Abstract

Aims: β-Lapachone (β-lap), a novel radiosensitizer with potent antitumor efficacy alone, selectively kills solid cancers that over-express NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). Since breast or other solid cancers have heterogeneous NQO1 expression, therapies that reduce the resistance (e.g., NQO1low) of tumor cells will have significant clinical advantages. We tested whether NQO1-proficient (NQO1+) cells generated sufficient hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) after β-lap treatment to elicit bystander effects, DNA damage, and cell death in neighboring NQO1low cells. Results: β-Lap showed NQO1-dependent efficacy against two triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) xenografts. NQO1 expression variations in human breast cancer patient samples were noted, where ∼60% cancers over-expressed NQO1, with little or no expression in associated normal tissue. Differential DNA damage and lethality were noted in NQO1+ versus NQO1-deficient (NQO1−) TNBC cells and xenografts after β-lap treatment. β-Lap-treated NQO1+ cells died by programmed necrosis, whereas co-cultured NQO1− TNBC cells exhibited DNA damage and caspase-dependent apoptosis. NQO1 inhibition (dicoumarol) or H2O2 scavenging (catalase [CAT]) blocked all responses. Only NQO1− cells neighboring NQO1+ TNBC cells responded to β-lap in vitro, and bystander effects correlated well with H2O2 diffusion. Bystander effects in NQO1− cells in vivo within mixed 50:50 co-cultured xenografts were dramatic and depended on NQO1+ cells. However, normal human cells in vitro or in vivo did not show bystander effects, due to elevated endogenous CAT levels. Innovation and Conclusions: NQO1-dependent bystander effects elicited by NQO1 bioactivatable drugs (β-lap or deoxynyboquinone [DNQ]) likely contribute to their efficacies, killing NQO1+ solid cancer cells and eliminating surrounding heterogeneous NQO1low cancer cells. Normal cells/tissue are protected by low NQO1:CAT ratios. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 237–250.

Introduction

According to American Cancer Society, one of every eight women will develop breast cancer in her lifetime, with 180,000 new cases diagnosed each year and a mortality rate of 3% (1). Breast cancers, as with all other cancers, form tumors that are heterogeneous in nature (36). Recent investigations examining the mutational status within different areas of the same tumor identified multiple mutation profiles (28). The exact cause of tumor heterogeneity is hypothesized to be from mutations in different cancer stem-like cell progenitors (26). Tumor heterogeneity presents challenges for many current therapies that specifically target particular types of breast cancer, such as hormone receptor-positive or HER2-positive breast cancers (or both). In general, treatments using more “targeted” drugs, such as Herceptin or the anti-estrogen tamoxifen, are ineffective at killing the entire tumor and select for receptor-negative resistant cancers. These agents should be combined with other chemotherapeutic agents. Future research avenues should develop new chemotherapeutic agents that are capable of killing a variety of heterogeneous cancer cells within the tumor. Ideally, such treatments need to target all tumor cells regardless of mutation status or phenotype, and would have great potential to increase treatment efficacy.

Innovation.

Tumor heterogeneity is a major obstacle for treating individual patients with single agent or combination chemotherapeutics. Our discovery of an NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1)-dependent bystander effect induced by NQO1 bioactivatable drugs suggests a mechanism of action that could augment their tumor-selective lethal properties, enabling synergistic efficacy in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents or ionizing radiation, or for future gene therapy strategies. Elucidating an NQO1-dependent mechanism of action involving hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a mediator opens additional avenues of exploration, particularly for the treatment of solid cancers that have constitutive elevations of NQO1 expression, including pancreatic, nonsmall cell lung, prostate, and breast cancers, especially drug-resistant triple-negative breast cancers.

β-Lapachone (3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-2H-naphthol[1,2-b]pyran-5,6-dione) (β-lap, Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars), a chemotherapeutic agent derived from the bark of the South American Lapacho tree, has recently emerged as a potent antitumor agent that is capable of killing various solid cancers in vitro (6, 10, 32, 40) and in vivo (11, 24). Its mechanism of action is dependent on the enzymatic activity of the two-electron oxidoreductase, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1, EC1.6.99.2), found over-expressed (5- to 100-fold) in most solid cancers, including breast cancer (32, 33). Until recently, delivery issues impeded the agent's use (11, 24), and efficacy against breast cancer xenografts in vivo has not been demonstrated.

NQO1 is an inducible phase II detoxifying enzyme that is capable of reducing quinones by the formation of stable hydroquinones (HQs). Of the thousands of known quinones, only β-lap and deoxynyboquinone (DNQ, see Supplementary Fig. S1) compose an efficacious class of NQO1 “bioactivatable” drugs that are metabolized by NQO1 into unstable HQs. These unstable HQs spontaneously oxidize back to parental compounds, generating a futile redox cycle where >60 moles of NAD(P)H are consumed per mole β-lap in ∼2 min (9, 33). This futile redox cycle results in dramatically elevated levels (∼120 moles/2 min) of superoxide (O2•−) that are quickly metabolized by superoxide dismutase into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (9, 38). The resulting massive H2O2 pool (>500 μM from 4 μM β-lap in 2 h) causes extensive base and single-strand DNA breaks, which, in turn, stimulates poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP1) hyperactivation. Once PARP1 hyperactivation occurs, dramatic NAD+/ATP pool losses ensue, causing DNA repair inhibition (7, 12, 13) and, ultimately, μ-calpain/AIF-mediated programmed necrosis (9). Cancer cells expressing >100 U of NQO1 enzyme activity are killed, while normal tissues that lack, or express low levels of, NQO1 are spared (24). Importantly, the majority of reported cellular effects in β-lap-treated cancer cells are the result of dramatic NAD+/ATP losses and reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation [reviewed in Bentle et al. (5)]. Downstream, μ-calpain and JNK activation (30, 38) in β-lap-exposed NQO1-proficient (NQO1+) cancer cells amplify lethality. μ-calpain activation results in specific atypical PARP1 and p53 proteolyses (33) that culminate in potent AIF-endonuclease G-mediated DNA fragmentation detected by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL)+staining (6, 34). β-Lap-induced lethality and proteolysis are abrogated by dicoumarol (Dic, a specific NQO1 inhibitor), or are absent in cells that are deficient or intentionally knocked down for NQO1 activity (9, 24, 33). Restoration of NQO1 expression in cells knocked down for NQO1 (via stable shRNA or transient siRNA transfections) or in NQO1 polymorphic breast, prostate, pancreatic, or lung cancers restored drug sensitivity (6, 8, 10, 14, 20, 24, 32). Although the mechanism of action of NQO1 bioactivatable drugs (i.e., β-lap, DNQ, and derivatives) is now well defined, the potential for these antitumor agents to stimulate bystander effects has not been reported.

Tumors have heterogeneous gene and protein expression as a result of different rates and types of genetic mutations. Increased mutational and genomic instability results in the genesis of polyclonal tumors with differing levels of sensitivities to a given therapeutic agent or drug combination. Any therapeutic agent that works, in part, through a bystander mechanism of action could bring additional efficacy to cancer treatments. Since H2O2 mediates bystander effect(s) (2), and since copious levels of H2O2 are generated in an NQO1-dependent manner by NQO1 bioactivatable drugs, we hypothesized that the release of cell-permeable H2O2, from NQO1+ breast cancer cells after β-lap or DNQ exposure, would elicit cell death in adjacent NQO1-deficient (NQO1− or NQO1low) cells through a “bystander effect.” While the overall responses would retain NQO1-dependence, proximal NQO1− (NQO1low) cancer cells would be killed, affording efficacious treatment of tumors with heterogeneous NQO1 levels. Here, we demonstrate for the first time the bystander effects in vitro and in vivo caused by these unique NQO1 bioactivatable drugs, such as ARQ761-the clinical form of β-lap.

Results

Antitumor efficacy of β-lap against TNBC subcutaneous xenografts in athymic female mice

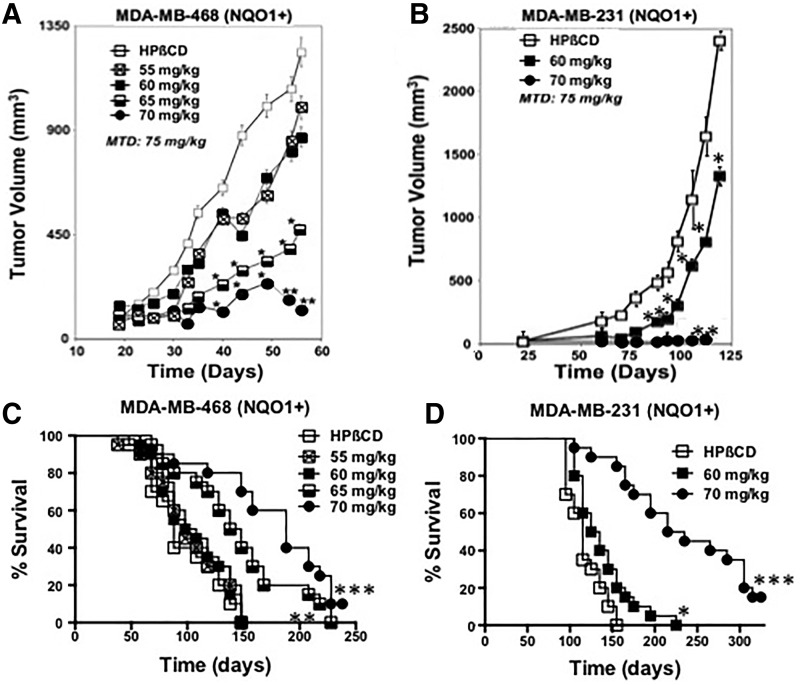

The antitumor efficacy of β-lap was examined using two triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) subcutaneous xenograft models in female athymic mice (18–20 g). The TNBC cell lines, MDA-MB-468 (468) and MDA-MB-231 (231), are *2 NQO1 polymorphic and lack expression of NQO1 mRNA and protein [see Pink et al. (32)]. Each cell line was corrected for NQO1 expression without affecting growth rates in vitro (32). NQO1+ MDA-MB-231 (231NQO1+) or MDA-MB-468 (468NQO1+) cells were used to generate subcutaneous tumors of ∼200 mm3 in the flanks of mice. Mice (five/group, experiments repeated four times) were then intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected every other day for five treatments with hydroxypropyl beta-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) vehicle alone, or indicated β-lap-HPβCD doses as described (11, 14, 20). For i.p. injections, the maximal tolerated dose (MTD) of β-lap-HPβCD was 75 mg/kg. Significant reduction in tumor burden was noted after the administration of 65 mg/kg β-lap-HPβCD, and the most efficacious antitumor effects were noted with 70 mg/kg β-lap-HPβCD in both TNBC models (Fig. 1A, B). In 231NQO1+ xenografts, 60 mg/kg β-lap-HPβCD also showed significant antitumor growth delays compared with HPβCD vehicle alone (Fig. 1B). However, in both TNBC models, 70 mg/kg HPβCD-β-lap treatments resulted in significant antitumor responses that correlated well with overall enhanced survival (Fig. 1C, D). In the 468NQO1+ xenograft model, 10% (2/20) of mice treated with 70 mg/kg β-lap-HPβCD were alive at >200 days post-treatment and were considered “apparently cured” compared with 100% tumor-driven lethality in mice bearing 468NQO1+ tumors treated with HPβCD vehicle alone. Similarly, in the 231NQO1+ xenograft model, 15% (3/20) of tumor-bearing mice treated with 70 mg/kg β-lap-HPβCD were considered “apparently cured” at >280 days post-treatment. Finally, β-lap-treated animals bearing 231NQO1− or 468NQO1− xenografts failed to show significant antitumor growth delays compared with HPβCD vehicle alone treatments, and treated animals were not statistically different (p<0.1) from controls (data not shown). Thus, antitumor efficacy noted with β-lap-HPβCD was dependent on NQO1 expression. Athymic mice simultaneously bearing 231NQO1+ tumors (right flanks) and NQO1− tumors (left flanks) showed similar growth kinetics after treatment with HPβCD alone (p<0.1), while exposure of a similar group of mice to β-lap-HPβCD (70 mg/kg) resulted in significant NQO1-dependent antitumor activity (Supplementary Fig. S2).

FIG. 1.

Antitumor efficacy of β-lap against subcutaneous human TNBC xenografts in athymic mice. (A) Mice bearing 468NQO1+ TNBC xenografts (Ave: ∼200 mm3) were treated with HPβCD (vehicle alone) or β-lap-HPβCD at the indicated mg/kg doses, i.p., every other day for five treatments (see Materials and Methods section). Results (means±SE) are representative of four similar experiments. Student's t-tests (*p≤0.001; **p≤0.0001) were conducted while comparing treated versus control groups. (C) Kaplan–Meier survival curve for 468NQO1+ antitumor efficacy experiments described in (A); log-rank analyses were performed comparing survival curves (**p≤0.005; ***p≤0.0001) for HPβCD versus β-lap-HPβCD at 65 or 70 mg/kg, i.p. Results are combined survival data from four similar experiments. (B) Subcutaneous tumor volume changes in human MDA-MB-231 (NQO1+) TNBC-bearing female athymic nude mice as in (A), except treated groups, i.p., were β-lap-HPβCD at 60 and 70 mg/kg versus HPβCD (*p<0.001; **p<0.0001). (D) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for 231NQO1+ antitumor efficacy experiments described in (C) showed significant (*p≤0.05; ***p≤0.0001) survival advantages of β-lap-HPβCD 60 or 70 mg/kg i.p. treated groups versus HPβCD control. Results are representative of four experiments, each with five mice/group. β-lap, β-lapachone; i.p., intraperitoneal; NQO1+, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1-proficient; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

NQO1 expression in 231NQO1+ TNBC xenografts, and breast cancer versus associated normal tissue from patients

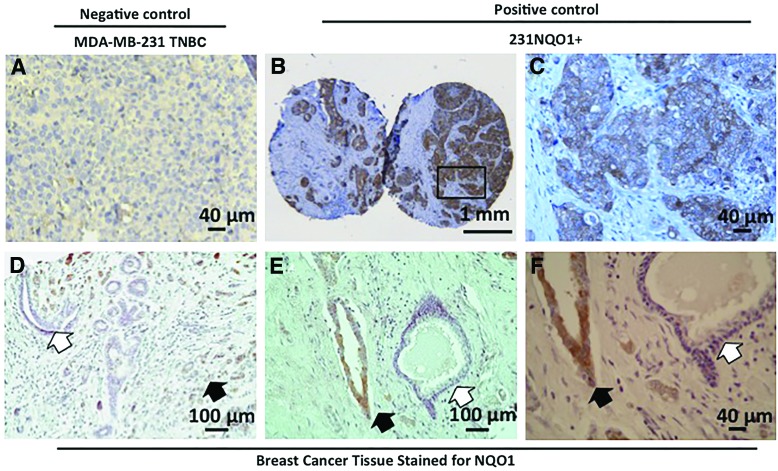

In xenografts derived from 231NQO1+ TNBC cells, NQO1 staining was fairly uniform, although significant heterogeneous regions in NQO1 protein expression were evident (Fig. 2A–C). More importantly, in human breast cancer tissue microarrays, ∼60% (12/20) of breast cancer tissue samples showed strong NQO1 expression, while low to no significant expression was noted in adjacent normal breast tissue (Fig. 2D and Table 1). These data confirmed earlier reports where NQO1 levels were significantly elevated in ∼60% of breast cancers (4, 27). However, in these breast cancer patient samples, significant heterogeneous expression of NQO1 protein levels was noted by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Fig. 2E–F). Based on heterogeneous expression of NQO1 levels in both human TNBC xenografts and human breast cancer patient samples (Fig. 2), and due to the dramatic antitumor efficacy of β-lap (Fig. 1), we examined whether β-lap elicited bystander effects might contribute to the efficacy of this NQO1 “bioactivatable” agent.

FIG. 2.

Histological examination (H&E) and NQO1 expression in 231NQO1+ xenografts and human breast cancer versus associated normal tissue from patients. (A–F) All tissue samples were stained for NQO1 expression. Size of scale bars is indicated. (A) NQO1 staining of NQO1*2 polymorphic NQO1− human MDA-MB-231 xenograft cancer tissue served as a negative control. (B, C) NQO1 staining of a 231NQO1+ xenograft from female athymic mice; (C) is a magnified view of the box in (B). (D–F) NQO1 staining of human breast cancer tissue microarrays. (F) is a magnified view of (E). White arrows: lack of NQO1 staining in associated normal breast tissue. Black arrows: NQO1+ staining in breast cancer cells. NQO1 expression in cancer versus associated normal tissue is summarized in Table 1. NQO1−, NQO1-deficient. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Table 1.

NQO1 Expression in Breast Cancer Tissue Microarrays

| NQO1+ staining | |

|---|---|

| Cancer tissue | 12/20 |

| Surrounding normal tissue | 0/7 |

| Normal | 0/3 |

NQO1, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1; NQO1+, NQO1-proficient.

β-Lapachone generates a bystander effect

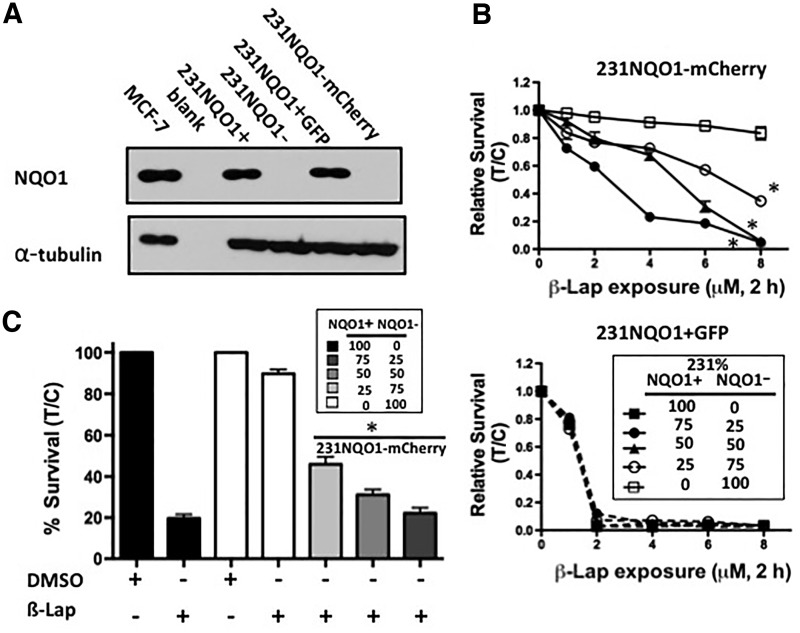

Genetically matched 231NQO1+ and 231NQO1− TNBC cells were stably marked as follows: 231NQO1+ cells were stably transfected with green fluorescence protein (GFP), and 231NQO1− cells were stably transfected with mCherry (red fluorescence protein). The polymorphic statuses of these genetically matched NQO1+ or NQO1− cells were confirmed (Supplementary Fig. S3A, B); MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells are known *2 NQO1 polymorphic, but wild type for the *3 NQO1 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). Western assays confirmed equivalent NQO1 expression in 231NQO1+ and 231NQO1+ TNBC cells transfected with GFP (231NQO1+GFP) (Fig. 3A). In contrast, parental 231NQO1− and 231NQO1− cells stably transfected with mCherry (231NQO1−mCherry) lacked NQO1 expression (Fig. 3A) due to the *2 SNP (Supplementary Fig. S3). Growth rates and plating efficiencies of all 231 cells, regardless of label or NQO1 expression, were identical. 231NQO1+GFP and 231NQO1−mCherry cells were then co-cultured at different ratios, exposed to various β-lap doses, and relative survival levels were determined using an in-plate assay as previously described (32). 231NQO1−mCherry cells were resistant to β-lap unless co-cultured with 231NQO1+GFP cells, and the lethality of NQO1− cells was in direct proportion to the percentage of 231NQO1+GFP cells added (Fig. 3B, upper panel). In contrast, 231NQO1+GFP cells were killed by β-lap in a manner that was independent of how many 231NQO1−mCherry cells were present (Fig. 3B, lower panel). Long-term colony-forming ability assays in sorted cells were confirmed, and were consistent with changes in lethality monitored by relative survival assays. Decreased 231NQO1−mCherry surviving fractions were noted in direct proportion to the percentage of 231NQO1+GFP cells present (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

NQO1-dependent lethality of 231NQO1− cells requires co-culture with 231NQO1+ cells after β-lap treatment. (A) NQO1 expression (31 kDa) was confirmed by western immunoblot analyses in 231NQO1+GFP cells, while absent in 231NQO1−mCherry cells. MCF-7 cells were used as a positive control. Note near identical NQO1 expression in 231NQO1+GFP and parental 231NQO1+ cells. (B) 231NQO1−mCherry and 231NQO1+GFP cells were mixed at indicated ratios, and then treated with various doses of β-lap (μM, 2 h). Survival was separately quantified for 231NQO1−mCherry (upper panel) and 231NQO1+GFP (lower panel) cells. Data are means±SE for three independent experiments performed in triplicate each, (*p≤0.0318 comparing 25:75 NQO1+:NQO1− ratio versus drug-resistant 100% 231NQO1−mCherry survival after β-lap treatment). (C) Colony-forming ability assays were performed under the same conditions as in (B) after β-lap (6 μM, 2 h) treatments (*p≤0.0262 comparing 25:75 NQO1+:NQO1− ratio versus 100% 231NQO1−mCherry). In this 231NQO1+/− cell system where cells were co-cultured at different ratios, 231NQO1+GFP (B, lower panel) cells were normalized to 231NQO1+GFP cells in the untreated control of the corresponding mixed population. Similarly, 231NQO1−mCherry cells (B, upper panel) were normalized to 231NQO1−mCherry cells in the untreated control of the corresponding mixed population. The expression of mCherry and GFP cells was very stable over the duration of the experiment. GFP, green fluorescence protein.

The bystander effect is NQO1 dependent

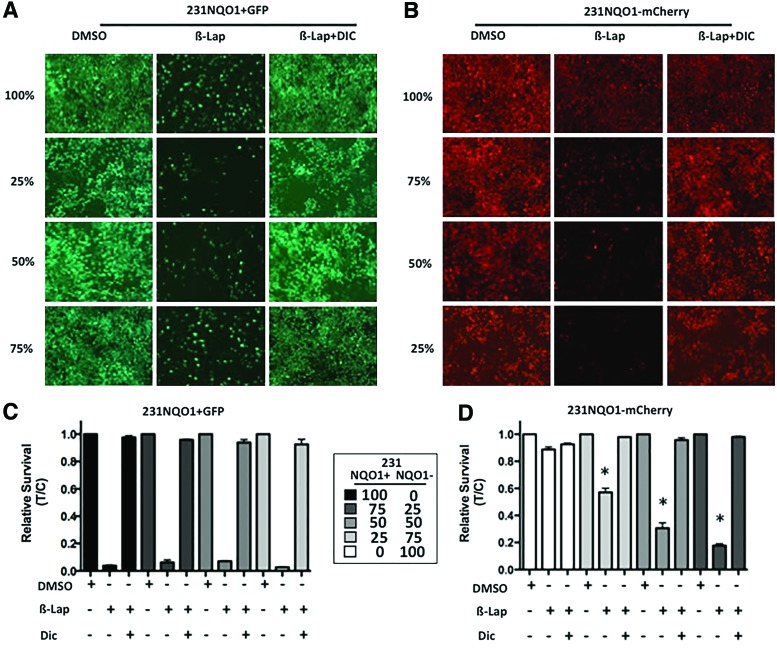

Cell death induced by β-lap was abrogated by co-treatment with the NQO1 inhibitor, Dic, in 231NQO1+GFP cells (Fig. 4A, C) as previously described (6, 32). Similarly, bystander effect lethality induced in 231NQO1−mCherry cells in the presence of 231NQO1+GFP cells (Fig. 4B) was also abrogated by Dic (Fig. 4B, D). When examined alone, 213NQO1−mCherry cells were not responsive to β-lap exposures, with or without Dic (Fig. 4C, D). Thus, the lethalities of 231NQO1−mCherry cells were only noted in the presence of 231NQO1+GFP cells after β-lap treatment, and Dic blocked all bystander effects. These data were strongly consistent with the hypothesis that NQO1 futile redox cycling mediated the bystander effect, producing long-lived and membrane-permeable H2O2 (6).

FIG. 4.

NQO1-dependent lethality of 231NQO1− cells was dependent on the presence of 231NQO1+ cells and blocked by Dic, an NQO1 inhibitor. (A, B) Fluorescent images were simultaneously taken for 231NQO1+GFP (A) or 231NQO1−mCherry (B) cells under different ratios as indicated at 24 h after β-lap (6 μM, 2 h),±Dic treatments. (B, D) Cells were mixed as in (A, C) and then exposed to β-lap (6 μM)±Dic (40 μM) for 2 h, relative survival assessed and graphed for 231NQO1+GFP (C) or 231NQO1−mCherry (D) cells, separately. Data are means±SE for three independent experiments performed in triplicate each, (*p≤0.0437 comparing 25:75 NQO1+:NQO1− ratio versus 100% 231NQO1−mCherry). Dic, dicoumarol. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

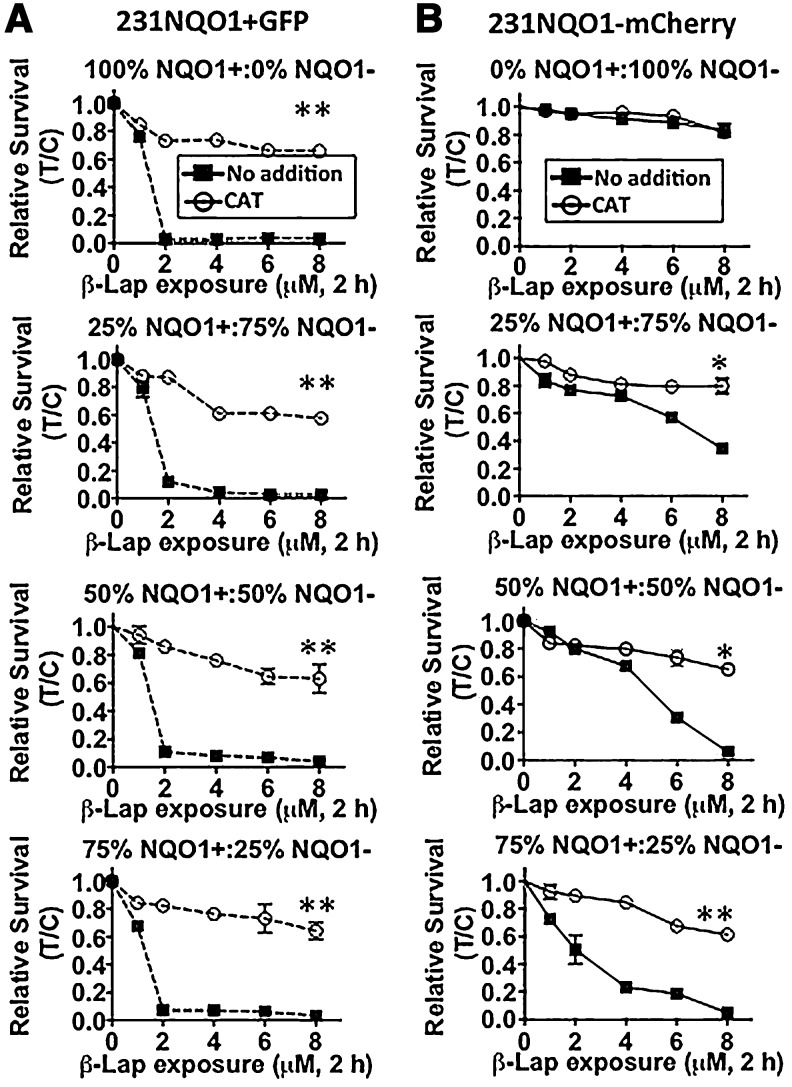

Catalase protects 231NQO1− cells from β-lap-induced bystander effects

We recently demonstrated that exogenous CAT administration could prevent NQO1-dependent cell death in cancer cells in response to NQO1 bioactivatable drug treatments (20). Mixed 231NQO1−mCherry and 231NQO1+GFP co-cultures were, therefore, treated with exogenous CAT. 231NQO1+GFP cells were spared from cell death when CAT was added, due to the blockage of H2O2 accumulation and downstream DNA damage responses (DDRs) (Fig. 5A–B) as reported (9). Similarly, 231NQO1−mCherry cells showed progressively increased lethality in direct proportion to increased co-cultured percentages of 231NQO1+GFP cells, completely spared by exogenous CAT (2000 U) addition (Fig. 5E–G). The cytoprotective effects of CAT were similar regardless of the percentages of 231NQO1+GFP cells added (Fig. 4A, B), suggesting that H2O2 was the obligate ROS that mediated bystander effect-induced lethality in 231NQO1−mCherry cells, lethality dependent on the presence of 231NQO1+GFP in co-cultures.

FIG. 5.

CAT protects both 231NQO1+ and 231NQO1− mixed co-cultured cells from lethality caused by β-lap. Various co-culture mixtures of (A) 231NQO1+GFP and (B) 231NQO1−mCherry cells were made as indicated (top to bottom panels), respectively, and were as follows: 100:0; 25:75; 50:50; and 75:25 213NQO1+GFP:231NQO1−mCherry, respectively. Cells were then exposed to β-lap (6 μM)±CAT (2000 U) for 2 h, and relative survival levels were determined for 231NQO1+GFP (left panel set) and 231NQO1−mCherry (right panel set) cells. Data represent means±SE of three independent experiments, with each performed in triplicate. *p≤0.05. **p≤0.01, for CAT-treated versus untreated. CAT, catalase

We hypothesized that the dose of H2O2 experienced during a bystander effect by 231NQO1−mCherry cells would be fundamentally lower, resulting in DDRs, formation of poly(ADP-ribosylated) protein (PAR formation) due to normal repair (and not PARP1 hyperactivation), and cell death by caspase-mediated responses, than in NQO1+ cells. Genetically matched 231NQO1+ and 231NQO1− TNBC cells treated with varying doses of H2O2 showed no difference in cell survival (Supplementary Fig. S4, p=0.8112); however, when treated with low doses of β-lap, only 231NQO1+ cells were responsive (Supplementary Fig. S4), illustrating the NQO1-dependent nature of β-lap lethality. From the H2O2 dose-response survival curve (Supplementary Fig. S4), we estimate that ∼20 μM exogenous H2O2 was equivalent (LD50) to ∼1.5 μM β-lap in 231NQO1+ cells (compare Fig. 3B to Supplementary Fig. S4). However, these cells undergo caspase-dependent apoptosis after exposure to exogenous 20 μM H2O2 (35%±7% TUNEL+staining measured separately). In contrast, the same 231NQO1+ cells exposed to 1.5 μM β-lap die by a unique μ-calpain-dependent programmed necrotic cell death pathway (6, 9, 38), illustrating a fundamentally different NQO1-dependent mechanism of cell killing caused by the bystander effect. Indeed, to mimic β-lap-induced programmed necrosis seen in NQO1+ cells, 231NQO1−mCherry cells required an exposure of ≥300 μM exogenous H2O2 as previously reported (6, 9, 38).

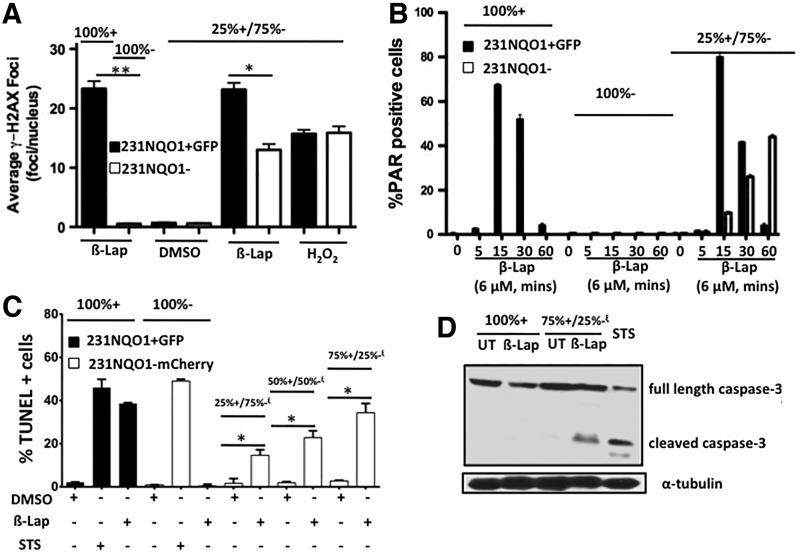

The β-lap-induced bystander effect causes caspase-dependent cell death

To monitor DDRs during β-lap-induced bystander effects in 231NQO1− cells, γ-H2AX foci formation (a result of activated DNA damage sensors, ATM, and DNA-PK) (7) and PAR formation (a result of PARP1 hyperactivation or normal DNA repair processes that can be differentiated by overall levels formed in the nucleus by confocal microscopy) (18, 22) were monitored. In β-lap-treated co-cultures, 231NQO1− cells exhibited a low level of γ-H2AX foci/nuclei, but only when neighboring 231NQO1+GFP cells were present. Bystander effects elicited in NQO1− cells were accompanied by considerably less DNA damage (γ-H2AX foci/nucleus formed) than in co-cultured 231NQO1+GFP cells after β-lap treatments (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, co-cultured normal IMR-90 cells were spared from bystander effects when mixed with 231NQO1+GFP cells, presumably due to their relatively high catalase (CAT) levels and lower NQO1/CAT ratio (0.045) compared with 231NQO1−mCherry cells (NQO1:CAT ratio: 1.2, Supplementary Fig. S5A). As demonstrated in various NQO1+ cancer cells (6, 8, 14, 20), robust and extensive PAR formation occurred within 15 min in 231NQO1+ TNBC cells after β-lap exposure and dissipated within 60 min due to concomitant NAD+/ATP losses and retained poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) activity (8, 20). These responses were independent of co-culture conditions (see solid bars for 100% or co-cultured 231NQO1+GFP cells, Fig. 6B). In contrast, in 231NQO1− cells undergoing a bystander effect (caused by nearby 231NQO1+GFP cells), PAR formation showed a normal PAR formation-related DNA repair pattern that gradually increased in levels from 5 to 60 min corresponding to drug exposure, levels consistent with normal DNA repair processes over time (17) (see open bars in 25%:75% mixed co-cultures, Fig. 6B). 231NQO1− cells were not responsive to β-lap treatments, with no detectable PAR-PARP1 formation in the absence of NQO1+ cells (Fig. 6B). β-Lap-induced bystander effects in 231NQO1−mCherry cells were accompanied by apoptosis (increased TUNEL+staining) in direct proportion to the number of 231NQO1+GFP cells present (Fig. 6C). In the absence of 231NQO1+GFP cells in co-culture, γ-H2AX foci (Fig. 6A), PAR formation (Fig. 6B), and TUNEL+staining (Fig. 6C) were not noted in β-lap-exposed 231NQO1−mCherry cells. 231NQO1+GFP cells exposed to β-lap resulted in delayed (compared with more immediate formation noted after ionizing radiation) (6) γ-H2AX formation (Fig. 6A) (20), intense and immediate PAR formation (Fig. 6B) (20), and TUNEL+staining indicative of PARP1 hyperactivation-mediated programmed necrosis (8, 14, 20, 24). Thus, the kinetics and extent of PAR formation coupled with TUNEL+staining strongly suggested a cell death pathway mediated by classical caspase-dependent apoptosis. Indeed, 231NQO1−mCherry cells undergoing bystander effects in the presence of β-lap-treated 231NQO1+GFP cells died by classical apoptosis with cleaved caspase-3 proteolysis (Fig. 6D), which is absent during NQO1-dependent PARP1 hyperactivation-induced programmed necrosis noted in NQO1+ TNBC cells (6, 8, 9, 32). 231NQO1−mCherry cells were also treated with staurosporine (STS, 1 μM, 12 h) as a positive control that induces caspase-dependent apoptosis (39). β-Lap-treated 231NQO1+GFP cells were TUNEL+, but they lacked cleaved caspase-3 as reported (8, 9), in processes that are not affected by zVAD or DVED addition (9). In contrast, 231NQO1−mCherry cells isolated from a mixed population with 231NQO1+GFP co-culture showed significant caspase-3 cleavage, correlating well with TUNEL+staining (Fig. 6D). Thus, 231NQO1−mCherry cells undergoing β-lap-induced bystander effects in co-culture with 231NQO1+ TNBC cells die by caspase-3-dependent apoptosis, while β-lap-exposed 231NQO1+GFP cells die by PARP1 hyperactivation-mediated, caspase-independent programmed necrosis as previously described (6, 8, 38).

FIG. 6.

DDR- and caspase-dependent cell death accompany 231NQO1− TNBC cells undergoing a bystander effect that was dependent on the presence of 231NQO1+ cells. (A) DDR responses monitored by γ-H2AX foci/nucleus were counted and quantified 30 min after treatment with 6 μM β-lap by confocal microscopy in 100% 231NQO1+GFP alone, in 100% 231NQO1− alone, or in a 25% 231NQO1+GFP:75% 231NQO1− mixed ratio. The average number of γ-H2AX foci/nucleus was determined from ≥60 cells for each treatment group from three independent confocal experiments, performed in duplicate. *p≤0.05; **p≤0.005. (B) Assessment of PAR formation in 100% 231NQO1+GFP alone, 100% 231NQO1− alone, or in a 25% 231NQO1+GFP:75% 231NQO1− mixed ratio during exposure to 6 μM β-lap for 5–60 min. Quantified percentages of PAR+cells from confocal microscopy analyses of ≥60 cells from four independent experiments, repeated in duplicate. Graphed are means±SE (C) 231NQO1+GFP and 231NQO1−mCherry cells were mixed in different ratios as indicated and exposed to β-lap (6 μM, 2 h). Cells were harvested at 48 h, sorted based on GFP or mCherry expression by FACS, and cell death was monitored by TUNEL+staining. Average TUNEL+means±SE were graphed from two independent experiments performed in triplicate. TUNEL+cells can arise from programmed necrosis in 231NQO1+GFP cells, or apoptosis in 231NQO1−mCherry cells dependent on 231NQO1+GFP cells. Student's t-tests were conducted while comparing sorted 231NQO1−mCherry cells in β-lap-treated mixed group with DMSO control (*p≤0.01). (D) Western blots show differential caspase-3 cleavage patterns. Full-length inactive caspase-3 is 32 kDa, whereas active caspase-3 is present in two cleaved forms (i.e., 17 and 16 kDa fragments). Note the lack of cleaved caspase-3 in β-lap-treated 100% 231NQO1+GFP cells as previously described (9, 32), whereas 231NQO1−mCherry cells within the 75%+/25%− mixed co-cultured cells showed significant caspase-3 cleavage/activation. 231NQO1−mCherry cells treated with STS (1 μM, 12 h) was used as a positive control for activating caspase-3. DDR, DNA damage response; STS, staurosporine; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling.

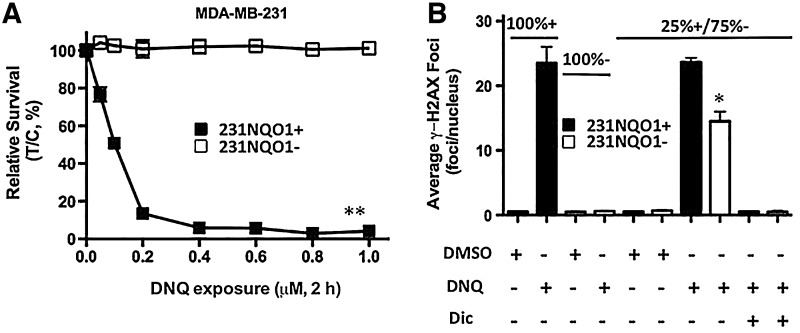

Bystander effects induced by DNQ

DNQ is a more potent NQO1 bioactivatable drug (20). DNQ-induced cell death was NQO1 dependent with 231NQO1+ cells showing significant lethality, while 231NQO1− cells were resistant to the drug. DNQ killed NQO1+ cells with ∼10-fold greater potency than β-lap (0.2 μM DNQ vs. 2 μM β-lap, respectively) (Fig. 7A). As with β-lap, DNQ treatment (0.4 μM) caused significant γ-H2AX foci/nucleus formation in 231NQO1− cells, but only when co-cultured, and spatially near, 231NQO1+ cells. DNQ (0.4 μM) was equivalent to 6 μM β-lap treatment in terms of mediating a bystander effect in 231NQO1− cells (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

DNQ-induced NQO1-dependent bystander effects on 231NQO1− cells. (A) DNQ kills 231 TNBC cells in an NQO1-dependent manner. 231NQO1+ or 231NQO1− cells were exposed to various DNQ concentrations (μM, 2 h) as indicated, and relative survival levels were determined. Graphed are means±SE of three independent experiments, with each performed in triplicate. **p≤0.01. (B) DNQ elicits NQO1-dependent DDR responses in 231NQO1− cells that are dependent on the presence of 231NQO1+ cells. 231NQO1+, 231NQO1−, or a 25% 231NQO1+:75% 231NQO1− (25%+/75%−) co-culture of cells were quantified for a DDR monitored by γ-H2AX foci/nucleus formation at 30 min during a DNQ (0.4 μM) treatment, with or without Dic. Average γ-H2AX foci/nucleus values were determined from ≥60 cells per treatment group from three independent confocal experiments, with each performed in duplicate. *p≤0.0115 for 231NQO1− cells in co-culture compared with drug-resistant β-lap-treated 231NQO1− cells alone or co-cultured β-lap-exposed 231NQO1− cells co-treated with Dic. DNQ, deoxynyboquinone.

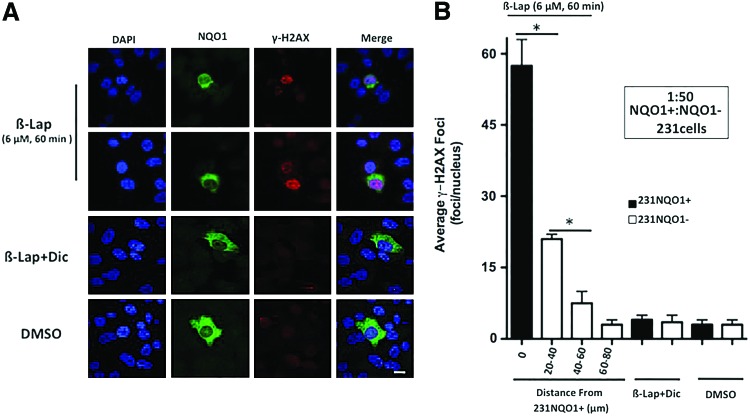

The β-lap-induced bystander effect follows the inverse-square law, consistent with diffusible H2O2 as a mediator

A 1:50 ratio of 231NQO1+:231NQO1− cells were treated with 6 μM β-lap±Dic (50 μM) for 60 min, fixed, and simultaneously stained for NQO1 expression and γ-H2AX foci formation. Nonlabeled cells were used in these experiments. By confocal microscopy, 231NQO1+ cells showed significant γ-H2AX foci formation (≥50 foci/nucleus) that was easily distinguished from adjacent 231NQO1− cells in response to β-lap (see representative images, Fig. 8A). NQO1+ staining confirmed the presence of 231NQO1+ cells in the co-culture, while 231NQO1− cells lacked NQO1 expression (Fig. 8A). Adjacent 231NQO1− cells exhibited DDRs, with elevated γ-H2AX foci/nucleus formation, after β-lap treatment. As the distance from 231NQO1+ cells increased, fewer γ-H2AX foci/nucleus in 231NQO1− cells were noted (Fig. 8B). Since the diameter of a 231 cell nucleus ranged between 15 and 22 μm, we categorized adjacent 231NQO1− cells into three groups according to their estimated distance (in μm) from a central 231NQO1+ cell. These groups were defined by distance ranging from a central 231NQO1+ cell in the co-culture: (i) 20–40 μm, (ii) 40–60 μm, and (iii) 60–80 μm. While untreated or β-lap-exposed 231NQO1− cells alone (without NQO1+ cell co-culture) exhibited basal levels of γ-H2AX formation (2–4 foci/nucleus), NQO1−231 cells in the group 20–40 μm from an NQO1+231 cell center averaged 15–17 γ-H2AX foci/nuclei (p≤0.002 compared with β-lap-exposed 231NQO1− cells alone, and p<0.005 vs. 231NQO1+ cells). In NQO1−231 cells 40–60 μm from an NQO1+231 cell center, five to seven γ-H2AX foci/nucleus were counted (p≤0.005 compared with NQO1−231 cells within the 20–40 μm group; p<0.01 with regard to β-lap-treated 231NQO1− cells without NQO1+ cell co-culture). However, in the group 60–80 μm, only three to five γ-H2AX foci/nuclei were detected, levels that were not statistically different from untreated or β-lap-exposed 231NQO1− cells alone (Fig. 8B). Dic blocked all DDRs in 231NQO1+ cells and 231NQO1− cells that were co-cultured with 231NQO1+ cells (Fig. 8B). Thus, DDRs (by γ-H2AX foci/nucleus) were formed in an NQO1-dependent manner in 231NQO1− cells, requiring neighboring 231NQO1+ cells (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, the bystander effect created by a single 231NQO1+ TNBC cell affected only nearby adjacent NQO1− cells and dissipated in a manner consistent with the inverse square of distance law, consistent with H2O2 diffusion (21).

FIG. 8.

γ-H2AX foci/nucleus formation in bystander 231NQO1− cells depends on co-cultured 231NQO1+ cells and dissipates by the square-distance law. (A) Confocal microscopy visualization of DAPI stained nuclei, NQO1 expression, and punctuate γ-H2AX foci/nucleus in a mixed 1:50 ratio of 231NQO1+:231NQO1− cells, respectively, after treatment with either DMSO (0.01%) or β-lap (6 μM)±Dic (50 μM) for 60 min. Cells were stained for DNA content by DAPI, NQO1 expression, and γ-H2AX foci formation. Data were analyzed separately and merged. (B) Co-culture experiments were performed as in (A), and the average number of γ-H2AX foci/nucleus (means±SE) was determined from ≥60 231NQO1+ “cell centers” for three different groups. Distance ranges from a central 231NQO1+ cell in the co-culture defined these groups: (i) 20–40 μm; (ii) 40–60 μm; and (iii) 60–80 μm, assuming that an average 231 cell nucleus was ∼22 μm. Data (means±SE) were from three independent confocal experiments, with each performed in duplicate. *p≤0.0376. Bar, 20 μm. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

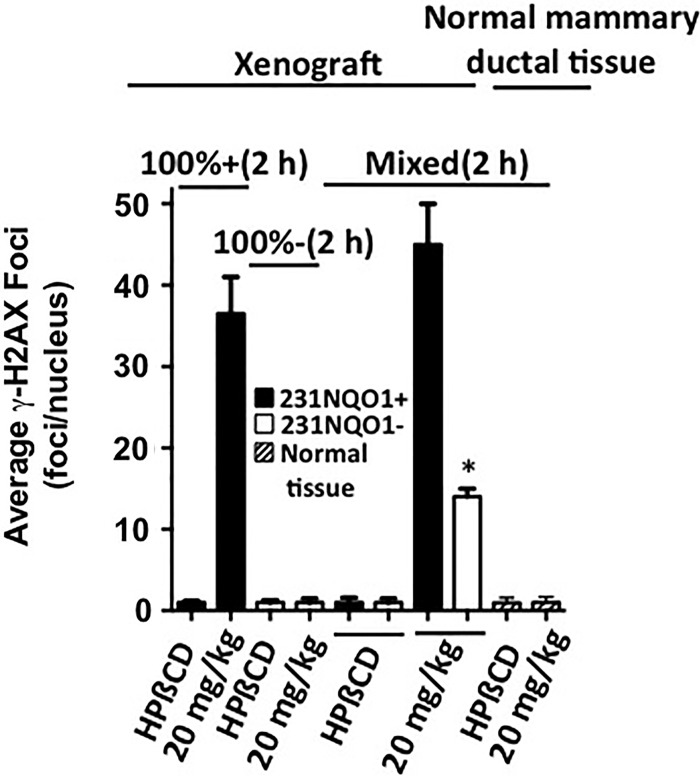

β-Lapachone induces NQO1-dependent bystander effects in vivo

Orthotopic xenografts of mixed 231NQO1+GFP and 231NQO1−mCherry cells were used to demonstrate β-lap-mediated bystander effects in vivo. Orthotopic xenografts composed of 100% 231NQO1+GFP or 100% NQO1−mCherry cells were used as controls. Animals were then exposed to β-lap-HPβCD (20 mg/kg, intravenously [i.v.]), and DDRs were assessed 2 h later. Unlike xenografts composed of 100% 231NQO1−mCherry cells, which showed no increase in DDRs above basal levels (1–3 γ-H2AX foci/nuclei) after exposure to β-lap-HPβCD, 231NQO1−mCherry cells within 50:50 mixed cell orthotopic xenografts exhibited γ-H2AX foci/nuclei formation ranging from 13 to 15 foci/nuclei, a statistically significant (p=0.0254) 4- to >10-fold increase after treatment compared with basal levels or levels noted in xenografts composed of 100% NQO1−231 cells after β-lap treatment in vivo. Robust γ-H2AX foci formation (ranging from 32 to 50 foci/nucleus) within 2 h was noted in 231NQO1+GFP cells within the co-cultured xenograft after an i.v. injection of 20 mg/kg β-lap-HPβCD, whether or not 231NQO1−mCherry cells were present within the orthotopic xenografts. Importantly, normal mammary ductal breast epithelial cells within the same 50:50 mixed cell xenografts, and characterized by normal glandular structures, had low γ-H2AX formation (one to three foci/nuclei), with or without exposure to 20 mg/kg β-lap-HPβCD (Supplementary Fig. S6 and Fig. 9).

FIG. 9.

β-Lapachone induces an NQO1-dependent bystander effect in vivo. Female NOD/SCID mice bearing 100% 231NQO1+GFP alone, 100% 231NQO1−mCherry alone, or 50% 231NQO1+GFP:50% 231NQO1−mCherry mixed ratio 231 xenografts (Ave: ∼200 mm3) in fat pads were treated with HPβCD (vehicle alone) or β-lap-HPβCD (20 mg/kg) i.v. (see Materials and Methods section). DDR responses (γ-H2AX foci/nucleus) were assessed and quantified 2 h post-treatment by confocal microscopy. The average number of γ-H2AX foci/nucleus was determined from ≥60 cells for each treatment group from three independent fat pad xenografts, performed in duplicate. Normal mammary ductal cells were also identified within xenograft areas, and γ-H2AX foci/nuclei were assessed. These normal tissues were NQO1low and lacked DDRs (i.e., showed basal levels of γ-H2AX foci/nuclei) after treatment with β-lap-HPβCD. *p=0.0254. i.v., intravenously.

Discussion

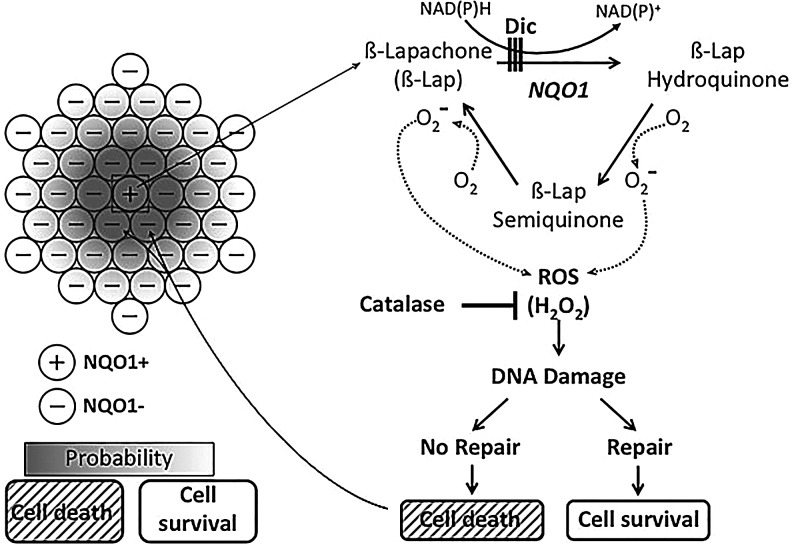

The ability to tailor chemotherapy and/or targeted therapies to individual patients is a major objective in cancer therapy due to extensive heterogeneity within individual tumors and between patients. β-Lap is a highly specific antitumor agent, and its anticancer effects are dependent on NQO1 expression. NQO1 is a flavoprotein that is overexpressed approximately 5- to 200-fold compared with normal adjacent tissue in various solid tumors, including cancers of the pancreas, lung, prostate, and breast (14, 23, 27). However, heterogeneous NQO1 expression and enzyme activity in clinical tumors has not been considered in detail. We observed variations in NQO1 expression in human xenografts in athymic nude mice derived from cell lines (Fig. 2), possibly suggesting some level of epigenetic regulation. In humans, two NQO1 polymorphisms (NQO1*2 C609T and NQO1*3 C465T) exist at ∼5%–10%, depending on race and rendering such individuals NQO1−. The NQO1*2 polymorphism, present in both MDA-MB-468 and MDA-MB-231 TNBCs, represents a rare genotype in TNBCs with unstable mRNA and lack of NQO1 protein expression (31). Patients with these polymorphisms are detected using restriction fragment-length polymorphism (RFLP) assays from blood (35). Both 231 and 468 NQO1*2 polymorphic cells were used to create genetically matched NQO1+ and NQO1− models (32, 34, 39). Since NQO1 is overexpressed at the same relative percentage (∼60%) in all breast cancer subtypes, including TNBCs, we initiated this work to examine the antitumor efficacy of β-lap against human breast cancers. The β-lap-HPβCD formulation used in this study is essentially the same as ARQ761, which is in a current phase Ib clinical trial in the US (www.clinicaltrials.gov). While significant antitumor efficacy was noted (Fig. 1), it occurred very close to the MTD of this formulation (Fig. 1). While nanotechnology-based delivery systems greatly improve the therapeutic window of these drugs (11), we hypothesized that a bystander effect within NQO1+ tumors may contribute to the dramatic dose-dependent improvement of antitumor efficacy noted between 60 and 70 mg/kg β-lap-HPβCD treatments (Fig. 1). Earlier studies from our lab showed no noticeable signs of systemic toxicity by these β-lap exposures using H&E staining of normal tissue throughout the body, and, in particular, target organs in the liver and kidney, where NQO1 levels are the highest (<10 U) (15). Histological examination of 231NQO1+ xenografts, and especially human patient tumor versus associated normal breast tissues showed heterogeneity for NQO1 expression. Using a co-culture model system in vitro composed of 231NQO1+ and 231NQO1− cells, either alone or combined at different ratios, we observed clear evidence of a bystander effect resulting from the release of H2O2 from 231NQO1+ cells. NQO1 inhibition (by Dic) blocked β-lap-induced lethality and DDRs in NQO1+ cells, and it also prevented bystander effects in neighboring NQO1−231 co-cultured cells (Fig. 10). CAT, an enzymatic H2O2 scavenger, was able to detoxify H2O2 generated in the cytoplasm of NQO1+ cells (9), thereby preventing H2O2 diffusion to adjacent 231NQO1− cells. CAT likely plays an important role in the protection of normal cells from such bystander effects (Supplementary Fig. S5). In vivo, γ-H2AX formation in 231NQO1−mCherry cells in a mixed xenograft with 231NQO1+GFP cells demonstrates a bystander effect that is consistent with results observed in vitro. The lack of DNA damage in normal breast tissue (Fig. 9) is likely the result of low NQO1 and high CAT expression, protecting them from H2O2 generated from 231NQO1+GFP cells.

FIG. 10.

Model of β-lap-induced, NQO1-dependent bystander DDR and lethality effects occurring in NQO1+/NQO1− mixed co-cultures. Utilizing NAD(P)H as electron donors, NQO1 performs a two-electron oxidoreduction of β-lap, forming its unstable HQ form, but avoiding enzymes that perform one-electron oxidoreductions and forming the SQ. Dic, an NADH analog NQO1 inhibitor, binds NQO1 ahead of the quinone given the enzyme's ping-pong bye-bye mechanism of quinone detoxification. The β-lap HQ spontaneously reverts to its parental oxidized compound. Each back reaction consumes two moles of molecular oxygen. This partial reduction and spontaneous reversion of β-lap result in the release of a large burst of superoxide, which is rapidly converted to H2O2 by superoxide dismutase. Large increases of cell-permeable H2O2 cause extensive single base and single-strand DNA lesions in the nucleus by fenton reactions, ultimately leading to PARP1 hyperactivation and programmed necrosis in NQO1+ cells, such as 231NQO1+ and 468NQO1+ TNBC cells (32). Since the half life of superoxide is ∼1×10−15 s, H2O2, which has a much longer half life of 1–2 s. and is permeable to cell membranes, it can diffuse readily from cell to cell and impact neighboring NQO1− cells, such as co-cultured 231NQO1− cells. If the concentration of H2O2 in adjacent NQO1− cells is sufficiently high, cell death will occur through a typical caspase-dependent mechanism, resulting in bystander-induced DDR responses and apoptosis. CAT, an enzymatic H2O2 scavenger, is able to detoxify both the H2O2 generated in the cytoplasm of the NQO1+ cells (9) and the more dilute (due to the square-distance law) H2O2 that has diffused into adjacent NQO1− cells. Thus, H2O2 is the obligate ROS mediating the NQO1-dependent bystander effect caused by NQO1 bioactivatable drugs, such as β-lap and DNQ. Data in this article suggest that the maximum diffusion distance for H2O2 to enable lethality of neighboring 231NQO1− cells is limited to ∼40–60 μm, when NQO1+ cell centers are surrounded by NQO1− cells. However, additive effects are clearly noted in xenografts (Fig. 9), where all NQO1− cells demonstrated some bystander effects. H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; HQ, hydroquinone; PARP1, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SQ, semiquinone.

Although both responses to β-lap were NQO1 dependent, DDRs and lethality caused by a bystander effect in 231NQO1− cells were vastly different from cell death noted in co-cultured 231NQO1+ cells. Earlier data showed that β-lap-induced cell death and lethality in NQO1+ cancer cells was accompanied by >80%–90% loss of NAD+/ATP within 1 h (38) caused by PARP1 hyperactivation (6, 8, 20, 38). Accordingly, peak PAR formation in β-lap-treated NQO1+ cells occurred within 15 min and dissipated by 60 min, a result of concomitant NAD+ loss (PARP1 substrate) and PARG activity (9, 14). In contrast, β-lap-exposed 231NQO1− cells undergoing a bystander effect from neighboring 231NQO1+ cells showed gradual increases in PAR formation from 5 to 60 min, indicative of normal DNA repair kinetics in response to ROS damage to DNA. These cells also stained TUNEL+, showed distance-dependent (with regard to 231NQO1+ cells) DDRs and cell death, culminating in caspase-3 cleavage and activation in a classical apoptotic pathway. Different cell death mechanisms are stimulated by β-lap depending on the level of acute intracellular concentrations of H2O2. PARP1 hyperactivation results in 231NQO1+ cells due to massive amounts of ROS generated by the futile redox cycle (Fig. 10), and profound depletion of NAD+/ATP causes programmed necrosis. In contrast, the H2O2-mediated bystander effect elicits activation of normal DNA repair pathways in 231NQO1− cells due to moderate amounts of ROS, typically leading to apoptosis, in which DNA damage falls short of a critical threshold of DNA lesions required for PARP1 hyperactivation. These cells typically die by replicative stress or senescence.

Evidence accumulated over the past two decades has shown bystander effects for gene therapy (16, 25), ionizing radiation (3), chemotherapy, and H2O2 (2). This is the first report of a bystander effect induced by NQO1 bioactivatable drugs, including β-lap and DNQ. Evidence of a bystander effect opens new perspectives for improved therapy of β-lap and potentially other NQO1 bioactivatable drugs.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

β-Lapachone (3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-2H-naphthol[1,2-b]pyran-5,6-dione) was synthesized, dissolved in DMSO and concentrations were verified by spectrophotometric analyses (40). β-Lap stocks were stored at −80°C and used once. HPβCD (>98% purity) was obtained from Cyclodextrin Technologies Development, Inc. (Alachua, FL) and prepared as previously described (29). Dic, CAT, STS, and H2O2, were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). DNQ was supplied by Dr. Paul Hergenrother (University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign, Champaign, IL) and prepared as previously described for β-lap (20).

Cell culture

Human MDA-MB-231 (231) and MDA-MB-468 (468) TNBC cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and contained C609T NQO1*2 polymorphisms (35), rendering them NQO1−. Cells (231 and 468) were corrected for NQO1 expression (32, 34). 231NQO1+ cells were stably transfected with GFP (231NQO1+GFP). Genetically matched 231NQO1− cells were stably transfected with mCherry (231NQO1−mCherry). Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (33) and intermittently selected in geneticin (G418, 400 μg/ml) (40), but all experiments were performed without antibiotics. Tissue culture supplies were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), unless otherwise stated. Cells were routinely tested and were free of mycoplasma contamination.

Relative survival assays

Relative survival assays based on GFP or mCherry signals on a single plate were performed as previously described (32). Briefly, 231NQO1+GFP or 231NQO1−mCherry cells were plated in the following ratios: 0:100, 25:75, 50:50, 75:25, and 100:0 for NQO1+:NQO1−, respectively, at 4.0×104 cells per six-well dishes. After incubation overnight, co-cultured cells were treated with or without various β-lap concentrations,±Dic (50 μM) or±CAT (2000 U) for 2 h. Fresh media were added, and cells were allowed to grow for 5–7 days. Photomicrographs of cells were then taken (5× Mag. at λ=488 nm for GFP and λ=594 nm for mCherry). Cell numbers instead of fluorescence intensity were quantified from five photos by NIH ImageJ software. Earlier studies demonstrated that relative survival assays correlated well with long-term colony-forming assays for β-lap and DNQ (20, 32). Data were expressed as treated/control (T/C, means±SE) for three separate experiments repeated in triplicate. Groups were compared using two-tailed Student's t-tests for paired samples.

Colony-forming assays

Clonogenic assays were performed after a 6–7-day growth period, or >50 normal-appearing cells per colony were noted in controls (12). Data were graphed as means±SE, and statistical analyses were performed using Student's t-tests. Each experiment was performed twice, in triplicate.

Confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy was performed as previously described (6, 7, 39). Control or treated cells were fixed in methanol/acetone (70%/30%) and incubated with α-PAR (10H; Alexis, San Diego, CA), α-γ-H2AX (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD), or α-NQO1 (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) antibodies for 1 h, room temperature. Nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining, and images were collected at λ=488/594 nm excitation for GFP/mCherry, respectively, from a krypton/argon laser using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Thornwood, NY). Images are representative of experiments performed at least four times in duplicate. The number of PAR+ and γ-H2AX foci/nucleus (means±SE) was quantified by counting ≥60 cells from four experiments.

Cell sorting and TUNEL assay

231NQO1−mCherry or 231NQO1+GFP cells were collected from a mixed population by sorting using an MoFlo Beckman Coulter FACS (Fort Collins, CO) and TUNEL staining. Briefly, mixed cells were centrifuged in Ca2+/Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline on ice and treated with DNAse (10 U/ml) to prevent clumping. NQO1−mCherry or 231NQO1+GFP cells (∼0.1×106) were sorted from cells treated with or without β-lap, fixed with paraformaldehyde (100% alcohol permeation), and stored at −20°C until analyzed. Apoptotic populations were assessed using TUNEL assays and flow cytometry (FC-500 flow cytometer; Beckman Coulter Electronics) (25). Each experiment was performed twice, in triplicate.

Immunoblotting

Western blot analyses were performed using whole-cell extracts as previously described (40) with modifications. Sorted 231NQO1−mCherry cells were obtained as described earlier and monitored for NQO1, caspase-3 proteolysis, and α-tubulin using antibodies at 1:500 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) or 1:5000 (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) dilutions as indicated. The NQO1 antibody was generously provided by Dr. David Ross (University of Colorado Health Science Center, Denver, CO) and used at a 1:2000 dilution (37).

NQO1 polymorphism analyses

Polymerase chain reaction–RFLP (PCR-RFLP) analyses of the NQO1 gene for *2 and *3 polymorphisms were performed using PCR amplification with the primer set of 5′-TCCTCAGAGTGGCATTCTGC-3′ and 5′-TCTCCTCATCCTGTACCTCT-3′ (for *2) or 5′-TCAAGTTGGCTGACCAAGGACA-3′ and 5′-CCTGCATCAGTACAGACCAC-3′ (for *3). The amplified PCR products were then digested with either Hinf-1 (for NQO1*2) or Msp-1 (for NQO1*3) and analyzed using electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel.

Antitumor efficacy

Subcutaneous breast cancer xenograft models in female athymic mice (18–20 g) were used to evaluate the efficacy of β-lap-HPβCD. Briefly, breast tumors were initiated by injecting 1×107 468NQO1+ or 231NQO1+ cells into the flanks of animals (11). After 2–3 weeks, tumors were measured using calipers, and mice were randomized into groups (five animals/group). When tumor volumes were ∼200 mm3, mice were treated with HPβCD vehicle alone or indicated doses of β-lap-HPβCD every other day for five total injections (i.e., one regimen) (11). Tumor growth was monitored by volume measurements over time. Mice were sacrificed when tumor burden reached 10% overall body weight. Tumor volume data were graphed as means±SE, and overall survival was graphed by Kaplan–Meier protocols from three separate studies (11). An orthotopic fat pad injection model was used to evaluate the bystander effect of β-lap in vivo as previously described (19). Briefly, 231NQO1+GFP and 231NQO1−mCherry cells were implanted into the mammary fat pad of female NOD/SCID mice (18–20 g) to evaluate the bystander effect of β-lap-HPβCD in vivo. Mice were randomized into five animals per group and 1×107 100% 231NQO1+GFP alone, 100% 231NQO1−mCherry alone, or 50% 231NQO1+GFP:50% 231NQO1−mCherry mixed ratio 231 cells were surgically implanted into each mammary fat pad. When xenografts were ∼200 mm3, mice were treated with HPβCD vehicle alone or 20 mg/kg β-lap-HPβCD i.v. and euthanized 2 h post-treatment. Tumor was collected and snap frozen for further immunofluorescence use. All animal studies were performed as per UT Southwestern (A3472-01) IACUC approved (01/11/2013) animal protocol (2008-0108).

Histological staining

Archived formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue from clinically annotated, surgically resected breast cancer specimens containing tumor and adjacent normal epithelial tissues were obtained from the Simmons Cancer Center Tissue Management Shared Resource, and used to construct the breast cancer tissue microarray (9) for immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining as previously described (14). For TNBC xenografts in Figure 2, control tumors were fixed in 10% formalin overnight, paraffin embedded, and processed by the Department of Pathology, UT Southwestern Medical Center. Sections (5-μm-thick) were H&E stained and also stained for NQO1 expression. Histological images were taken using a Nikon E400 microscope with a Nikon Coolpix 4500 camera as previously described (14). Cryosections for snap frozen tumor tissue were sectioned, ethanol fixed, rehydrated, and stained for immunofluorescence using α-γ-H2AX (Cell Signaling Technology) and α-NQO1 (Abcam) antibodies at 1 h, room temperature. Nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining, and images were collected at λ=488/594 nm excitation for NQO1/α-γ-H2AX, respectively, using a krypton/argon laser attached to a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Thornwood, NY). Data were quantified from three or more xenografts.

Statistical analyses

Tumor growth profiles in two tested groups were analyzed using a mixed model approach. Log-rank tests were applied to Kaplan–Meier survival curves. p-Values of ≤0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with the SAS 9.1.3 Service Pack 3 (11, 14, 20, 24).

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- 231

MDA-MB-231

- 468

MDA-MB-468

- 231NQO1+

MDA-MB-231-NQO1-proficient

- 231NQO1−

MDAMB-231-NQO1-deficient

- 468NQO1+

MDA-MB-468-NQO1-proficient

- 231NQO1−mCherry

MDA-MB-231-NQO1-deficient-mCherry;

- 231NQO1+GFP

MDAMB-231-NQO1-proficient-GFP

- β-lap

β-lapachone (3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-2H-naphthol[1,2-b]pyran-5,6-dione)

- CAT

catalase

- DDR

DNA damage response

- Dic

dicoumarol

- DNQ

deoxynyboquinone

- GFP

green fluorescence protein

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HQ

hydroquinone

- IHC

immunoshistochemistry

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.v.

intravenously

- MTD

maximal tolerated dose

- NQO1

NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1

- NQO1+

NQO1-proficient

- NQO1−

NQO1-deficient

- PARG

poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase

- PARP1

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RFLP

restriction fragment-length polymorphism

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SQ

semiquinone

- STS

staurosporine

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to the work and life of Rosemarie Bouley, to whom the authors are eternally grateful for her support and inspiration. They thank Xiuquan Luo and Carlos Gil Del Alcazar for their helpful discussions and technical support. This research was supported by NIH/NCI grant 5 R01 CA102792 to D.A.B. The authors acknowledge the small animal imaging, flow cytometry, and Tissue Management Shared Resource Cores from NCI/NIH grant# 5P30 CA14253 to the Simmons Cancer Center. This is CSCN #072.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society report: Cancer Facts & Figures. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2013, www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-036845.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexandre J, Hu Y, Lu W, Pelicano H, and Huang P.Novel action of paclitaxel against cancer cells: bystander effect mediated by reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res 67: 3512–3517, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Azzam EI, Toledo SM, and Little JB. Oxidative metabolism, gap junctions and the ionizing radiation-induced bystander effect. Oncogene 22: 7050–7057, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belinsky M. and Jaiswal AK. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 (DT-diaphorase) expression in normal and tumor tissues. Cancer Metastasis Rev 12: 103–117, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentle MS, Bey EA, Dong Y, Reinicke KE, and Boothman DA. New tricks for old drugs: the anticarcinogenic potential of DNA repair inhibitors. J Mol Histol 37: 203–218, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentle MS, Reinicke KE, Bey EA, Spitz DR, and Boothman DA. Calcium-dependent modulation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 alters cellular metabolism and DNA repair. J Biol Chem 281: 33684–33696, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentle MS, Reinicke KE, Dong Y, Bey EA, and Boothman DA. Nonhomologous end joining is essential for cellular resistance to the novel antitumor agent, beta-lapachone. Cancer Res 67: 6936–6945, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bey EA, Bentle MS, Reinicke KE, Dong Y, Yang CR, Girard L, Minna JD, Bornmann WG, Gao J, and Boothman DA. An NQO1- and PARP-1-mediated cell death pathway induced in non-small-cell lung cancer cells by beta-lapachone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 11832–11837, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bey EA, Reinicke KE, Srougi MC, Varnes M, Anderson VE, Pink JJ, Li LS, Patel M, Cao L, Moore Z, Rommel A, Boatman M, Lewis C, Euhus DM, Bornmann WG, Buchsbaum DJ, Spitz DR, Gao J, and Boothman DA. Catalase abrogates beta-lapachone-induced PARP1 hyperactivation-directed programmed necrosis in NQO1-positive breast cancers. Mol Cancer Ther 12: 2110–2120, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanco E, Bey EA, Dong Y, Weinberg BD, Sutton DM, Boothman DA, and Gao J. Beta-lapachone-containing PEG-PLA polymer micelles as novel nanotherapeutics against NQO1-overexpressing tumor cells. J Control Release 122: 365–374, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanco E, Bey EA, Khemtong C, Yang SG, Setti-Guthi J, Chen H, Kessinger CW, Carnevale KA, Bornmann WG, Boothman DA, and Gao J. Beta-lapachone micellar nanotherapeutics for non-small cell lung cancer therapy. Cancer Res 70: 3896–3904, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boothman DA, Greer S, and Pardee AB. Potentiation of halogenated pyrimidine radiosensitizers in human carcinoma cells by beta-lapachone (3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-2H-naphtho[1,2-b]pyran-5,6-dione), a novel DNA repair inhibitor. Cancer Res 47: 5361–5366, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boothman DA, Trask DK, and Pardee AB. Inhibition of potentially lethal DNA damage repair in human tumor cells by beta-lapachone, an activator of topoisomerase I. Cancer Res 49: 605–612, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong Y, Bey EA, Li LS, Kabbani W, Yan J, Xie XJ, Hsieh JT, Gao J, and Boothman DA. Prostate cancer radiosensitization through poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase-1 hyperactivation. Cancer Res 70: 8088–8096, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong Y, Chin SF, Blanco E, Bey EA, Kabbani W, Xie XJ, Bornmann WG, Boothman DA, and Gao J. Intratumoral delivery of beta-lapachone via polymer implants for prostate cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 15: 131–139, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman SM, Abboud CN, Whartenby KA, Packman CH, Koeplin DS, Moolten FL, and Abraham GN. The “bystander effect”: tumor regression when a fraction of the tumor mass is genetically modified. Cancer Res 53: 5274–5283, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottipati P, Vischioni B, Schultz N, Solomons J, Bryant HE, Djureinovic T, Issaeva N, Sleeth K, Sharma RA, and Helleday T. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is hyperactivated in homologous recombination-defective cells. Cancer Res 70: 5389–5398, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassa PO, Haenni SS, Elser M, and Hottiger MO. Nuclear ADP-ribosylation reactions in mammalian cells: where are we today and where are we going? Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70: 789–829, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiraga T, Williams PJ, Mundy GR, and Yoneda T. The bisphosphonate ibandronate promotes apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells in bone metastases. Cancer Res 61: 4418–4424, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang X, Dong Y, Bey EA, Kilgore JA, Bair JS, Li LS, Patel M, Parkinson EI, Wang Y, Williams NS, Gao J, Hergenrother PJ, and Boothman DA. An NQO1 substrate with potent antitumor activity that selectively kills by PARP1-induced programmed necrosis. Cancer Res 72: 3038–3047, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapner DJ, Cook TS, Adelberger EG, Gundlach JH, Heckel BR, Hoyle CD, and Swanson HE. Tests of the gravitational inverse-square law below the dark-energy length scale. Phys Rev Lett 98: 021101, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim MY, Zhang T, and Kraus WL. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP-1: ‘PAR-laying’ NAD+into a nuclear signal. Genes Dev 19: 1951–1967, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis AM, Ough M, Hinkhouse MM, Tsao MS, Oberley LW, and Cullen JJ. Targeting NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) in pancreatic cancer. Mol Carcinog 43: 215–224, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li LS, Bey EA, Dong Y, Meng J, Patra B, Yan J, Xie XJ, Brekken RA, Barnett CC, Bornmann WG, Gao J, and Boothman DA. Modulating endogenous NQO1 levels identifies key regulatory mechanisms of action of beta-lapachone for pancreatic cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 17: 275–285, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S, Tokuyama T, Yamamoto J, Koide M, Yokota N, and Namba H. Bystander effect-mediated gene therapy of gliomas using genetically engineered neural stem cells. Cancer Gene Ther 12: 600–607, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Polyak K, Brisken C, Yang J, and Weinberg RA. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 133: 704–715, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marin A, Lopez de Cerain A, Hamilton E, Lewis AD, Martinez-Penuela JM, Idoate MA, and Bello J. DT-diaphorase and cytochrome B5 reductase in human lung and breast tumours. Br J Cancer 76: 923–929, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marusyk A. and Polyak K. Tumor heterogeneity: causes and consequences. Biochim Biophys Acta 1805: 105–117, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nasongkla N, Wiedmann AF, Bruening A, Beman M, Ray D, Bornmann WG, Boothman DA, and Gao J. Enhancement of solubility and bioavailability of beta-lapachone using cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. Pharm Res 20: 1626–1633, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park MT, Song MJ, Lee H, Oh ET, Choi BH, Jeong SY, Choi EK, and Park HJ. beta-lapachone significantly increases the effect of ionizing radiation to cause mitochondrial apoptosis via JNK activation in cancer cells. PLoS One 6: e25976, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips RM, Burger AM, Fiebig HH, and Double JA. Genotyping of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) in a panel of human tumor xenografts: relationship between genotype status, NQO1 activity and the response of xenografts to Mitomycin C chemotherapy in vivo(1). Biochem Pharmacol 62: 1371–1377, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pink JJ, Planchon SM, Tagliarino C, Varnes ME, Siegel D, and Boothman DA. NAD(P)H:Quinone oxidoreductase activity is the principal determinant of beta-lapachone cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem 275: 5416–5424, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pink JJ, Wuerzberger-Davis S, Tagliarino C, Planchon SM, Yang X, Froelich CJ, and Boothman DA. Activation of a cysteine protease in MCF-7 and T47D breast cancer cells during beta-lapachone-mediated apoptosis. Exp Cell Res 255: 144–155, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinicke KE, Bey EA, Bentle MS, Pink JJ, Ingalls ST, Hoppel CL, Misico RI, Arzac GM, Burton G, Bornmann WG, Sutton D, Gao J, and Boothman DA. Development of beta-lapachone prodrugs for therapy against human cancer cells with elevated NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 levels. Clin Cancer Res 11: 3055–3064, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross D, Kepa JK, Winski SL, Beall HD, Anwar A, and Siegel D. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1): chemoprotection, bioactivation, gene regulation and genetic polymorphisms. Chem Biol Interact 129: 77–97, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Argani P, Weremowicz S, Bloushtain-Qimron N, Yao J, Nikolskaya T, Serebryiskaya T, Beroukhim R, Hu M, Halushka MK, Sukumar S, Parker LM, Anderson KS, Harris LN, Garber JE, Richardson AL, Schnitt SJ, Nikolsky Y, Gelman RS, and Polyak K. Molecular definition of breast tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Cell 11: 259–273, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegel D, Franklin WA, and Ross D. Immunohistochemical detection of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase in human lung and lung tumors. Clin Cancer Res 4: 2065–2070, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tagliarino C, Pink JJ, Dubyak GR, Nieminen AL, and Boothman DA. Calcium is a key signaling molecule in beta-lapachone-mediated cell death. J Biol Chem 276: 19150–19159, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tagliarino C, Pink JJ, Reinicke KE, Simmers SM, Wuerzberger-Davis SM, and Boothman DA. Mu-calpain activation in beta-lapachone-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Biol Ther 2: 141–152, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wuerzberger SM, Pink JJ, Planchon SM, Byers KL, Bornmann WG, and Boothman DA. Induction of apoptosis in MCF-7:WS8 breast cancer cells by beta-lapachone. Cancer Res 58: 1876–1885, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.