Abstract

Importance

Although early mortality in severe psychiatric illness is linked to smoking and alcohol, no studies have comprehensively characterized substance use behavior in severe psychotic illness. In particular, recent assessments of substance use in individuals with mental illness are based on population surveys that do not include individuals with severe psychotic illness.

Objective

To compare substance use in individuals with severe psychotic illness to substance use in the general population.

Design

We assessed comorbidity between substance use and severe psychotic disorders in the Genomic Psychiatry Cohort (GPC). The GPC is a clinically assessed, multi-ethnic sample consisting of 9,142 individuals with the diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder with psychotic features, or schizoaffective disorder, and 10,195 population controls.

Primary Outcome Measures

Smoking (smoked > 100 cigarettes lifetime), heavy alcohol use (> 4 drinks/day), heavy marijuana use (>21 times of marijuana use in a single year), and recreational drug use.

Results

Relative to the general population, individuals with severe psychotic disorders have increased risk of smoking (OR 4.6, 95% CI 4.3-4.9), heavy alcohol use (OR 4.0, 95% CI 3.6-4.4), heavy marijuana use (OR 3.5, 95% CI 3.2-3.7), and recreational drug use (OR 4.6, 95% CI 4.3-5.0). All ethnicities (African American, Asian, European American, and Hispanics) and both sexes have greatly elevated risks of smoking, alcohol, marijuana, and drug use. Of specific concern, recent public health efforts that have successfully decreased smoking among individuals under age 30 appear to have been ineffective among individuals with severe psychotic illness (p-value for interaction effect between age and severe mental illness on smoking initiation P=4.5 × 10−5).

Conclusions and Relevance

In the largest assessment of substance use among individuals with severe psychotic illness to date, we found odds of smoking, alcohol, and other substance use to be dramatically higher than recent estimates of substance use in mild mental illness.

Individuals with severe mental illness die approximately 25 years earlier than the general population and the cause of this early death is largely due to medical illness that can be attributed to substance use disorders 1-3. For example, although suicide and injury are more common among individuals with chronic mental illness, 60% of premature deaths in persons with schizophrenia are due to medical conditions including heart and lung disease and infectious illness caused by modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and IV drug use1. In addition to early mortality, the severity and prognosis of the primary mental illness is worsened in the context of substance dependence 4,5.

The 2009-2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) identified adults with mental illness (based on 14-items related to psychological distress and disability) and found that 36% of adults with mental illness are current smokers, relative to 21% of adults without mental illness 6. In addition, they found that adult smokers with mental illness are less likely to quit than adult smokers without mental illness. This discrepancy highlights the public health disparity in the mentally ill, a uniquely vulnerable population.

In addition to increased smoking among individuals with mental illness, alcohol and other substance use disorders have increased prevalence in individuals with mental illness 7-17. Several large epidemiological surveys have assessed comorbidity of affective and psychotic illness with tobacco, alcohol and drug use disorders in the general population 8,9,12,16,18-20. In these studies, alcohol and drug dependence were found to be more than twice as common among individuals with anxiety disorders, affective disorders, and psychotic disorders9,10,13,16,21. There is also evidence that associations between substance use/dependence and other psychiatric illness are true for both men and women 18, and extend to African Americans 22 and Hispanics 7.

Despite strong epidemiological studies of the general population showing increased comorbidity of smoking, alcohol, and drug use in mental illness, these studies do not address comorbidity of smoking, alcohol and drug use in severe psychotic illness. Not only is severe psychotic illness rare in the general population, but individuals with severe psychotic illness are difficult to contact in general population surveys, and so there is no large-scale survey of substance use among clinically ascertained individuals with severe psychotic illness. Specifically, it is unknown whether the rates of substance use among individuals with mild mental illness, as ascertained in population surveys, apply to individuals with severe psychosis. To address this issue, we assessed substance use in a large, multi-ethnic sample of individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder with psychotic features, and corresponding population controls. Using this powerful sample, we are able to not only gain insight into substance use among individuals with severe psychosis, but also determine the differences in substance use between genders, and racial/ethnic subgroups.

Methods

The Genomic Psychiatry Cohort (GPC) program is a multi-institutional collaboration 23. This resource includes a NIMH managed repository of genomic samples and detailed clinical and demographic data for investigations of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The current sample consists of 9,142 individuals with either the diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder with psychotic features, and 10,195 population controls. Individuals with bipolar disorder without psychotic features represented a relatively small subgroup (n=621) and are therefore not included in these analyses.

Psychiatric diagnoses

Individuals were collected through 12 clinical collaborating sites across the United States. All individuals ascertained to the GPC completed a screening questionnaire eliciting demographic (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender) data as well as a brief personal and family psychiatric and medical history. Individuals with psychotic illness were ascertained as in-patients in acute care or chronic care facilities, and out-patient settings. Control subjects were drawn from the same geographic area as cases, either within health care facilities or as community volunteers recruited from internet advertising or community groups (e.g. church congregations, health fair attendees) and screened to ensure absence of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder within themselves and their first degree relatives.

To confirm the psychiatric diagnoses, case subjects were interviewed by trained clinicians using a structured psychiatric interview instrument, the Diagnostic Interview for Psychosis and Affective Disorder (DI-PAD). The DI-PAD is based on the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS24) and includes 90 phenomenological symptom items that are used with the Operational Criteria Checklist (OPCRIT) computer algorithm 25 to arrive at diagnoses using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)26). Clinicians confirmed diagnoses for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder with psychosis based on DSM-IV criteria.

Substance use measurements

As part of the screening questionnaire, a set of questions were asked of all participants regarding the individual's substance use. The questions were adapted from the DIGS 24, and other validated instruments 27,28.

Do you often have more than 4 drinks in one day?

Over your lifetime, have you smoked more than 100 cigarettes?

Have you ever had a period of one month or more when you smoked cigarettes every day?

Have you ever smoked marijuana more than 21 times in a single year?

Have you ever used recreational (street) drugs [other than marijuana] or prescription drugs more than 10 times to feel good or get high?

Epidemiological Sample

To benchmark our sample with epidemiological studies, we looked at items in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), a population-based epidemiological survey on substance use 29. Because the controls used for this dataset were drawn almost exclusively from the Los Angeles area, we restricted the surveyed data to subjects age 20-55 from California. We used the following items, directly corresponding to the substance use measurements in the GPC:

During the past 30 days ... on how many days did you have 5 or more drinks on the same occasion (DR5DAY)? [an answer of > 3 (weekly or more) was used to correspond to GPC item 1]

Have you smoked 100 cigarettes in your entire life (CIG100LF)?

Has there ever been a period in your life when you smoked cigarettes every day for at least 30 days (CIGDLYMO)?

Total # of days used marijuana in the past 12 months (MJYRTOT). [an answer of > 0 was used to correspond to GPC item 4]

Illicit drug use (except marijuana), past year (IEMYR).

Statistical analysis

The goal of this study is to evaluate substance use in individuals with chronic psychotic disorders (cases) as compared to population controls. With the 5 measures listed above as independent variables, we used logistic regression to model the probability of substance use based on case/control status, adjusted for race & ethnicity, gender, age (< age 30, age 30-49, or ≥ age 50), and recruitment site. We also evaluated whether there are significant interactions on substance use between case control status and race & ethnicity, gender, or age. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 for Windows30.

Results

Table 1 compares the demographics of the sample across controls and the four psychiatric diagnoses that constitute our sample of individuals with chronic psychotic disorder: schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder depressed subtype, schizoaffective disorder bipolar subtype, and bipolar disorder with psychotic features. The sample used for this study is a multi-ethnic sample, including African Americans, Asians, European Americans and Hispanics. There are more female subjects with bipolar disorder than with schizophrenia (p<0.001). There is a wide age range among all individuals, although cases are older than the controls in this sample (p<0.001). Therefore, further analyses evaluate associations between the severe psychotic disorders and substance use only after adjusting for race/ethnicity, age, and gender.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Bipolar with psychosis |

Schizoaffective bipolar subtype |

Schizoaffective depressed subtype |

Schizophrenia | Controls | NSDUH Population survey |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1,507 | 1,486 | 552 | 5,586 | 10,311 | 18,612 |

| Hispanic | 18% | 19% | 14% | 15% | 34% | 37.9% |

| African American | 18% | 24% | 30% | 35% | 17% | 6.2% |

| Asian | 2% | 2% | 1% | 2% | 7% | -- |

| European American | 55% | 46% | 49% | 39% | 37% | 40% |

| mixed race | 4% | 4% | 2% | 3% | 2% | -- |

| % female | 51% | 42% | 45% | 30% | 56% | 49% |

| % male | 49% | 58% | 55°% | 70% | 44% | 51% |

| Age | ||||||

| Average | 43 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 38 | 38 |

| 25th percentile | 33 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 25 | 28 |

| 75th percentile | 51 | 52 | 52 | 53 | 49 | 47 |

The prevalence of various measures of substance use are much higher among individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder (both depressed and bipolar subtype), and bipolar disorder with psychotic features (Table 2). For ease of interpretation, we classified individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders, and bipolar disorder with psychotic features as “cases with severe psychotic disorder,” and analyzed substance use with respect to case/control status. The prevalence of these measures is uniformly high in individuals with severe psychotic illness relative to the control populations. The odds ratio of cases versus controls for each measure of substance use is given in Table 3. Overall, the smoking measures were more strongly associated with case/control status than alcohol or other drugs, with estimated odds ratios of 4.61 for smoking >100 cigarettes (p < 1.0 E-325), and 5.11 for daily smoking >1 month (p<1.0 E-325). The estimated odds ratios for alcohol use (OR 3.96, p=1.2 E-188), marijuana use (OR 3.47, p=2.6 E-254), and recreational drug use (OR 4.62, p<1.0 E-325) were also highly clinically and statistically significant.

Table 2.

Prevalence of substance use measures across psychiatric diagnoses.

| Bipolar w/Psychosis | Schizophrenia | Schizoaffective-Bipolar | Schizoaffective-Depressed | Controls | NSDUH Population survey | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1,501 | 5,582 | 1,482 | 555 | 10,194 | 18,290 |

| Alcohol > 4/day | 26% | 28% | 29% | 30% | 8% | 9.5% |

| 100 cigarettes | 74% | 74% | 80% | 75% | 33% | 34% |

| daily smoking > 1 month | 71% | 72% | 79% | 73% | 29% | 29% |

| Marijuana > 21xs in a year | 52% | 43% | 54% | 49% | 18°% | 16% |

| Recreational drugs > 10xs | 53% | 35% | 54% | 45% | 12% | 10% |

Table 3.

Prevalence of substance use measures compared between cases with chronic psychotic illness and controls. ORs are calculated from logistic regression modeling probability of symptom as a function of diagnosis, adjusted for gender, race, age, and data collection site.

| OR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | estimate | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | P | |

| Alcohol > 4 /day | 19,878 | 3.96 | 3.61 | 4.35 | 1.2 ×10−188 |

| 100 cigarettes | 19,931 | 4.61 | 4.31 | 4.94 | < 1.0 × 10−325 |

| daily smoking > 1 month | 19,882 | 5.11 | 4.78 | 5.46 | < 1.0 × 10−325 |

| Marijuana > 21xs in a year | 19,859 | 3.47 | 3.23 | 3.72 | 2.6 ×10−254 |

| Recreational drugs > 10xs | 19,864 | 4.62 | 4.27 | 4.99 | < 1.0 × 10−325 |

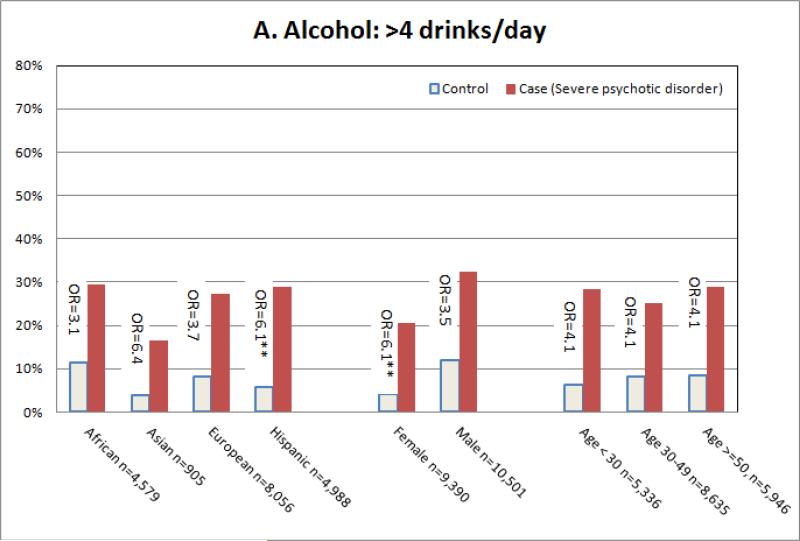

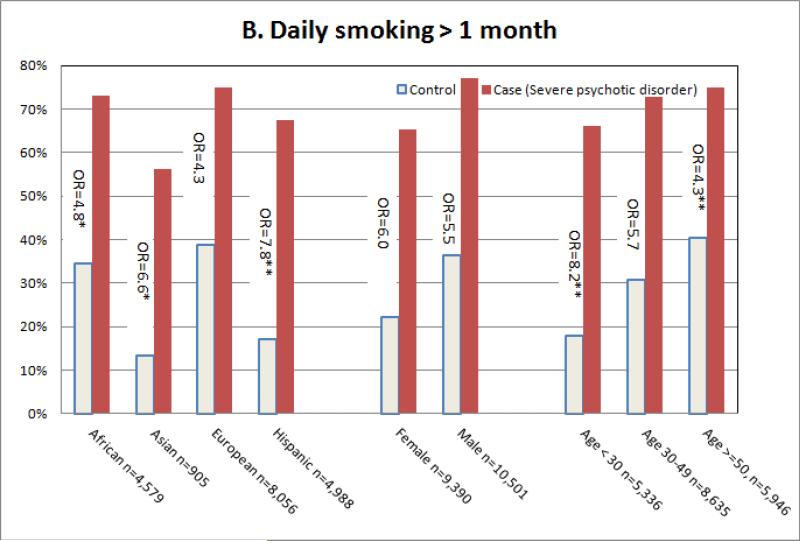

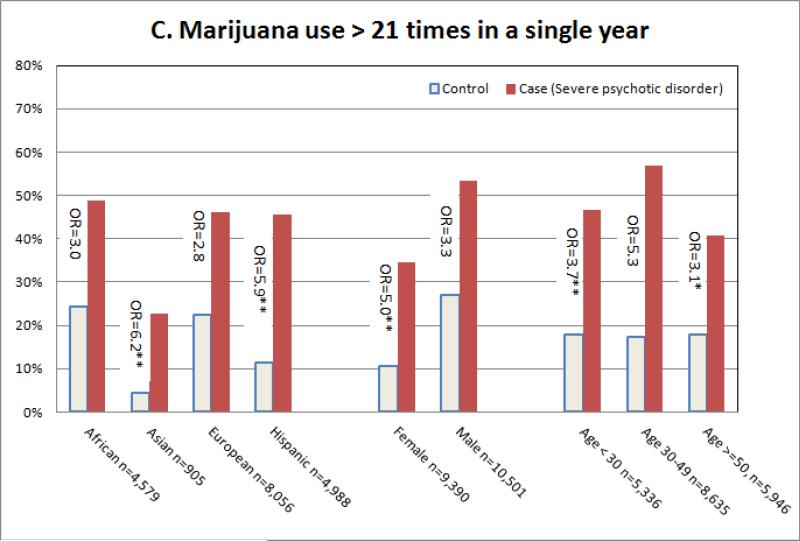

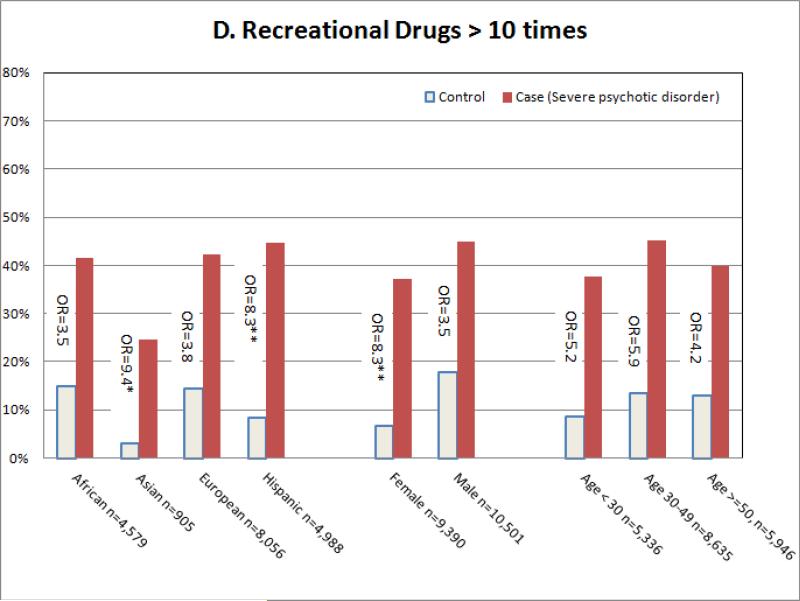

Although the prevalence of measures of substance use across gender, race/ethnic group, and age group varies, it is markedly higher among individuals with psychotic illness within each group. We tested whether the association between substance measures and case/control status is stronger within each group (i.e. whether there is a statistical interaction between case/control status and group). All the items measured showed similar patterns of association. For illustrative purposes, Figure 1 illustrates select associations between substance use and severe psychosis. In groups where the controls had lower rates of substance use (Asians and Hispanics relative to European Americans, females relative to males, and individuals under age 30 relative to 30-50 year olds), the odds ratios were significantly higher than the reference odds ratios, leading to statistically significant interaction effects. This suggests that although belonging to certain groups may be protective for substance use in the control population, this protective effect is lost with the development of a severe mental illness. For example women are at lower risk for using recreational drugs in the general population (7% of women versus 18% of men in the general population have used recreational drugs at least 10 times), but the rates of recreational drug use are much more comparable between men and women among individuals with severe psychosis (37% of women versus 45% of men with severe psychosis have used recreational drugs at least 10 times).

Figure 1.

Frequency of alcohol (Figure 1A), smoking (Figure 1B), marijuana (Figure 1C) and other drug (Figure 1D) use contrasted among subgroups. Odds ratios correspond to odds of the prevalence of the symptom among cases with chronic psychotic illness versus controls. The OR's are contrasted with one another. When an OR is statistically different from the reference (European descent for ethnicity, male for gender, and 30-49 for age group), this is indicated by * (p<0.05) or ** (p<0.001).

Discussion

Individuals with severe mental illness bear an enormous burden due to smoking, alcohol and drug use. In a large, multi-ethnic sample we found substance use among individuals with severe psychotic disorder to be markedly higher than in population controls at a rate that far exceeds previous estimates based on assessments in individuals with mild mental illness 6. This association extends across substances (alcohol, smoking, and other drugs), across psychiatric diagnosis (bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia), across race and ethnicity (African American, Hispanic, Asian, and European American), across genders, and across age groups. This is the first large-scale study to robustly demonstrate these associations across subgroups. Although substance use among individuals with psychotic disorders has been documented 12,13,20,31, this study shows that there is a continuing pressing need to target smoking, alcohol, marijuana, and drug use among individuals with severe mental illness.

The most striking finding of this study is the evidence that societal-level protective effects do not extend to individuals with severe mental illness. Specifically, we found that among groups with lower than average rates of substance use (Hispanics and Asians relative to European Americans, and females relative to males), the protective effects of belonging to these groups did not carry over to individuals with severe psychotic disorder: the odds of substance use increased to mitigate the protective effects. For example, relative to non-Hispanic whites, individuals of Hispanic ethnicity have lower rates of heavy alcohol use in controls (5.7% of n=3,424 in Hispanics, 8.1% of n=3,748 in non-Hispanic European Americans, p<0.0001). However, individuals of Hispanic descent with severe psychotic illness have higher rates of heavy alcohol use than non-Hispanic European Americans (28.8% of n=1,583 in Hispanics, 27.3% of n=4,343 in non-Hispanic whites, p=0.001). This highlights the need for targeting substance use specifically among individuals with severe psychotic illness, as protective influences may not carry over from the general population.

The strongest associations between severe psychotic illness and substance use were seen with cigarette use. This is notable because most of the mortality seen in severe psychiatric illness is due to smoking related disorders. Also, it appears that recent public health efforts that have successfully decreased smoking in the general population have not been effective in individuals with severe psychotic disorder. Specifically, the decrease in smoking among individuals under age 30 that has been seen among the general population 32 and is present in the controls in this dataset does not extend to cases: the OR of smoking daily for a month or more is 8.2 among individuals younger than 30, which is significantly higher than the OR of 5.2 among individuals age 30-49, and the OR of 3.9 among individuals age 50 or older (interaction p=4.5 × 10−5). Given that (1) early mortality in cases is largely due to cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, and (2) many psychotropic medications used to treat psychotic symptoms have severe metabolic side effects that increase the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, it is imperative that we specifically target smoking in these individuals. This is consistent with relatively recent calls for the field of psychiatry to specifically target smoking in severe mental illness15.

Although these data illuminate characteristics of substance use in psychotic disorders in a large, multi-ethnic population, further study is required to better understand the nature of the comorbidity between psychotic disorders and substance dependence. The first step is to specifically evaluate comorbid substance dependence in individuals with severe psychotic illness, rather than individual measures of use as assessed in this study. In addition, the validity and reliability of this series of questions has not been established in any population. However, this series of questions was extracted from the DIGS, a standardized instrument with high test/retest validity and reliability. A further limitation of this study is that it is not a population survey. Because the individuals were not randomly sampled, there may be biases in the dataset that limit extrapolation of the rates of substance use to the general populations of both cases with severe psychotic illness and controls without a personal or family history of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. However, the sample was not selected for substance use, so therefore the odds ratios of substance use for cases versus controls should be accurate.

Nicotine, alcohol and other drugs of abuse target dopaminergic, glutamatergic, and GABAergic transmission, which are also involved in the pathophysiology of severe mental illness. Specifically, nicotine can increase the metabolism of anti-psychotics by activation of the cytochrome P450 enzymes 33, and is thus hypothesized to help reduce side effects of individuals taking antipsychotics. Conversely, exposure to substances increases risk of severe mental illness: marijuana use at age 16 is associated with psychosis at age 19 34, and smoking precedes the onset of symptoms of mental illness 35,36. Additionally, substance use leads to higher rates of psychiatric emergencies and hospitalizations 37. This highlights the importance of understanding the biological connection between substance use and severe mental illness.

In summary, the prevalence of substance use in severe psychosis has been underestimated, and spans social and cultural strata. This is the largest study of substance use in individuals with severe psychotic illness to date. The study not only highlights the comorbid pathology of substance use among those with severe psychotic illness, it also suggests that public health efforts to reduce substance use have not been successful in one of our most vulnerable populations, individuals with severe psychotic illness. It is time to use our recent scientific and public health advancements to improve scientific understanding of the comorbidity between substance use and psychotic disorders, and improved treatment of both.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded by NIH grants U10 AA008401, UL1 RR024992, P01 CA089392, R01 MH085548, R01 MH085542, K08 DA062380-1, KL2 RR024994, and K01 DA025733; and American Cancer Society grant ACS IRG-58-010-54. Laura J. Bierut is listed as an inventor on Issued U.S. Patent 8,080,371,“Markers for Addiction” covering the use of certain SNPs in determining the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of addiction.

Dr. Sarah Hartz had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributor Information

Sarah M. Hartz, Washington University in St. Louis.

Carlos N. Pato, University of Southern California.

Helena Medeiros, University of Southern California.

Patricia Cavazos-Rehg, Washington University in St. Louis.

Janet L. Sobell, University of Southern California.

James A. Knowles, University of Southern California.

Laura J. Bierut, Washington University in St. Louis.

Michele T. Pato, University of Southern California.

References

- 1.Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, Foti ME. Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Medical Directors Council. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006 Apr;3(2):A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and Mortality in Persons With Schizophrenia: A Swedish National Cohort Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Jan 15; doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady KT, Killeen T, Jarrell P. Depression in alcoholic schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1993 Aug;150(8):1255–1256. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drake RE, Wallach MA. Substance abuse among the chronic mentally ill. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989 Oct;40(10):1041–1046. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.10.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged >/=18 years with mental illness - United States, 2009-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Feb 8;62:81–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jimenez-Castro L, Hare E, Medina R, et al. Substance use disorder comorbidity with schizophrenia in families of Mexican and Central American ancestry. Schizophr Res. 2010 Jul;120(1-3):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Biol Psychiatry. 2005 Oct 15;58(8):668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997 Apr;54(4):313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koola MM, McMahon RP, Wehring HJ, et al. Alcohol and cannabis use and mortality in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2012 Aug;46(8):987–993. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. Jama. 2000 Nov 22-29;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 May;64(5):543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore E, Mancuso SG, Slade T, Galletly C, Castle DJ. The impact of alcohol and illicit drugs on people with psychosis: the second Australian national survey of psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012 Sep;46(9):864–878. doi: 10.1177/0004867412443900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prochaska JJ. Integrating tobacco treatment into mental health settings. Jama. 2010 Dec 8;304(22):2534–2535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. Jama. 1990 Nov 21;264(19):2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickerson F, Stallings CR, Origoni AE, et al. Cigarette smoking among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in routine clinical settings, 1999-2011. Psychiatr Serv. 2013 Jan 1;64(1):44–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Anthony JC, Blazer DG, et al. The US National Comorbidity Survey: overview and future directions. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 1997 Jan-Apr;6(1):4–16. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00008575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merikangas KR, Ames M, Cui L, et al. The impact of comorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Oct;64(10):1180–1188. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helzer JE, Pryzbeck TR. The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 1988 May;49(3):219–224. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hickman NJ, 3rd, Delucchi KL, Prochaska JJ. A population-based examination of cigarette smoking and mental illness in Black Americans. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010 Nov;12(11):1125–1132. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pato MT, Sobell JL, Medeiros H, et al. The Genomic Psychiatry Cohort: Partners in Discovery. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32160. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nurnberger JI, Jr., Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994 Nov;51(11):849–859. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. discussion 863-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farmer AE, Wessely S, Castle D, McGuffin P. Methodological issues in using a polydiagnostic approach to define psychotic illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1992 Dec;161:824–830. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.6.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association . Task Force on DSM-IV. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitchens JM. Does this patient have an alcohol problem? Jama. 1994 Dec 14;272(22):1782–1787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, et al. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol. 1994 Mar;55(2):149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. [July 30, 2013];National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2010-2011 [Google Scholar]

- 30.SAS 9.2 [computer program] Cary, NC (c): pp. 2000–2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jun 16;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The NSDUH Report: Trends in Cigarette Use among Adolescents and Young Adults. Rockville, MD: Apr 12, 2012. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desai HD, Seabolt J, Jann MW. Smoking in patients receiving psychotropic medications: a pharmacokinetic perspective. CNS drugs. 2001;15(6):469–494. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffith-Lendering MF, Wigman JT, Prince van Leeuwen A, et al. Cannabis use and vulnerability for psychosis in early adolescence--a TRAILS study. Addiction. 2013 Apr;108(4):733–740. doi: 10.1111/add.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodman E, Capitman J. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among teens. Pediatrics. 2000 Oct;106(4):748–755. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kandel DB, Davies M. Adult sequelae of adolescent depressive symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986 Mar;43(3):255–262. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030073007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark RE, Samnaliev M, McGovern MP. Treatment for co-occurring mental and substance use disorders in five state Medicaid programs. Psychiatric services. 2007 Jul;58(7):942–948. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.7.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]