Abstract

Coronary atherosclerotic plaque rupture is the main cause of myocardial infarction and the leading killer in the US. Inflammation is a known bio-marker of plaque vulnerability and can be assessed non-invasively using FDG-PET imaging. However, cardiac and respiratory motion of the heart makes PET detection of coronary plaque very challenging. Fat surrounding coronary arteries allow the use of MRI to track plaque motion during simultaneous PET-MR examination. In this study, we proposed and assessed the performance of a fat-MR based coronary motion correction technique for improved FDG-PET coronary plaque imaging in simultaneous PET-MR. The proposed methods were evaluated in a realistic four-dimensional PET-MR simulation study obtained by combining patient water-fat separated MRI and XCAT anthropomorphic phantom. Five small lesions were digitally inserted inside the patient coronary vessels to mimic coronary atherosclerotic plaques. The heart of the XCAT phantom was digitally replaced with the patient’s heart. Motion-dependent activity distributions, attenuation maps, and fat MR volumes of the heart, were generated using the XCAT cardiac and respiratory motion fields. A full Monte Carlo simulation using Siemens mMR’s geometry was performed for each motion phase. Cardiac/respiratory motion fields were estimated using non-rigid registration of the transformed fat MR volumes and incorporated directly into the system matrix of PET reconstruction along with motion-dependent attenuation maps. The proposed motion correction method was compared to conventional PET reconstruction techniques such as no motion correction, cardiac gating, and dual cardiac-respiratory gating. Compared to uncorrected reconstructions, fat-MR based motion compensation yielded an average improvement of plaque-to-background contrast (PBC) of 29.6%, 43.7%, 57.2%, and 70.6% for true plaque-to-blood ratios of 10, 15, 20 and 25:1, respectively. Channelized Hotelling Observer (CHO) Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) was used to quantify plaque detectability. CHO-SNR improvement ranged from 105% to 128% for fat MR-based motion correction as compared to no motion correction. Likewise, CHO-SNR improvement ranged from 348% to 396% as compared to both cardiac and dual cardiac-respiratory gating approaches. Based on this study, our approach, a fat-MR based motion correction for coronary plaque PET imaging using simultaneous PET-MR, offers great potential for clinical practice. The ultimate performance and limitation of our approach, however, must be fully evaluated in patient studies.

1. Introduction

Coronary atherosclerotic plaque rupture is responsible for the majority of myocardial infarctions and sudden cardiac deaths. Over a decade ago, it was demonstrated that the risk of experiencing a fatal coronary event does not only depend on atherosclerotic disease extent and severity, but rather on plaque propensity to rupture (the so-called “plaque vulnerability”) which depends on the histology and biological activity of the plaque (Cullen et al 2003).

Vulnerable plaques are typically composed of a lipid-rich core enclosed within a thin layer of tissue (the fibrous cap) largely infiltrated by macrophages. The rupture of the fibrous cap releases a thrombogenic core within the arterial blood flow which can block the blood circulation and cause myocardial infarction. Several studies (Muller et al 1994, Farb et al 1996, Burke et al 1997, Libby et al 2002) have shown the fundamental role of chronic inflammation in the development and rupture of atherosclerotic plaques, and inflammation is now considered as a biomarker strongly associated with likelihood of plaque rupture. While MRI and CT as well as a few invasive techniques, such as intravascular ultrasound, optical coherence tomography, near infrared spectroscopy, and intravascular MRI can assess arterial stenosis and plaque morphology, no direct information can be obtained about the degree of plaque inflammation. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) Positron Emission Tomography (PET) provides a reliable and reproducible measure of glucose metabolic activity, particularly important in activated macrophages during inflammation processes. Previous studies have shown the feasibility of using FDG-PET to measure large vessels (aorta, carotid) inflammation (Rudd et al 2002, Ogawa et al 2004, Tawakol et al 2006, Silvera et al 2009). The correlation between FDG accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques and inflammation level has also been established in both animal models (Tawakol et al 2005) and humans (Blockmans et al 1999, Dunphy et al 2005). Several studies have also reported FDG accumulation in coronary vessels of patients with known or suspected coronary atherosclerotic disease (CAD) (Alexanderson et al 2008, Wykrzykowska et al 2009, Rogers et al 2010). In a recent study, Rogers et al (2010) showed that patients with acute coronary syndromes had higher FDG coronary uptake than patients with stable angina, paving the way towards the use of FDG-PET as a potential technique for detection and evaluation of CAD.

There are considerable technical challenges to overcome for imaging coronary atherosclerotic plaques using PET. First, Partial Volume Effects (PVE), which are caused by limited intrinsic resolution of PET cameras, dramatically reduce measured plaque uptake. Second, the myocardial FDG uptake, which acts as a background signal in which the plaque must be detected, may significantly degrade plaque to background contrast. Third, both cardiac and respiratory motions cause significant blurring in PET images. The PVE can be greatly reduced by modeling Point Spread Functions (PSF) in PET reconstruction. Specific diets altering myocardial metabolism can drastically reduce FDG heart uptake and have been tested for FDG-PET coronary studies (Wykrzykowska et al 2009, Rogers et al 2010). However, correcting the effects of heart motion during the data acquisition still remains a significant challenge to overcome for imaging plaques.

Motion of the heart has two different components given no voluntary patient motion: motion caused by the pumping action of the four chambers (cardiac motion) and the motion caused by respiration. Displacements of 13–23 mm (O’Dell et al 1995, Slomka et al 2004) and 4.9–9 mm (Boucher et al 2004, Blume et al 2010) due to cardiac and respiratory motion, respectively, were reported. One approach to address the motion problem is to perform dual cardiac-respiratory gating (Teräs and Kokki 2010) by only reconstructing the events detected in a specific cardiac/respiratory motion phase. However, gating is not the optimal solution for coronary plaque imaging because rejecting a large number of counts significantly reduces the plaque detection Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) (Delso et al 2011). Instead, PET motion correction, which embeds the motion information within the PET system matrix, allows reconstructing PET images using all detected events while removing motion blurring. In newly available PET-MR scanners, PET and MR data are acquired simultaneously --in contrast to sequential PET/CT- so that information obtained with MRI can be used to improve information content of PET. With high spatial and temporal resolution, MRI is particularly efficient to measure organ motion, which can be in turn incorporated into PET reconstruction, as we demonstrated in preliminary phantoms and animal studies performed on a prototype MR-compatible brain PET scanner for oncologic and cardiac perfusion/viability applications (Guerin et al 2011, Chun et al 2012, Petibon et al 2013). In a recent phantom study from our group (Petibon et al 2013), MR tagging was used to measure myocardial wall motion for subsequent motion correction of the PET data. While tagged-MRI is optimal for measuring myocardial motion, it might not be the most efficient technique to track movements of coronary arteries. Indeed, tagging is efficient when tag lines can impregnate the targeted tissue for a certain amount of time, which is hardly feasible for coronary arteries. Therefore, other MRI techniques have to be specifically designed for coronary arteries tracking, making use of the exceptional versatility of MRI.

Human heart is commonly surrounded by fat, both sub-epicardial fat within the pericardium as well as mediastinal fat outside the pericardium. Heart fat burden have been shown to be associated with the likelihood of having atherosclerosis and various other cardiomyopathies (see Review from Kellman et al 2010) so that significant effort has been undertaken to non-invasively assess heart fat content. Due to the difference in frequencies of resonance between fat and water, MRI is particularly efficient for imaging heart and water-fat separated MR imaging is currently the gold standard for fast, high-resolution imaging of heart fat tissue content. Because coronary vessels are typically enclosed within an adipose matrix, fat MRI can be an efficient way for motion measurement of the coronaries.

In this work, we propose to use fat-MR based motion correction for coronary plaque imaging using simultaneous PET-MR. The estimated motion fields from motion dependent fat MR volumes are incorporated into the system matrix of iterative PET reconstruction, so that all the detected events are reconstructed into a single reference motion phase. The proposed methods are evaluated in a realistic PET-MR study obtained by combining high-resolution heart anatomical information obtained from patient water-fat separated MRI acquisition (performed on a Philips Achieva 1.5 T scanner) and XCAT anthropomorphic phantom torso tissue data (Segars and Tsui 2009). To mimic coronary atherosclerotic plaques, five lesions of sub-resolution size were digitally incorporated within coronary vessels in the patient fat volume. The heart in the XCAT phantom was digitally replaced with the patient’s heart. Motion-dependent activity distribution, attenuation maps, and fat MR volumes were then generated using the XCAT cardiac and respiratory motion fields for 48 different cardiac/respiratory phases. PET Monte Carlo simulations using GATE (Jan et al 2004) and the Siemens Whole-Body (WB) Biograph mMR geometry were performed on the obtained four-dimensional heart and torso tissue data. Cardiac and respiratory motion fields were estimated using non-rigid B-spline registration of fat-MR volumes and incorporated into the system matrix of a sinogram-based OSEM PET iterative reconstruction algorithm, along with motion-dependent attenuation correction factors. The proposed fat-MR based motion correction technique was compared to conventional methods including no motion correction and gating techniques. A plaque detection study using a three dimensional Channelized Hotelling Observer (CHO) was performed to quantify the plaque detectability, providing a comprehensive comparison between the reconstruction methods for the task of PET coronary plaque detection. To the best of our knowledge, such MR-based PET motion correction framework for coronary plaque imaging has not been reported yet in the literature.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Static Patient MRI acquisition

Although we propose to use fat MR to measure motion fields, we chose a patient MR scan using Dixon sequence that included not only a fat MR volume but also a water image volume. The water image volume allows identifying heart and myocardium for PET simulation, as described in Sec. 2.2. The multi-echo Dixon approach for fat and water separation is the standard technique for the assessment of heart fat content in MRI (Goldfarb 2008), Kellman et al 2009, Kellman et al 2010). Dixon’s acquisition methods are based on the difference of resonance frequencies between fat and water. Three-point Dixon sequences (Glover and Schneider 1991) employ three different echo times to obtain three different images: the first two echoes are chosen so that water and fat signal are in-phase and opposed-phase, while the third echo provides information about B0 field inhomogeneity at each voxel, allowing to improve the separation between water and fat signals.

Even though, ultimately, coronary plaque studies will be performed on a whole-body PET-MR scanner, we acquired both fat and water patient MR images on a 1.5T Achieva scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) using a 3D free-breathing and electrocardiogram (ECG)-triggered multi-echo gradient echo (GRE) sequence. The acquisition was used to obtain realistic patient water-fat heart data for subsequent PET simulation. The subject received 0.2 mmol/kg of gadobenate dimeglumine ([Gd-BOPTA] MultiHance; Bracco Imaging SpA, Milan, Italy) and imaging was performed 15 minutes after contrast injection. The sequence parameters were TR=8.0 ms with three echo times TE1/TE2/TE3 =1.53/4.03/6.53 ms, flip angle = 15°, FOV = 270 × 270 × 100 mm3, and spatial resolution of 1.5 × 1.2 × 2 mm [feet-head (FH) × right-left (RL) × anterior-posterior (AP)]. A water selective inversion radiofrequency (RF) pulse, which was tuned to the resonance frequency of water, was applied prior to data acquisition in order to suppress the myocardial signal and improve the fat signal SNR (Havla et al 2012). Respiratory gating and tracking, using a navigator placed on the right hemi-diaphragm with a 5-mm acceptance window, was used. All the raw k-space data were acquired only at the diastolic rest period. The water-fat separation was performed offline using the Iterative Decomposition with Echo Asymmetry and Least-squares (IDEAL) technique (Reeder et al 2004). In this technique, alternate iterations between fat/water signal estimate and field map are used to solve nonlinear signal equations and simultaneously reconstruct fat and water images (Figure 1) along with the field map.

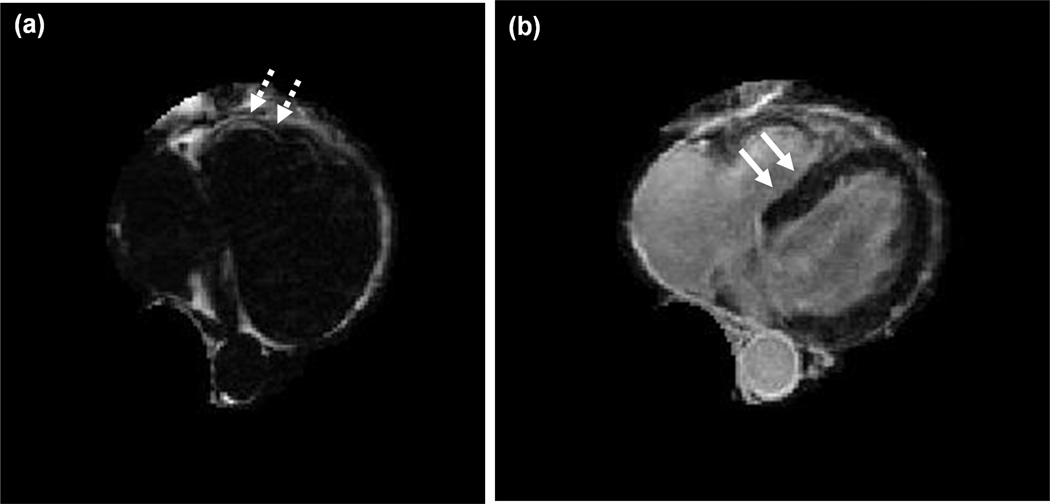

Figure 1.

Same transverse slice through the patient heart displaying (a) fat and (b) water tissue content. Fat/water volumes were obtained using an iterative fat/water separation algorithm (IDEAL). The myocardium is clearly identified in the water volume (plain arrows, right). Adipose tissue surrounding coronary vessels allows identifying coronary vessels within the fat volume (dashed arrows, left).

2.2 Combination of static patient MRI and XCAT numerical phantom

In this research, we took advantage of the patient MR and XCAT numerical phantom to mimic a realistic PET-MR patient study including both cardiac and respiratory motions. More importantly, the true motion field is known, allowing to evaluate the performance of the fat-MR based motion estimation method.

The combination of static patient MRI and four-dimensional XCAT numerical phantom procedure is detailed in the flowchart shown in Figure 2. Heart fat and water volumes were manually segmented within the patient torso using water-fat separated MRI. The myocardium, whose signal was suppressed with a specific inversion pulse during the MR acquisition, was then segmented in the water volume using semi-automatic segmentation algorithm (local intensity thresholding). Five small plaques, P#1-5, were added to different locations inside the coronary vessels as shown in Figure 3. The segmented fat MR volume, in which coronary vessels are well delineated, was used to place the plaques within the patient coronary tree. One plaque was added in the left ascending coronary artery (LAD), two in the left circumflex coronary artery (LCX) and two in the right coronary artery (RCA), all of approximate size ~2.5 × 2.5 × 3.0 mm3 and volumes ranging from 25.9 to 41μL (Table 1). The segmented heart tissue volumes were used to obtain an index image volume in which the myocardium, fat, water and the plaques were assigned to unique integers. XCAT phantom program was then used to generate a torso index image volume with each tissue type assigned to a unique integer. The torso data, comprising the heart and the dome of the liver amongst other organs, was chosen at end-exhalation/end-diastole respiratory/cardiac phase.

Figure 2.

Combination between patient MRI and 4D XCAT phantom.

Figure 3.

3D rendering images of the patient’s fat MRI viewed from two different angles (a) and (b). Five ~2.5 × 2.5 × 3 mm plaques (P#1-5) were added to the coronary vessel walls, which are visible in the fat MR volume. This fat MR volume was deformed into 48 cardiac/respiratory motion phases using the XCAT phantom motion fields.

Table 1.

Plaque volume and location

| Plaque | Volume (μL) | Location |

|---|---|---|

| P#1 | 38.9 | LCX |

| P#2 | 41 | RCA |

| P#3 | 31 | RCA |

| P#4 | 36 | LCX |

| P#5 | 25.9 | LAD |

The static patient heart maps (myocardium, fat, water and plaques) were then inserted inside the XCAT phantom to replace the phantom’s original heart. The patient’s heart water volume was re-oriented and manually aligned with the XCAT heart by matching the respective locations of apex and atrial valves. A scaling factor was found so that both hearts (i.e. XCAT and patient) filled the same total volume. The obtained affine transformation was then applied to all other tissue classes (myocardium, fat and plaques) and the transformed patient heart maps were replaced inside the XCAT torso, in place of the phantom’s original heart.

XCAT program was used to generate both cardiac and respiratory motion fields sampling NCard = 8 cardiac and NResp = 6 respiratory phases, with motion cycles of duration 1 and 5 seconds, respectively. The motion fields were used to transform the index maps into each one of the NF = 48 different cardiac/respiratory phases. The plaques’ displacements due to cardiac contractions and respiration were 0.76–1.15 and 1.82–2.05 cm, respectively, between end-diastole/systole and end-inspiration/end-exhalation, depending on the plaque location within the coronary tree.

2.3 PET simulation

The Monte Carlo simulation software Geant4 Application for Tomography Emission (GATE, Jan et al 2004) was used to simulate PET events using the obtained tissue maps. The simulated scanner was a Siemens Biograph mMR (PET-MR), which consists of 8 rings of 56 blocks of 8x8 lutetium oxyorthosilicate (LSO) crystal detectors of size 4.0 × 4.0 × 20.0 mm3. The inputs to the GATE program include an index image volume (See Sec. 2.2), an activity range file that defines the activity concentration, and an attenuation range file that defines the materials. The range files define the connections between an organ or tissue type and an activity concentration or attenuation coefficient using an index.

For each motion phase, fully 3D and noise-free 18F simulations of each heart tissue class (fat, water, myocardium, plaques) and the rest of the body were performed separately. To speed up the simulation, the torso (excluding the heart) PET simulation was performed only for the 6 different respiratory positions, assuming that the upper body (except heart) is negligibly affected by cardiac motion as compared to respiration. Typical FDG uptake (Table 2) and attenuation coefficients were included in the range files for the simulation of the torso. PET list-mode events for each tissue class and motion phase were binned into sinograms of span 11 (Defrise and Kinahan 1998) with a maximum ring difference of 60, and azimuthal angle interleaving, as is used in the mMR scanner. This data mashing procedure produces sinograms with 344 radial bins, 252 azimuthal angle bins and 837 projection planes. A final gated sinogram at each motion phase (respiratory phase r, cardiac phase c), combining the heart and torso sinograms was then obtained using:

| (1) |

where is a noise-free sinogram corresponding to heart tissue class i at motion phase (r,c), is the noise-free background torso sinogram, a* is a tissue specific sinogram scaling factor and n is additive Poisson noise. The scaling factors were chosen to adjust the total number of counts for the study as well as the myocardium, blood and plaques to background ratios. A total number of 220 million counts was chosen for the whole study, which is typical for a 20 minutes cardiac FDG-PET examination. An activity concentration ratio of 1.3 between the myocardium and the heart blood chamber was chosen, assuming good myocardial signal suppression (Wykrzykowska et al 2009). Following atherosclerotic plaque FDG uptake levels reported in the literature (Tawakol et al 2005), the plaques noise-free sinograms were scaled at levels of 10, 15, 20 and 25 fold with respect to the heart blood level. Plaque absent data (i.e. 1:1 with respect to blood) was also generated for the plaque detection study (see Section 2.6). For each motion phase, NR = 16 noise realizations were generated.

Table 2.

FDG-PET tissue uptake used for the simulation

| Tissue type | FDG concentration |

|---|---|

| Lungs | 0.5 |

| Liver | 3.0 |

| Soft tissue | 1.0 |

| Spine | 2.6 |

| Stomach | 1.5 |

| Blood pool | 1.3 |

| Myocardium | 1.7 |

| Plaques | 10,15,20,25 |

2.4 Motion estimation using fat MRI

As explained in Sec. 2.2, 4D fat MRI volumes were generated by applying XCAT cardiac and respiratory motion fields to the static patient fat-MRI volume acquired at end-exhalation/end-diastole. The obtained gated fat MR volumes were used to compute coronary vessels motion fields using a B-spline deformable registration algorithm as detailed below. Cardiac and respiratory displacements were calculated separately and combined together to compute the motion fields between any cardiac/respiratory phase and the end-diastole/end-exhalation reference phase, as needed for motion corrected PET reconstruction (see section 2.5).

Noting f(k,x) ≡ fr,c(x) a fat MR volume at a given cardiac/respiratory phase k ≡ (r, c), the registration algorithm searches for a 3D cubic B-spline motion field ĝ (k → k′, x) between a pair of volumes f(k, x) and f(k′, x) such that:

| (2) |

where x is the voxel position and N the total number of voxels in one volume. The regularization function R(·) and regularization coefficient γ penalize the differences between adjacent B-spline coefficients of the deformation field to render the motion fields smooth and invertible (Chun et al 2009). To improve the robustness and speed of the registration algorithm, a bi-level multi-resolution strategy was implemented. A first estimate of the motion field is computed on a coarse, sub-sampled image volume and serves as an initial guess for solving the task at the original, finer level, so that the solution is approached by gradual refinements.

First, inter-phase cardiac motion fields were estimated at a given respiratory position by registration of temporally adjacent cardiac gated fat MR volumes using Eq. (2). Likewise, inter-phase respiratory motion fields were estimated by registering consecutive respiratory gated volumes at a single cardiac phase. This procedure is illustrated in Figure 4 (a), where the volumes binned in the matrix’s first column and first row are registered respectively to obtain inter-phase cardiac and respiratory motion fields. Then, the motion fields between each cardiac phase and end-diastole were computed by B-spline composition of inter-phase cardiac motion fields. The exact same procedure was followed for respiratory motion with end-exhalation as the reference phase. Finally, the motion fields between any given respiratory/cardiac phase and the reference end-diastole/end-exhalation were obtained by B-spline composition of the cardiac and respiratory motion fields. In this manner, the complete cardiac/respiratory motion fields were obtained from a single row/column of the matrix. An example of fat-MR motion estimation is shown in Figure 4 (b), in which the gold-standard (XCAT motion fields, green arrows) and estimated fat-MRI (red arrows) motion fields between end-diastole and end-systole are displayed. The estimated motion fields were then incorporated into the PET reconstruction as detailed in the next section.

Figure 4.

Cardiac/respiratory motion estimation using fat-MRI. (a) Illustration of the motion estimation strategy using gated fat-MRI volumes (b) True (green arrows) and estimated fat-MRI motion fields (red arrows) are overlaid on a given fat-MR slice.

2.5 Motion-corrected PET reconstruction

A sinogram-based OSEM iterative PET reconstruction algorithm, modeling the mMR detector block geometry and the fat-MRI based motion fields as well as motion-dependent attenuation correction factors, was developed. This algorithm reconstructs all detected PET events into a reference cardiac and respiratory motion phase. The estimated motion fields were incorporated into the PET system matrix, which has total I sinogram bins and J voxels. The motion-dependent I × J system matrix, whose element represents the probability of a positron emitted in voxel j during motion phase k to be detected along sinogram bin i, is decomposed as:

where Mk is a J × J motion operator that transforms the image at cardiac/respiratory phase k to the reference phase using the estimated motion fields, matrix G is an I × J matrix that models the geometric forward-projection operator [implemented using Siddon’s method (Siddon 1985)], N is an I × I diagonal matrix that contains detector sensitivity normalization coefficients, and Ak is an I × I diagonal matrix that contains motion-dependent attenuation correction factors for phase k. The detector normalization factors N were obtained by GATE simulation of a noise-free 18F filled cylinder occupying the entire scanner’s FOV without modeling the scattering processes. The motion-dependent phantom attenuation maps were obtained by deforming the reference attenuation map into each motion phase using operator Mk. The motion corrected EM reconstruction algorithm is:

| (3) |

where ρ is the column vector of size J containing the activity voxel values in the reference phase, is the column vector of size I containing all the counts detected in cardiac/respiratory phase k, and 1I is a column vector of size I with ones. Angular subsets (OSEM algorithm) were used to speed up convergence of the algorithm. Since each motion phase contributes independently to each iteration, important gain in reconstruction speed can be achieved by computing the contribution of each motion phase in parallel. The parallelization of the reconstruction code was achieved using multi-threading.

For each noise realization, four different reconstruction techniques were considered:

-

-

No Motion Correction: all sinograms were summed together and reconstructed regardless of cardiac/respiratory motion, using a conventional OSEM algorithm.

-

-

Cardiac Gating: only the events detected in the end-diastolic phase (1/8th of the total number of counts) were reconstructed, regardless of respiration.

-

-

Dual Gating (cardiac/respiratory gating): only the events detected in end-diastolic/end-exhalation phase were reconstructed (1/48th of the total number of counts).

-

-

Fat-MR based Motion Correction: all the events were reconstructed using Eq. (3) using the motion fields estimated by fat MR.

All images were reconstructed on a 194 × 194 × 80 voxels grid of size 3.0 × 3.0 × 2.0 mm using 8 iterations and 4 angular subsets.

2.6 Performance evaluation

Plaque to Background Contrast

Plaque to background contrast (PBC) was calculated for all the five plaques and reconstruction methods. First, five 8 × 8 × 8 mm ROIs’ centered on each plaque were defined in the reconstructed PET volumes. Each of these ROIs was then divided into two nested sub-regions: a 3 × 3 × 3 mm ROI centered on the plaque (denoted ROIP and treated as the plaque itself), and a surrounding 5 × 5 × 5 mm ROI shell (denoted ROIb), treated as the background for that particular plaque.

For each noise realization r, the plaque to background contrast was then computed using:

where is the mean activity value in ROI* for noise realization r and M is the total number of voxels within the ROI. The contrast metric was computed as the average pbcr over all noise realizations:

| (4) |

Channelized Hotelling observer

Plaque detectability was assessed using the CHO (Barrett and Myers 2003). The CHO is a linear observer that models the frequency channels present in the human visual system. The SNR of the observer (CHO-SNR metric) was shown to fit well human observer performance in detecting hot lesions within a correlated background (Abbey et al 1996). To compute CHO-SNR, five three-dimensional ROIs of size 15 × 15 × 3 pixels centered on each plaque were defined in the plaque-present PET volumes. The same ROIs were used in the plaque-absent volumes. The CHO-SNR is given by (Kulkarni et al 2007):

| (5) |

where ν̄* = CT[ℑρ̄*] is the mean channel response formed using ℑ the operator extracting the 3D ROIs within the mean plaque-present ρ̄1 and plaque-absent ρ̄0 PET volumes, respectively, and the transpose of the CHO channel template CT. Matrix is the average image co-variance matrix. CHO-SNR was calculated for each plaque, each reconstruction method and plaque uptake. The observer channel template C was formed of three 3D radially symmetric difference-of-Gaussian (DOG) profiles of increasing width parameters (Abbey et al 1996, El Fakhri et al 2011) defined as:

where τ is the spatial frequency, j = 1..3 indexes the channel numbers with width parameter σ02j–1 (σ0 = 0.052).

3. Results

Figure 5 displays the same PET transverse slice reconstructed using the proposed fat-MR based motion correction technique and no motion correction for all four different plaque-to-blood contrast levels (10, 15, 20 and 25:1). In the figure, all the PET intensities were scaled to the same maximum level. On the images without motion correction, the plaques (yellow arrows) are hardly distinguishable from the myocardium for true contrasts of 20-25:1 and become invisible when the true contrast is below 15:1 (yellow dashed arrows). On the other hand, fat-MR based motion correction clearly improves coronary plaque detectability and makes the plaque more distinguishable from its background and the myocardium, for all the contrast levels.

Figure 5.

PET slice reconstructed with and without fat-MR based motion correction for plaque-to-blood activity concentration ratios of 10, 15, 20 and 25. The yellow arrows point to the plaque placed in a coronary vessel directly attached to the myocardium. The fat-MR based motion correction significantly improves plaque detectability as compared to no motion correction.

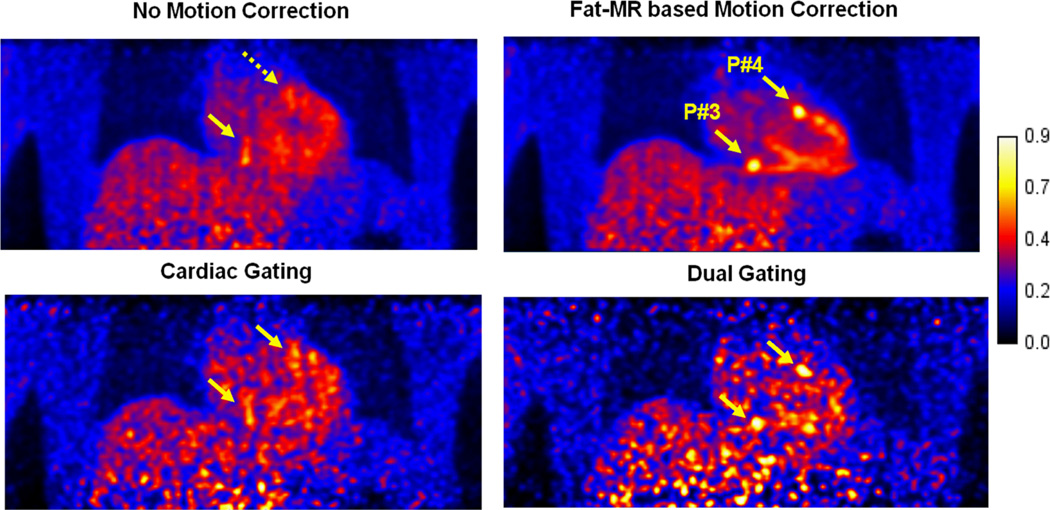

Figure 6 displays the same coronal PET slice through two different plaques (P#3 and P#4) for a true plaque-to-blood activity concentration of 25:1. Both plaques, which are clearly distinguishable if motion correction is applied, would be otherwise invisible. Hardly visible in the uncorrected volume (yellow dashed arrow), cardiac gating allows P4 (directly attached to the myocardium) to be distinguishable, due to removed cardiac motion blurring. Dual gating makes both the plaques visible. The noise level is high for both the gating methods, especially the dual gating method. Fat-MR based motion correction outperforms all the other reconstruction techniques.

Figure 6.

PET slice reconstructed with and without fat-MR based motion correction for plaque-to-blood activity concentration ratios of 25. The yellow arrows point to plaques placed in a coronary vessel directly attached to the myocardium. The fat-MR based motion correction significantly improves plaque detectability as compared to no motion correction.

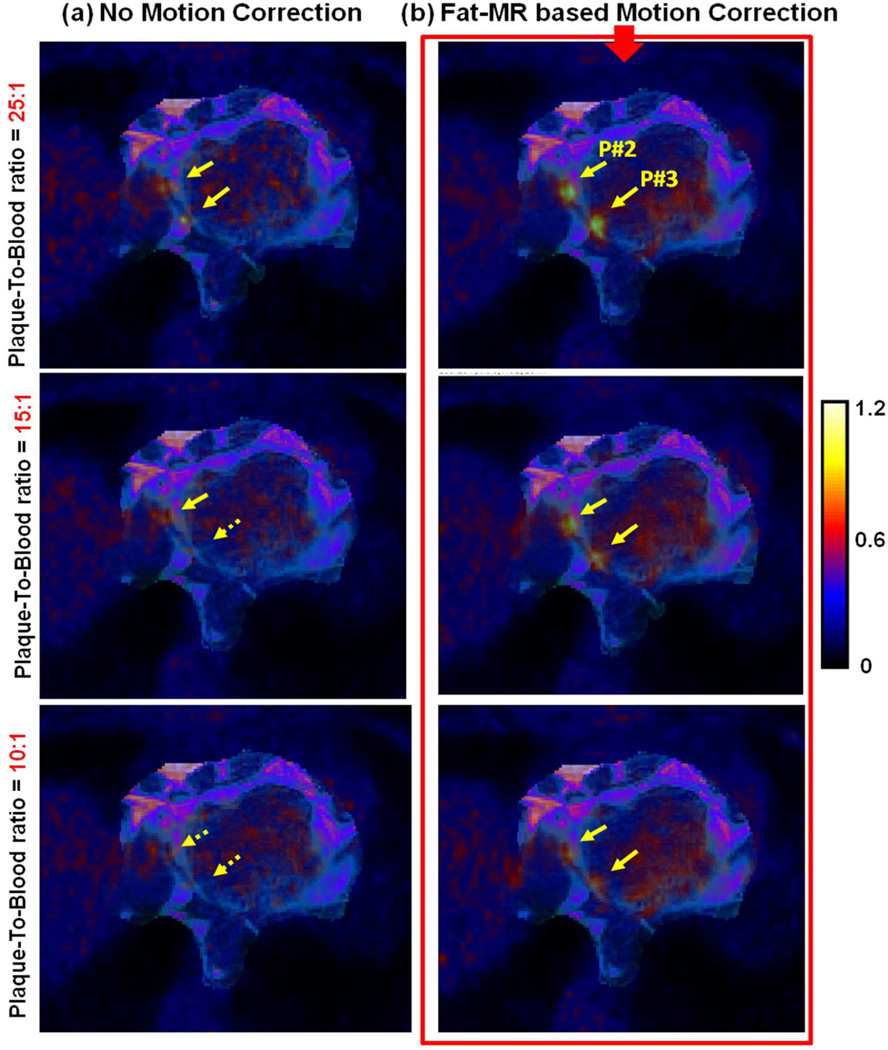

Figure 7 displays a fused transverse PET and fat-MR slice through two different coronary plaques (P#2 and P#3) in the RCA, for three different true plaque-to-blood activity concentration ratios (10, 15, and 25:1). The two plaques are hardly visible in the motion uncorrected images and become invisible below a true contrast of 15:1, due to motion (yellow dashed arrows). As can be seen, fat-MR based motion correction largely improves the plaque contrast as compared to no motion correction. The co-visualization of adipose tissues together with motion corrected PET clearly enhances the visual detectability of such small targets.

Figure 7.

Fused fat-MRI and PET images through two different plaques in the LAD.

Figure 8 displays PBC results computed using Eq. (4) for the five plaques and the four reconstruction methods as a function of true plaque-to-blood activity concentration ratios. The error bars correspond to ±1 standard deviation of plaque contrast metric computed over all noise realizations. Considerably higher error bars are observed when performing dual gating due to increased image noise levels. Cardiac gating noticeably improves PBC as compared to no motion correction for plaques that undergo larger cardiac motion (P#2, P#4). Fat MR-based motion correction significantly improves PBC as compared to no motion correction.

Figure 8.

Plaque-to-blood contrast versus true plaque-to-blood activity concentration ratios.

Figure 9 displays CHO-SNRs computed using Eq. (5) as a function of true plaque-to-blood activity concentration ratios for the five plaques and the four reconstruction methods. Error bars were calculated using the method from (Abbey et al 1997). The fat-MR based motion correction significantly improves plaque detectability as compared to uncorrected and gated reconstructions.

Figure 9.

CHO SNRs versus true plaque-to-blood activity concentration ratios.

4. Discussion

In this study, a PET motion correction technique for coronary plaque imaging in simultaneous PET-MR was proposed and evaluated. Motion fields were estimated using B-spline registration of fat-MRI volumes and incorporated inside a motion corrected PET OSEM algorithm. Significant improvements in terms of plaque contrast recovery and detectability were achieved as compared to conventional reconstruction techniques such as gating and motion uncorrected reconstruction methods.

Vulnerable coronary plaques, whose dimensions are often below the PET camera intrinsic resolution and which undergo large physiologic movements, constitute very challenging targets to image using classical PET techniques. While motion blurring effects may be partly and totally eliminated using cardiac gating and dual gating, respectively, the reduced amount of data (1/8th and 1/48th of the total number of counts, respectively, in this study) dramatically hampers image precision. This is illustrated in Figure 7, in which large uncertainties associated with gated plaque contrasts are found. As shown in Figure 6, cardiac gating slightly improves the contrast of the plaques that are more subject to cardiac motion, such as P#4 that is directly attached to the myocardium, but does not have significant effect on plaques that are more subject to respiratory movement, e.g. P#3. As shown in Figure 9, the motion-uncorrected standard reconstruction method offers better plaque detectability than both gating approaches. This is because cardiac and dual gating only use a fraction of the detected events, causing a large increase in image noise. Although the two plaques are visible using the dual gating approach, it is easier to observe false lesions (false alarm) in the higher noise background (Figure 6). Similar low CHO-SNR levels were observed for both gating techniques. Most likely, the blurring caused by respiratory motion (cardiac gating) compensates the effect of reduced statistics (dual gating) in terms of plaque detectability.

By removing cardiac and respiratory motion blurring while preserving Poisson statistics, the incorporation of fat-MR motion fields within the framework of PET reconstruction was shown to have a significant impact on plaque detectability as compared to uncorrected and gated reconstructions. A clear enhancement of plaque visual detectability for all simulated true plaque-to-blood activity concentration ratios was achieved using this approach as can be seen in Figures 5, 6 and 7. As illustrated in Figure 5, the detection of plaques in the uncorrected volume becomes difficult when plaque true contrast is below 15:1. Motion correction restored signal from plaques otherwise undetectable in the absence of motion correction, especially for the ones directly attached to the myocardium that are more subject to mixing with myocardial activity. Improvements in plaque contrast were in the range of 29.9–71.3% as compared to uncorrected reconstruction (Table 3). CHO-SNR improvements were in the range of 105–128% for motion correction as compared to no motion correction. Likewise, motion correction dramatically improved CHO-SNR by 348–396% as compared to both gating approaches. However, although better plaque contrast and detectability can be achieved using motion correction, accurate coronary plaque uptake quantification is still largely limited by PVE caused by the limited system intrinsic resolution as well as reconstruction algorithms performances. As noted by Jin and colleagues in a recent study (Jin et al 2013), the use of sinogram data mashing (spanning, angle interleaving) necessarily reduces image resolution, as uncertainties are introduced on the exact locations of detected line of responses. In this simulation study, data mashing was performed to match as close as possible to what can be expected in terms of resolution in mMR scanner studies. Data un-spanning procedures or PSF modeling methods may be used to alleviate the effects of data mashing and further improve resolution (Jin et al 2013).

Table 3.

Average plaque contrast and detectability improvement (motion correction vs. no motion correction)

| Plaque-To-Blood ratio | Contrast improvement (%) | CHO-SNR improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 29.6 | 113.4 |

| 15 | 43.7 | 120.0 |

| 20 | 57.2 | 128.7 |

| 25 | 70.6 | 105.2 |

As noted by Rogers et al (2010), one important obstacle for coronary plaque imaging using PET is the lack of anatomical landmarks to confirm that the observed hot spots are indeed derived from coronary plaques. In PET-CT scanners, CT can provide high-resolution anatomical maps, but misalignments between PET and CT data are common since the two modalities are not acquired simultaneously. Additionally, while the PET volume represents an average cardiac/respiratory phase, CT is often acquired using gating (breath-holding and EKG triggering can be used for respiratory and cardiac gating, respectively). Motion corrected PET-MRI allows solving this issue since all PET events are reconstructed within the same reference phase, which allows accurate spatial registration between PET and MR data despite cardiac/respiratory motion. As Figure 7 shows, the co-visualization of motion-corrected PET along with fat MR, in which coronary vessels boundaries are clearly visible, enhances coronary plaque detectability.

Water-fat separated MR imaging using Dixon’s multi-echo methods is the reference technique for assessing heart fat content. The multi-echo Dixon approach has several advantages over conventional chemical shift fat suppression techniques, among which the possibility of acquiring water and fat images simultaneously in a single breath-hold (hence avoiding mis-registration) with fat signal having high SNR and positive contrast (Kellman et al 2009). For PET-MR coronary plaque imaging studies, cardiac water-fat separated MRI may also be used to track coronary vessels during the PET acquisition. The obtained motion information may be subsequently used inside the PET reconstruction to improve PET information content.

As proposed in this study, cardiac and respiratory motion can be measured separately, and a single row and column in the matrix of cardiac and respiratory phases (Figure 4) may be used to obtain the complete cardiac/respiratory motion field. This allows reducing the amount of MRI data to be acquired and subsequently save important imaging time. However, this approach is valid only under the assumption that the heart remains in the exact same position for a given cardiac/respiratory phase. Under free-breathing conditions, as would be the case during PET-MR patient examination, cardiac motion could be measured using an MRI acquisition protocol triggered on EKG R-wave and monitored by navigator-based respiratory rejection in order to collect data only at a specific phase of the respiratory cycle. In the same manner, heart respiratory motion could be measured with an MRI protocol using both EKG R-wave triggering and navigator-based respiratory motion monitoring, in order to collect data at a specific cardiac phase in all the different respiratory phases. Fast FLASH MRI gradient recalled echo sequences with radial encoding of k-lines (Huang et al 2013), which acquire data using multiple echo-time acquisition for offline fat-water signal separation, provide a good compromise in terms of data speed acquisition and image quality. PET events cardiac/respiratory gating can be done using the acquired navigator together with EKG physiological triggering.

The proposed heart motion acquisition strategy, with separate measurements of cardiac and respiratory motions, remains valid if one assumes good reproducibility of both cardiac and respiratory cycles during the acquisition. However, in practice, patient heart beat rate may vary during the acquisition or the heart stroke volume may change according to the respiratory cycle (Magder 2004). These variations will necessarily affect the resolution of the acquired MRI data and the accuracy of the motion field which may not fully characterize the diversity of possible heart motion patterns during the acquisition. This illustrates the tradeoff between MRI acquisition times, that should remain as little as possible, and the quality of the MR-based PET motion correction on the other side.

Future work will be dedicated to evaluate the proposed methods in a cohort of patients after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and intracoronary stent placement. The tissue response to injury following stent placement will cause vessel inflammation which can be imaged with FDG PET-MR. Patients will be imaged less than a week after stent placement. Although it is not the inflammation from the plaque itself, it provides a good model to evaluate our approach because the inflammation can be localized at the vicinity of the stent, which we expect to see on the MR images. Patients will be asked to adhere to a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet the day before the PET-MR examination to suppress myocardial uptake (Wykrzykowska et al 2009, Rogers et al 2010). Patients will be imaged for 25 minutes about three hours after administration of about 15 mCi of FDG. The motion fields will be measured using water-fat separated imaging using the MRI acquisition protocol described above. Important improvements in terms of coronary plaque detectability are expected.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we have proposed and evaluated a fat-MR based PET motion correction method for imaging vulnerable coronary plaque imaging using simultaneous PET-MR. We proposed using fat MRI to track the motion of the coronary vessels and heart during PET-MR acquisition. The proposed methods were evaluated in a realistic 4D PET-MR simulation study obtained by combining high-resolution heart anatomical information obtained from patient water-fat separated MRI and XCAT anthropomorphic phantom torso data. Sub-resolution plaques were digitally added to the coronary vessels. Coronary vessel and heart motion fields, obtained from non-rigid registration of dynamic fat-MRI volumes, were incorporated within the framework of statistical iterative PET reconstruction. The performance of the proposed approach was compared to motion uncorrected, cardiac gating, and dual cardiac/respiratory gating method. By removing cardiac and respiratory motion blurring while preserving Poisson statistics, the proposed approach was shown to largely enhance plaque image quality as compared to uncorrected and gated reconstructions. Dramatic improvements in terms of plaque detectability were observed using the proposed technique. Fat MR based motion correction for coronary plaque PET using PET-MRI has hence great potential in clinical practice. The ultimate performance and limitation of our approach, however, must be derived from patient studies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R21-EB012326, R01-CA165221 and R01-EB008743. The authors would like to thank Dr. Carmella Nappi for her help on the locations of the inserted plaques.

References

- Abbey CK, Barrett HH, Wilson DW. Observer signal-to-noise ratios for the ML-EM algorithm. Proc. SPIE. 1996;2712:47–58. doi: 10.1117/12.236860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey CK, Barrett HH, Wilson DW. Observer signal-to-noise ratios for the ML-EM algorithm. Proc. Soc. Photo. Opt. Instrum. Eng. 1996;2712:47–58. doi: 10.1117/12.236860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexanderson E, Slomka P, Cheng V, Meave A, Saldaña Y, García-Rojas L, Berman D. Fusion of positron emission tomography and coronary computed tomographic angiography identifies fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the left main coronary artery soft plaque. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2008;15:841–843. doi: 10.1007/BF03007367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett HH, Myers KJ. Foundations of Image Science. New York: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Blockmans D, Maes A, Stroobants S, Nuyts J, Bormans G, Knockaert D, Bobbaers H, Mortelmans L. New arguments for a vasculitic nature of polymyalgia rheumatica using positron emission tomography. Rheumatology. 1999;38:444–447. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume M, Martinez-Moller A, Keil A, Navab N, Rafecas M. Joint Reconstruction of Image and Motion in Gated Positron Emission Tomography. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2010;29(11):1892–1906. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2053212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher L, Rodrigue S, Lecomte R, Bénard F. Respiratory gating for 3-dimensional PET of the thorax: feasibility and initial results. J. Nucl. Med. 2004;45:214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AP, Farb A, Malcom GT, Liang YH, Smialek J, Virmani R. Coronary risk factors and plaque morphology in men with coronary disease who died suddenly. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1276–1282. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705013361802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun S, Fessler J. A simple regularizer for B-spline nonrigid image registration that encourages local invertibility. IEEE J. Sel. Topics in Signal Process. 2009;3(1):159–169. doi: 10.1109/JSTSP.2008.2011116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun SY, Reese TG, Ouyang J, Guerin B, Catana C, Zhu X, Alpert NM, El Fakhri G. MRI-Based Nonrigid Motion Correction in Simultaneous PET-MRI. J Nucl. Med. 2012;53:1284–1291. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.092353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen P, et al. Rupture of the Atherosclerotic Plaque: Does a Good Animal Model Exist? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:535–542. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000060200.73623.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defrise M, Kinahan P. Data acquisition and image reconstruction for 3D PET. In: Bendriem B, Townsend DW, editors. The Theory and Practice of 3D PET. Norwell, MA: Kluwer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Delso G, Martinez-Möller A, Bundschuh RA, Nekolla SG, Ziegler SI, Schwaiger M. Preliminary study of the detectability of coronary plaque with PET. Phys. Med. Biol. 2011;56:2145. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/7/016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunphy MP, Freiman A, Larson SM, Strauss HW. Association of vascular 18F-FDG uptake with vascular calcification. J. Nucl. Med. 2005;46:1278–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElFakhri G, Surti S, Trott CM, Scheuermann J, Karp JS. Improvement in Lesion Detection with Whole-Body Oncologic Time-of-Flight PET. J. Nucl. Med. 2011;52(3):347–353. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.080382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farb A, Burke AP, Tang AL, Lian Y, Mannan P, Smialek J, Virmani R. Coronary plaque erosion without rupture into a lipid core. A frequent cause of coronary thrombosis in sudden coronary death. Circulation. 1996;93:1354–1363. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.7.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover GH, Schneider E. Three-point Dixon technique for true water/fat decomposition with B0 inhomogeneity correction. Magn. Reson. Med. 1991;18:371–383. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb JW. Fat-water separated delayed hyperenhanced myocardial infarct imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2008;60:503–509. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin B, Cho S, Chun SY, Zhu X, Alpert NM, El Fakhri G, Reese T, Catana C. Non-rigid PET motion compensation in the lower abdomen using simultaneous tagged-MRI and PET imaging. Med. Phys. 2011;38(6):3025–3038. doi: 10.1118/1.3589136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havla L, Basha T, Rayatzadeh H, Shaw JL, Manning WJ, Reeder SB, Kozerke S, Nezafat R. Improved Fat Water Separation With Water Selective Inversion Pulse for Inversion Recovery Imaging in Cardiac MRI. J. Mag. Res. Imag. 2012;37(2):484–490. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Dutta J, Petibon Y, Reese TG, Li Q, Catana C, El Fakhri G. A novel golden-angle radial FLASH motion-estimation sequence for simultaneous thoracic PET-MR. Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 2013;21:2462. [Google Scholar]

- Jan S, et al. GATE: a simulation toolkit for PET and SPECT. Phys. Med. Biol. 2004;49:4543–4561. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/19/007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Chan C, Mulnix T, Panin V, Casey ME, Liu C, Carson RE. List-mode reconstruction for the Biograph mCT with physics modeling and event-by-event motion correction. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013;58:5567. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/16/5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellman P, Hernando D, Shah S, Zuehlsdorff S, Jerecic R, Mancini C, Liang Z, Arai AE. Multi-echo Dixon Fat and Water Separation Method for Detecting Fibro-fatty Infiltration in the Myocardium. Magn. Reson. Med. 2009;61(1):215–221. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Khurd P, Hsiao I, Zhou L, Gindi G. A channelized Hotelling observer study of lesion detection in SPECT MAP reconstruction using anatomical priors. Phys. Med. Biol. 2007;52:3601–3617. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/12/017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–1143. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magder S. Clinical Usefulness of Respiratory Variations in Arterial Pressure Amer. J Respiratory Critical Care Med. 2004;169:151–155. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1360CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller JE, Abela GS, Nesto RW, Tofler GH. Triggers, acute risk factors and vulnerable plaques: the lexicon of a new frontier. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:809–813. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell WG, Moore CC, Hunter WC, Zerhouni EA, McVeigh ER. Three-dimensional myocardial deformations: calculation with displacement field fitting to tagged MR images. Radiology. 1995;195:829–835. doi: 10.1148/radiology.195.3.7754016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, et al. 18F-FDG accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques: immunohistochemical and PET imaging study. J. Nucl. Med. 2004;45:1245–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellman P, Hernando D, Arai AE. Myocardial Fat Imaging. Curr. Cardiovasc. Imaging Rep. 2010;3:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s12410-010-9012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petibon Y, Ouyang J, Zhu X, Huang C, Reese TG, Chun SY, Li Q, El Fakhri G. Cardiac motion compensation and resolution modeling in simultaneous PET-MR: a cardiac lesion detection study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013;58:2085. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/7/2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder SB, Wen Z, Yu H, Pineda AR, Gold GE, Markl M, Pelc NJ. Multicoil Dixon chemical species separation with an iterative least-squares estimation method. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004;51:35–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers IS, Nasir K, Figueroa AL, Cury RC, Hoffmann U, Vermylen DA, Brady TJ, Tawakol A. Feasibility of FDG imaging of the coronary arteries comparison between acute coronary syndrome and stable angina. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Img. 2010;3:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd JH, et al. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2002;105:2708–2711. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020548.60110.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segars WP, Tsui BMW. MCAT to XCAT: the evolution of 4-d computerized phantoms for imaging research. IEEE Conf. Proc. 2009;97:1954–1968. doi: 10.1109/JPROC.2009.2022417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddon RL. Fast calculation of the exact radiological path for a three dimensional CT array. Med. Phys. 1985;12:252–255. doi: 10.1118/1.595715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvera SS, El Aidi H, Rudd JHF, Mani V, Yang L, Farkouh M, Fuster V, Fayad ZA. Multimodality imaging of atherosclerotic plaque activity and composition using FDG-PET/CT and MRI in carotid and femoral arteries. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207(1):139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slomka PJ, Nishina H, Berman DS, Kang X, Akincioglu C, Friedman JD, Hayes SW, Aladl UE, Germano G. “Motion-frozen” display and quantification of myocardial perfusion. J. Nucl. Med. 2004;45:1128–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawakol A, et al. In vivo 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging provides a noninvasive measure of carotid plaque inflammation in patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;48:1818–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawakol A, Migrino RQ, Hoffmann U, Abbara S, Houser S, Gewirtz H, Muller JE, Brady TJ, Fischman AJ. Noninvasive in vivo measurement of vascular inflammation with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2005;12(3):294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teräs M, Kokki T. Dual-gated cardiac PET – Clinical feasibility study. Eur J Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2010;37:505–516. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykrzykowska J, Lehman S, Williams G, Parker JA, Palmer MR, Varkey S, Kolodny G, Laham R. Imaging of Inflamed and Vulnerable Plaque in Coronary Arteries with 18F-FDG PET/CT in Patients with Suppression of Myocardial Uptake Using a Low-Carbohydrate, High-Fat Preparation. J. Nucl. Med. 2009;50:563–568. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.055616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]