Abstract

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is the most popular cyanobacterial model for prokaryotic photosynthesis and for metabolic engineering to produce biofuels. Genomic and transcriptomic comparisons between closely related bacteria are powerful approaches to infer insights into their metabolic potentials and regulatory networks. To enable a comparative approach, we generated the draft genome sequence of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6714, a closely related strain of 6803 (16S rDNA identity 99.4%) that also is amenable to genetic manipulation. Both strains share 2838 protein-coding genes, leaving 845 unique genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and 895 genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6714. The genetic differences include a prophage in the genome of strain 6714, a different composition of the pool of transposable elements, and a ∼40 kb genomic island encoding several glycosyltransferases and transport proteins. We verified several physiological differences that were predicted on the basis of the respective genome sequence. Strain 6714 exhibited a lower tolerance to Zn2+ ions, associated with the lack of a corresponding export system and a lowered potential of salt acclimation due to the absence of a transport system for the re-uptake of the compatible solute glucosylglycerol. These new data will support the detailed comparative analyses of this important cyanobacterial group than has been possible thus far. Genome information for Synechocystis sp. PCC 6714 has been deposited in Genbank (accession no AMZV01000000).

Keywords: comparative genomics, cyanophages, genome sequence, prophage, salt acclimation

1. Introduction

Genomic and transcriptomic comparisons between closely related bacteria are powerful approaches to infer insight into the metabolic potentials and regulatory networks. Among cyanobacteria, this has been illustrated by detailed comparative analyses of the marine picoplanktonic cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus.1–3 However, due to the lack of data from closely related strains, no comprehensive comparison has focused on Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (from here on Synechocystis 6803), the otherwise most popular cyanobacterial system to work with. Synechocystis 6803 was the first phototrophic and the third organism overall for which a complete genome sequence was determined.4 The genome of Synechocystis 6803 was manually curated by the research community at CyanoBase (http://genome.microbedb.jp/cyanobase/Synechocystis).5 Over the years, several substrains of 6803 evolved in different laboratories showing distinct physiological features (e.g. glucose tolerance), from which also several have recently been re-sequenced.6–9

The coverage with analysed genome sequences for the cyanobacterial phylum has been greatly improved recently. Based on a diversity-driven selection of species for genome sequencing, 54 additional strains were analysed,10 raising the number of publicly available cyanobacterial genome sequences to 126. With strain PCC 7509 also, one Synechocystis strain was sequenced. However, it is only very remotely related (90% 16S rRNA identity) to Synechocystis 6803 and belongs even to another clade (B1) than Synechocystis 6803 (B2) in the cyanobacterial tree.10 Therefore, despite its naming as Synechocystis, the strain PCC 7509 is quite distant from Synechocystis 6803. In the current cyanobacterial tree, Synechocystis 6803 is sharing a clade with unicellular N2-fixing oceanic strains such as Cyanothece spp.10 It has been reported that a 97–100% 16S rRNA identity is necessary for a productive genome comparison among strains.1–3

Thus, Synechocystis 6803 lacked a closely related organism with a known genome sequence that appeared suitable for comparative analysis. To fill this gap, we selected Synechocystis sp. PCC 6714 (from here: Synechocystis 6714) as candidate. Synechocystis 6803 as well as strain 6714 are unicellular cyanobacteria that were isolated from the same freshwater pond in Oakland, California, by R. Kunisawa. These strains were initially part of the ‘Berkeley Culture Collection’,11 which were later transferred into the ‘Pasteur Culture Collection’ of cyanobacteria.12 The decision to choose Synechocystis 6714 was further supported by the high 16S rRNA identity (99.4%) among the two strains, thus well suited for comparative analyses. Their close genetic relation also was seen in an expression-based screen that revealed the presence of a highly transcribed CRISPR system in it,13 similar to the one in Synechocystis 6803.14 Moreover, the strain 6714 also represents an established laboratory strain, amenable to genetic manipulation.15,16

Here, we focus on the draft genome analysis of Synechocystis 6714 in comparison to strain 6803. In a parallel study, we will provide the primary transcriptomes of both strains under 10 different conditions using strand-specific cDNA sequencing.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Genome sequencing, assembly, gap closure, and annotation

Synechocystis 6714 was purchased from the Pasteur Culture Collection (PCC) in Paris, France. Genomic DNA was extracted as described earlier.9 We prepared two libraries for sequencing, one with fragment lengths of 160 nt for paired-end sequencing and one with ∼3 kb long fragments, which was used for preparing a mate pair library (Illumina Mate Pair Library Prep Kit, catalogue no. PE-112-2002). Both libraries were subjected to paired-end sequencing, yielding 135 969 158 reads of 101 nt length. The accumulated sequence information resulted in a nearly 2000-fold coverage when expecting a genome of 3.5 Mb. The reads were assembled with velvet17 using a kmer-length of 85, a coverage cut-off at 5, and an expected coverage of 1300. This resulted in 74 contigs arranged in five scaffolds longer than 10 000 nt. Gaps within scaffolds were analysed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and subsequent Sanger sequencing and, if successful, closed with the obtained sequence information. This removed 19 gaps reducing the number to 55. Gene prediction and annotation was done with RAST18 and led to the prediction of 3733 protein coding genes, 40 tRNAs, and 1 cluster of ribosomal RNAs.

2.2. Orthologue prediction

Orthologue prediction was based on the 3733 open reading frames (ORFs) from Synechocystis 6714 and 3683 ORFs from Synechocystis 6803, resulting from a combination of all ORFs from Mitschke et al., Supplementary data file S119 and all plasmid-located ORFs annotated in CyanoBase5 [accession nos. AP004311, AP004312, AP004310, AP006585, L13739, L25424, and pCC5.2 (without accession no.)]. Orthologues of protein coding genes were identified using a reciprocal best blast hit (RBH) strategy. For the identification of gene families and unique genes, we used Markov clustering (MCL)20 on the results of reciprocal BlastP searches. Clustering into protein families using the MCL algorithm yielded 2413 shared protein families with 3385 and 3187 members in Synechocystis 6803 and 6714, respectively. Putative transposase genes were identified by BLASTp searches against the ISfinder21 requiring a BLASTp value of ≤1e10−8.

2.3. Physiological experiments

In addition to Synechocystis 6714, we used Synechocystis 6803 substrain ‘PCC-M’9 for comparative physiological experiments. Liquid cultures were grown at 30°C in liquid BG11 medium12 under continuous white light illumination of 50–80 µmol quanta m−2 s−1. For growth on solid medium, BG11 was supplemented with 0.9% agar (Kobe I, Roth, Germany). Salt-dependent growth, GG contents, and mRNA patterns were measured for cultures of 300 ml volume that were grown under constant shaking in 500 ml Erlenmeyer flasks. The cells were pre-cultivated for 2 days at standard conditions before sterile, crystalline NaCl was added to a final concentration of 2, 4, and 6% (w/v), respectively. After 4 days, 50 ml of cells was harvested by rapid filtration on hydrophilic polyethersulfone filters (Pall Supor 800 Filter, 0.8 µm). The adherent cell material was immediately dissolved in 1 ml of PGTX solution22 and total RNA was extracted as described.13 For the measurement of glucosylglycerol content, 2 ml of cells was harvested by centrifugation and soluble metabolites were extracted with 80% ethanol (HPLC gradient, Roth, Germany). The supernatant was freeze-dried. The cell extract was then purified from insoluble material by centrifugation and the supernatant was also freeze-dried. Both, the dried cell extracts and external fractions were resuspended in A. dest (HPLC gradient, Roth, Germany), centrifuged and the supernatant was freeze-dried again. Samples were then analysed by gas chromatography as previously described.23

2.4. Northern blot analysis

For expression analysis, 3 µg of total RNA was separated on 1.5% agarose gels, transferred to Hybond-N nylon membranes by capillary blotting and cross-linked by UV-illumination. The membranes were hybridized with 32P-labelled RNA probes generated from specific DNA templates by using Ambion® MAXIscript® T7 In Vitro Transcription Kit as described earlier.24 The oligonucleotide sequences used for the generation of DNA templates by PCR are given in Supplementary Table S1. Signals were visualized with the Personal Molecular Imager FX system and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Draft genome of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6714

The genome of Synechocystis 6714 was sequenced using two libraries of different lengths by paired-end sequencing and assembled into five scaffolds ranging from 46 504 to 2 984 476 nt in length. The DNA is characterized by an average GC content of 47.37%, which is very close to the value of 47.4% reported for strain 6714 in 1971 based on CsCl density gradient equilibrium centrifugation.11 The longest scaffold C2 likely represents the major part of the chromosome, since it closely resembles the chromosome of strain 6803. Table 1 summarizes the main features of the draft genome. Since the scaffolds C0 and C4 carry tRNA genes and the majority of their protein-coding genes have orthologues on the chromosome of Synechocystis 6803, they also are likely part of the chromosome. This assumption also is in line with their 3 and 5% higher GC content compared with the scaffolds C1 and C3. For comparison, the GC content of the Synechocystis 6803 chromosome is 47.72%, whereas it also is lower for three out of the four large plasmids (pSYSX, 42.72%; pSYSA, 44.48%, pSYSM, 42.95%).25 By combining the scaffolds C0, C2, and C4, we estimated the size of the Synechocystis 6714 chromosome to be around 3.45 Mb, which is fairly similar to the 3.57 Mb of Synechocystis 6803.

Table 1.

Summary of the Synechocystis 6714 draft genome main features

| Scaffold | Size (nt) | Genes | GC % | tRNA genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0 | 189 995 | 183 | 47.79 | 2 |

| C1 | 181 306 | 201 | 42.41 | 0 |

| C2 | 2 985 628 | 3034 | 47.72 | 35 |

| C3 | 46 504 | 45 | 44.25 | 0 |

| C4 | 287 195 | 270 | 47.13 | 4 |

| Total | 3 690 628 | 3733 | 47.37 | 41 |

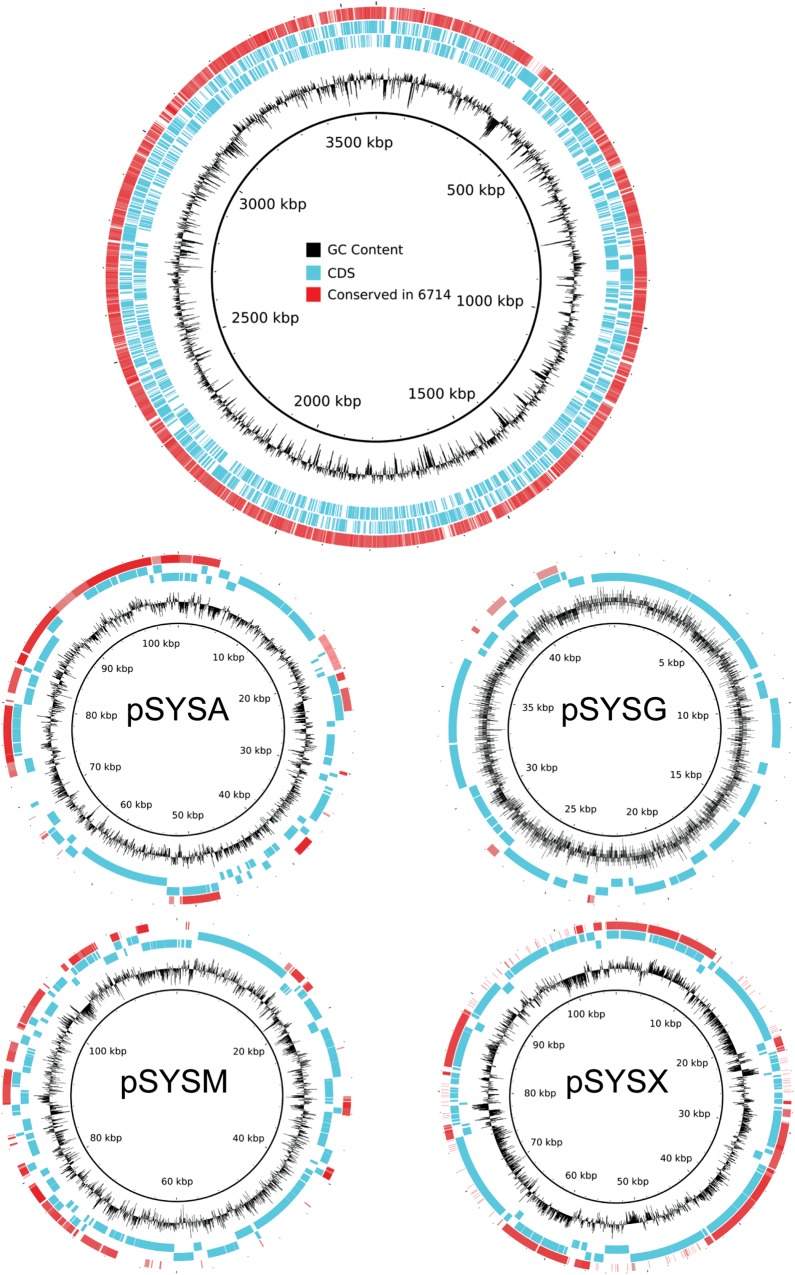

Compared with the rather high similarity of the chromosome size and coding capacity, the similarities of plasmid sequences were rather low between the two strains. Among the seven plasmids25–28 of Synechocystis 6803, we found no significant similarities toward its plasmids pSYSG, pCC5.2, pCA2.4, and pCB2.4 in strain 6714. In contrast, sequences resembling about one-third each of pSYSA, pSYSM, and pSYSX of Synechocystis 6803 were detected in strain 6714 (Fig. 1). Thus, our draft genome points at a different composition or lower coding capacity of extrachromosomal plasmids in strain 6714 compared with strain 6803.

Figure 1.

Genome coverage based on circular genome plots of the Synechocystis 6803 chromosome and its four large plasmids pSYSA, pSYSG, pSYSM ,and pSYSX. Tracks from the outside show (1) regions with BLASTN hit in Synechocystis 6714 and identity between 50% (grey) and 100% (red); (2) CDS features from forward and reverse strand in Synechocystis 6803; (3) GC content.

A marked difference between both strains exists in the number and types of mobile genetic elements (Table 2). Synechocystis 6803 possesses at least 134 genes encoding transposases. These transposases, which were identified by BLASTp searches against the ISfinder database,21 requiring a BLASTp E-value of ≤10–8, were assigned to 11 different families, each containing 1–45 identical copies. The highest copy numbers were found for the IS630, IS5, and IS701 families of IS elements (Table 2, Supplementary Table S2). In Synechocystis 6714, we identified only 32 transposase genes, which belong to only six different families. The highest copy numbers were found for the IS200/IS605 family and as before in strain 6803 for IS630 and IS5 families (Table 2, Supplementary Table S3). At a first glance, this high divergence in the numbers and types of insertion sequences appears surprising, given the otherwise close relatedness among the two strains. However, this finding is in line with reports for the ISY203 group of elements (belonging to the IS4 family) that vary even among substrains of 6803. Four members of this IS element with identical nucleotide sequences were present only in the ‘Kazusa’ substrain, whereas they were absent in the genomes of other substrains.29

Table 2.

Types and numbers of IS elements found on basis of identified transposase genes

| IS element | Strain 6803 | Strain 6714 |

|---|---|---|

| IS1 | 10 | 0 |

| ISTcSa | 3 | 0 |

| IS3 | 1 | 0 |

| ISL3 | 3 | 0 |

| IS4 | 14 | 0 |

| IS200/IS605 | 1 | 5 |

| IS256 | 2 | 1 |

| IS5 | 31 | 7 |

| IS630 | 45 | 11 |

| IS701 | 23 | 3 |

| Tn3 | 0 | 2 |

| ISLre2 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 134 | 32 |

Using RBH, we identified 2838 orthologous protein-coding genes between Synechocystis 6714 and 6803, leaving 845 specific genes in strain 6803 and 895 specific genes in strain 6714. Thus, among the two strains, more than 75% of the genes are conserved. However, many of the strain-specific genes belong to gene families that were clustered as paralogues to pairs of orthologue genes when using the MCL algorithm,20 indicating gene duplications, sequence, and probably also functional diversification. The full list of orthologue and paralogue genes between the two strains is presented in Supplementary Table S4. In Supplementary Tables S5 and S6, we present the lists of unique protein-coding genes. Only 537 of the 845 Synechocystis-6803-specific genes are located on the chromosome (=16% of all chromosomal protein-coding genes; Supplementary Table S5), whereas 308 of the genes lacking a clear orthologue (=76% of all plasmid-located protein-coding genes in 6803) can be explained by the strong differences in the plasmid-located gene pool. Moreover, it should be noted that the majority of strain-specific genes encodes for proteins of unknown function, i.e. the functional significance of the majority of differences is thus uncertain.

3.2. Large-scale differences between Synechocystis 6803 and Synechocystis 6714: unique genetic arrangements in a large genomic island and prophage Psy1

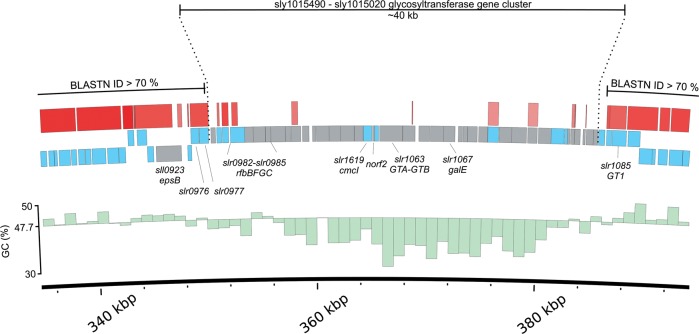

The higher number of transposon genes in Synechocystis 6803 is correlated with a low degree of syntheny between the two strains. Another situation exists with the rfb-gene cluster that differs entirely between the two strains and encodes several glycosyltransferases possibly involved in cell wall biosynthesis and the modification of cell surface properties. This region has features of a genomic island, since the adjacent genes are conserved between the two Synechocystis strains, but the GC content drops considerably (from 48 to 35%) within this region in both strains (Fig. 2). Genomic islands consist of sets of genes that become laterally transferred, belong to the flexible gene pool of a bacterial phylum and frequently provide a certain fitness advantage.30 Accordingly, the most closely related homologues matching to these proteins are found in a wide variety of organisms. For the 50 genes located in the Synechocystis 6714 rfb gene cluster, the phylogenetically top-matching proteins belong to groups as diverse as Zetaproteobacteria, Bacilli, Clostridia, Armatimonadetes, Rhodopirellula, and Stigonematales cyanobacteria. The top-matching proteins against the Synechocystis 6803 rfb gene cluster proteins are of comparable diversity. A particular example is also the norf2 gene which was annotated on the basis of transcriptome data.19 The most closely related proteins to Norf2 (Fig. 2) are annotated in Thiocapsa marina (69% identical and 86% similar residues) and several Thioalkalivibrio species, pointing further to the alien origin of this genomic region.

Figure 2.

A likely genomic island in two Synechocystis strains. A genomic segment of ∼40 kb from Synechocystis 6803 is shown with some genes annotated for orientation (EPS, exopolysaccharide export protein; CmcI, Cephalosporin hydroxylase protein; GT1, GT1 family of glycosyltransferases; GTA-GTB, fusion protein joining a glycosyltransferase family A with a glycosyltransferase family B domain; Norf2 is a 68 amino acid peptide-encoding gene originally predicted on basis of transcriptome data indicating the presence of an mRNA for this conserved reading frame).19 Adjacent genes to this region are in the two strains of the gene pairs slr0976/slr0977 and sly1015510/sly1015500 encoding a DUF820 protein and an ABC transporter permease component; left side in 6803) and slr1084/slr1085 and sly1015040/sly1015030 (encoding a WcaF-type acyl transferase and a glycosyltransferase; right side in 6803). The GC % content, indicated by the green bars (each representing 1000 nt), drops considerably within this region. Thus, this region has features of a genomic island. The nucleotide identity to matching segments in the Synechocystis 6714 genome is colour coded (red >90%, light red >70%). The corresponding stretch in the Synechocystis 6714 genome encompasses genes sly1015490– sly1015020, almost entirely belonging to the list of unique genes in that strain (Supplementary Table S6). The proteins encoded by these genes are annotated as hypothetical proteins, UDP-glucose 4-epimerase, several different glycosyltransferases, rhamnogalacturonides degradation protein RhiN, dTDP-glucose 4′6′-dehydratase, methylase/methyltransferase, ABC transporter, GDP-mannose 4′6′dehydratase and as NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase.

An example for genome scrambling worth mentioning exists in the hydrogenase operon that encompasses the seven genes sll1220–sll1226 (hoxEFUYH plus two additional genes for proteins of unknown function) in strain 6803. In Synechocystis 6714, the orthologues of these seven genes (sly1009900–sly1009960) form a cluster with gene sly1009870 encoding the NiFe hydrogenase metallocenter assembly protein HypD, whereas the homologue in Synechocystis 6803, slr1498, is located 1.62 Mb away.

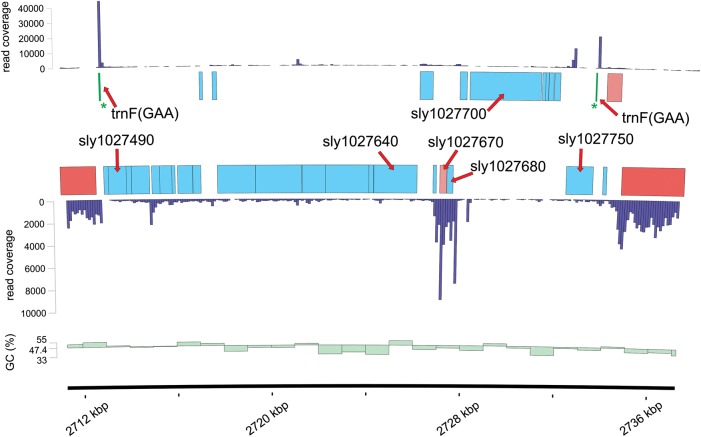

A further difference between Synechocystis 6714 and 6803 genomes is the presence of a prophage in the former but its lack in the latter (Fig. 3). As this prophage has not been previously described, we called it Psy1, for prophage in Synechocystis 1. The genomic DNA of Psy1 has integrated into the trnF (phenylalanine-specific tRNAGAA) gene, duplicating its 3′ half but restoring the gene to be functional intact. This insertion might have occurred only recently as the duplicated segment of the trnF gene is still sequence identical with the original prophage host gene. Although the Psy1 genome is with a total length of 20 660 nt quite short for a prophage, genomes of comparable size have recently been reported for siphoviruses, which infect marine cyanobacteria (e.g. S-CBS1 infecting Synechococcus strains CB0201, CB0204, CB0202, and CB0101).31 The annotation of Psy1 adds another 27 genes unique for strain 6714 (Supplementary Table S6). Most of these genes have no closely related homologues in database searches, indicating that Psy1 might belong to a novel group of bacteriophages. Clear homologues exist for Sly1027750, an integrase with several homologues in other cyanobacterial genomes; Sly1027640, an HK97 family phage portal protein with the tail sheath protein from the Pseudomonas transducing phage PhiPA3 as the best matching protein in the bacteriophage database (BlastP E-value 7e−16);32 Sly1027490, a lysozyme superfamily protein with the putative endolysin from Acinetobacter phage phiAC-1 as the best matching bacteriophage protein (BlastP E-value 2e-30);33 Sly1027700, a D5 N terminal like domain-containing protein of phage D5 proteins and bacteriophage P4 DNA primases (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Prophage Psy1 inserted into the trnFGAA gene (labelled by the green stars) of Synechocystis 6714. Genome position is drawn along the x-axis. Protein coding genes are shown in red if conserved in Synechocystis 6803 and in blue if not; trnFGAA is shown in green. Transcriptome read counts per 100 million for the forward strand are plotted above and for the reverse strand below the CDS features. The GC % content is indicated by the green bars (each representing 1000 nt). The following genes were annotated as coding for bacteriophage-related proteins and are mentioned in the text: sly1027640, HK97 family phage portal protein; sly1027490, bacteriophage lysozyme-like protein; sly1027670 and sly1027680, remotely similar to bacteriophage Cro repressor; sly1027700, D5 N terminal like domain-containing protein of phage D5 proteins and bacteriophage P4 DNA primases; sly1027750, phage integrase.

Our complementary transcriptome data (unpublished) indicate that the Psy1 genes are not significantly expressed except for a short region, encompassing the two short genes sly1027670 and sly1027680 (Fig. 3). One of the two proteins encoded by these two genes, Sly1027680, has similarity to bacteriophage repressor proteins and belongs to the HTH XRE family of Cro/CI repressor proteins, suggesting its possible involvement in silencing Psy1 activity. The other protein, Sly1027670, possesses a predicted partial endoribonuclease Y domain and revealed in database searches several good matches, with protein Ssl7074 from Synechocystis 6803 as the top hit (47% identical and 59% similar positions). Interestingly, gene ssl7074 in Synechocystis 6803 is located within the CRISPR2-associated region of cas genes next to the cas 6-2b gene, a candidate for an endonuclease involved in CRISPR crRNA maturation.14

3.3. Genetic differences with particular physiological relevance

Several of the strain-specific genes likely affect the physiology or provide certain strain-specific characteristics allowing their settlement in specific environmental niches (see Supplementary Table S5 and S6 for the list of unique genes in Synechocystis 6803 and 6714, respectively). For instance, only Synechocystis 6803 possesses genes for the proteins Flv2 and Flv4, which are essential for growth under fluctuating light and are supposed to protect photosystem II against photoinhibition.34 In contrast, in Synechocystis 6714, two operons are found, each encoding all subunits of the high-affinity K+ transporter Kdp,35 similar to the situation in filamentous cyanobacteria such as Anabaena sp. PCC7120, whereas Synechocystis 6803 harbours only one copy of the kdp2 type.36 To date, it was believed that unicellular cyanobacteria have a single kdp system or none, whereas filamentous cyanobacteria have two or more copies.36

A distinct group of protein-coding genes that differs between the two strains are associated with the CRISPR system, the prokaryotic immune system, accounting for 17 different proteins alone (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). There are three distinct loci of CRISPR-cas genes in both strains.13,14 One of them (called CRISPR3/CRISPR3*) is highly conserved, whereas the other two appear to have been substituted over their entire length, possibly by an active mechanism of exchange. Details of the different CRISPR-cas loci were published separately.13

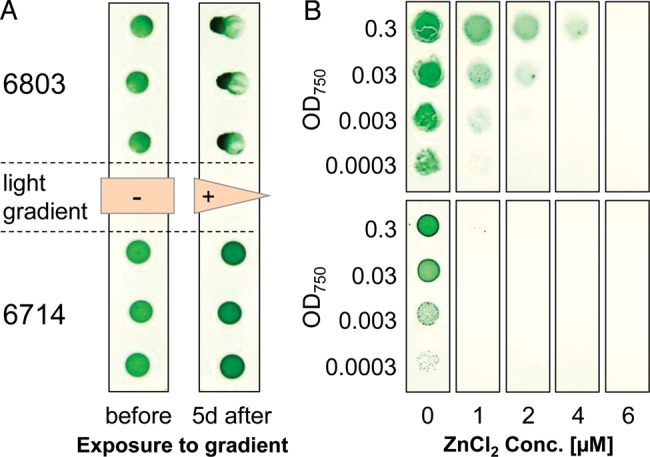

One feature that has been reported to differ even between Synechocystis 6803 substrains is motility. Therefore, a standard motility assay was conducted and demonstrated that Synechocystis 6714 is non-motile (Fig. 4). However, among the known mutations that affect motility in Synechocystis 6803 substrains, we found an intact spkA protein kinase gene,37 an intact hfq gene,38 as well as most pil genes.39 However, one missing gene in Synechocystis 6714 encodes an orthologue of PilA5 (slr1928 in Synechocystis 6803), a type 4 pilin-like protein, which is involved in the formation of thick pili and motility40 and therefore may explain the observed phenotype.

Figure 4.

Verification of physiological and genetic differences predicted upon draft genome analysis of Synechocystis 6714. (A) Phototactic motility of Synechocystis. Cells from liquid cultures (OD750 = 0.2) were dropped onto a BG11-agar plate, pre-cultivated under standard conditions for 3 days and afterwards exposed to a gradient of incident light with intensity 50 µE. The photograph was taken before and after further 5 days. (B) Drop dilution assay showing the growth on solid media in the presence of increasing concentrations of Zn2+ ions. The photograph was taken after 10 days of standard cultivation.

Furthermore, a gene cassette involved in the sensing and the resistance to Zn2+ and Co2+ (including the genes corR, corT, ziaA, and ziaR; Supplementary Table S5)41,42 appears to be specific for Synechocystis 6803 and missing in strain 6714. The functional significance of this difference was tested in growth experiments in the presence of increasing amounts of Zn2+ ions and revealed the higher tolerance of strain 6803 against high Zn2+ levels (Fig. 4).

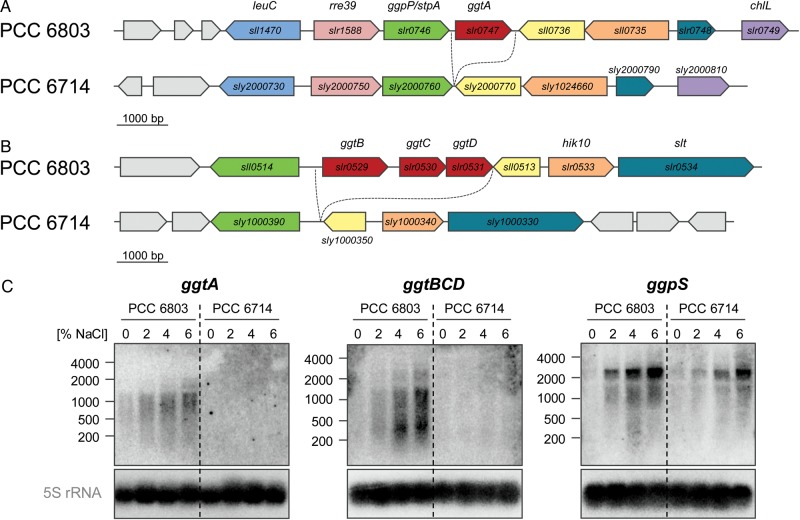

Another four genes, which were not found in the Synechocystis 6714 genome, are the ggtABCD genes encoding a transport system for the (re-)uptake of the compatible solute glucosylglycerol.43,44 Apart from that, the loci adjacent to ggtA or ggtBCD in Synechocystis 6803 are conserved in the genome of Synechocystis 6714 (Fig. 5A and B). To verify the absence of Ggt, Northern hybridization with 32P-labelled probes specific for ggtA or ggtBCD was performed with RNA from salt-treated cells. As expected, no mRNA was detected in salt-treated cells of strain 6714, whereas the expression level of the ggt genes correlated with the external salinity in Synechocystis 6803 (Fig. 5C). Moreover, the relative abundance of the mRNA for ggpS, the gene encoding the key enzyme of glucosylglycycerol synthesis, the main compatible solute in these two strains, was measured and revealed its salt-dependent expression in Synechocystis 6714 (Fig. 5C), similar to the well-characterized situation in Synechocystis 6803.45 These results further substantiated that, even though the 6714 genome is not completely finished, the lack of certain genes correlates to physiological differences.

Figure 5.

Comparative genome analysis reveals the absence of the genes encoding the glucosylglycerol transport system (Ggt). (A) Genomic region encompassing the ggtA gene in Synechocystis 6803 and of the corresponding region in Synechocystis 6714. (B) Genomic region encompassing the ggtBCD operon. Apart from Ggt, both loci are well conserved (protein identity scores of ca. 90%). (C) Occurrence of mRNAs for ggtA, ggtBCD, and ggpS in salt-treated cells of both strains. For ggpS, salt-dependent expression was observed in both strains, whereas mRNAs for ggtA and ggtBCD were not detected in strain 6714.

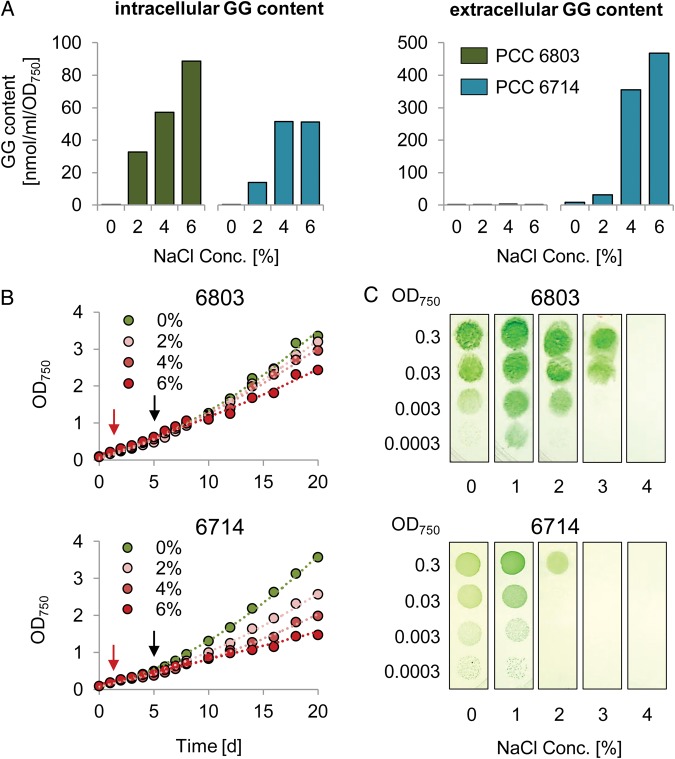

Deletion of Ggt in Synechocystis 6803 results in the inability of taking up GG as well as trehalose and sucrose.43,44 Furthermore, the ggtA mutant of strain 6803 became leaky for GG, i.e. an increase in GG in the medium was observed when cells were grown in salt medium, suggesting that its transport is mainly necessary for recovery of GG leaked through the cytoplasmic membrane into the periplasm.43 Due to the absence of Ggt in strain 6714, an uptake of GG seemed unlikely and a GG accumulation in the medium during growth at elevated salinities should be measureable. To test this hypothesis, the intra- as well as extracellular GG contents were measured for cultures acclimated to different salinities. Under freshwater conditions (0% NaCl), the cells of both strains were virtually free of GG. In Synechocystis 6803, the intracellular GG level increased corresponding to the external salt level, whereas in the surrounding medium, virtually no GG was found (Fig. 6A). In principle, a correlation of the internal GG content and the external salt concentration was also observed for strain 6714. Up to a salinity of 4% NaCl, the GG concentrations with respect to the average biomass (expressed as OD750) were similar. However, no further increase was observed when cells were grown at 6% NaCl pointing to a somewhat lower salt tolerance of strain 6714 (see below). Interestingly, GG also accumulated in high amounts in the surrounding medium, which supports the assumption that an effective system for the re-uptake of GG is missing in Synechocystis 6714 (Fig. 6A). Similar to the internal, also the external GG content increased according to the salinity (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Effects of the absence or presence of the ggtABCD system. (A) Measurement of intracellular and extracellular GG content in the two Synechocystis strains. (B) Long-term growth of Synechocystis 6803 and 6714 in liquid cultures under salt stress. Cells were pre-cultivated without salt for 2 days before salt was added to a final concentration of 2, 4, and 6% (w/v), respectively (time point is marked by a red arrow). After further 4 days, samples for RNA extraction and GG measurements were taken (marked by a black arrow). The data are representatives of two independent experiments. (C) Drop dilution assay illustrating the growth on solid media in the presence of increasing NaCl concentrations. Cell material of exponentially growing cultures was diluted to an OD750 of 0.3 and 20 µl of this suspension as well as a dilution series were dropped on NaCl-containing, agar-solidified BG11 medium. The photograph was taken after 10 days under constant illumination of 50–60 µE.

The synthesis of GG is costly regarding the consumption of energy and carbon. Thus, an effective uptake system seems reasonable for a bacterium whose osmotic adaptation is based on GG accumulation. For a Ggt mutant of Synechocystis 6803, it was postulated that the inability to take up leaked GG should result in a lower salt tolerance or at least to a lower growth performance under higher salinities, especially if the cells are grown under Ci-limitation.43 Interestingly, in liquid cultures that had a rather low surface:volume ratio, which results in a poor aeration in turn leading to a low degree of Ci availability, strain 6714 grew slower compared with strain 6803 in the presence of increased NaCl concentrations (Fig. 6B). In contrast, both strains showed similar growth performance under freshwater conditions (0% NaCl). Moreover, strain 6714 also showed a lower salt tolerance when cells were grown on solid medium in the presence of various NaCl concentrations (Fig. 6C). In the presence of 3% NaCl, no colonies were observed for strain 6714, whereas 6803 grew well under the same condition.

4. Discussion

The here presented draft genome sequence of Synechocystis 6714 allows comparative genome-based studies, as we demonstrate for several examples of physiological importance. Other comparative analyses include the direct comparison of promoter elements and of conserved sRNAs with similar regulation, implying conservation of function as we are showing in a separate manuscript.

We have noticed several important differences between the two strains. As the absence of a gene from a draft genome sequence might be considered ambiguous, we have highlighted cases for which the physiological difference predicted by the lack of certain genes could indeed be demonstrated. Among these differences is the lack of a transport system for the re-uptake of the compatible solute glucosylglycerol, linked to the observation that strain 6714 showed growth retardation at salinities above 2%, whereas strain 6803 even managed 4% in liquid cultures. The accumulation of GG in the external medium meaning a permanent loss of fixed carbon might be reasonable for the reduced salt tolerance of strain 6714 as has been postulated earlier.43

In addition to compatible solute accumulation, a balancing of the ionic composition is also important to cope with changing salinities. For instance, an active extrusion of Na+ is essential for cyanobacteria in order to maintain a low, non-toxic intracellular level. Homologues for most genes known to be involved in Na+ transport and which might be also important during salt acclimation (for review, see Hagemann)46 are found in the genome of Synechocystis 6714. However, a homologue of sll1685 (PxcA) which might be involved in the energetization of Na+ transport is missing. Furthermore, the genome of Synechocystis 6714 harbours two copies of the kdp operon each encoding a high-affinity K+ transporter (genes sly5000010–sly5000050 and sly1021590– sly1021630), whereas strain 6803 has a single copy of this operon (slr1728–slr1731). The Kdp ATPase system, initially characterized in Escherichia coli, is responsible for the immediate uptake of K+ after salt or osmotic shock in E. coli.35 In combination with glutamate as an organic counter ion, K+ is believed to act as a temporary compatible solute and moreover as a regulatory signal for the initiation of subsequent acclimation processes, also in cyanobacteria.46,47 Interestingly, the kinetics for the uptake of K+ in cyanobacteria after salt shock was characterized for Synechocystis 6714.48 A sudden osmotic shift by adding 500 mM NaCl was followed by a transient accumulation of K+ which started within the first minutes, peaked at around 30–60 min and declined after 24 h to levels similar to non-shocked cells. The decrease in K+ was accompanied by an accumulation of GG. The kinetics of a K+ uptake have not been measured so far for Synechocystis 6803, but it might be a bit different from the process in Synechocystis 6714 due to the absence of a second kdp operon.

Another interesting observation is the putative substitution of a gene cassette of ∼40 kb encoding several glycosyltransferases, transport proteins, and hypothetical proteins in the two strains. Together with the presence of some genes not found in any other cyanobacteria and the strongly reduced average GC % content in this region, this region is likely representing a genomic island. Physiologically and ecologically important genomic islands have been identified in several marine cyanobacteria.2,3,49,50 Interestingly, glycosyltransferase and glycoside hydrolase gene families have also been found frequent in several of these cyanobacterial genomic islands. Therefore, the modification of cell surface polysaccharide and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis by several of these enzymes, presumably allowing diversification of cell surface features appears central for this group of organisms. Such modification capacity is likely to be relevant in the avoidance of grazers and even more in the avoidance of bacteriophage infection.51

In conclusion, the draft genome analysis of Synechocystis 6714 allows to follow interesting research problems in this strain. However, most importantly, it opens exciting new opportunities when working with the most advanced cyanobacterial model, Synechocystis 6803.

5. Data access

The assembled scaffolds of the Synechocystis sp. PCC6714 genome are available under the accession no. AMZV01000000 at Genbank. The annotated version including also short assembled regions is available at http://www.cyanolab.de/Supplementary.html.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data are available at www.dnaresearch.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research grant ‘e:bio RNAsys’ 0316165 (to W.R.H.).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Edited by Dr Naotake Ogasawara

References

- 1.Kettler G.C., Martiny A.C., Huang K., et al. Patterns and implications of gene gain and loss in the evolution of Prochlorococcus. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scanlan D.J., Ostrowski M., Mazard S., et al. Ecological genomics of marine picocyanobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009;73:249–99. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00035-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dufresne A., Ostrowski M., Scanlan D.J., et al. Unraveling the genomic mosaic of a ubiquitous genus of marine cyanobacteria. Genome. Biol. 2008;9:R90. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-r90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaneko T., Sato S., Kotani H., et al. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions (supplement) DNA Res. 1996;3:185–209. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakao M., Okamoto S., Kohara M., et al. CyanoBase: the cyanobacteria genome database update 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D379–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aoki R., Takeda T., Omata T., Ihara K., Fujita Y. MarR-type transcriptional regulator ChlR activates expression of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis genes in response to low-oxygen conditions in cyanobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:13500–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.346205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanesaki Y., Shiwa Y., Tajima N., et al. Identification of substrain-specific mutations by massively parallel whole-genome resequencing of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 2012;19:67–79. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsr042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tajima N., Sato S., Maruyama F., et al. Genomic structure of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 strain GT-S. DNA Res. 2011;18:393–9. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trautmann D., Voss B., Wilde A., Al-Babili S., Hess W.R. Microevolution in cyanobacteria: re-sequencing a motile substrain of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 2012;19:435–48. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dss024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shih P.M., Wu D., Latifi A., et al. Improving the coverage of the cyanobacterial phylum using diversity-driven genome sequencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:1053–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217107110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanier R.Y., Kunisawa R., Mandel M., Cohen-Bazire G. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales) Bacteriol. Rev. 1971;35:171–205. doi: 10.1128/br.35.2.171-205.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rippka R., Deruelles J., Waterbury J.B., Herdmann M., Stanier R.Y. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hein S., Scholz I., Voss B., Hess W.R. Adaptation and modification of three CRISPR loci in two closely related cyanobacteria. RNA Biol. 2013;10:852–64. doi: 10.4161/rna.24160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scholz I., Lange S.J., Hein S., Hess W.R., Backofen R. CRISPR-Cas systems in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 exhibit distinct processing pathways involving three Cas6 and a Cmr2 protein. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joset F. Transformation in Synechocystis PCC 6714 and 6803: preparation of chromosomal DNA. Methods. Enzymol. 1988;167:712–4. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marraccini P., Bulteau S., Cassier-Chauvat C., Mermet-Bouvier P., Chauvat F. A conjugative plasmid vector for promoter analysis in several cyanobacteria of the genera Synechococcus and Synechocystis. Plant Mol. Biol. 1993;23:905–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00021546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zerbino D.R., Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aziz R.K., Bartels D., Best A.A., et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitschke J., Georg J., Scholz I., et al. An experimentally anchored map of transcriptional start sites in the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:2124–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015154108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enright A.J., Van Dongen S., Ouzounis C.A. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1575–84. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siguier P., Varani A., Perochon J., Chandler M. Exploring bacterial insertion sequences with ISfinder: objectives, uses, and future developments. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;859:91–103. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-603-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinto F.L., Thapper A., Sontheim W., Lindblad P. Analysis of current and alternative phenol based RNA extraction methodologies for cyanobacteria. BMC Mol. Biol. 2009;10:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagemann M., Ribbeck-Busch K., Klahn S., Hasse D., Steinbruch R., Berg G. The plant-associated bacterium Stenotrophomonas rhizophila expresses a new enzyme for the synthesis of the compatible solute glucosylglycerol. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:5898–906. doi: 10.1128/JB.00643-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steglich C., Futschik M.E., Lindell D., Voss B., Chisholm S.W., Hess W.R. The challenge of regulation in a minimal photoautotroph: non-coding RNAs in Prochlorococcus. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaneko T., Nakamura Y., Sasamoto S., et al. Structural analysis of four large plasmids harboring in a unicellular cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 2003;10:221–8. doi: 10.1093/dnares/10.5.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu W., McFadden B.A. Sequence analysis of plasmid pCC5.2 from cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803 that replicates by a rolling circle mechanism. Plasmid. 1997;37:95–104. doi: 10.1006/plas.1997.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang X., McFadden B.A. A small plasmid, pCA2.4, from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 encodes a rep protein and replicates by a rolling circle mechanism. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:3981–91. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.3981-3991.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang X., McFadden B.A. The complete DNA sequence and replication analysis of the plasmid pCB2.4 from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Plasmid. 1994;31:131–7. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okamoto S., Ikeuchi M., Ohmori M. Experimental analysis of recently transposed insertion sequences in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 1999;6:265–73. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.5.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hacker J., Carniel E. Ecological fitness, genomic islands and bacterial pathogenicity. A Darwinian view of the evolution of microbes. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:376–81. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang S., Wang K., Jiao N., Chen F. Genome sequences of siphoviruses infecting marine Synechococcus unveil a diverse cyanophage group and extensive phage-host genetic exchanges. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;14:540–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monson R., Foulds I., Foweraker J., Welch M., Salmond G.P. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa generalized transducing phage phiPA3 is a new member of the phiKZ-like group of ‘jumbo’ phages, and infects model laboratory strains and clinical isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Microbiology. 2011;157:859–67. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.044701-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J.H., Oh C., Choresca C.H., et al. Complete genome sequence of bacteriophage phiAC-1 infecting Acinetobacter soli strain KZ-1. J. Virol. 2012;86:13131–32. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02454-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allahverdiyeva Y., Mustila H., Ermakova M., et al. Flavodiiron proteins Flv1 and Flv3 enable cyanobacterial growth and photosynthesis under fluctuating light. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:4111–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221194110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood J.M. Osmosensing by bacteria: signals and membrane-based sensors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:230–62. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.230-262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ballal A., Basu B., Apte S.K. The Kdp-ATPase system and its regulation. J. Biosci. 2007;32:559–68. doi: 10.1007/s12038-007-0055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panichkin V.B., Arakawa-Kobayashi S., Kanaseki T., et al. Serine/threonine protein kinase SpkA in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 is a regulator of expression of three putative pilA operons, formation of thick pili, and cell motility. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:7696–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.00838-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dienst D., Dühring U., Mollenkopf H., et al. The RNA chaperone Hfq is essential for cell motility of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Microbiology. 2008;154:3134–43. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/020222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshihara S., Geng X., Ikeuchi M. pilG Gene cluster and split pilL genes involved in pilus biogenesis, motility and genetic transformation in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:513–21. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhaya D., Bianco N.R., Bryant D., Grossman A. Type IV pilus biogenesis and motility in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;37:941–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia-Dominguez M., Lopez-Maury L., Florencio F.J., Reyes J.C. A gene cluster involved in metal homeostasis in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:1507–14. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1507-1514.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thelwell C., Robinson N.J., Turner-Cavet J.S. An SmtB-like repressor from Synechocystis PCC 6803 regulates a zinc exporter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:10728–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hagemann M., Richter S., Mikkat S. The ggtA gene encodes a subunit of the transport system for the osmoprotective compound glucosylglycerol in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:714–20. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.714-720.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mikkat S., Hagemann M. Molecular analysis of the ggtBCD gene cluster of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 encoding subunits of an ABC transporter for osmoprotective compounds. Arch. Microbiol. 2000;174:273–82. doi: 10.1007/s002030000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marin K., Huckauf J., Fulda S., Hagemann M. Salt-dependent expression of glucosylglycerol-phosphate synthase, involved in osmolyte synthesis in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:2870–7. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.2870-2877.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hagemann M. Molecular biology of cyanobacterial salt acclimation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011;35:87–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gralla J.D., Vargas D.R. Potassium glutamate as a transcriptional inhibitor during bacterial osmoregulation. EMBO J. 2006;25:1515–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reed R.H., Warr S.R.C., Richardson D.L., Moore D.J., Stewart W.D.P. Multiphasic osmotic adjustment in a euryhaline cyanobacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1985;28:225–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coleman M.L., Chisholm S.W. Code and context: Prochlorococcus as a model for cross-scale biology. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stuart R.K., Brahamsha B., Busby K., Palenik B. Genomic island genes in a coastal marine Synechococcus strain confer enhanced tolerance to copper and oxidative stress. ISME J. 2013;7:1139–49. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Avrani S., Wurtzel O., Sharon I., Sorek R., Lindell D. Genomic island variability facilitates Prochlorococcus-virus coexistence. Nature. 2011;474:604–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.