Abstract

Background:

Quality of life (QOL) is a multidimensional concept which has nowadays turned to a supportive interventional goal in chronic diseases like cancer. Numerous interventions have been carried out to improve the QOL in patients with cancer, but the effect of indirect interventions on the patients’ QOL has not been investigated yet. This study aimed to compare the efficacy of group meaning centered hope therapy of cancer patients and their families on the patients’ QOL.

Materials and Methods:

This is a clinical trial conducted in three groups with a pre-test post-test design in which the effect of independent variable of meaning centered hope therapy on the dependent variable of QOL was investigated. The subjects were selected from the cancer patients who were aware of their diagnosis, were in primary stages of the disease, and had passed one period of chemotherapy. In this study, 42 patients (16 in control group, 14 in patients’ group therapy, and 12 in patients’ families’ group therapy) were studied, and WHOQOL was adopted to investigate their QOL. Data were analyzed in two forms of descriptive and inferential statistical tests.

Results:

The results obtained showed that group meaning centered hope therapy of cancer patients and their families had a positive effect on patients’ QOL compared to the control group. The notable finding of the present study was that holding group sessions either for the patients or for their families equally improved patients’ QOL.

Conclusion:

QOL of the cancer patients can be improved by either group meaning centered hope therapy for patients or group meaning centered hope therapy for their families. This finding is important for therapists, as when the patients cannot attend group therapy sessions due to complications of chemotherapy, these sessions can be held for their families to improve patients’ QOL. This conclusion is very helpful in nurses’ interaction with the patients and their families.

Keywords: Cancer, caregivers, hope therapy, Iran, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Getting informed about the diagnosis of cancer is a miserable and unexpected experience for everybody. The psychological impact of cancer diagnosis and its physical complications negatively affects the quality of life (QOL) of the patients and their families.[1] QOL is a multidimensional concept including subjective and objective factors,[2] and often refers to personal concept of satisfaction with life, physical health, social and familial health, hope, and mental health. Investigation of QOL has changed to a variable associated with clinical care in the research.[3] There are numerous methods to improve the QOL among cancer patients, including group psychotherapy interventional methods. Psychotherapy methods resulting in promotion of hope among the patients lead to improvement of their QOL. Among these methods, hope therapy has the main goal of promoting hope among the patients.[4] As these patients usually think that cancer equals death, they develop problems in understanding the meaning and values of their life. A mere solution-centered treatment does not seem to help these patients. Therefore, in order to promote hope therapy sessions and increase their efficacy, it is better to practice them with an existential approach like meaning therapy.[5] Numerous studies have been already conducted to help cancer patients lower their disease-related complications. These studies include the effect of mindfulness on cancer patients’ mood,[6] the effect of combined psychotherapy on cancer patients’ QOL,[7] the effect of spirituality, psychotherapy, and music in the palliative care of cancer patients, the effect of group meaning therapy on cancer patients’ life expectancy,[3] etc. Literature review revealed no study concerning the effect of group meaning centered hope therapy (combination of hope therapy and meaning therapy) on cancer patients and their families and comparison of this effect on patients’ QOL. In most of the reviewed articles, patients’ problems were investigated and not those of their families, although social support of the families has been reported very impressive on patients’ recovery trend[8] in the existing references. In addition, when the patients are in the phase of denial or anger due to their disease, they may not cooperate enough with the treatment team, especially nurses. In these cases, if hope therapy on the patients’ families can have an equal effect as patients’ own hope therapy, psychological interventions on the family members can replace those of the patients. With regard to the above-mentioned challenges, the main goal of this study was to compare the effect of group meaning centered hope therapy in the families compared to the group meaning centered hope therapy in patients on the patients’ QOL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a clinical trial conducted to investigate the effect of the independent variable of meaning-centered hope therapy on the dependent variable of QOL.

This is a three-group pre-test post-test design with a control group, in which group meaning centered hope therapy sessions were held for both the groups of patients and their families. In group 3 (control group), just conventional interventions were administered. In all three groups, patients’ QOL was compared before and after the intervention. Research environment was Seyed Al-Shohada Hospital in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran, which is a professional center for cancer patients in Isfahan province. The subjects were the cancer patients referring to the research environment during Sept-Oct. 2012 who met the inclusion criteria including knowing about their diagnosis of cancer, being in primary stages of the disease, and having passed through at least one period of chemotherapy. Then, the patients and their family caregivers were randomly assigned to the control and study groups. Exclusion criteria were any diagnosed metastasis and patients affected by dementia and other psychotic conditions. Based on similar related researches and their sample sizes, and after consultation with one of the professors of statistics in the university, the sample size in this clinical trial study was calculated to be 16 subjects in each group to achieve an accuracy of 95%, a power of 0.8, and standard deviation (SD) of QOL score of 10. Data were collected by a personal characteristics questionnaire with eight questions and a World Health Organization's Quality Of Life questionnaire (WHOQOL) including 26 items scored with a five-point Likert's scale (scores 1-5), and were standardized in Iran by Yousefi et al.[9] These questionnaires were given to the subjects before and after the group sessions, and the subjects were asked to fill them up and return to the researcher on the same day. Group meaning centered hope therapy was administered in eight 90-min weekly sessions for the patients and their families (n = 14 in patients group therapy and n = 12 in patients’ family group therapy). This is a combination of hope therapy and meaning therapy sessions presented by Sotoudeh and Mehrabizadeh. In the first intervention session, the patients were familiarized with the principles of meaning-centered hope therapy and its application in daily life. Theoretical bases of QOL and cancer were described to the patients, and each subject was asked to tell the story of his/her disease with emphasis on the level and manner of its effect on his/her QOL, and then, the principle of free will was emphasized. In the second session, the association between patients’ QOL on the one hand and hope, meaning, attitude values, experimental and innovative values on the other hand was emphasized. In the third and fourth sessions, experimental attitude and ethical values and their roles in the formation of hopeful thinking and finding the meaning were discussed in depth. In the fifth and sixth sessions, it was explained that as everybody is responsible for his/her past and future life, one should set goals with regard to the innovative values and plans to access them. In other words, three components of Schneider's theory (goals, factor, and pathways) should be considered. At this stage, patients were asked to state any example of hope from their life. Then, subjects’ past success was used to detect and empower their hope components in life accordingly. The specifications of appropriate goal setting to improve patients’ QOL were discussed, and the patients were asked to determine goals for each of the above-mentioned cases. In the seventh session, the formula of “hope = goal + will power + patience + planning power + detection of obstacles in the achievement of goal + coping mechanisms” was introduced. The patients were asked to practice and make imaginations about regulating and the way of achieving goals. In the last session, a feedback was taken from the group, and they were helped to conclude that we are responsible for the world we make, out of the conditions we are in.[2,10] Data were analyzed by deceptive and inferential statistical tests through SPSS14. The statistical tests adopted in the present study were as follows:

Statistical description of data including subjects’ demographic characteristics, central statistical indexes (mean), and distribution including SD and differences in pre-test post-test scores

To investigate the difference between the study and control groups, firstly, covariance analysis was tried. But due to lack of prerequisites of this test [uncorrelated covariate (s) with other independent variables and linear relationship between the covariate (s) and the dependent variable], calculation of before-after differences of QOL scores and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were adopted

Scheffe post-hoc test was used to compare the efficacy of pair interventions. Ethical considerations have been fully considered by the researchers and approved by Iranian Islamic Azad University.

RESULTS

In the present study, 42 patients (16 in the control group, 14 in patients’ group therapy, and 12 in patients’ family group therapy) attended, of whom 69% were females and 31% were males. Subjects’ mean age was 44 years. With regard to the etiology of the disease, 19% had lymphoma, 31% had gastrointestinal cancers, 38.1% women had related cancers, and 11.9% had other types of cancers. About 31% underwent just chemotherapy and 69% had combined treatment, like a surgery and radiotherapy.

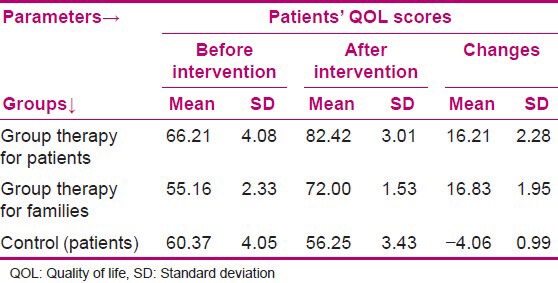

After administration of the interventions and filling up of the questionnaires, the following results [Table 1] were obtained.

Table 1.

Comparison of patients’ QOL changes

One-way ANOVA showed a significant difference in the QOL score changes between the three groups (P < 0.01, f = 48.09).

With regard to the hypothesis of the effect of group meaning centered hope therapy in patients on their QOL, the results showed a significant difference in the patients’ QOL changes in the patient and control groups. After one-way ANOVA, Scheffe post-hoc test results were used (changes in mean differences in the two groups = 20.27 and P < 0.01).

As the first question of QOL questionnaire was about subjects’ viewpoints about their QOL (how do you evaluate your QOL?), in addition to patients’ general QOL, this question was also considered. As data of answers to the first question have been reported as ordinal data, Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric equivalence of ANOVA) was used and showed a significant difference in patients’ QOL changes between the patients’ group and the control group from their viewpoints (Chi = 20.91, P < 0.01).

On investigating the hypothesis concerning the effect of group meaning centered hope therapy in the families on the patients’ QOL, the results showed a significant difference in patients’ QOL changes between family and control groups. Scheffe post-hoc test was used after one-way ANOVA (changes in mean differences in the two groups = 20.89, P < 0.01). The first question of the questionnaire was tested by Kruskal-Wallis test and showed a significant difference in the patients’ QOL changes from the viewpoints of family and control groups (Chi = 17.73, P < 0.01).

Another finding obtained by Scheffe and Kruskal-Wallis tests showed the effect of group meaning centered hope therapy in patients compared to group meaning centered hope therapy in families on patients’ QOL. Results showed no significant difference in patients’ QOL changes between patient and family groups, revealing an identical effect on patients’ QOL due to group meaning centered hope therapy in patients and group meaning centered hope therapy in families (Scheffe test results: Changes in mean differences in the two groups = 6.19 ± 2.59, P > 0.91). Separately testing questionnaire's first question through Kruskal-Wallis test showed no significant difference in the patients’ QOL changes in the patient and family groups too (Chi = 3.36, P > 0.46), revealing that group intervention administered either for the patients or for their families had an identical effect on patients’ QOL from their viewpoints.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to investigate the efficacy of group meaning centered hope therapy of cancer patients and their families on the patients’ QOL. In general, the obtained results show that group meaning centered hope therapy in either patients’ group or families’ group led to improvement of patients’ QOL, which is consistent with the results of other studies on cancer patients’ QOL, including those of Yao, Spiegel, Snyder, Kang, Bijari, and Zamanian.[7,11,12,13,14,15]

With regard to the first hypothesis, “group meaning centered hope therapy is effective on patients’ QOL”, the test results showed that group meaning centered hope therapy in patients led to promotion of patients’ QOL. Group meaning centered hope therapy was conducted in none of the reviewed researches, but there were studies on other psychological interventions. In the study of Haravi, the effect of group counseling program on the QOL of 164 breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy was studied in two groups of study and control (n = 82, n = 82) and it was found that group counseling promoted patients’ QOL in all domains.[16] Also, Sharif et al.,[17] in a study on the effect of peer education on the QOL of breast cancer patients after surgery, showed an increase in patients’ QOL after the intervention.[17] Blake-Mortimer et al.,[18] in a literature review study on the promotion of quality and quantity of cancer patients’ life (a review on the efficacy of group psychotherapy), showed that group psychotherapy influenced not only the patients’ QOL but also their quantity of life (years of life) and led to more survival of these patients, reduction of their pain, reduction of their mood disorders, and improvement of their QOL. In addition, the results of a pilot study showed that an intervention like mindfulness-based stress reduction can result in an improvement of cancer patients’ physical and psychological status and QOL.[19] All the above-mentioned studies obtained results consistent with those of the present study, although they were not methodologically similar.

Test results of the second hypothesis revealed that group meaning centered hope therapy led to improvement of patients’ QOL. In the reviewed studies, group meaning centered hope therapy had been administered, but a meta-analysis was conducted by Northouse et al.[20] on the social–psychological care among the caregivers of cancer patients and they found that caregivers’ stress can result in sleep disorders and changes in their physical health and immunity system function. Psychological interventions presented in the research can relieve these signs in the caregivers of cancer patients and other chronic patients and improve their QOL. The authors of the latter article reported that these interventions can positively affect the patients’ signs and reduce their mortality, although they are practically less used. Their results are in line with the results of the present study, which showed that group meaning centered hope therapy in families is effective on patients’ QOL. In 2012, a study conducted on the effects of lung cancer complications on the patients and their caregivers showed that the patients, their caregivers, and their professional caregivers were all under the influence of cancer-related complications, faced QOL reduction, and needed supportive interventions.[21] The present study seems to have worked on a new issue (the effect of a combined intervention on QOL of the cancer patients and their families), as no similar study has been found on this by the researchers of the present study.

CONCLUSION

Cancer is one of the chronic diseases that affect the QOL of patients and their families. The obtained results showed that meaning centered hope therapy, if conducted either for the patients or for their families, can promote patients’ QOL. This finding is important in work therapy as in cases when the patient cannot attend group therapy sessions due to chemotherapy or other treatment problems, the patients’ QOL can be promoted by forming these sessions for the patients’ families, and the results should be specifically considered by nurses in their interaction with the patients and their families.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Islamic Azad University, Hamedan Branch

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frost MH, Johnson ME, Atherton PJ, Petersen WO, Dose AM, Kasner MJ, et al. Spiritual well-being and quality of life of women with ovarian cancer and their spouses. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sotodeh-Asl N, Neshat-Dust HT, Kalantari M, Talebi H, Khosravi AR. Comparison of effectiveness of two methods of hope therapy and drug therapy on the quality of life in the patients with essential hypertension. J Clin Psychol. 2010;2:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganz PA. Quality of life assessment in breast cancer: When does it add prognostic value for survival? Breast J. 2011;7:569–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snyder CR, Ritschel LA, Rand KL, Berg CJ. Balancing psychological assessments: Including strengths and hope in client reports. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:33–46. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rawnsley MM. Brief psychotherapy for persons with recurrent cancer: A holistic practice model. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1982;5:69–76. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altschuler A, Rosenbaum E, Gordon P, Canales S, Avins AL. Audio recordings of mindfulness-based stress reduction training to improve cancer patients’ mood and quality of life-a pilot feasibility study. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1291–7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao Y, Li H, Liu L, Zhao L, Xu L, Sun J. Study on the effect of feiji decoction for soothing the liver combined with psychotherapy on the quality of life for primary lung cancer patients. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2012;15:213–7. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2012.04.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valeberg BT, Grov EK. Symptoms in the cancer patient: Of importance for their caregivers’ quality of life and mental health? Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yousefy AR, Ghassemi GR, Sarrafzadegan N, Mallik S, Baghaei AM, Rabiei K. Psychometric Properties of the WHOQOL-BREF in an Iranian Adult Sample. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46:139–47. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosseinian E, Soodani M, Mehrabi Honarmand M. Efficacy of group logotherapy on cancer patients’ life expectation. J Behav Sci. 2010;3:287–92. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiegel D, Morrow GR, Classen C, Raubertas R, Stott PB, Mudaliar N, Riggs G. Group psychotherapy for recently diagnosed breast cancer patients: A multicenter feasibility study. Clinical TrialMulticenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. Psychooncology. 1999;8(6):482–493. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199911/12)8:6<482::aid-pon402>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snyder CR, Berg C, Woodward JT, Gum A, Rand KL, Wrobleski KK, Hackman A. Hope against the cold: Individual differences in trait hope and acute pain tolerance on the cold pressor task. J Pers. 2005;73(2):287–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00318.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang KA, Shim JS, Jeon DG, Koh MS. The effects of logotherapy on meaning in life and quality of life of late adolescents with terminal cancer. Controlled Clinical TrialResearch Support, Non-U.S Gov’t. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2009;39:759–768. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2009.39.6.759. doi: 10.4040/jkan. 2009.39.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bijari H, Ghanbari B, Aghamohammadi D. Effectiveness of group hope-therapy on Life expectency in Brest cancer patients. Foundation of Educations Research. 2009 Sep;10:172–185. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamanian S, Naziri G, Bolhari J. Effectiveness of Spiritual Group Therapy on Depression, Anxiety and Stress in Breast Cancer Patients. Quarterly Journal of Women and Society. 2012;3:85–116. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heravi M, Dehghan M. Efficacy of group psychotherapy on cancer patients’ quality of life. Daneshvar, 2006;13:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharif F, Abshorshori N, Hazrati M, Tahmasebi S, Zare N. Effect of peer-lead education on quality of life of mastectomy patients. J Iran Inst Health Sci Res. 2012;11:703–10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blake-Mortimer J, Gore-Felton C, Kimerling R, Turner-Cobb JM, Spiegel D. Improving the quality and quantity of life among patients with cancer: A review of the effectiveness of group psychotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1581–6. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lengacher CA, Kip KE, Barta M, Post-White J, Jacobsen PB, Groer M, et al. A pilot study evaluating the effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on psychological status, physical status, salivary cortisol, and interleukin-6 among advanced-stage cancer patients and their caregivers. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30:170–85. doi: 10.1177/0898010111435949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Northouse L, Williams A-l, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial Care for Family Caregivers of Patients with Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1227–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis J. The impact of lung cancer on patients and carers. Chron Respir Dis. 2012;9:39–47. doi: 10.1177/1479972311433577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]