Abstract

Statistical challenges arise from modern biomedical studies that produce time course genomic data with ultrahigh dimensions. In a renal cancer study that motivated this paper, the pharmacokinetic measures of a tumor suppressor (CCI-779) and expression levels of 12625 genes were measured for each of 33 patients at 8 and 16 weeks after the start of treatments, with the goal of identifying predictive gene transcripts and the interactions with time in peripheral blood mononuclear cells for pharmacokinetics over the time course. The resulting dataset defies analysis even with regularized regression. Although some remedies have been proposed for both linear and generalized linear models, there are virtually no solutions in the time course setting. As such, a novel GEE-based screening procedure is proposed, which only pertains to the specifications of the first two marginal moments and a working correlation structure. Different from existing methods that either fit separate marginal models or compute pairwise correlation measures, the new procedure merely involves making a single evaluation of estimating functions and thus is extremely computationally efficient. The new method is robust against the mis-specification of correlation structures and enjoys theoretical readiness, which is further verified via Monte Carlo simulations. The procedure is applied to analyze the aforementioned renal cancer study and identify gene transcripts and possible time-interactions that are relevant to CCI-779 metabolism in peripheral blood.

Keywords: Correlated data, Generalized estimating equations, Longitudinal analysis, Sure screening property, Time course data, Ultrahigh dimensionality, Variable selection

1 Introduction

An urgent need has emerged in biomedical studies for statistical procedures capable of analyzing and interpreting ultrahigh dimensional time course data. Consider a motivating renal cancer study, wherein the pharmacokinetics of a tumor suppressor (CCI-779) and expression levels of 12625 genes were measured for each of 33 patients at 8 and 16 weeks after the start of treatments. The number of measurements for each patient varies from 1 to 4 as some patients missed their appointments due to administrative reasons. The goal of the study was to identify gene transcripts that predict the pharmacokinetic measures over the time course and identify possible time-interactions, reflecting how time modifies the regulation of relevant genes on the CCI-779 metabolism. However, the resulting dataset defies analysis even with regularized regression.

When the number of the covariates greatly exceeds the number of subjects, traditional variable selection methods incur difficulties in speed, stability, and accuracy (Fan and Lv, 2008). Sure independence screening has emerged as a powerful means to effectively eliminate unimportant covariates, allowing the much fewer “survived” covariates to be fed into more sophisticated regularization techniques. Applications have been found in the context of linear regressions with Gaussian covariates and independent responses (Fan and Lv, 2008), generalized linear models (Fan et al., 2009; Fan and Song, 2010), additive models (Fan et al., 2011), single index models (Zhu et al., 2011), Cox models (Zhao and Li, 2012a), nonparametric regression models (Lin et al., 2013). Nonetheless, most of the methods are derived for independent outcome data and may not be effective for time course data as they typically ignore within-subject correlations among outcomes. Recently, Li et al. (2012) proposed to use a distance screening measure for correlated responses, but their method is confined to a balanced configuration and may not be applicable when subjects have varying numbers of observations.

On the other side of the spectrum, a variety of variable selection methods have been proposed to handle correlated outcome data with high-dimensional covariates. These methods have included, for example, bridge-, LASSO- and SCAD-penalized generalized estimating equations (GEE) (Fu, 2003; Wang et al., 2012), penalized joint log likelihoods for mixed-effects models with continuous responses (Bondell et al., 2010), and a two-stage shrinkage approach (Xu et al., 2013). However, they all stipulate that the number of covariates p grows to infinity at a polynomial rate o(nα) for some 0 ≤ α < 4/3. They can hardly handle ultrahigh dimensional cases because of challenges in computation, statistical accuracy, and numerical stability (Fan et al., 2009).

Responding to these statistical challenges, we propose a new GEE-based screening procedure (GEES, hereafter) for ultrahigh dimensional time course data. This would be the first attempt to handle both balanced and unbalanced ultrahigh dimensional time course data in the presence of within-subject correlations. Similar to the GEE approach (Liang and Zeger, 1986), the proposed procedure pertains only to the specification of the first two marginal moments and a working correlation structure. Hence, it enjoys the desirable robustness inherited from the parental GEE approach. Specifically, with p growing at an exponential rate of n, the proposed procedure possesses the sure screening property with a vanishing false selection rate even when the working correlation structure is misspecified. Computationally, GEES significantly advances existing screening procedures by evaluating an ultrahigh dimensional GEE function only once instead of fitting p separate marginal models. This is an important feature of GEES to make the method worthwhile to advocate. Aside from the computational effectiveness, we also note that the method differs from the EEScreen method proposed by Zhao and Li (2012b) in that our estimating functions are not confined to be U-statistics, a key assumption stipulated in that work.

Further, parallel to the ISIS procedure in Fan and Lv (2008), we suggest an iterative version of GEES (IGEES) to handle difficult cases when the response and some important covariates are marginally uncorrelated. We improve the original algorithm by, instead of computing the correlation between the residuals of the response against the remaining covariates, computing the correlation between the original response variable and the projection of the remaining covariates onto the orthogonal complement space of the selected covariates. This way, the correlation structure among covariates is retained. Our Monte Carlo simulations manifest the drastically improved performance of IGEES under some challenging settings.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce the GEES for covariate screening in a broader context of longitudinal data analysis. Section 3 presents the corresponding theoretical properties. In Section 4, we investigate the finite sample performance of the GEES by Monte Carlo simulations and an application to the advanced renal cancer data set. Section 5 contains an iterative version of GEES that is used to identify some relevant gene-by-time interactions that regularizes the CCI-779 metabolism in our motivating data example. The paper is concluded with a short discussion in Section 6 and all the technical proofs are relegated to the Appendix.

2 GEE based sure screening

2.1 Generalized estimating equations

In a longitudinal study (including time course genomic studies as a special case), suppose a response Yik and a p-dimensional vector of covariates Xik (e.g. gene expressions) are observed at the kth time point for the ith subject, i = 1, …, n and k = 1, …,mi. Let Yi = (Yi1, …, Yimi)τ be the vector of responses for the ith subject, and Xi = (Xi1, …, Ximi)τ be the corresponding mi × p matrix of the covariates. Assume the conditional mean of Yik given Xik is

| (2.1) |

where g is a known link function, and β is a p-dimensional unknown parameter vector. Let be the conditional variance of Yik given Xik, Ai(β) be an mi × mi diagonal matrix with kth diagonal element , and Ri(α) be an mi × mi working correlation matrix, where α is a finite dimensional parameter vector which can be estimated by residual-based moment method. The GEE estimator of β is defined to be the solution of

| (2.2) |

where μi(β) = (μi1(β), …, μimi(β))τ, μ̇i(β) = ∂μi(β)/∂β is an mi × p matrix, and is the working covariance matrix of Yi.

As in Liang and Zeger (1986), we assume that Yik belongs to an exponential family with a canonical link function in (2.1), implying that the first two moments of Yik can be written as and , for some differentiable function a(·). For simplicity, we assume that mi = m < ∞ and ϕ = 1 throughout this article, though our procedure is still valid for non-canonical response with varying cluster sizes. Then, equation (2.2) can be reduced to

| (2.3) |

where Ri(α) = R(α) for i = 1, …, n when mi ≡ m. We stress that the assumption of Ri(α) = R(α) is for the ease of presentation (in the next section) and is non-essential. A key advantage of the GEE approach is that, when p is of order o(n1/3), it yields a consistent estimator even with mis-specified working correlation structures (Wang, 2011). But it fails when the dimensionality p greatly exceeds the number of subjects n, even if regularized methods are used (Wang et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2013). This brings up a high demand of screening methods that can quickly reduce p.

2.2 A new screening procedure

To simplify the presentation, we assume (Yi, Xi) are iid copies of (Y, X), where Y is the multivariate response and X = (x1, …, xp) is the corresponding m × p covariate matrix. Then, let μ(β) be the mean vector of Y, A(β) be an m × m diagonal matrix with the variances of Y given X as the diagonal elements, and R(α) an m × m correlation matrix. Without loss of generality, we assume throughout this article that the covariates are standardized to have mean zero and standard deviation one, though our procedure is still valid for non-standardized covariates. Let β0 be the true value of β, g(β) = E{XτA1/2(β)R−1(α)A−1/2(β)(Y − μ(β)}, Ω0 = A1/2(0)R−1(α)A−1/2(0), and gj(0) be the jth element of g(0). Define the trace of a symmetric matrix M as tr(M), and the covariance matrix of two random vectors a and b as Cov(a, b). It follows that

where the last equality holds as xj is a mean 0 vector and the expectation is taken with respect to the joint distribution of (Y, xj). This implies that gj(0) is a surrogate measure of the dependence between the response vector Y and the jth covariate vector xj, justifying the utility of gj(0) as a thresholding criterion for covariate screening.

Based on {(Yi, Xi), i = 1, …, n}, an empirical estimate of g(β) would be

Interestingly, it coincides with G(β) as defined in (2.3), based on which we carry out the screening procedure. Specifically, let Gj(0), the estimate of gj(0), be the jth element of G(0). We select covariates with large values of Gj(0). As R(α) is unknown a priori, we replace G(0) by Ĝ(0) with R(α) replaced by the empirical estimate R(α̂), where α̂ is obtained via the residual-based moment method. Let R̂ = R(α̂). Then, Ĝ(0) is defined as

| (2.4) |

Hence, we would select the submodel using

| (2.5) |

where γn is a predefined thresholding value. Under some regularity conditions, such a procedure, termed as the GEE-based sure screening (GEES), would effectively reduce the full model of size p down to a submodel ℳ̂γn with size less than n.

Remark 1. The proposed procedure (2.5) only requires a single evaluation of the GEE function G(β) at β = 0 instead of p separate GEE models, rendering much computational convenience.

Remark 2. Consider the following independent linear model:

where εi are independent identically distributed from the standard normal distribution N(0, 1). The GEE function reduces to

Therefore, for any given γn, the GEES select the submodel

where y = (Y1, …, Yn)τ and X·j is the jth column of the n × p data matrix X = (X1, …, Xn)τ. Thus our procedure includes the original sure independent screening proposed by Fan and Lv (2008) as a special case.

3 Sure screening properties of GEES

We study the sure screening properties of the proposal. Let p = pn be a function of the sample size n, β0 be the true value of pn-dimensional coefficients β and ℳ0 = {1 ≤ j ≤ pn: β0 ≠ 0} be the true model with model size sn = |ℳ0|. For a symmetric matrix A, we write λmin(A) and λmax(A) for the minimum and maximum eigenvalues, respectively. Define ‖A‖F = tr1/2(AτA) as its Frobenius norm and ‖a‖2 as the L2 norm of a vector a. Let R̂ be the estimated working correlation matrix and .

We assume the following regularity conditions:

-

(C1)

β0 is an interior point of a compact set 𝒞.

-

(C2)

, where R̄ is a constant positive definite matrix. The common true correlation matrix R0 satisfies 0 < λmin(R0) ≤ λmax(R0) < ∞.

-

(C3)

For each 1 ≤ i ≤ n and 1 ≤ k ≤ m, Xik is uniformly bounded by a positive constant c1.

-

(C4)

There exists a finite positive constant c2 such that for some δ > 0 and every β ∈ 𝒞.

-

(C5)There exists a finite constant c3 > 0 and a positive definite matrix R̄ such that minj∈ℳ0 |ḡj(0)| ≥ c3n−κ for some 0 < κ < 1/2, where ḡj(0) is the jth element of

-

(C6)

sn = op(n1/3−2κ/3) and log pn = o(n1−2κ), where κ is given in (C5).

-

(C7)

Let . Assume that ‖Σβ0‖2 = Op(1). Further, let , where Δ is a constant. On ℬ, are uniformly bounded away from 0 and ∞, and are uniformly bounded by a finite positive constant c4 for 1 ≤ i ≤ n, 1 ≤ k ≤ m.

Conditions (C1) and (C2) are analogous to conditions (A1), (A4) of Wang et al. (2012) for generalized estimating equations. Condition (C3) has been assumed in Wang et al. (2012), Zhu et al. (2011), and Li et al. (2012). This condition could be relaxed by the following moment condition: For each 1 ≤ i ≤ n and 1 ≤ k ≤ m, there exists a positive constant t0 such that

for all 0 < t < t0. But, in practice, centralized and normalized covariates will trivially satisfy (C3), which empirically justifies its usage. Condition (C4) is similar to the condition in Lemma 2 of Xie and Yang (2003), condition (Ñδ) in Balan and Schiopu-Kratina (2005), and condition (A5) in Wang (2011), which usually holds for outcome Yi of a variety of types, including binary, Poisson and Gaussian. With ḡj(0) = tr{A1/2(0)R̄−1A−1/2(0) Cov(μ(β0), xj)}, condition (C5) is similar to the condition in Theorem 3 of Fan and Song (2010), ensuring the marginal signals are stronger than the stochastic noise as shown in Web Appendix A. The first part of condition (C7) is analogous to condition F in Fan and Song (2010). The second part of condition (C7) is analogous to condition (A6) of Wang et al. (2012), which is generally satisfied for the GEE.

The following theorem establishes the sure screening property for the GEES procedure. The proofs are relegated to the Appendix.

Theorem 1. Under conditions (C1) – (C7), if γn = c3n−κ/4, then there exists a positive constant c depending on c1 and c2 such that

Remark 3. It is not uncommon to misspecify the working correlation structure R̂ involved in (2.4) for Ĝ(0). However, Theorem 1 guarantees that, with a probability tending to one, all of the important covariates will be retained by the GEES procedure even if the working correlation structure is misspecified (see condition (C2)).

Remark 4. Similar to existing screening procedures, from Theorem 1, we find that only the size of non-sparse elements sn matters for the purpose of screening, not the dimensionality pn.

Theorem 2. Under conditions (C1) – (C7), if γn = c3n−κ/4, then there exists a positive constant c, depending on c2, cβ and boundaries c1 and c4, such that

Theorem 2 states that the size of ℳ̄γn can be controlled by the GEES procedure and is of particular importance in the longitudinal setting. First, the probability that the bound holds approaches to one even if log pn = o(n1−2κ) with 0 < κ < 1/2. This implies that the size of false positives can be controlled with high probability even in the longitudinal setting with ultrahigh dimensional covariates. Second, this bound holds with high probability even with misspecified working correlation structures.

4 Numerical studies

We first assess the finite sample performance of the GEES via Monte Carlo simulations. Then, we further illustrate the proposed procedure with an analysis of advanced renal cancer data of Boni et al. (2005).

4.1 Simulation results

Throughout, we consider three types of working correlation structures for the multivariate outcomes: independence, exchangeable and AR(1), and label the corresponding approaches as GEES_IND, GEES_CS, and GEES_AR1, respectively. To mimic the real situations, we set the total number of covariates p = 1000, 6000, 20000 and repeat our procedure 400 times for each configuration.

To assess the sure screening property, we record the minimum model size (MMS) required to contain the true model ℳ0. We report the 5%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 95% quantiles of MMS. For the assessment of computational efficiency, we also report the average computing time in seconds for each method.

Example 1 To mimic the real data example below, we generate the correlated normal responses from the model

where i = 1, …, 30, k = 1, …, 10, Xik = (Xik1, …, Xikp)τ is a p-dimensional covariate vector and β = (1, 0.8, 0.5,−0.7, 0, …, 0)τ. For the covariates, Xik1 is independently from the Bernoulli(0.5) distribution, and Xik2 to Xikp are independently from the multivariate normal distribution with mean 0 and an AR(1) covariance matrix with marginal variance 1 and autocorrelation coefficient 0.8. The random errors (εi1, …, εi10)τ are independently from the multivariate normal distribution with marginal mean 0, marginal variance 1 and an exchangeable correlation with parameter ρ. Two values of ρ are considered: ρ = 0.5 and 0.8. And to control the signal to noise ratio (SNR), we vary the constant c in front to . We consider c = 0.5, 0.75, and 1.5, which corresponds to SNR = 30%, 50%, and 80%, respectively.

As a comparison, we also implement the sure independence screening (SIS) proposed by Fan and Lv (2008) and the distance correlation based SIS (DC-SIS) proposed by Li et al. (2012). Tables 1, 2 and 3 reports the 5%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 95% percentiles of the minimum model size (MMS) and the average computing time by different screening methods under different SNR settings. We see that our method performs well across a wide range of signal to noise ratios. In particular, under the correctly specified correlation structure (CS), the GEES_CS gives the smallest MMS to ensure the inclusion of all truly active covariates. It significantly outperforms other methods, especially in the higher dimensional case with strong within-subject associations. In contrast, the DC-SIS performs relatively poor when the signal to noise ratio is small, though it accounts for the within-subject correlations as well. And the last column reveals that the GEES is extremely more efficient than the DC-SIS in computation. On the other hand, the GEES_IND and the SIS perform same in linear models, which is in accordance with Remark 2 in Section 2.2.

Table 1.

The 5%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 95% percentiles of the minimum model size and the average runtime in seconds (standard deviation) in Example 1 (with Xeon X5670 2.93 GHz CPU) when SNR = 30%

| p | ρ | Method | 5% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 95% | TIME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 5 | 25 | 121 | 372.75 | 837.50 | 0.05(0.01) |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 11.75 | 50.50 | 193.25 | 715.10 | 0.12(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 5 | 25 | 90.50 | 361.75 | 829.10 | 0.14(0.01) | ||

| SIS | 5 | 25 | 121 | 372.75 | 837.50 | 0.05(0.01) | ||

| DC-SIS | 49 | 406.75 | 598 | 781 | 915.20 | 1.16(0.04) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 5 | 24 | 94.50 | 307 | 781.25 | 0.04(0.01) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 5 | 12 | 45.25 | 305.50 | 0.10(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 8 | 29 | 122 | 495.25 | 0.12(0.01) | ||

| SIS | 5 | 24 | 94.50 | 307 | 781.25 | 0.04(0.01) | ||

| DC-SIS | 200.85 | 422 | 613 | 795 | 961 | 1.14(0.03) | ||

| 6000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 10 | 111.25 | 474 | 1805.25 | 4774.90 | 0.30(0.02) |

| GEES_CS | 5 | 32.75 | 250.50 | 1009.75 | 4030.25 | 0.36(0.02) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 11 | 115 | 547 | 2174.25 | 5035.20 | 0.37(0.03) | ||

| SIS | 10 | 111.25 | 474 | 1805.25 | 4774.90 | 0.30(0.02) | ||

| DC-SIS | 1133.80 | 2531.25 | 3634.50 | 4697 | 5631.25 | 6.98(0.01) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 11 | 102.75 | 552 | 1942 | 4734.50 | 0.28(0.04) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 9 | 62.50 | 337.25 | 2608.50 | 0.35(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 32 | 215 | 924.25 | 3997.90 | 0.37(0.02) | ||

| SIS | 11 | 102.75 | 552 | 1942 | 4734.50 | 0.28(0.04) | ||

| DC-SIS | 919.85 | 2393 | 3634.50 | 4748.75 | 5596.20 | 6.89(0.09) | ||

| 20000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 35.90 | 433 | 2005.50 | 6779.75 | 16333.35 | 1.22(0.03) |

| GEES_CS | 8.95 | 156.75 | 871.50 | 3874 | 14848.30 | 1.27(0.04) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 23.95 | 362.50 | 1892.50 | 6725.25 | 16322.90 | 1.37(0.06) | ||

| SIS | 35.90 | 433 | 2005.50 | 6779.75 | 16333.35 | 1.22(0.03) | ||

| DC-SIS | 3147.85 | 7841.25 | 12233.50 | 15680.50 | 19001.45 | 23.19(0.17) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 51.95 | 494.75 | 2185 | 6473.25 | 16595 | 1.26(0.06) | |

| GEES_CS | 5 | 30.75 | 171.50 | 1142.25 | 6211.60 | 1.33(0.04) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 9.95 | 124 | 696.50 | 2492.50 | 10067 | 1.35(0.04) | ||

| SIS | 51.95 | 494.75 | 2185 | 6473.25 | 16595 | 1.26(0.06) | ||

| DC-SIS | 3585.45 | 8486 | 12464 | 16071.75 | 19301.15 | 23.12(0.14) |

Table 2.

The 5%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 95% percentiles of the minimum model size and the average runtime in seconds (standard deviation) in Example 1 (with Xeon X5670 2.93 GHz CPU) when SNR = 50%

| p | ρ | Method | 5% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 95% | TIME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 4 | 8 | 32 | 131.25 | 577.45 | 0.04(0.01) |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 6 | 15 | 65 | 363.60 | 0.11(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 10 | 37.50 | 123 | 616.80 | 0.12(0.01) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 8 | 32 | 131.25 | 577.45 | 0.04(0.01) | ||

| DC-SIS | 89.80 | 258.75 | 484.50 | 697.50 | 928.05 | 1.12(0.01) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 4 | 8 | 26.50 | 99 | 578.15 | 0.03(0.01) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 120.10 | 0.10(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 5 | 19 | 63 | 309.60 | 0.13(0.01) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 8 | 26.50 | 99 | 578.15 | 0.03(0.01) | ||

| DC-SIS | 95.95 | 291 | 480 | 678.75 | 931.10 | 1.13(0.03) | ||

| 6000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 5 | 27 | 162 | 856.75 | 3401.90 | 0.30(0.02) |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 11 | 64.50 | 377 | 2195.15 | 0.34(0.02) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 5 | 33.75 | 198.50 | 812 | 3762.25 | 0.36(0.02) | ||

| SIS | 5 | 27 | 162 | 856.75 | 3401.90 | 0.30(0.02) | ||

| DC-SIS | 523.60 | 1735.75 | 2934 | 4187 | 5575.60 | 7.04(0.10) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 4 | 16.75 | 106 | 602.25 | 2764.30 | 0.32(0.02) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 5 | 17 | 88.25 | 728.20 | 0.33(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 10 | 71 | 323.50 | 1854.25 | 0.36(0.02) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 16.75 | 106 | 602.25 | 2764.30 | 0.32(0.02) | ||

| DC-SIS | 582.10 | 1676.25 | 2889.50 | 4029.50 | 5579.95 | 6.88(0.06) | ||

| 20000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 8.95 | 90.25 | 474.50 | 2451.75 | 9952 | 1.24(0.03) |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 34 | 254.50 | 1228 | 5770.70 | 1.30(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 8 | 138 | 67.507 | 2497.25 | 11559.60 | 1.36(0.01) | ||

| SIS | 8.95 | 90.25 | 474.50 | 2451.75 | 9952 | 1.24(0.03) | ||

| DC-SIS | 1990.65 | 6228.25 | 10783 | 14770.50 | 18772.55 | 23.55(0.28) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 6 | 54.25 | 363.50 | 1910.25 | 9866 | 1.27(0.03) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 8 | 42 | 289 | 2927.10 | 1.27(0.04) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 35 | 216 | 1027.50 | 7477.95 | 1.34(0.02) | ||

| SIS | 6 | 54.25 | 363.50 | 1910.25 | 9866 | 1.27(0.03) | ||

| DC-SIS | 2198.45 | 5859.25 | 10268.50 | 14201.50 | 18631.05 | 23.29(0.32) |

Table 3.

The 5%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 95% percentiles of the minimum model size and the average runtime in seconds (standard deviation) in Example 1 (with Xeon X5670 2.93 GHz CPU) when SNR = 80%

| p | ρ | Method | 5% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 95% | TIME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 4 | 4 | 6 | 17.25 | 174.05 | 0.04(0.01) |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 6 | 18 | 167.25 | 0.11(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 5 | 11.50 | 52.75 | 464.20 | 0.13(0.01) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 4 | 6 | 17.25 | 174.05 | 0.04(0.01) | ||

| DC-SIS | 30.80 | 136.75 | 300.50 | 559.50 | 883.10 | 1.12(0.04) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 4 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 109.65 | 0.04(0.01) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 68.05 | 0.10(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 38 | 222.40 | 0.12(0.01) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 109.65 | 0.04(0.01) | ||

| DC-SIS | 30.95 | 123.75 | 301 | 571 | 859.10 | 1.16(0.02) | ||

| 6000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 4 | 5 | 15 | 97.25 | 924.40 | 0.28(0.02) |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 14 | 80.25 | 619.45 | 0.37(0.02) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 10 | 49.50 | 294.25 | 1762.10 | 0.39(0.02) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 5 | 15 | 97.25 | 924.40 | 0.28(0.02) | ||

| DC-SIS | 156.75 | 812.25 | 1910 | 3505.75 | 5408.40 | 6.86(0.11) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 4 | 5 | 16 | 92.75 | 1231.55 | 0.30(0.02) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 8 | 39 | 491.50 | 0.36(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 8 | 34 | 187.50 | 1206.95 | 0.38(0.02) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 5 | 16 | 92.75 | 1231.55 | 0.30(0.02) | ||

| DC-SIS | 118.85 | 734.25 | 1792 | 3355 | 5205.50 | 6.92(0.04) | ||

| 20000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 4 | 9 | 41.50 | 301.50 | 2862.10 | 1.16(0.01) |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 7.75 | 35.50 | 186.50 | 1926.55 | 1.31(0.05) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 5 | 29 | 139 | 704.50 | 5524.50 | 1.30(0.02) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 9 | 41.50 | 301.50 | 2862.10 | 1.16(0.01) | ||

| DC-SIS | 343.45 | 2168 | 5653 | 10816.25 | 17624.50 | 23.11(0.16) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 4 | 6 | 32.50 | 298.75 | 2996.25 | 1.13(0.02) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 5 | 18 | 126.25 | 1850.45 | 1.36(0.03) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 13 | 106 | 780.50 | 4502.45 | 1.32(0.05) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 6 | 32.50 | 298.75 | 2996.25 | 1.13(0.02) | ||

| DC-SIS | 646.35 | 2974.50 | 6248 | 11632.50 | 17498.30 | 25.54(0.12) |

Example 2 Consider a balanced Poisson regression model:

where i = 1, …, 400, k = 1, …, 10, λ(u) = exp(u), β = (1.5 − U1, …, 1.5 − U4, 0, …, 0)τ, and Uk’s follow a uniform distribution U[0,1], reflecting different strengths of signals. For the p-dimensional covariate vectors, we generate Xik independently from the multivariate normal distribution with mean 0 and an AR(1) covariance matrix with marginal variance 1 and autocorrelation coefficient 0.8. The response vector for each cluster has an exchangeable correlation structure with correlation coefficient ρ. We consider ρ = 0.5 and 0.8 to represent moderate and strong within-cluster correlations.

Similar to Example 1, we also implement the SIS proposed by Fan and Song (2010) and the DC-SIS proposed by Li et al. (2012) for comparison. Table 4 summarizes the minimum model size and the average computing time by different screening methods. In the presence of correlation, the proposed GEES outperforms the competing methods even when the working correlation structure is misspecified. The DC-SIS performs well in this case where nonzero coefficients have large values, but as in Example 1, it incurs much more computational burden than the GEES. On the other hand, the GEES IND outperforms the SIS significantly in computation, as the latter needs to fit p marginal Poisson regressions, which is relatively unstable under this dependent features setting, whereas the former only needs a single evaluation of the estimating function. Moreover, as the number of covariates p increases, the GEES performs very stably as opposed to the SIS.

Table 4.

The 5%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 95% percentiles of the minimum model size and the average computing time in seconds (standard deviation) in Example 2 (with Xeon X5670 2.93 GHz CPU)

| p | ρ | Method | 5% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 95% | TIME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 0.82(0.06) |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1.64(0.10) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 2.08(0.15) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 6 | 47 | 180 | 410.30 | 132.91(32.39) | ||

| DC-SIS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 130.78(1.03) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 0.80(0.01) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1.61(0.02) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 2.06(0.13) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 5 | 34 | 149.25 | 515.50 | 134.59(40.08) | ||

| DC-SIS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5.05 | 130.67(1.07) | ||

| 6000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1.61(0.04) |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1.96(0.01) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 2.30(0.01) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 6 | 119 | 762.50 | 2062 | 305.08(45.05) | ||

| DC-SIS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7.05 | 199.50(0.41) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1.62(0.02) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 2.00(0.03) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 2.29(0.04) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 6 | 103.50 | 783.75 | 2821.85 | 298.57(44.77) | ||

| DC-SIS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8.15 | 197.11(0.06) | ||

| 20000 | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 8.29(0.69) |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 8.65(0.72) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6.05 | 8.63(0.54) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 6 | 350.50 | 2161.50 | 5675.70 | 671.68(95.53) | ||

| DC-SIS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 715.27(49.56) | ||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 8.30(0.49) | |

| GEES_CS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 8.91(0.65) | ||

| GEES_AR1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8.10 | 8.78(0.84) | ||

| SIS | 4 | 6 | 307 | 2017.75 | 7129.35 | 651.14(93.48) | ||

| DC-SIS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 10.05 | 706.47(48.92) | ||

4.2 Advanced renal cancer data analysis

We apply the proposed screening method to study a phase II trial of CCI-779, an anti-cancer inhibitor, administered in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (Boni et al., 2005).

Pharmacokinetic profiling (i.e. the cumulative concentration of CCI-779 measured by the area under the curve) for a total of 33 patients was performed at 8 and 16 weeks after the start of treatments. The 8 week was chosen as metabolism of CCI-779 would be stabilized by then and its measurement could be regarded as the baseline. However, a sizable portion of patients missed their measurements at 8-week or 16-week because of administrative issues while some patients were measured twice at 8 or 16 weeks, which resulted in an unbalanced data structure. A total of expression values for 12625 probesets were also measured for each subject at each time point using HgU95A Affymetrix microarrays during the course of therapy. One goal of the trial was to identify transcripts in peripheral blood mononuclear cells that, after the initiation of CCI-779 therapy, exhibit temporal profiles correlated with the concentration of CCI-779.

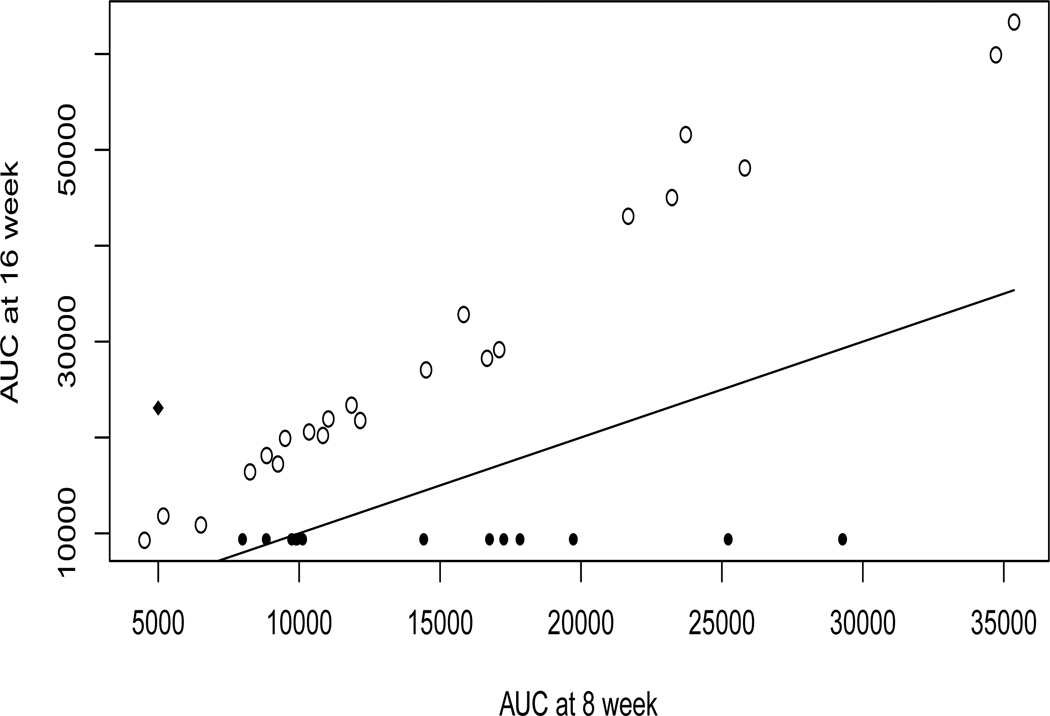

As the log-transformed outcome, CCI-779 cumulative AUC, is roughly normal, we consider the GEE model (2.1) with the identity link. Figure 1 shows that there is an increasing trend for AUC over time of treatments for all patients who were measured at both 8 and 16 weeks. So, we include a binary variable “TIME” - 0 for measurement at 8 week (baseline), 1 for measurement at 16 week - into the GEE model (2.1) to account for the time effect. Further, since the number of genes (p = 12625) greatly outnumbers the number of patients (n = 33) in the study, a covariate screening seems necessary before feeding the data to any sophisticated variable selection methods. Therefore, we first implement the proposed GEES procedure based on different working correlation structures to reduce dimensionality. Then, we combine our procedures with the penalized weighted least-squares (PWLS) method proposed in Xu et al. (2013) to refine the results. To commensurate with the sample size of 33, we first apply the GEES to screen out d = 15 most informative ones from those 12625 genes, while keep the covariate “TIME” in the model. Then, we apply the PWLS to the following GEE model to examine the gene main effects

| (4.1) |

where 𝒜 consists of these 15 selected gene transcripts, GENikj represents the observed gene expression value of the jth selected genes in 𝒜 at the kth time point for the ith subject, and εik is the error term. Without confusion, we still denote the methods as GEES. To compare with the competing methods, we also consider the SIS method proposed in Fan and Lv (2008), in which the SCAD method (Fan and Li, 2001) is used to refine the results. We note that the DC-SIS method proposed by Li et al. (2012) is not applicable to our unbalanced setting.

Figure 1.

A scatter plot of CCI-779 cumulative AUCs against 8 and 16 weeks. The line is the 45 degree line. The solid circles correspond to patients who only had AUC at 8 week, while the solid diamond corresponds to the patient who only had AUC at 16 week

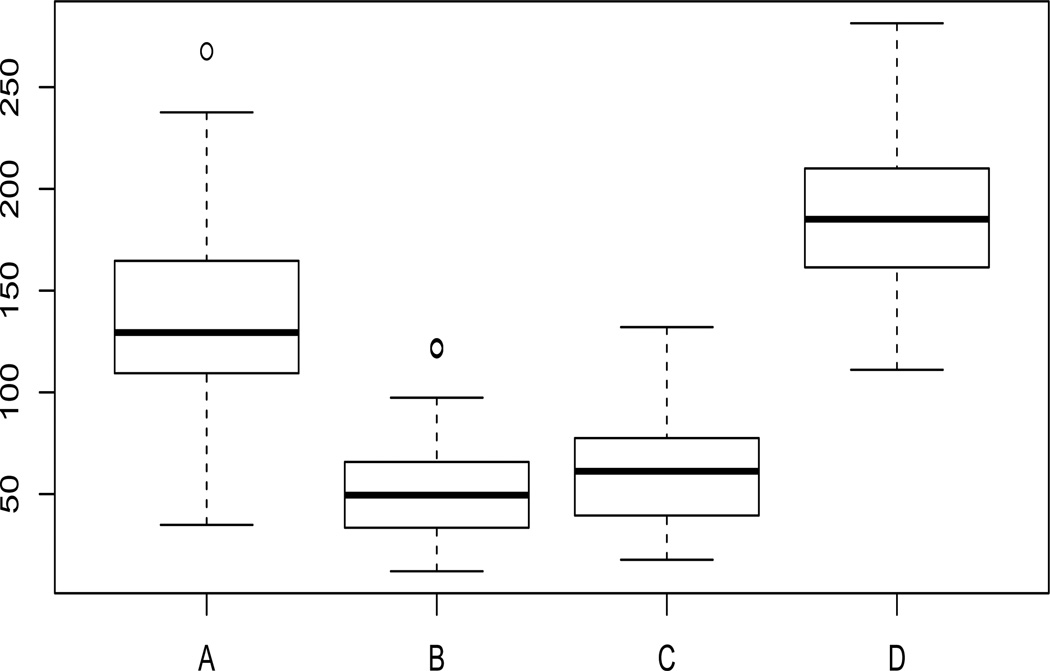

The resulting number of informative genes are summarized in Table 5. We also consider an out-of-sample testing to compare the performance in terms of forecasting. We conduct 100 cross-validation experiments, in each of which we randomly partition the entire data set 𝒟 = {1, …, 33} into a training data set 𝒟1 with 25 subjects and a test data set 𝒟2 with 8 subjects. We fit the GEE model with the identity link respectively for the GEES and the SIS with the training data, then calculate the prediction error in the test data set by using the loss function proposed by Cantoni et al. (2005). Table 5 reports the median of prediction errors from 100 random splits and Figure 2 summarizes the prediction errors using boxplot for procedures GEES_IND, GEES_CS, GEES AR1 and SIS. We can see that, in terms of forecasting, the GEES_CS performs best, which gives the smallest prediction error. Although both the GEES_IND and the SIS assume the independence among the responses, the SIS does not perform as well as the GEES_IND even with more genes selected.

Table 5.

The number of selected informative genes (labeled “Model size”) and the median of prediction errors (“PE”) from 100 random splits for procedures in the advanced renal cancer data set. “GEES” stands for the GEES screening procedure with the PWLS variable selection method. “SIS” stands for the SIS procedure in Fan and Lv (2008), in which the SCAD method is used to refine the results

| Model size | PE | |

|---|---|---|

| GEES_IND | 5 | 129.38 |

| GEES_CS | 5 | 49.48 |

| GEES_AR1 | 5 | 61.21 |

| SIS | 11 | 194.85 |

Figure 2.

Prediction error results by 100 random splits of the advanced renal cancer data set. The procedures from A to D are GEES_IND, GEES_CS, GEES_AR1 and SIS

Our results have strong biological implications. Four overlapping genes have been identified by all the GEES procedures under different working correlation structures: ubiquitin specific peptidase 6 (Tre-2 oncogene) (USP6), α3β1 intergin, beta-actin, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), all of which are relevant to renal functions (Schmid et al., 2003).

5 IGEES: An iterative GEE based sure screening

Like any other univariate screening procedures, the GEES procedure may miss the covariates which are marginally unrelated but jointly related to the responses. In the sprit of the iterative SIS (Fan and Lv, 2008; Fan et al., 2009) and the iterative sure independent ranking and screening (Zhu et al., 2011), we propose an iterative GEE based sure screening (IGEES) procedure to overcome this difficulty.

Step 1. In the initial step, we apply the GEES procedure for samples {(Yi, Xi), i = 1, …, n} to select k1 covariates, where k1 < d and d is the predetermined number of selected covariates. Let 𝒜1 be the set of indices of the selected covariates and Xi𝒜1 be the corresponding m × k1 matrix of selected covariates for the ith subject, i = 1, …, n.

Step 2. Let , and be its complement. Then, we denote the projection of onto the orthogonal complement space of X𝒜1 by , where N = nm. Decompose X̃ into as X𝒜1. Apply the GEES procedure for {(Yi, X̃i), i = 1, …, n} and select k2 covariates. Let 𝒜2 be the corresponding index set.

Step 3. Repeat Step 2 K − 2 times and update the selected covariates with 𝒜1 ∪ … ∪ 𝒜K until k1 + … + kK ≥ d.

In practice, selecting the total number of selected covariates d is challenging, which depends upon the data’s attribute and model complexity. In linear models, Fan and Lv (2008) recommended d = [n/log n] as a sensible choice according to the asymptotic theory, while in models where the response provides less information, Fan et al. (2009) suggested smaller d, such as d = [n/(4 log n)] for logistic regression models, to screen out non-informative variables. In the following simulation, we consider four different values of d: [n/log n], [n/(2 log n)], [n/(3 log n)], and [n/(4 log n)]. The results below show that our method is quite robust to different choices of d, which implies that the model-based choice of d seem to be satisfactory.

Example 3 In this simulation experiment, we consider an unbalanced logistic regression:

where i = 1, …, 400, k = 1, …, mi, with p = 1000, and mis are randomly drawn from a Poisson distribution with mean 5 and increased by 2. We independently generate Xik from a multivariate normal distribution with mean zero and covariance Σ = (σij), where σii = 1 for i = 1, …, p, for all i ≠ 4, and σij = 1/2 for i ≠ j, i ≠ 4 and j ≠ 4. The covariate X4 is marginally independent from, but jointly relevant to, the response variable Y, which typically will not be selected by the GEES. The binary response vector for each cluster has an AR(1) correlation structure with correlation coefficient ρ with two values ρ = 0.5 and 0.8 to represent different within correlation strength. How to decide the sizes kis is also challenging, which is usually depends on model complexity. As suggested by Fan et al. (2009), in this example, we choose k1 = [2d/3] and ki+1 = min(5, d−ki). The following simulation results hint the validity of this strategy.

Table 6 reports the frequency when every single truly informative covariate is selected (𝒫s) as well as when all the truly informative covariates are selected (𝒫a) out of 400 replications based on different predefined thresholding values of d. It reveals clearly that the IGEES can greatly improve the performance of the GEES even in the high within correlation setting. And even with a misspecified working correlation structure, it identifies covariate X4, which is missed by the GEES. Moreover, we observe that both the GEES and the IGEES perform quite robust to different choices of d. In particular, choosing a larger d increases the probability that the IGEES keeps all active variables even when the working correlation structure is misspecified.

Table 6.

The proportion that every single truly active covariate is selected (𝒫s) and the proportion that all truly active covariates are identified (𝒫a) out of 400 replications in Example 3

| 𝒫s | 𝒫a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | ρ | Method | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | ALL | |

| [n/ log n] | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| GEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| GEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| IGEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| GEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| GEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| IGEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| [n/(2 log n)] | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| GEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| GEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| IGEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| GEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| GEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| IGEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| [n/(3 log n)] | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| GEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| GEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| IGEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| GEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| GEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| IGEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |||

| IGEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| IGEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| [n/(4 log n)] | 0.5 | GEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| GEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| GEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| IGEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.98 | |||

| IGEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |||

| IGEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |||

| 0.8 | GEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| GEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| GEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| IGEES_IND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.96 | |||

| IGEES_CS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |||

| IGEES_AR1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

Example 4 (revisit of real data analysis) We further use the advanced renal cancer data set in Section 4.2 to evaluate the performance of the IGEES method. Same as the analysis in Section 4.2, we first apply the proposed IGEES procedure to shrink the dimension to 16 based on different working correlation structures, where the covariate “TIME” is kept in the model. Then, we apply the PWLS to fit (4.1) for refined modeling. Without confusion, call the methods as IGEES. And we compare with the ISIS method proposed in Fan and Lv (2008) with the SCAD method for further refining the results. Table 7 depicts the resulting number of informative gene transcripts and the median of prediction errors from 100 random splits. Together with Table 5, it can be clearly seen that the IGEES_CS has the smallest prediction error. The GEES does not perform as well as the IGEES, partly because the GEES may miss some important features during the screening.

Table 7.

The number of selected informative genes (labeled “Model size”) and the median of prediction errors (“PE”) from 100 random splits for procedures in the advanced renal cancer data set. “IGEES” stands for the IGEES screening procedure with the PWLS variable selection method. “ISIS” stands for the ISIS procedure in Fan and Lv (2008), in which the SCAD method is used to refine the results

| Model size | PE | |

|---|---|---|

| IGEES_IND | 5 | 128.98 |

| IGEES_CS | 5 | 37.94 |

| IGEES_AR1 | 6 | 56.75 |

| ISIS | 10 | 185.07 |

Because the effect of gene expressions on CCI-779 cumulative AUC may be modified by time, we next consider the following GEE model and apply the PWLS to examine the interaction effects of selected genes with time

| (5.1) |

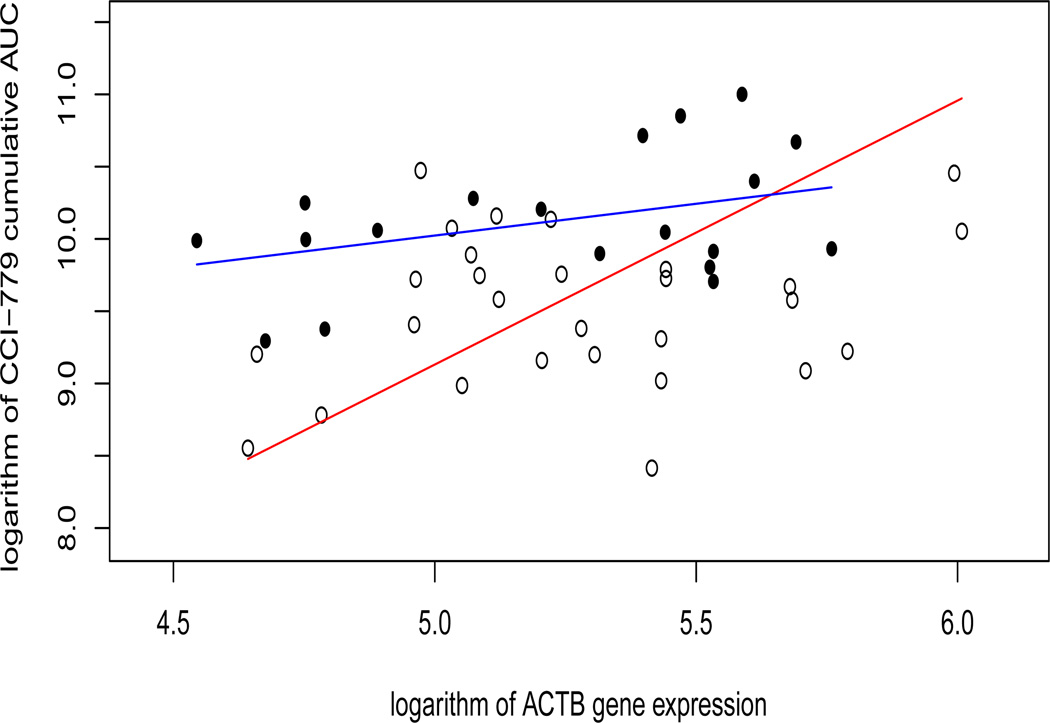

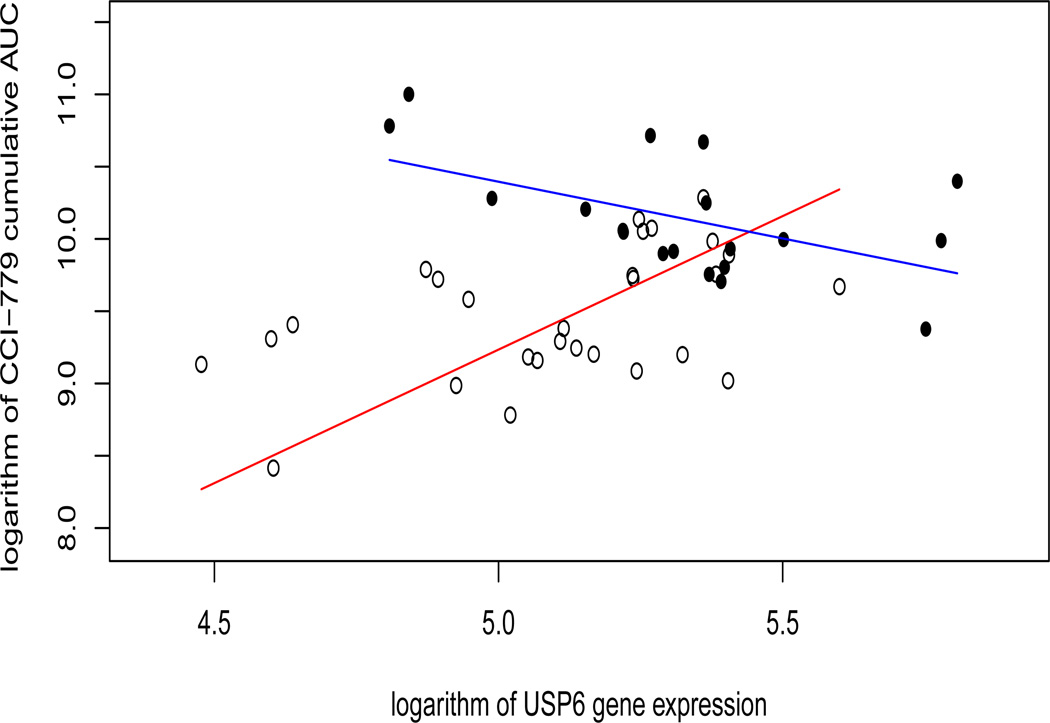

where ℬ consists of final selected gene transcripts based on the GEES and the IGEES procedures. We find that the GEES method couldn’t identify any gene-by-time interactions, but there are two genes with the gene-by-time interaction that have been identified by all the IGEES procedures under different working correlation structures: beta-actin (ACTB), and ubiquitin specific peptidase 6 (Tre-2 oncogene) (USP6). Figures 3 and 4 show the estimated regression lines of the log AUC on these two genes at 8 and 16 weeks, respectively. The time-interaction effects are obvious - both genes seem to regularize the CCI-779 metabolism at week 8, but not at week 16. These two genes may be related to renal functions at early stage of treatment; see Boni et al. (2005) for more detail.

Figure 3.

CCI-779 cumulative AUC versus ACTB gene expression level. The unfilled circles correspond to data at week 8, while the filled circles correspond to data at week 16. The red and blue lines denote the estimated regression lines for data points at 8 and 16 weeks, respectively

Figure 4.

CCI-779 cumulative AUC versus USP6 gene expression level. The unfilled circles correspond to data at week 8, while the filled circles correspond to data at week 16. The red and blue lines denote the estimated regression lines for data points at 8 and 16 weeks, respectively

6 Discussion

The original idea of sure independence screening stems from studying the marginal effect of each covariate, which presents a powerful method for dimension reduction and has been widely applied for independent data. But these applications may not be effective for time course data as they would ignore within-subject correlations. To fill this gap, we propose the GEES, a new computationally efficient screening procedure based only on a single evaluation of the generalized estimating equations in ultrahigh dimensional time course data analysis. We show that, with p increasing at the exponential rate of n, it enjoys the sure screening property with vanishing false selection rate even when the working correlation structure is misspecified. An iterative GEES (IGEES) is also proposed to enhance the performance of the GEES for more complicated ultrahigh dimensional time course. The numerical studies demonstrate its improved performance compared with existing screening procedures.

Once dimension reduction is achieved, we can use some regularized regression techniques, such as the penalized GEE method (Wang et al. 2012) and the PWLS method (Xu et al. 2013), to reach the final model.

Several open problems, though, still exist. Even if the proposed procedure is capable of retaining important covariates without including too many false positives no matter what working correlation matrix is used, the mis-specification of the working correlation will indeed affect the efficiency of parameter estimation in the regularization step. It is therefore important for us to discuss the impact of mis-specification in a more systematic fashion. Moreover, to retain the covariates which are marginally unrelated but jointly related with the responses, we propose an iterative GEES procedure, along the line of Fan and Lv (2008) and Fan et al. (2009). The validity of such a strategy is implied by our numerical studies. But future work is warranted to study the relevant theoretical properties, although the theory is elusive even for independent cases.

Finally, in the presence of missing responses at some time points, our implicit assumption is missing completely at random (MCAR), under which generalized estimating equations (GEE) yield consistent estimates (Liang and Zeger, 1986). Such an assumption is applicable to our motivating example, as patients missed their measurements due to administrative reasons. However, when the missing data mechanism is missing at random (MAR), that is the probability of missing a particular outcome at a time-point depends on observed values of that outcome and the remaining outcomes at other time points, GEE has to be modified so as to incorporate missing mechanisms. This is beyond the current scope of the work and would warrant further investigations.

Acknowledgments

The research described here was supported by Scientific Research Foundation of Southeast University, a grant from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong and a grant from the NIH.

Appendix

To prove Theorems 1 and 2, we will need the Bernstein’s inequality (see, e.g. van der Vaart and Wellner, 1996) and a lemma of Wang (2011) (Lemma C.1). We re-state the results.

Lemma 7.1. (Bernstein's inequality) Let Z1, …, Zn be independent random variables with mean zero and satisfy

for every l ≥ 2 and all i and some positive constants M and Vi. Then

for V > V1 + … + Vn.

Lemma 7.2. (Wang, 2011) Let and ∇(β) = −∂ Ḡ(β)/∂β. Then, we have

where

with

Proof of Theorem 1. According to the definition of ℳ̂γn, we know that {ℳ0 ⊂ ℳ̂γn} is equivalent to {minj∈ℳ0|Ĝj(0)| ≥ γn}. Then, it is easy to see that

Let and Ḡj(0) be the jth element of Ḡ(0). Then for each j ∈ ℳ0, we have

We first consider the term P(|Ḡj(0)| < 2γn), j ∈ ℳ0. Under conditions (C2), (C4) and (C5), we have that

for every j ∈ ℳ0, where the second inequality is due to the bound minj∈ℳ0 |ḡj(0)| ≥ c3n−κ in condition (C5), the last inequality follows from Lemma 7.1, and c is a positive constant depending on c2. Hereafter, we use c to denote a generic positive constant which may vary for every appearance.

Next, let ej be a p-dimensional basis vector with the jth element being one and all the other elements being zero, 1 ≤ j ≤ p. Then,

| (7.1) |

where the third inequality follows from condition (C3), and the last inequality follows from conditions (C2), (C4) and the Markov’s inequality.

Therefore, under condition (C6), we have

Proof of Theorem 2. Note that γn ≤ |Ĝj(0)| ≤ |Ḡj(0)| + |Ḡj(0) − Ĝj(0)| for every j ∈ ℳ̂γn. Thus, we have

Consequently, it is sufficient to provide upper bounds on I1 and I2 that hold with a high probability, respectively. Now suppose that ‖Ḡ(0) − ḡ(0)‖∞ ≤ γn/4. Then |Ḡj(0)| ≥ γn/2 implies that |ḡj(0)| ≥ γn/4. Hence, under ‖Ḡ(0) − ḡ(0)‖∞ ≤ γn/4, we have

Consequently, it follows that

under ‖Ḡ(0) − ḡ(0)‖∞ ≤ γn/4 and ‖Ĝ(0) − Ḡ(0)‖∞ ≤ γn/2, which implies that we only need to provide an upper bound on when ‖Ḡ(0) − ḡ(0)‖∞ ≤ γn/4 and ‖Ĝ(0) − Ḡ(0)‖∞ ≤ γn/2 hold with a high probability.

Let . Note that ḡ(β0) = EXτA1/2(β0)R̄−1A−1/2(β0)(Y − μ(β0)) = 0. Thus, we have

where β̃ lies on the line segment between β0 and 0 so that β̃ ∈ ℬ and M = E{∇(β̃)}Σ−1/2. Since

we have . Now, we only need to provide an upper bound on λmax(E{∇(β̃)}). Lemma 7.2 implies that

We first consider term λmax(E{H̄ (β)}), β ∈ ℬ. Under conditions (C2) and (C7), for any unit length pn-dimensional vector r, we have

Therefore,

for any β ∈ ℬ. Next, we consider term E{Ē (β)}. Let D̄i(β) = diag(μi1(β0)− μi1(β), …, μim(β0) − μim(β)). Then, we have

which can be decomposed as

where

For any r ∈ Rpn with ‖r‖2 = 1,

The application of Taylor expansion yields that

where β* lies on the line segment between β0 and β. Under conditions (C2), (C3), and (C7), we have

Hence, for any β satisfying ‖β‖2 ≤ cβ,

which implies that

Similarly, we can show that for s = 2, 3, 4. Thus

We can also have , and then for β ∈ ℬ. Consequently, under condition (C7), we have

Further, note that . Thus, we have

which results in, combining ‖Ḡ(0) − ḡ(0)‖∞ ≤ γn/4 and ‖Ĝ(0) − Ḡ(0)‖∞ < γn/2,

On the other hand, invoking Lemma 7.1, we have

s when log pn = o(n1−2κ). Similar to the inequality (7.1) in the proof of Theorem 1, we have

Therefore,

which concludes the proof.

References

- 1.Balan RM, Schiopu-Kratina I. Asymptotic results with generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data. Annals of Statistics. 2005;32:522–541. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bondell HD, Krishna A, Ghosh SK. Joint variable selection for fixed and random effects in linear mixed-effects models. Biometrics. 2010;66:1069–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2010.01391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boni JP, Leister C, Bender G, Fitzpatrick PV, Twine N, Stover J, Dorner A, Immermann F, Burczynski M. Population pharmacokinetics of CCI-779: Correlations to safety and pharmacogenomic responses in patients with advanced renal cancer. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2005;77:76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantoni E, Filed C, Flemming JM, Ronchetti E. Longitudinal variable selection by cross-validation in the case of many covariates. Statistics in Medicine. 2005;26:919–930. doi: 10.1002/sim.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan J, Feng Y, Song R. Nonparametric independence screening in sparse ultra-high dimensional additive models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2011;116:544–557. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2011.tm09779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan J, Li R. Variable selection via nonconcave penalized likelihood and its oracle properties. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:1348–1360. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan J, Lv J. Sure independence screening for ultrahigh dimensional feature space (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2008;70:849–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2008.00674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan J, Samworth R, Wu Y. Ultrahigh dimension variable selection: beyond the linear model. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2009;10:1829–1853. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan J, Song R. Sure Independence Screening in Generalized Linear Models with NP-dimensionality. Annals of Statistics. 2010;38:3567–3604. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu WJ. Penalized Estimating Equations. Biometrics. 2003;59:126–132. doi: 10.1111/1541-0420.00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li R, Zhong W, Zhu L. Feature screening via distance correlation learning. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2012;107:1129–1139. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2012.695654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal Data Analysis Using Generalised Linear Models. Biometrika. 1986;73:12–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin L, Sun J, Zhu L. Nonparametric feature screening. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 2013;67:162–174. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmid H, Cohen CD, Henger A, Irrgang S, Schlöndorff D, Kretzler M. Validation of endogenous controls for gene expression analysis in microdissected human renal biopsies. Kidney International. 2003;64:356–360. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L. GEE analysis of clustered binary data with diverging number of covariates. Annals of Statistics. 2011;39:389–417. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Zhou J, Qu A. High-dimensional penalized generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Biometrics. 2012;68:353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Vaart AW, Wellner JA. Weak Convergence and Empirical Processes. New York: Sprigner-Verlag; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie M, Yang Y. Asymptotics for generalized estimating equations with large cluster sizes. Annals of Statistics. 2003;31:310–347. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu P, Fu W, Zhu L. Shrinkage estimation analysis of correlated binary data with a diverging number of parameters. Science China Mathematic. 2013;56:359–377. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao SD, Li Y. Principled sure independence screening for Cox models with ultra-high-dimensional covariates. Journal of Multivariate Analysis. 2012a;105:397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jmva.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao SD, Li Y. Sure screening for estimating equations in ultra-high dimensions. 2012b http://arxiv.org/pdf/1110.6817.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu L, Li L, Li R, Zhu L. Model-free feature screening for ultrahigh-dimensional data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2011;106:1464–1475. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2011.tm10563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]