Abstract

Both c-Met and VEGFR-2 are important targets for cancer therapies. Here we report a series of potent dual c-Met and VEGFR-2 inhibitors bearing an anilinopyrimidine scaffold. Two novel synthetic protocols were employed for rapid analoguing of the designed molecules for structure–activity relationship (SAR) exploration. Some analogues displayed nanomolar potency against c-Met and VEGFR-2 at enzymatic level. Privileged compounds 3a, 3b, 3g, 3h, and 18a exhibited potent antiproliferative effect against c-Met addictive cell lines with IC50 values ranged from 0.33 to 1.7 μM. In addition, a cocrystal structure of c-Met in complex with 3h has been determined, which reveals the binding mode of c-Met to its inhibitor and helps to interpret the SAR of the analogues.

Keywords: Anilinopyrimidine, dual inhibitor, c-Met, SAR, VEGFR-2

The receptor tyrosine kinase c-Met and its natural ligand hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) generate the c-Met signaling, which promotes the invasive growth during embryonic development, wound healing, and oncogenesis.1 Aberrant expression of c-Met/HGF axis has been detected in a variety of solid tumors.2−5 VEGFR-2 or KDR (kinase insert domain receptor), a member of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs), also belongs to receptor tyrosine kinase family. Its activation by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF0) promotes several key processes required for forming new blood vessels.6,7

c-Met has been shown to synergistically collaborate with VEGFR-2, resulting in promoting angiogenesis of development and progression of various human cancers.8−10 Therefore, molecules that simultaneously inhibit c-Met and VEGFR-2 may be superior to either c-Met-selective or VEGFR-2-selective inhibitor as they can interrupt multiple signaling pathways involved in tumor angiogenesis, proliferation, and metastasis.11

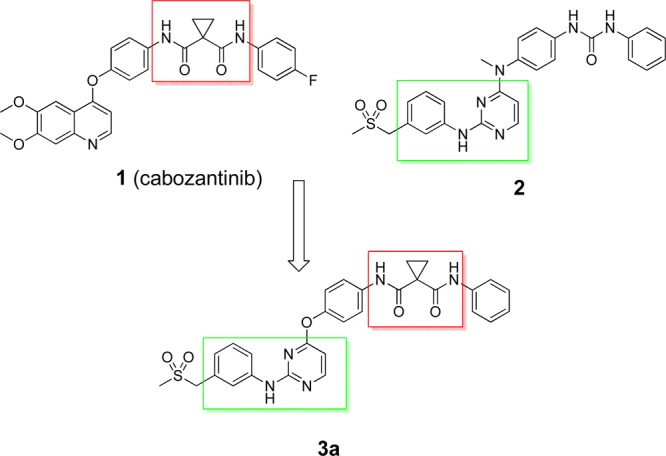

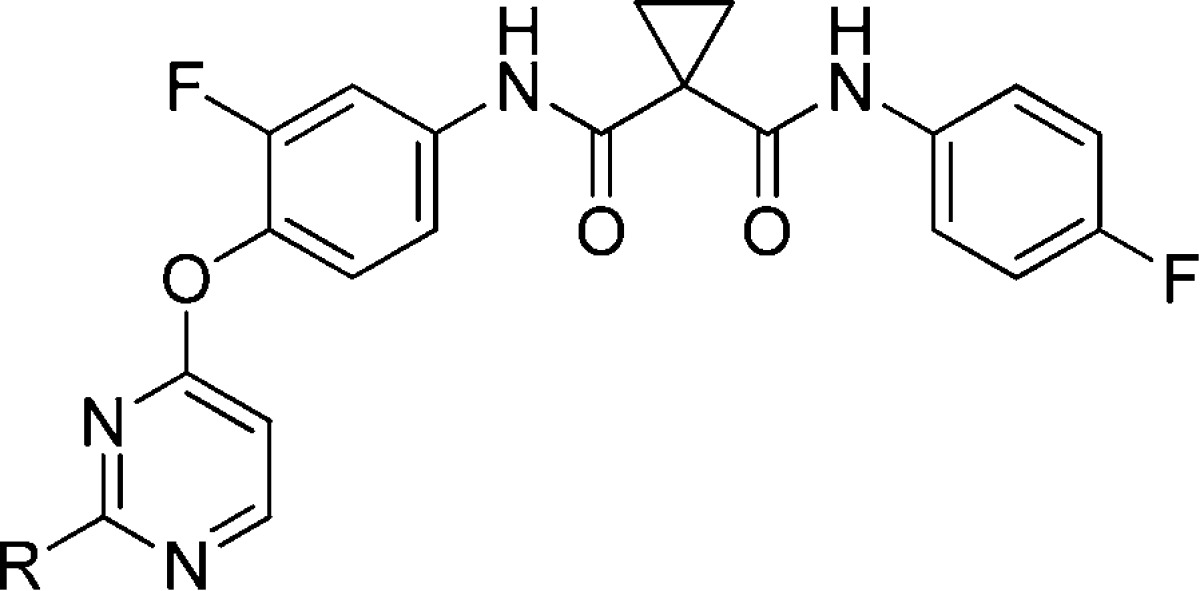

Cabozantinib (1 in Figure 1), an approved drug for the treatment of medullary thyroid cancer, is a highly potent c-Met and VEGFR-2 inhibitor.12,13 A similar compound, dianilinopyrimidine urea 2, was reported only as a potent VEGFR-2 inhibitor with an enzymatic IC50 of 18 nM.14 The difference in the biological profiles of 1 and 2 implied that the cyclopropane-1,1-dicarboxamide moiety might be important for the high inhibition of both c-Met and VEGFR-2 of cabozantinib. On the basis of this assumption, we first designed and synthesized compound 3a, which was a hybrid structure containing both the cyclopropane-1,1-dicarboxamide moiety of cabozantinib and the anilinopyrimidine core structure of 2 (Figure 1). As expected, compound 3a potently inhibited both c-Met and VEGFR-2 with enzymatic IC50 values of 8.8 and 16 nM, respectively. Encouraged by this promising result, we prepared a series of compounds bearing an anilinopyrimidine scaffold to explore their structure–activity relationships (SARs).

Figure 1.

Design of the anilinopyrimidine 3a.

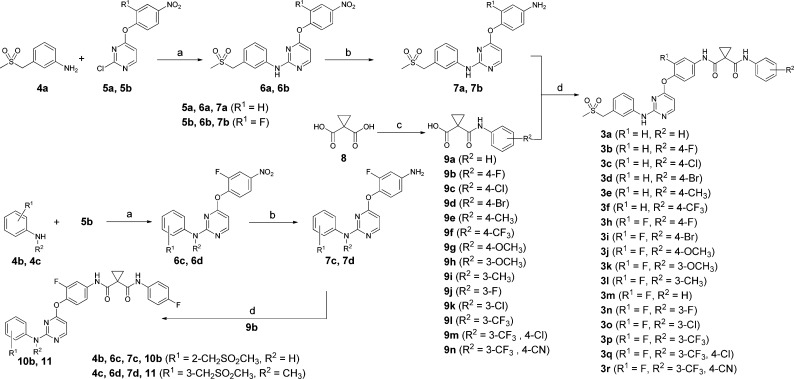

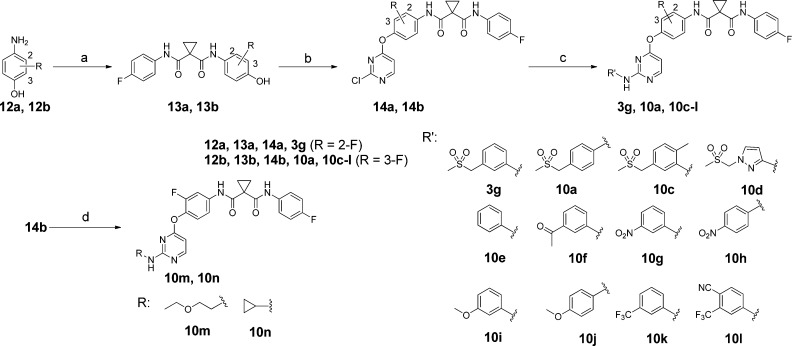

To achieve a rapid structure–activity relationship (SAR) exploration, two efficient synthetic routes were employed for preparation of the analogues. Scheme 1 illustrates the synthesis of 3a–f, 3h–r, 10b, and 11. Intermediates 7a–d were prepared through an acid-catalyzed displacement of chloro compounds 5a and 5b with anilines 4a–4c followed by a reduction reaction with iron powder. The condensation of 7a–d with carboxylic acids 9a–n afforded 3a–f, 3h–r, 10b, and 11. Schemes 2 and 3 outline the synthesis of analogues 3g, 10a, 10c–n, 16a, 16b, and 18a–d. Buchwald–Hartwig reaction of chloro compounds 14a–f with various arylamines provided 3g, 10a, 10c–l, 16a, 16b, 18a, and 18b. However, analogues 10m and 10n were easily prepared from chloro compound 14b with aliphatic amines through SNAr displacement.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 3a–f, 3h–r, 10b, and 11.

Reagents and conditions: (a) p-toluene sulfonic acid monohydrate, DMF, 90 °C for 6a, 6b, and 6d/microwave at 80 °C for 6c; (b) Fe, NH4Cl, EtOH/H2O, reflux; (c) SOCl2, Et3N, THF, then aniline or substituted aniline; (d) EDCI, DMF.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Compounds 3g, 10a, and 10c–n.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 9b, EDCI, DMF; (b) 2,4-dichloropyrimidine, K2CO3, DMF, 80 °C; (c) R’NH2, Xantphos, Pd2(dba)3, Cs2CO3, 1,4-dioxane, 80 °C; (d) RNH2, Et3N, THF, 80 °C.

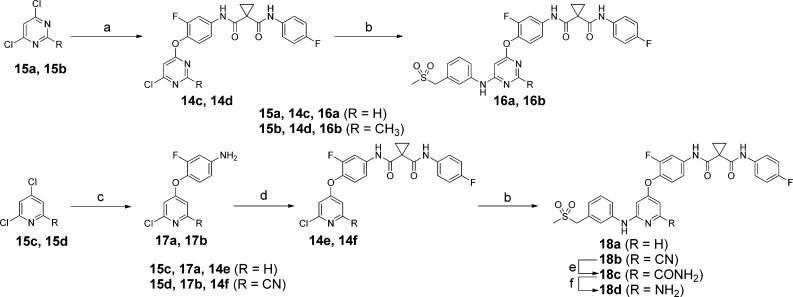

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Compounds 16a, 16b, and 18a–d.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 13b, K2CO3, DMF, 80 °C; (b) 4a, Xantphos, Pd2(dba)3, Cs2CO3, 1,4-dioxane, 80 °C; (c) 12b, KOtBu, DMA, 80 °C; (d) 9b, EDCI, DMF; (e) urea hydrogen peroxide, K2CO3, acetone/H2O; (f) NaOH, NaClO, i-PrOH/H2O.

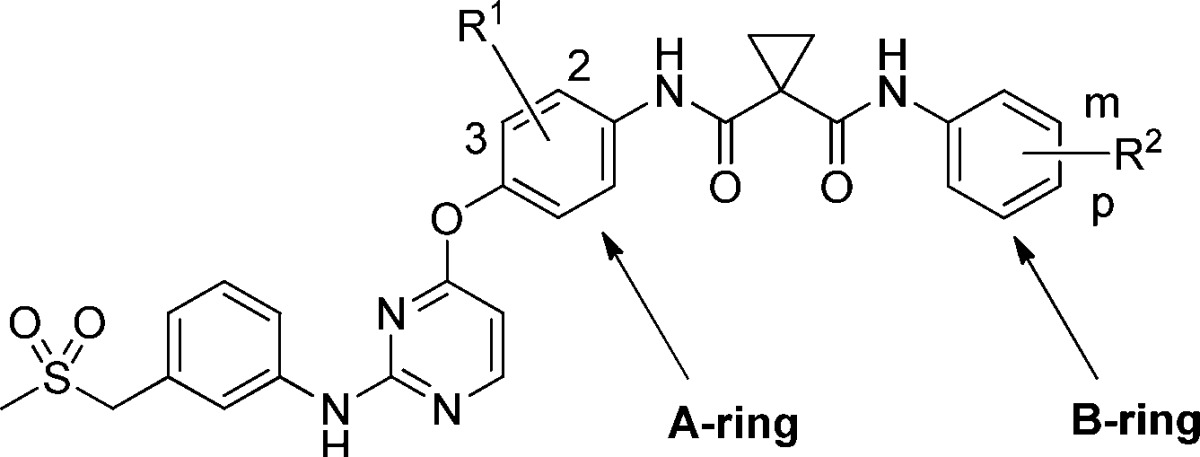

The compounds depicted in Tables 1–3 were assayed with the enzymatic activities against c-Met and VEGFR-2, using PF234106615 and AP2453416 as comparison. The SARs of the analogues with the varied substitutions at A and B rings (Table 1) were first discussed. On the B ring, among the series of para-fluoro, bromo, chloro, methyl, trifluoromethyl substituted analogues (3b–3f), the activity of para-fluoro analogue 3b was equipotent to that of 3a on both c-Met and VEGFR-2, and the other substituents led to a substantial drop in potency on both c-Met and VEGFR-2. Substitution patterns on the B ring of 3h revealed that c-Met was more sensitive to bulky substituents (3i–k, and 3o–r). On the A ring, the 3-fluoro analogue 3h displayed a better enzymatic potency than the 2-fluoro analogue 3g, suggesting that 3-fluoro substitution is superior to 2-fluoro substitution. X-ray crystallography of c-Met and 3h (Figure 2) showed that the hydrophobic pocket where the A ring was accommodated did not tolerate bulky substituents; therefore, no further modification was carried out on the A ring.

Table 1. SAR of A and B Ringsa.

| |

IC50 (nM)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R1 | R2 | VEGFR-2 | c-Met |

| 3a | H | H | 16.0 ± 4.0 | 8.8 ± 1.4 |

| 3b | H | p-F | 14.0 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 0.4 |

| 3c | H | p-Cl | 30.3 ± 4.2 | 32.5 ± 2.1 |

| 3d | H | p-Br | 61.5 ± 8.9 | 66.4 ± 11.2 |

| 3e | H | p-CH3 | 54.0 ± 15.5 | 18.6 ± 4.6 |

| 3f | H | p-CF3 | 219.9 ± 70.3 | 184.0 ± 34.8 |

| 3g | 2-F | p-F | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 13.1 ± 1.6 |

| 3h | 3-F | p-F | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 6.7 ± 0.7 |

| 3i | 3-F | p-Br | 46.6 ± 5.9 | 70.6 ± 0.9 |

| 3j | 3-F | p-OCH3 | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 337.6 ± 4.1 |

| 3k | 3-F | m-OCH3 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 683.1 ± 58.0 |

| 3l | 3-F | m-CH3 | 42.7% @ 10 μM | 81.9 ± 16.9 |

| 3m | 3-F | H | 12.7 ± 2.8 | 25.8 ± 7.7 |

| 3n | 3-F | m-F | 43.0 ± 7.0 | 155.1 ± 19.4 |

| 3o | 3-F | m-Cl | 9.8 ± 0.3 | 212.7 ± 9.7 |

| 3p | 3-F | m-CF3 | 48.0 ± 8.0 | 234.3 ± 22.2 |

| 3q | 3-F | m-CF3, p-Cl | 83.6 ± 0.9 | 791.9 ± 169.2 |

| 3r | 3-F | m-CF3, p-CN | 44.5 ± 7.5 | 17.7% @ 10 μM |

See Supporting Information for a description of the assay conditions.

c-Met IC50 of PF2341066 = 1.5 ± 0.3 nM; VEGFR-2 IC50 of AP24534 = 4.3 ± 0.4 nM.

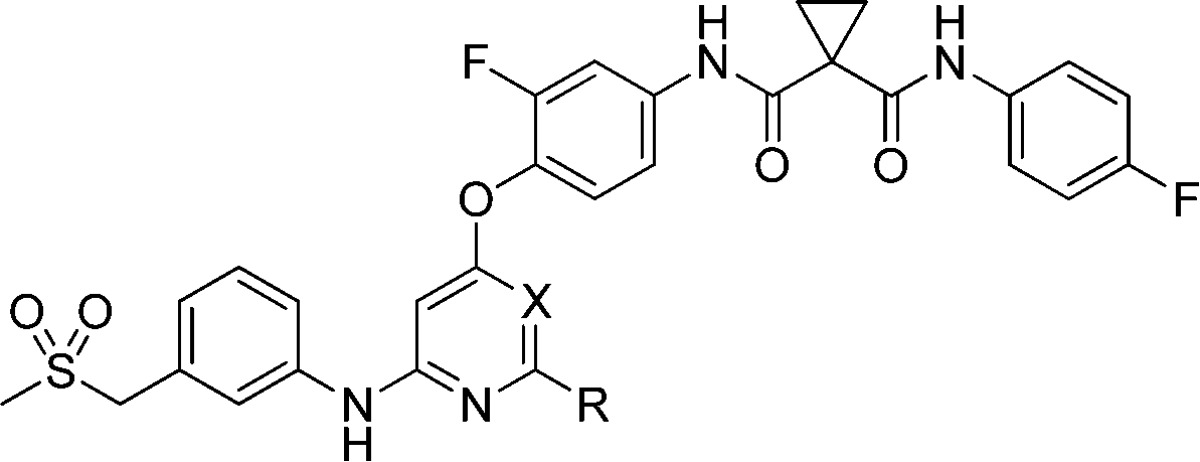

Table 3. SAR of Pyrimidine Derivativesa.

| |

IC50 (nM)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R | X | VEGFR-2 | c-Met |

| 3h | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 6.7 ± 0.7 | ||

| 16a | H | N | 55.0 ± 13.0 | 21.7 ± 1.0 |

| 16b | CH3 | N | 37.4% @ 10 μM | 924.0 ± 9.8 |

| 18a | H | CH | 16.0 ± 3.0 | 3.8 ± 0.5 |

| 18b | CN | CH | 0 @ 10 μM | 805.8 ± 98.1 |

| 18c | CONH2 | CH | 3.1% @ 10 μM | 211.1 ± 67.2 |

| 18d | NH2 | CH | 0 @ 10 μM | 39.6% @ 10 μM |

See Supporting Information for a description of the assay conditions.

c-Met IC50 of PF2341066 = 1.5 ± 0.3 nM; VEGFR-2 IC50 of AP24534 = 4.3 ± 0.4 nM.

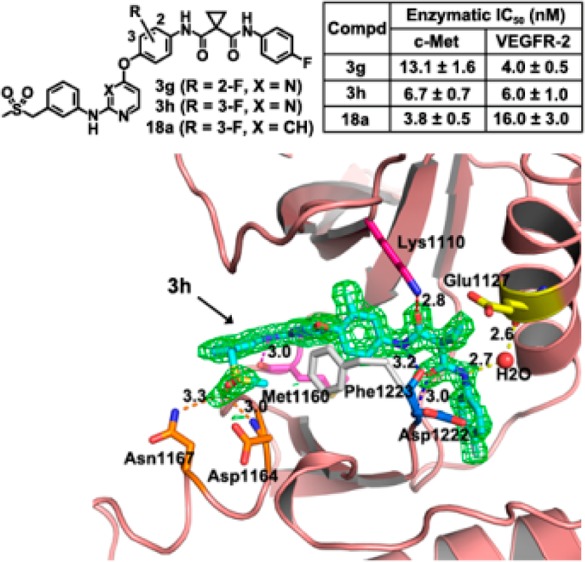

Figure 2.

Cocrystal structure of the compound 3h in complex with the kinase domain of c-Met. The pdb code of the structure is 4MXC. (A) An overview of the complex structure. The molecular surface of 3h buried into the kinase domain is represented by dots, and the compound is shown by sticks. (B) The hydrogen bond interactions (dash lines) as well as the π–π stacking interactions between 3h and residues of c-Met.

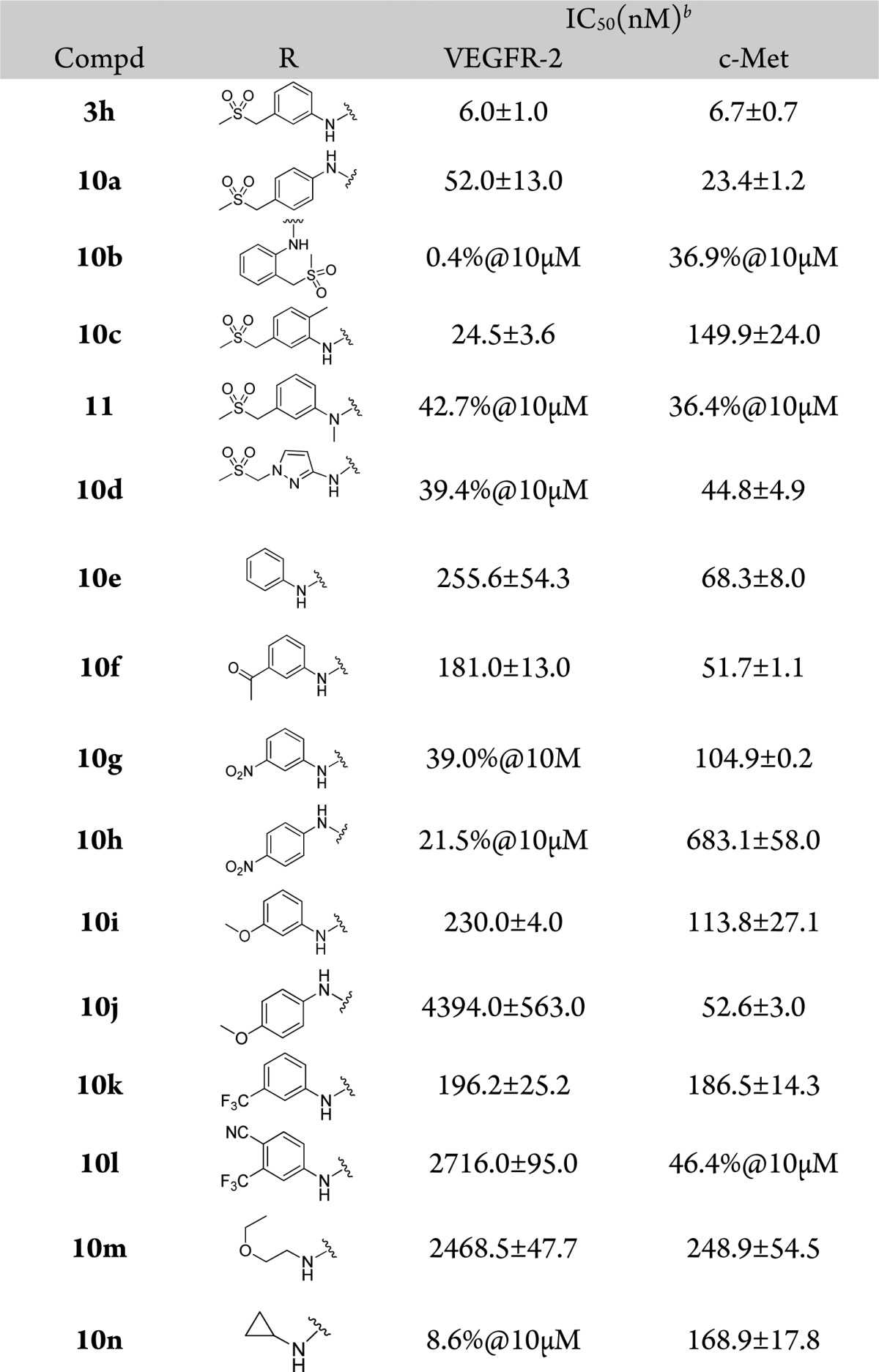

With optimized A and B rings, we then investigated SARs on the 2-position of the pyrimidine of 3h (Table 2). The para- and ortho-methylsulfonylmethyl analogues (10a and 10b) displayed a lower potency than their meta-substituted counterpart 3h in both VEGFR-2 and c-Met, indicating that meta substitution is preferred in this series of compounds. Compound 10e was prepared to test the impact of removal of the methylsulfonylmethyl on its activity, and the result showed that this modification led to a sharp drop in potency on both c-Met and VEGFR-2. The drop in potency can be explained by the fact that the hydrogen bond between the methylsulfonyl oxygen and the backbone NH of Asp 1164 was essential for maintaining c-Met potency as was confirmed by the crystal structure of c-Met and 3h (Figure 2B). To examine the role of NH in the anilinopyrimidine moiety on the activity, we prepared an N-methylated analogue 11, but it was inactive against both c-Met and VEGFR-2. The loss of potency might be attributed to the loss of the hydrogen bond between NH and the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Met 1160 in the hinge region as shown in Figure 2B. Variations of substituents on the 2-position of pyrimidine were then examined. Much to our disappointment, substitution of meta-methylsulfonylmethylphenyl with methylsulfonylmethylpyrazolyl (10d), acetylphenyl (10f), nitrophenyl (10g and 10h), trifluoromethylphenyl (10k and 10l), and two alkyl (10m and 10n) ended up with poor potencies in both c-Met and VEGFR-2. Therefore, we concluded that both the 3-methylsulfonylmethylaniline and N-(3-fluoro-phenyl)-N′-(4-fluoro-phenyl)cyclopropane-1,1-dicarboxamide moieties were crucial to the analogues for good potencies on both c-Met and VEGFR-2 as shown by the data in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 2. SAR of 2-Substituents on the Pyrimidine Ringa.

See Supporting Information for a description of the assay conditions.

c-Met IC50 of PF2341066 = 1.5 ± 0.3 nM; VEGFR-2 IC50 of AP24534 = 4.3 ± 0.4 nM.

As an extension of the 2,4-disubstitued pyrimidine chemotype, 4,6-disubstituted pyrimidine analogues and 2,4-disubstituted pyridine analogue were also explored (Table 3). The result showed that the 4,6-disubstituted pyrimidine analogues (16a and 16b) exhibited decreased c-Met and VEGFR-2 potencies and that the pyridine analogue 18a inhibited c-Met with an IC50 value of 3.8 nM, a moderate improvement compared to 3h. The crystal of 3h in complex with the kinase domain of c-Met revealed that 3h occupied the ATP-binding site as well as an adjacent pocket of the kinase domain and trapped the kinase in its inactive conformation (Figure 2A).17 The details of the hydrogen bonds were shown in Figure 2B. In particular, a π–π stacking interaction occurred between the phenyl ring of Phe1223 and the central fluorophenyl group of 3h, which dislodges Phe1223 of the DFG motif from its activated conformation.17

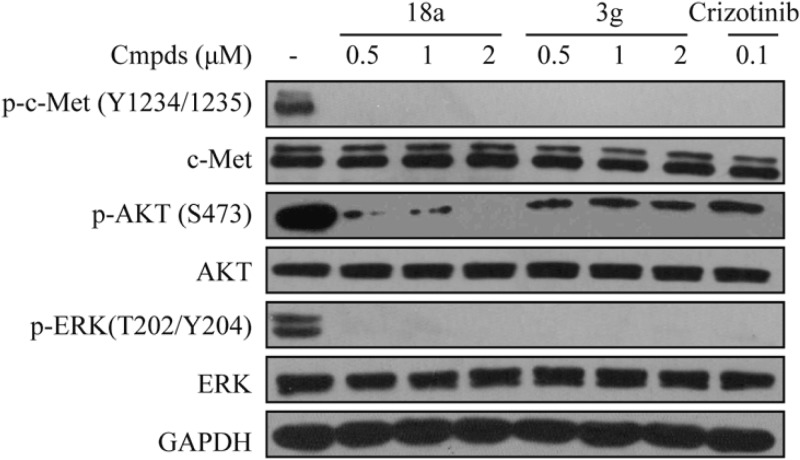

The cellular assays commenced by testing the activities of the compounds with good enzymatic potencies (3a, 3b, 3g, 3h, and 18a) in MKN-45 gastric carcinoma cells. As shown in Table 4, compounds 3g and 18a outperformed the other counterparts with IC50 values of 0.59 and 0.46 μM, respectively. Moreover, 3g and 18a also demonstrated strong inhibition in EBC-1 (human nonsmall-cell lung cancer cell line) cells, though the assayed compounds suffered a decrease in enzyme-to-cell shift, which might be ascribed to the poor cellular penetration. In an immunoblot analysis of compound 3g or 18a treated EBC-1 cells, complete inhibition of c-Met phosphorylation was observed at a concentration of 0.5 μM (Figure 3). In addition, c-Met downstream signaling molecules (Erk 1/2 and AKT) were also significantly suppressed.18 These data suggest that inhibition of the phosphorylation of c-Met as well as the subsequent c-Met downstream signaling accounts for the antiproliferative potency of compounds 3g and 18a.

Table 4. Effects of Selected Analogues on Human Cancer Cell Proliferationa.

| IC50 (μM) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Compd | MKN-45 | EBC-1 |

| 3a | 1.7 ± 0.04 | |

| 3b | 1.3 ± 0.28 | |

| 3g | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 0.72 ± 0.04 |

| 3h | 1.1 ± 0.05 | |

| 18a | 0.46 ± 0.001 | 0.33 ± 0.01 |

See Supporting Information for a description of the assay conditions.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of c-Met phosphorylation and related signaling pathways by compound 3g and 18a in EBC-1 cells.

In summary, a series of novel and potent dual c-Met/VEGFR-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitors bearing an anilinopyrimidine scaffold were designed and synthesized. Systematic SAR allowed us to identify several very potent c-Met/VEGFR-2 dual inhibitors. In addition to their enzymatic activities, the privileged compounds 3g and 18a demonstrated potent antiproliferative activities in MKN-45 and EBC-1 cancer cells, as well as inhibition of c-Met phosphorylation and its downstream signaling pathways in EBC-1 cells. Besides, the X-ray structure reveals that 3h occupies the ATP-binding site as well as an adjacent pocket of c-Met kinase domain in an inactive conformation. Although none of our designed derivatives are better than cabozantinib at both enzymatic and cellular levels, this study has provided us with the clear SARs that are responsible for inhibition of c-Met/VEGFR-2 and will aid in the design of more potent dual c-Met/VEGFR-2 inhibitors.

Supporting Information Available

Synthetic procedures and analytical data for compounds reported in this letter, procedures for enzymatic and cellular assays, and procedures for X-ray cocrystallization. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

∥ (Z.Z., J.A., and Q.L.) These authors contributed equally to this work.

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81273365 and 81102461), Major Projects in National Science and Technology of China (no. 2010ZX09401-401, 2012ZX09103101-024, and 2012ZX09301001-007), National Program on Key Basic Research Project of China (2012CB910704), and the ″100 Talents Project″ of CAS (to Y.X.) for their financial support.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Comoglio P. M.; Giordano S.; Trusolino L. Drug development of MET inhibitors: targeting oncogene addiction and expedience. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 504–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchmeier C.; Birchmeier W.; Gherardi E.; VandeWoude G. F. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 915–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H.-L.; Trink B.; Tzai T.-S.; Liu H.-S.; Chan S.-H.; Ho C.-L.; Sidransky D.; Chow N.-H. Overexpression of c-MET as a prognostic indicator for transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a comparison with p53 nuclear accumulation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 1544–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka T.; Takayama H.; Sharp R.; Celli G.; LaRochelle W. J.; Bottaro D. P.; Ellmore N.; Vieira W.; Owens J. W.; Anver M.; Merlino G. c-Met autocrine activation induces development of malignant melanoma and acquisition of the metastatic phenotype. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 5157–5167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drebber U.; Baldus S. E.; Nolden B.; Grass G.; Bollschweiler E.; Dienes H. P.; Hölscher A. H.; Mönig S. P. Overexpression of c-MET as a prognostic indicator for gastric carcinoma compared to p53 and p21 nuclear accumulation. Oncol. Rep. 2008, 19, 1477–1483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin. Oncol. 2002, 296 Suppl. 1615–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in the regulation of angiogenesis. Kidney Int. 1999, 56, 794–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N.; Gerber H. P.; LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannion M.; Raeppel S.; Claridge S.; Zhou N.; Saavedra O.; Isakovic L.; Zhan L.; Gaudette F.; Raeppel F.; Déziel R.; Beaulieu N.; Nguyen H.; Chute I.; Beaulieu C.; Dupont I.; Robert M.-F.; Lefebvre S.; Dubay M.; Rahil J.; Wangd J.; Ste-Croix H.; Macleod A. R.; Besterman J. M.; Vaisburg A. N-(4-(6,7-Disubstituted-quinolin-4-yloxy)-3-fluorophenyl)-2-oxo-3-phenylimidazolidine-1-carboxamides: A novel series of dual c-Met/VEGFR2 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 6552–6556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claridge S.; Raeppel F.; Granger M.-C.; Bernstein N.; Saavedra O.; Zhan L.; Llewellyn D.; Wahhab A.; Deziel R.; Rahil J.; Beaulieu N.; Nguyen H.; Dupont I.; Barsalou A.; Beaulieu C.; Chute I.; Gravel S.; Robert M.-F.; Lefebvre S.; Dubay M.; Pascal R.; Gillespie J.; Jin Z.; Wang J.; Besterman J. M.; MacLeodb A. R.; Vaisburga A. Discovery of a novel and potent series of thieno[3,2-b]pyridine-based inhibitors of c-Met and VEGFR2 tyrosine kinases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 2793–2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilanges B.; Torbett N.; Vanhaesebroeck B. Killing two kinase families with one stone. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 648–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes F. M.; Chen J.; Tan J.; Yamaguchi K.; Shi Y.; Yu P.; Qian F.; Chu F.; Bentzien F.; Cancilla B.; Orf J.; You A.; Laird A. D.; Engst S.; Lee L.; Lesch J.; Chou Y.-C.; Joly A. H. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 10, 2298–2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzrock R.; Sherman S. I.; Ball D. W.; Forastiere A. A.; Cohen R. B.; Mehra R.; Pfister D. G.; Cohen E. E. W.; Janisch L.; Nauling F.; Hong D. S.; Ng C. S.; Ye L.; Gagel R. F.; Frye J.; Müller T.; Ratain M. J.; Salgia R. Activity of XL184 (Cabozantinib), an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with medullary thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2660–2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammond D. M.; Nailor K. E.; Veal J. M.; Nolte R. T.; Wang L.; Knick V. B.; Rudolph S. K.; Truesdale A. T.; Nartey E. N.; Stafford J. A.; Kumar R.; Cheung M. Discovery of a novel and potent series of dianilinopyrimidineurea and urea isostere inhibitors of VEGFR2 tyrosine kinase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 3519–3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J. J.; Tran-Dubé M.; Shen H.; Nambu M.; Kung P. P.; Pairish M.; Jia L.; Meng J.; Funk L.; Botrous I.; McTigue M.; Grodsky N.; Ryan K.; Padrique E.; Alton G.; Timofeevski S.; Yamazaki S.; Li Q.; Zou H.; Christensen J.; Mroczkowski B.; Bender S.; Kania R. S.; Edwards M. P. Structure based drug design of crizotinib (PF-02341066), a potent and selective dual inhibitor of mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (c-MET) kinase and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6342–6363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare T.; Shakespeare W. C.; Zhu X.; Eide C. A.; Rivera V. M.; Wang F.; Adrian L. T.; Zhou T.; Huang W. S.; Xu Q.; Metcalf C. A. III; Tyner J. W.; Loriaux M. M.; Corbin A. S.; Wardwell S.; Ning Y.; Keats J. A.; Wang Y.; Sundaramoorthi R.; Thomas M.; Zhou D.; Snodgrass J.; Commodore L.; Sawyer T. K.; Dalgarno D. C.; Deininger M. W.; Druker B. J.; Clackson T. AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 401–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Gray N. S. Rational design of inhibitors that bind to inactive kinase conformations. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2, 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertotti A.; Burbridge M. F.; Gastaldi S.; Galimi F.; Torti D.; Medico E.; Giordano S.; Corso S.; Rolland-Valognes G.; Lockhart B. P.; Hickman J. A.; Comoglio P. M.; Trusolino L. Only a subset of Met-activated pathways are required to sustain oncogene addiction. Sci. Signaling 2009, 2, ra80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.