Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a metabolic disorder commonly associated with obesity. A subset of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients further develops nonalcoholic steatohepatitis that is characterized by chronic liver injury, inflammation, and fibrosis. Recent work has implicated the autophagy pathway in the mobilization and oxidation of triglycerides from lipid droplets. However, whether impaired autophagy in hepatocytes drives excess fat accumulation in the liver remains controversial. In addition, the role of autophagy in protecting the liver from gut endotoxin-induced injury has not been elucidated. Here we generated mice with liver-specific autophagy deficiency by the conditional deletion of focal adhesion kinase family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa (also called Rb1cc1), a core subunit of the mammalian autophagy related 1 complex. To our surprise, mice lacking FIP200 in hepatocytes were protected from starvation- and high-fat diet-induced fat accumulation in the liver and had decreased expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism. Activation of the de novo lipogenic program by liver X receptor was impaired in FIP200-deficient livers. Furthermore, liver autophagy was stimulated by exposure to low doses of lipopolysaccharides and its deficiency-sensitized mice to endotoxin-induced liver injury. Together these studies demonstrate that hepatocyte-specific autophagy deficiency per se does not exacerbate hepatic steatosis. Instead, autophagy may play a protective role in the liver after exposure to gut-derived endotoxins and its blockade may accelerate nonalcoholic steatohepatitis progression.

Metabolic syndrome has become a global epidemic that markedly increases the risk for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (1–3). Excess accumulation of triglycerides in the liver is a defining feature of NAFLD that affects nearly one third of adults in the United States and is frequently observed in obese children (4–7). Although patients with hepatic steatosis often have normal liver function, a subset of affected individuals develops nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is characterized by chronic liver injury, inflammation, and fibrosis (8). Whether NASH represents a clinical sequela of fatty liver in the natural history of NAFLD remains currently unknown. However, it has been generally agreed that obesity increases the risk for fatty liver disease and NASH, and as such, NASH pathogenesis is tightly linked to chronic fat accumulation in the liver. The regulatory networks that control hepatic lipid metabolism have been a focus of research in the past 2 decades (9–11). Several recent genome-wide association studies have identified candidate loci that contribute to the risk for hepatic steatosis (12–14). The pathogenic mechanisms underlying NASH progression in a subset of patients remain elusive; several factors have been implicated, including gut-derived bacterial toxins, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative/endoplasmic reticulum stress (15–17).

Autophagy is a conserved cellular process that contributes to nutrient and organelle homeostasis (18, 19). Recent studies have demonstrated that autophagy is impaired in the liver in insulin resistant state (20, 21). Furthermore, autophagy machinery has been found to associate with lipid droplets and participate in the hydrolysis and oxidation of lipids (22). However, conflicting results have been reported regarding the role of authophagy in the development of hepatic steatosis (22–24). A notable histological observation in NASH livers is the presence of ballooning hepatocytes containing Mallory-Denk bodies, intracellular protein aggregates containing ubiquitinated proteins and p62, a protein selectively degraded through autophagy (25–29). As such, autophagy impairments potentially provide a link between hepatic steatosis and liver injury in NASH.

Autophagic degradation of cellular components is a highly regulated process that is responsive to nutritional cues and stress signals. In mammals, the autophagy-related protein (ATG)-1 complex consists of several subunits, including adaptor protein focal adhesion kinase family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa (FIP200), unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1), ATG101, and ATG13, and integrates diverse signaling pathways to control the initiation of autophagosome formation (30). Previous studies have demonstrated that FIP200 is required for autophagy induction in several cell types, including fibroblasts, neurons, and neural stem cells (31–33). However, the role of FIP200 in the regulation of liver autophagy and key aspects of NAFLD pathogenesis has not been explored. Using mice with liver-specific FIP200 deficiency, we demonstrated that autophagy inhibition in hepatocytes attenuates the program of de novo lipogenesis and reduces hepatic steatosis. Interestingly, liver autophagy is induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and protects the mice against endotoxin-induced liver injury. These observations uncouple hepatic steatosis from liver injury and raise the possibility that autophagy impairment may serve as a unique pathogenic hit that accelerates NASH progression.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were performed according to procedures approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals. FIP200 flox/flox mice were crossed with Albumin-Cre transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratory) to generate liver-specific FIP200 knockout mice (FILKO) (34). The high-fat diet (HFD) used for experiment was purchased from Research Diets (D12492). Genotyping of FILKO mice were performed using primer P1, P2, and P3 as previously described (34). For treatments with LPS and leupeptin (Fisher Scientific), wild-type C57BL/6 male mice were fed a HFD for 1 month and treated with a single ip injection of LPS or saline (0.8 mg/kg) at 11:00 am and a single dose of leupeptin (40 mg/kg) or PBS at 2:00 pm. Food was removed from 2:00 pm to 5:00 pm before the tissue harvest. For LPS treatments, control and FILKO mice received a single ip injection of 0.3 mg/kg LPS or saline. The tissues from treated mice were harvested 24 hours after the injection. For the TO-901317 gavage experiment, the animals were gavaged daily with TO-901317 (25 mg/kg) dissolved in sunflower oil for 2 consecutive days. The tissues were harvested 7 hours after the second gavage.

In vivo adenoviral transduction and metabolic analyses

Three-month-old FIP200 flox/flox male mice (three to five per group) fed a HFD for 1 month were transduced with purified green fluorescent protein (GFP) or Cre adenoviruses through tail vein injection (0.2 OD per mouse), as previously described (35). The mice were killed 7 days after transduction under a 16-hour-fasted condition. The titers of all adenoviruses were determined based on the expression of GFP and adenoviral gene AdE4 before use to ensure similar doses were administered in the studies. Triglycerides, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations were measured using commercial assay kits (Sigma and Stanbio Laboratory).

Protein and RNA analysis

Immunoblotting studies were performed using specific antibodies for FIP200 (10043–2-AP; Proteintech Group), LC3 (LC3–5F10; Nanotools), p62 (PW9860; Enzo Life Sciences), Ulk1 (A7481; Sigma), and Atg7 (AP1813b; Abgent). The fractionation of liver lysates to separate soluble and insoluble proteins was performed following a published protocol (36). Hepatic gene expression was analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using specific primers listed in Supplemental Table 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org. Data represent mean ± SEM.

Transmission electron microscopy (EM)

Two-month-old control and FILKO male mice were first perfused with Sorensen's buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and then Karnovsky's fixative buffer. The liver is postfixed in Karnovsky's fixative buffer for 24–48 hours before embedding. EM was performed by the Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory at the University of Michigan. The images were acquired using a Philips CM-100 transmission electron microscope.

Immunohistochemistry, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Oil Red O staining, and Sirius Red staining

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and then rehydrated through a graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 80%, and 70%). Immunohistochemistry using antibodies against p62 (PW9860; Enzo Life Sciences) or ubiquitin (P4D1, sc-8017; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was performed after microwave antigen retrieval (20 min) in 10 mM sodium citrate. A 5% solution of bovine serum albumin in PBS with 0.5% Tween 20 was used as blocking buffer. Sections were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Immunoperoxidase staining was detected using the Vectastain Elite ABC and the diaminobenzidine substrate kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories). Nuclei were counterstained with Gill's hematoxylin. For Sirius Red staining, paraffin sections were dewaxed and hydrated followed by nuclear counterstain using hematoxylin and washing under running tap water. The sections were then stained in picro-sirius red for 1 hour, washed with two changes of acidified water, dehydrated, and cleared in xylene before mounting using a resinous medium. H&E staining and Oil Red O staining were performed as previously described (37).

Stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy

SRS microscopy was used to evaluate the mount of lipid droplets in hepatic cells. Briefly, a Ti-sapphire laser of 80 MHz repetition rate and 140 fs pulse duration (Chameleon Vision; Coherent) pumped an optical parametric oscillator (Chameleon Compact; Angewandte Physik & Elektronik), providing the pump beam at frequency ωp and the Stokes beam at frequency ωS. The two beams were collinearly combined and directed into a laser-scanning microscope (FV300; Olympus). A water immersion objective (NA = 1.2; Olympus) was used for laser focusing. An acoustooptic modulator (15180–1.06-LTDGAP; Gooch & Housego) was used to modulate the intensity of the Stokes beam at 2.6 MHz. The pump beam was detected in the forward by a photodiode (S3071; Hamamatsu Photonics) and the stimulated Raman loss signal was extracted by a lock-in amplifier (HF2LI; Zurich Instruments). The liver specimens were sectioned into a series of 50-μm-thickness tissue slices by a vibratome (OTS-4500; EMS). A single slice was sandwiched between two coverslips for SRS imaging of lipids with the beating frequency (ωp-ωS) tuned to 2850 cm−1.

Results

Hepatocyte-specific FIP200 deficiency impaired autophagy in the liver

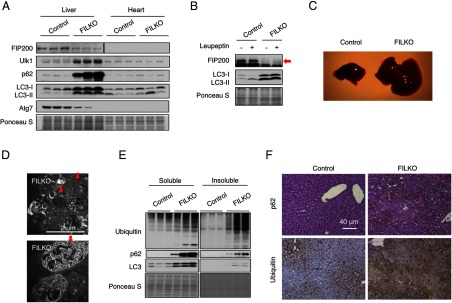

To examine the role of autophagy in the pathogenesis of NAFLD, we conditionally deleted FIP200 in hepatocytes by breeding FIP200 flox/flox mice with albumin-Cre transgenic mice (34). FIP200 protein expression was significantly reduced in the liver, but not in other tissues, in FILKO mice (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1). Interestingly, ULK1 protein levels were increased, perhaps a compensatory response to the absence of FIP200, whereas ATG7 was reduced in FIP200-deficient livers. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of FIP200 resulted in a marked accumulation of p62, an autophagosome-associated protein that is degraded via autophagy (Figure 1A). Interestingly, both LC3-I and LC3-II levels were elevated in the FILKO mouse livers, suggesting that, in addition to its role in the regulation of autophagy initiation, FIP200 may also play a role in other steps of autophagy, including lysosomal degradation of autophagy cargoes. No differences in LC3 and p62 protein levels were observed in the heart and epidermal white fat (eWAT) between control and FILKO mice (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1). Autophagy flux analysis indicated that the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II was impaired in the absence of FIP200 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

FILKO mice have defective autophagy in the liver. A, Immunoblots of autophagy-related proteins in the liver and heart from control and FILKO mice. Ponceau S stain serves as a loading control. B, Liver autophagy flux assay. Red arrow indicates endogenous FIP200. C, Image of livers from 1.5-month-old chow-fed control and FILKO mice. D, EM images showing abnormal intracellular structures in FILKO mouse livers. Red arrows point to abnormal vacuoles containing a large number of small vesicles and structures similar to multilamellar bodies. E, Immunoblots of ubiquitin, p62, and LC3 in soluble and insoluble fractions of liver lysates from control and FILKO mice. F, Immunohistochemical staining of p62 and ubiquitin on liver sections. The slides were counterstained with H&E (for p62) or hematoxylin (for ubiquitin). The presence of p62 and ubiquitin was indicated by brown reaction products.

FILKO mice exhibit hepatomegaly associated with swollen hepatocytes as early as 1 month of age, similar to other autophagy-deficient mouse models (Figure 1C). Using transmission EM, we observed clusters of abnormal vacuoles containing smaller vesicles and numerous multilamellar bodies in FIP200-deficient hepatocytes, likely as a consequence of autophagy defects (Figure 1D). Accordingly, the accumulation of insoluble protein aggregates containing ubiquitinated proteins and p62 was increased in FILKO mouse livers, as shown by immunoblotting analyses and immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1, E and F). The formation of ubiquitin-positive aggregates has been reported to result from reduced turnover of p62 when autophagy is impaired (38, 39). These ubiquitin- and p62-positive aggregates are strikingly reminiscent of the Mallory-Denk body, a prominent feature of hepatocytes from NASH patients (25), suggesting that a functional deficit of autophagy activity may play a role in NASH pathogenesis.

Chronic autophagy inhibition in hepatocytes prevents starvation-induced triglyceride accumulation in the liver

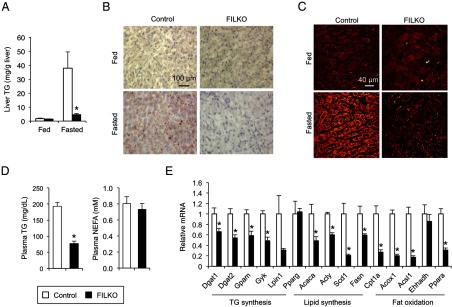

Recent studies demonstrated that autophagy contributes to triglyceride hydrolysis and fat oxidation and may play a role in the development of hepatic steatosis (22). To assess the effects of autophagy deficiency on hepatic lipid metabolism, we measured liver triglyceride content in control and FILKO mice fed normal chow under fed and fasted conditions. Liver triglyceride content is relatively low under fed condition and markedly increases upon starvation due to increased adipose tissue lipolysis. As expected, lipid deposition in the liver was modest under fed condition in both groups (Figure 2A). In contrast, hepatic triglyceride content was markedly lower in FILKO mice after overnight starvation. This result was further confirmed using Oil Red O staining (Figure 2B) and SRS microscopy, a label-free method to visualize intracellular lipid droplets (Figure 2C). Although plasma triglyceride levels were lower in FILKO mice, the concentrations of nonesterified fatty acids (NEFAs) were similar between the two groups (Figure 2D). Plasma insulin and glucagon levels were also similar (Supplemental Figure 2A). The decrease in hepatic triglyceride content in FILKO mice was strikingly similar to two previous studies in which autophagy was disrupted by hepatocyte-specific deletion of Atg7 (23, 24). However, opposite effects on liver lipids were observed in a separate study using liver-specific Atg7 knockout mice (22). The causes of this discrepancy remain currently unknown.

Figure 2.

Effects of liver-specific FIP200 deficiency on hepatic triglycerides. A, Liver triglyceride content of chow-fed control (white columns) and FILKO (black columns) mice under fed or fasted conditions. B, Oil Red O staining of liver sections. C, SRS microscopy imaging of livers from control and FILKO mice. Lipid droplets were shown as yellow dots in hepatocytes. D, Plasma triglyceride and NEFA levels in fasted mice. E, qPCR analysis of mRNA expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism in control and FILKO livers under fasted condition. Data in A, D, and E represent mean ± SE. *, P < .05.

We next performed qPCR analysis to assess mRNA expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism (Figure 2E). We found that many genes involved in de novo lipogenesis, including ATP-citrate lyase (Acly), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Acaca), fatty acid synthase (Fasn), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (Scd1), and triglyceride synthesis, including diacyl-glycerol acyltransferase 1 (Dgat1), Dgat2, mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (Gpam), and glycerol kinase (Gyk), were down-regulated in FILKO mouse livers. Interestingly, mRNA expression of PPARα and genes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation, such as carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (Cpt1a), peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidase (Acox1), and acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 1 (Acsl1), was also reduced in FIP200 deficiency livers, suggesting that autophagy exerts effects on the expression of both lipogenic and fat oxidation genes.

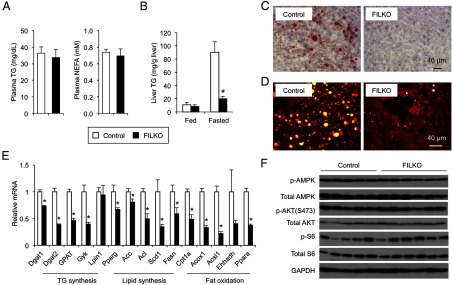

Chronic and acute FIP200 deficiency reduces HFD-induced hepatic steatosis and attenuates lipogenic gene expression

Chronic high-fat feeding results in obesity, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in rodents. To determine whether autophagy deficiency exacerbates diet-induced fatty liver, we subjected control and FILKO mice to high-fat feeding for 5 weeks and measured hepatic fat content. Plasma triglyceride and NEFA levels were similar between these two groups (Figure 3A). Although liver triglyceride content was similar between the two groups in the fed state, it was significantly reduced in FILKO mouse livers after starvation (Figure 3, B–D). As such, hepatic autophagy deficiency reduced fat accumulation in the liver in fasted mice. Interestingly, although fasting plasma glucagon levels were similar, plasma insulin concentrations were lower in HFD-fed FILKO mice under fed and fasted conditions (Supplemental Figure 2B). Similar to mice fed standard chow, the expression of many genes involved in hepatic lipid metabolism was lower in FIP200-deficient livers (Figure 3E). The decrease in hepatic lipid content and gene expression may be due to changes in nutrient signaling in the liver. We next examined the status of several major metabolic signaling pathways, including the AMP-activated protein kinase, AKT, and mammalian target of rapamycin pathways. We did not observe significant differences in phosphorylated and total AMP-activated protein kinase, AKT, and S6 protein levels (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Liver-specific FIP200 deficiency does not exacerbate diet-induced hepatic steatosis. A, Plasma triglyceride and NEFA concentrations under fasted condition. B, Liver triglyceride content of HFD-fed control (white columns) and FILKO (black columns) mice under fed and fasted conditions. C, Oil Red O staining of liver sections from control and FILKO mice under fasted condition. D, SRS microscopy imaging of liver from control and FILKO mice under fasted condition. Lipid droplets were shown as yellow dots in hepatocytes. E, qPCR analysis of mRNA expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism in control and FILKO liver under fasted condition. Data in A, B, and E represent mean ± SE. *, P < .05. F, Immunoblots of total lysates from control and FILKO mouse livers under fed condition. TG, triglyceride.

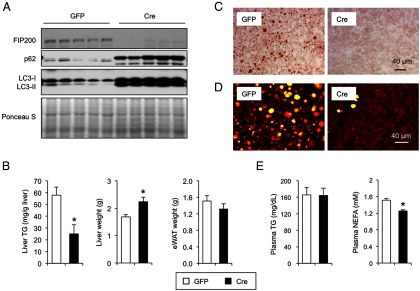

To rule out the possibility that chronic deficiency of FIP200 in hepatocytes may have unforeseen effects on liver development and function, we next performed studies in mice following acute deletion of FIP200 in the liver. We transduced HFD-fed FIP200 flox/flox mice with recombinant adenoviruses expressing GFP or Cre recombinase via tail vein injection. Recombinant adenoviruses efficiently transduce hepatocytes and have been widely used to study liver gene expression and physiology (40). Compared with GFP, adenoviral-mediated Cre expression nearly abolished FIP200 expression in the liver. Similar to FILKO livers, acute FIP200 deletion in adult mice resulted in marked accumulation of p62 and LC3 proteins, indicative of defective autophagy (Figure 4A). Although epididymal white fat (eWAT) mass remained similar, the liver was significantly enlarged after acute FIP200 deletion (Figure 4B). Measurements of liver triglyceride content revealed that adenoviral Cre-mediated ablation of FIP200 significantly lowered liver triglyceride content (Figure 4, B–D). Plasma triglycerides remained largely unchanged, whereas NEFA levels were slightly lower in mice transduced with Cre adenovirus (Figure 4E). Together these studies demonstrate that although autophagy plays an important role in hepatic lipid metabolism, its deficiency does not result in an excess lipid accumulation in the liver under physiological and pathological conditions.

Figure 4.

Acute deletion of FIP200 in the HFD-fed mouse liver lowers liver triglyceride content. A, Immunoblots of autophagy proteins in the livers of FIP200 flox/flox mice transduced with GFP (white columns) or Cre (black columns) adenoviruses. B, Liver and eWAT weight and liver triglyceride content in fasted FIP200 flox/flox mouse transduced with GFP or Cre adenovirus. C and D, Oil Red O staining (C) and SRS microscopy imaging (D) of transduced mouse livers under fasted condition. E, Plasma triglyceride and NEFA concentrations under fasted condition. Data in B and E represent mean ± SE. *, P < .05.

FIP200 deficiency impairs the induction of lipogenic genes by liver X receptor (LXR)

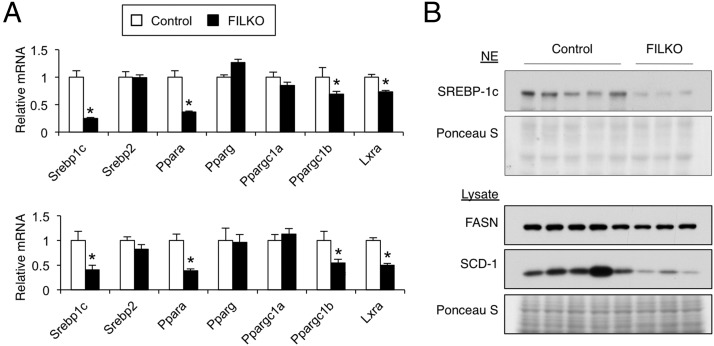

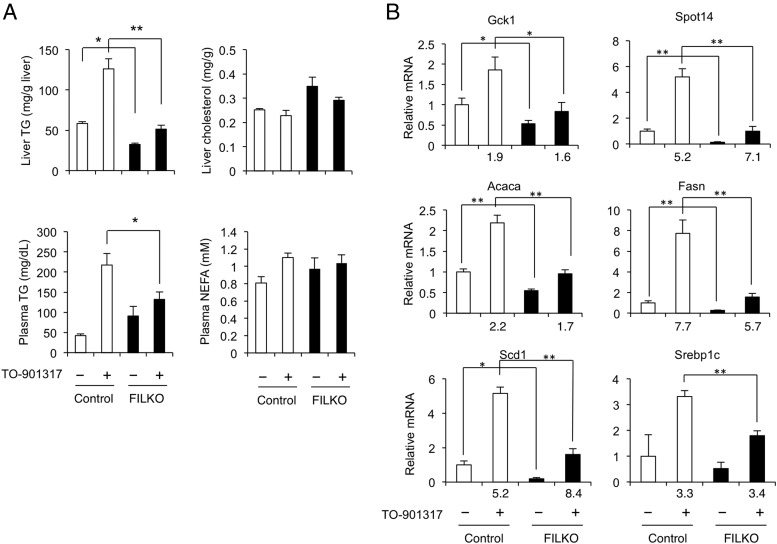

The LXR/sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) pathway is a major regulator of the program of de novo lipogenesis and triglyceride synthesis in the liver (9, 41). To determine whether the reduction in lipogenic gene expression in FIP200-deficient livers is due to the attenuation of LXR/SREBP1c signaling, we examined mRNA and protein expression of SREBP1c. SREBP1c mRNA expression was markedly lower in FILKO mouse livers under both chow- and HFD-fed conditions (Figure 5A). Consistently, the cleaved nuclear isoform of SREBP1c protein, which is transcriptionally active, and fatty acid synthase and stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 protein levels in the liver were also reduced when FIP200 was absent (Figure 5B). SREBP1c is a direct target gene of LXR. To determine whether FIP200 deficiency in hepatocytes impairs the induction of hepatic lipogenesis in response to LXR activation, we gavaged control and FILKO mice with vehicle or TO-901317 and analyzed hepatic and plasma lipids. As expected, hepatic and plasma triglyceride levels were markedly elevated in response to TO-901317 in control mice (Figure 6A). In contrast, the accumulation of triglycerides in the hepatic and plasma compartments was significantly diminished in FILKO mice. No differences were observed for liver cholesterol and plasma NEFA levels. Although hepatic mRNA expression of Srebp1c, Fasn, Scd1, Acaca, Gck1, and Spot14 was robustly induced by TO-901317 in control mice, their mRNA levels were significantly lower in the livers from FILKO mice (Figure 6B). Reduced lipogenic gene expression was observed under basal condition and after TO-901317 treatments. These results suggest that FIP200 deletion-mediated autophagy deficiency significantly diminishes the induction of lipogenic gene program in response to LXR activation, which could contribute to decreased triglyceride content in FILKO.

Figure 5.

The LXR/SREBP1c pathway is impaired in FILKO livers. A, qPCR analysis of hepatic gene expression in control (white columns) and FILKO (black columns) mice in chow fed (top panel) and HFD-fed (bottom panel) conditions. Data represent mean ± SE. *, P < .05. B, Immunoblots using liver nuclear extracts (NE; top two panels) and total liver lysates (lower three panels).

Figure 6.

Metabolic parameters and hepatic gene expression in mice treated with an LXR agonist. A, Liver and plasma lipid levels in control (white columns) and FILKO (black columns) mice treated with vehicle (−) or TO-901317 (+) under fed condition. B, qPCR analysis of hepatic gene expression in treated mice. Fold induction by TO-901317 is indicated. Data represent mean ± SE. *, P < .05; **, P < .01.

Liver autophagy protects mice from endotoxin-induced liver injury

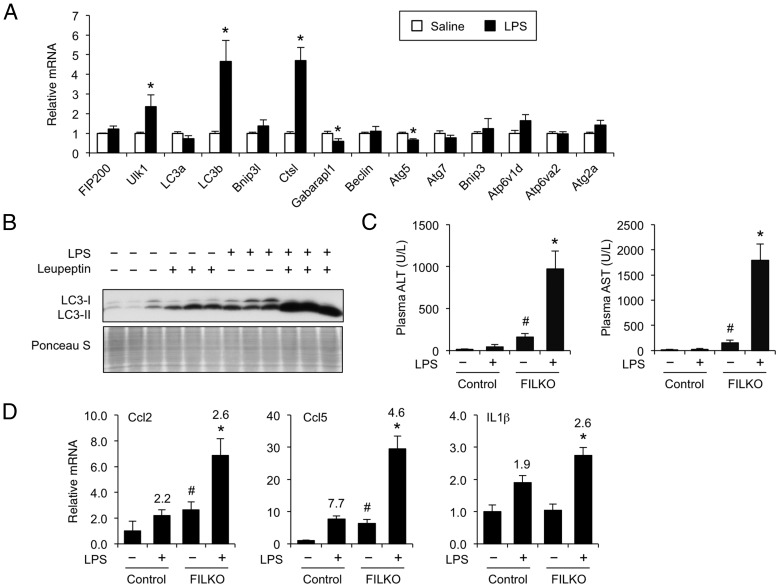

Chronic exposure to gut-derived endotoxins has been proposed to promote NASH progression in humans (15, 17). Previous studies demonstrated that low-dose LPS treatments recapitulate this pathogenic event in diet-induced obese mice (15, 42). Bacterial endotoxins augment the production of proinflammatory cytokines that impair hepatic metabolism and exacerbate liver injury. Because autophagy plays a central role in the clearance of bacterial pathogens, we postulated that this pathway might be engaged in response to endotoxin exposure. To determine the effects of bacterial endotoxins on autophagy, we treated HFD-fed obese mice with a single ip injection of saline or LPS (0.8 mg/kg) and analyzed hepatic gene expression. As expected, LPS treatment induced the expression of proinflammatory genes, including Ccl2, Nos2, and Stat1 (data not shown). Analysis of autophagy gene expression indicated that the mRNA level of Ulk1, a core component of the mammalian ATG1 complex that regulates the initiation of autophagy, was significantly induced in response to LPS (Figure 7A). Several other genes in the autophagy pathway, including LC3b and Ctsl, were also stimulated by endotoxin treatments. To assess the effects of LPS on autophagy activity, we performed an in vivo autophagy flux assay using leupeptin, a lysosomal protease inhibitor. The rate of LC3-II accumulation after leupeptin treatments is indicative of the flux through the autophagy pathway (43, 44). As shown in Figure 7B, autophagy flux was markedly increased in LPS-treated mouse livers.

Figure 7.

Autophagy is induced in the liver in response to LPS. A, qPCR analysis of autophagy gene expression in the livers from mice treated with saline (white columns) or LPS (black columns). The mice were retreated with a single ip injection at 4:00 pm and harvested at 11:00 pm. Data represent mean ± SE. *, P < .05. B, Autophagy flux assay in treated mice. The increase of LC3-II after leupeptin injection is indicative of the rate of autophagy flux. Ponceau S-stained blot serves as a loading control. C, Plasma ALT and AST of HFD-fed control and FILKO mice injected with saline or LPS. D, qPCR analysis of hepatic gene expression. Fold induction by LPS is indicated above the columns. Data in C and D represent mean ± SE. *, P < .05, FILKO/LPS vs FILKO or LPS alone; #, P < .05, FILKO vs control.

We next examined the role of autophagy in potentially protecting the liver from endotoxin-induced liver injury. We treated HFD-fed control and FILKO mice with saline or a single dose of LPS (0.3 mg/kg). This low dose of LPS alone had modest effects on plasma AST and ALT levels (Figure 7C), markers of liver injury. In addition, AST and ALT levels were moderately elevated in mice with liver-specific deficiency of FIP200. In contrast, LPS treatment of FILKO mice resulted in a marked increase in plasma AST and ALT levels, indicating that FILKO mouse livers are more sensitive to LPS-induced liver injury. Consistently, the expression of several proinflammatory cytokines, including Ccl2, Ccl5, and Il1β, was significantly more elevated in FILKO livers after LPS treatments (Figure 7D). These results suggest that autophagy induction in response to endotoxins may play an adaptive role in maintaining homeostasis in hepatocytes and protecting the liver from damages caused by gut-derived endotoxins.

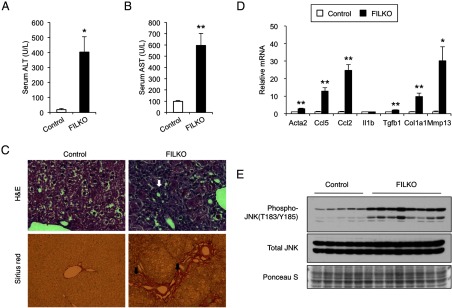

FIP200 deficiency leads to progressive liver injury, fibrosis, and inflammation

To investigate the role of chronic autophagy deficiency in the liver in NASH pathogenesis, we measured plasma ALT and AST concentrations in HFD-fed control and FILKO mice to assess liver injury. Compared with control, plasma ALT and AST levels were elevated by approximately 22- and 6-fold in FILKO mice, respectively (Figure 8, A and B). Elevated liver enzyme levels in FILKO mouse plasma were accompanied by increased infiltration of immune cells and liver fibrosis (Figure 8C). Sirius Red staining indicated that FILKO mice exhibited abundant collagen deposition in pericellular space with a chicken wire pattern, accompanied by portal-portal bridging fibrosis. Gene expression analyses indicated that mRNA levels of genes involved in inflammation, including Ccl2 and Ccl5, and liver fibrosis, including Acta2, Tgfb1, Col1a1, and Mmp13, were significantly elevated in FILKO mouse livers (Figure 8D). We next examined the phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) at the T183 and Y185 sites, markers of proinflammatory cytokine signaling. We found that, although total JNK protein levels remained similar between the two groups, the levels of phosphorylated JNK were significantly elevated in FILKO mouse livers (Figure 8E). The levels of nitrotyrosine and dityrosine, markers of oxidative stress, were similar between control and FILKO livers (data not shown). We concluded from these studies that autophagy plays a protective role in limiting liver injury and fibrosis in diet-induced metabolic stress.

Figure 8.

Autophagy deficiency results in increased liver injury, inflammation, and hepatic fibrosis in FILKO mice. A and B, Plasma ALT (A) and AST (B) levels in control (white columns) and FILKO (black columns) mice. Data represent mean ± SE. *, P < .05; **, P < .01. C, H&E (top panels) and Sirius Red/Fast Green (bottom panels) staining of liver sections from HFD-fed control and FILKO mice. Arrows indicate immune cell infiltration (top panels) and collagen deposition (bottom panels), respectively. D, qPCR analysis of genes involved in inflammation and fibrosis. Data represent mean ± SE. *, P < .05; **, P < .01. E, Phosphorylation of JNK on T183/Y185 sites in total liver lysates from control and FILKO mice. Total JNK and Ponceau S stain serve as loading controls.

Discussion

Autophagy is emerging as a potentially important pathway in the regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism. Recent studies have demonstrated that lipid droplets are in close contact with autophagosomes and undergo lysosomal hydrolysis to release fatty acids (22). However, whether impaired autophagy per se is the driving force underlying excess fat accumulation in the liver in insulin resistant state has been controversial (22–24). In this study, we demonstrated that hepatocyte-specific autophagy deficiency does not promote hepatic steatosis under physiological conditions and in the context of diet-induced obesity. In contrast, we observed lower liver triglyceride content in FILKO mice after overnight starvation. In addition, diet-induced hepatic steatosis was also ameliorated in the FILKO mouse livers. These findings were similar to a previous study using Atg7 knockout mice in which liver triglyceride content was lower in Atg7 null mouse livers after starvation at postnatal day 22, 8 weeks, and 16 weeks of age (23, 24). In addition, RNA interference knockdown of several autophagy genes in worms also resulted in decreased lipid content (45). Although we cannot formally rule out the possibility that liver injury caused by FIP200 deficiency may contribute to reduced fat accumulation in the liver, other models of liver injury, such as alcohol feeding, actually results in more severe hepatic steatosis. Together these observations suggest that autophagy exerts a profound influence on hepatic lipid metabolism, but it is likely dispensable for mobilizing lipids from lipid droplets for β-oxidation in hepatocytes.

How FIP200 deficiency in hepatocytes results in decreased triglyceride accumulation in the liver remains unknown at present. Measurements of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion using Tyloxapol, a lipase inhibitor, revealed that VLDL secretion rate was decreased in FILKO mice compared with control (data not shown). As such, the reduction of triglyceride content in FILKO mice is unlikely due to enhanced VLDL secretion. Gene expression analyses indicate that FIP200 deletion caused a global inhibition of genes involved in different aspects of lipid metabolism, including de novo lipogenesis, triglyceride synthesis, and fatty acid β-oxidation (Figures 2E and 3E). These observations are consistent with published microarray data on Atg7 conditional knockout mouse livers (46). Analyses of a microarray data set (GSE20415) revealed that the expression of Dgat2, Gpam, Acly, Scd1, Fasn, Cpt1a, Acox1, and Acsl1 was down-regulated in both Atg7-deficient and FILKO mouse livers, suggesting that a common link between autophagy activity and hepatic lipid metabolic gene expression. We noted that the mRNA expression and nuclear protein level of transcription factor SREBP1c was significantly decreased in FILKO mice (Figure 5), which may contribute to reduced de novo lipogenesis and triglyceride synthesis. The decrease of SREBP1c could be a consequence of deficient LXR signaling, supported by the diminished induction of lipogenic genes after LXR agonist treatment in FILKO mice. Together these results suggest that autophagy deficiency exerts profound effects on the expression of genes involved in hepatic lipid metabolism.

Autophagy plays an essential role in the clearance of protein aggregates, damaged organelles, and intracellular pathogens (47). In response to low doses of LPS treatments, the expression of several autophagy genes, and more importantly, autophagy flux were significantly enhanced in the liver (Figure 7, A and B). Autophagy induction by LPS has been previously observed in macrophages and cardiomyocytes (48, 49). Toll-like receptor-4-mediated activation of autophagy facilitates pathogen clearance in macrophages and serves as an important aspect of innate immunity, whereas LPS-induced autophagy is associated with cytoprotection in cardiomyocytes. Hepatocytes are exposed to low concentrations of endotoxins derived from gut microbiota through portal circulation. Increased exposure to gut-derived endotoxins has been proposed to cause liver injury and exacerbate inflammation in NASH. As such, the induction of autophagy gene program and activity by LPS may serve as a homeostatic mechanism to protect the liver from endotoxin-induced damages. In support of this, liver-specific deficiency of FIP200 leads to chronic liver injury associated with fibrosis and inflammation. It is possible that certain genetic and/or environmental factors may result in autophagy inhibition in a subset of patients during NAFLD pathogenesis (21, 50–55). In this case, a chronic deficit of autophagy may sensitize these patients to liver damage, leading to the initiation and/or exacerbation of NASH.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs Alan Saltiel, Daniel Klionsky, Diane Fingar, Ken Inoki, and Elizabeth Speliotes and laboratory members for discussions. We thank Dotty Sorenson and the Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory (University of Michigan) for technical support on the EM study.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK077086 and American Diabetes Association Grant 7–08-CD-14).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ALT

- alanine aminotransferase

- AST

- aspartate aminotransferase

- ATG

- autophagy-related protein

- EM

- electron microscopy

- eWAT

- epididymal white fat

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- HFD

- high-fat diet

- FILKO

- liver-specific FIP200 knockout

- FIP200

- adaptor protein focal adhesion kinase family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa

- H&E

- hematoxylin and eosin

- JNK

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LXR

- liver X receptor

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- NAFLD

- nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

- nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NEFA

- nonesterified fatty acid

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- SREBP1c

- sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c

- SRS

- stimulated Raman scattering

- ULK1

- unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1

- VLDL

- very low-density lipoprotein.

References

- 1. Cohen JC, Horton JD, Hobbs HH. Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science. 2011;332(6037):1519–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. James O, Day C. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: another disease of affluence. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1634–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jornayvaz FR, Samuel VT, Shulman GI. The role of muscle insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of atherogenic dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with the metabolic syndrome. Annu Rev Nutr. 2010;30:273–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Szczepaniak LS, Nurenberg P, Leonard D, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure hepatic triglyceride content: prevalence of hepatic steatosis in the general population. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(2):E462–E468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, et al. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40(6):1387–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loomba R, Sirlin CB, Schwimmer JB, Lavine JE. Advances in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;50(4):1282–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chitturi S, Abeygunasekera S, Farrell GC, et al. NASH and insulin resistance: Insulin hypersecretion and specific association with the insulin resistance syndrome. Hepatology. 2002;35(2):373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55(7):434–438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beaven SW, Tontonoz P. Nuclear receptors in lipid metabolism: targeting the heart of dyslipidemia. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:313–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Postic C, Dentin R, Denechaud PD, Girard J. ChREBP, a transcriptional regulator of glucose and lipid metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:179–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(9):1125–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40(12):1461–1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chalasani N, Guo X, Loomba R, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants associated with histologic features of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Speliotes EK, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Wu J, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variants associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease that have distinct effects on metabolic traits. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(3):e1001324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hebbard L, George J. Animal models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8(1):35–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pagliassotti M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2012;32:17–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Polyzos S, Kountouras J, Zavos C, Deretzi G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: multimodal treatment options for a pathogenetically multiple-hit disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(4):272–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147(4):728–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang Z, Klionsky D. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(9):814–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu HY, Han J, Cao SY, et al. Hepatic autophagy is suppressed in the presence of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: inhibition of FoxO1-dependent expression of key autophagy genes by insulin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(45):31484–31492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang L, Li P, Fu S, Calay E, Hotamisligil G. Defective hepatic autophagy in obesity promotes ER stress and causes insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2010;11(6):467–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, et al. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458(7242):1131–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim KH, Jeong YT, Oh H, et al. Autophagy deficiency leads to protection from obesity and insulin resistance by inducing Fgf21 as a mitokine. Nat Med. 2013;19(1):83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shibata M, Yoshimura K, Furuya N, et al. The MAP1-LC3 conjugation system is involved in lipid droplet formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;382(2):419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Strnad P, Zatloukal K, Stumptner C, Kulaksiz H, Denk H. Mallory-Denk-bodies: lessons from keratin-containing hepatic inclusion bodies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1782(12):764–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zatloukal K, Stumptner C, Fuchsbichler A, et al. p62 Is a common component of cytoplasmic inclusions in protein aggregation diseases. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(1):255–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: definition and pathology. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21(1):3–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Banner BF, Savas L, Zivny J, Tortorelli K, Bonkovsky HL. Ubiquitin as a marker of cell injury in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114(6):860–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caldwell SH, Lee VD, Kleiner DE, et al. NASH and cryptogenic cirrhosis: a histological analysis. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8(4):346–352 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mizushima N. The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22(2):132–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hara T, Takamura A, Kishi C, et al. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181(3):497–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang C, Liang CC, Bian ZC, Zhu Y, Guan JL. FIP200 is required for maintenance and differentiation of postnatal neural stem cells. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(5):532–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wei H, Wei S, Gan B, Peng X, Zou W, Guan JL. Suppression of autophagy by FIP200 deletion inhibits mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Devt. 2011;25(14):1510–1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gan B, Peng X, Nagy T, Alcaraz A, Gu H, Guan J-L. Role of FIP200 in cardiac and liver development and its regulation of TNFα and TSC-mTOR signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. 2006;175(1):121–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li S, Liu C, Li N, et al. Genome-wide coactivation analysis of PGC-1α identifies BAF60a as a regulator of hepatic lipid metabolism. Cell Metab. 2008;8(2):105–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Waguri S, Komatsu M. Biochemical and morphological detection of inclusion bodies in autophagy-deficient mice. In: Klionsky DJ, ed. Methods in Enzymology. Volume 453: Autophagy in Disease and Clinical Applications. Part C San Diego: Academic Press/Elsevier; 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ma D, Li S, Lucas E, Cowell R, Lin J. Neuronal inactivation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) protects mice from diet-induced obesity and leads to degenerative lesions. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(50):39087–39095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Komatsu M, Waguri S, Koike M, et al. Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell. 2007;131(6):1149–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Komatsu M, Kurokawa H, Waguri S, et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(3):213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Antinozzi PA, Berman HK, O'Doherty RM, Newgard CB. Metabolic engineering with recombinant adenoviruses. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:511–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kalaany NY, Mangelsdorf DJ. LXRS and FXR: the yin and yang of cholesterol and fat metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:159–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Lane MD, Clemens M, Diehl AM. Obesity increases sensitivity to endotoxin liver injury: implications for the pathogenesis of steatohepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(6):2557–2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Haspel J, Shaik RS, Ifedigbo E, et al. Characterization of macroautophagic flux in vivo using a leupeptin-based assay. Autophagy. 2011;7(6):629–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ma D, Panda S, Lin J. Temporal orchestration of circadian autophagy rhythm by C/EBPβ. EMBO J. 2011;30(22):4642–4651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lapierre LR, Silvestrini MJ, Nunez L, et al. Autophagy genes are required for normal lipid levels in C. elegans. Autophagy. 2013;9(3):278–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Riley BE, Kaiser SE, Shaler TA, et al. Ubiquitin accumulation in autophagy-deficient mice is dependent on the Nrf2-mediated stress response pathway: a potential role for protein aggregation in autophagic substrate selection. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(3):537–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rubinsztein DC, Codogno P, Levine B. Autophagy modulation as a potential therapeutic target for diverse diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11(9):709–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu Y, Jagannath C, Liu XD, Sharafkhaneh A, Kolodziejska KE, Eissa NT. Toll-like receptor 4 is a sensor for autophagy associated with innate immunity. Immunity. 2007;27(1):135–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yuan H, Perry CN, Huang C, et al. LPS-induced autophagy is mediated by oxidative signaling in cardiomyocytes and is associated with cytoprotection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296(2):H470–4-H79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stappenbeck TS, Rioux JD, Mizoguchi A, et al. Crohn disease: a current perspective on genetics, autophagy and immunity. Autophagy. 2011;7(4):355–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Songane M, Kleinnijenhuis J, Alisjahbana B, et al. Polymorphisms in autophagy genes and susceptibility to tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e41618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Koga H, Kaushik S, Cuervo A. Altered lipid content inhibits autophagic vesicular fusion. FASEB J. 2010;24(8):3052–3065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. King KY, Lew JD, Ha NP, et al. Polymorphic allele of human IRGM1 is associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis in African Americans. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Choy A, Dancourt J, Mugo B, et al. The Legionella effector RavZ inhibits host autophagy through irreversible Atg8 deconjugation. Science. 2012;338(6110):1072–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cemma M, Brumell JH. Interactions of pathogenic bacteria with autophagy systems. Curr Biol. 2012;22(13):R540–R545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]