Abstract

Background:

Patients with multiple sclerosis experience hospitalization several times in their lives. Certainly, providing efficient and high-quality care by healthcare professionals is not possible unless the experiences of patients’ hospitalization are taken into consideration. This qualitative study was aimed to identify experiences of patients with multiple sclerosis in their hospitalization.

Materials and Methods:

A qualitative content analysis method was used to conduct this study. The study participants were 25 patients with multiple sclerosis, who were chosen by purposeful sampling. Data were collected through non-structured interviews.

Results:

The analysis resulted in the emergence of 4 themes and 11 subthemes. The main themes were: Religiosity, emotional reactions, seeking support, and feeling of being in a cage.

Conclusions:

Awareness of families and healthcare providers of the reactions of patients with multiple sclerosis to hospitalization will help them to deal effectively with patients and to improve relationships with them. However, by understanding the patients’ experiences, the practitioners gain expertise and can join in the patients’ health journey in a therapeutic way during the hospitalization period. In addition, the findings can serve to create a framework for developing nursing care processes including informational and supporting programs for multiple sclerosis patients during hospitalization while taking into consideration patients’ needs and cultural backgrounds.

Keywords: Content analysis, hospitalization, multiple sclerosis

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) affects more than 2.5 million people worldwide,[1] and around 60,000 people in Iran currently live with the disease.[2] MS is a complex disease with variable presentation and an unpredictable prognosis and time course.[3] However, following the first clinical episode of MS, 80% of patients experience a relapsing remitting type of MS. Therefore, after the first hospitalization for diagnosis of MS, patients usually experience hospitalization several times due to repeated attacks of the disease.[4] On average, 42% of MS patients, after a 20-year period, enter the secondary progressive phase. Over time, around 65% of patients with MS enter the secondary progressive phase[5] and certainly experience hospitalization several times.[6] Two-thirds of diagnoses of MS occur between the ages of 20 and 40,[7] and this early onset, the high disability, frequent hospitalizations and the costs associated them, and treatment have an impact on individuals, families, the healthcare system, and society.[8] Over a 6-month period, the average overall cost for a patient with MS is £8397, much of which is related to the cost of hospitalization.[9] About one-quarter of people with MS need comprehensive long-term care during the course of their disease, including a continuum of rehabilitative, therapeutic, and supportive care, and hospitalization.[10] Patients with MS have significantly higher rates of contacts with the healthcare system, which includes all healthcare sectors: General practice, outpatient clinics, and in-hospital services;[4] therefore, it is vital for those involved in care and treatment to know what characteristics does high-quality care encompass – not just the technical features but also in terms of the experiences of patients.[6] Health professionals can better serve patients when they recognize the patients’ personal experiences of their illnesses and when they heed the particular concerns and possible impacts of the hospital setting on the patients’ chronic conditions.[11] Not only the physical symptoms associated with MS, but also psychological (depression, anxiety, etc.) and cognitive (memory impairment, impaired learning and concentration) disorders have a high prevalence in patients.[9] Also, the view of the society toward MS is quite different from that of other chronic diseases; in fact, MS is associated with inappropriate social label.[4] These problems may affect the mental ability and rational inferences and reasoning of patients. These issues are less common in other chronic diseases; therefore, the patients’ experiences when interacting with others (family, healthcare professionals, etc.) and the surrounding environment will be different. Certainly, being aware of the patients’ experiences about hospitalization will affect the quality of care of healthcare professionals.[4,9] The patients’ experiences of hospitalization can provide nurses with a deeper understanding and knowledge of the work that they should do.[11] The effects of high cost and problems of hospitalization on patients and families make caregivers and therapists to care for patients based on their needs and with high quality.[11,12] Chou et al., Ekdahl et al., and Andenes et al. have pointed out in their reports that certainly, providing efficient and high-quality care by healthcare professionals is not possible unless the experiences of patients about their hospitalization are taken into consideration.[12,13,14] The study conducted by Hughes et al. revealed that for many patients and families, one of the most frightening features of the experience of chronic illness was being hospitalized.[15] According to the studies of Koenig et al., Siemens, and Ekdahl et al., care at hospital did not seem to be planned for patients with chronic disease, and exploring the experiences of patients and their families of care and hospitalization is necessary to design a comprehensive care model for the chronic patients at hospital.[11,12,16] Hospital care professionals have to pay more attention to patients’ experiences to promote their competencies in caring for them with high quality in the hospital. People with MS are a very important group of patients to focus on, due to their rising number and rising economic impact on healthcare costs, and owing to the challenge of adjusting the hospital care system to meet the needs of these patients. Little is known about the experiences of MS patients in their care, who face expanded disabilities and different symptoms during hospitalization.[17] This study will contribute to research in this area. The aim of the present study is to explore the experiences of hospitalization among the MS patients. No studies have been was done to explore the MS patients’ experiences of hospitalization in Iran. So, it seemed not only valuable, but also critical to investigate the hospitalization experiences of patients with MS within the Iranian cultural context. A decision was made to conduct a qualitative study regarding the most suitable method[18] for determining the deepening perception of MS patients’ experiences of hospitalization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

A qualitative study with a content analysis approach was used to investigate MS patients’ experience of hospitalization. Qualitative research aims to explore the complex phenomena that are encountered by clinicians, healthcare providers, policy-makers, and consumers in the healthcare system.[19] It can be an important tool in understanding the emotions and perceptions, while health policies can be developed through this type of research.[20] Content analysis is a research method for making replicable and valid inferences from data to their context, with the purpose of providing knowledge, new insights, a representation of facts, and a practical guide to action.[21] It should be mentioned that qualitative studies of patients’ perspectives would be needed to identify the needs and feelings behind identity formation during their hospitalization. In nursing research, content analysis is an essential way to provide evidence of a phenomenon, while qualitative research is considered to be the only way for the same purpose, especially in sensitive topics.[21] Content analysis is a systematic coding and categorizing approach that can be used to explore unobtrusively a large amount of textual information in order to ascertain the trends and patterns of communication.[22] This is perhaps the most common approach used in the qualitative research that has been reported in health journals. It aims to present the key elements of the respondents’ accounts. It is a useful approach for answering questions about the salient issues for particular groups of respondents or for identifying the typical responses.[23] According to the above, a decision was made to conduct a qualitative study with a content analysis approach for understanding the emotions and perceptions of MS patients about hospitalization as a complicated phenomenon (Polit and Beck 2008).[18]

Participants

The participants in this study were 25 patients (18 females and 7 males) who had been suffering from MS for 4-18 years. They were selected by an objective sampling method from the neurologic centers of hospitals and the MS associations of Isfahan and Tehran (Iran). The inclusion criteria were patients having a history of diagnosed MS, history of hospitalization due to MS ≥ 2, no problem in hearing and speaking, willingness to share experiences, and those with no history of other pathological or chronic diseases. The researchers tried to include participants of different ages, sexes, duration of having MS, and frequency of hospitalization to help transferability of findings.

Ethical considerations

The ethics committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences approved the research proposal. Participants were asked to sign an informed consent before their inclusion in the study. They were reassured of the confidentiality and anonymity of the study; they were told that the participation was voluntary and they could refuse to participate or withdraw from the study without any penalty. Moreover, participants were reassured that their responses would be kept confidential and their identities would be protected and not published in research reports or in the published findings.

Data collection

The data were collected through unstructured interviews from September 2011 to August 2012. Each interview lasted 40-80 min. The place of the interview was selected according to the participants’ wishes. Each participant was interviewed one or two times. The initially developed interview guide consisted of a number of open-ended questions, for example, “Would you please explain your most recent hospitalization for me?” “How was hospitalization for you?” Participants were encouraged to speak openly and relate their personal experiences of hospitalization. As part of the data collection process, field notes were also used. Data gathering continued to the level of saturation. Data saturation occurred when a code or new category did not emerge from data analysis.[19] In this study, a saturation point was reached when no new data or category emerged following the interview with the 21st participant.

Data analysis

The interview texts were analyzed by using qualitative content analysis in accordance with Granehim and Lundman.[24] In this way, the recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim, and then reviewed several times in order to obtain a sense of the whole. The first author subsequently extracted units of analysis. The text was divided into condensed meaning units that were abstracted and labeled with a code. After that, the various codes were compared based on the differences and similarities, and sorted into categories and subcategories which made up the manifest content. The tentative categories were discussed by three researchers and revised. Finally, the underlying meaning, or the latent content of the categories, was formulated into themes. The following steps were followed to analyze the data[24]:

Transcribing the interviews verbatim and reading through them several times to obtain a more complete sense of the whole

Dividing the text into meaning units that were condensed

Abstracting the condensed meaning units and labeling with codes

Sorting the codes into subcategories and categories based on comparisons regarding their similarities and differences

Formulating themes as the expression of the latent content of the text.

Validity and reliability/rigor

Validation of emerging codes and categories in subsequent interviews was done along with debriefing by two supervisors. The conformability and credibility of the findings underwent verification through member checking, peer checking, and maximum sampling variation in terms of age, sex, education, and so on. To create inter-transcript reliability, two experts conducted the second reviewing process. About 70% of the transcripts underwent revision to the point at which the study team expressed strong agreement. To reach a conclusive decision, disagreements underwent modification through discussion.

RESULTS

Participants in this study were 25 patients with the following profile: 18 women and 7 men, with a mean age of 32 years and mean of 10 years experience of disease; 2 patients with Master's degree of education, 6 with Bachelor's degree, 4 with Associate degree, 8 with diploma, and 5 had under diploma education; 17 patients were married and 8 patients were single. All participants were Muslims and had a history of hospitalization due to MS ≥ 2.

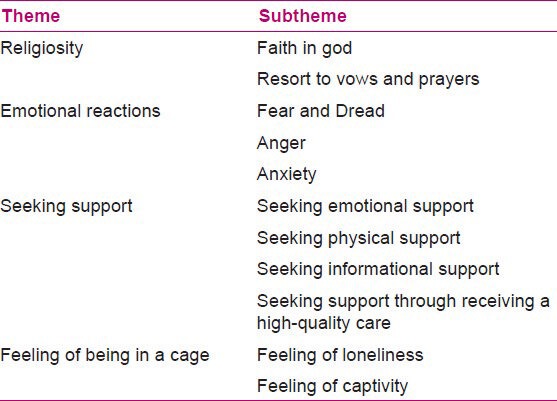

During the data analysis, 4 main themes and 11 subthemes emerged from hospitalization experienced by patients with MS [Table 1].

Table 1.

Hospitalization experiences by patients with MS

Religiosity

Religiosity, in its broadest sense, is a comprehensive sociological term used to refer to the numerous aspects of religious activity, dedication, and belief.[25] This theme was composed of two subthemes: faith in God and resort to vows and prayers.

Faith in God

Participants considered faith in God as an effective factor in comfort during hospitalization:

P19: “In difficult times of hospitalization, I trusted God and begged him to let my eyes recover.” (Female aged 47).

Resort to vows and prayers

Most participants had told their families to bring them prayer books and had vowed to get rid of the disease and the hospital.

P8: “I constantly recite prayers I had vowed to sacrifice a sheep for orphans if I was discharged from hospital soon and on my feet.” (Female aged 30).

Emotional reactions

Everyone's initial reaction on being diagnosed with MS is different – whatever he/she is experiencing, whether it's shock, fear, denial, anxiety, or anger (or some combination of all of these) – but these reactions are normal, and patients and their caregivers would re-experience some variation of them whenever MS brings new symptoms and challenges into their life.[23]

Fear and dread

Some of the participants had experienced hospitalization as a horrible period.

P1: “When I was in hospital, it was the worst day of my life. I was afraid of everything – paralysis, staying in hospital, other patients screaming, etc.” (Female aged 36).

Anger

Some participants were aggressive and anxious in their first experience of hospitalization, but in the subsequent times, this feeling became less.

P5: “During hospitalization, especially the first time, I was very angry toward myself, my family, and medical staff. I couldn’t stand anyone, and I lost my temper quickly, in just a few short minutes.” (Male aged 26).

Anxiety

Participants had experienced considerable concerns such as lack of improvement or worsening, hospital costs, and the loneliness of their children. However, women were more concerned about the children.

P12: “I was very concerned about the hospital costs. You would not believe that I was so anxious about the costs that I did not think about anything else.” (Male aged 35).

P8: “In the hospital, I was always worried about my 6-month-old daughter. She needed milk and my love. I was worried that she might become sick.” (Female aged 30).

P7: “I was worried that I would not be able to walk anymore, I was afraid of losing my sight forever. It was a very bad time!” (Female aged 31).

Seeking support

Participants experienced the need for emotional and physical support from family, friends, and healthcare professionals.

Seeking emotional support

Participants looked for emotional support from nurses, doctors, and family during hospitalization. In their opinion, empathy and compassion, ensuring and giving hope, good behavior, listening well, honesty, establishing eye contact, and respectful approaches were some of the most important supportive behaviors expected from nurses and doctors.

P8: “One day when I was crying, a nurse held my hand for a few minutes and stayed with me. She listened to me, I needed sympathy, empathy, and reassurance; she gave all these things to me.” (Female aged 30).

P11: “It was so good that during the rough times of my hospitalization, the nurses gave me hope for the future.” (Female aged 24).

P10: “As soon as my mother sat by my bedside, I felt the greatest sense of peace and confidence. In the hospital, I was so hungry for the kindness of my family.” (Female aged 29).

Based on the participants’ experiences, it was revealed that doctors were not responsive to patients’ emotional needs.

P5: “When the doctor came over to me, he did not even look at me. I wanted him to listen to me or talk to me, but unfortunately he just explained the future of my disease so negatively.” (Male aged 26).

Seeking physical support

A majority of the participants were hospitalized because of the numbness in limbs or eyesight problems. Actually, they were in great need of physical assistance of caregivers and families.

P6: “In the hospital, I needed the help of nurses or my family for doing my personal tasks like going to toilet or dressing; my daughter and my husband stayed with me in turns and helped me, but most of nurses did not help.” (Female aged 40).

Seeking informational support

P17: “Some nurses give necessary training in a pleasant way and it is so nice that there would always somebody that you could address your questions to, especially in the terrifying environment of the hospital!” (Male aged 27).

Most participants were satisfied with the nurses’ training, but they mentioned that they did not receive any education from doctors.

P7: “Doctors did not teach me anything and just wrote down medication orders. I could not be certain about my medications because I did not know anything about them.” (Female aged 31)

Seeking support through receiving high-quality care

Participants were willing to get high-quality care during hospitalization; they understood it as a kind of support from caregivers and therapists. But unfortunately, some of them did not receive proper care and believed that they were not supported by sufficient care at hospital.

P22: “I wanted to go to the bathroom, so I called the nurse but she did not come. I did not have any companion; I had to go alone with numbness in my feet and serum in my hand. I had a severe fall.” (Female aged 42).

Researchers’ observation was as follows

A young girl asked for help from the nurses because of incontinency. A middle-aged nurse came to her reluctantly, as she was scolding her. The young girl remained crying silently.

Feeling of being in a cage

Some participants have likened the hospital to being in a cage because in the hospital, they felt loneliness and captivity. Moreover, they were not allowed to leave the hospital.

P13: “Being in the hospital was like being in a cage. Just injections and medication, I would have loved to go out in those spring days, see the flowers and breathe fresh air, but I had to stay in a cage alone.” (Male aged 32).

P10: “15 days being in a bed with serum injected in my hand bored me; I did not feel like talking to anyone. I was like a bird in a cage, alone and captured.” (Female aged 24).

DISCUSSION

Findings of this study share similarities and differences with other studies in terms of experiences of hospitalization of patients with MS and other chronic diseases. Similar to Hughes's (2004) study, in the present study also, the participants pointed to God and resorted to prayer during hospitalization.[15] In the present study, patients’ religious faith caused positive acceptance of hospitalization. Various researchers have suggested that religiosity is related to better adjustment to painful condition, such as being confronted with chronic disease and hospitalization.[15,16] Religiosity provided an avenue to view the illness experience differently. Considering the fact that most of the Iranian population (about 98%) is Muslim and that a religious culture is dominant, religious beliefs are expected to play an important role in daily life, especially in the face of a crisis.[25] More than 80% of the studies have established that religion plays an important role in providing mental and physical health, especially the fact that religious beliefs and practices decrease the feeling of lack of control over chronic diseases and their frustrating treatments and hospitalization.[26,27] Similar to a study by Andenes et al., participants in this study experienced emotional reactions to hospitalization that included fear and dread, anger, and anxiety.[14] Anger toward oneself, family, and healthcare personnel was a reaction that some of the participants showed at the hospital. In a study by Westbrook and Viney, 126 patients with chronic disease interviewed during hospitalization were found to be experiencing considerable emotional reactions. Multivariate analysis of variance indicated that patients experienced significantly more anxiety, fear, depression, and directly and indirectly expressed anger as well as positive feelings, and that they perceived themselves to be more helpless.[28] Most participants in this study had experienced anxiety at the hospital; this concern was due to loneliness of the patient's husband and children at home, the high cost of medication and hospitalization, and also the anxiety of possible disability after discharge. Similarly, in the study of Boutin-Foster, many participants with coronary artery disease who had experience with prior hospitalizations described their previous experience as an emotionally stressful period filled with worry about who would care for their family in their absence.[29] When social networks volunteered to take care of family members such as a child or a spouse, it was perceived as being helpful.[4,30] In this study, participants were seeking emotional, physical, informational, and caring support. They emphasized the emotional and physical support of their families, friends, and healthcare professionals during hospitalization. Studies of Siemens and Ekdahl et al. confirmed the finding that the patients with rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and other chronic diseases were constantly searching for physical and emotional support during hospitalization.[11,12] Siemens and Chou et al. reported that patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Parkinson's had mentioned that the more emotional and physical support they receive from family, friends, and healthcare professionals, the easier is the acceptance of painful conditions of hospitalization.[11,13] Participants emphasized that they needed attention, understanding, empathy, and sympathy to adapt to the daunting condition of hospital. Unfortunately, most participants in this study felt dissatisfaction with them, particularly doctors. This was cited as a cause for distrust of medical personnel, resulting in the number of participants insisting on being discharged earlier. Certainly, lack of confidence in the therapy and therapist will have irreversible consequences for the patient. According to Buecken et al., healthcare professionals can be an important resource of support. They could be good listeners and provide information, knowledge, sympathy, empathy, and encouragement for patients.[10] Krokavcova et al. supposed that MS patients rely on the neurologists in a confidential relationship. The feeling of confidence in patients can significantly reduce the effects of stress experiences on their physical and psychological outcomes.[31] Participants in this study often had expected to receive care and informational support from healthcare professionals, and knew them as being responsible for that support. Unfortunately, in some cases, participants had not received sufficient information from healthcare professionals, especially doctors. However, similar to the findings of Roebuck et al., patients after myocardial infarction (MI) expressed that they had limited understanding of their disease and medications and wanted to know more. Since lack of understanding generates concerns about the potential side effects of disease and medications, support from formal carers in terms of information is significant during hospitalization, also after discharge.[32] Most participants were dissatisfied with the care at the hospital. Chou et al. explored the current practices and opinions regarding hospital management of Parkinson's disease (PD) patients in specialized PD centers. Their findings showed that most centers were not confident about the quality of PD-specific care provided to their patients when hospitalized.[13] Most participants had experienced being in the hospital similar to being in a cage. They felt bored and lonely in the hospital. Lack of independence in activities at hospital, the unfamiliar hospital environment, being away from home and family, and having to stay at hospital, all affected the patients’ perception of the hospital and made them think of it as dark, narrow, and cage-like. The methods in this study were used to improve the strength (rigor) of this study, but some limitations were inherent. The sample size was small, and the context was confined to a particular geographic location. To ensure the greatest benefit from healthcare expenditures and to provide good-quality health care, future research and medical education should focus on the challenges of adjusting the hospital care system to meet the needs of these patients.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study revealed the reactions and needs experienced by patients with MS during hospitalization. Awareness of families and healthcare providers of the reactions of patients to hospitalization will help them to deal effectively with the patients and to improve relationships with them. Participants experienced the need for emotional support, the need for information about their treatment and medication, and the need for receiving high-quality care at hospital. Our findings revealed that patients had some expectations of families, doctors, and nurses that, perhaps, these people were not aware of. So, awareness of these experiences among the family members and, especially, care and treatment team will help them to design a comprehensive care model for MS patients during hospitalization.

Implications for practice

However, by engaging the patients’ experiences, practitioners gain expertise and can join in the patient's health journey in a therapeutic way during the hospitalization period. Conceptualizing caring practice in this way constitutes an awareness of the therapeutic or healing value of understanding and being understood. We expect that the findings will give nurses and other healthcare professionals a deeper perception of how to care for patients with MS with high quality and help them to adapt to hospitalization. In addition, the findings can serve to create a framework for developing nursing care processes including informational and supporting programs for MS patients during hospitalization, while taking into consideration patients’ needs and cultural backgrounds.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely appreciate all participants who cooperated with us in conducting this study. We thank the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR), neurology centers, and MS Society of Tehran and Isfahan (Iran) for their support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This paper is a part of the first author's (Ghafari) thesis for PhD degree of nursing that has been funded and approved by the research administration of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR), Tehran, Iran

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.National MS Society. Who gets MS? 2011. [Last accessed on 2012 Nov 17]. Available from: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/about-multiple-sclerosis/who-gets-ms/index.aspx .

- 2.Etemadifar M, Sahraiyan MA. Increasing of MS prevalence in Iran. 2012. [Last accessed on 2012 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.iranms.ir .

- 3.Clarke CE, Howard R, Rosser M, Shorvon S. London: Wiley Blackwell; 2009. Neurology a queen square textbook. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jennum P, Wanscher B, Frederiksen J, Kjellberg J. The socioeconomic consequences of multiple sclerosis: A controlled national study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Compston A, Coles A. Multiple Sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 2006;332:525–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7540.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naci H, Fleurence R, Birt J, Duhig A. Economic burden of multiple sclerosis: A systematic review of literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28:363–79. doi: 10.2165/11532230-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patwardhan MB, Matchar DB, Samsa GP, McCrory DC, Williams RG, Li TT. Cost of multiple sclerosis by level of disability: A review of the literature. Mult Scler. 2005;11:232–9. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1137oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCrone P, Heslin M, Knapp M, Bull P, Thompson A. Multiple sclerosis in the UK: Service use, costs, quality of life and disability. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:847–60. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826100-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buecken R, Galushko M, Golla H, Strupp J, Hahn M, Ernstmann N, et al. Patients feeling severely affected by multiple sclerosis: How do patients want to communicate about end-of-life issues? Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88:318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siemens VM. The experience of hospitalization for orthopedic surgery: Individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. J Orthop Nurs. 2001;5:142–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ekdahl WA, Andersson L, Friedrichsen M. “They do what they think is the best for me.” Frail elderly patients’ preferences for participation in their care during hospitalization. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:233–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou KL, Zamudio J, Schmidt P, Price CC, Parashos SA, Bloem BR, et al. Hospitalization in Parkinson disease: A survey of National Parkinson Foundation Centers. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:440–5. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andenaes R, Kalfoss MH, Wahl AK. Coping and psychological distress in hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung. 2006;35:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes WJ, Tomlinson A, Blumenthal AJ, Davidson J, Sketch HM, Watkins HL. Social support and religiosity as coping strategies for anxiety in hospitalized cardiac patients. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28:179–85. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2803_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koenig HG, George LK, Titus P. Religion, spirituality, and health in medically ill hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:554–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchanan RJ, Radin D, Huang CH. Caregiver perceptions associated with risk of nursing home admission for people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Health J. 2010;3:117–24. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polit D, Beck T. 8th ed. London: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008. Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holloway I. 1st ed. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press; 2005. Qualitative research in health care. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gbrich C. 1st ed. London: Sage; 2007. Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green J, Thorogood N. 1st ed. London: Sage; 2004. Qualitative methods for health research. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassankhani H, Taleghani F, Mills J, Birks M, Francis K, Ahmadi F. Being hopeful and continuing to move ahead: Religious coping in Iranian chemical warfare poisoned veterans, a qualitative study. J Relig Health. 2010;49:311–21. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9252-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janssens AC, Doorn PA, Boer JB, Meché FG, Passchier J, Hintzen RQ. Impact of recently diagnosed multiple sclerosis on Quality of life, anxiety, depression and distress of patients and partners. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;108:389–95. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choumanova I, Wanat S, Barrett R, Koopman C. Religion and spirituality in coping with breast cancer: Perspectives of Chilean women. Breast J. 2006;12:349–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westbrook MT, Viney LL. Psychological reactions to the onset of chronic illness. Soc Sci Med. 2005;16:899–905. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boutin-Foster C. Getting to the heart of social support: A qualitative analysis of the types of instrumental support that are most helpful in motivating cardiac risk factor modification. Heart Lung. 2005;34:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilden MD, Kubisiak J, Zbrozek A. The economic burden of Medicare-eligible patients by multiple sclerosis type. Value Health. 2011;14:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krokavcova M, van Dijk JP, Nagyova I, Rosenberger J, Gavelova M, Middel B, et al. Social support as a predictor of perceived health status in patients with multiple sclerosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roebuck A, Furze G, Thompson DR. Health-related quality of life after myocardial infarction: An interview study. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34:787–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]