Abstract

Defining the biologic roles of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOS) requires an efficient, simple, reliable, and robust analytical method for simultaneous quantification of oligosaccharide profiles from multiple samples. The HMOS fraction of milk is a complex mixture of polar, highly branched, isomeric structures that contain no intrinsic facile chromophore, making their resolution and quantification challenging. A liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) method was devised to resolve and quantify 11 major neutral oligosaccharides of human milk simultaneously. Crude HMOS fractions are reduced, resolved by porous graphitic carbon HPLC with a water/acetonitrile gradient, detected by mass spectrometric specific ion monitoring, and quantified. The HPLC separates isomers of identical molecular weights allowing 11 peaks to be fully resolved and quantified by monitoring mass to charge (m/z) ratios of the deprotonated negative ions. The standard curves for each of the 11 oligosaccharides is linear from 0.078 or 0.156 to 20 μg/mL (R2 > 0.998). Precision (CV) ranges from 1% to 9%. Accuracy is from 86% to 104%. This analytical technique provides sensitive, precise, accurate quantification for each of the 11 milk oligosaccharides and allows measurement of differences in milk oligosaccharide patterns between individuals and at different stages of lactation.

Keywords: Oligosaccharides, Human Milk, LC-MS

Introductory Statement

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOS) are the third largest component, with typical concentrations between 6 to 12 g/L; levels in colostrum are reported at 20 g/L and more [1]. HMOS are composed of D-glucose (Glc), D-galactose (Gal), N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), L-fucose (Fuc), and sialic acid (N-acetyl neuraminic acid, Neu5Ac, NANA). The core structures of HMOS consist of a reducing end of lactose and a variable core of GlcNAc 1,3 or 1,4 linkages alternating with 1,3 or 1,4 Gal [2]. This multiplicity of polylactosamine core structures vary further by attachment of Fuc (1,2; 1,3; or 1-4 linkages), and/or NANA (by 2,3; or 2,6 linkages) to the core structures [3]. Those terminating in sialic acid comprise the bulk of the acidic oligosaccharides in human milk; most of the neutral oligosaccharides of human milk are fucosylated. The structures of well over one hundred distinct oligosaccharides have been defined [3], and many more are thought to exist [4].

HMOS are essentially indigestible by human intestinal mucosa, suggesting a role for infants other than nutrition: Human milk oligosaccharides may protect breastfed infants from disease [5; 6]. HMOS promote colonization of human gut by beneficial bacteria [7; 8]. HMOS also competitively inhibit the essential first step for enteric infection, adhesion of pathogenic microbes to mucosal epithelial cells [3; 9]. HMOS may modify glycan expression by human intestinal mucosal cells, reducing their affinity for pathogenic microbes [10].Protection by human milk glycans is highly dependent upon specific glycan structural motifs, whose expression and concentrations vary by maternal glycosyltransferase genotypes and by the stage of lactation. Thus, individual human milk samples differ in their ability to protect the infant [11; 12].

An essential prerequisite for studying biologic roles of human milk oligosaccharides is a quantitative method suitable for analysis of multiple HMOS in large numbers of samples. However, the oligosaccharide fraction of human milk is a large complex mixture of molecules that are very polar, many are highly branched, contain multiple structural isomers, and no intrinsic chromophore, presenting a challenge to both their resolution and quantitative detection. HPLC is most commonly used in the analysis of oligosaccharides [13-24], with some capillary electrophoresis (CE) as well [25-28]. Derivatives of neutral oligosaccharides can be separated on both normal phase [15] and reversed-phase columns, followed by quantification by their UV absorbance [13; 16; 18; 20]. For analysis of underivatized oligosaccharides, a common method is resolution by high-pH anion-exchange chromatography with detection by pulsed amperometry [17; 19; 21-24]. Underivatized acidic oligosaccharides or derivatized neutral oligosaccharides have also been resolved by ion exchange HPLC with detection at 200 nm absorbance [14]. However, these HPLC methods typically require time-consuming sample preparation, significant amounts of sample, and, most importantly, afford only incomplete resolution and poor sensitivity due to the high degree of structural complexity and isomerism of the oligosaccharides. Moreover, the lack of structural discrimination by UV detection can make identification of peaks ambiguous.

Porous graphitic carbon (graphite) is increasingly used as a versatile stationary phase [29]. The chemical nature and physical structure of the graphite allow unique retention and separation of very polar compounds. The surface of this graphitic carbon is stereo-selective with the ability to resolve geometric isomers and other closely related compounds. In addition, this solid phase is stable throughout the entire pH range of 1-14 and is not affected by aggressive mobile phases. Solvents and additives used for elution from graphitic columns are similar to those of traditional HPLC; many are MS compatible. LC-MS with a graphite column combines the separation power of graphite with the sensitivity and structure discrimination of MS, allowing their use in analyzing carbohydrates [30-33], peptides [34], nucleosides [35], drugs [36-39], and pesticides [40]. Other types of columns can separate oligosaccharides, but their use in LC-MS has been limited to qualitative analysis of carbohydrates [41-45]. Herein, a general LC-MS method for the simultaneous quantification of 11 human milk oligosaccharides was developed and validated. After reduction by sodium borohydride, 11 alditol forms of oligosaccharides resolved well on a graphitic carbon column and detected by MS; this technique allows high-throughput and is suitable for routine analysis of large numbers of milk samples.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Authentic reference standards 2′-fucosyllactose (2′-FL), 3-fucosyllactose (3-FL), lacto-N-tetraose (LNT), lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT), lacto-N-fucopentaose I (LNFP-I), lacto-N-fucopentaose II (LNFP-II), lacto-N-fucopentaose V (LNFP-V), lacto-N-fucopentaose VI (LNFP-VI), lacto-N-difucohexaose I (LNDH-I), and lacto-N-difucohexaose II (LNDFH-II) were obtained from Glycoseparations (Moscow, Russia). Authentic lacto-N-fucopentaose III (LNFP-III) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Structures of the above 11 neutral oligosaccharides are shown in Table 1. Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and acetonitrile (CH3CN), acetic acid (HOAc), and ethanol (EtOH) were from Thermo Fisher Scientific. MilliQ deionized water was used in this study.

Table 1.

Structures of the eleven human milk oligosaccharides.

| Abbreviation | Trivial name | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| 2′-FL | 2′-Fucosyllactose | Fucα1-2Galβ1-4Glc |

| 3-FL | 3-Fucosyllactose | Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)Glc |

| LNT | Lacto-N-tetraose | Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-3 Galβ1-4Glc |

| LNnT | Lacto- N -neotetraose | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3 Galβ1-4Glc |

| LNFP-I | Lacto-N-fucopentaose I | Fucal-2Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-3 Galβ1-4Glc |

| LNFP-II | Lacto-N-fucopentaose II | Galβ1-3(Fucα1 -4)GlcNAcβ1-3 Galβ1-4Glc |

| LNFP-III | Lacto-N-fucopentaose III | Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3 Galβ1-4Glc |

| LNFP-V | Lacto-N-fucopentaose V | Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-3 Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)Glc |

| LNFP-VI | Lacto-N-fucopentaose VI | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3 Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)Glc |

| LNDFH-I | Lacto-N-difucohexaose I | Fucαl-2Galβ1-3(Fucα1-4)GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc |

| LNDFH-II | Lacto-N-difucohexaose II | Galβ1-3(Fucα1-4)GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)Glc |

Milk

Matched colostrum and milk samples from the same mother (de-identified) were obtained from local Boston hospitals coordinated through the Mothers’ Milk Bank of New England, under approval of the Partners/MGH Institutional Review Board. Milk samples were stored at −20°C until use. Method development was with pooled milk from different stages of lactation. Four matched sets of colostrum and milk were analyzed individually by this procedure to determine biological variation of expression.

Milk oligosaccharide isolation and reduction

Thawed milk (100 L) was centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Avoiding the upper, creamy layer, 50 L of the lower, aqueous layer was pipetted into a clean test tube. EtOH (100 L) was added to each sample to give 66.7% EtOH. After centrifugation for 60 min at 4°C, the precipitate, containing mostly proteins, was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The clear supernatant (50 L), containing essentially all of the oligosaccharides and lactose, was transferred to another test tube and diluted 20-fold with 950 L deionized water.

To reduce the milk oligosaccharides to their alditols, 25 L diluted milk oligosaccharide extract was mixed with 25 L of freshly prepared aqueous 0.5 M NaBH4 and incubated for 30 min at ambient temperature. The reaction was terminated with the addition of 25 L of 0.5 M acetic acid, and 10 L of the resultant solution was injected directly into the LC-MS for quantitative analysis.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

An Agilent high-performance liquid chromatograph 1100 series system coupled to a single-quadrupole Agilent MSD mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ion source (ESI) was controlled by ChemStation A.10.02, including data acquisition and processing. The HPLC stationary phase was a 3-μm hypercarb column (100 × 2.1 mm i.d.; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the mobile phase was CH3CN and H2O run at 25°C. The LC gradient was delivered at 0.20 mL/min and consisted of an initial linear increase from 0% to 12% CH3CN over 21 min, a linear decrease to 0% CH3CN for 1 min, and equilibration at 0% CH3CN for 8 min, allowing a sample injection every 30 minutes.

The operating parameters of the ion source were optimized using 100 μg/mL tuning solutions of 11 oligosaccharides (2′-FL, 3-FL, LNT, LNnT, LNFP-I, LNFP-II, LNFP-III, LNFP-V, LNFP-VI, LNDFH-I, and LNDFH-II) to obtain the best performance from the mass spectrometer. Although the absolute signal was higher in positive ion mode, all 11 oligosaccharides exhibited a better limit of detection of less than 0.001 μg/mL in negative ion mode, perhaps due to effects of molecules in the matrix, including salts from the reduction. In negative ion mode, the most abundant ions for each of the 11 oligosaccharides were their deprotonated ions [M-H]−, and instrumental parameters were tuned to maximize their generation. Typical sets of parameters used in this study were as follows: drying gas flow at 10 L/min, nebulizer pressure at 40 psi, drying gas temperature at 350°C, and capillary voltage at 5,000 V. For the quantification of the 11 oligosaccharides in human milk samples, the MS detector was operated in selected ion monitoring mode at unit mass resolution with dwell time at 55 ms. The deprotonated ions [M-H]− used for mass spectrometric monitoring were m/z 487 for 2′-FL and 3-FL, 706 for LNT and LNnT, 852 LNFP-I, LNFP-II, LNFP-V, and LNFP-VI, and 998 for LNDFH-I and LNDFH-II and m/z 489 for the alditol forms of 2′-FL and 3-FL, 708 for the alditol forms of LNT and LNnT, 854 for the alditol forms of LNFP-I, LNFP-II, LNFP-V, and LNFP-VI, and 1000 for the alditol forms of LNDFH-I and LNDFH-II.

Standard Curves

A stock solution of the 11 oligosaccharide standards at 50 g/mL was serially diluted with deionized MilliQ H2O to 20, 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, 0.313, 0.156, 0.078 and 0.039 g/mL to construct standard curves, and were subjected to the same extraction protocol as was used for human milk sample preparation. Similarly, standards were added to pooled milk samples and the oligosaccharides were then quantified: the known concentration of each oligosaccharide in the pooled milk was subtracted from the total amount measured to give the incremental increase that could be attributed to the added standard, and to create a curve. The peak area (Y) corresponding to each oligosaccharide was regressed against the nominal concentration of the test oligosaccharide (X, g/mL) with weighting of the reciprocal concentration (1/X) to create each standard curve, and its closeness of fit was calculated as the coefficient of determination R2. Weighting with 1/X during regression allows more accurate accounting of low concentration samples.

Method validation

After reduction, the sample was subjected to LC-MS analysis without further sample cleanup. Stability of the 11 oligosaccharides in the resultant solution was evaluated at 0.313 and 10 g/mL at room temperature for 24 h in the autosampler of the LC-MS.

To determine the precision and accuracy of the method, standard mixtures of the 11 test oligosaccharides were analyzed five times at three different nominal concentrations (0.313, 1.25, and 10 g/mL) in water. The measured value was calculated from the standard curve (previously obtained as the regression equation), expressed as the mean of the five values. The accuracy was measured as the difference between the nominal value and measured value expressed as a percentage of the nominal value. The precision was expressed as the CV of the five identical samples at a given concentration of a given standard, i.e., the standard deviation divided by the mean value multiplied by 100.

To measure the efficiency of recovery of the extraction protocol, 125, 500, and 2000 g/mL of 2′-FL, 3-FL, LNT, LNnT, LNFP-I, LNFP-III, LNDFH-I, and 12.5, 50, and 200 g/mL for all others were added to pooled human milk. The spiked human milk samples were diluted 200-fold to evaluate the recovery of 2′-FL, 3-FL, LNT, LNnT, LNFP-I, LNFP-III, LNDFH-I, and 20-fold to evaluate the recovery of other oligosaccharides followed by their analysis by the analytical procedure described above. The incremental increases in the concentrations of the 11 oligosaccharides after their addition to milk (minus those in the original milk), divided by the value of the added standards, multiplied by 100, is the percent recovery at each concentration of each standard. These data also allowed the precision (CV) and linearity (regression and R2) to be calculated in the presence of milk matrix. The experiment was conducted in triplicate (n=3).

Measuring individual variation

Four sets of matched colostrum and milk from four mothers were measured. Each colostrum was collected on day 3 of lactation, and milks from the same donors were from days 14, 14,, and 18 postpartum. Donors 1, 2, and 4 delivered at term (39-42 weeks), while donor 3 delivered at 24 weeks. The results of analyzing these samples address whether the technique developed herein is able to detect natural variation in the amount of oligosaccharides expressed in human milk by different mothers, and within the same mother at different stages of lactation.

Results

Resolution and reduction of oligosaccharides

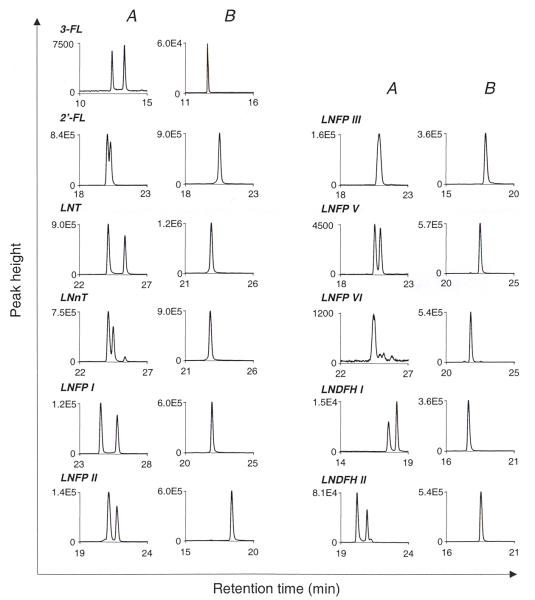

The HPLC with porous graphitic carbon as the stationary phase, and with water and acetonitrile as the mobile phase, as described herein, was able to separate the eleven native milk oligosaccharides tested, which include structural isomers, into distinct peaks, but require long run times. However, this technique also resolved the / anomeric isomers of the oligosaccharides (except LNFP-III and LNFP-VI), resulting in two peaks per oligosaccharide (Fig 1A). This confounded identification and quantification of each oligosaccharide in a native mixture from milk.

Fig.1.

LC/MS of 11 individual neutral standard milk oligosaccharides before (A) and after (B) reduced by NaBH4. The two split peaks of each oligosaccharide merged into one single peak corresponding to the alditol after NaBH4 reduction. Sensitivity of detection of the alditols also increased over that of the aldols for most of the oligosaccharides.

Optimization of oligosaccharide reduction

Sequential aliquots of the reaction mixture were analyzed as oligosaccharides were being reduced into their alditols by NaBH4 reduction [16; 31]; as the reaction progressed, the split peaks of each oligosaccharide disappeared and merged into one single peak in the ion channel whose m/z was 2 Da more than the original (Fig 1B). Moreover, the alditol form of an oligosaccharide produced up to a 500-fold higher response in the mass spectrometer than the combined / anomeric isomers of the aldehyde forms.

The performance of a mass spectrometer can deteriorate if the inorganic salt in the injection solution builds up in the instrument. However, minimal extraction steps allow high-throughput routine analysis of large numbers of samples. To balance these opposing considerations,, reaction conditions were tested for rapid complete reduction with minimum reagent. Reduction of the 11 standards at 20 g/mL oligosaccharides (the highest concentration within the dynamic range of this method) in freshly made 0.25 mol/L of NaBH4 for 0.5 h at room temperature was sufficient to quantitatively reduce the oligosaccharides from milk (data not shown). Accordingly, these reduction conditions were adopted throughout the study.

LC-MS of oligosacchdeari alditols

Next, a mobile phase gradient of water and acetonitrile was devised to provide full quantifiable baseline resolution of the alditols while minimizing chromatographic run time. Fig 2 (left panel) contains LC-MS chromatograms of the mixture of the 11 standards of interest. The 11 peaks were fully resolved by utilizing differences in m/z ratios of the deprotonated negative ions (MS) in conjunction with differences in retention time (HPLC) to resolve isomers of identical molecular weights. The resolution between the detectable peaks in typical colostrum (Fig 2; middle panel) and milk (Fig 2; right panel) samples are comparable to isolated standards.

Fig.2.

LC/MS of the alditols of 11 neutral oligosaccharides from standard solution, colostrum, and milk samples.

Method validation

The 11 alditol products of oligosaccharides, at both low (0.313 g/mL) and high (10 g/mL) concentrations, were stable for 24 h at room temperature in the final solution following reduction. Thus, loading of up to 48 human milk oligosaccharide samples into an unrefrigerated autosampler, or storage at ambient temperature between preparation and analysis of the reduced analyte, should not interfere with accurate quantification.

The dynamic range and linearity for the simultaneous quantification of the 11 oligosaccharides were evaluated through the use of a series of two-fold dilutions as standard curves. As seen in Table 2, the relationship between concentration and response for each of the 11 standards was linear over the 256- to 512-fold range tested (0.156-~20 g/mL for LNDFH-I; 0.078-~20 g/mL for the rest). As expected, the slopes and intercepts of the regression equations were not identical for each of the 11 standards. The lower limit of detection (signal to noise ≤3) was 0.039 g/mL for LNDFH-I and 0.010 g/mL for the remaining oligosaccharides. The excellent linearity for the curve over the entire dynamic range is evident by the coefficient of determination (R2) of over 0.998 for all 11 standards. A series of standards was similarly added to pooled milk samples, and the total response for each oligosaccharide was corrected for the amount of this oligosaccharide known to be in the milk sample; the residual response was due to the added oligosaccharide standard. These values were analyzed by regression, as above, and also displayed a highly linear response (data not shown) similar to that seen in water, above.

Table2.

Linearity of calibration curve for each oligosaccharide.

| Oligosaccharide | Regression equation | Coefficient of Determination (R2) |

Dynamic range (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2′-FL | Y = 49901 X + 942 | 0.998 | 0.078 ~ 20 |

| 3-FL | Y = 27754 X + 1354 | 0.998 | 0.078 ~ 20 |

| LNT | Y = 41748 X + 696 | 0.998 | 0.078 ~ 20 |

| LNnT | Y = 48641 X + 1315 | 0.998 | 0.078 ~ 20 |

| LNFP-I | Y = 12913 X + 428 | 0.998 | 0.078 ~ 20 |

| LNFP-II | Y = 10537 X + 339 | 0.998 | 0.078 ~ 20 |

| LNFP-III | Y = 36283 X − 607 | 0.998 | 0.078 ~ 20 |

| LNFP-V | Y = 24390 X + 424 | 0.998 | 0.078 ~ 20 |

| LNFP-VI | Y = 13768 X + 147 | 0.998 | 0.078 ~ 20 |

| LNDFH-I | Y = 5804 X + 78 | 0.998 | 0.156 ~ 20 |

| LNDFH-II | Y = 11498 X + 119 | 0.998 | 0.07~20 |

Note: Y is peak area; X is nominal standard concentration (μg/mL)

The precision and accuracy of the method were tested at three different concentrations (0.313, 1.25, and 10 g/mL) representing low, intermediate, and high portions of the dynamic range for each standard (Table 3). Each measurement of each standard was repeated in five independent analyses, and the precision was expressed as the CV. The range of CV for all of the concentrations of standards was between 1% and 9%. The accuracy, a comparison between the nominal and measured concentrations, was measured at the same low, intermediate, and high concentrations and ranged between 86% and 104%.

Table 3.

Precision (CV) and accuracy (recovery) of HMOS in water (n = 5).

| HMOS | 0.313 μg/mL |

1.25 μg/mL |

10 μg/mL |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | CV | Rec | Measured | CV | Rec | Measured | CV | Rec | |

| 2′-FL | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 4 | 101 | 1.10 ± 0.04 | 4 | 88 | 8.7 ± 0.4 | 4 | 87 |

| 3-FL | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 4 | 104 | 1.19 ± 0.01 | 1 | 95 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 7 | 90 |

| LNT | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 3 | 99 | 1.18 ± 0.02 | 2 | 94 | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 3 | 96 |

| LNnT | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 3 | 101 | 1.16 ± 0.02 | 2 | 93 | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 3 | 96 |

| LNFP-I | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 5 | 102 | 1.22 ± 0.02 | 1 | 98 | 9.6 + 0.2 | 2 | 96 |

| LNFP-II | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 3 | 94 | 1.13 ± 0.04 | 4 | 90 | 8.5 ± 0.2 | 2 | 85 |

| LNFP-III | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 4 | 98 | 1.16 ± 0.03 | 3 | 93 | 9.8 ± 1.5 | 1 | 98 |

| LNFP-V | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 3 | 100 | 1.21 ± 0.03 | 2 | 97 | 9.7 ± 0.4 | 4 | 97 |

| LNFP-VI | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 3 | 101 | 1.22 ± 0.03 | 2 | 98 | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 4 | 93 |

| LNDFH-I | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 6 | 102 | 1.25 ± 0.03 | 3 | 100 | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 3 | 93 |

| LNDFH-II | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 7 | 97 | 1.12 ± 0.04 | 4 | 90 | 8.6 ± 0.4 | 9 | 86 |

Note: Measured is concentration derived from peak area (μg/mL); CV = SD/Mean × 100%; Rec is accuracy (% of added standard)

Authentic standards were added to aliquots of a pooled milk sample to measure any effects of milk matrix on the response factor (regression curve), oligosaccharide precision, or recovery (accuracy) of the oligosaccharides during extraction from milk. The data in Table 4 indicate that there was little interference by milk components from the matrix (milk) on MS detection after extraction of the oligosaccharides from the milk on linearity (regression curve), accuracy (CV) and recovery (accuracy). Recovery ranged from 96% to 106% indicating that the sample pretreatment quantitatively extracts all of the 11 oligosaccharides measured by the method. The oligosaccharides in pooled human milk samples displayed a CV of less than 15%, for added oligosaccharides. As described earlier, the spiked pooled human milk sample displayed similar regression curves and R2 values for the added authentic standards. . Thus, this technique was tested for its ability to measure oligosaccharides in individual milk samples.

Table 4.

Linearity (R2)*, precision (CV), and accuracy (recovery) of HMOS added to pooled human milk** (n=3).

| HMOS | Poole d milk dilutio n |

Native HMOS in dilute milk μg/mL (CV%) |

Dilute milk spiked at 3 levels with HMOS Native + spiked (CV%, Recovery%***) |

Recovery average (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.625 μg/mL | 2.5 μg/mL | 10 μg/mL | ||||

| 2′-FL | 200 | 4.5 ± 0.3 (6) | 5.1 ± 0.2 (4, 98) | 7.2 ± 0.5 (8, 106) | 13 ± 1 (8, 90) | 98 |

| 3-FL | 200 | 1.5 ± 0.1 (8) | 2.1 ± 0.1 (6, 103) | 4.2 ± 0.2 (6, 109) | 11.1 ± 0.3 (3, 96) | 103 |

| LNT | 200 | 1.8 ± 0.1 (7) | 2.4 ± 0.1 (5, 94) | 4.2 ± 0.4 (9, 98) | 11.5 ± 0.9 (8, 97) | 96 |

| LNnT | 200 | 2.4 ± 0.2 (9) | 3.1 ± 0.1 (3, 110) | 5.1 ± 0.4 (8, 109) | 12.3 ± 0.6 (5, 99) | 106 |

| LNFP-I | 200 | 8.0 ± 0.3 (4) | 8.6 ± 0.8 (9, 98) | 10.7 ± 0.5 (5, 106) | 17.6 ± 1.3 (7, 96) | 100 |

| LNFP-III | 200 | 1.1 ± 0.2 (13) | 1.7 ± 0.1 (5, 99) | 3.7 ± 0.2 (6, 103) | 11.6 ± 0.4 (3, 705) | 102 |

| LNDFH-I | 200 | 3.0 ± 0.2 (6) | 3.7 ± 0.3 (8, 100) | 5.7 ± 0.1 (2, 105) | 13.6 ± 0.8 (5, 706) | 104 |

| LNFP-II | 20 | 4.6 ± 0.2 (3) | 5.2 ± 0.3 (6, 104) | 7.2 ± 0.5 (7, 107) | 15.1 ± 0.2 (1, 105) | 105 |

| LNFP-V | 20 | 0.6 ± 0.1 (11) | 1.3 ± 0.1 (11, 106) | 3.2 ± 0.3 (8, 102) | 10.4 ± 0.6 (5, 98) | 102 |

| LNFP-VI | 20 | 0.3 ± 0.1 (10) | 0.9 ± 0.1 (14, 103) | 2.8 ± 0.1 (4, 101) | 10.0 ± 0.3 (3, 97) | 100 |

| LNDFH-II | 20 | 0.1 ± 0.1 (9) | 0.8 ± 0.1 (9, 102) | 2.7 ± 0.3 (10, 104) | 9.8 ± 0.9 (9, 97) | 101 |

Note:

R2 values given in text

Pooled milk from 13 donors;

Recovery%=(Conc. in dilute pooled milk with spiked oligosaccharides - Conc. in dilute pooled milk)/Conc. of spiked oligosaccharides ×100

Ability to discern natural variation of human milk oligosaccharides

From four mothers, colostrum (3 d postpartum) and matched more mature (14-29 d) milk samples were analyzed. This tests the ability of the technique to discern differences in expression of neutral oligosaccharides among individuals and changes during the course of lactation. Most oligosaccharides were consistently detected in all samples (Table 5). Noteworthy is the remarkable variation in concentrations of milk oligosaccharides among different mothers, with two different expression patterns apparent in these four donors. For donors 1, 2, and 3, the amounts of 2′-FL, LNFP-I, and LNDFH-I were present in the highest concentration for both colostrum and milk samples, followed by LNT, LNnT, LNFP-III, 3-FL, with the remaining oligosaccharides present in relatively low concentrations. LNDFH-II was not detected. In contrast, the milk (colostrum) of donor 4 at day 3 contained much lower concentrations of oligosaccharides than any of the other samples, but by day 29 the values seemed to approach those of the other samples. The significance of differing patterns of oligosaccharides in individual milk samples has been discussed in earlier publications [12].

Table 5.

Concentrations of neutral oligosaccharides from five donors (μg/mL).

| HMOS | Donor 1 |

Donor 2 |

Donor 3 |

Donor 4 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d 3 | d 14 | d 3 | d 16 | d 3 | d 18 | d 3 | d 29 | |

| 2′-FL | 1218 | 1074 | 1356 | 1140 | 1200 | 1071 | 696 | 1029 |

| 3-FL | 111 | 189 | 147 | 315 | 240 | 225 | 27 | 198 |

| LNT | 264 | 153 | 498 | 327 | 192 | 105 | 87 | 192 |

| LNnT | 354 | 546 | 213 | 633 | 195 | 651 | 162 | 687 |

| LNFP-I | 1797 | 1545 | 1551 | 1542 | 1492 | 1635 | 840 | 1473 |

| LNFP-II | 60 | 93 | 60 | 207 | 30 | 159 | 18 | 132 |

| LNFP-III | 255 | 201 | 165 | 156 | 210 | 132 | 63 | 186 |

| LNFP-V | 6 | 12 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 15 |

| LNFP-VI | 9 | 6 | 27 | 15 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 9 |

| LNDFH-I | 726 | 540 | 1032 | 1215 | 720 | 849 | 147 | 603 |

| LNDFH-II | nd | 12 | nd | 18 | nd | 24 | 3 | 9 |

| Total | 4800 | 4371 | 5051 | 5583 | 4287 | 4872 | 2045 | 4533 |

Note: d, days after delivery; nd, not detected

The concentrations of neutral oligosaccharides decreased between colostrum (3 d) and the more mature milk of each mother in the milk of the mother delivering early (donor 3) and the mothers who delivered at term (donors 1 and 2). In contrast, donor 4, who delivered at term, had her milk oligosaccharide levels increase as lactation progressed. The ability to measure these differences unambiguously in this trial set of samples strongly suggests that this LC-MS analytical technique could be used successfully to discern these individual differences in larger cohorts, and to define their biological correlates.

Discussion

The separation of native HMOS has always been a challenge: Oligosaccharides are polar compounds that are not well resolved by traditional reversed-phase modified silica columns. HMOS contain many structural isomers that are difficult to resolve to baseline by chromatography. Oligosaccharides do not have strong intrinsic chromophores, which results in poor specificity and low sensitivity by optical absorbance. Thus, the published HPLC methods all have limitations. Martin-Sosa and coworkers used an NH2 column to resolve 7 native human milk oligosaccharides with UV detection at 206 nm [18]. Although their sample preparation is simple, a 60-min run is required, baseline resolution is not achieved for all analytes, and the sensitivity is limited. Several research groups employed high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with electrochemical detection for human milk oligosaccharide analysis [17; 19; 21]. Again, a long run time does not fully resolve the major oligosaccharides to baseline, such as 3-FL and LNDFH-I, LNFP-II and LNFP-III [21], and the sensitivity was in the range of 50 to 100 g/mL. Another common approach is precolumn derivatization of HMOS with chromophores or fluorophores via reductive amination. The reducing end of HMOS reacts with the amino group of the tag reagent, resolution is by normal- or reverse-HPLC, and detection is by measuring absorption or fluorescence of the tag moieties [13; 16; 20]. This improves sensitivity of optical detection to the level of electrochemical detection. But some isomers, for example, isomers of LNT and LNnT and of LNFP-II and LNFP-III [13] still co-elute despite the improved chromatographic behavior conferred by tagging. Another type of derivatization that had been favored by our laboratory is the perbenzoylation of all accessible hydroxy groups, which improves the chromatographic resolution and sensitivity of UV detection, and has proved useful in defining biological functions of HMOS. However, derivatization and clean-up requires rigorous reaction conditions, is tedious, time-consuming, and can introduce significant variation to the analysis.

Carbon columns have been extensively used to isolate carbohydrates due to their retention of polar compounds and strong separation power. From the 1990s, graphitic carbon columns for HPLC have proved useful for structural identification of glycans and in gIycomics [31-33]. However, the high resolution of porous graphitic carbon as the stationary phase of HPLC separates anomeric oligosaccharides from their anomeric isomers. The complexity of the oligosaccharide mixtures of biologic origin, and especially of human milk oligosaccharides, makes it necessary to reduce oligosaccharides prior to analysis to allow for a single peak for each alditol. Most reduction procedures use excess reagent with a subsequent clean-up step [16; 31]. To eliminate the necessity of clean-up prior to injection of the sample into the LC-MS, reaction conditions were devised that allowed for complete reduction with more limited reagent concentrations. HMOS could be transformed completely by incubating in 0.25 mol/L NaBH4 for 30 min with consistent yields, and the resulting solution was injected directly onto the HPLC column to increase the throughput of the technique. The graphitic carbon column was able to translate the chemical and physical differences of the reduced HMOS alditol structural isomers into baseline resolved chromatographic peaks. It was not necessary to resolve all of the oligosaccharide alditols, as those of different molecular weight that co-eluted (LNFP-III and LNDH-I, and LNFP-II and LNDFH-II) could be measured independently by specific ion monitoring by the MS. This allowed the 11 reduced oligosaccharides to be baseline separated either by retention time or by molecular weight within a 30-min run. Moreover, MS is a very sensitive detector, and the lower limit of quantification of our method, 0.039 g/mL, is 2- to 3-orders of magnitude more sensitive than other human milk oligosaccharide instrumental analysis methods in the literature [14,17,21]. Moreover, our sensitivity for milk oligosaccharides is equivalent to the highly sensitive 2-aminoacridone (AMAC) ion-laser fluorescence method developed for analysis of the heparin sulfate disaccharides [46; 47]. Note that the LC-MS technique described herein does not require the derivatization and clean-up steps of fluorescence, but only a simple reduction. Furthermore, the LC-MS sensitivity might be further increased by using a tandem MS-MS as the detector. Notwithstanding, the sensitivity, precision, and linearity combined with high throughput make this a method of choice for defining HMOS in terms of individual variation, changes over the course of lactation, and in defining their biologic role in protection of infants from diseases.

Table 6 compares values reported by Asakuma et al. [13], Musumeci et al. [19], Thurl et al. [21], Kunz et al. [17] and our previous method of Chaturvedi et al. [16]. The range of concentrations of the 11 oligosaccharides in human milk measured by our LC-MS method encompassed most of the concentrations reported in prior publications using these other methods.

Table 6.

Concentrations of oligosaccharides reported in other studies (mg/mL).

| Reference | Asakuma et al. | Musumeci et al. | Thurl et al. | Kunz et al. | Chaturvedi et al. | Current data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactation day | 3 | 3 | na | na | 30-60 | 3-29 |

| 2′-FL | 0.38-2.76 | 0.2-3.4 | 1.8 | nr | 1.2 | 0.006-1.36 |

| 3-FL | 0.01-0.38 | nr | 0.5 | nr | 0.4 | 0.03-1.34 |

| LNT | 0.41-3.01 | nr | 0.9 | 0.50-1.50 | 0.4 | 0.16-1.18 |

| LNnT | 0.3-0.75 | nr | 0.1 | nr | 0.2 | 0.04-0.50 |

| LNFP-I | 0.38-3.94 | 0.3-2.8 | 0.7 | 1.0-1.50 | 0.9 | 0.001-1.80 |

| LNFP-II | 0.13-1.32 | nr | 0.5 | 0.50-1.0 | 0.6 | 0.02-1.79 |

| LNFP-III | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | 0.06-0.78 |

| LNDFH-I | 0.78-2.98 | nr | 0.6 | nr | 0.6 | nd-1.22 |

| LNDFH-II | 0.003-0.1 | nr | 0.2 | nr | 0.1 | nd-0.22 |

Note: na, not available; nr, not reported; nd, not detected

These data indicate that populations of lactating mothers exhibit individual variation in their expression of oligosaccharides and changes over the course of lactation. The present LC-MS method can measure differences in these 11 milk oligosaccharides with an unprecedented degree of sensitivity, precision, and accuracy. The relatively straightforward sample preparation and the throughput of this technique are sufficient to allow this variation to be fully studied and documented in future studies of larger human cohorts. These may allow the biological significance of the variation in oligosaccharide expression in milk to be studied in relation to specific disease risks and medical outcomes in nursing infants.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by NIH grant HD013021 and AI075563. Author disclosure: Yuanwu Bao and Ceng Chen have no conflict of interest; David Newburg owns shares of Glycosyn, Inc., and all potential conflicts of interest have been disclosed to the NIH and are being managed by Boston College.

Abbreviations used:

- m/z

mass to charge ratio

- HMOS

human milk oligosaccharides

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- CE

capillary electrophoresis

- MS-MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- Glc

D-glucose

- Gal

D-galactose

- GlcNAc

N-acetylglucosamine

- Fuc

L-fucose

- Neu5Ac

NANA, sialic acid N-acetyl neuraminic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations for the milk oligosaccharides are listed in Table 1.

References

- [1].Newburg DS, Neubauer SH. Carbohydrates in milk: analysis, quantitites, and significance. In: Jensen RG, editor. Handbook of Milk Composition. Academic Press; Orlando: 1995. pp. 273–349. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kunz C, Rudloff S, Baier W, Klein N, Strobel S. Oligosaccharides in human milk: structural, functional, and metabolic aspects. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2000;20:699–722. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Newburg DS, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Morrow AL. Human milk glycans protect infants against enteric pathogens. Ann. Rev. Nutr. 2005;25:37–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stahl B, Thurl S, Zeng J, Karas M, Hillenkamp F, Steup M, Sawatzki G. Oligosaccharides from human milk as revealed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Analytical Biochemistry. 1994;223:218–226. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Newburg DS. Oligosaccharides in human milk and bacterial colonization. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2000;30(Suppl 2):S8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Stepans MB, Wilhelm SL, Hertzog M, Rodehorst TK, Blaney S, Clemens B, Polak JJ, Newburg DS. Early consumption of human milk oligosaccharides is inversely related to subsequent risk of respiratory and enteric disease in infants. Breastfeeding Med. 2006;1:207–15. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2006.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gyorgy P, Norris RF, Rose CS. Bifidus factor. I. A variant of Lactobacillus bifidus requiring a special growth factor. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1954;48:193–201. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(54)90323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].LoCascio RG, Ninonuevo MR, Freeman SL, Sela DA, Grimm R, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA, German JB. Glycoprofiling of bifidobacterial consumption of human milk oligosaccharides demonstrates strain specific, preferential consumption of small chain glycans secreted in early human lactation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:8914–9. doi: 10.1021/jf0710480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sharon N. Carbohydrate-lectin interactions in infectious disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1996;408:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Angeloni S, Ridet JL, Kusy N, Gao H, Crevoisier F, Guinchard S, Kochhar S, Sigrist H, Sprenger N. Glycoprofiling with micro-arrays of glycoconjugates and lectins. Glycobiology. 2005;15:31–41. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Morrow AL, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Altaye M, Jiang X, Guerrero ML, Meinzen-Derr JK, Farkas T, Chaturvedi P, Pickering LK, Newburg DS. Human milk oligosaccharides are associated with protection against diarrhea in breast-fed infants. J. Pediatr. 2004;145:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Newburg DS, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Altaye M, Chaturvedi P, Meinzen-Derr J, Guerrero ML, Morrow AL. Innate protection conferred by fucosylated oligosaccharides of human milk against diarrhea in breastfed infants. Glycobiology. 2004;14:253–63. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Asakuma S, Urashima T, Akahori M, Obayashi H, Nakamura T, Kimura K, Watanabe Y, Arai I, Sanai Y. Variation of major neutral oligosaccharides levels in human colostrum. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;62:488–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cardon P, Parente JP, Leroy Y, Montreuil J, Fournet B. Separation of sialyl-oligosaccharides by high-performance liquid chromatography. Application to the analysis of mono-, di-, tri- and tetrasialyl-oligosaccharides obtained by hydrazinolysis of alpha 1-acid glycoprotein. J. Chromatogr. 1986;356:135–46. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)91473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Charlwood J, Tolson D, Dwek M, Camilleri P. A detailed analysis of neutral and acidic carbohydrates in human milk. Anal. Biochem. 1999;273:261–77. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chaturvedi P, Warren CD, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Pickering LK, Newburg DS. Milk oligosaccharide profiles by reversed-phase HPLC of their perbenzoylated derivatives. Anal. Biochem. 1997;251:89–97. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kunz C, Rudloff S, Hintelmann A, Pohlentz G, Egge H. High-pH anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection and molar response factors of human milk oligosaccharides. J. Chromatogr. B. 1996;685:211–221. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Martin-Sosa S, Martin MJ, Garcia-Pardo LA, Hueso P. Sialyloligosaccharides in human and bovine milk and in infant formulas: variations with the progression of lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2003;86:52–9. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73583-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Musumeci M, Simpore J, D’Agata A, Sotgiu S, Musumeci S. Oligosaccharides in colostrum of Italian and Burkinabe women. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2006;43:372–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000228125.70971.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sumiyoshi W, Urashima T, Nakamura T, Arai I, Saito T, Tsumura N, Wang B, Brand-Miller J, Watanabe Y, Kimura K. Determination of each neutral oligosaccharide in the milk of Japanese women during the course of lactation. Br. J. Nutr. 2003;89:61–9. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Thurl S, Muller-Werner B, Sawatzki G. Quantification of individual oligosaccharide compounds from human milk using high-pH anion-exchange chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1996;235:202–206. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Townsend RR, Hardy MR, Cumming DA, Carver JP, Bendiak B. Separation of branched sialylated oligosaccharides using high-pH anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection. Anal. Biochem. 1989;182:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90708-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Townsend RR, Hardy MR, Hindsgaul O, Lee YC. High-performance anion-exchange chromatography of oligosaccharides using pellicular resins and pulsed amperometric detection. Anal. Biochem. 1988;174:459–70. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Watson E, Bhide A, Kenney WC, Lin FK. High-performance anion-exchange chromatography of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Anal. Biochem. 1992;205:90–5. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90583-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bao Y, Newburg DS. Capillary electrophoresis of acidic oligosaccharides from human milk. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:2508–15. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shen Z, Warren CD, Newburg DS. High-performance capillary electrophoresis of sialylated oligosaccharides of human milk. Anal. Biochem. 2000;279:37–45. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shen Z, Warren CD, Newburg DS. Resolution of structural isomers of sialylated oligosaccharides by capillary electrophoresis. J. Chromatogr. A. 2001;921:315–321. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)00872-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Song JF, Weng MQ, Wu SM, Xia QC. Analysis of neutral saccharides in human milk derivatized with 2-aminoacridone by capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detection. Anal. Biochem. 2002;304:126–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Karlsson A, Karlsson O. Enantiomeric separation of amino alcohols using Z-L-Glu-L-Pro or Z-L-Glu-D-Pro as chiral counter ions and hypercarb as the solid phase. Chirality. 1997;9:650–655. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Barroso B, Dijkstra R, Geerts M, Lagerwerf F, van Veelen P, de Ru A. On-line high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometric characterization of native oligosaccharides from glycoproteins. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2002;16:1320–9. doi: 10.1002/rcm.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ninonuevo MR, Park Y, Yin H, Zhang J, Ward RE, Clowers BH, German JB, Freeman SL, Killeen K, Grimm R, Lebrilla CB. A strategy for annotating the human milk glycome. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:7471–80. doi: 10.1021/jf0615810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pabst M, Bondili JS, Stadlmann J, Mach L, Altmann F. Mass + retention time = structure: a strategy for the analysis of N-glycans by carbon LC-ESI-MS and its application to fibrin N-glycans. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:5051–7. doi: 10.1021/ac070363i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Robinson S, Bergstrom E, Seymour M, Thomas-Oates J. Screening of underivatized oligosaccharides extracted from the stems of Triticum aestivum using porous graphitized carbon liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:2437–45. doi: 10.1021/ac0616714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chin ET, Papac DI. The use of a porous graphitic carbon column for desalting hydrophilic peptides prior to matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 1999;273:179–85. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Xing J, Apedo A, Tymiak A, Zhao N. Liquid chromatographic analysis of nucleosides and their mono-, di- and triphosphates using porous graphitic carbon stationary phase coupled with electrospray mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:1599–606. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Helali N, Monser L. Stability indicating method for famotidine in pharmaceuticals using porous graphitic carbon column. J. Sep. Sci. 2008;31:276–82. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200700347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hsieh Y, Duncan CJ, Brisson JM. Porous graphitic carbon chromatography/tandem mass spectrometric determination of cytarabine in mouse plasma. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:629–34. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Liem LK, Choong LH, Woo KT. Porous graphitic carbon shows promise for the rapid screening partial DPD deficiency in lymphocyte dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase in Chinese, Indian and Malay in Singapore by using semi-automated HPLC-radioassay. Clin. Biochem. 2002;35:181–7. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(02)00303-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Van Den Hauwe O, Perez JC, Claereboudt J, Van Peteghem C. Simultaneous determination of betamethasone and dexamethasone residues in bovine liver by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:857–61. doi: 10.1002/rcm.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Vial J, Hennion MC, Fernandez-Alba A, Aguera A. Use of porous graphitic carbon coupled with mass detection for the analysis of polar phenolic compounds by liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 2001;937:21–9. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)01309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Borisov OV, Field M, Ling VT, Harris RJ. Characterization of oligosaccharides in recombinant tissue plasminogen activator produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells: two decades of analytical technology development. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:9744–9754. doi: 10.1021/ac901498k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Dreyfuss JM, Jacobs C, Gindin Y, Benson G, Staples GO, Zaia J. Targeted analysis of glycomics liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry data. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010;399:727–735. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4235-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Huang R, Pomin VH, Sharp JS. LC-MS(n) analysis of isomeric chondroitin sulfate oligosaccharides using a chemical derivatizaton strategy. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1577–1587. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0174-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Naimy H, Leymarie N, Zaia J. Screening for anticoagulant heparan sulfate octasaccharides and fine structure characterization using tandem mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3743–3752. doi: 10.1021/bi100135d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wei W, Ninonuevo MR, Sharma A, Danan-Leon LM, Leary JA. A comprehensive compositional analysis of heparin/heparan sulfate-derived disaccharide from human serum. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:3703–3708. doi: 10.1021/ac2001077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Militsopoulou M, Lamari FN, Hjerpe A, Karamanos NK. Determination of twelve heparin- and heparan sulfate-derived disaccharides as 2-aminoacridone derivatives by capillary zone electrophoresis using ultraviolet and laser-induced fluorescence detection. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:1104–9. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200204)23:7/8<1104::AID-ELPS1104>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Militsopoulou M, Lecomte C, Bayle C, Couderc F, Karamanos NK. Laser-induced fluorescence as a powerful detection tool for capillary electrophoretic analysis of heparin/heparan sulfate disaccharides. Biomed Chromatogr. 2003;17:39–41. doi: 10.1002/bmc.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]