Abstract

We work from a life course perspective to assess the impact of marital status and marital transitions on subsequent changes in the self-assessed physical health of men and women. Our results suggest three central conclusions regarding the association of marital status and marital transitions with self-assessed health. First, marital status differences in health appear to reflect the strains of marital dissolution more than they reflect any benefits of marriage. Second, the strains of marital dissolution undermine the self-assessed health of men but not women. Finally, life course stage is as important as gender in moderating the effects of marital status and marital transitions on health.

Married individuals are, on average, healthier than their unmarried counterparts, and men appear to receive more benefits from marriage than women (Hemstrom 1996; Lillard and Waite 1995; Rogers 1995). Recent research, however, raises serious questions about this general conclusion. An alternative explanation is that marital status differences in health result from the substantial but transient strains of marital dissolution. Despite much speculation about the processes responsible for marital status differences in health, most attempts to answer this question have been constrained by the use of cross-sectional data. We employ nationally representative longitudinal data to examine the impact of transitions into and out of marriage on the self-assessed health status of men and women. Further, we consider whether the effects of marital transitions on men’s and women’s physical health endure or attenuate with time.

We also integrate a life course perspective with research and theory on marriage and health to investigate whether the benefits of being married or the strains of marital dissolution differentially affect the health of young, mid-life, and older men and women. The life course perspective suggests that the timing of role transitions and statuses influences their effects on well-being (Elder 1985; see George 1993). Applying a life course framework to research on marriage and health helps to clarify who is most likely to benefit from marriage and to identify those who are most vulnerable to the negative effects of marital dissolution.

THEORETICAL AND EMPIRICAL BACKGROUND

Marital Status, Marital Transitions, and Health: Resource or Crisis?

Married individuals report better self-assessed health, have lower rates of long-term illness, are less depressed, and live longer than their unmarried counterparts (Hemstrom 1996; Lillard and Waite 1995; Ross, Mirowsky, and Goldsteen 1990). Theoretical explanations for the link of marital status with health typically take one of two forms. The marital resource model suggests that marital status differences in health result from the greater economic resources, social support, and regulation of health behaviors that the married enjoy (Ross et al. 1990; Umberson 1992). In contrast, the crisis model emphasizes that marital status differences in health exist primarily because the strains of marital dissolution undermine health (Booth and Amato 1991; Williams, Takeuchi, and Adair 1992). Two methodological conventions—a heavy reliance on cross-sectional data and a failure to distinguish between marital status at one point in time and marital transitions—make it difficult to sort out the relative contributions of each explanation. For example, the crisis model predicts that after a temporary decline in health following a transition out of marriage, the health of the divorced or widowed should be no different from that of the married.

Although previous research has not examined the relative merits of the crisis and the resource model in accounting for marital status differences in physical health, recent studies of the effects of marital status and marital transitions on mental health offer some insight. This research suggests that the crisis model is more applicable than the marital resource model in accounting for the better mental health of the married compared to the unmarried. For example, Booth and Amato (1991) find that psychological distress increases just prior to divorce, remains elevated for a few years, and eventually returns to levels that are similar to those reported by the continually married. Similarly, longitudinal research on bereavement suggests that there may be few long-term effects of widowhood on mental health (McCrae and Costa 1993).

Cross-sectional research on marital status and psychiatric disorder also provides indirect support for the crisis model. Williams et al. (1992) find that, although the never-married, divorced, and widowed all presumably lack the resources that marriage provides, it is only the previously married who appear to be psychologically disadvantaged by being unmarried. However, research describing the effect of marital status and marital transitions on mental health cannot be automatically generalized to physical health. Despite substantial comorbidity, the etiologies of mental and physical disorders differ considerably (Thoits 1995). In the present study, we consider the relative importance of the crisis model and the marital resource model in explaining marital status differences in physical health. In addition to distinguishing between marital status continuity and marital transitions, we investigate whether the negative health consequences of transitions out of marriage attenuate with time.

Focusing on the physical health consequences of marital transitions also allows for the examination of a neglected issue: the effects of transitions into marriage on health. Little is known about the short-term processes through which entry into marriage and the lifestyle adjustments that it may entail affect health and well-being. If marital status differences in health reflect resources provided by marriage, transitions into marriage should be associated with improved health, and this advantage should persist or increase with time. Yet research on mental health provides little support for this conclusion. Horwitz and White (1991) find no evidence that the transition into first marriage reduces depression among young adults. Although other studies suggest that transitions into marriage are associated with a decline in depression (Simon and Marcussen 1999), it is unclear whether these results are permanent or temporary. As Marks and Lambert (1998) point out, failure to consider these temporal changes may overstate the greater well-being of the married compared to the never-married.

In sum, although marriage may benefit individuals in ways that ultimately enhance health, recent research on mental health suggests that the average effects of marital status and marital transitions on physical health will provide greater support for the crisis model than the marital resource model. Thus, we expect that transitions out of marriage will be associated with declines in health while continuity in an unmarried status will not undermine health. Moreover, we expect that declines in health will be sharpest immediately following a transition to divorce or widowhood and will dissipate with time. Although less is known about the health consequences of entering marriage, research on psychological well-being suggests that transitions into first marriage should be associated with improved health immediately following the transition, but these effects may attenuate over time.

The Life Course Perspective

The life course perspective emphasizes that the timing of role transitions creates an important social context that influences: (1) the ease with which new roles are incorporated into one’s identity, (2) the normative status and social acceptance of new roles, (3) the resources that are available to adjust to the new role and, consequently, (4) the effect of these roles and transitions on well-being (Elder 1985). Age and other life course markers are associated with a range of psychosocial and structural attributes—all of which may impinge on the process through which marriage and marital transitions affect health.

The stress process is central to the crisis explanation of marital status differences in health and well-being. Viewing the stress paradigm through a life course lens suggests two key reasons to suspect that the effects of marital transitions on health and well-being may vary by age. First, exposure to multiple stressors increases vulnerability to additional stressful life events or chronic strains (Ulbrich, Warheit and Zimmerman 1989). Because many older adults experience a pile-up of stressors associated with the death of significant others and declines in economic well-being (Mirowsky and Ross 1992; Ensel et al. 1996), the negative effects of marital dissolution on self-assessed health should be greater for older compared to younger individuals. In support of this hypothesis, recent research on life course variations in the stress process indicates that “the significance of stressors in explaining why we are depressed increases as we proceed through the life course (Ensel et al. 1996:412).” Similarly, cross-sectional research suggests that undesirable events such as deaths of significant others are more strongly associated with the physical health symptoms of older compared to younger adults (Ensel and Lin 2000).

Second, a key premise of stress research is that the extent to which exposure to a role-related stressor (i.e., marriage, parenthood) undermines health and well-being depends on the salience of that role to the individual (Simon 1997). According to socioemotional selectivity theory, in later years, individuals begin to restrict their social networks to focus more exclusively on their primary relationships, including marriage (Carstensen 1992). If the marital relationship becomes more salient to individuals at later ages, exits from marriage should more strongly undermine the health of older compared to younger adults.

Life course differences in the effects of transitions into marriage are more difficult to predict. Life course theory suggests that occupying particular roles at non-normative stages of the life course may undermine well-being (Elder 1985). Clearly, being never-married is common among younger adults, especially given recent increases in the age at first marriage. Older individuals may have more to gain by becoming married because this transition involves an exit from a non-normative status.

Gender, Marriage, and Health across the Life Course

A traditional and central focus of research on marriage and health is gender difference, and the physical health advantage of marriage appears to be greater for men than for women (Hemstrom 1996; Lillard and Waite 1995; Rogers 1995). According to the marital resource model, marriage provides more benefits to men in the form of a healthy lifestyle, emotional support, and physical comfort. However, the conclusion that marriage is more strongly associated with men’s health than women’s is based primarily on research that examines the effect of marital status at one point in time on present or later health. Thus, we do not know if transitions into or out of marriage have different consequences for the health of women and men.

There are a number of reasons to expect that they may. Despite a convergence of gender roles, women continue to assume more parental and household responsibilities than men (Lennon and Rosenfield 1994). Thus, it is likely that exiting and entering marriage entails a different balance of rewards and costs for women and men. Certainly, previous research suggests that men’s health benefits more than women’s from being married (Lillard and Waite 1995). As Phyllis Moen’s research indicates, “the intersection of age and gender produces distinctive life patterns for men and women at all stages of the life course” (Moen 1996:171). These life patterns form the context in which marriage and marital transitions are experienced and, therefore, have important implications for the association of marital status with health. Our analysis considers the possibility that life course stage moderates the association between marital status/transitions and health in different ways for men and women.

Hypotheses

In sum, recent research on marriage and mental health, the stress process, and the life course perspective lead us to argue that commonly observed gender and marital status differences in health are better explained with a crisis model than a marital resource model. We contend that a carefully nuanced analysis of marital status and health that takes into account the time spent in the status, marital transitions, and life course position will support the crisis model and shed light on gender differences in the costs and benefits of marriage for health. We test seven basic hypotheses:

| H1 | self-assessed health of continually married men and women does not differ from that of their continually divorced, widowed, or never-married counterparts. |

| H2 | Transitions out of marriage through divorce or widowhood are associated with an initial decline in self-assessed health, but this decline dissipates with time. |

| H3 | Initial declines in self-assessed health associated with exiting marriage are greater for older compared to younger adults |

| H4 | Initial declines in self-assessed health associated with exiting marriage are greater for men compared to women. |

| H5 | Transitions into marriage are associated with initial improvement in self-assessed health, but this benefit attenuates with time. |

| H6 | The initial improvement in self-assessed health associated with entering marriage is greater for older compared to younger adults. |

| H7 | The initial improvement in health self-assessed health associated with entering marriage is greater for men compared to women. |

DATA AND MEASURES

Data

Data are from the first, second, and third waves (1986, 1989, and 1994) of the Americans’ Changing Lives survey (House 1986). Interviews were conducted with a nationally representative sample of 3,617 persons ages 24 and older in 1986 residing in the contiguous United States. Of the 3,617 respondents interviewed in 1986, 65 percent (n = 2,348) were also interviewed in 1989 and 1994. The attrition rate for all waves of data collection is 35 percent (n = 1,269). Mortality of respondents was responsible for 43 percent of the attrition (n = 546) and nonresponse was responsible for 57 percent (n = 723). The sample was obtained using multistage area probability sampling with an oversample of African Americans and older individuals. All analyses presented here are weighted to adjust for the oversample of special populations and the attrition that occurred between waves.

Analytic Approach

Analyses reported here are based on a standard cross-sectional time-series, or panel, design. To take full advantage of the available data, we pool the three waves of. This provides two survey waves with information on the respondent at the current survey wave and the previous wave. Since there are two observations for the 2,348 respondents who participated in all three waves of data collection, standard errors are adjusted for the clustering of observations within individuals.1 We also control for months elapsed between Time 1 and Time 2. Estimates of the association of marital transitions with changes in health are obtained using regression with lagged dependent variables.2

There are two advantages to pooling data. First, this approach increases the age range of respondents who experience marital status transitions of interest and therefore widens the age range across which our results can be generalized. Second, this analytic strategy increases the cell size of respondents experiencing specific marital status transitions, and it reduces the probability that a lack of statistical power will result in a failure to observe a significant effect of marital status or a significant age difference in the association of marital status with health in those instances when these effectsexist (i.e., a Type II error).

Measures

Marital status continuity and change

Dummy variables represent continuity and change between Time 1 and Time 2 in the following marital statuses: (1) continually married, (2) continually never married, (3) continually divorced, (4) continually widowed, (5) married to divorced, (6) married to widowed, (7) never married to married, and (8) divorced or widowed to remarried. Respondents experiencing more than one marital transition between waves and those whose marital history could not be classified due to missing or inconsistent data are excluded. Because the consequences of divorce and separation for health may differ, respondents who transitioned from married to separated and those who were continually separated between Time 1 and Time 2 are also excluded.

Self-assessed health

Self-assessed health is measured with responses to the following question: “How would you rate your health at the present time?” Response categories range from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). Self-assessed health is widely recognized as a valid indicator of overall health status (Ferraro and Farmer 1999).

Life course stage and marital status duration

Life course stage is measured with a continuous variable that indicates the age of the respondent in years at Time 1. To facilitate interpretation, the age variable is centered at 24 years, the youngest age of respondents in the 1986 panel. Analyses (not shown) indicated that neither an age-squared lower-order coefficient nor any of the interactions with age-squared were significant. We also consider the effects of the duration in months of the marital status occupied at Time 2. Internal moderators test whether the effects of marital transitions on health depend upon the number of months spent in the new status at Time 2. The internal moderator terms are constructed by centering the Time 2 marital status duration variable at the mean and assigning a value of zero to those in the reference category.

Sociodemographic control variables

All models include controls for the Time 1 values of the following sociodemographic variables: race (African American = 1; all others = 0); education, in years; annual household income (a range of 1 to 10); and employment status (1 = employed; 0 = unemployed). We also control for the number of months elapsed between Time 1 and Time 2. Weighted means and standard deviations of all variables of the analysis are presented separately for women and men in Table 1. Table 1 also shows the mean, standard deviation, and range for age of respondents in each marital status category.

TABLE 1.

Weighted Means and Standard Deviations for All Variables in the Analysis: U.S. Women and Men Ages 24–96 in 1986

| Total Sample |

Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (s.d.) |

Mean (s.d.) |

Mean Age (s.d.) |

Age Range |

Mean (s.d.) |

Mean Age (s.d.) |

Age Range |

|

| Continually married | .668 (.471) |

.605 (.489) |

46.196 (14.067) |

25–87 | .729 (.439) |

46.735 (14.125) |

25–89 |

| Continually never-married | .082 (.274) |

.068 (.251) |

39.792 (14.746) |

24–88 | .097 (.297) |

39.399 (13.512) |

25–82 |

| Continually divorced | .081 (.273) |

.093 (.291) |

46.559 (13.338) |

25–84 | .067 (.251) |

46.078 (13.304) |

28–85 |

| Continually widowed | .088 (.284) |

.141 (.348) |

69.115 (11.404) |

28–98 | .028 (.166) |

66.095 (15.986) |

26–90 |

| Married to divorced | .021 (.143) |

.021 (.142) |

37.023 (8.197) |

25–68 | .022 (.146) |

40.652 (10.864) |

25–82 |

| Married to widowed | .020 (.141) |

.032 (.177) |

66.327 (11.260) |

27–89 | .020 (.083) |

73.975 (9.079) |

43–85 |

| Never-married to married | .017 (.130) |

.013 (.115) |

32.360 (6.567) |

25–67 | .022 (.146) |

32.458 (10.032) |

25–76 |

| Divorced or widowed to remarried | .023 (.151) |

.028 (.165) |

39.019 (11.042) |

25–81 | .028 (.166) |

42.085 (10.130) |

25–76 |

| Self-assessed health T1 | 3.663 (1.007) |

3.595 (1.021) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

3.741 (.986) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Self-assessed health T2 | 3.530 (1.032) |

3.465 (1.038) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

3.604 (1.020) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Age T1a | 47.745 (15.655) |

49.121 (16.294) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

46.185 (14.747) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Months between T1 and T2 | 44.386 (14.296) |

44.312 (14.262) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

44.470 (14.339) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| African American | .096 (.294) |

.102 (.303) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

.088 (.284) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Education in years T1 | 12.625 (2.967) |

12.356 (2.870) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

12.931 (3.045) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Employed T1 | .646 (.478) |

.533 (.499) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

.773 (.419) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Income T1 (1–10) | 5.769 (2.597) |

5.346 (2.691) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

6.249 (2.398) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Unweighted n (observations) | 4,773 | 3,050 | --- | --- | 1,723 | --- | --- |

| Weighted n (observation) | 4.773 | 2,544 | --- | --- | 2,228 | --- | --- |

Zero-order correlations of sociodemographic variables and health (not shown) indicate that the data reproduce established positive associations of education, income, and being employed with self-assessed health. Similarly, age, being female, and being African American are negatively correlated with health. We estimated preliminary cross-sectional models for the association of Time 1 marital status with Time 1 health. The results (not shown) are largely consistent with prior research and suggest that, controlling for age, widowed men and divorced men and women have poorer self-assessed health than their married counterparts. The health of the never-married and of widowed women is no worse than that of their married counterparts.3

RESULTS

Continuity in an Unmarried Status

We first test the hypothesis that the health of the continually unmarried does not differ from that of their married counterparts. Estimates are obtained using ordered probit models, which make full use of the five-point scale on which respondents assess their health. Because some respondents who are continually married or unmarried for less than five years will be included in marital transition groups in later analyses, they are excluded from the present models. We control for Time 1 values of sociodemographic variables that may influence marital status and health. Income, however, is excluded because it has been identified as a potential mechanism through which marital status influences health and well-being (Ross et al. 1990). Results of the base model are presented in model 1 of Table 2, and the final interaction model is presented in model 2.

TABLE 2.

Ordered Probit Regression Coefficients and Robust Standard Errors from Models Estimating the Effects of Continuity in an Unmarried Status T1-T2 on T2 Self-Assessed Health (n=4,342 observations)

| Independent variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Continually unmarried (0 = Continually married) | ||

| Continually never-married | .040 (.086) |

.077 (.188) |

| Continually never-married X age | --- --- |

.003 (.008) |

| Continually never-married X female | --- --- |

−.000 (.266) |

| Continually never-married X age X female | --- --- |

−.012 (.010) |

| Continually divorced | −.075 (.079) |

.036 (.278) |

| Continually divorced X age | --- --- |

−.007 (.009) |

| Continually divorced X female | --- --- |

−.235 (.318) |

| Continually divorced X age X female | --- --- |

.013 (.011) |

| Continually widowed | −.002 (.074) |

−1.577*** (.382) |

| Continually widowed X age | --- --- |

.036*** (.010) |

| Continually widowed X female | --- --- |

1.335*** (.484) |

| Continually widowed X age X female | --- --- |

−.029* (.012) |

| Age T1 a | −.007** (.002) |

−.005 (.003) |

| Female | .007 (.053) |

.109 (.121) |

| Female X age | --- --- |

−.004 (.004) |

| Months between T1 and T2 interviews | .000 (.001) |

.000 (.001) |

| African American (0 = White) | −.217*** (.058) |

−.216*** (.058) |

| Education in years | .059*** (.009) |

.060*** (.009) |

| Employed (0 = unemployed) | .350*** (.069) |

.361*** (.069) |

| cut 1 | −1.068 | −1.024 |

| cut 2 | −.236 | −.191 |

| cut 3 | .663 | .709 |

| cut 4 | 1.851 | 1.902 |

p≤.05

p≤.01

p≤.001 (two-tailed tests)

Age is centered at 24 years.

Basic associations

The ordered probit model (model 1) compares the average probability of reporting the next highest level of self-assessed health at Time 2 among the continually married (reference category) to that of the continually never-married, divorced, and widowed. In support of Hypothesis 1, marital status differences in Time 2 self-assessed health are small and do not reach statistical significance.

Life course and gender

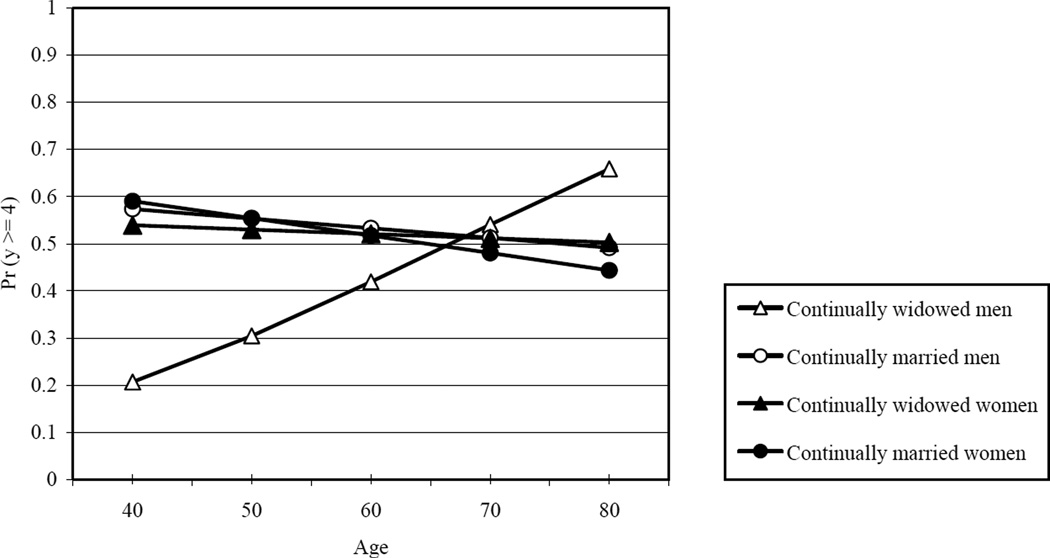

Model 2 of Table 2 indicates that the estimated effect of continuity in the widowed status on Time 2 health is moderated by gender and age. Because ordered probit models do not measure the dependent variable on an inherently meaningful scale, coefficients can be more easily interpreted by calculating the predicted probability of reporting a particular value or values of self-assessed health as a function of the independent variables in the analysis (see Stolzenberg 2001). Further, to describe the nature of a significant interaction, it is necessary to plot these predicted probabilities at different values of the variables that comprise the interaction term. We calculate, at 10-year age intervals, the predicted probabilities of reporting “excellent” or “very good” health for continually married and continually widowed men and women.4

The associations represented by the three-way interaction between gender, age, and continuity in the widowed status are shown in Figure 1. Contrary to our hypothesis that the health of the continually unmarried would not differ from that of the married, Figure 1 indicates that continuity in the widowed status is significantly associated with men’s self-assessed health. The direction of this association, however, is highly dependent on age. At age 40, continually widowed men have a substantially lower probability of being in excellent or very good health at Time 2 (20.6 percent) than their continually married counterparts (57.1 percent).5 This difference diminishes with age and reverses direction at approximately age 68 ([1.577 / .036] + 24).6 At approximately 60 years of age and older, differences in the health of continually widowed and continually married men are not statistically significant. Among women, the health of the continuously widowed does not differ significantly from that of the continually married.

FIGURE 1.

Estimated Probability of Excellent or Very Good Self-Assessed Health at Time 2 among the Continually Widowed and Continually Married, by Age and Gender

Note: Model controls for the Time 1 values of health, age, income, education, race, and employment status, and for the number of months elapsed between Time 1 and Time 2.

Transitions out of Marriage

We use ordered probit models with lagged dependent variables to test the second hypothesis that transitions out of marriage undermine health. We also consider whether these effects are: (1) greater for men than for women, (2) increase with age, and (3) diminish with time since the transition. The sign of coefficients in lagged dependent variable models reflect the direction of change in the dependent variable across the period of time under consideration (Kessler and Greenberg 1981). Thus, in the present models, a positive coefficient indicates that a transition out of marriage is associated with an increase in the probability of reporting the next highest level of self-assessed health between Time 1 and Time 2, and a negative coefficient reflects a decrease in the probability of reporting the next highest level of self-assessed health, relative to the change that is experienced by the continually married. Interpreting the size of the coefficient in ordered probit models requires some calculation, and we describe this in more detail below. Control variables include those described in previous models in addition to: (1) Time 1 self-assessed health and (2) Time 1 income.7

Basic associations

The estimated main effects of transitions out of marriage on self-assessed health are presented in model 1 of Table 3. Model 1 shows that the transition to divorce, but not the transition to widowhood, is associated with an increase in the probability of reporting the next highest level of self-assessed health. The ordered probit coefficient for the transition to divorce can be interpreted in the following manner: If a continually married person has a 50 percent chance of being in excellent or very good health at T2, controlling for Time 1 health, then that probability is about 17 percentage points higher, or 67 percent among those who experience the transition to divorce.8 These findings can be interpreted as indicating that the transition to divorce is associated with a 17 percentage-point increase between Time 1 and Time 2 in the probability of being in excellent or very good health. The transition to widowhood is not significantly associated with change in health in model 1. Although these findings fail to support Hypothesis 2, subsequent analyses indicate that the magnitude and direction of these associations are highly dependent on gender, life course stage, and time since exiting marriage.

TABLE 3.

Ordered Probit Regression Coefficients and Robust Standard Errors from Models Estimating the Effects of Transitions out of Marriage on Change in Self-Assessed Health Time1 – Time 2 (n=2,808 observations)

| Independent variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Transitions out of marriage (0 = continually married) | ||

| Married to divorced | .434** (.148) |

1.542*** (.434) |

| Married to divorced X duration a | −.019 (.013) |

|

| Married to divorced X age | --- --- |

−.052** (.020) |

| Married to divorced X female | --- --- |

−1.456** (.545) |

| Married to divorced X duration X female | .009 (.016) |

|

| Married to divorced X age X female | --- --- |

.067** (.027) |

| Married to widowed | −.078 (.105) |

2.588* (1.166) |

| Married to widowed X duration | .036* (.015) |

|

| Married to widowed X age | --- --- |

−.061* (.024) |

| Married to widowed X female | --- --- |

−2.993* (1.216) |

| Married to widowed X duration X female | --- --- |

−.037* (.016) |

| Married to widowed X age X female | .071** (.025) |

|

| T1 Self-Assessed Health | .763*** (.034) |

.766*** (.034) |

| Age T1b | −.006*** (.002) |

−.003 (.003) |

| Female | .001 (.051) |

.101 (.104) |

| Female X age | --- --- |

−.004 (.003) |

| Months between T1 and T2 interviews | .005** (.002) |

.005** (.002) |

| African American (0 = White) | −.093 (.061) |

−.097 (.062) |

| Household income (1 – 10) | .014 (.012) |

.014 (.012) |

| Education in years | .020* (.011) |

.020* (.010) |

| Employed (0 = unemployed) | .047 (.074) |

.055 (.075) |

| cut 1 | .855 | .922 |

| cut 2 | 1.923 | 1.991 |

| cut 3 | 3.072 | 3.145 |

| cut 4 | 4.521 | 4.601 |

p≤.05

p≤.01

p≤.001 (one-tailed tests)

Duration is centered at the mean of 24 months for this subsample.

Age is centered at 24 years.

Life course, gender, and duration

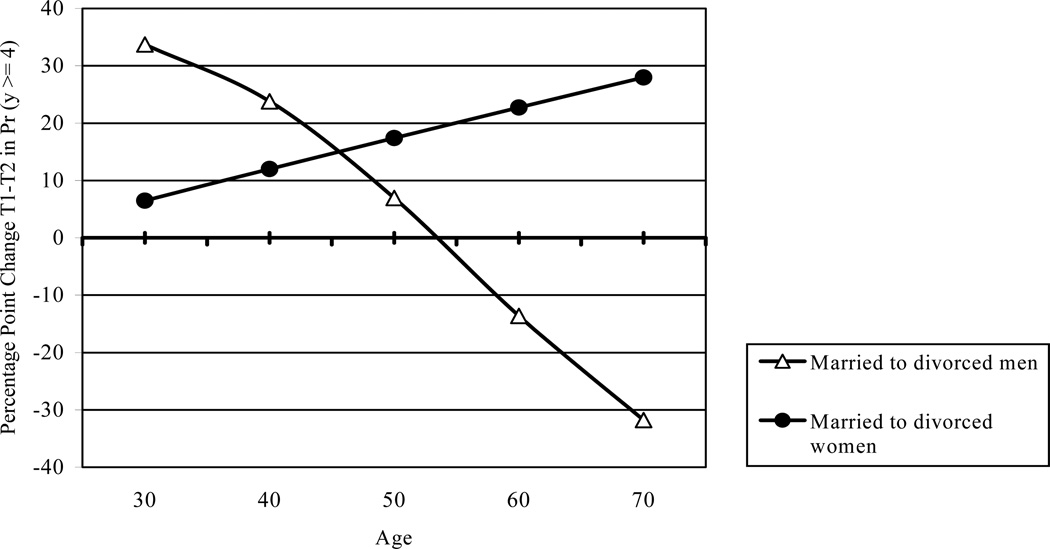

Several interaction terms are significant in model 2 of Table 3. Figure 2 shows, at ten-year age intervals, the predicted percentage point change in the probability of reporting excellent or very good health that is associated with the transition to divorce for men and women.9 The most striking pattern is the following: For 30-year-old men, the transition to divorce is associated with a 34 percentage point increase in the probability of being in excellent or very good health. However, this advantage diminishes with age and reverses direction (from an increase to a decrease in health) at approximately age 54 ([−1.542 / −.052] + 24).10 Among the oldest men who experience the transition to divorce (e.g., age 70), the transition to divorce is associated with a 32 percentage point decrease in the probability of reporting excellent or very good health. In sum, the negative effects of the transition to divorce are greater for older compared to younger men, an observation that supports Hypothesis 3. In addition, divorce appears to be advantageous to the health of younger men.

FIGURE 2.

Estimated Percentage Point Change in the Probability of Excellent or Very Good Health (Time 1-Time 2) Associated with the Transition to Divorce by Age and Gender

Note: Model controls for the Time 1 values of health, age, income, education, race, and employment status, and for the number of months elapsed between Time 1 and Time 2.

The transition to divorce does not significantly undermine women’s health at any age that we consider. In fact, the benefits of divorcing among women increase with age so that for 70-year-old women the transition to divorce is associated with a 28 percentage point increase in the probability of reporting excellent or very good health. We find no evidence that the effects of the transition to divorce on change in self-assessed health attenuate across the 3-year to 5-year period examined here. Although preliminary analysis indicated that time since divorce does not interact with both gender and age to moderate the association of the transition to divorce with health (i.e., a four-way interaction), we cannot rule out the possibility of a Type II error because of the small number of men and women experiencing the transition to divorce at each combination of age and duration values. In sum, we find support for Hypothesis 4 among older adults.

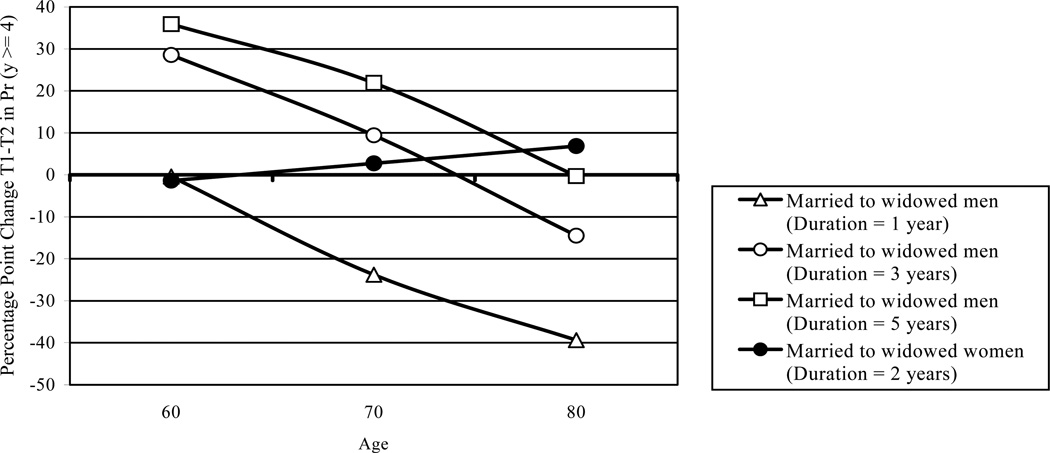

We next examine the complex associations of gender, age, duration, and the transition to widowhood with self-assessed health. Both of the three-way interactions of these variables are statistically significant. The nature of these interactions is described in Figure 3. As shown, the transition to widowhood does not significantly undermine women’s self-assessed health at any age that we consider. In contrast, the estimated effect of the transition to widowhood on men’s health varies with age and time since the spouse’s death. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, it is only recently widowed men (plotted at 1 year) who show a significant decline in the probability of reporting excellent or very good health. Depending on their ages, some men who have been widowed three years by T2 show increases in the probability of being in excellent or very good health. This pattern likely reflects recovery from the negative health consequences of having a sick spouse at Time 1, as well as recovery from the decline in health that may occur in the first year after a wife’s death.

FIGURE 3.

Estimated Percentage Point Change in the Probability of Excellent or Very Good Health (Time 1-Time 2) Associated with the Transition to Widowhood by Age, Duration, and Gender

Note: Model controls for the Time 1 values of health, age, income, education, race, and employment status, and for the number of months elapsed between Time 1 and Time 2. Because duration does not significantly moderate the association of marital status with health among women, the regression line is plotted at the mean duration of 24 months for women.

The results shown in Figure 3 also support Hypothesis 3—that the negative effects of exits from marriage on men’s health become stronger with age. For 70-year-old men, the death of a wife in the past year is associated with a 23.79 percentage point decrease in the probability of being in excellent or very good health, and the death of a wife is associated with a 39.36 percentage point decrease for 80-year-old men. Also consistent with Hypothesis 3 is the observation that any positive associations between the transition to widowhood and men’s health diminish with age. For example, although 60-year-old men widowed three years at Time 2 show an increase in the probability of being in excellent or very good health, the benefits for 70-year-old men are substantially smaller and do not reach statistical significance.

Transitions into Marriage

In the final stage of the analysis, we estimate ordered probit models with lagged dependent variables to test the hypothesis that transitions into marriage improve self-assessed health and that these improvements: (1) are greater for men than for women, (2) are greater for older compared to younger adults, and (3) are greatest immediately following the transition and diminish with time. We estimate separate models to distinguish between transitions into first marriage (reference group = continually never-married) and transitions into remarriage (reference group = continually divorced or widowed for at least 5 years by Time 2).

Basic associations

Table 4 shows that, on average, the transition into first marriage is associated with an increase in self-assessed health across the period considered here. The results in model 1 of Table 4 indicate that, controlling for Time 1 health, if a continually never-married respondent has a 50 percent chance of reporting excellent or very good health at Time 2, then the probability for those who experience the transition into the first marriage is about 19.85 percentage points higher, or 69.85 percent (Ф [Ф−1 (.5) + (1 – 0) (.518)]). In other words, the transition into first marriage is associated with a 19.85 percentage point increase between Time 1 and Time 2 in the probability of reporting excellent or very good health. This is consistent with Hypothesis 5. Remarriage, however, does not offer the same benefits, at least for the average man and woman.

TABLE 4.

Ordered Probit Regression Coefficients and Robust Standard Errors from Models Estimating the Effects of Transitions into Marriage on Change in Self-Assessed Health Time 1 – Time 2

| Independent variable | Transition to 1st Marriage |

Transition to Remarriage |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|

Transition into first marriage (0 = continually never-married) |

||||

| Never-married to married | .518* (.229) |

.773** (.273) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Never-married to married X female | --- --- |

−.650* (.330) |

--- --- |

--- --- |

|

Transition into remarriage (0 = continually divorced or widowed) |

||||

| Divorced / widowed to remarried | --- --- |

--- --- |

.101 (.124) |

.875*** (.252) |

| Divorced / widowed to remarried X female | --- --- |

--- --- |

--- --- |

−.460* (.226) |

| Divorced / widowed to remarried X age | --- --- |

--- --- |

--- --- |

−.027*** (.008) |

| Control variables (for all models) | ||||

| T1 Self-Assessed Health | .519*** (.104) |

.519*** (.103) |

.656*** (.047) |

.655*** (.047) |

| Age T1 a | −.001 (.005) |

−.001 (.005) |

.000 (.003) |

.002 (.003) |

| Female | −.192 (.135) |

−.146 (.139) |

.003 (.100) |

.055 (.108) |

| Female X age | --- --- |

--- --- |

--- --- |

--- --- |

| Months between T1 and T2 interviews | −.013** (.005) |

−.013** (.005) |

.003 (.003) |

.003 (.003) |

| African American (0 = White) | −.026 (.138) |

−.030 (.140) |

−.148* (.077) |

−.146* (.078) |

| Household income T1 (1 – 10) | .068* (.030) |

.067* (.030) |

.019 (.021) |

.018 (.021) |

| Education in years | .006 (.026) |

.009 (.027) |

.043** (.014) |

.042** (.014) |

| Employed (0 = unemployed) | .251 (.180) |

.278 (.178) |

.175 (.103) |

.199 (.103) |

| cut 1 | −.661 | −.612 | 1.112 | 1.209 |

| cut 2 | .681 | .739 | 2.057 | 2.158 |

| cut 3 | 1.626 | 1.687 | 3.123 | 3.235 |

| cut 4 | 2.861 | 2.924 | 4.493 | 4.617 |

| n (observations) | 455 | 455 | 1,369 | 1,369 |

p≤.05

p≤.01

p≤.001 (one-tailed tests)

Age is centered at 24 years.

Life course, gender, and duration

In model 2 of Table 4, we consider whether the effects of transitions into marriage on change in self-assessed health are moderated by age, gender, or time since entering marriage. Preliminary models (not shown) suggested that all of these variables may interact in complex ways (i.e., a four-way interaction) to affect health. However, because only small numbers of men and women experienced each transition into marriage at each combination of age and duration values, we are unable to obtain reliable estimates of four-way interactions. The models presented here include only those two-way and three-way interactions that were significant in preliminary models.

Turning first to the transition into first marriage, the significant interaction with gender in Model 2 of Table 4 suggests that the transition into first marriage is accompanied by a substantial improvement in men’s self-assessed health, but not women’s. Specifically, among men, the transition into first marriage is associated with a 27.94 percentage point increase in the probability of being in excellent or very good health (Ф [Ф−1 (.5) + (1 – 0)(.773)]). The corresponding percentage point increase for women is 4.78 and is not statistically significant (Ф [Ф−1 (.5) + (1 – 0)(.773-.650)]). These findings support the hypothesis that transitions into marriage have more positive effects on men’s health than women’s (Hypothesis 7). However, we find no evidence that the positive consequences of the transition into first marriage for men’s health attenuate over a three- to five-year period.

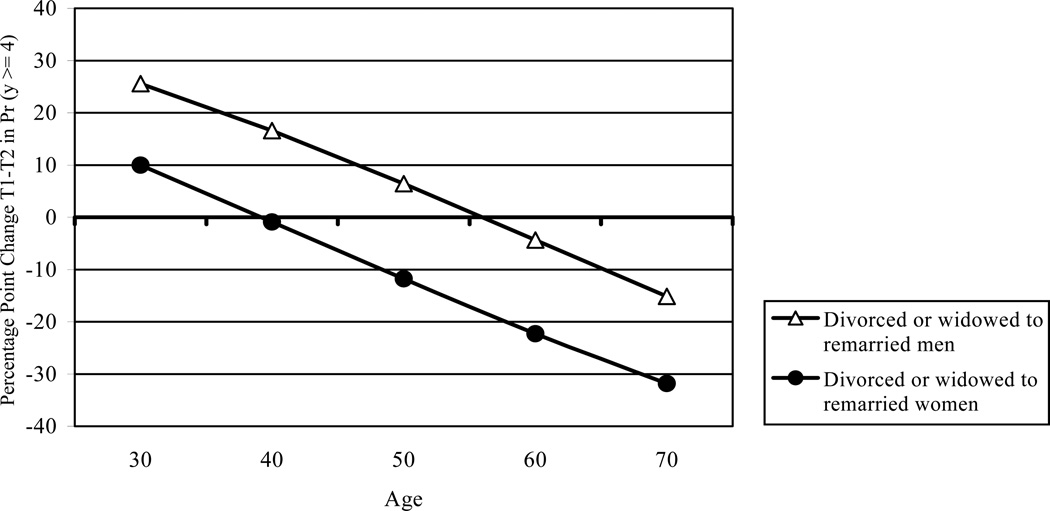

Similarly, the results in model 2 suggest that the effect of the transition into remarriage on change in health depends on both gender and age. The size of the coefficients for the transition to remarriage (.875) and the interaction of the transition to remarriage with gender (-.460) indicate that, among 24-year-olds (centered age), entering a second or later marriage is associated with a substantial improvement in men’s self-assessed health and a much smaller improvement in women’s. This further supports our hypothesis that men receive greater benefits from entering marriage than women.

Moreover, for both men and women, the estimated effect of the transition into remarriage on change in self-assessed health varies with age. The nature of this interaction is depicted graphically in Figure 4. Contrary to our hypothesis that entering marriage would provide greater short-term benefits to the health of older compared to younger adults (H6), the transition to remarriage is associated with an increase in the probability of reporting excellent or very good health only among younger men and women. Further, remarriage appears to undermine the health of the oldest men and women. On average, for 70-year-old men the transition to remarriage is associated with a 15.16 percentage point decrease in the probability of being in excellent or very good health, and this decrease is even greater for 70-year-old women: 31.83 percentage points. We find no evidence that either the positive or the negative effects of the transition to remarriage on health diminish over the 3-year or 5-year year period considered in this model.

FIGURE 4.

Estimated Percentage Point Change in the Probability of Excellent or Very Good Health (Time 1-Time 2) Associated with the Transition to Remarriage, by Age and Gender

Note: Model controls for the Time 1 values of health, age, income, education, race, and employment status, and for the number of months elapsed between Time 1 and Time 2.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest three central conclusions regarding the association of marital status and marital transitions with self-assessed health. Each is consistent with hypotheses suggested by the life course perspective and the social stress model. First, marital status differences in health appear to reflect the strains of marital dissolution more than they reflect the benefits of marriage. Second, the strains of marital dissolution undermine the self-assessed health of men but not women. Finally, in describing the effects of marital status and marital transitions on health, life course stage matters as much as gender.

Theory on Marriage and Health: Resource or Crisis?

Researchers have recently begun to speculate that marital status differences in health primarily reflect the short-term stressors of divorce and widowhood rather than the resources provided by marriage. Our results generally support this argument. If the resources provided by marriage are responsible for marital status differences in health, such differences would be evident among every category of unmarried men and women. They are not: The health of the continually divorced and the never-married is similar to that of the married. Additional support for the crisis model is provided by the observation that, among men, the negative effects of the transition to widowhood are most pronounced immediately following spousal loss and appear to dissipate with time. In fact, men who have been widowed at least three years actually report improved health relative to their married counterparts. This pattern suggests some recovery from the strain of widowhood. That continually widowed men report worse health than the married, however, indicates that complete recovery may be slow or may not occur at all for this group.

Despite generally supporting the crisis model, our results suggest an important modification: Transitions out of marriage do not always undermine health and may in some cases improve it. Our observation that the transition to divorce or widowhood is associated with improved health of young and mid-life men is consistent with research and theory on the stress process. Wheaton suggests that life transitions that might otherwise be stressful may be “nonproblematic, or even beneficial to mental health, when preceded by chronic role problems—a case where more ‘stress’ is actually relief from existing stress” (Wheaton 1990:209). Our results support this argument and provide empirical evidence that stressful events and transitions may also improve physical health when they bring an end to other chronic strains. For young and mid-life men, the transition to divorce may result in recovery from the negative health consequences of being in a strained marriage. Improved health among men widowed between three and five years may reflect a similar process—recovery from initial negative health consequences of widowhood or from strains associated with providing care to a dying spouse.

Our findings should not be interpreted as evidence that marriage provides no measurable health benefits. Rather, it appears that such benefits are not the predominant explanation for previously observed marital status differences in health. In fact, the transition into first marriage and the transition into remarriage are associated with improved health among men. Although preliminary analyses offered no evidence that the advantages of entering marriage diminish within a three-year or five-year period, continually married men are no healthier than their never-married or continually divorced counterparts. This pattern suggests a honeymoon effect in which men’s self-assessed health initially improves upon entering marriage, but then levels off at some point after the three-year to five-year period we examine and becomes similar to that of the unmarried.

Our findings underscore the importance of considering time elapsed since a marital transition when examining health consequences of marriage. We attempt to construct a picture of these time-dependent changes by distinguishing transitions out of marriage from continuity in an unmarried status, and by considering whether duration in a new status moderates the association between marital transitions and health. Our data, however, do not allow us to capture rapid changes in self-assessed health that may occur in the months immediately preceding and following a marital transition. Moreover, due to small cell sizes, we were unable to test whether marital duration interacts simultaneously with both gender and age to moderate the impact of marital transitions on health. Future research employing panel data collected at more frequent intervals with a larger sample should attempt to replicate and elaborate on the present findings.

Our longitudinal analysis represents an improvement over cross-sectional models which raise questions about selection and reverse causal order. The panel data we employ allow us to temporally order our analysis to reduce the probability that associations between marital status with health reflect the influence of health on the probability of becoming and remaining married. We caution, however, that because we do not have information on the precise timing of health changes, we cannot rule out the possibility that changes in health occur before the marital transition of interest. The collection and analysis of data that includes information on the timing of marital transitions as well as the timing of health changes or illness diagnoses could more firmly establish the causal order of the associations we observe.

Refining the Model: Life Course and Gender Variations

Sociologists have long recognized that the effects of marital status on health differ for men and women. Although our results support this conclusion, they indicate that age is an equally important modifier of this association. The health consequences of exiting marriage through divorce or widowhood, of entering a second or later marriage, and of being continually widowed for more than five years are dependent on the age at which these marital transitions and statuses are experienced. Our results consistently indicate that, among men, negative physical health consequences of exiting marriage through divorce or widowhood increase with age.

Age-graded effects of transitions out of marriage on men’s health may partly reflect cohort differences in the functions and experience of marriage. Because men’s relative contribution to household labor has increased in the past three decades (Bianchi et al. 2000), younger cohorts of men are more likely than their older counterparts to have proficiency and experience in tasks associated with maintaining a household. Research on widowhood indicates that the secondary stressors associated with learning and performing these tasks—strains that are more likely to be experienced by older cohorts of men—are partly responsible for the negative effects of widowhood on men’s mental health (Umberson, Wortman, and Kessler 1992).

Research and theory on aging and stress, however, supports the conclusion that vulnerability to the short-term strains of exiting marriage increases across the life course. Socioemotional selectivity theory suggests that marriage becomes more important to older adults as they begin to narrow their social networks (Carstensen 1992). That transitions out of marriage are associated with the greatest declines in the health of older men supports this conclusion. It is also likely that younger adults find it easier to resume life as a single person, including greater ease in dating. Prior research also indicates that vulnerability to stressful life events increases with age (Ensel and Lin 2000), a conclusion that is consistent with the present results.

A notable exception to the conclusion that marriage becomes more important to health at later ages is the observation that continuity in the widowed status is worse for younger compared to older men. We suspect that this pattern partly reflects the unique stressors associated with experiencing an unexpected loss. The life course perspective predicts that roles and transitions experienced at non-normative stages of the life course may undermine well-being (Elder 1985). The death of a spouse at a young age involves substantial restructuring of life plans and may result in single-parenthood, a role that may be particularly stressful for men who typically do not assume primary responsibility for the care of children.

We also find support for the hypothesis that transitions out of marriage more negatively affect men’s health than women’s, at least among older adults. Indeed, neither the transition to widowhood nor the transition to divorce negatively affects women’s health at any life course stage we were able to consider. Although some research indicates that marriage provides greater benefits to men than to women (Lillard and Waite 1995), our findings suggest that gender variations in the association of marriage with health reflect gender differences in the transient strains of exiting marriage and in the “honeymoon” effects of entering marriage.

Taken together, our results suggest that marriage involves a complex balance of rewards and strains. Although the benefits of entering marriage have received much attention, the initially stressful lifestyle adjustments that this transition may entail remain largely unexamined. Despite changes in gender and family roles, women continue to perform more household chores and childcare duties than men (Lennon and Rosenfield 1994). Thus, for women, becoming married may not have the same honeymoon effect as it seems to have for men, perhaps because any initial benefits are offset by strains women encounter when adjusting their expectations and lifestyles to the realities of marriage. A similar process may occur in remarriage because women typically assume the potentially stressful role of forging interpersonal bonds between members of the new “blended” family (Nielsen 1999).

CONCLUSION

Researchers should begin to question the assumptions that marriage is good for all individuals at all times and that all transitions out of marriage undermine health. Social psychologists have long recognized that personal relationships involve both rewards and strains (Rook 1984). Indeed, the negative aspects of personal relationships have stronger effects on well-being than do the positive (Rook 1984). There is little reason to believe that marriage—arguably the most intimate and salient of all personal relationships—is any different. Entering and exiting marriage can simultaneously confer both benefits and costs, and it is the delicate balance of these countervailing forces that ultimately determines how marital patterns affect health and well-being. Those who study marriage and health should begin to examine in more detail both the positive and negative aspects of marital status transitions, specify how these experiences are shaped by contextual factors (including life course stage and marital quality), and determine how these benefits and costs combine to affect men’s and women’s health. Moreover, a paradigmatic alliance of the stress process with the life course perspective (Pearlin and Skaff 1996) should continue to guide research and theory in both areas.

Biographies

Kristi Williams is Assistant Professor of Sociology at the Ohio State University. Her research examines the effects of personal relationships on mental and physical health, the mechanisms through which these effects are produced, and sociodemographic variations in these processes. Current projects focus on the effects of family labor on the health of individuals and their spouses, the impact of widowhood on health regulation, and the relative effects of marital status and marital quality on psychological well-being.

Debra Umberson is Professor and Chair of Sociology at the University of Texas. Her research focuses on structural determinants of physical and mental health, with a specific focus on gender and life course variation. Her recent research, funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA #AG17455), examines change in marital quality and the effect of marital quality on health over the life course.

Footnotes

We thank Ross Stolzenberg, Kelly Raley, Christopher Ellison, and Linda Waite for their comments and assistance. This research was supported in part by a National Institute on Aging Specialized Training Grant (2T32AG00243, University of Chicago, Center on Demography and Economics of Aging).

Using separate models to estimate (1) the effects of marital patterns between 1986 and 1989 on 1989 health and (2) the effects of marital patterns between 1989 and 1994 on 1994 health produces results that are comparable to those using the pooled data presented here. In both approaches, coefficients are of a similar magnitude and in the same direction.

A reviewer suggests that it would be useful to compare our results to those obtained from a “fixed effects model.” In regression analysis, a fixed effects model is the equivalent of an analysis of covariance model that permits each respondent to have a different constant term (intercept), but does not permit each respondent to have different coefficients for independent variables (Greene 1993). Fixed effects models are often computationally cumbersome and require ingenuity to estimate, particularly when, as in this case, the dependent variable is ordered. Further, these models are underidentified and therefore mathematically impossible to estimate in datasets involving one or two survey waves. With three survey waves, estimates of fixed effects can be calculated, but they tend to be highly unstable, with very large standard errors. Most successful applications of fixed effects models to sociological analysis involve datasets with seven or more observations (e.g., England et al. 1988).

Tables are available from the first author upon request.

- Pr (y ≥ 4 | xi) = Pr (y = 4 | xi) + Pr (y = 5 | xi), where

- Pr (y = 5 | xi) = Φ (xβ - _cut4),

- Pr (y = 4 | xi) = Pr (_cut 3 < y < _cut 4) = Φ (_cut 4 - xβ) – Φ (_cut 3 - xβ) ,

- xβ = β1x1 + β2 x2� + βixi

- xβ = (−1.577 * 1) + (.036 * 1 * (40 - 24)) + (1.335 * 1 * 0) + (−.029 * 1) * (40 - 24 * 0) + (−.005 * (40 - 24)) + (.109 * 0) + (−.004 * 0 * (40 - 24)) + (.000 * 44.386) + (−.216 * .096) + (.06 * 12.625) + (.361 * 0.646) = −.111

- Pr (y = 5 | xi) = Φ [(−.111) – (1.902)] = Φ (−2.013) = .022

- Pr (y = 4 | xi) = Φ [(1.902) – (−.111)] – Φ [(.709) – (−.111)] = Φ (2.013) – Φ (.82) = (.97778 - .79389) = .184

- Pr (y ≥ 4 | xi) =.022 + .184 = .206

- Xcross for specified W = (−b2 + b6 W) / (b4 + b7 W) , where

Controlling for Time 1 income in lagged dependent variables models is unlikely to mask true marital status and transition effects on health. By virtue of its prior causal order in the present model, Time 1 income cannot be a mechanism through which marital transitions produce changes in health.

As described by Stolzenberg (2001), the probit that corresponds to a .5 probability of reporting “excellent” or “very good” health is given by the inverse of the cumulative distribution function (c.d.f) assessed at a .5 level of probability: Ф−1 (.5) = 0. Thus, for those who experience the transition to divorce, the product of 1 and the coefficient for “married to divorced” (.435) is added to the probit: 0 + [(1)(.435)] = .435. Evaluating the normal c.d.f. at .435 gives the probability of .67, or 67 percent. As Stolzenberg (2001) notes, this function may be more succinctly given as: Φ [Φ−1 (.5) + (1 - 0) (.435)] = .67.

| Pr (y ≥| xi) md | = predicted probability that Time 2 health (controlling for Time 1 health) is “excellent or very good” among those experiencing the transition to divorce, and |

| Pr (y ≥ 4 | xi) mm | = predicted probability that Time 2 health (controlling for Time 1 health) is “excellent or very good” among the continually married. |

See the equation given in note 4.

Contributor Information

Kristi Williams, The Ohio State University.

Debra Umberson, University of Texas at Austin.

REFERENCES

- Aiken Leona S, West Stephen G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi Suzanne M, Milkie Melissa A, Sayer Liana C, Robinson John P. “Is Anyone Doing the Housework: Trends in the Gender Division of Household Labor.”. Social Forces. 2000;79:191–228. [Google Scholar]

- Booth Alan, Amato Paul R. “Divorce and Psychological Stress.”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991;32:396–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen Laura. “Social and Emotional Patterns in Adulthood: Support for Socioemotional Selectivity Theory.”. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:331–338. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder Glen. Life Course Dynamics: Trajectories and Transitions 1968–1980. New York: Cornell University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- England Paula, Stanek Kilbourne Barbara, Farkas George, Dou Thomas. “Explaining Occupational Sex Segregation and Wages: Findings from a Model with Fixed Effects.”. American Sociological Review. 1988;53:544–558. [Google Scholar]

- Ensel Walter M, Lin Nan. “Age, the Stress Process, and Physical Disease.”. Journal of Aging and Health. 2000;12(2):139–168. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensel Walter M, Kristen Peek M, Lin Nan, Lai Gina. “Stress in the Life Course: A Life History Approach.”. Journal of Aging and Health. 1996;8(3):389–416. doi: 10.1177/089826439600800305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro Kenneth F, Farmer Melissa M. “Utility of Health Data from Social Surveys: Is There a Gold Standard for Measuring Morbidity?”. American Sociological Review. 1999;64(2):303–315. [Google Scholar]

- George Linda K. “Sociological Perspectives on Life Transitions.”. Annual Review of Sociology. 1993;19:353–373. [Google Scholar]

- Greene William H. Econometric Analysis. Upper Saddle River. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hemstrom Orjan. “Is Marriage Dissolution Linked to Differences in Mortality Risks for Men and Women?”. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:366–378. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz Allan V, Raskin White Helene. “Becoming Married, Depression, and Alcohol Problems Among Young Adults.”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991;32:221–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House James S. American’s Changing Lives: Wave I [Electronic Data Tape] Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [Distributor]; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C, Greenberg David F. Linear Panel Analysis: Models of Quantitative Change. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon Mary Clare, Rosenfield Sarah. “Relative Fairness and the Division of Housework: The Importance of Options.”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1994;100:506–531. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard Lee A, Waite Linda J. “Till Death Do Us Part: Marital Disruption and Mortality.”. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;100:1131–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Long J Scott, Freese Jeremy. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables in STATA. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marks Nadine, Lambert James. “Marital Status Continuity and Change Among Young and Midlife Adults: Longitudinal Effects on Psychological Well-Being.”. Journal of Family Issues. 1998;19:652–687. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr. “Psychological Resilience Among Widowed Men and Women: A 10-Year Follow Up of a National Sample.”. In: Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hansson RO, editors. Handbook of Bereavement. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1993. pp. 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. “Age and Depression.”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1992;33:187–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen Phyllis. “Gender, Aging, and the Life Course.”. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. New York: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 171–187. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen Linda. “Stepmothers: Why So Much Stress? A Review of the Research.”. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage. 1999;30(1–2):115–148. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I, McKean Skaff Marilyn. “Stress and the Life Course: A Paradigmatic Alliance.”. The Gerontologist. 1996;36(2):239–247. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers Richard G. “Marriage, Sex, and Mortality.”. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Rook Karen. “The Negative Side of Social Interaction: Impact on Psychological Well-Being.”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:1097–1108. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E, Mirowsky John, Goldsteen Karen. “The Impact of Family on Health: The Decade in Review.”. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:1059–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Simon Robin W. “The Meanings Individuals Attach to Role Identities and Their Implications for Mental Health.”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:256–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon Robin W, Kristin Marcussen. “Marital Transitions, Marital Beliefs, and Mental Health.”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:111–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolzenberg Ross M. “It’s about Time and Gender: Spousal Employment and Health.”. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;107(1):61–100. doi: 10.1086/323151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits Peggy. “Stress, Coping, and Social Support Processes: Where Are We? What Next?”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;(Extra Issue):53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbrich Patricia M, Warheit George J, Zimmerman Rick S. “Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Psychological Distress: An Examination of Differential Vulnerability.”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30:131–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra. “Gender, Marital Status, and the Social Control of Health Behavior.”. Social Science and Medicine. 1992;34(8):907–917. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90259-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Wortman Camille B, Kessler Ronald C. “Widowhood and Depression: Explaining Long-Term Gender Differences in Vulnerability.”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1992;33(1):10–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton Blair. “Life Transitions, Role Histories, and Mental Health.”. American Sociological Review. 1990;55:209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Williams David R, Takeuchi David T, Adair Russell K. “Marital Status and Psychiatric Disorders among Blacks and Whites.”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1992;33:140–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]