Abstract

Background:

Dissatisfaction and tending to leave are some of the major nursing problems around the world. Professional commitment is a key factor in attracting and keeping the nurses in their profession. Commitment is a cultural dependent variable. Some organizational and socio-cultural factors are counted as the drivers of professional commitment. This study aimed to explore factors influencing the professional commitment in Iranian nurses.

Materials and Methods:

A qualitative content analysis was used to obtain rich data. We performed 21 in-depth face-to-face semi-structured interviews. The sampling was based on the maximum variation with the staff nurses and managers in 5 university affiliated hospitals. Constant comparative method used for data analysis

Results:

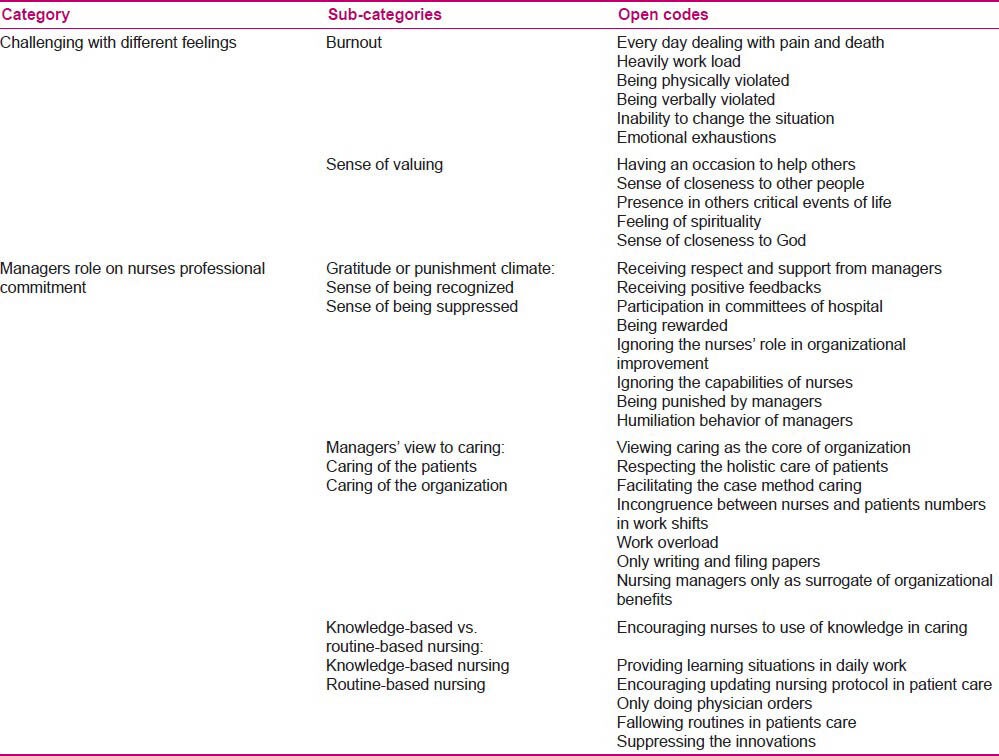

Two main categories were emerged: “Challenging with different feelings” and “Managers’ role”. Challenging with different feelings had two subcategories: “Burnout” and “sense of valuing”. The other theme was composed of three subcategories: “Gratitude or punishment climate”, “manager's view of caring” and “knowledge-based vs. routine-based nursing”.

Conclusions:

Findings revealed the burnout as a common sense in nurses. They also sensed being valued because of having a chance to help others. Impediments in the health care system such as work overload and having more concern in the benefits of organization rather than patient's care and wellbeing lead to a sense of humiliation and frustration. Congruence between the managers and nurses’ perceived values of the profession would be a main driver to the professional commitment. Making a sense of support and gratitude, valuing the care and promoting the knowledge-based practice were among the other important factors for making the professional commitment.

Keywords: Commitment, Iran, nurses, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

In the changing environment of health care, there are many concerns about attractiveness of the nursing profession. Questions like whether young people are attracted to this profession and whether the profession can retain the current working nurses are raised by researchers in this field.[1,2,3] Dissatisfaction and tending to leave are major worldwide problems in the nursing profession.[4,5,6,7,8] Feelings of stress, inadequacy, anxiety, and disempowerment in addition to working long hours are some of the reasons for leaving the profession.[9,10,11,12]

Similar to other countries, the nursing shortage and heavy workload of nurses are common issues in Iranian hospitals.[13] The impact of nursing shortage forces the nurses to work more than the required hours, with potentially 150 hours of overtime in some parts of the country.[14] Nurses describe nursing as a suffering experience.[15] Dissatisfaction, depersonalization and disappointment are common phenomena among nurses[16,17,18,19,20] and are responsible, for promoting the nurses to leave the profession.[18,21,22]

Nursing in the world strives for committed employees.[23] Professional commitment is in relation to the job profile and satisfaction in the society.[24,25] Commitment is one of the immediate antecedents of intention to leave the workplace; the higher nurses’ job commitment, the lower their intention to leave.[26] During the last two decades commitment has been a major focus of organizational behavior research.[27] It is assumed that committed employees engage themselves more in extra-role behaviors such as creativeness or innovativeness. They also have a higher degree of trust and intention to teamwork, which is essential for better performance of health care system.[28]

Becoming more educated and qualified, nurses perceive slighter dependence to organizations. Therefore, it is their commitment to the profession rather than organizations that could affect their behaviors.[29,30] McCabe and Garavan [2008] investigated the drivers of commitment amongst nurses using grounded theory method. The results were shown in three categories: (a) Shared values, vocational commitment, and patient care; (b) leadership, teamwork, and support; and (c) training, development and career progression. They emphasized on the importance of good leadership particularly that of line management.[31] Gould and Fontenla [2005], in a qualitative study found that being supported and having the opportunity to work in an interesting area are drivers of commitment.[24] Finding of a study about the professional commitment of public health nurses in Taiwan revealed that nursing administrators have an important role in enhancing the commitment of new nurses.[12]

Studies have shown that there is a relationship between commitment to the profession and affective and normative commitment to the organization.[30] According to Allen and Meyers’ model of commitment [1991], affective commitment refers to employees’ emotional attachment to the organization and its goals, and is identified with the effective involvement of employees in the organization. Normative commitment means a feeling of obligation to continue employment in the organization.[32] The important role of managers on development of affective or normative commitment among employees has been shown by several researchers.[33,34] In nursing studies social support from supervisors and trust the employers have been introduced as antecedents of organizational commitment.[3,35,36,37] Unit leadership, organizational culture and trust have also been found as predictors of nurses’ commitment.[2,38]

The context

Commitment is a cultural dependent concept.[29] Iranian nurses work in a traditional and religious culture. Nursing in Iran does not have an old history. It had not been recognized as a well-developed profession until 1916, when the first nursing school was established and nursing was introduced as an academic course.[39,40] Many years later, the nursing schools were established in the many of major cities. Currently about 8000 nurses are registered annually and 170,000 nurses are employed in the hospitals.[41] The nursing profession is governed by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education. There are 3 levels of nursing educational programs in Iran: Baccalaureate degree, Master degree (MSc), and PhD degrees. The majority of hospital nurses in Iran have the Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) and none of them are PhD.[39] Baccalaureate program is the only way to become a professional nurse.[19] Despite the fact that nursing educational program attempts to train the nurses in all branches of nursing such as public health, community health and geriatric, the majority of nurses are employed in private or university affiliated hospitals and very few are fitted in other roles.[14]

This study aimed to explore the factors that have an influence on professional commitment in nurses. Specifically, we aimed to address the following question “What are the factors that affecting the development of professional commitment in Iranian nurses?”

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is part of the first author's PhD dissertation in Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Tehran, Iran). The Ethical Committee of the University approved the protocol of the study.

A conventional content analysis approach was used. This method is used to analyze the interactions and can provide the insight into complex models of human thought.[42] The coding categories were derived directly and inductively from the raw data. This process includes: Open coding, categories creating and abstraction.[43] It is assumed that classifying the words into categories will share the same meaning.[44]

The study was conducted in five urban university hospitals. Three of them were general and two were specialized hospitals. Nurses in all the hospitals worked between 36-44 hours/week. Nurse/patient ratio in the critical care units and general wards were 1/3 and 1/12 respectively. Similar to the other Iranian hospitals, no nursing model was formally applied.

All the participants signed the written informed consent before interview. All of them were provided with relevant and adequate information about the purpose and scope of the study, the types of questions that would be asked and their freedom to leave the research at any time they wish. Finally, the permission for recording their voice was acquired. To keep the participant's information confidential, each contributor was given a pseudonym number (1-21) instead of their actual name.

Sampling was guided by predetermined criteria. All staff nurses, head nurses and nurse managers with a minimum of five years experience working in Iranian University hospitals, understanding and talking Persian, and willing to participate in the study considered as potential participants. 21 nurses working in 5 hospitals affiliated with 4 medical universities were selected through purposive sampling. The sampling was continued until data saturation (when no new categories or subcategories could be merged) was reached.

The data were gathered through a face-to-face, in-depth interview performed by the first author. All participants were interviewed separately in one or two sessions. Each session took about 45-120 minutes. The initial interview guide contained some general questions: “What do you think about the professional commitment?”, “Mention an occasion showing your outmost commitment to the nursing profession?”, “What are the influencing factors on your commitment to nursing?” and “Please describe an actual experience as a nurse that will help me understand what professional commitment means to you”. These general questions sharpened the interview guide by adding some new questions “Describe a situation that you think the manager's decision influences your commitment” and “How could managers’ view of nursing influences your commitment?” The interviews were carried out in the nurses’ room either after or before the working period.

After each interview, the researcher made field notes on the emotional tone of the interview and difficulties that encountered during the interview. Memo writing also was done to document the analytic ideas in relation to the data.

The interviews were recorded by a digital voice recorder and were transcribed later. The interview process was continued over a ten-month period. Data saturation, the point that no more new information could be emerged, was achieved with 21 participants.

In this study four trustworthiness criteria of credibility, conformability, transferability and dependability, as proposed by Lincoln and Guba, were used.[45]

The credibility of the study was supported by prolonged engagement with the participants, maximum variant sampling and member checking. Participants were selected from various hospitals with different size and service. Moreover, they were chosen from different age categories with different work experiences, educational degrees, and organizational grades.

After data analysis a copy of the interview transcript was given to the participants, however, none of the participants made any changes or comments on their manuscript.

To enhance the dependability and conformability of data, a team-based approach for data analysis was used. The interview transcripts were coded by this team and the emerged categories were discussed and agreed. Also, two other qualitative researchers were asked to randomly review the interviews and code the transcripts. There was a close agreement regarding the resultant coding between these two researchers and the research team.

Thick description of the sample and setting of study may help readers make decisions about the transferability of findings. The results were also discussed with the nurses from other settings, and they confirmed the fitness and transferability of the results to other settings.

The transcribed interviews, field notes, and memos were initially studied to obtain a comprehensive view of data. The texts were then read line by line and the passages were separated into sections with similar content. The texts were divided into smaller more feasible units and meaningful statements and paragraphs were identified and underlined as the units of analysis. Each meaningful statement was given a freely generated code. The coded and original files were reviewed by the researchers for truthfulness, and the participants were asked to review them for more precision. Codes with similar meaning were grouped together. The various codes were compared on the basis of similarities and differences. Then they were accordingly grouped into categories.

The transcripts were evaluated again to validate the codes and categories. For purpose of abstraction, the relationships between categories were identified and major themes emerged.

RESULTS

The participants of this study were 17 women and 4 men with the mean age of 38.86 years, and the mean work history of 14.38 years. About 82% (n = 14) of the participants were hospital unit's in charge, 3 were ward staff and 4 were nurse administrator of different hospitals.

The results of the study revealed that challenging with different feelings and role of the nurse manager are the most important factors in development of professional commitment. Other factors were organizational structure and culture, financial security and social factors.

In this paper we will discuss “challenging with different feelings” and “role of nurse managers” as the main emerged categories from the content analysis. Categories, subcategories and open codes are represented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Converging points supporting the two main categouries

Challenging with different feelings

The participants had different experiences in nursing, which made them more committed or hinder them from commitment to the profession. We classified these experiences into two categories: “Burnout” and “sense of valuing”.

Burnout

Most of the participants named factors such as everyday dealing with pain, suffering and death, heavy workload, and being violated as the factors that produce a continuous stress for them. One of the participants said: “As a nurse, you always deal with the patients’ pain, suffering, cries and death; it would be a bad pain”.

Dealing with transmittable diseases was also of concern: “There are lots of unknown diseases and infectious diseases. I have two kids; I am always in fear to spread disease to my home”.

The nurses also believed that nursing shortage in work shift, disproportionate nurse-patient ratio and work overload hinder them from commitment. For example, one participant said: “We have to hurry all the moments and we have a lot of work left all the time; I think how I can escape this situation”.

They mentioned that this working situation makes nurses more exhausted: “Exhaustion is an inseparable criterion for nurses, physical or mental. You could see the tiredness and exhaustion in our faces”. They believed that such feeling weaken their initial motivation and is a cause of frustration or withdrawing from the profession: “I think I lost my initial motivations…. All nurses wish to change their jobs to a more convenient situation.”

Such a feeling makes them feel isolated or forces them to try to leave the profession. They make only the minimum of their tasks without any sense of responsibility or belonging: It's no choice, I do only my own tasks to full the job hours”.

Experiencing violence was another cause of burnout. They named verbal and physical violence as mediators of dissatisfaction and turnover in nurses: “All of nurses have experienced verbal violence from patients, their families or even physicians”. One of the participants said: “We were suturing a patient in the outpatient operating room when some men entered and violated all the staff with knives…I can never forget that situation; I think it crashed my soul.” Work overload and stress sometimes had terrible consequences: “Both work overload and stress in this job were the main causes of my fetus death. I think that I am experiencing depression. How I could be committed to this profession.”

Sense of valuing

Some of the participants mentioned that nursing is a high valued profession. They feel an inherent spirituality in nursing. “Being called to this profession” was mentioned by some of the participants: “I felt I have called to help others, it was a gold time for me to make my best decision in my life”. They believed that being close to others’ suffering led them to have another view of life: “After 29 years of working as a nurse, I feel the presence and support of God in pain, in relief, in death or in life. It's a very pleased feeling.”

Some of them viewed nursing as a chance of helping others and remembering this made them more committed: “I think that it's the best way to help others so I am committed to this profession”.

Role of nurse managers

The role of managers was composed of three categories: “Gratitude or punishment climate”, “managers’ view of caring”, and “knowledge-based vs. routine-based nursing”.

Gratitude or punishment climate

The participants believed that providing a sense of respect and gratitude is a major antecedent of commitment. Relationship-based valuing and respecting could have association with increased commitment in nurses. This category had two dimensions: “The sense of being recognized” and “the sense of being suppressed”.

The sense of being recognized

The participants named factors such as being supported, respected and recognized as facilitators for the development of professional commitment:

“They named me as a competent nurse and selected me to be awarded. You see, after that, I thought I had to be more committed; it was a good feedback for me”.

The participants also believed that perceived value of their managers makes them more committed to the nursing. One of the head nurses said: “I try to gratitude them, because it makes them more committed”. And a nurse said: “We have a close relationship with our head nurse, she is very kind and supportive so we tried to do our best and we feel a sense of belonging”.

The sense of being suppressed

Experience of being suppressed was mentioned by participants: “They (managers) left no chance for me to show my ability, my knowledge. They suppress my confidence”. And another nurse who accomplished her bachelor science degree said: “They (managers) try to suppress me because they think I can occupy their positions”. This approach has led nurses to frustration, disaffection and finally leaving the profession: “How I can be committed when I feel that they do not understand my work's value?” Such a feeling forced some of the participants to attempt to leave the profession or made them isolated. They make only the minimum of their tasks without any sense of responsibility or belonging: “Sometimes, I think why I am working here? Whom am I doing these services for? I don’t care about anything. I do only my tasks”.

Managers’ view of caring

The nurses sensed a conflict between their view and that of managers on patient care. This category had two dimensions: “Caring for the patients” and “caring for the organization”.

Caring for the patients

Nurses described the caring as the essence of this profession. They believed that caring for the patients is an occasion that forces them to be more committed. The participants believed that loving other people as well as being concerned about the patient's needs is the most important reason for commitment to the nursing profession: “I am committed to help poor patients. You know, I never think of leaving this job”. Providing a holistic care made them more committed to the nursing: “When you have a holistic care, you have a good sense”. “Nursing is making a holistic care”.

Caring for the organization

Some nurses believed that nurse managers only focus on organizational benefits: “It seems that they don’t think about caring; they only think of forms and papers”. Work overload and ignoring the nursing's principles make them less committed to the nursing: “I think that it doesn’t satisfy me; I had another purpose when I chose nursing. They (managers) have forgotten the essence of nursing”. They sensed a role conflict.

Knowledge-based vs. routine- based nursing

The participants believed that focus on knowledge-based practice is an important antecedent of commitment:“Everyone likes to work in a professional and valuable situation. When we work in a scientific manner, based on the nursing knowledge and researches we would sense more valuing and it make us more committed”. They mentioned that managers’ focus on knowledge-based nursing makes a sense of valuing: “I am working in a ward that they gratitude my knowledge it's so valuable”.

Some of the participants mentioned that the nursing managers only focus on routine tasks and have no attention to knowledge-based practice. They believed that this view of nursing practice makes nurses more disappointed and withdraw them from commitment: “We studied for at least 4 years to become a nurse, but they [managers] expect us to do only routine jobs”. They also believed that routine-based practice has a negative impact on the society's perception of nursing: “People consider nursing as a low-level job. They think that we are physicians’ aid; this is the main reason I want to leave this profession”.

The participants mentioned that providing occasion for learning and education in hospitals could create more satisfaction and commitment in the nurses. A nursing administrator said: “Providing more educational plans, we try to emphasize on the nurses’ role in the hospital. We think this trend makes them more committed”.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study supported the findings of other researchers who concluded that commitment is in relation with shared values, teamwork and professional progression.[31] Our findings also indicated that the professional commitment is formed by varied experiences in nursing. Nursing is considered to be inherently stressful and burnout of the nurses was reported by previous researchers as a common outcome of the nursing profession.[9,46] Staff crisis in hospitals, heavy workload, lack of support and poor income, lead nurses to burnout.[13,9,47] Researchers have shown the negative impact of workload and stress on work attitude and performance.[48] This condition forms a breeding ground for dissatisfaction and poor professional commitment.

Our findings are also in relation with other researches who emphasized on valuing of empathy and altruistic behavior by nurses.[48] Most of the nurses enter this profession only for the sake of altruism and helping others.[49] Although calling to a profession and altruism in isolation cannot be very efficient in the modern nursing profession, but sharing the values between nurses and profession have a key role in building the commitment. Valuing the nursing is also in accordance with traditional and religious culture of Iran. It has been shown that Iranian nurses assume their professional commitment as a result of their religious beliefs that value helping others.[50,51]

In this study, both nurse manager's support and efficient feedback were among the strategies suggested by the participants to facilitate the professional commitment. This finding is supported by other researches as well. Offering a positive feedback leads to generation of a grateful culture.[52] McCabe and Garavan [2008] indicated that strong and supportive leadership could positively influence the commitment of nursing staff.[31] In a study of Iranian nurses turnover, the majority of turned over nurses mentioned the lack of support and feeling of diminishing in nursing profession.[53] Researchers have shown that communication-based confidence, mutual respect and support could have positive impact on personal commitment.[33] Meta-analysis of antecedents of commitment revealed that by providing a supportive work environment, managers can foster affective commitment in their staff.[27] The results of this study showed that viewing the nursing as a caring profession is one of the major antecedents of commitment in nurses. Managers who emphasize on the caring role of the nurses could act as the facilitators in making commitment. This finding is supported by other researches. Support for a nursing (vs. medical) model of patient care is introduced in nurses’ work- life model. There is a negative relationship between a nursing model of care and emotional exhaustion.[47] Nurses emphasize on caring as the core of nursing and mention it as a reason for their commitment.[31] Researchers conceptualized the professional commitment as acceptance of professional values and goals.[30] Congruence between managers and nurses perceived value of the profession would be a main driver of the nurse commitment.

Our findings showed that managers’ focus on knowledge-based caring and emphasizing on improvement of professional knowledge could be effective in the development of professional commitment sense in nurses. If nurses sense a conflict between their professional knowledge and organizational expectations, they will lose their commitment.[46] When the capabilities of nurses in providing knowledge-based care are ignored by the managers, dissatisfactions and intention to leave could be created.[54] In a causal model of organizational commitment there was a negative relation between routine-based practice and commitment. Routine-based practice would hinder nurses from commitment.[35] It could also be concluded that if the managers only focus on routines and physician orders, nurses would have no sense of commitment to their profession.

CONCLUSIONS

The study found the burnout as a main constraint of the nursing professional commitment. Staff crisis in hospitals and work overload are some of the main causes of burnout. Experiencing violence and dealing with others pain and disease make continuous stress in nurses and hinder them from the commitment. Burnout has been reported as a worldwide problem in nursing. Rescheduling the work shifts and redesigning the nursing workplace as well as providing more physical, emotional, and legal support, are some of the suggestions to reduce the exhausted feeling. The managers have an important role in developing the professional commitment. Making a sense of gratitude and respect in nurses by offering them opportunities in making decisions on their own affairs is important. In order to have a good and effective feedback, the managers and head nurses should be in close connection with the nurses at all levels to realize their capabilities and efforts. As nurses are committed to offer the best nursing care to the society, there is a need for scientific and research-based practice to show their special knowledge and skills. Supporting the ongoing professional training and development could positively influence the commitment.

The overall findings of this study suggest that nursing in Iran needs a specific care, and the nurse managers have an important role to link and hold the nurses within their profession.

Study limitations

The findings of this study are limited to the nursing staff working in 5 hospitals in Iran. Transferability of the findings depends upon whether readers recognize the results in the nursing profession. Although it is a qualitative study in Iranian nurses, but as stated in the literature nursing in the world has common concerns. Consistent with qualitative methodology, readers are the final authorities on how well the findings resonate with practice based on their own meaning and context.

Contextual features of the participants and setting of this study have been provided to help readers make decisions about the transferability of the findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank all participants for their courage, willingness, and time to participate in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Tehran University of Medical Scienses, Tehran, Iran

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuokkanen L, Leino-Kilpi H, Katajisto J. Nurse empowerment, job-related satisfaction, and organizational commitment. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003;18:209–15. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregory DM, Way CY, LeFort S, Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS. Predictors of registered nurses’ organizational commitment and intent to stay. Health Care Manag Rev. 2007;32:119–27. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000267788.79190.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loi R, Hang-Yue N, Foley S. Linking employees’ justice perceptions to organizational commitment and intention to leave: The mediating role of perceived organizational support. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2006;79:101–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tallman R, Bruning NS. Hospital nurses' intentions to remain: Exploring a northern context. Health Care Manag. 2005;24:32–43. doi: 10.1097/00126450-200501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coomber B, Barriball KL. Impact of job satisfaction components on intent to leave and turnover for hospital-based nurses: A review of the research literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;44:297–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gershon RR, Stone PW, Zeltser M, Fausett J, Macdavitt K, Chou SS. Organizational climate and nurse health outcomes in the United States: A systematic review. Ind Health. 2007;45:622–36. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westendorf JJ. The nursing shortage: Recruitment and retention of current and future nurses. Plas Surg Nurs. 2007;27:93–7. doi: 10.1097/01.PSN.0000278239.10835.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.English B, Chalon C. Strengthening affective organizational commitment the influence of fairness perceptions of management practices and underlying employee cynicism. Health Care Manag. 2011;30:29–35. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0b013e3182078ae2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. A model of burnout and life satisfaction amongst nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2007;32:454–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers AE, Hwang WT, Scott LD, Aiken LH, Dinges DF. The working hours of hospital staff nurses and patient safety. Health Aff. 2004;23:202–12. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bally JM. The role of nursing leadership in creating a mentoring culture in acute care environments. Nurs Econ. 2007;25:143–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu KY, Chang LC, Wu HL. Relationships between professional commitment, job satisfaction, and work stress in public health nurses in Taiwan. J Prof Nurs. 2007;23:110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rafii F, Hajinezhad ME, Haghani H. Nurse caring in Iran and its relationship with patient satisfaction. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2008;26:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajbaghery MA, Salsali M. A model for empowerment of nursing in Iran. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:24–3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nasrabadi AN, Emami A, Yekta ZP. Nursing experience in Iran. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9:78–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1322-7114.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirzabeigi G, Sanjari M, Heidari S. Job satisfaction among Iranian nurses. Hayat. 2009;15:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khazaei I, Khazaee T, Sharifzadeh GH. Nurses professional burnout and some predispoing factors. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2006;13:56–69. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joolaie S, Mehrdad M, Bohrani N. Nursing students opinions about nursing profession and turnover. Iran J Nurs Res. 2006;1:21–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farsi F, Dehghan-Nayeri N, Negarandeh R. Nursing profession in Iran: An overview of opportunities and challenges. Japon J Nurs Sci. 2010;7:9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2010.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roohi GH, Asayesh H, Rahmani H, Abbasi A. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment in nurses in Golestan Medical University haspitals. Payesh. 2011;10:285–92. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahangir F, Shokrpour N. Three components of organizational commitment and job satisfaction of hospital nurses in Iran. Health Care Manag. 2009;28:375–80. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0b013e3181b3eade. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hajbagheri MA, Dianati M. Personality fitness of nursing students to study and work in nursing profession. Iran J Med Educ. 2005;4:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chitty KK. The professionalization of nursing. In: Chitty KK, Black BP, editors. Professional nursing: Concepts and challenges. St. Louis: W.B. Saunders; 2007. pp. 163–95. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould D, Fontenla M. Commitment to nursing: Results of a qualitative interview study. J Nnurs Manag. 2006;14:213–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LLapa-Rodríguez EO, Trevizan MA, Shinyashiki GT. Conceptual reflections about organizational and professional commitment in the health sector. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2006;16:484–8. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692008000300024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teng CI, Lotus Shyu YI, Chang HY. Moderating effects of professional commitment on hospital nurses in Taiwan. J Prof Nurs. 2007;23:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer JP, Stanley DJ, Herscovitch L, Topolnytsky L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J Vocat Behav. 2002;61:20–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khatri N, Halbesleben JR, Petroski GF, Meyer W. Relationship between management philosophy and clinical outcomes. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32:128–39. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000267789.17309.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen A. Agenda: Univ., Inst. Technik und Bildung; 2007. Dynamics between occupational and organizational commitment in the context of flexible labor markets: A Review of the Literature and Suggestions for a Future Research; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahman NM, Hanafiah MH. Commitment to organization versus commitment to profession: Conflict or compatibility? J Pengurusan. 2002;21:77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCabe TJ, Garavan TN. A study of the drivers of commitment amongst nurses: The salience of training, development and career issues. J Eur Ind Train. 2008;32:528–68. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen NJ, Meyer JP. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J Occup Psychol. 1990;63:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manion J. Strengthening organizational commitment: Understanding the concept as a basis for creating effective workforce retention strategies. Health Care Manag. 2004;23:167–76. doi: 10.1097/00126450-200404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhoades L, Eisenberger R, Armeli S. Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:825–36. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Currivan DB. The causal order of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in models of employee turnover. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2000;9:495–524. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spence Laschinger HK. Effect of empowerment on professional practice environments, work satisfaction, and patient care quality: Further testing the nursing worklife model. J Nurs Care Qual. 2008;23:322–30. doi: 10.1097/01.NCQ.0000318028.67910.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Way C, Gregory D, Davis J, Baker N, LeFort S, Barrett B, et al. The impact of organizational culture on clinical managers’ organizational commitment and turnover intentions. J Nurs Adm. 2007;37:235–42. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000269741.32513.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spence Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Wilk P. Context matters: The impact of unit leadership and empowerment on nurses’ organizational commitment. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39:228–35. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181a23d2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabari Khomeiran R, Deans C. Nursing education in Iran: Past, present, and future. Nurs Educ Today. 2007;27:708–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nikbakht Nasrabadi A, Emami A. Perceptions of nursing practice in Iran. Nurs Outlook. 2006;54:320–7. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ino.ir. Iraian Nursing Organization. [Last updated on 2011 May 16; cited on 2011 May 16]. Available from: http://www.ino.ir .

- 42.Dehghan-Nayeri N, Nazari AA, Salsali M, Ahmadi F. Iranin staff nurses’ view of their productivity andhuman resourse factors improving and impeding it: A qualitative study. Hum Resour Health. 2005;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polit DF, Beck CT, Hungler BF. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2008. Essentials of nursing research: Methods, appraisals and utilization; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu H, While AE, Barriball KL. Job satisfaction and its related factors: A questionnaire survey of hospital nurses in Mainland China. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44:574–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spence Lashinger HK, Leiter MP. The impact of nursing work environments on pateient safty outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2006;36:259–67. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200605000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horton K, Tschudin V, Forget A. The value of nursing: A literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14:716–40. doi: 10.1177/0969733007082112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNeese-Smith DK, Crook M. Nursing values and a changing nurse workforce: Values, age and job stages. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33:260–70. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahimaghaee F, Dehghan-Naiery N, Mohammadi E. Iranian nurses perception of their professional growth and development. Online J Issues Nurs. 2010;16:10. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01PPT01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jafaraghaee F, Parvizy S, Mehrdad N, Rafii F. Concept analysis of professional commitment in Iranian nurses. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17:472–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gess E, Manojlovich M, Warner S. An evidence-based protocol for nurse retention. J Nurs Adm. 2008;38:441–7. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000338152.17977.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hooshmand-Behabadi A, Sayf H, Nikbakht-Nasrabadi A. Survey of nurses burnout in a 10 years period. Teb va Tazkie. 2001;10:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watson J. Caring science and human caring theory: Transforming personal and professional practices of nursing and health care. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2009;38:466–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]