Abstract

Cardamonin, as shown by the increasing number of publications, has received growing attention from the scientific community due to the expectations toward its benefits to human health. In this study, research on cardamonin is reviewed, including its natural sources, health promoting aspects, and analytical methods for its determination. Therefore, this article hopes to aid current and future researchers on the search for reliable answers concerning cardamonin's value in medicine.

Key Words: : 2′,4′-dihydroxy-6′-methoxy-chalcone; Alpinia; InChIKey=NYSZJNUIVUBQMM-BQYQJAHWSA-N; medicinal chemistry; Zingiberaceae

Introduction

In the last decades, a lot of efforts have been dedicated to research on chalcones. This group of aromatic enones (1,3-diphenyl-2-propenone core structure) belongs to the flavonoid family and is often responsible for the yellow pigmentation of plants.1–3 In fact, the name chalcones comes from the classic Greek word chalkos, “χαλκóς,” which means copper/bronze. However, and of course, the scientific community's interest is beyond a matter of color and mostly aims at the promising cancer chemopreventive properties as well as other remarkable bioactive characteristics like the antioxidant and antibacterial potential.4 Moreover, they have the inherent advantage of occurring naturally, often in plants already present in our diet,5 thus simplifying the process of having these compounds approved within developed pharmaceutical formulations.

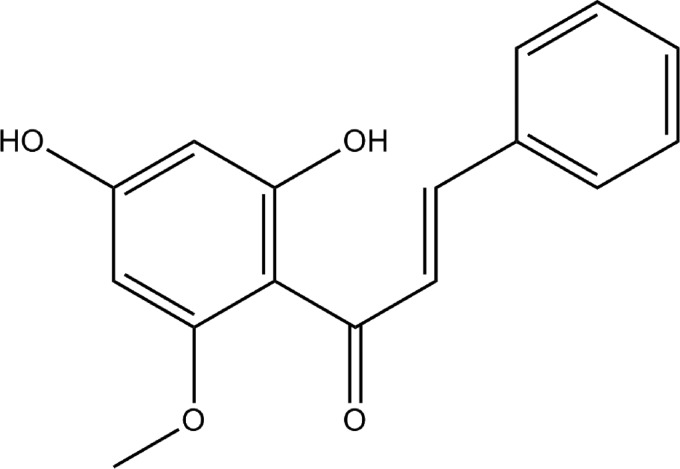

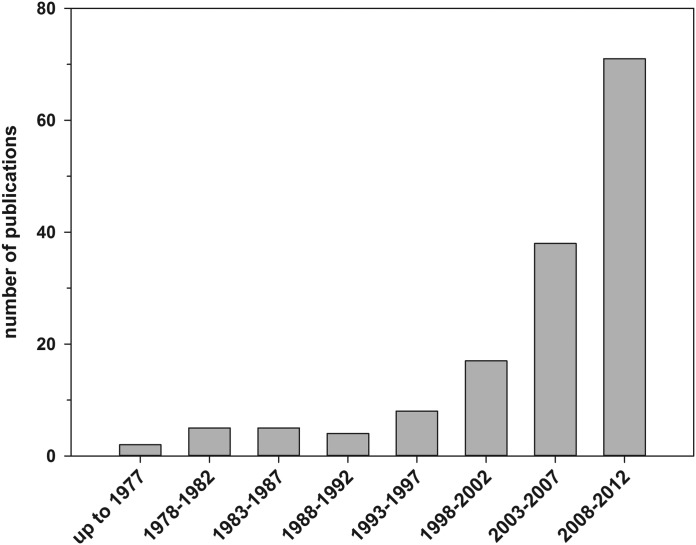

Several chalcones have been subject of interest in medicinal chemistry4 like hesperidin methyl-chalcone (already tested in clinical trials),6 xanthohumol,7–10 licochalcone A,11 flavokawin,12 and xanthoangelol.13 In the authors' opinion, cardamonin (Fig. 1) can be included in this list as can be seen by the increasing number of publications (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Cardamonin structure.

FIG. 2.

Number of published documents per period of time. Source: SciFinder search engine, all publications concerning cardamonin, that is, CAS registry number 1939-14-9.

This article attempts to overview all the work published so far considering the health promoting properties of cardamonin, all plant sources, and finally, a list of all analytical methodologies that have been developed.

Sources Of Cardamonin

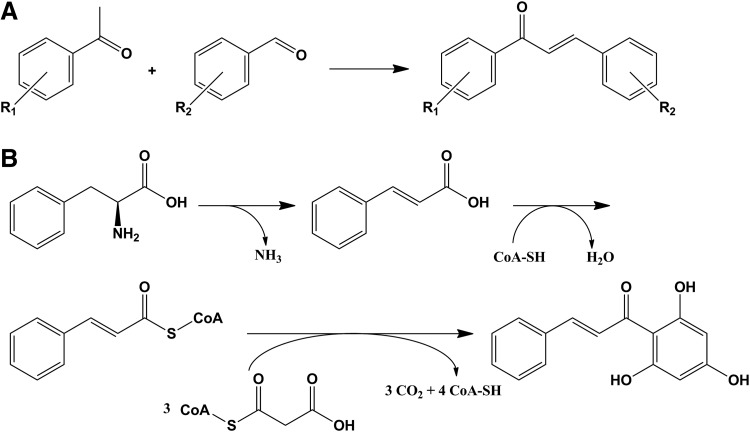

Although chalcones were first synthetized in the laboratory in the end of the XIX century,3 it is still a topic of research nowadays. In general, they are synthetized by acid or base catalyzed Claisen-Schmidt condensation (Fig. 3A) of an aldehyde and a ketone followed by dehydration.2,14–16 There are also articles based on the Suzuki reaction17,18 and an interesting example of chalcone synthesis (including cardamonin) that can be found in literature using a bromomagnesium salt.19

FIG. 3.

General scheme for chalcone synthesis: (A) chemical synthesis, (B) simplified biosynthesis of hydroxylated chalcone.

Of course, naturally occurring synthesis is chemically more complex and involves several enzymes.3,20 The initial product is phenylalanine transformed to cinnamic acid by phenyl ammonium-lyase (EC 4.3.1.24), and then, in several steps where malonyl-CoA plays a major role, a hydroxylated chalcone is obtained (Fig. 3B); quite commonly, the chalcone can be transformed into the corresponding flavanone by a chalcone isomerase.21

The first isolation of naturally occurring chalcones was done in 1910.3 Chalcones are mainly found in the petal pigments, but have been found as well in the heartwood, bark, leaf, fruit, and root of many plant species.3

Cardamonin's name comes from the fact that it can be found in cardamom spice (Fig. 4), but since the first article where it was described,22 it has been found in many other (some of them edible) plant species, such as Alpinia blepharocalyx,23,24 Alpinia gagnepainii,25 Alpinia conchigera,26,27 Alpinia hainanensis,28–40 Alpinia malaccensis,41 Alpinia mutica,42,43 Alpinia pricei,44 Alpinia rafflesiana,45–48 Alpinia speciosa,22,49,50 Amomum subulatum,51 Artemisia absinthium,52 Boesenbergia pandurata,53–60 Boesenbergia rotunda,61,62 Carya cathayensis,63 Cedrelopsis grevei,64 Combretum apiculatum,65 Comptonia peregrina,66 Desmos cochinchinensis,67 Elettaria cardamomum,68 Helichrysum forskahlii,69 Kaempferia parviflora,54 Morella pensylvanica,66 Piper dilatatum,70 Piper hispidum,71 Polygonum ferrugineum,72 Polygonum lapathifolium,73 Polygonum persicaria,74,75 Populus fremontii,76 Populus×euramericana, a hybrid between Populus deltoides and Populus nigra,77 Syzygium samarangense,78 Vitex leptobotrys,79 and Woodsia scopulina.80

FIG. 4.

Photograph of green cardamom seeds by Luc Viatour (www.lucnix.be). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jmf

Table 1 shows the taxonomic position of all species by the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS; www.itis.gov/, http://eol.org/). Some data immediately strike out like the fact that not only cardamonin can be found in many different species, but also they are taxonomically very much apart from each other. Curiously, they are also naturally very distant from each other, geographically speaking. This might be explained by the fact that chalcone isomerases have been found in bacteria,21 thus cardamonin could be the result of an uptake of a previously produced compound, or precursor, in the plant's rhizosphere by the actinomycetes present there. Nevertheless, and not surprisingly, since it includes cardamom spice, the Zingiberaceae family is the most represented.

Table 1.

Sources of Cardamonin Organized Taxonomically

| Kingdom | Division | Class | Order | Family | Genus | Species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plantae | Magnoliophyta | Liliopsida | Zingiberales | Zingiberaceae | Alpinia | Alpinia blepharocalyx | 23, 24 |

| Alpinia conchigera | 26, 27 | ||||||

| Alpinia gagnepainii | 25 | ||||||

| Alpinia hainanensis | 28–40 | ||||||

| Alpinia malaccensis | 41 | ||||||

| Alpinia mutica | 42, 43 | ||||||

| Alpinia rafflesiana | 45–48 | ||||||

| Alpinia speciosa | 22, 49, 50 | ||||||

| Amomum | Amomum subulatum | 51 | |||||

| Boesenbergia | Boesenbergia pandurata | 53–60 | |||||

| Boesenbergia rotunda | 61, 62 | ||||||

| Elettaria | Elettaria cardamomum | 68 | |||||

| Kaempferia | Kaempferia parviflora | 54 | |||||

| Magnoliopsida | Asterales | Asteraceae | Artemisia | Artemisia absinthium | 52 | ||

| Helichrysum | Helichrysum forskahlii | 69 | |||||

| Juglandales | Juglandaceae | Carya | Carya cathayensis | 63 | |||

| Lamiales | Verbenaceae | Vitex | Vitex leptobotrys | 79 | |||

| Magnoliales | Annonaceae | Desmos | Desmos cochinchinensis | 67 | |||

| Myricales | Myricaceae | Comptonia | Comptonia peregrina | 66 | |||

| Morella | Morella pensylvanica | 66 | |||||

| Myrtales | Combretaceae | Combretum | Combretum apiculatum | 65 | |||

| Myrtaceae | Syzygium | Syzygium samarangense | 78 | ||||

| Piperales | Piperaceae | Piper | Piper dilatatum | 70 | |||

| Piper hispidum | 71 | ||||||

| Polygonales | Polygonaceae | Polygonum | Polygonum ferrugineum | 72 | |||

| Polygonum lapathifolium | 73 | ||||||

| Polygonum persicaria | 74, 75 | ||||||

| Salicales | Salicaceae | Populus | Populus fremontii | 76 | |||

| Populus x euramericana | 77 | ||||||

| Sapindales | Rutaceae | Cedrelopsis | Cedrelopsis grevei | 64 | |||

| Pteridophyta | Filicopsida | Polypodiales | Dryopteridaceae | Woodsia | Woodsia scopulina | 80 |

Health Applications

Anti-inflammatory, antineoplastic, and antioxidant activity

Several authors26,36,46,52,81 have aimed to explain the anti-inflammatory activity of cardamonin by fully observing its influence over the signaling pathway of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)—a protein complex that controls transcription of DNA and plays a crucial role in regulating immune responses to infection1,82—and detail the mechanism of action on the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory gene expression. A 27% inhibition of LPS-induced NO production with a 1 μM can be found in literature.83 Its interference over the NF-κB pathway and subsequently, the p65NF-κB protein cellular distribution inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase.47 It also appears to end up inhibiting prostaglandin E2, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) release, thromboxane B2 production, and intracellular reactive oxygen species generation, all in a dose-dependent manner.48,54 In most of these studies, RAW264.7 cells were used and analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, western blotting, and interestingly, luciferase gene reporter assays.84

Wei et al.37 studied the protective effect of cardamonin from acute lung injury in sepsis. Sepsis is a generalized inflammatory response that can be lethal by organ failure; one of the organs commonly affected are the lungs resulting in hypoxemia and pulmonary edema. Studies were carried out in mice, and results showed that cardamonin decreases systemic inflammatory responses, during sepsis, by downregulating TNF-α and interleukins (in this case, IL-1β and IL-6).

Dong et al.23 showed that cardamonin can inhibit arachidonic acid-induced platelet aggregation in human whole blood; authors used indomethacin as a positive control. Similar positive results were obtained by Jantan et al.42 (IC50=73 μM), acetylsalicylic acid was used as a positive control instead (IC50=27 μM) for an arachidonic acid concentration of 500 μM. Acetylsalicylic acid was also used as a positive control in a different study58; in such study, a 4.6% inhibition on carrageenan-induced hind paw edema (with acetylsalicylic acid, a 52.9% inhibition was obtained) with 300 mg/kg given orally. Cardamonin's effect over the platelet activating factor receptor binding was tested and a 42% inhibition value (cedrol, the positive control, in the same conditions gave a 74% value)43; experiments were carried out with rabbit platelets.

It is now known that the unregulated NF-κB pathway plays a key role in neoplastic processes. Not surprisingly, several studies showing cardamonin's antimutagenic activity have also been published. Qin et al.85 showed that cardamonin has a potent activity against multiple myeloma; studies were performed on human multiple myeloma cell lines (RPMI 8226, U266, and ARH-77) and results clearly indicated an antimyeloma activity by inhibiting the growth and proliferation of the mentioned cell lines. Cardamonin also appears to have an enhancement effect on the TRAIL-induced apoptosis, a promising target for selective cancer therapy.49,86 Cardamonin was tested in several cancer cell lines, namely, HuCCA-1—human cholangiocarcinoma cancer cells, HepG2—human hepatocellular liver carcinoma cell line, A549—human lung carcinoma cell line, and MOLT-3—T-lymphoblast (acute lymphoblastic leukemia) cell line.67

Lin et al.44 tested some chalcones effects, including cardamonin, upon cell death of human squamous carcinoma KB cells. With solutions of 74 μM, a viability of ca. 50% was obtained for periods of 24, 48, and 72 h. Cardamonin has shown a preferential cytotoxicity (PC100) against human pancreatic PANC-1 cancer cells in a nutrient-deprived medium superior to 256 μM.59 In this study, where arctigenin was used as a positive control, with other compounds extracted from Boesenbergia pandurata, including a chalcone, lower PC100 values were obtained.

Trakoontivakorn et al.55 extracted cardamonin from finger-root and tested its antimutagenic activity against heterocyclic amines. They obtained a result of 6% inhibition of the N-hydroxylation of 3-amino-1-methyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole, with methanol being the control. Morikawa et al.62 obtained with a 30 μM, a 37% inhibition on the aminopeptidase N activity (a metalloprotease that plays an important role in tumor cell invasion, extracellular and tumor metastasis), curcumin being the reference compound.

Results obtained in trials with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) also point to cardamonin as an effective inhibitor of tumor promoter.56 EBV, is a virus from the Herpesviridae family also named as human herpes virus 4 (HHV-4), which is widely known for causing infectious mononucleosis; however, it is now recognized that it is also implicated in the promotion of several types of neoplastic processes such as Hodgkin's lymphoma. An interesting IC50 of 3.1 μM in studies on the inhibition of EBV activation, whereas an IC50 of 1.5 μM was obtained for acetoxychavicol acetate considered by the authors as a “highly potent EBV activation inhibitor.”

Cardamonin showed potent antioxidant activity in an oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay.67 However, Li et al.87 did not find any relevant antioxidant activity in DPPH and superoxide anion assays at least in the concentrations they tested (as low as 1 μM). Simirgiotis et al.78 extracted cardamonin from wax jambu fruits and carried on experiments concluding that it had a fifth of the IC50 of gallic acid antioxidant activity in DPPH assays and 70% of the cytotoxic activity of epigallocatechin gallate in assays with SW-480 human colon cancer cell lines. Li et al.87 also found relevant cytotoxic activities in hepatoma cells HepG2 cells (IC50=31 μM) being, however, also cytotoxic with normal liver L-02 cells (IC50=23 μM). A larger result for HepG2 cells can also be found in literature (IC50>100 μM) in the same trials, where an IC50 of 46 μM was obtained for Helacyton gartleri.63 Aderogba et al.65 evaluated cardamonin's toxicity using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay on Vero African green monkey kidney cells, it actually had a lower LC50 (7.3 μM) than the positive control berberine (37 μM). A 10% to 20% antioxidant activity was also found with a 50 μM concentration using vitamin C as the positive control.88

Vasorelaxant activity

Fusi et al.89 showed that cardamonin can be vasodilator by inhibiting the entry of calcium to the cell by the voltage-dependent Cav2.1 channel and stimulating the exit of potassium by the calcium-activated KCa1.1 channel. Studies were performed in rat tail artery miocytes. Wang et al.40 concluded that cardamonin can be a vasorelaxant, trials were done on rat isolated main superior mesenteric arteries. An IC50 of 9 μM was obtained with the artery preconstricted with phenylephrine. Huang et al.24 also made studies in the main branch of the superior mesenteric artery, they also concluded that cardamonin induced both endothelium-independent and -dependent relaxation.

Hypoglycemic activity

Yamamoto et al.34 recently showed that cardamonin promotes the uptake of glucose by glucose transporter-4 (GLUT4), an insulin-sensible mediator of glucose from the cytosol to the plasma membrane in muscle cells and adipocytes, usually postprandially active by insulin. Efficient control of GLUT4 is very relevant to the treatment of diabetes mellitus type 2. Studies were performed in L6 myotubes and results showed that a 30 μM cardamonin solution could stimulate GLUT4 for about 1 to 4 h in similar levels to a 0.10 μM insulin solution. Previously, Liao et al.35 had already shown that cardamonin could inhibit the proliferation of insulin-resistant cells. Studies were performed on rats previously induced to be insulin resistant by a 12-week diet rich in fructose.

Anti-infectious activity

Cardamonin, extracted from Piper hispidum, showed to be cytotoxic toward amastigotes of Leishmania amazonensis. The concentration inhibiting 50% of the parasite growth (IC50) was calculated to be 8 μM, while with the reference amphotericin B, IC50 was 0.2 μM. However, the fact that it did show some mild toxicity against peritoneal macrophages71 may complicate the development of pharmaceuticals against leishmaniasis (a still worrying disease caused by parasites from the genus Leishmania).

In addition, quite recently, López et al.72 found cardamonin in a Polygonum, and the studies performed lead them to conclude that cardamonin has antifungal activity toward Epidermophyton floccosum (anthropophilic dermatophyte that can cause athlete's foot and onychomycosis among others), however, it did not show any noteworthy activity against other fungi like Candida albicans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or Cryptococcus neoformans. The antifungal evaluation was performed over cell lines of all the mentioned fungi in an agar dilution method. Scanning electron microscope studies further made the authors conclude that the antifungal mechanism of action is of type wall inhibitor. Similar results of irrelevant activity against S. cerevisiae and C. albicans had been previously obtained27 along with insignificant activity results against the fungi Fusarium oxysporum and Aspergillus niger, however, a 25 μg/mL minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was obtained for the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli and 50 μg/mL MIC for Bacillus subtillis. Derita et al.75 also found some minor activity against Microsporum gypseum, Trichophyton rubrum, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes, all fungi responsible for dermatophytoses.

Tewtrakul et al.53 obtained interesting results concerning the cardamonin ability to inhibit HIV-1 protease, a crucial enzyme in the lifecycle of HIV-1. In this study, cardamonin had an IC50 of 115 μM, while the positive control (acetyl pepstatin) has an IC50 of 0.50 μM. Posterior studies also showed, however, some inhibitor effects over the dengue virus type 2 (DV2) NS3 protease.61 Dengue is still endemic over 100 countries and there is no vaccine available so far or even any specific treatment. No positive control was used in the study; inhibition was assumed using the Lineweaver-Burk plot, whereas cardamonin had a 71% and 39% inhibition rate with a 2 μM dengue-2 protease complex using concentration of 1480 and 444 μM, respectively. Theoretical simulations about how cardamonin interacts with DV2 protease can also be found in literature.90

Miscellaneous

Cho et al.91 showed that cardamonin can inhibit melanogenesis by melanocytes (cells located in the stratum basale of the skin's epidermis). Cardamonin appears to suppress the Wnt signaling pathway and could possibly be used as a potential whitening agent in cosmetics as well as in the treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders.

Huang et al.32 obtained results of antiemetic activity in trials with a young quail, with a 100 mg/Kg dose, they have obtained a 52% inhibition rate.

Recently, Hirata et al.92 observed that cardamonin inhibits cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), the inhibition of this protein leads to the increase of HDL-cholesterol, however, with a significantly lower specific activity (ca. 5 nmol/mg/h) than xanthohumol (ca. 40 nmol/mg/h).

Pandji et al.60 tested if cardamonin could be used in pest control (in trials with neonate larvae of Spodoptera littoralis), however, its efficiency as an insecticide was irrelevant.

Cardamonin metabolism was recently studied28 in human P450 enzymes, results point to the isozymes CYP 1A2 and 2E1. Studies concerning the binding of cardamonin to serum albumin (the most abundant protein in human plasma, very important in the systemic transport of many relevant substances) had already been performed,93 results lead to the conclusion that it binds site II (with an enthalpy change ΔH0 of −25.3 kJ/mol and an entropy change ΔS0 of 7.04 J mol−1 K−1). The binding to lysozyme has also been studied by spectroscopic methods94: enthalpy change ΔH0 of −12.1 kJ/mol and an entropy change ΔS0 of 51.5 J mol−1 K−1. These are relevant information to the development of chalcone-based medication.

Analytical Methods

Zhang et al.29 have analyzed cardamonin by a flow injection analysis method with a chemiluminescence detection based on the reaction between cerium (IV) and rhodamine 6G in an acidic medium, with a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.03 μM.

Wang et al.30 used reverse micelle electrokinetic capillary chromatography to determine the compound with a LOD of 0.7 μM. Liu et al.31 also analyzed it by flow injection–micellar electrokinetic chromatography with a LOD of 13 μM. Recently, a HPLC-UV methodology has been developed with a LOD of 0.52 μM.39

Cardamonin has been analyzed by square wave voltammetry on a hanging mercury drop electrode, the obtained LOD was of 0.55 μM,68 with a peak potential of −1.0 V versus Ag|AgCl.95

It has also been analyzed by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). He et al.28 did in negative mode with the following ions: MS—269, MS2—177, 165, 139, 124. Carvalho et al.68 did in positive mode with the following ions: MS—271, MS2—167, MS3–139; as well as Terreaux et al.70 and Ngo and Brown38: MS—270, 193 and 167; and Itokawa et al.50 270, 269, 253, 193, 131, 103, and 77. It was determined by IR (KBr) first by Krishna and Chaganty22—3170 (-OH), 1625 (C=O), and 970 cm−1 (H-C=C-H)—and later by other authors—3400, 2924, and 1638 cm−1, 74 3154, 1628, 1542, 1486, 1286, 1320, 1224, 1188, 1114, and 926 cm−1, 57 3230, 3032, 2934, 2853, 1628, 1605 cm−1, 38 and 3140, 1630, 1495, 1340, 1220, 1180, 1120, 980, 795, and 750 cm−1.50 1H-NMR results can also be found in literature34,38,39,50,57,65,74 as well as 13C-NMR results.22,50,57,74

Concluding Remarks

Cardamonin is another chalcone becoming increasingly relevant. Some authors claim that it appears to have anti-inflammatory, antineoplastic, vasorelaxant, hypoglycemic, and anti-infectious properties and the quest for potential health applications seems only to grow in the near future as shown clearly by the increasing number of publications. Nevertheless, since the number of articles is not the real qualitative measure of the compound's promising qualities in medicine and, as shown in this article, not all study results are significative (e.g., in some assays, it has shown low-level activity); researchers should be careful when approaching this molecule with high expectations. Furthermore, selectivity has not been fully studied; therefore, numerous side effects might be expected in future pharmaceutical formulations.

So far, cardamonin has been found in many different plants, but the pursuit for a cheap and an easily extractable source of cardamonin might still be of much interest, which will for sure be aided by all the analytical methodologies meanwhile developed.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the Portuguese Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through grant no. PEst-C/EQB/LA0006/2011. IMV (SFRH/BD/69719/2010) and LMG (SFRH/BPD/76544/2011) wish to acknowledge FCT for her PhD studentship and his postdoctoral grant, respectively.

Author Disclosure Statement

All authors declare no competing financial interests or other conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Yadav VR, Prasad S, Sung B, Aggarwal BB: The role of chalcones in suppression of NF-κB-mediated inflammation and cancer. Int Immunopharmacol 2011;11:295–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahu NK, Balbhadra SS, Choudhary J, Kohli DV: Exploring pharmacological significance of chalcone scaffold: a review. Curr Med Chem 2012;19:209–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ni L, Meng CQ, Sikorski JA: Recent advances in therapeutic chalcones. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2004;14:1669–1691 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orlikova B, Tasdemir D, Golais F, Dicato M, Diederich M: Dietary chalcones with chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic potential. Genes Nutr 2011;6:125–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung B, Prasad S, Yadav VR, Aggarwal BB: Cancer cell signaling pathways targeted by spice-derived nutraceuticals. Nutr Cancer 2011;64:173–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle P, Diehm C, Robertson C: Meta-analysis of clinical trials of Cyclo 3 Fort in the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency. Int Angiol 2003;22:250–262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magalhães PJ, Carvalho DO, Cruz JM, Guido LF, Barros AA: Fundamentals and health benefits of xanthohumol, a natural product derived from hops and beer. Nat Prod Commun 2009;4:591–610 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerhauser C, Alt A, Heiss E, et al. : Cancer chemopreventive activity of Xanthohumol, a natural product derived from hop. Mol Cancer Ther 2002;1:959–969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens JF, Page JE: Xanthohumol and related prenylflavonoids from hops and beer: to your good health! Phytochemistry 2004;65:1317–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreira MM, Carvalho AM, Valente IM, et al. : Novel application of square-wave adsorptive-stripping voltammetry for the determination of xanthohumol in spent hops. J Agric Food Chem 2011;59:7654–7658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao X-Y, Hao M, Yang X-Y, et al. : Licochalcone A inhibits growth of gastric cancer cells by arresting cell cycle progression and inducing apoptosis. Cancer Lett 2011;302:69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zi X, Simoneau AR: Flavokawain A, a novel chalcone from kava extract, induces apoptosis in bladder cancer cells by involvement of bax protein-dependent and mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway and suppresses tumor growth in mice. Cancer Res 2005;65:3479–3486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabata K, Motani K, Takayanagi N, et al. : Xanthoangelol, a major chalcone constituent of Angelica keiskei, induces apoptosis in neuroblastoma and leukemia cells. Biol Pharm Bull 2005;28:1404–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guida A, Lhouty MH, Tichit D, Figueras F, Geneste P: Hydrotalcites as base catalysts. Kinetics of Claisen-Schmidt condensation, intramolecular condensation of acetonylacetone and synthesis of chalcone. Appl Catal A Gen 1997;164:251–264 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romanelli G, Pasquale G, Sathicq Á, Thomas H, Autino J, Vázquez P: Synthesis of chalcones catalyzed by aminopropylated silica sol–gel under solvent-free conditions. J Mol Catal A Chem 2011;340:24–32 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cechinel-Filho V, Vaz ZR, Zunino L, Calixto JB, Yunes RA: Synthesis of xanthoxyline derivatives with antinociceptive and antioedematogenic activities. Eur J Med Chem 1996;31:833–839 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eddarir S, Cotelle N, Bakkour Y, Rolando C: An efficient synthesis of chalcones based on the Suzuki reaction. Tetrahedron Lett 2003;44:5359–5363 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vieira LCC, Paixão MW, Corrêa AG: Green synthesis of novel chalcone and coumarin derivatives via Suzuki coupling reaction. Tetrahedron Lett 2012;53:2715–2718 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casiraghi G, Casnati G, Dradi E, Messori R, Sartori G: A general synthesis of 2′-hydroxychalcones from bromomagnesium phenoxides and cinnamic aldehydes. Tetrahedron 1979;35:2061–2065 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schröder J, Raiber S, Berger T, et al. : Plant polyketide synthases: a chalcone synthase-type enzyme which performs a condensation reaction with methylmalonyl-CoA in the biosynthesis of C-methylated chalcones. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1998;37:8417–8425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin MB, Noel JP: The chalcone synthase superfamily of type III polyketide synthases. Nat Prod Rep 2003;20:79–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishna BM, Chaganty RB: Cardamonin and alpinetin from the seeds of Alpinia speciosa. Phytochemistry 1973;12:238 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong H, Chen S-X, Xu H-X, Kadota S, Namba T: A new antiplatelet diarylheptanoid from alpinia blepharocalyx. J Nat Prod 1998;61:142–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Yao XQ, Tsang SY, Lau CW, Chen ZY: Role of endothelium/nitric oxide in vascular response, to flavonoids and epicatechin. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2000;21:1119–1124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le HT, Phan MG, Phan TS: Biologically active phenolic constituents from Alpinia gagnepainii K. Schum (Zingiberaceae). Tap Chi Hoa Hoc 2007;45:126–130 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee J-H, Jung HS, Giang PM, et al. : Blockade of nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway and anti-inflammatory activity of cardamomin, a chalcone analog from Alpinia conchigera. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2006;316:271–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le HT, Phan MG, Phan TS: Further study on chemical constituents and biological activities of Alpinia conchigera Griff. (Zingiberaceae). Tap Chi Hoa Hoc 2007;45:260–264 [Google Scholar]

- 28.He Y-q, Yang L, Liu Y, et al.: Characterization of cardamonin metabolism by P450 in different species via HPLC-ESI-ion trap and UPLC-ESI-quadrupole mass spectrometry. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2009;30:1462–1470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Q, Myint A, Cui H, Ge X, Liu L, Chou G: Determination of cardamonin using a chemiluminescent flow-injection method. Phytochem Anal 2005;16:440–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, Zhou L, He W, Hu Z: Separation and determination of alpinetin and cardamonin by reverse micelle electrokinetic capillary chromatography. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2007;43:1557–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu L, Chen X, Hu Z: Separation and determination of alpinetin and cardamonin in Alpinia katsumadai Hayata by flow injection–micellar electrokinetic chromatography. Talanta 2007;71:155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang WZ, Zhang CF, Zhang M, Wang ZT: A new biphenylpropanoid from Alpinia katsumadai. J Chin Chem Soc 2007;54:1553–1556 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y-Y, Chou G-X, Wang Z-T: New Diarylheptanoids and Kavalactone from Alpinia katsumadai Hayata. Helv Chim Acta 2010;93:382–388 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto N, Kawabata K, Sawada K, et al. : Cardamonin Stimulates Glucose Uptake through Translocation of Glucose Transporter-4 in L6 Myotubes. Phytother Res 2011;25:1218–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao Q, Shi D-H, Zheng W, Xu X-J, Yu Y-H: Antiproliferation of cardamonin is involved in mTOR on aortic smooth muscle cells in high fructose-induced insulin resistance rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2010;641:179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee M-Y, Seo C-S, Lee J-A, et al. : Alpinia katsumadai HAYATA Seed Extract Inhibit LPS-Induced Inflammation by Induction of Heme Oxygenase-1 in RAW264.7 Cells. Inflammation 2012;35:746–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei Z, Yang J, Xia Y-F, Huang W-Z, Wang Z-T, Dai Y: Cardamonin protects septic mice from acute lung injury by preventing endothelial barrier dysfunction. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2012;26:282–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ngo K-S, Brown GD: Stilbenes, monoterpenes, diarylheptanoids, labdanes and chalcones from Alpinia katsumadai. Phytochemistry 1998;47:1117–1123 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao X, Si X, Tong X, Li G: Preparation of flavonoids and diarylheptanoid from Alpinia katsumadai hayata by microwave-assisted extraction and high-speed counter-current chromatography. Sep Purif Technol 2011;81:265–269 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Z-T, Lau C-W, Chan FL, et al. : Vasorelaxant effects of cardamonin and alpinetin from Alpinia henryi K. Schum. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2001;37:596–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nuntawong N, Suksamrarn A: Chemical constituents of the rhizomes of Alpinia malaccensis. Biochem Syst Ecol 2008;36:661–664 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jantan I, Raweh SM, Sirat HM, et al. : Inhibitory effect of compounds from Zingiberaceae species on human platelet aggregation. Phytomedicine 2008;15:306–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jantan I, Pisar M, Sirat HM, et al. : Inhibitory effects of compounds from Zingiberaceae species on platelet activating factor receptor binding. Phytother Res 2004;18:1005–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin E, Lin W-H, Wang S-Y, et al. : Flavokawain B inhibits growth of human squamous carcinoma cells: Involvement of apoptosis and cell cycle dysregulation in vitro and in vivo. J Nutr Biochem 2012;23:368–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohamad H, Abas F, Permana D, et al. : DPPH free radical scavenger components from the fruits of Alpinia rafflesiana Wall. ex. Bak. (Zingiberaceae). Z Naturforsch C 2004;59:811–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chow Y-L, Lee K-H, Vidyadaran S, et al. : Cardamonin from Alpinia rafflesiana inhibits inflammatory responses in IFN-γ/LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia via NF-κB signalling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2012;12:657–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Israf DA, Khaizurin TA, Syahida A, Lajis NH, Khozirah S: Cardamonin inhibits COX and iNOS expression via inhibition of p65NF-κB nuclear translocation and Iκ-B phosphorylation in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Mol Immunol 2007;44:673–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmad S, Israf DA, Lajis NH, et al. : Cardamonin, inhibits pro-inflammatory mediators in activated RAW 264.7 cells and whole blood. Eur J Pharmacol 2006;538:188–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohtsuki T, Kikuchi H, Koyano T, Kowithayakorn T, Sakai T, Ishibashi M: Death receptor 5 promoter-enhancing compounds isolated from Catimbium speciosum and their enhancement effect on TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Biorg Med Chem 2009;17:6748–6754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Itokawa H, Morita M, Mihashi S: Phenolic compounds from the rhizomes of Alpinia speciosa. Phytochemistry 1981;20:2503–2506 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bheemasankara Rao C, Namosiva Rao T, Suryaprakasam S: Cardamonin and alpinetin from the seeds of Amomum subulatum. Planta Med 1976;29:391–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hatziieremia S, Gray AI, Ferro VA, Paul A, Plevin R: The effects of cardamonin on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory protein production and MAP kinase and NFκB signalling pathways in monocytes/macrophages. Br J Pharmacol 2006;149:188–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tewtrakul S, Subhadhirasakul S, Puripattanavong J, Panphadung T: HIV-1 protease inhibitory substances from the rhizomes of Boesenbergia pandurata Holtt. Songklanakarin J Sci Technol 2003;25:503–508 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tewtrakul S, Subhadhirasakul S, Karalai C, Ponglimanont C, Cheenpracha S: Anti-inflammatory effects of compounds from Kaempferia parviflora and Boesenbergia pandurata. Food Chem 2009;115:534–538 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trakoontivakorn G, Nakahara K, Shinmoto H, et al. : Structural analysis of a novel antimutagenic compound, 4-hydroxypanduratin A, and the antimutagenic activity of flavonoids in a Thai spice, fingerroot (Boesenbergia pandurata Schult.) against mutagenic heterocyclic amines. J Agric Food Chem 2001;49:3046–3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murakami A, Kondo A, Nakamura Y, Ohigashi H, Koshimizu K: Possible anti-tumor promoting properties of edible plants from thailand, and identification of an active constituent, cardamonin, of Boesenbergia pandurata. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 1993;57:1971–1973 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sukari MA, Ching AYL, Lian GEC, Rahmani M, Khalid K: Cytotoxic constituents from Boesenbergia pandurata (Roxb.) Schltr. Nat Prod Sci 2007;13:110–113 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Panthong A, Kanjanapothi D, Tuntiwachwuttikul P, Pancharoen O, Reutrakul V: Antiinflammatory activity of flavonoids. Phytomedicine 1994;1:141–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Win NN, Awale S, Esumi H, Tezuka Y, Kadota S: Bioactive Secondary Metabolites from Boesenbergia pandurata of Myanmar and Their Preferential Cytotoxicity against Human Pancreatic Cancer PANC-1 Cell Line in Nutrient-Deprived Medium. J Nat Prod 2007;70:1582–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pandji C, Grimm C, Wray V, Witte L, Proksch P: Insecticidal constituents from four species of the zingiberaceae. Phytochemistry 1993;34:415–419 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kiat TS, Pippen R, Yusof R, Ibrahim H, Khalid N, Rahman NA: Inhibitory activity of cyclohexenyl chalcone derivatives and flavonoids of fingerroot, Boesenbergia rotunda (L.), towards dengue-2 virus NS3 protease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2006;16:3337–3340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morikawa T, Funakoshi K, Ninomiya K, et al. : Medicinal foodstuffs. XXXIV. structures of new prenylchalcones and prenylflavanones with TNF-α and aminopeptidase N inhibitory activities from Boesenbergia rotunda. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2008;56:956–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cao X-D, Ding Z-S, Jiang F-S, et al. : Antitumor constituents from the leaves of Carya cathayensis. Nat Prod Res 2012;26:2089–2094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koorbanally NA, Randrianarivelojosia M, Mulholland DA, Quarles van Ufford L, van den Berg AJJ: Chalcones from the seed of Cedrelopsis grevei (Ptaeroxylaceae). Phytochemistry 2003;62:1225–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aderogba MA, Kgatle DT, McGaw LJ, Eloff JN: Isolation of antioxidant constituents from Combretum apiculatum subsp. apiculatum. S Afr J Bot 2012;79:125–131 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wollenweber E, Kohorst G, Mann K, Bell JM: Leaf Gland Flavonoids in Comptonia peregrina and Myrica pensylvanica (Myricaceae). J Plant Physiol 1985;117:423–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bajgai SP, Prachyawarakorn V, Mahidol C, Ruchirawat S, Kittakoop P: Hybrid flavan-chalcones, aromatase and lipoxygenase inhibitors, from Desmos cochinchinensis. Phytochemistry 2011;72:2062–2067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carvalho AM, Gonçalves LM, Valente IM, Rodrigues JA, Barros AA: Analysis of cardamonin by square wave voltammetry. Phytochem Anal 2012;23:396–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al-Rehaily AJ, Albishi OA, El-Olemy MM, Mossa JS: Flavonoids and terpenoids from Helichrysum forskahlii. Phytochemistry 2008;69:1910–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Terreaux C, Hostettmann MPG, Kurt : Antifungal benzoic acid derivatives from Piper Dilatatum in honour of Professor G. H. Neil Towers 75th birthday. Phytochemistry 1998;49:461–464 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ruiz C, Haddad M, Alban J, et al. : Activity-guided isolation of antileishmanial compounds from Piper hispidum. Phytochem Lett 2011;4:363–366 [Google Scholar]

- 72.López SN, Furlan RLE, Zacchino SA: Detection of antifungal compounds in Polygonum ferrugineum Wedd. extracts by bioassay-guided fractionation. Some evidences of their mode of action. J Ethnopharmacol 2011;138:633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ahmed M, Khaleduzzaman M, Saiful Islam M: Isoflavan-4-ol, dihydrochalcone and chalcone derivatives from Polygonum lapathifolium. Phytochemistry 1990;29:2009–2011 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Derita M, Zacchino S: Chemotaxonomic importance of sesquiterpenes and flavonoids in five argentinian species of Polygonum genus. J Essent Oil Res 2011;23:11–14 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Derita M, Zacchino S: Validation of the ethnopharmacological use of Polygonum persicaria for its antifungal properties. Nat Prod Commun 2011;6:931–933 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.English S, Greenaway W, Whatley FR: Analysis of phenolics in the bud exudates of Populus deltoides, P. fremontii, P. sargentii and P. Wislizenii by GC-MS. Phytochemistry 1992;31:1255–1260 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Greenaway W, Scaysbrook T, Whatley FR: The analysis of bud exudate of populus euramericana, and of propolis, by gas chromatography—mass spectrometry. Proc R S Lond B Biol Sci 1987;232:249–272 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Simirgiotis MJ, Adachi S, To S, et al.: Cytotoxic chalcones and antioxidants from the fruits of Syzygium samarangense (Wax Jambu). Food Chem 2008;107:813–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thuy TT, Porzel A, Ripperger H, Sung TV, Adam G: Chalcones and ecdysteroids from Vitex leptobotrys. Phytochemistry 1998;49:2603–2605 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Economides C, Adam K-P: Lipophilic flavonoids from the fern Woodsia scopulina. Phytochemistry 1998;49:859–862 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takahashi A, Yamamoto N, Murakami A: Cardamonin suppresses nitric oxide production via blocking the IFN-γ/STAT pathway in endotoxin-challenged peritoneal macrophages of ICR mice. Life Sci 2011;89:337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sen R, Baltimore D: Inducibility of κ immunoglobulin enhancer-binding protein NF-κB by a posttranslational mechanism. Cell 1986;47:921–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jin F, Jin X, Jin Y, et al. : Structural requirements of 2′,4′,6′-tris(methoxymethoxy) chalcone derivatives for anti-inflammatory activity: The importance of a 2′-hydroxy moiety. Arch Pharm Res 2007;30:1359–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marques SM, Esteves da Silva JCG: Firefly bioluminescence: a mechanistic approach of luciferase catalyzed reactions. IUBMB Life 2009;61:6–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qin Y, Sun C-Y, Lu F-R, et al. : Cardamonin exerts potent activity against multiple myeloma through blockade of NF-κB pathway in vitro. Leuk Res 2012;36:514–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yadav VR, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB: Cardamonin sensitizes tumour cells to TRAIL through ROS- and CHOP-mediated up-regulation of death receptors and down-regulation of survival proteins. Br J Pharmacol 2012;165:741–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li N, Liu J-H, Zhang J, Yu B-Y: Comparative Evaluation of Cytotoxicity and Antioxidative Activity of 20 Flavonoids. J Agric Food Chem 2008;56:3876–3883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhu JTT, Choi RCY, Chu GKY, et al. : Flavonoids possess neuroprotective effects on cultured pheochromocytoma PC12 Cells: a comparison of different flavonoids in activating estrogenic effect and in preventing β-amyloid-induced cell death. J Agric Food Chem 2007;55:2438–2445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fusi F, Cavalli M, Mulholland D, et al. : Cardamonin is a bifunctional vasodilator that inhibits Cav1.2 current and stimulates KCa1.1 current in rat tail artery myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2010;332:531–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Othman R, Kiat TS, Khalid N, et al. : Docking of noncompetitive inhibitors into dengue virus type 2 protease: understanding the interactions with allosteric binding sites. J Chem Inf Model 2008;48:1582–1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cho M, Ryu M, Jeong Y, et al. : Cardamonin suppresses melanogenesis by inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;390:500–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hirata H, Takazumi K, Segawa S, et al. : Xanthohumol, a prenylated chalcone from Humulus lupulus L., inhibits cholesteryl ester transfer protein. Food Chem 2012;134:1432–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.He W, Li Y, Liu J, Hu Z, Chen X: Specific interaction of chalcone-protein: Cardamonin binding site II on the human serum albumin molecule. Biopolymers 2005;79:48–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.He W, Li Y, Tang J, Luan F, Jin J, Hu Z: Comparison of the characterization on binding of alpinetin and cardamonin to lysozyme by spectroscopic methods. Int J Biol Macromol 2006;39:165–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tavares EM, Carvalho AM, Gonçalves LM, et al. : Chemical sensing of chalcones by voltammetry: trans-chalcone, cardamonin and xanthohumol. Electrochim Acta 2013;90:440–444 [Google Scholar]