Abstract

Relapse to cocaine seeking is associated with potentiated excitatory synapses in nucleus accumbens. α2δ-1 is an auxiliary subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels that affects calcium-channel trafficking and kinetics, initiates extracellular signaling cascades, and promotes excitatory synaptogenesis. Previous data demonstrate that repeated exposure to alcohol, nicotine, methamphetamine, and morphine upregulates α2δ-1 in reward-related brain regions, but it was unclear whether this alteration generalized to cocaine. Here, we show that α2δ-1 protein was increased in nucleus accumbens after cocaine self-administration and extinction compared with saline controls. Furthermore, the endogenous ligand thrombospondin-1, responsible for the synaptogenic properties of the α2δ-1 receptor, was likewise elevated. Using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of EPSCs in nucleus accumbens, we demonstrated that gabapentin, a specific α2δ-1 antagonist, preferentially reduced the amplitude and increased the paired-pulse ratio of EPSCs evoked by electrical stimulation in slices from cocaine-experienced rats compared with controls. In vivo, gabapentin microinjected in the nucleus accumbens core attenuated cocaine-primed but not cue-induced reinstatement. Importantly, gabapentin's effects on drug seeking were not due to a general depression of spontaneous or cocaine-induced locomotor activity. Moreover, gabapentin had no effect on reinstatement of sucrose seeking. These data indicate that α2δ-1 contributes specifically to cocaine-reinstated drug seeking, and identifies this protein as a target for the development of cocaine relapse medications. These results also inform ongoing discussion in the literature regarding efficacy of gabapentin as a candidate addiction therapy.

Keywords: α2δ-1, cocaine self-administration, gabapentin, nucleus accumbens, relapse, thrombospondin

Introduction

Even after prolonged abstinence, drug users experience high rates of relapse (Dennis and Scott, 2007). Pathological alterations in physiological and structural plasticity mediated by enduring changes in glutamatergic transmission are key features underlying vulnerability to relapse (Kalivas, 2009; Wolf, 2010; Gipson et al, 2013). Hence, investigation of mechanisms responsible for this plasticity represents a priority of preclinical research. Voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) control neurotransmitter release, influence neuronal excitability, regulate gene transcription, and participate in multiple forms of short-term plasticity, underscoring their importance in regulating normal neurotransmission (Kawamoto et al., 2012). Moreover, VGCCs have been implicated in drug-related plasticity and behavior. Repeated noncontingent cocaine administration increases voltage-sensitive calcium currents in response to membrane depolarization in medial prefrontal cortex, an effect reversed by an L-type calcium channel (LTCC) antagonist (Nasif et al., 2005); and the development and expression of cocaine locomotor sensitization is dependent on VGCC function (Pierce et al., 1998; Schierberl et al., 2011).

VGCCs are heteromeric complexes comprised of a pore-forming α1 subunit with ancillary β, α2δ, and γ subunits (Dolphin, 2012). α2δ-1 modulates VGCC kinetic properties, including inactivation rate, in addition to regulating channel trafficking and stability (Dolphin, 2012). Moreover, α2δ-1 subunits perform calcium-independent functions, including intracellular or extracellular signaling and excitatory synaptogenesis. While a number of reports have examined the involvement of individual α1 subunits to drug-induced plasticity and reward, much less is known about the contributions of accessory subunits. Repeated, noncontingent treatment with nicotine, ethanol, and methamphetamine increases α2δ-1 in cerebral cortex (Hayashida et al., 2005; Katsura et al., 2006; Kurokawa et al., 2011). Preliminary results from a proteomic screen indicate that α2δ-1 is upregulated in NAc postsynpatic density (PSD)-enriched subfraction from cocaine self-administering animals, compared with saline controls, raising the possibility that α2δ-1 is also regulated by cocaine and by both contingent and noncontingent drug administration (Reissner et al., 2011).

Gabapentin (GBP, Neurontin), an antiepileptic approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, is a high-affinity ligand for α2δ-1 (Gee et al., 1996). Chronic gabapentin reduces calcium currents via inhibition of α2δ-1 membrane trafficking, its purported primary mechanism of action in neuropathic pain. Effects of acutely applied gabapentin on calcium currents are more equivocal with some reports of inhibition and others showing no effect (Uchitel et al., 2010). Gabapentin acting on presynaptic α2δ-1-containing VGCCs reduces the release of many neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, explaining its indirect effects on GABAergic transmission and misleading nomenclature (Uchitel et al., 2010). Moreover, gabapentin directly antagonizes thrombospondin (TSP)-mediated excitatory synapse formation (Eroglu et al., 2009). Astrocyte-secreted TSP proteins are endogenous ligands for α2δ-1 whose binding promotes excitatory synapse formation independent of calcium-channel activity (Eroglu et al., 2009). The present study sought to verify the proteomic identification of upregulated α2δ-1 as a consequence of cocaine self-administration, and uses gabapentin as a selective α2δ-1 antagonist in NAc core (NAcore) to demonstrate functional involvement of upregulated α2δ-1 in cocaine reinstatement and cocaine-induced cellular adaptations.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Single-housed male Sprague Dawley rats (225–250 g) purchased from Charles River Laboratories were acclimated to facilities 1 week before surgery. Subjects were kept on a 12 h reverse light/dark cycle. Standard chow and water was provided ad libitum before self-administration; however, food was restricted to ∼20 g/d throughout behavioral testing. Procedures were preapproved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Medical University of South Carolina and performed in compliance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Surgery.

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine HCl (87.5 mg/kg of Ketaset, Fort Dodge Animal Health)/xylazine (5 mg/kg Rompum, Bayer) and implanted with intrajugular catheters and 26 gauge bilateral guide cannulas (Plastics One) in NAcore: +1.5 mm anteroposterior, +2.0 mm mediolateral, −5.0 mm dorsoventral (Paxinos and Watson, 2005). Ketorolac (3 mg/kg) was given postoperatively for analgesia. Prophylactic antibiotic (cefazolin 10 mg/0.1 ml, i.v.) was administered during surgery and 5 d postoperatively.

Self-administration.

Catheters were flushed daily with heparin to maintain patency. Rats acquired operant responding for food pellets in one 15 h overnight session on a fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule before beginning 2 h daily self-administration sessions. Rats self-administered cocaine until reaching a criterion of 10 d ≥10 infusions (0.2 mg/0.05 ml), followed by 2 weeks extinction as described previously (Reissner et al., 2011). Training was performed in standard operant chambers containing a house light, drug-paired tone and cue light, and two retractable levers (Med Associates). Yoked-saline controls received a saline infusion for each cocaine infusion. During extinction, active lever presses no longer resulted in delivery of cocaine or cues. Cue-induced reinstatement entailed the drug-free reintroduction of previously drug-paired light/tone cues contingent upon lever pressing. Cocaine-primed reinstatement was precipitated by a 10 mg/kg intraperitoneal cocaine injection without cues.

Western blotting.

Animals were rapidly decapitated and tissue samples microdissected for sample preparation. PSD subcellular fractionation samples were homogenized with 0.32 m sucrose, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, and protease/phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The PSD was isolated as a Triton X-100-insoluble fraction as described previously (Reissner et al., 2011). Whole-cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer supplemented with 1% SDS and inhibitors. Immunoblotting was performed according to standard protocols (Reissner et al., 2011). Primary antibodies were used as follows: α2δ-1 (Sigma-Aldrich #D219; 1:2000), ADAMTS1 (Abcam #39194; 1:1000), TSP-1 (Dr. Dean Mosher, University of Wisconsin–Madison; 1:500), GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology #2118; 1:5000).

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings.

NAcore medium spiny neurons (MSNs) were whole-cell patch clamped as described before (Kupchik et al., 2012). Briefly, acute coronal brain slices were prepared using a Leica VT1200S vibratome (Leica Microsystems) and kept in room temperature aCSF (in mm: 126 NaCl, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 11 glucose, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.4 CaCl2, 2.5 KCl, 2.0 Na-pyruvate, 0.4 L-ascorbic acid, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2) containing 5 mm kynurenic acid and 50 μm d-(-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid until recording. Recordings were performed at 32°C (TC-344B; Warner Instrument) in dorsomedial NAcore using glass microelectrodes (1–2 MΩ) containing (in mm) 124 cesium methanesulfonate, 10 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid potassium, 1 ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 1 MgCl2, 10 NaCl, 2 magnesium adenosine triphosphate, 1 QX-314, pH 7.2–7.3, 272–275 mOsm. EPSCs were evoked with a bipolar stimulating electrode (FHC) ∼200 μm dorsomedial to recording electrode, amplified by a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices), and recorded using Axograph software (Axograph Scientific). Each trace consisted of two identical stimulations 50 ms apart to provide the paired-pulse ratio (PPR). Recordings were collected every 30 s. GABA-evoked inhibitory currents were blocked by 50 μm picrotoxin. Series resistance (Rs) was monitored with a −2 mV test pulse and recordings with unstable Rs (20% change) or Rs > 20 MΩ were discarded.

Sucrose self-administration and reinstatement.

The parameters for sucrose self-administration were similar to those for cocaine. Rats learned to respond for sucrose pellets paired with light and tone cues on progressively increasing schedules (FR1, FR2, FR5) until they stabilized their responding on a FR5 schedule. Rats then entered 2 weeks extinction wherein lever pressing had no consequence. During reinstatement, subjects received two pellets immediately on session initiation and an additional 10 pellets at 2 min intervals for the first 20 min of the session. Lever presses resulted in cue but not sucrose delivery.

Microinjections and histology.

Gabapentin (Sigma-Aldrich) or aCSF was microinjected into NAcore (2 mm below the guide cannula base) before reinstatement. Microinjection (0.5 μl total volume) occurred over a 2 min period followed by 2 min diffusion time. Reinstatement was initiated after 10 min delay. Rats were tested in a random, crossover design separated by 2–3 d of extinction for both within-subject and between-subjects comparisons. For histology, animals were overdosed with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and transcardially perfused with 1× PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Coronal sections (100 μm) were stained with cresyl violet to validate cannula placement.

Locomotor activity.

Rats were placed in a photocell apparatus to record movement using software that estimated distance traveled based on consecutive breaking of adjacent photobeams for 60 min to assess effects of gabapentin on exploratory/basal locomotor activity (AccuScan Instruments). Effects of gabapentin on cocaine-induced activity (10 mg/kg, i.p.) were assessed after 1 h habituation to chambers. Rats received microinjections of gabapentin/aCSF into NAcore immediately before placement in photocell chambers.

Statistics.

Electrophysiological and behavioral data were analyzed by ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni's or Dunnet's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. When only two groups were compared, as in Western blotting, statistical probability was determined by two-tailed Student's t test. Between-subjects analysis was conducted for cue-induced reinstatement due to ordering effect.

Results

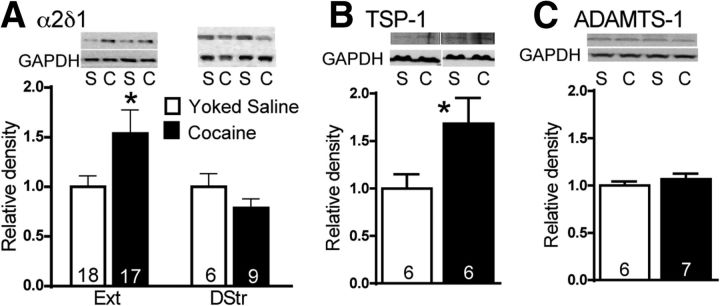

α2δ-1 Protein is upregulated after cocaine self-administration

We performed Western blotting on a membrane-enriched fraction and whole-cell lysates from NAcore comparing rats after cocaine self-administration and extinction with saline controls to validate a suggested increase in calcium-channel subunit α2δ-1 from a proteomic screen (Reissner et al., 2011). α2δ-1 levels were greater in cocaine-extinguished rats than in controls in NAcore (Fig. 1A; t(33) = 2.087, *p = 0.045). We examined α2δ-1 in dorsal striatum because of concerns that microinjected GBP might diffuse back up the cannula track into dorsal striatum in our behavioral assays, but found no difference between cocaine and yoked-saline animals (Fig. 1A) nor any effect of GBP on reinstated cocaine seeking when directly administered dorsal to NAcore (see Fig. 4). We concurrently assessed whether cocaine experience affected the levels of TSP-1, an endogenous secreted ligand for α2δ-1, and found an increase in TSP-1 after self-administration and extinction (Fig. 1B; t(10) = 2.214, *p = 0.05). Given the potential importance of post-translational processing of TSP-1, we assessed levels of ADAMTS1 (A disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospodin type 1 motifs), which cleaves TSP-1, releasing the C-terminal tails from the trimeric N-terminal domain (Lee et al., 2006), but observed no change in ADAMTS-1 levels (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Cocaine self-administration upregulates α2δ-1. A, α2δ-1 is increased after cocaine self-administration (C) compared with saline (S) in PSD subfractions and whole-cell lysates (left). α2δ-1 was unchanged in the dorsal striatum at this time point (right). B, TSP-1 was elevated after extinction from cocaine self-administration compared with saline. C, ADAMTS-1 was unaltered by cocaine self-administration. Data shown as relative density to yoked-saline values, and N is shown in the bars.

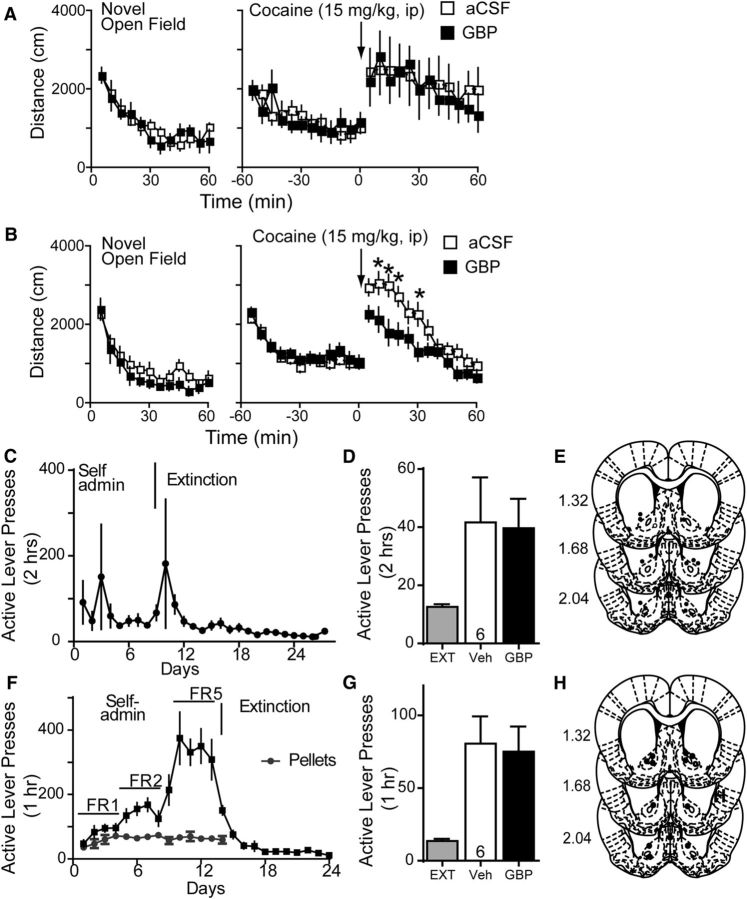

Figure 4.

Gabapentin control experiments. A, 10 μg/side microinjection of gabapentin did not alter basal locomotor activity or cocaine-induced hyperactivity (10 mg/kg, i.p., cocaine injection at arrow). B, 33 μg/side GBP did not alter basal locomotor activity but blunted cocaine-induced hyperactivity. C, Active lever pressing during self-administration and extinction training for cocaine reinstatement in D. D, Microinjection of GBP (10 μg/side) in dorsal striatum has no effect on cocaine-induced reinstatement. E, Histological verification of injection placement in dorsal striatum corresponding to data in D; numbers refer to millimeters rostral to bregma. F, Active lever pressing during self-administration and extinction training for sucrose reinstatement in G. G, Microinjection of GBP (10 μg/side) in NAcore had no effect on sucrose pellet plus cue-primed reinstatement of sucrose seeking. H, Histological verification of injection placement in NAcore corresponding to data in G. *p < 0.05, comparing GBP with aCSF microinjection using a Bonferroni's post hoc analysis.

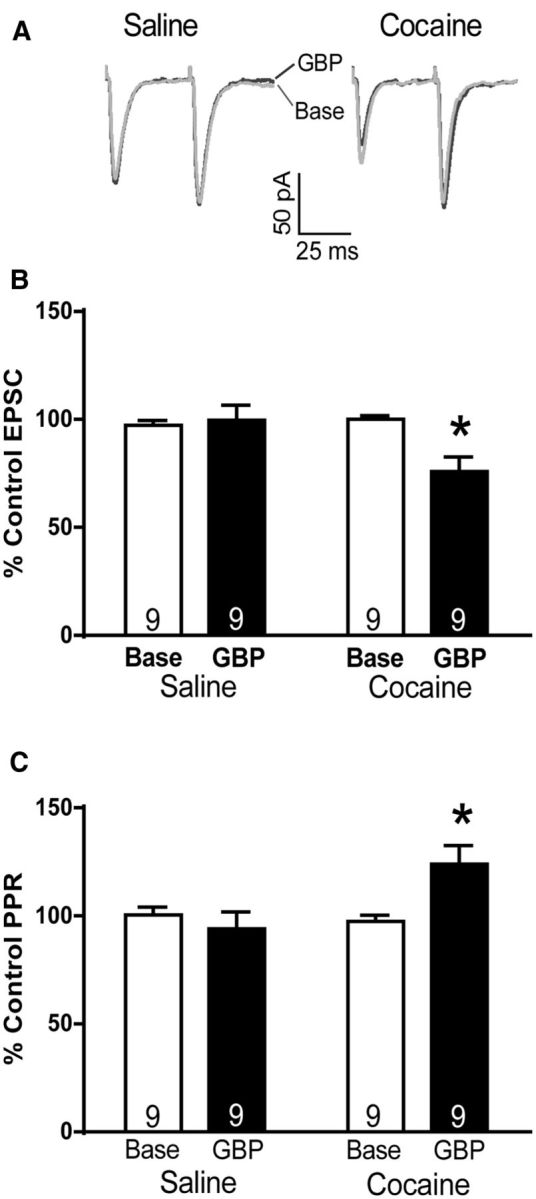

Gabapentin reduced evoked EPSC amplitude and increased PPR

To examine the effects of gabapentin on cocaine-induced synaptic plasticity, we performed whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of NAcore MSNs from cocaine-extinguished and yoked-saline rats. Bath application of 50 μm gabapentin decreased evoked EPSC amplitude normalized as a percentage of pregabapentin baseline amplitude in cocaine but not saline rats (Fig. 2A,B; paired Student's, t(8) = 3.38, p < 0.001). These data are consistent with a functional increase in α2δ-1 protein after cocaine self-administration and extinction. Additionally, gabapentin increased the PPR in cocaine rats (Fig. 2A,C; paired Student's, t(8) = 2.83, p = 0.022), suggesting presynaptic inhibition of glutamate release.

Figure 2.

Gabapentin reduces evoked EPSC amplitude and increases PPR. A, Representative traces of evoked EPSC recorded from NAcore MSNs of yoked-saline (left) and cocaine-extinguished (right) rats before and after washing with 50 μm gabapentin. B, Gabapentin decreased EPSCs only in cocaine-extinguished rats. C, Gabapentin increased PPR only in cocaine-extinguished rats. *p < 0.05, comparing effect of GBP with baseline.

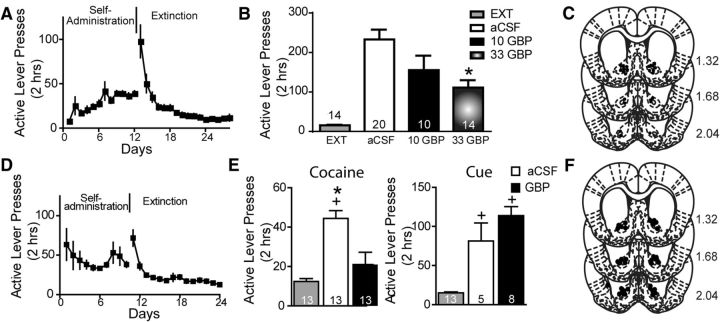

Gabapentin inhibited cocaine-primed but not cue-induced reinstatement

Next we examined whether pharmacological antagonism of the α2δ-1 subunit with gabapentin affects cocaine reinstatement. Rats were trained to self-administer cocaine to criterion (∼12 d), then extinguished for an additional 12–16 d (Fig. 3A). Initial studies using dual cocaine plus cue-primed reinstatement showed a dose-dependent effect of gabapentin on reinstatement response (Fig. 3B; one-way ANOVA with repeated measures, F(3,58) = 22.43, p < 0.001; Fig. 3C, guide cannula placements). Importantly, the lower 10 μg gabapentin dose did not modify basal locomotor activity or the acute locomotor stimulating effects of cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.; Fig. 4A). The 33 μg gabapentin dose showed no effect on baseline locomotor activity; however, it significantly attenuated cocaine-induced locomotor activity, necessitating the use of the 10 μg dose in subsequent experiments (Fig. 4B; repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, interaction F(23,460) = 3.67, p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Gabapentin attenuates cocaine-induced reinstatement. A, Active lever pressing during self-administration and extinction training corresponding to data in B. B, Microinjection of gabapentin into the NAcore dose-dependently reduced cocaine plus cue reinstatement compared with vehicle. EXT, Average active lever presses over the 2 d of extinction before each reinstatement trial. C, Histological verification of injection sites corresponding to data in B; numbers are millimeters rostral to bregma. D, Active lever pressing during self-administration and extinction training corresponding to data in E. E, Gabapentin (10 μg/side) significantly reduced cocaine-primed reinstatement (left) but had no impact on cue-induced reinstatement (right). F, Histological verification of injection sites corresponding to data in E. +p < 0.05 compared with extinction levels of active lever pressing using a Bonferroni's post hoc analysis. *p < 0.05, comparing aCSF to gabapentin.

Because divergent neuronal mechanisms may underlie the distinct modalities of reinstatement (cue-induced vs drug-primed; Shaham et al., 2003; Epstein et al., 2006), we used a separate cohort of rats to query gabapentin's effects on each form of reinstatement independently. Rats similarly underwent cocaine self-administration and extinction (Fig. 3D). Using the previously validated 10 μg dose, we found that gabapentin significantly decreased cocaine seeking elicited by a noncontingent cocaine priming injection (Fig. 3E, left; one-way ANOVA with repeated measures, F(2,23) = 22.55, p < 0.001). In contrast, gabapentin was ineffective at altering cue-induced reinstatement (Fig. 3E, right; one-way ANOVA between subjects, F(2,23) = 32.55, p < 0.001; Fig. 3F, guide cannula placements). When one or both of the injector tips was located outside of the NAcore, generally just dorsal to the boundary, the effect of gabapentin on cocaine-primed reinstatement was lost (Fig. 4C–E). Importantly, in sucrose self-administration controls, gabapentin likewise had no effect on pellet plus cue-primed reinstatement (Fig. 4F–H).

Discussion

Here we show that VGCC α2δ-1 subunit is elevated in NAcore after cocaine self-administration and extinction. While we cannot rule out an influence by extinction training, the two other studies found elevated α2δ-1 at 24 h after a final noncontingent daily drug injection (methamphetamine or nicotine), suggesting that the increase may not depend on extinction training or a withdrawal period (Hayashida et al., 2005; Kurokawa et al., 2011). In agreement with elevated α2δ-1 levels, cocaine-extinguished rats were more sensitive to the EPSC-inhibiting effects of gabapentin. Additionally, the levels of α2δ-1 ligand TSP-1 were increased after cocaine. When α2δ-1 was acutely antagonized with gabapentin, there was a decrease in cocaine-primed reinstatement with no effect on reinstatement of a natural reward, sucrose. These results point to a pivotal role for elevated α2δ-1 in cocaine-reinstated drug seeking, an animal model of relapse (Shaham et al., 2003).

This is the first report directly targeting drug-induced α2δ-1 in a brain region critical to reward during reinstatement. Notably, the possibility that altered α2δ-1 function is a shared neuropathology in addiction is indicated by the fact that it is increased by chronic noncontingent treatment with other classes of addictive drug (Hayashida et al., 2005; Kurokawa et al., 2011). α2δ-1 Interacts with multiple subtypes of voltage-sensitive calcium channels, including presynaptic release-regulating N-type and P/Q-type channels, as well as with postsynaptic L-type channels, which have been implicated in animal models of addiction (Rajadhyaksha and Kosofsky, 2005; Dolphin, 2012). In association with presynaptic VGCCs, α2δ-1-inhibiting gabapentinoid drugs decrease evoked release of many neurotransmitters, including glutamate and dopamine (Reimann, 1983; Quintero et al., 2011). Corticoaccumbens glutamate transmission is increased during reinstated cocaine seeking (Kalivas, 2009), and the GBP-induced decrease in eEPSCs and increase in PPR in NAcore MSNs of cocaine animals supports this presynaptic mechanism. Alternatively, GBP also reduces dopamine release (Reimann, 1983), and inactivation of the VTA or systemic delivery of dopamine antagonists prevents cocaine-induced reinstatement and associated synaptic plasticity (Shen et al., 2014). A predominant influence on dopamine rather than glutamate release could explain gabapentin's preferential effects on cocaine or cocaine plus cue-primed reinstatement compared with conditioned cues as a noncontingent cocaine injection causes greater release of dopamine compared with cue (Ito et al., 2000).

Despite the above-mentioned evidence, we cannot discount the possible contribution of dendritically expressed α2δ-1 coupling to primarily postsynaptic LTCCs. Several studies have linked LTCC-mediated signaling to cocaine-induced changes in AMPA receptor plasticity observed in NAc that are essential for cocaine-induced reinstatement (Pierce et al., 1998; Anderson et al., 2008). Thus, increased α2δ-1 in concert with LTCCs may contribute to the dynamic excitability of NAc neurons whereby the intrinsic membrane excitability is decreased at early withdrawal, restored after protracted withdrawal, and ultimately augmented upon re-exposure to cocaine (Mu et al., 2010). Finally, calcium channel-independent mechanisms may play a role in gabapentin's effects since α2δ-1 stimulation by TSPs promotes the formation of excitatory synapses (Eroglu et al., 2009). Withdrawal from chronic cocaine is associated with LTP-like increases in dendritic spine density and diameter with a further LTP-like augmentation of synaptic strength accompanying reinstated cocaine seeking (Gipson et al, 2013; Shen et al., 2014). Therefore gabapentin's inhibition of TSP/α2δ-1-mediated excitatory synaptogenesis may contribute to its ability to reduce cocaine reinstatement, although the LTP-like changes occur after reinstatement elicited by either cues or cocaine injection. While our finding elevated TSP-1 in NAcore of cocaine-trained subjects is consistent with this possibility, it is also worth noting that TSP-1 catabolic products can interact directly with integrins independent of binding α2δ-1. A peptide modulator used to disrupt this interaction also inhibits cocaine-induced, but not cue-induced, reinstatement of cocaine seeking (Wiggins et al., 2011). This supports an involvement of TSP-1 binding to integrins.

In accord with our present findings, Kurokawa et al. showed that intracerebroventricular delivery of gabapentin blocks methamphetamine-induced sensitization and conditioned place preference (2011), but other studies have examined the effects of a single systemic injection of gabapentin on cocaine self-administration or cocaine-primed reinstatement with negative results (Filip et al., 2007; Peng et al., 2008). The differing effects in these studies may be related to the poor bioavailability of systemic GBP to the brain (Bockbrader et al., 2010). This is supported by reductions in cocaine seeking elicited by conditioned cues and pharmacological stressors after systemic administration of another α2δ-1 antagonist, pregabalin, with improved bioavailability (de Guglielmo et al., 2013). Perhaps due to these bioavailability issues, GBP has had mixed results in clinical addiction studies as well (Minozzi et al., 2008; Mason et al., 2009, 2012). Our study highlights the potential importance of cocaine-induced alterations in α2δ-1 in NAcore, and the efficacy of GBP on only cocaine-induced reinstatement suggests that its utility in controlling cocaine relapse will be in combination with other treatments.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH Grant DA015369/DA003906 (P.W.K.). R.M.B. was supported by the American Australian Association. The authors thank members of the Kalivas laboratory for helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Anderson SM, Famous KR, Sadri-Vakili G, Kumaresan V, Schmidt HD, Bass CE, Terwilliger EF, Cha JH, Pierce RC. CaMKII: a biochemical bridge linking accumbens dopamine and glutamate systems in cocaine seeking. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:344–353. doi: 10.1038/nn2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, Chapel S, Janiczek N, Burger P. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:661–669. doi: 10.2165/11536200-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Guglielmo G, Cippitelli A, Somaini L, Gerra G, Li H, Stopponi S, Ubaldi M, Kallupi M, Ciccocioppo R. Pregabalin reduces cocaine self-administration and relapse to cocaine seeking in the rat. Addict Biol. 2013;18:644–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Scott CK. Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2007;4:45–55. doi: 10.1151/ascp074145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC. Calcium channel auxiliary α2δ and β subunits: trafficking and one step beyond. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:542–555. doi: 10.1038/nrn3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Preston KL, Stewart J, Shaham Y. Toward a model of drug relapse: an assessment of the validity of the reinstatement procedure. Psychopharmacology. 2006;189:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu C, Allen NJ, Susman MW, O'Rourke NA, Park CY, Ozkan E, Chakraborty C, Mulinyawe SB, Annis DS, Huberman AD, Green EM, Lawler J, Dolmetsch R, Garcia KC, Smith SJ, Luo ZD, Rosenthal A, Mosher DF, Barres BA. Gabapentin receptor α2δ-1 is a neuronal thrombospondin receptor responsible for excitatory CNS synaptogenesis. Cell. 2009;139:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M, Frankowska M, Zaniewska M, Gołda A, Przegaliński E, Vetulani J. Diverse effects of GABA-mimetic drugs on cocaine-evoked self-administration and discriminative stimulus effects in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;192:17–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee NS, Brown JP, Dissanayake VU, Offord J, Thurlow R, Woodruff GN. The novel anticonvulsant drug, gabapentin (Neurontin), binds to the subunit of a calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5768–5776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson CD, Kupchik YM, Shen H, Reissner KJ, Thomas CA, Kalivas PW. Relapse induced by cues predicting cocaine depends on rapid, transient synaptic potentiation. Neuron. 2013;77:867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashida S, Katsura M, Torigoe F, Tsujimura A, Ohkuma S. Increased expression of L-type high voltage-gated calcium channel α1 and α2/δ subunits in mouse brain after chronic nicotine administration. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;135:280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito R, Dalley JW, Howes SR, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Dissociation in conditioned dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens core and shell in response to cocaine cues and during cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7489–7495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07489.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW. The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:561–572. doi: 10.1038/nrn2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsura M, Shibasaki M, Hayashida S, Torigoe F, Tsujimura A, Ohkuma S. Increase in expression of alpha1 and alpha2/delta1 subunits of L-type high voltage-gated calcium channels after sustained ethanol exposure in cerebral cortical neurons. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;102:221–230. doi: 10.1254/jphs.FP0060781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto EM, Vivar C, Camandola S. Physiology and pathology of calcium signaling in the brain. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:61. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupchik YM, Moussawi K, Tang XC, Wang X, Kalivas BC, Kolokithas R, Ogburn KB, Kalivas PW. The effect of N-acetylcysteine in the nucleus accumbens on neurotransmission and relapse to cocaine. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:978–986. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa K, Shibasaki M, Mizuno K, Ohkuma S. Gabapentin blocks methamphetamine-induced sensitization and conditioned place preference via inhibition of α2/δ-1 subunits of the voltage-gated calcium channels. Neuroscience. 2011;176:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NV, Sato M, Annis DS, Loo JA, Wu L, Mosher DF, Iruela-Arispe ML. ADAMTS1 mediates the release of antiangiogenic polypeptides from TSP1 and 2. EMBO J. 2006;25:5270–5283. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason BJ, Light JM, Williams LD, Drobes DJ. Proof-of-concept human laboratory study for protracted abstinence in alcohol dependence: effects of gabapentin. Addict Biol. 2009;14:73–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason BJ, Crean R, Goodell V, Light JM, Quello S, Shadan F, Buffkins K, Kyle M, Adusumalli M, Begovic A, Rao S. A proof-of-concept randomized controlled study of gabapentin: effects on cannabis use, withdrawal and executive function deficits in cannabis-dependent adults. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1689–1698. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minozzi S, Amato L, Davoli M, Farrell MF, Lima Reisser AA, Pani PP, Silva de Lima M, Soares B, Vecchi S. Anticonvulsants for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16:CD006754. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006754.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu P, Moyer JT, Ishikawa M, Zhang Y, Panksepp J, Sorg BA, Schlüter OM, Dong Y. Exposure to cocaine dynamically regulates the intrinsic membrane excitability of nucleus accumbens neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3689–3699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4063-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasif FJ, Hu XT, White FJ. Repeated cocaine administration increases voltage-sensitive calcium currents in response to membrane depolarization in medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3674–3679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0010-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Peng XQ, Li X, Li J, Ramachandran PV, Gagare PD, Pratihar D, Ashby CR, Jr, Gardner EL, Xi ZX. Effects of gabapentin on cocaine self-administration, cocaine-triggered relapse and cocaine-enhanced nucleus accumbens dopamine in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Quick EA, Reeder DC, Morgan ZR, Kalivas PW. Calcium-mediated second messengers modulate the expression of behavioral sensitization to cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:1171–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero JE, Dooley DJ, Pomerleau F, Huettl P, Gerhardt GA. Amperometric measurement of glutamate release modulation by gabapentin and pregabalin in rat neocortical slices: role of voltage-sensitive Ca2+ α2δ-1 subunit. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:240–245. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.178384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajadhyaksha AM, Kosofsky BE. Psychostimulants, L-type calcium channels, kinases, and phosphatases. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:494–502. doi: 10.1177/1073858405278236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann W. Inhibition by GABA, baclofen and gabapentin of dopamine release from rabbit caudate nucleus: are there common or different sites of action? Eur J Pharmacology. 1983;94:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissner KJ, Uys JD, Schwacke JH, Comte-Walters S, Rutherford-Bethard JL, Dunn TE, Blumer JB, Schey KL, Kalivas PW. AKAP signaling in reinstated cocaine seeking revealed by iTRAQ proteomic analysis. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5648–5658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3452-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schierberl K, Hao J, Tropea TF, Ra S, Giordano TP, Xu Q, Garraway SM, Hofmann F, Moosmang S, Striessnig J, Inturrisi CE, Rajadhyaksha AM. Cav1.2 L-type Ca2+ channels mediate cocaine-induced GluA1 trafficking in the nucleus accumbens, a long-term adaptation dependent on ventral tegmental area cav1.3 channels. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13562–13575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2315-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, De Wit H, Stewart J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HW, Gipson CD, Huits M, Kalivas PW. Prelimbic cortex and ventral tegmental area modulate synaptic plasticity differentially in nucleus accumbens during cocaine-reinstated drug seeking. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:1169–1177. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchitel OD, Di Guilmi MN, Urbano FJ, Gonzalez-Inchauspe C. Acute modulation of calcium currents and synaptic transmission by gabapentinoids. Channels. 2010;4:490–496. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.6.12864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins A, Smith RJ, Shen HW, Kalivas PW. Integrins modulate relapse to cocaine-seeking. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16177–16184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3816-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME. The Bermuda Triangle of cocaine-induced neuroadaptations. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]