Abstract

An in vitro antidiabetic activity on α-amylase and α–glucosidase activity of novel 10-chloro-4-(2-chlorophenyl)-12-phenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amines (3a–3f) were evaluated. Structures of the synthesized molecules were studied by FT-IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, EI-MS, and single crystal X-ray structural analysis data. An in silico molecular docking was performed on synthesized molecules (3a–3f). Overall studies indicate that compound 3e is a promising compound leading to the development of selective inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase.

1. Introduction

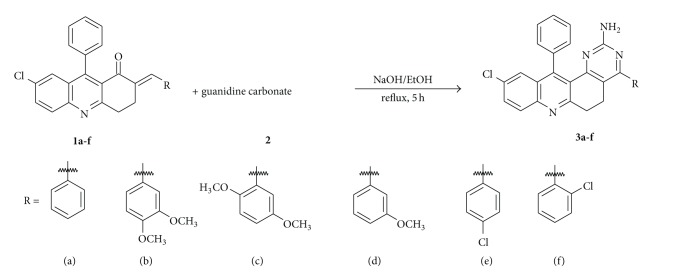

Pyrimidine is a well-known biologically active nitrogen containing heterocyclic compound. In recent years researchers are much interested in the synthesis of pyrimidine analogues. Pyrimidine derivatives posse fungicidal [1], herbicidal [2], antidepressant [3], and antitumor properties [4, 5]. Synthetically prepared amino pyrimidine derivatives display a wide range of biological activities such as antibacterial [6], antitumor [7], and antiviral [8, 9]. Therefore, the substituted amino pyrimidine structure can be found in diverse clinically approved drugs. Interestingly, a substituted amino pyrimidine moiety was also suggested to account for the antioxidant activity [10]. Among those amino pyrimidine heterocycle, 2-aminopyrimidines have been widely used as pharmacophores for drug discovery. 2-Aminopyrimidines constitute a part of the DNA base pair molecules [11]. Compounds having potent anticancer activity, CDK inhibitory activity, I [12–14], antiproliferative activity [15], kinase inhibitor, II [16], antibacterial agents [17], antitumor, III, antidiabetic activity [18], antimalarial, IV, antiplasmodial agents [19], antimicrobial activity, V [20], and anti-inflammatory activity, VI [21] (Figure 1), contain amino pyrimidine moiety in the structure. The tricyclic, planar acridine moiety is responsible for intercalation between base pairs of double-stranded DNA through π-π interactions and, therefore, causes alteration in the cellular machinery [22]. Intercalative interaction of structurally related well-known intercalators, 9-aminoacridine (9AA), and proflavine (PF) was determined by means of fluorescence quenching study [23].

Figure 1.

I CDK inhibitor, II kinase inhibitor, III antitumor, IV antimalarial, V antimicrobial, and VI anti-inflammatory.

Due to numerous biological applications of 2-aminopyrimidine and acridine amine and its analogues, we have focused our research on synthesis of 2-aminopyrimidine by using pharmacologically important structural scaffold acridine pharmacophore.

Protein-ligand interaction is comparable to the lock-and-key principle, in which the lock encodes the protein and the key is grouped with the ligand. The major driving force for binding appears to be hydrophobic interaction [24]. In silico techniques helps identifying drug target via bioinformatics tools. They can also be used to explore the target structures for possible active sites, generate candidate molecules, dock these molecules with the target, rank them according to their binding affinities, and further optimize the molecules to improve binding characteristics [25]. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a leading noncommunicable disease which affects more than 100 million people worldwide and is considered as one of the fine leading diseases which causes death in the world [26]. Type-2 diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder that results from defects in both insulin secretion and insulin action. Management of type-2 diabetes by conventional therapy involves the inhibition of degradation of dietary starch by glucosidases such as α-amylase and α-glucosidase [27]. The pathogenesis of type-2 diabetes involves progressive development in insulin resistance associated with a defect in insulin secretion, leading to overt hyperglycemia. However, compounds which improve insulin sensitivity and glucose intolerance are somewhat limited warranting the discovery and characterization of novel molecules targeting various pathways involved in the pathogenesis of type-2 diabetes [28]. Currently, there are few drugs that are able to counteract the development of the associated pathologies. Therefore, the need to search for new drug candidates in this field appears to be critical. Aromatic amines and thiazolidinones nuclei would produce new compounds with significant antidiabetic properties [29].

In our research group, we have already reported larvicidal activity of 7-chloro-3,4-dihydro-9-phenylacridin-1(2H)-one and (E)-7-chloro-3,4-dihyro-phenyl-2-[(pyridin-2-yl)methylene]acridin-1(2H)-one [30]. In continuation of our research work on acridine moiety, presently we focus on the synthesis of 10-chloro-4-(2-chlorophenyl)-12-phenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine, 3a–3f derivatives. All the synthesized dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amines analogues, 3a–3f, were evaluated for docking and in vitro antidiabetic activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

Melting points were determined by open capillary method and are corrected with standard benzoic acid. All solvents were distilled and dried prior to use. TLC was performed on silica gel G and the spots were exposed to iodine vapour for visualization. A mixture of petroleum ether and ethyl acetate was used as an eluent at different ratio. Column chromatography was performed by using silica gel (60–120 mesh). 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 on a Bruker advance 400 MHz instrument. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm using TMS as the internal standard. IR spectra were obtained on a Perkin-Elmer spectrum RXI FT-IR spectrometer (400–4000 cm−1; resolution: 1 cm−1) using KBr pellets. Molecular mass was determined using ESI-MS THERMO FLEET spectometer.

2.2. Biological Assays

The dialysis membrane, 1,4-α-D glucan-glucanohydrolase, α-amylase, α-glucosidase, P-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside, and acarbose were purchased from Himedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India. All other chemicals and reagents were AR grade purchased locally.

2.3. General Synthesis of 10-Chloro-4,12-diphenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine, 3a–3f

10-Chloro-4,12-diphenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amines, 3a–3f, were synthesized via., (E)-2-benzylidene-7-choloro-3,4-dihydro-9-phenylacridin-1(2H)-ones, 1a–1f, (3,9511 g, 0.01 mol) were mixed with guanidine carbonate 2 (0.9008 g, 0.01 mol) and 10 mL of 10% alc. NaOH (1 g in 10 mL ethanol) and then heated under reflux condition for 5 h. After the completion of the reaction, reaction mixture was cooled and poured into crushed ice. The crude product was separated by column chromatography using 10–15% of ethyl acetate and pet ether solvent to get the target compounds, 3a–3f. The synthetic scheme was presented in Scheme 1 and physical data of all synthesized derivatives were summarized in Table 1.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 10-chloro-4,12-diphenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amines, 3a–3f.

Table 1.

Summary of synthesized 2-aminopyrimidine derivatives (3a–f) via Scheme 1.

| S. no. | Compounds | R | M.P. (°C) | Yield% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3a | -H | 194–196 | 70 |

| 2 | 3b | -3,4-OCH3 | 218–220 | 81 |

| 3 | 3c | -2,5-OCH3 | 212–214 | 75 |

| 4 | 3d | -2-OCH3 | 168–170 | 69 |

| 5 | 3e | -4-Cl | 210–212 | 71 |

| 6 | 3f | -2-Cl | 238–240 | 69 |

Spectral data of the synthesized compounds are described below.

10-Chloro-4,12-diphenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine (3a). Yellow solid. Yield 70%. mp. 194–196°C. FT-IR (KBr) ν max (cm−1): 3450.30 (–NH2), 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 2.99 (s, 2H, –CH2), 3.18 (s, 2H, –CH2), 4.43 (s, 2H, –NH2), 7.25 (m, 6H), 7.46 (d, 2H), 7.53 (m, 2H), 7.60–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.99–8.02 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 23.8, 33.8, 118.5, 125.0, 126.2, 127.3, 127.9, 128.3, 128.7, 128.8, 129.2, 129.3, 130.2, 131.1, 132.1, 137.8, 137.9, 146.1, 146.9, 160.4, 160.7, 160.9, 165.5, EI-MS m/z 435.30 [M+1].

10-Chloro-4-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-12-phenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine (3b). Yellow solid. Yield 81%. mp. 218–220°C. FT-IR (KBr) ν max (cm−1): 3446.79 (–NH2), 2931.80–2958.80 (–OCH3). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 3.03–3.06 (m, 2H, –CH2), 3.18–3.21 (m, 2H, –CH2), 3.93-3.94 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 6H, 2-OCH3) 4.34 (s, 2H, –NH2), 6.93–6.95 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 7.23–7.26 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 23.9, 32.8, 55.9, 110.9, 117.2, 117.9, 119.3, 120.2, 120.6, 125.3, 127.5, 127.9, 128.1, 128.4, 128.9, 129.0, 130.1, 130.3, 132.3, 135.0, 138.5, 140.3, 140.7, 144.9, 148.6, 149.3, 157.8, 158.4. EI-MS m/z 495.52 [M+1].

10-Chloro-4-(2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-12-phenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine (3c). White solid. Yield 75%. mp. 212–214°C. FT-IR (KBr) ν max (cm−1): 3485.37 (–NH2), 2931.80–2953.02 (–OCH3). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 2.64 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, –CH2), 2.87 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H, –CH2), 3.14–3.22 (dd, J = 6.8 Hz, J = 17.2 Hz, 2H, –CH2), 3.75–3.79 (d, J = 18.4 Hz, 6H, 2-OCH3), 4.30 (s, 2H, –NH2), 6.89–6.97 (m, 3H), 7.31-7.32 (d, J = 4.8 Mz, 1H), 7.46 (m, 3H), 7.57-7.58 (d, J = 2.4 Mz, 1H), 7.62-7.63 (d, J = 2.4 Mz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.99–8.01 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 23.0, 33.6, 55.8, 56.0, 112.1, 115.4, 115.8, 120.5, 124.9, 126.2, 127.1, 127.8, 128.8, 130.1, 131.0, 131.9, 138.0, 146.0, 146.9, 150.6, 153.7, 159.4, 160.4, 161.2, 163.7. EI-MS m/z 495.35 [M+1].

10-Chloro-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)-12-phenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine (3d). Yellow solid. Yield 69%. mp. 168-170°C. FT-IR (KBr) ν max (cm−1): 3475.73 (–NH2), 2924.73–2960.23 (–OCH3). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 2.39-2.40 (m, 2H, –CH2), 2.71–2.83 (m, 2H, –CH2), 3.82 (s, 3H, –OCH3), 4.83 (s, 2H, –NH2), 6.91 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 6.92-6.93 (s, 1H), 6.97–6.99 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.02–7.04 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.12–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.15 (m, 1H), 7.20–7.22 (m, 2H), 7.24 (m, 2H), 7.31–7.33 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.34–7.36 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 23.7, 33.8, 55.3, 114.1, 115.0, 118.5, 121.1, 124.9, 126.2, 127.2, 127.9, 128.7, 129.3, 129.4, 130.2, 131.1, 132.0, 137.8, 139.3, 146.1, 146.8, 159.5, 160.4, 160.6, 160.9, 165.4 EI-MS m/z 467.31 [M+3].

10-Chloro-4-(4-chlorophenyl)-12-phenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine (3e). White solid. Yield 71%. mp. 210-212°C. FT-IR (KBr) ν max (cm−1): 3495.01 (–NH2), 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 2.97–3.00 (m, 2H, –CH2), 3.18–3.21 (m, 2H, –CH2), 4.35 (s, 2H –NH2), 7.23–7.26 (m, 2H), 7.43–7.51 (m, 7H), 7.60 (d, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 7.64-7.65 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.66-7.67 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 23.8, 33.7, 118.4, 124.8, 126.2, 127.3, 127.9, 128.6, 128.7, 129.3, 130.2, 131.2, 132.1, 135.4, 136.3, 137.7, 146.1, 147.0, 160.4, 160.7, 160.9, 164.3. EI-MS m/z 470.03 [M+1].

10-Chloro-4-(2-chlorophenyl)-12-phenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine (3f). Light yellow. Yield 69%. mp. 238-240°C. FT-IR (KBr) ν max (cm−1): 3481.51 (–NH2), 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 3.12–3.16 (m, 4H, 2-CH2), 5.72 (s, 2H –NH2), 7.26-7.27 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (s, 1H), 7.41–7.44 (m, 1H). 7.46–7.51 (m, 5H), 7.56–7.58 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.79–7.81 (dd, J = 2 Hz, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 8.04–8.06 (d, J = 8.8 Mz, 1H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm), 23.8, 33.7, 118.4, 124.8, 126.2, 127.3, 127.9, 128.6, 128.7, 129.3, 130.2, 131.2, 132.1, 135.4, 136.3, 137.7, 146.1, 147.0, 160.4, 160.7, 160.9, 164.3. EI-MS m/z 469.23 [M+].

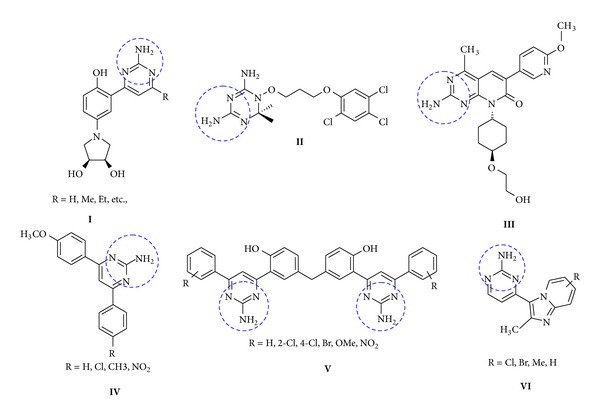

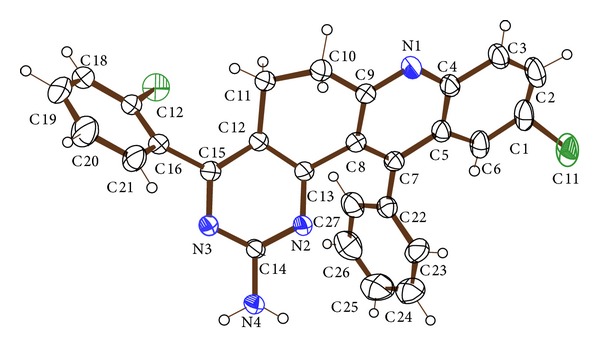

2.4. Single Crystal X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

Crystals suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained by slow evaporation of a solution of the 10-chloro-4-(2-chlorophenyl)-12-phenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine, 3f, in ethyl acetate. The measurements were made on Enraf Nonius CAD4-MV31 single crystal X-ray diffractometer. The diagrams and calculations have been performed using SAINT (APEX II) for frame integration, SHELXTL for structure solution and refinement software programs. The structure was refined using the full-matrix least squares procedures on F2 with anisotropic thermal parameters for all nonhydrogen atoms. The crystal data and details concerning data collection and structure refinement of compound, 3f, single crystal are summarized in Table 2. As we can see compound 3f crystallizes in triclinic space group, P-1. The single crystal structure and atomic numbering chosen for compound 3f are demonstrated in Figure 2. Selected bond lengths and bond angles are compiled in Table 3. It can be observed that the bond lengths of all kind atoms on the whole molecule are absorbed. The typical C–C single (1.55 Å) and C=C double (1.38 Å) bonds, C–N typical single (1.35 Å) and C=N double (1.33 Å) bonds. This means that the carbon-carbon bond and the carbon-nitrogen bond have double bond character and contribute to form conjugated system. Furthermore, carbon attached with strong electronegative atom chlorine bond length is C–Cl (1.68 A), in case all C–H (0.97 A) and C=H (0.93 A) are absorbed. The primary amine hydrogen bond length is N–H (0.86 A), respectively (Table 3). Concerning inspection of the torsion angles, the 3f molecule has nearly planar core. Figure 3 illustrates a representative view of compound 3f crystal packing structure. The two molecules of compound 3f are packed in face-to-face arrangement due to the intermolecular hydrogen bonds. The crystal packing structure demonstrates the existence of two intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Interesting result were absorbed from crystal packing structure is the intermolecular hydrogen bonding occurs at C(23)–H(23) and C(24)–H(24) of one molecule to another neighbouring molecule of C(23)–H(23) and C(24)–H(24), not in the case of primary amine containing two hydrogen N(4)–H(A) and N(4)–H(B) Figure 3.

Table 2.

The crystallographic data and structure refinement parameters of compound 3f.

| Empirical formula | C27 H18 Cl2 N4 |

| Formula weight | 469.35 |

| Temperature | 293(2) K |

| Wavelength | 0.71073 Å |

| Crystal system, space group | Triclinic, P-1 |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 9.9421(5) Å, α = 67.248(2)°. |

| b = 10.9553(5) A, β = 78.530(2)°. | |

| c = 11.5126(5) A, γ = 89.875(2)°. | |

| Volume | 1129.39(9) A3 |

| Z | 2 |

| Calculated density | 1.380 Mg/m3 |

| Absorption coefficient | 0.311 mm−1 |

| F(000) | 484 |

| Crystal size | 0.35 × 0.30 × 0.25 mm |

| Theta range for data collection | 1.96 to 25.00°. |

| Limiting indices | −11 ≤ h ≤ 11, −12 ≤ k ≤ 12, −13 ≤ l ≤ 13 |

| Reflections collected/unique | 19503/3929 [R(int) = 0.0276] |

| Completeness to theta = 25.00 | 98.8% |

| Absorption correction | Semiempirical from equivalents |

| Max. and min. transmission | 0.9635 and 0.8623 |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least squares on F 2 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 3929/6/308 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F 2 | 1.200 |

| Final R indices [I > 2 sigma(I)] | R 1 = 0.0569, wR 2 = 0.1944 |

| R indices (all data) | R 1 = 0.0712, wR 2 = 0.2074 |

| Largest diff. peak and hole | 0.383 and −0.385 e·A−3 |

Figure 2.

ORTEP diagram of compound 3f.

Table 3.

Some important bond lengths (A) and bond angles (°) of compound 3f.

| Bond | Bond length | Bond | Bond angle |

|---|---|---|---|

| C(1)–C(6) | 1.371(6) | N(1)–C(4)–C(5) | 123.2(3) |

| C(2)–H(2) | 0.9300 | N(1)–C(4)–C(3) | 117.1(4) |

| C(11)–H(11A) | 0.9700 | N(1)–C(9)–C(8) | 124.1(4) |

| C(11)–H(11A) | 0.9700 | N(1)–C(9)–C(10) | 116.4(3) |

| C(11)–H(11B) | 0.9700 | C(8)–C(9)–C(10) | 119.4(3) |

| C(11)–H(11B) | 0.9700 | C(9)–C(10)–H(10A) | 109.5 |

| C(13)–N(2) | 1.330(4) | C(11)–C(10)–H(10A) | 109.5 |

| C(14)–N(2) | 1.332(4) | C(12)–C(11)–C(10) | 109.0(3) |

| C(14)–N(3) | 1.344(4) | H(11A)–C(11)–H(11B) | 108.3 |

| C(14)–N(4) | 1.354(4) | C(13)–C(12)–C(15) | 115.8(3) |

| C(15)–N(3) | 1.339(4) | C(15)–C(12)–C(11) | 124.3(3) |

| N(4)–H(4A) | 0.8600 | N(2)–C(13)–C(12) | 123.0(3) |

| N(4)–H(4B) | 0.8600 | N(2)–C(13)–C(8) | 117.8(3) |

| C(4)–N(1) | 1.361(6) | C(12)–C(13)–C(8) | 119.1(3) |

| C(9)–N(1) | 1.317(5) | N(2)–C(14)–N(3) | 126.1(3) |

| C(9)–C(10) | 1.496(6) | N(2)–C(14)–N(4) | 117.0(3) |

| C(10)–C(11) | 1.525(6) | N(3)–C(14)–N(4) | 116.9(3) |

| C(11)–C(12) | 1.508(5) | N(3)–C(15)–C(12) | 122.4(3) |

| C(26)–H(26) | 0.9300 | N(3)–C(15)–C(16) | 116.7(3) |

| C(27)–H(27) | 0.9300 | C(13)–N(2)–C(14) | 116.4(3) |

| C(9)–N(1) | 1.317(5) | C(15)–N(3)–C(14) | 116.2(3) |

| C(1)–Cl(1′) | 1.681(11) | C(14)–N(4)–H(4B) | 120.0 |

| C(1)–Cl(1) | 1.99(4) | H(4A)–N(4)–H(4B) | 120.0 |

| C(17)–Cl(2) | 1.732(4) |

Figure 3.

The packing of the molecules in the unit cell, viewed down the a-axis with the hydrogen bond geometry of compound 3f.

2.5. Glucose Diffusion Inhibitory Test

Sample Preparation. Four different concentrations (100, 200, 300, and 400 μg/mL) of samples were prepared. 1 mL of the sample was placed in a dialysis membrane (12000 MW, Himedia laboratories, Mumbai) along with a glucose solution (0.22 mM in 0.15 M NaCl). Then it was tied at both ends and immersed in a beaker containing 40 mL of 0.15 M NaCl and 10 mL of distilled water. The control contained 1 mL of 0.15 M NaCl containing 0.22 mM glucose solution and 1 mL of distilled water. The beaker was then placed in an orbital shaker. The external solution was monitored every half an hour. Three replications of this test were done for 3 hrs [31, 32].

2.6. Inhibition Assay for α-Amylase Activity

Four different concentrations (100, 200, 300, and 400 μg/mL) of samples and standard drug acarbose were prepared and made up to 1 mL with DMSO. A total of 500 μL of sample and 500 μL of 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9 with 0.006 M NaCl) containing α-amylase solution (0.5 mg/mL) were incubated for 10 minutes, at 25°C. After preincubation, 500 μL of 1% starch solution in 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9 with 0.006 M NaCl) was added to each tube. This reaction mixture was then incubated for 10 minutes at 25°C. 1 mL of DNSA colour reagent was added to stop the reaction. These test tubes were then incubated in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes and cooled to room temperature. Finally this reaction mixture was again diluted by adding 10 mL of distilled water. % of inhibition by α-amylase can be calculated by using the following formula. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm [32, 33]:

| (1) |

Triplicates were done for each sample at different concentrations.

2.7. Inhibition Assay for α-Glucosidase Activity

Various concentrations of samples and standard drug acarbose were prepared. α-Glucosidase (0.075 units) was premixed with sample. 3 mM p-nitrophenyl glucopyranoside used as a substrate was added to the reaction mixture to start the reaction [34]. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and stopped by adding 2 mL of Na2CO3. The α-glucosidase activity was measured by p-nitrophenol release from PNPG at 400 nm. % of inhibition can be calculated by using (1).

Triplicates are done for each sample at different concentrations [31–33].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results are expressed as mean ± SD and n = 3.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Glucose Diffusion Inhibitory Test

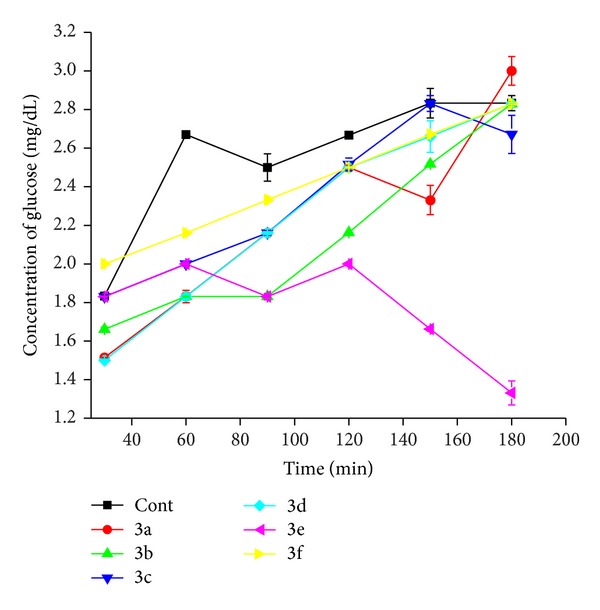

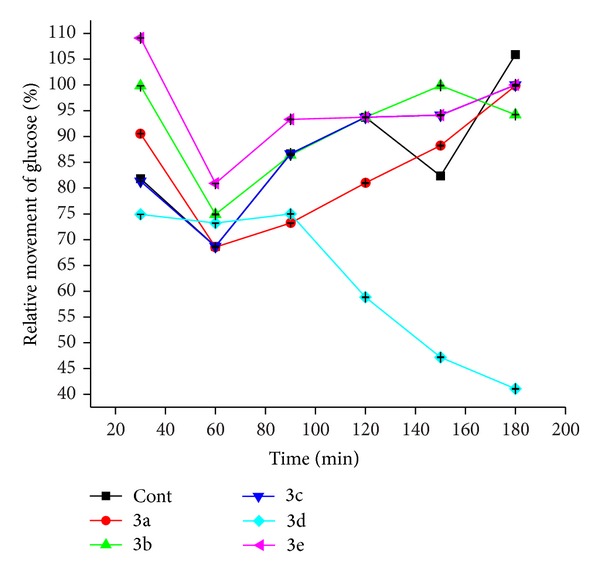

The results are summarized in Tables 4 and 5. The diffused glucose concentration is given in Table 4 and % of relative movement is given in Table 5. The movement of glucose from inside of membrane to external solution monitored and compared in Figures 4 and 5. Among the six samples only the 3e retains the glucose and shows minimum % of relative movement 41.06% over 180 minutes. All other samples show the highest % of relative movement in glucose diffusion from 30 to 180 minutes.

Table 4.

Release of glucose through dialysis membrane to external solution (mg/dL).

| Time (min) | Control | 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | 3e | 3f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 1.833 ± 0.00 | 1.515 ± 0.01 | 1.661 ± 0.00 | 1.830 ± 0.00 | 1.5 ± 0.00 | 1.830 ± 0.00 | 2 ± 0.00 |

| 60 | 2.670 ± 0.03 | 1.831 ± 0.00 | 1.831 ± 0.00 | 2 ± 0.01 | 1.83 ± 0.01 | 2 ± 0.01 | 2.16 ± 0.00 |

| 90 | 2.500 ± 0.00 | 2.161 ± 0.01 | 1.831 ± 0.01 | 2.160 ± 0.00 | 2.16 ± 0.01 | 1.831 ± 0.01 | 2.332 ± 0.07 |

| 120 | 2.667 ± 0.01 | 2.5 ± 0.00 | 2.162 ± 0.03 | 2.515 ± 0.00 | 2.5 ± 0.00 | 2 ± 0.00 | 2.5 ± 0.01 |

| 150 | 2.833 ± 0.07 | 2.331 ± 0.00 | 2.511 ± 0.04 | 2.831 ± 0.08 | 2.66 ± 0.00 | 1.662 ± 0.00 | 2.671 ± 0.07 |

| 180 | 2.833 ± 0.07 | 3 ± 0.00 | 2.830 ± 0.00 | 2.671 ± 0.00 | 2.831 ± 0.06 | 1.331 ± 0.00 | 2.83 ± 0.03 |

Values are mean ± SEM for groups of 3 observations.

Table 5.

% of relative movement in glucose diffusion inhibitory assay.

| Time (min) | 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | 3e | 3f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 81.83 ± 0.01 | 90.56 ± 0.03 | 99.83 ± 0.00 | 81.33 ± 0.00 | 74.90 ± 0.00 | 109.11 ± 0.01 |

| 60 | 68.66 ± 0.07 | 68.53 ± 0.00 | 74.91 ± 0.07 | 68.66 ± 0.01 | 73.20 ± 0.02 | 80.90 ± 0.02 |

| 90 | 86.66 ± 0.05 | 73.20 ± 0.03 | 86.40 ± 0.06 | 86.67 ± 0.02 | 74.99 ± 0.03 | 93.33 ± 0.03 |

| 120 | 93.73 ± 0.04 | 80.99 ± 0.05 | 93.74 ± 0.05 | 93.74 ± 0.05 | 58.83 ± 0.05 | 93.74 ± 0.07 |

| 150 | 82.36 ± 0.01 | 88.24 ± 0.06 | 99.89 ± 0.03 | 94.13 ± 0.06 | 47.18 ± 0.07 | 94.13 ± 0.08 |

| 180 | 105.89 ± 0.02 | 99.84 ± 0.07 | 94.24 ± 0.02 | 100 ± 0.07 | 41.06 ± 0.06 | 100 ± 0.06 |

Values are mean ± SEM for groups of 3 observations.

Figure 4.

Concentration of glucose (mg/dL).

Figure 5.

% of relative movement in glucose diffusion inhibitory assay.

3.1.1. α-Amylase Inhibitory Assay

The results are given in Table 6. All samples show gradual increase in inhibition, where the sample concentration increased from 100 to 400 μg/mL. Sample 3e shows maximum inhibition of 57% and sample 3d shows 23.55% of inhibition. All other samples show varying less significant inhibition.

Table 6.

% inhibition of α-amylase assay.

| Concentration (µg/mL) | Acarbose | 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | 3e | 3f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 32.01 ± 0.09 | 7.97 ± 0.01 | 5.43 ± 0.06 | 3.26 ± 0.00 | 18.83 ± 0.02 | 19.20 ± 0.01 | 12.23 ± 0.00 |

| 200 | 48.15 ± 0.11 | 9.41 ± 0.02 | 5.43 ± 0.02 | 4.34 ± 0.01 | 20.65 ± 0.03 | 21.37 ± 0.00 | 13.77 ± 0.01 |

| 300 | 70.03 ± 0.25 | 11.22 ± 0.07 | 6.52 ± 0.04 | 5.070 ± 0.08 | 21.73 ± 0.01 | 53.62 ± 0.03** | 14.85 ± 0.02 |

| 400 | 80.02 ± 0.71 | 12.31 ± 0.06 | 6.52 ± 0.04 | 6.16 ± 0.06 | 23.55 ± 0.01 | 57.96 ± 0.04 | 16.66 ± 0.03 |

Values are mean ± SEM for groups of 3 observations.

**P < 0.05.

3.1.2. α-Glucosidase Inhibition Assay

The results are shown in Table 7. Among the six samples, 3e shows maximum inhibitory activity of 60.25% at higher concentration (400 μg/mL). Sample 3d shows 23.01% of inhibition. All the other samples are less significant.

Table 7.

% inhibition of α-glucosidase assay.

| Concentration (µg/mL) | Acarbose | 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | 3e | 3f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 30.08 ± 0.05 | 6.02 ± 0.01 | 6.29 ± 0.00 | 4.29 ± 0.01 | 20.91 ± 0.00 | 21.45 ± 0.01* | 14.02 ± 0.02 |

| 200 | 45.02 ± 0.12 | 8.32 ± 0.01 | 7.31 ± 0.02 | 5.02 ± 0.01 | 21.65 ± 0.01 | 24.62 ± 0.09 | 10.77 ± 0.03 |

| 300 | 68.25 ± 0.21 | 10.12 ± 0.01 | 8.01 ± 0.03 | 6.09 ± 0.02 | 22.71 ± 0.02 | 56.85 ± 0.01 | 15.85 ± 0.04 |

| 400 | 78.01 ± 0.07 | 11.45 ± 0.02 | 8.25 ± 0.06 | 9.19 ± 0.02 | 23.01 ± 0.04 | 60.25 ± 0.01** | 17.71 ± 0.03 |

Values are mean ± SEM for groups of 3 observations.

*P < 0.01.

**P < 0.05.

3.2. Molecular Docking Studies

The synthesized molecules 3a–3f were constructed using VEGA ZZ molecular modeling package [35]. The obtained structures were then geometrically optimized using AM1 Hamiltonian in MOPAC software package [36]. The X-ray structure of pig α-pancreatic α-amylase (PDB 3L2M) and N-terminal human maltase-glucoamylase with Casuarina (PDB 3CTT) [37], obtained from Brookhaven Protein Data Bank, were used for docking calculations. Docking calculations were performed with AutoDock 4.0 [38].

The crystal structures were refined by removing water molecules and repeating coordinates. Hydrogen atoms were added and charges were assigned to the protein atoms using Kollman united atoms force field by using AutoDockTools-1.5.6. For docking calculations, Gasteiger partial atomic charges were added to the synthesized structures and all possible flexible torsion angles of the ligand were defined by using AUTOTORS. The structures were saved in a PDBQT format for AutoDock calculations.

AutoDock requires precalculated grid maps, one for each atom type present in the structure being docked. The auxiliary program AutoGrid generated the grid maps. Lennard-Jones parameters 12-10 and 12-6, implemented with the program, were used for modeling H-bonds and van der Waals interactions, respectively. The Lamarckian genetic algorithm method was applied for docking calculations using default parameters. AutoDock uses a semiempirical free energy force field to evaluate conformations during docking simulations. The optimized orientations represent possible binding modes of the ligand within the site:

| (2) |

The first three terms are van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatics, respectively. The term ΔG tor is for rotation and translation and ΔG desolv is for desolvation upon binding and the hydrophobic effect.

After docking, the 50 solutions were clustered into groups with RMS deviations lower than 1.0 Å. The clusters were ranked by the lowest energy representative of each cluster.

3.2.1. Molecular Docking Study on α-Amylase

The binding site of the structures was not identified because of the absence of the crystal structure of the ligand, and a blind docking was performed for all the structures 3a–3f with the protein structure 3L2 M [39]. Two interacting binding sites were identified [37], one near the entrance of the central beta-barrel of the enzyme and the other near the N-terminal of the protein [39]. The docked structures showed binding energy in the range of −4.2 to −4.8 Kcal/mol. It was observed that the structure 3e exhibits high binding energy of −4.8 Kcal/mol and the structure 3d exhibits binding energy of −4.5 Kcal/mol, respectively. The binding energies (ΔG BE) and intermolecular energies (ΔG intermol) of the structures 3d and 3e obtained for α-amylase are given in Table 8. When comparing 3d and 3e structures, 3e exhibits high binding energy. The structure 3e shows interaction with the residues Trp58, Trp59, Tyr62, Asp197, and Asp300 present in the binding site of α-amylase. The amino acids Trp58 and Trp59 were the key residues interacting with all the structures. The docking studies revealed that the van der Waals, electrostatic, and desolvation energies play a key role in binding. It was observed that the Pyrimido ring was fitted well with binding site, via hydrogen bonds through the hydrogen atom of the amino group of 3e with carboxylate group of Asp300. The hydrophobic interactions were formed by Trp58, Trp59, Gln63, Val163, Asp300, His305, and Asp356 in 3e.

Table 8.

The binding energy (ΔG BE) and intermolecular energy (ΔG intermol) of the structures 3d and 3e are given. The docking energy and binding energy are reported in Kcal/mol.

| Structures | ΔG BE | ΔG intermol | ΔG internal | ΔG tor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG vdw_hb_desol | ΔG elec | ||||

| α-Amylase | |||||

| 3d | −4.52 | −5.31 | −0.40 | −1.57 | 1.19 |

| 3e | −4.83 | −5.35 | −0.37 | −1.54 | 0.89 |

|

| |||||

| α-Glucosidase | |||||

| 3d | −6.51 | −6.34 | −1.37 | −1.44 | 1.19 |

| 3e | −6.61 | −6.95 | −0.56 | −1.41 | 0.89 |

3.2.2. Molecular Docking Study on α-Glucosidase

All the binding modes of the structures 3a–3f were explored using the docking calculation in AutoDock. The binding site of the structures was identified using the crystal structure of Casuarina. The docked structures showed binding energy in the range of −6.3 to −6.6 Kcal/mol. The binding energies (ΔG BE) and intermolecular energies (ΔG intermol) of the structures 3d and 3e obtained for α-glucosidase are given in Table 8. The structure 3e showed high binding energy when compared to 3d. Based on docking calculations, the synthesized compounds 3d and 3e show better inhibition of α-glucosidase compared to α-amylase which is in a good agreement with in vitro studies. The following key residues Asp203, Tyr299, Trp406, Asp443, Met444, Phe450, Lys480, Asp542, Phe575, and Gln603 present in the binding site of α-glucosidase show noncovalent interactions with 3e. It was observed that the Pyrimido ring of 3e formed hydrogen bonds through the hydrogen atom of the amino group with carboxylate group of Asp203 at a distance of 1.9 Å. The residues Tyr299, Trp406, Asp443, Met444, Phe450, Lys480, Asp542, Phe575, and Gln603 formed hydrophobic interactions with 3e.

In diabetes mellitus, control of postprandial plasma glucose level is critical in the early treatment [34]. Inhibition of enzymes involved in the metabolism of carbohydrates are one of the therapeutic approaches for reducing postprandial hyperglycemia. The inhibition by natural products is more safe than synthetic drugs.

α-Amylase and α-glucosidase are significant enzymes which cleave carbohydrates responsible for absorption of glucose in the blood stream. For this reason, synthetic drug such as acarbose, miglitol, and voglibose are some inhibitors which inhibit α-amylase and α-glucosidase [40]. However, these agents have their limitations, because they are nonspecific and produce serious side effects such as GI tract inflammation and to elevate diabetic complications [41].

4. Conclusion

The present study revealed that we have successfully achieved our target title compound 10-chloro-4,12-diphenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine derivatives. All compounds were confirmed by suiTable experimental and spectroscopic techniques. Synthesized derivatives (3a–3f) were evaluated in vitroα-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity and glucose diffusion test of samples. Among all other derivatives, compounds 10-chloro-4-(4-chlorophenyl)-12-phenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine, 3e, and 10-chloro-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)-12-phenyl-5,6-dihydropyrimido[4,5-a]acridin-2-amine, 3d, show good inhibitory activity for α-amylase and α-glucosidase with the values of 57.96, 60.27, 23.55, and 23.01% for compounds 3e and 3d, respectively. The docking studies are in good agreement with the in vitro studies. The docking calculations showed that van der Waals, electrostatic, and desolvation energies play a key role in binding. These factors are considered for designing new inhibitors for α-amylase and α-glucosidase.

Supplementary Material

CCDC 988641 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data-request/cif or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033; or e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by DST-SERB Fast Track (Sanction no. SR/FT/CS-264/2012), Government of India, New Delhi. The authors gratefully acknowledge DST-FIST for providing NMR facilities to VIT. The authors acknowledge the support extended by VIT-SIF for GC-MS and NMR analysis.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Milling RJ, Richardson CJ. Mode of action of the anilino-pyrimidine fungicide pyrimethanil. 2. Effects on enzyme secretion in Botrytis cinerea . Pesticidal Science. 2006;45(1):33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu MY, Shi DQ. Synthesis and herbicidal activity of 2-aroxy-propanamides containing pyrimidine and 1, 3, 4-thiadiazole rings. Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 2014;51(2):432–435. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernier JL, Henichart JP, Warin V, Baert F. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of a pyrimido[4,5-d]pyrimidine derivative with antidepressant activity. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1980;69(11):1343–1345. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600691128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong B, Hong F, Kohm C, et al. Synthesis, SAR, and antitumor properties of diamino-C,N-diarylpyrimidine positional isomers: Inhibitors of lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase-β . Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2004;14(9):2303–2308. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong LS, Zhao LX, Choi WJ, et al. Synthesis and antitumor activity of fluorocyclopentenyl-pyrimidines. Nucleosides, Nucleotides, and Nucleic Acids. 2007;26(6-7):713–716. doi: 10.1080/15257770701490852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawser S, Lociuro S, Islam K. Dihydrofolate reductase inhibitors as antibacterial agents. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2006;71(7):941–948. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J, Kim K-H, Jeong S. Discovery of a novel class of 2-aminopyrimidines as CDK1 and CDK2 inhibitors. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2011;21(14):4203–4205. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gadhachanda VR, Wu B, Wang Z, et al. 4-Aminopyrimidines as novel HIV-1 inhibitors. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2007;17(1):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hocková D, Holý A, Masojídková M, et al. 5-Substituted-2,4-diamino-6-[2-(phosphonomethoxy) ethoxy]pyrimidines-acyclic nucleoside phosphonate analogues with antiviral activity. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2003;46(23):5064–5073. doi: 10.1021/jm030932o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rezk BM, Haenen GRMM, Van Der Vijgh WJF, Bast A. Tetrahydrofolate and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate are folates with high antioxidant activity. Identification of the antioxidant pharmacophore. FEBS Letters. 2003;555(3):601–605. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamura T, Hikita A, Ishikawa H, Fujimoto A. Photoinduced amino-imino tautomerization reaction in 2-aminopyrimidine and its methyl derivatives with acetic acid. Spectrochimica Acta A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2005;62(4-5):1157–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie F, Zhao H, Zhao L, Lou L, Hu Y. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel 2,4,5-substituted pyrimidine derivatives for anticancer activity. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2009;19(1):275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones CD, Andrews DM, Barker AJ, et al. Imidazole pyrimidine amides as potent, orally bioavailable cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2008;18(24):6486–6489. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seong Y-S, Min C, Li L, et al. Characterization of a novel cyclin-dependent kinase 1 inhibitor, BMI-1026. Cancer Research. 2003;63(21):7384–7391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vilchis-Reyes MA, Zentella A, Martínez-Urbina MA, et al. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity of 2-methylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine- and quinoline-substituted 2-aminopyrimidine derivatives. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;45(1):379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capdeville R, Buchdunger E, Zimmermann J, Matter A. Glivec (ST1571, imatinib), a rationally developed, targeted anticancer drug. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2002;1(7):493–502. doi: 10.1038/nrd839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kung P-P, Casper MD, Cook KL, et al. Structure-activity relationships of novel 2-substituted quinazoline antibacterial agents. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1999;42(22):4705–4713. doi: 10.1021/jm9903500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh N, Pandey SK, Anand N, et al. Synthesis, molecular modeling and bio-evaluation of cycloalkyl fused 2-aminopyrimidines as antitubercular and antidiabetic agents. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2011;21(15):4404–4408. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh K, Kaur H, Chibale K, Balzarini J, Little S, Bharatam PV. 2-Aminopyrimidine based 4-aminoquinoline anti-plasmodial agents. Synthesis, biological activity, structure-activity relationship and mode of action studies. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;52:82–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagaraj A, Sanjeeva Reddy C. Synthesis and biological study of novel bis-chalcones, bis-thiazines and bis-pyrimidines. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society. 2008;5(2):262–267. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar N, Chauhan A, Drabu S. Synthesis of cyanopyridine and pyrimidine analogues as new anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial agents. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2011;65(5):375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon JH, Park HJ, Chitrapriya N, et al. Effect of number and location of amine groups on the thermodynamic parameters on the acridine derivatives to DNA. The Bulletin of the Korean Chemical Society. 2013;34(3):810–814. [Google Scholar]

- 23.LERMAN LS. The structure of the DNA-acridine complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1963;49:94–102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.49.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubinyi H. Combinatorial and computational approaches in structure-based drug design. Current Opinion in Drug Discovery and Development. 1998;1(1):16–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amuthalakshmi S, Anton Smith A. Insilico design of a ligand for DPP IV in type II diabetes. Advances in Biological Research. 2013;7(6):248–252. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmet PZ. Diabetes epidemiology as a tool to trigger diabetes research and care. Diabetologia. 1999;42(5):499–518. doi: 10.1007/s001250051188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM, Moore PK. Pharmacology Churchill Living Stone. 5th edition 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kandadi MR, Rajanna PK, Unnikrishnan MK, et al. 2-(3,4-Dihydro-2H-pyrrolium-1-yl)-3oxoindan-1-olate (DHPO), a novel, synthetic small molecule that alleviates insulin resistance and lipid abnormalities. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2010;79(4):623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shashikant R, Kekareb P, Ashwini P, Nikaljec A. Studies on the synthesis of novel 2,4-thiazolidinedione derivatives with antidiabetic activity. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2009;5(4):225–230. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subashini R, Bharathi A, Mohana Roopan S, Rajakumar G. Synthesis, spectral characterization and larvicidal activity of acridin-1(2H)-one analogues. Spectrochimica Acta A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2012;95:442–445. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller GL. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Analytical Chemistry. 1959;31(3):426–428. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray AM, Flatt RR. Nature's own pharmacy: the diabetes perspective. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 1997;56(1B):507–517. doi: 10.1079/pns19970051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramírez G, Zavala M, Pérez J, Zamilpa A. In vitro screening of medicinal plants used in Mexico as antidiabetics with glucosidase and lipase inhibitory activities. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/701261.701261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Senthil Kumar P, Sudha S. Evaluation of α-amylase or α-glucosidase inhibitory prosperities of selected seaweeds from gulf of mannar. International Research Journal of Pharmacy. 2012;3(8):128–130. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedretti A, Villa L, Vistoli G. VEGA: an open platform to develop chemo-bio-informatics applications, using plug-in architecture and script programming. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 2004;18(3):167–173. doi: 10.1023/b:jcam.0000035186.90683.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dewar MJS, Zoebisch EG, Healy EF, Stewart JJP. AM1: a new general purpose quantum mechanical molecular model. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1985;107(13):3902–3909. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kashani-Amin E, Larijani B, Habibi AE. Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone, presentation of a small molecule activator of mammalian alpha-amylase as an allosteric effector. FEBS Letter. 2013;587:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, et al. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 1998;19(14):1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu T, Yip YM, Song L, Feng S. Inhibiting enzymatic starch digestion by the phenolic compound diboside A: a mechanistic and in silico study. Food Research International. 2013;54:595–600. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott LJ, Spencer CM. Miglitol: a review of its therapeutic potential in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2000;59(3):521–549. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng AYY, Fantus IG. Oral antihyperglycemic therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Canadian Medicinal Association Journal . 2005;172(2):213–226. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

CCDC 988641 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data-request/cif or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033; or e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk.