties similar to commercially available styrenic block polymers. This work lays the foundation for the production of new biobased polymeric materials with a wide range of potential properties and applications.

Materials and Methods

For details, see SI Appendix.

Plasmids and Strains.

All cloning procedures were carried out in the E. coli strain XL10-gold (Stratagene). Genes for mevalonate and βMδVL pathway were either PCR amplified from genomic DNA templates or codon-optimized and synthesized by GenScript. Three kinds of plasmids have been constructed for the biosynthesis of βMδVL (Fig. S4). BW25113 (rrnBT14 ΔlacZWJ16 hsdR514 ΔaraBADAH33 ΔrhaBADLD78) transformed with the relevant plasmids was used to produce mevalonate or βMδVL.

Culture Condition and Analysis.

E. coli strains were growth at 37 °C in 2XYT rich medium (16 g/L Bacto-tryptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, and 5 g/L NaCl) supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin 100 μg/mL and kanamycin 50 μg/mL). Shake flask fermentations were performed with 125-mL conical flasks containing M9 medium. After adding 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside, the fermentation was performed for 48 h at 30 °C. Scale-up fermentation was performed in 1.3 L Bioflo 115 Fermentor (NBS). The culturing condition was set at 34 °C, dissolved oxygen level 20%, and pH 7.0. The concentrations of metabolites were measured by HPLC.

Dehydration, Hydrogenation, and Purification.

The fermentation supernatant was treated with concentrated H2SO4 to dehydrate mevalonate into anhydromevalonolactone. The reaction temperature was 121 °C. Chloroform was used to extract anhydromevalonolactone from the reaction mixture. The results of dehydration are shown in Fig. S1 and Table S6. For hydrogenation, unreduced palladium on activated carbon [10% (wt/wt) Acros Organics] was used as the catalyst. In a typical hydrogenation procedure, 10 g of catalyst were added to a 300 mL high-pressure reactor with 50 mL anhydromevalonolactone. The reaction was then allowed to stir under H2 (∼350 pounds per square inch gauge) at room temperature overnight to ensure quantitative conversion. The crude βMδVL was dried over calcium hydride for 12 h and then distilled under vacuum (50 mTorr, 30 °C); the distilled product was passed through dry basic alumina using cyclohexane as an eluent. The cyclohexane was removed under vacuum to obtain purified βMδVL.

Polymer Synthesis.

To synthesize poly(βMδVL) a monofunctional (benzyl alcohol) or difunctional (1,4 benzene dimethanol) alcohol was added to monomer in a pressure vessel or glass vial and stirred with a magnetic stir bar until completely dissolved. The ratio of monomer to alcohol was varied to target polymers of different molecular weights. When the initiator was dissolved, an appropriate amount of catalyst (∼0.05–0.2 mol% TBD or ∼0.5 mol% diphenyl phosphate) relative to monomer was added to initiate the polymerization. The reaction was stirred and the conversion monitored using 1H NMR of crude quenched aliquots. Poly((L)LA)-b-poly(βMδVL)-b-poly((L)LA) was prepared from a previously isolated and purified poly(βMδVL). The poly(βMδVL) prepolymer was first dissolved in a 1 M solution of (±)- lactide or (–)-lactide in dichloromethane. After dissolution of the prepolymer, 0.1 mol% TBD (relative to lactide) was added. The solution was stirred for 10 min and then quenched by adding 5 equivalents of benzoic acid relative to TBD. The crude polymer samples were purified by precipitation in methanol from dichloromethane/chloroform and subsequently dried.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

D.K.S. thanks Byeongdu Lee for assistance with acquisition of SAXS data, and Justin Bolton for photography assistance. Funding for this work was provided by the Center for Sustainable Polymers at the University of Minnesota, a National Science Foundation (NSF)-supported Center for Chemical Innovation (CHE-1136607). The BioTechnology Institute at the University of Minnesota is also acknowledged for support. Portions of this work were performed at Sector 12-IDB of the Advanced Photon Source (APS). Use of the APS, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the US DOE under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. Additional parts of this work were carried out in the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering Characterization Facility, which receives partial support from NSF through the National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network program.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1404596111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Miller SA. Sustainable polymers: Opportunities for the next decade. ACS Macro Lett. 2013;2(6):550–554. doi: 10.1021/mz400207g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atsumi S, Hanai T, Liao JC. Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels. Nature. 2008;451(7174):86–89. doi: 10.1038/nature06450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu P, et al. Modular optimization of multi-gene pathways for fatty acids production in E. coli. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1409. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellomonaco C, Clomburg JM, Miller EN, Gonzalez R. Engineered reversal of the β-oxidation cycle for the synthesis of fuels and chemicals. Nature. 2011;476(7360):355–359. doi: 10.1038/nature10333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bastian S, et al. Engineered ketol-acid reductoisomerase and alcohol dehydrogenase enable anaerobic 2-methylpropan-1-ol production at theoretical yield in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2011;13(3):345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steen EJ, et al. Microbial production of fatty-acid-derived fuels and chemicals from plant biomass. Nature. 2010;463(7280):559–562. doi: 10.1038/nature08721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enquist-Newman M, et al. Efficient ethanol production from brown macroalgae sugars by a synthetic yeast platform. Nature. 2014;505(7482):239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature12771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yim H, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for direct production of 1,4-butanediol. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(7):445–452. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tseng HC, Prather KL. Controlled biosynthesis of odd-chain fuels and chemicals via engineered modular metabolic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(44):17925–17930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209002109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Achkar J, Xian M, Zhao H, Frost JW. Biosynthesis of phloroglucinol. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(15):5332–5333. doi: 10.1021/ja042340g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Causey TB, Zhou S, Shanmugam KT, Ingram LO. Engineering the metabolism of Escherichia coli W3110 for the conversion of sugar to redox-neutral and oxidized products: homoacetate production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(3):825–832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337684100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SJ, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of 5-aminovalerate and glutarate as C5 platform chemicals. Metab Eng. 2013;16:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajikumar PK, et al. Isoprenoid pathway optimization for Taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science. 2010;330(6000):70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1191652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma SM, et al. Complete reconstitution of a highly reducing iterative polyketide synthase. Science. 2009;326(5952):589–592. doi: 10.1126/science.1175602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ro DK, et al. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature. 2006;440(7086):940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfeifer BA, Admiraal SJ, Gramajo H, Cane DE, Khosla C. Biosynthesis of complex polyketides in a metabolically engineered strain of E. coli. Science. 2001;291(5509):1790–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.1058092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson KS, Schreck KM, Hillmyer MA. Toughening polylactide. Pol Rev. 2008;48(1):85–108. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsui A, Wright ZC, Frank CW. Biodegradable polyesters from renewable resources. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2013;4:143–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061312-103323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bates FS, et al. Multiblock polymers: Panacea or Pandora’s box? Science. 2012;336(6080):434–440. doi: 10.1126/science.1215368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morton M. Structure-property relations in amorphous and crystallizable ABA triblock copolymers. Rubb Chem Technol. 1983;56(5):1096–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmalz H, Abetz V, Lange R. Thermoplastic elastomers based on semicrystalline block copolymers. Compos Sci Technol. 2003;63(8):1179–1186. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handlin D, Trenor S, Wright K. Applications of Thermoplastic Elastomers Based on Styrenic Block Copolymers. Macromolecular Engineering. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2007. pp. 2001–2032. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kraton Performance Polymers Inc. Product Families Kraton D SBS. Available at www.kraton.com/products/Kraton_D_SBS.php. Accessed March 11, 2014.

- 24.Olsén P, Borke T, Odelius K, Albertsson AC. ε-decalactone: A thermoresilient and toughening comonomer to poly(L-lactide) Biomacromolecules. 2013;14(8):2883–2890. doi: 10.1021/bm400733e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin JO, Chen WL, Shen ZQ, Ling J. Homo- and block copolymerizations of ε-decalactone with L-lactide catalyzed by lanthanum compounds. Macromolecules. 2013;46(19):7769–7776. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martello MT, Hillmyer MA. Polylactide-poly(6-methyl-ε-caprolactone)-polylactide thermoplastic elastomers. Macromolecules. 2011;44(21):8537–8545. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wanamaker CL, O’Leary LE, Lynd NA, Hillmyer MA, Tolman WB. Renewable-resource thermoplastic elastomers based on polylactide and polymenthide. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(11):3634–3640. doi: 10.1021/bm700699g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakayama A, et al. Synthesis and degradability of a novel aliphatic polyester: poly(β-methyl-δ-valerolactone-co-L-lactide) Polymer. 1995;36(6):1295–1301. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paddon CJ, et al. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature. 2013;496(7446):528–532. doi: 10.1038/nature12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin VJ, Pitera DJ, Withers ST, Newman JD, Keasling JD. Engineering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for production of terpenoids. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(7):796–802. doi: 10.1038/nbt833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang J, et al. Enhancing production of bio-isoprene using hybrid MVA pathway and isoprene synthase in E. coli. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e33509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabata K, Hashimoto S. Production of mevalonate by a metabolically-engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Lett. 2004;26(19):1487–1491. doi: 10.1023/B:BILE.0000044449.08268.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yasmin S, et al. Mevalonate governs interdependency of ergosterol and siderophore biosyntheses in the fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(8):E497–E504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106399108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gründlinger M, et al. Fungal siderophore biosynthesis is partially localized in peroxisomes. Mol Microbiol. 2013;88(5):862–875. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall M, et al. Asymmetric bioreduction of activated C=C bonds using Zymomonas mobilis NCR enoate reductase and old yellow enzymes OYE 1–3 from Yeasts. Eur J Org Chem. 2008;2008(9):1511–1516. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bougioukou DJ, Kille S, Taglieber A, Reetz MT. Directed evolution of an enantioselective enoate-reductase: Testing the utility of iterative saturation mutagenesis. Adv Synth Catal. 2009;351(18):3287–3305. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Save M, Schappacher M, Soum A. Controlled ring-opening polymerization of lactones and lactides initiated by lanthanum isopropoxide, 1. General aspects and kinetics. Macromol Chem Phys. 2002;203(5-6):889–899. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martello MT, Burns A, Hillmyer M. Bulk ring-opening transesterification polymerization of the renewable δ-decalactone using an organocatalyst. ACS Macro Lett. 2012;1(1):131–135. doi: 10.1021/mz200006s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiesewetter MK, et al. Cyclic guanidine organic catalysts: What is magic about triazabicyclodecene? J Org Chem. 2009;74(24):9490–9496. doi: 10.1021/jo902369g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.