Abstract

Optimism is a cognitive construct (expectancies regarding future outcomes) that also relates to motivation: optimistic people exert effort, whereas pessimistic people disengage from effort. Study of optimism began largely in health contexts, finding positive associations between optimism and markers of better psychological and physical health. Physical health effects likely occur through differences in both health-promoting behaviors and physiological concomitants of coping. Recently, the scientific study of optimism has extended to the realm of social relations: new evidence indicates that optimists have better social connections, partly because they work harder at them. In this review, we examine the myriad ways this trait can benefit an individual, and our current understanding of the biological basis of optimism.

Keywords: Motivation, optimism, pessimism, expectancies, health, coping

Introduction to Dispositional Optimism

The personality dimension optimism versus pessimism has roots both in folk wisdom and in over a century of expectancy-incentive motive theories. Contemporary research into the correlates of this trait began nearly 30 years ago with the creation of the Life Orientation Test, a self-report measure of optimism, which was revised in 1994 [1] to focus its item content more closely on expectancies for one’s future, the trait’s conceptual core. Optimism is one of a family of related constructs, including hope [2], attributional style [3], and self-efficacy [4]. It differs from those partly by being focused on positive versus negative expectations for the future without regard to the means by which such outcomes occur (you can, for example, be optimistic because you have great confidence in your abilities or because you believe other people like and look out for you). It differs from situational expectancies in terms of the range of situations to which the expectancy is applicable and its stability over time.

Although it is possible to disparage this construct as merely folk psychology, optimism turns out to be a case in which widespread intuition has a strong basis in reality. The optimism construct has proven to be useful and relevant to a wide range of topic areas, and this review addresses work in several of them. Given current interest among cognitive scientists in links between motivation and cognition (e.g., a special issue of Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience is in preparation addressing these links), examination of this cognitive-affective construct, which has important motivational overtones, seems timely.

Variations in personality have never been popular as predictors in the cognitive sciences. In part this is probably because the desire to make causal statements precludes reliance on correlational variables. The fact that personality is quite an important determinant of many kinds of behavior, however [5], suggests that it may deserve a closer look. The fact that optimism is a facet of personality that is inherently cognitive in nature (i.e., expectancies about the future) may make it especially appealing.

This review has some boundaries that should be noted at the outset. The term optimism is used in diverse ways in various contexts, and not all of them are reviewed here. This review does not discuss contextualized (goal-specific) optimism [6], which can behave quite differently from generalized optimism under some circumstances [7]. It does not discuss so-called unrealistic optimism [8], the idea that people on the whole expect better outcomes than are realistically justified (but see [9] for a critique of this view and [10] for evidence that the phenomenon is distinct from trait optimism). The review focuses on research in which optimism is assessed by face-valid self-reports, holding aside research in which optimism is inferred from patterns of causal explanation [11], in part because the measures used in the two literatures are not strongly correlated [12]. It is also noted that use of the labels “optimist” and “pessimist” is for convenience in description; most research examines the construct as a continuous distribution (though see Box 1 for an unresolved issue in that regard).

Box 1. One Dimension or Two?

Some personality dimensions are bipolar, others are unipolar. The logic behind the optimism construct assumes a bipolar dimension, with “substance” at each end and a neutral point in the middle. There has been controversy, however, about whether optimism is a bipolar dimension or there are two separable dimensions, one pertaining to affirmation versus disavowal of optimism, the other to affirmation versus disavowal of pessimism.

This issue arises because responses to optimistically framed items (e.g., “I’m always optimistic about my future”) and responses to pessimistically framed items (e.g., “I hardly ever expect things to go my way”) generally form two factors. Some people think this means there are two substantive dimensions; others think the split is a product of method variance in responding. Sometimes separating those item subsets has led to better prediction of other outcomes from one or the other subset, but other times there has been no benefit. A number of studies aimed at settling the issue have reached opposite conclusions: some that a unidimensional view is best [e.g., 78–80], others that there are two dimensions that should be treated separately [e.g., 81–82]. This issue, which remains unresolved, actually pertains to virtually all bipolar trait scales, which typically form two factors if the scales contain subsets of items affirming both poles.

For the sake of simplicity, in this article we treat optimism–pessimism as one dimension. It should be kept in mind, however, that in some studies the extent to which people endorse versus reject a pessimistic outlook was what mattered most; in other studies the extent to which people endorse versus reject an optimistic outlook was what matters most. In yet other studies, this issue did not matter at all. Those who use the scale are encouraged to continue to examine the item subsets as well as the overall scale score, to gain further information on the issue.

Locating Optimism in the Broad Matrix of Personality

Research on optimism began in the mid-1980s, before the 5-factor model of personality structure became the default frame of reference when discussing traits. The 5-factor model [13] distills personality to five broad traits: neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and what is generally labeled openness to experience. It has been suggested that optimism represents a blend of neuroticism and extraversion [14]. Later work, however, tends to support the view that optimism is distinct from those traits [15, 16], while also having some overlap with agreeableness and conscientiousness [17]. In sum, it is not easy to capture optimism well within 5-factor viewpoint.

Trait psychologists have always been contentious about how best to slice up personality, and disagreements have abounded over whether one way or another is fundamental. One might think of the five factors as forming domains of content—the “what” of human motives (extraversion as social influence, neuroticism as threat avoidance, agreeableness as social bonds). One might think of the optimism dimension as part of the “how” of human motives: how goals are turned into behavior (or fail to be turned into behavior) from an expectancy-based viewpoint.

As a practical matter, researchers using the optimism construct have largely ignored the issue of overlap with other traits, though they sometimes do include other traits for comparison with optimism in predictive power; optimism tends to hold up well in such comparisons [18–20]. Those studying optimism generally have instead simply developed their hypotheses within the framework of the expectancy-incentive motivational viewpoint, in which confidence is an important determinant of effort toward goals. That is how the construct is discussed here.

Optimism Research Reflects Broader Views of Self-Regulation

The general approach to self-regulation on which this operationalization of optimism rests [21] assumes that much of life concerns the approach of goals. Expectancies become important primarily when impediments appear. If the person is confident about eventual success, effort continues. If the person is doubtful, there is a tendency to disengage effort. Sometimes disengagement of effort accompanies continued engagement with the goal, yielding distress. Sometimes the disengagement is from the goal itself, resulting in failure to attain it. Optimism versus pessimism reflects such expectancies on a broad scale.

Given the optimism construct’s origins in a broad view of motivation, it is natural that research has investigated its role in motivation-relevant outcomes in various life situations. Optimism has been linked to a greater likelihood of completing college [22]. One study found no association with first-semester law-school grades [23], but another found that optimism during the first semester of law school predicted higher salaries a decade later [24]. One interpretation of this pattern is that optimists are no more capable than those who are less optimistic, but are more persistent in their academic and professional efforts over time. This would be consistent with other evidence to be discussed next.

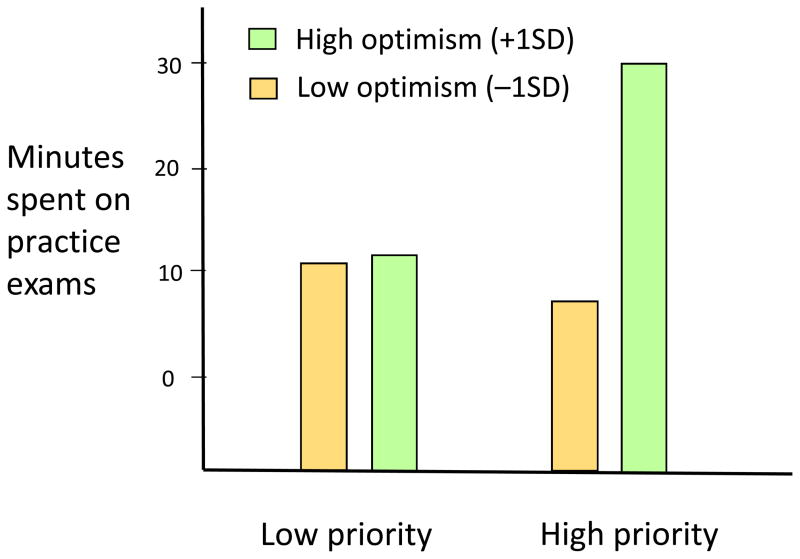

An important characteristic of real life contexts is that people generally pursue multiple goals simultaneously. Research has also examined the role of optimism in outcomes relevant to the juggling of multiple goals. One study found that optimists who were pursuing multiple goals were better at balancing effort expenditures [25]. Another set of studies [26] found that optimists increase goal engagement for high priority goals (and thus are more likely to attain them), and tend to decrease engagement for low priority goals (figure 1). These tendencies occurred in goal domains that included friendship formation, exercise, and scholastic performance. Optimists even display greater engagement in treatment programs (nutrition education and psychotherapy), but only if the need for the program was judged by the person as important [27]. Optimists appear to pick and choose where to invest their self-regulatory resources, increasing efforts when circumstances are favorable (compared to pessimists) and tending to decrease them when circumstances are unfavorable [28]. Indeed, if they believe they are being undermined in the workplace, they report a greater intent to quit than pessimists [29].

Figure 1.

Optimism leads to greater effort toward high-priority goals, but not low-priority goals. Some students (but not others) were given information stressing the importance of doing well on their final course exam, and indicating that preparing for the exam should be a high priority over the next week. Displayed are predicted values of time spent on practice exams as a function of this manipulation, among students at 1 SD above and below the sample mean of optimism. Adapted with permission from the American Psychological Association [26].

Optimism Effects in Relationships

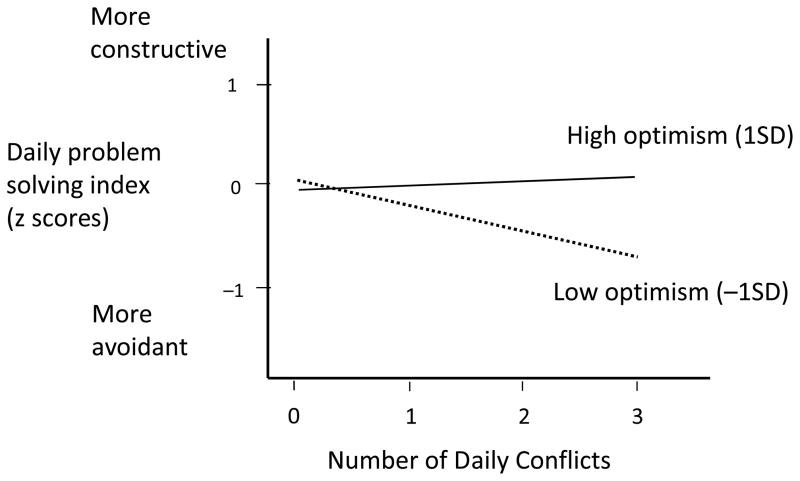

The principles that apply to goal attainment in other domains also can be applied to the management of close relationships. This is a relatively new area of work on optimism. Optimists seem to work harder at relationships [23, 24], consistent with their greater engagement in other high priority tasks. One study of newlyweds [7] found that optimists engaged in more constructive problem solving than pessimists, both in a lab discussion of marital issues with their partner, and outside the lab on days when there was relationship conflict (figure 2). They also had less decline in marital well-being over the first year of their marriage.

Figure 2.

Optimism leads to a greater balance of constructive compared to disruptive problem-solving when marital conflicts arise in day to day life. Spouses completed 12 daily checklists of relationship conflict; they also reported how they had responded to any conflicts that occurred, on 2 items reflecting constructive/positive responses and 2 reflecting negative/avoidant behaviors. An index was formed by subtracting negative from positive responses. Displayed are predicted values (standardized) of that index at values 1 SD above and below the sample mean of optimism, on days of low to higher conflict between partners. Adapted with permission from the American Psychological Association [7].

Optimists report having greater social support than pessimists [30–32], but there is some indication that it is the perception of support that matters rather than actual provision of support [32]. Optimists thrive in a wide range of social conditions, with the result that optimism is related to greater network size, and to ties with others that cross age, educational, and racial boundaries [33]. There is also evidence that this association works in both directions: having strong social networks can enhance optimism [24]. The social effects of optimism can be far-reaching. In one study, optimism (assessed 10 years previously) predicted greater resilience to developing loneliness late in life [34].

Optimism is associated with a warm and slightly dominant interpersonal style, which among men results in greater relationship satisfaction not just for themselves but also for their wives [35]. A similar effect has been found for caregiver burden among wives of men about to undergo coronary artery bypass surgery [36]. Optimists handle relationship crises more successfully than pessimists [37] and they provide nurturant and involved parenting to their children [19, 38], resulting in better adjustment of the children.

Optimism as Mental Orientation to Experiences

As noted earlier, optimism is the expectation that one’s own outcomes will generally be positive. Indeed, it incorporates a belief that a stressful present can change to become better in the future [39]. It is a viewpoint about what the future will hold. It does not, however, involve being oriented preferentially to the future rather than the present [40].

On the other hand, when optimists do think toward the future, they are able to generate more vivid mental images of positive events than are pessimists, a stronger sense of “pre-experiencing” those events (despite not having more vivid imaginations in general) [41]. Consistent with this, one imaging study has found an association between dispositional optimism and greater activation of a brain area that is associated with imagining positive future events [42].

This frame of mind also has reverberations in the present. Optimists appear to be more able than less optimistic people to mentally disengage from, or inhibit, physical pain [43, 44]. They are more responsive to suggestion about pain relief in the form of placebos [45]. In contrast, more pessimistic people are inclined to catastrophize pain experiences, thereby making the experiences subjectively worse [46, 47]. Illness burden, assessed by medical evaluations, promotes greater anxiety among persons low in optimism, but not among those high in optimism [48].

If life turns seriously sour, as reflected in lack of connection with others and perceiving that one has become a burden on others, suicidal ideation emerges among persons low in optimism, but not among those higher in optimism [49]. More generally, optimism reduces the magnitude of the association between rumination and suicidal ideation [50]. Given the adversity of an extended lack of employment, optimists manage to maintain higher life satisfaction, mediated partly by perceptions of family support [51] Optimists report more finding of benefits in adversity than pessimists [52], and there is evidence that this difference is mediated by differences in problem focused coping [53, 54].

Optimism and Health

As noted earlier, research using the optimism construct began at the interface between personality psychology and health psychology. Given this, much of the work on optimism has taken place in health-related contexts, as people confront the transitions imposed by health crises. The early work largely addressed the question of whether optimists fare better emotionally and psychologically than pessimists when confronting health problems, and confirmed that the answer is yes [55]. More recently, however, research has addressed the question of whether optimism also predicts physical health [56]. Many of these studies take the form of epidemiological research, looking at long-term prospective associations between optimism and health outcomes in large samples.

Some of this research examined health outcomes per se. As an example, one major study of cardiovascular disease, using data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), examined quality of life, chronic disease, morbidity, and mortality among over 95,000 women across an 8-year period [18]. All of the women were free of cardiovascular disease and cancer at study entry. Optimists were less likely than pessimists to develop coronary heart disease (CHD), were less likely to die from CHD-related causes, and had lower total mortality due to all causes, across the 8 years of study. Other studies have found that optimism was protective against stroke [57] and against increase in carotid artery blockage over a three-year span [58], and that optimists were less likely to be rehospitalized by 8 months following coronary bypass surgery [59]. It is noteworthy that all of these effects remained even when depressive symptoms were controlled. Thus, despite the fact that pessimism is a symptom of depression, pessimism is not merely depression under another name.

Other studies have examined health markers that might be thought of as physiological pathways to health problems. Optimism has been linked to lower levels of two markers of inflammation [60], to better antioxidant levels [61], to better lipid profiles [62], and to lower cortisol responses under stress [63]. There is also evidence that optimistic children show more adaptive sleep profiles [64]. The latter study used the Parent-rated Life Orientation Test [65] to assess optimism in 8-year-olds. It is noteworthy that associations between optimism and markers of good health appear so early in life (see also Box 2).

Box 2. Origins of optimism and pessimism.

Where do individual differences in optimism and pessimism come from? There clearly is some sort of genetic involvement in this trait. Heritability estimates hover around 30%, depending on the study and the algorithm used to estimate heritability [83–85]. A family/pedigree paradigm has also yielded associations between optimism levels of parents and offspring in two separate cohorts [86]. More recently, evidence has been found that associations between optimism and longevity may also have genetic underpinnings [87].

Researchers have been trying (with mixed success) to identify specific genomic elements that might underlie variations in optimism and pessimism. One study [88] implicated the oxytocin receptor gene (rs53576), but this finding failed to replicate in another study [89]. A haplotype for the mineralocorticoid receptor gene, which helps to regulate stress arousal, has also been related to optimism in one study, but only among men [72]. The only published genome-wide study to date [90] failed to identify any correlate of optimism.

On the environmental side, early childhood experience has also been linked to adult optimism. This research [91] measured optimism in a cohort of adults aged 24 to 27. The researchers also had access to socioeconomic status (SES) of the participants’ families during their early childhood (ages 3 to 6) as well as the participants’ current SES. Childhood SES predicted optimism in adulthood, even after controlling for adult SES.

An apparently unexamined possibility is whether optimism is cultivated directly through parental transmission (e.g., through parental modeling). Another possibility is that optimism could arise via instruction from parents to children on the use of adaptive coping strategies. Use of such strategies might lead to coping successes, thereby laying the foundation for future optimism. It would be useful to explore these possibilities, as well, in future research.

Research has also examined differences in immune response. There is evidence of stronger immune responses among optimists [66, 67] but also evidence of lower immune responses among optimists under conditions of very high challenge [68]. Segerstrom [68] argues that the reduction under high challenge reflects greater behavioral engagement with the challenge, which induces suppression of immune responses in order to conserve energy for the behavior.

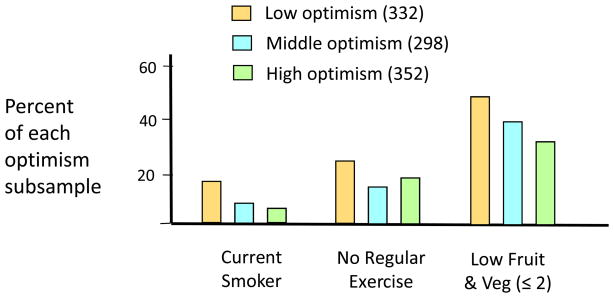

Why do optimists have better health outcomes than pessimists? Two possibilities stand out. One is motivational and behavioral. Part of remaining healthy is doing the right things and avoiding the wrong things. Optimists take a proactive approach to health promotion. They are less likely to smoke, more likely to exercise, have more healthy diets, and are more likely to improve their diets than pessimists [18, 61, 69–71]. [figure 3] These behavioral pathways are all very consistent with the motivated goal pursuit that optimists display in other domains, as reviewed earlier.

Figure 3.

Optimism is associated with more health promoting and less health impairing behavior. They are less likely to smoke, more likely to exercise, and have more healthy diets than pessimists in the form of higher fruit and vegetable consumption (displayed are percentages who reported 2 or fewer servings per day). Adapted with permission from the American Psychosomatic Society [61].

Another reason for better health follows from the better profile of emotional responses to adversity displayed by optimists (less distress, more positive emotions). This pattern of overall emotional experiences, which follows in part from the coping reactions that optimists use [55], doubtlessly results in lower physiological strain over time, resulting in better health [72, 73].

Is Optimism Ever Bad?

A question that has been raised virtually from the inception of research on the optimism construct is whether there are circumstances in which optimism is undesirable. Are optimists ever worse off than pessimists? A common proposal is that a very bad outcome disconfirms an optimist’s expectations so badly that the experience may be worse for the optimist than for a pessimist, who expected a bad outcome and had the expectation confirmed. Although this is a plausible argument, we know of no evidence that supports it. Rather, as noted earlier, optimists endorse the belief that a stressful present can change to a better future [39]. Put differently, the view that “things are bad now, but they will get better” promotes better functioning than “things are bad now and they are going to stay that way.”

There are, however, rare findings of adverse effects of optimism. Two recent findings come from contexts in which too much confidence and persistence might create problems. One is gambling. Research on gambling has found that optimists had more positive expectations for gambling than pessimists, and were less likely to reduce their betting after poor outcomes [74]. Participants in that research were not people with actual gambling problems. But the outcome suggests the possibility of a vulnerability to such problems.

In another recent study, lower levels of optimism among entrepreneurs (in combination with relatively high entrepreneurial experience) predicted better performance in new ventures, defined as employment growth and revenue [75]. This study, however, had an unusual sample: entrepreneurs, who (as the authors pointed out) are especially optimistic as a group. The fact that less optimism predicted better outcomes in a subset of that sample led those authors to suggest that optimism may have curvilinear effects in some contexts. Despite the infrequency of such reversals (and the abundance of positive associations between optimism and motivational outcomes), this possibility warrants study.

Becoming More Optimistic

Given that optimism is beneficial in many life domains, a reasonable question is how to become more optimistic. Recent research has found that two weeks of daily 5-minute sessions of imagining one’s best possible self can increase optimism, at least temporarily [76]. Others have trained people to systematically make more optimistic explanations for events [3]. Indeed, it might be argued that the broad range of cognitive-behavioral therapies used in clinical practice for conditions such as depression [77] typically involve efforts to induce people to approach their lives in more optimistic ways.

Still, optimism is a personality trait. Without manipulation, it generally remains relatively stable over extended periods, at least in the absence of major life transitions [55]. This raises questions about whether procedures such as mental simulations can be expected to have pervasive or long-lasting effects. (Indeed, questions about longevity and pervasiveness can also be raised about formal therapies.) Changing a person’s overall outlook on life can be done, but it is not a simple matter.

Implications and Concluding Remarks

The recent research reviewed here extends previous work in several directions: to consider more closely the role of optimism in prioritization of goals, to consider how optimists handle the demands of close relationships, and to examine how optimism relates to diverse markers of physical well being. The vast majority of the evidence, both old and new, suggests that optimism is a desirable property to have. Clearly there are gaps in knowledge (see Box 3). Research will continue to explore the possibility that optimism is problematic in certain domains, for example, and some work should test for curvilinear effects to determine more clearly what happens at the very highest levels of optimism. Quite likely investigations of optimism and health will continue, with an emphasis on exploration of mechanisms of action.

Box 3. Outstanding Questions.

Is presence of optimism different from absence of pessimism?

Do effects of optimism overlap or differ from effects of other personal strengths?

What are the origins of optimism?

What neural processes subserve optimism?

What biobehavioral mechanisms underlie optimism effects on health?

What techniques might foster change from pessimism to optimism?

How hard is it to change from a relative pessimist to a relative optimist?

Under what circumstances might it be bad to be too optimistic?

Optimism is a construct that illustrates the importance of recognizing that cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes are intertwined. At its center, optimism is a cognitive construct, an expectancy. But by virtue of its connotations of valence (expecting either good or bad), this dimension also has emotional overtones. Finally, the evidence reviewed here makes clear that this expectancy has motivational implications as well. It seems impossible to untangle these threads from each other, and it seems wise to recognize their inextricability.

Highlights.

Greater optimism predicts greater career success

Greater optimism predicts better social relations

Greater optimism predicts better health

All these effects appear to reflect greater engagement in pursuit of desired goals

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this review was supported by a grant from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (AT007262).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Charles S. Carver, University of Miami

Michael F. Scheier, Carnegie Mellon University

References

- 1.Scheier MF, et al. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snyder CR. The psychology of hope: You can get there from here. Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seligman MEP. Learned optimism. Knopf; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts BW, et al. The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychol Sci. 2007;2:313–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armor DA, Taylor SE. Situated optimism: Specific outcome expectancies and self-regulation. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 29. Academic Press; 1998. pp. 209–379. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neff LA, Geers AL. Optimistic expectations in early marriage: A resource or vulnerability for adaptive relationship functioning? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;105:38–60. doi: 10.1037/a0032600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein ND. Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science. 1989;246:1232–1233. doi: 10.1126/science.2686031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris AL, Hahn U. Unrealistic optimism about future life events: A cautionary note. Psychol Rev. 2011;118:135–154. doi: 10.1037/a0020997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein WP, Zajac LE. Imagining a rosy future: The psychology of optimism. In: Markman KD, et al., editors. Handbook of imagination and mental simulation. Psychology Press; 2009. pp. 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson C, Villanova P. An expanded attributional style questionnaire. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:87–89. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsch JK, Conner KR. Dispositional and explanatory style optimism as potential moderators of the relationship between hopelessness and suicidal ideation. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2006;36:661–669. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.6.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Personality trait structure as a human universal. Am Psychol. 1997;52:509–516. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall GN, et al. Distinguishing optimism from pessimism: Relations to fundamental dimensions of mood and personality. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;62:1067–1074. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.62.6.1067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alarcon GM, et al. Great expectations: A meta-analytic examination of optimism and hope. Pers Individ Differ. 2013;54:821–827. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kam C, Meyer JP. Do optimism and pessimism have different relationships with personality dimensions? A re-examination. Pers Individ Differ. 2012;52:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharpe J, et al. Optimism and the big five factors of personality: Beyond neuroticism and extraversion. Pers Individ Differ. 2011;51:946–951. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.07.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tindle HA, et al. Optimism, cynical hostility, and incident coronary heart disease and mortality in the women’s health initiative. Circulation. 2009;120:656–662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinonen K, et al. Parents’ optimism is related to their ratings of their children’s behaviour. Eur J Pers. 2006;20:421–445. doi: 10.1002/per.601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Räikkönen K, Matthews KA. Do dispositional pessimism and optimism predict ambulatory blood pressure during schooldays and nights in adolescents? J Pers. 2008;76:605–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the self-regulation of behavior. Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solberg Nes L, et al. Optimism and college retention: Mediation by motivation, performance, and adjustment. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2009;39:1887–1912. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00508.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rand KL, et al. Hope, but not optimism, predicts academic performance of law students beyond previous academic achievement. J Res Pers. 2011;45:683–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2011.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segerstrom SC. Optimism and resources: Effects on each other and on health over 10 years. J Res Pers. 2007;41:772–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Segerstrom SC, Solberg Nes L. When goals conflict but people prosper: The case of dispositional optimism. J Res Pers. 2006;40:675–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geers AL, et al. Dispositional optimism and engagement: The moderating influence of goal prioritization. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96:913–932. doi: 10.1037/a0014830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geers AL, et al. Dispositional optimism, goals, and engagement in health treatment programs. J Behav Med. 2010;33:123–134. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9238-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pavlova MK, Silbereisen RK. Dispositional optimism fosters opportunity-congruent coping with occupational uncertainty. J Pers. 2013;81:76–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Britton AR, et al. Is the glass really half-full? The reverse-buffering effect of optimism on undermining behavior. Pers Individ Differ. 2012;52:712–717. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srivastava S, et al. Optimism in close relationships: How seeing things in a positive light makes them so. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91:143–153. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Assad KK, et al. Optimism: An enduring resource for romantic relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93:285–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vollmann M, et al. Social support as mediator of the stress buffering effect of optimism: The importance of differentiating the recipients’ and providers’ perspective. Eur J Pers. 2011;25:146–154. doi: 10.1002/per.803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersson MA. Dispositional optimism and the emergence of social network diversity. The Sociological Quarterly. 2012;53:92–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01227.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rius-Ottenheim N, et al. Dispositional optimism and loneliness in older men. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:151–159. doi: 10.1002/gps.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith TW, et al. Optimism and pessimism in social context: An interpersonal perspective on resilience and risk. J Res Pers. 2013;47:553–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruiz JM, et al. Does who you marry matter for your health? Influence of patients’ and spouses’ personality on their partners’ psychological well-being following coronary artery bypass surgery. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91:255–267. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersson MA. Identity crises in love and at work: Dispositional optimism as a durable personal resource. Soc Psychol Quarterly. 2012;75:290–309. doi: 10.1177/0190272512451753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor ZE, et al. Dispositional optimism: A psychological resource for Mexican-origin mothers experiencing economic stress. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26:133–139. doi: 10.1037/a0026755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang EC, et al. An examination of optimism/pessimism and suicide risk in primary care patients: Does belief in a changeable future make a difference? Cognit Ther Res. 2013;37:796–804. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9505-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Busseri MA, et al. Are optimists oriented uniquely toward the future? Investigating dispositional optimism from a temporally-expanded perspective. J Res Pers. 2013;47:533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blackwell SE, et al. Optimism and mental imagery: A possible cognitive marker to promote well-being? Psychiatry Res. 2013;206:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharot T, et al. Neural mechanisms mediating optimism bias. Nature. 2007;450:102–105. doi: 10.1038/nature06280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geers AL, et al. Dispositional optimism and thoughts of well-being determine sensitivity to an experimental pain task. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:304–313. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodin BR, et al. Testing the relation between dispositional optimism and conditioned pain modulation: Does ethnicity matter? J Behav Med. 2013;36:165–174. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9411-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geers AL, et al. Dispositional optimism predicts placebo analgesia. J Pain. 2010;11:1165–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodin BR, et al. The association of greater dispositional optimism with less endogenous pain facilitation is indirectly transmitted through lower levels of pain catastrophizing. J Pain. 2013;14:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanssen MM, et al. Optimism lowers pain: Evidence of the causal status and underlying mechanisms. Pain. 2013;154:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirsch JK, et al. Illness burden and symptoms of anxiety in older adults: Optimism and pessimism as moderators. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1614–1621. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rasmussen KA, Wingate LR. The role of optimism in the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2011;41:137–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tucker RP, et al. Rumination and suicidal ideation: The moderating roles of hope and optimism. Pers Individ Differ. 2013;55:606–611. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duffy RD, et al. Examining a model of life satisfaction among unemployed adults. J Couns Psychol. 2013;60:53–63. doi: 10.1037/a0030771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lechner SC, et al. Curvilinear associations between benefit finding and psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:828–840. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Büyükaşik-Çolak C, et al. Mediating role of coping in the dispositional optimism–posttraumatic growth relation in breast cancer patients. J Psychol: Interdisciplinary and Appl. 2012;146:471–483. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2012.654520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Llewellyn CD, et al. Assessing the psychological predictors of benefit finding in patients with head and neck cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:97–105. doi: 10.1002/pon.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carver CS, et al. Optimism. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:879–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rasmussen HN, et al. Optimism and physical health: A meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:239–256. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9111-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim ES, et al. Dispositional optimism protects older adults from stroke: The health and retirement study. Stroke. 2011;42:2855–2859. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matthews KA, et al. Optimistic attitudes protect against progression of carotid atherosclerosis in healthy middle-aged women. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:640–644. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000139999.99756.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tindle H, et al. Optimism, response to treatment of depression, and rehospitalization after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:200–207. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318244903f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roy B, et al. Association of optimism and pessimism with inflammation and hemostasis in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Psychosom Med. 2010;72:134–140. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cb981b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boehm JK, et al. Association between optimism and serum antioxidants in the Midlife in the United States study. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:2–10. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31827c08a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boehm JK, et al. Relation between optimism and lipids in midlife. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1425–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.01.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jobin J, et al. Associations between dispositional optimism and diurnal cortisol in a community sample: When stress is perceived as higher than normal. Health Psychol. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0032736. ( http://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/hea/index.aspx) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Lemola S, et al. Sleep quantity, quality and optimism in children. J Sleep Res. 2011;20:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lemola S, et al. A new measure for dispositional optimism and pessimism in young children. Eur J Pers. 2010;24:71–84. doi: 10.1002/per.742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kohut ML, et al. Exercise and psychosocial factors modulate immunity to influenza vaccine in elderly individuals. J Gerontol (A Biol Med Sci) 2002;57A:M557–M562. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.9.M557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Szondy M. Optimism and immune functions. Mentalhigiene es Pszichoszomatika. 2004;5:301–320. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Segerstrom SC. How does optimism suppress immunity? Evaluation of three affective pathways. Health Psychol. 2006;25:653–657. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giltay EJ, et al. Lifestyle and dietary correlates of dispositional optimism in men: The Zutphen elderly study. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steptoe A, et al. Dispositional optimism and health behaviour in community-dwelling older people: Associations with healthy ageing. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11:71–84. doi: 10.1348/135910705X42850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hingle M, et al. Optimism and diet quality in the women’s health initiative (WHI) J Acad Nutr Diet. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.12.018. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klok MD, et al. A common and functional mineralocorticoid receptor haplotype enhances optimism and protects against depression in females. Translational Psychiatry. 2011;1:e62. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wrosch C, et al. Goal adjustment capacities, subjective well-being, and physical health. Soc and Pers Psychol Compass. 2013:1–14. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gibson B, Sanbonmatsu DM. Optimism, pessimism, and gambling: The downside of optimism. Pers and Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30:149–160. doi: 10.1177/0146167203259929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hmieleski KM, Baron RA. Entrepreneurs’ optimism and new venture performance: A social cognitive perspective. Acad Management J. 2009;52:473–488. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2009.41330755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Meevissen YMC, et al. Become more optimistic by imagining a best possible self: Effects of a two week intervention. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2011;42:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chiesi F, et al. The accuracy of the life orientation test–revised (LOT-R) in measuring dispositional optimism: Evidence from item response theory analyses. J Pers Assess. 2013;95:523–529. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2013.781029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rauch WA, et al. Method effects due to social desirability as a parsimonious explanation of the deviation from unidimensionality in LOT-R scores. Pers Individ Differ. 2007;42:1597–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Segerstrom SC, et al. Optimism and pessimism dimensions in the Life Orientation Test-Revised: Method and meaning. J Res Pers. 2011;45:126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Glaesmer H, et al. Psychometric properties and population-based norms of the life orientation test revised (LOT-R) Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17:432–445. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rauch WA, et al. An IRT analysis of the personal optimism scale. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2008;24:49–56. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.24.1.49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Plomin R, et al. Optimism, pessimism, and mental health: A twin/adoption analysis. Pers Individ Differ. 1992;13:921–930. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(92)90009-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mosing M, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on optimism and its relationship to mental and self-rated health: A study of aging twins. Behav Genetics. 2009;39:597–604. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mosing MA, et al. Sex differences in the genetic architecture of optimism and health and their interrelation: A study of Australian and Swedish twins. Twin Res Hum Genetics. 2010;13:322–329. doi: 10.1375/twin.13.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rius-Ottenheim N, et al. Parental longevity correlates with offspring’s optimism in two cohorts of community-dwelling older subjects. Age. 2012;34:461–468. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9236-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mosing MA, et al. Genetic influences on life span and its relationship to personality: A 16-year follow-up study of a sample of aging twins. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:16–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182385784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saphire-Bernstein S, et al. Oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is related to psychological resources. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15118–15122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113137108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cornelis MC, et al. Oxytocin receptor (OXTR) is not associated with optimism in the Nurses’ Health Study. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1157–1159. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eriksson N, et al. Web-based, participant-driven studies yield novel genetic associations for common traits. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Heinonen K, et al. Socioeconomic status in childhood and adulthood: Associations with dispositional optimism and pessimism over a 21-year follow-up. J Pers. 2006;74:1111–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]