Abstract

The pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties of the azalide azithromycin distinguish it from other antibiotics. The PK profile of azithromycin features high tissue-to-serum ratios, including high concentrations in the middle ear, and a prolonged elimination half-life. These characteristics result from the accumulation of drug within cells and its subsequent slow, sustained release from cells and tissues into the bloodstream. The PD properties of azithromycin include bactericidal activity against key respiratory tract pathogens and a prolonged postantibiotic, or persistent, effect. In addition, white blood cells deliver the drug to infected foci, thereby enhancing local tissue concentrations and improving in vivo efficacy. Recent PK studies in mice suggest that a single, large dose of azithromycin achieves higher tissue concentrations than do multidose regimens. Other studies in animal infection models, in particular, a gerbil model of acute otitis media, have demonstrated improved bacterial eradication when azithromycin is administered as a single dose rather than divided over 2 or 3 days. Taken together, the results from these preclinical studies provide a PK/PD rationale for the use of single-dose azithromycin in the treatment of acute otitis media. Clinical data on the efficacy and safety of single-dose azithromycin for the treatment of acute otitis media in children are presented in 2 accompanying articles in this supplement.

Keywords: azithromycin, acute otitis media, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics

Introduction

Azithromycin oral suspension was introduced in 1995 in the United States as a novel, 5-day treatment for acute otitis media (AOM) in children. More recently, 3-day and single-dose regimens for AOM have become available.1 The successful development of short-course and especially single-dose antibiotic regimens is governed by the pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties of the agent. PK refers to the absorption, distribution, and elimination of a drug, whereas PD refers to the relationship between drug concentration and the pharmacologic and toxicologic effects of the agent. For antibiotics, the relationship between concentration and antimicrobial effect is of key interest. The interrelationship between PK and PD determines the dosing duration and total dose required for optimal efficacy.2 This article presents a review of the PK and PD characteristics of azithromycin that support its use as single-dose therapy for AOM in children.

Pharmacokinetics of azithromycin

Entry of azithromycin into cells

Azithromycin is the sole member of the azalide subclass of macrolide antibiotics. Derived from erythromycin, it differs chemically in that a methyl-substituted nitrogen atom is incorporated into the lactone ring (Figure 1). The incorporation of a second, ionizable amine group has resulted in key improvements over erythromycin: in particular, greater tissue penetration and an extended half-life of >60 hours.3 The net charge of the azithromycin molecule varies depending on the pH of the environment. A weak base at physiologic pH, azithromycin is essentially nonpolar and lipophilic, and able to penetrate cell membranes. Within the cytosol, where the pH is about 0.5 units lower than the extracellular pH, the drug is protonated and accumulates intracellularly. The low pH within lysosomes favors ionization to the dicationic form, thereby tending to slow diffusion out of the cell.4 Carlier et al5 reported that cell-associated azithromycin distributes mostly in the lysosomal compartment; however, 30% to 50% of drug is freely soluble in cytosol.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the chemical structures of azithromycin and erythromycin.

The ability of azithromycin to accumulate intracellularly has been demonstrated in fibroblasts,4 epithelial cells,6,7 and macrophages,8 cell types found in all tissues and organs. In addition, azithromycin concentrates within neutrophils and monocytes.8,9 Whether this intracellular accumulation involves an active, saturable transport process has been studied in in vitro cell culture systems. In human fibroblasts and mouse macrophages, the entry of drug into the cell is rapid, and the intracellular concentration is proportional to both time of incubation and extracellular concentration (Figure 2).4,8 This linear relationship suggests a nonsaturable process. Inhibitors of glycolysis and oxidative metabolism do not affect the entry process, nor is it affected by inhibitors of known membrane-transport systems for nucleosides, hexoses, or amino acids.4,10 Thus, entry does not appear to involve energy-dependent active transport. Instead, the direct relationship between extracellular concentration and intracellular accumulation is consistent with a process of simple diffusion. In addition, the inhibition of entry by lowering incubation temperature or formalin fixation of cells suggests that membrane fluidity is important and further supports a diffusion mechanism.4

Figure 2.

Intracellular versus extracellular accumulation of azithromycin and erythromycin within human fibroblasts.4

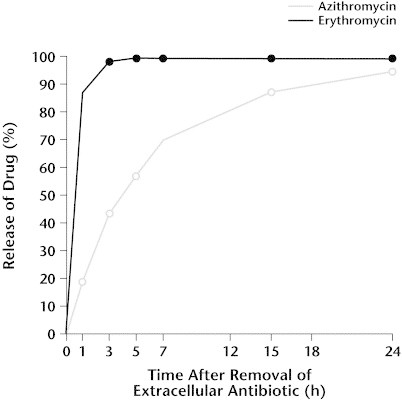

Release of azithromycin from cells

In studies using human fibroblasts, Gladue and Snider4 reported that the intracellular accumulation of azithromycin after 72 hours of incubation was more than 20 times higher than that of erythromycin (61.2 vs 2.9 μg/mg of protein). Subsequent incubation of azithromycin- and erythromycin-loaded cells in drug-free medium resulted in a slower and more sustained rate of diffusion out of the cells for azithromycin than for erythromycin. This is likely due to the presence of 2 ionizable amine groups in azithromycin as compared with 1 for erythromycin, resulting in slower release from the cell's lysosomal compartment.5 However, by 48 hours, >70% of intracellular azithromycin was released into the medium. In addition, although azithromycin was released slowly, the absolute amount of drug released over time was high because of the high initial drug concentrations within the cells.4 Release of azithromycin by mouse macrophages was also shown to be slower than that of erythromycin. However, after 24 hours of incubation in drug-free medium, >90% of intracellular drug was released into the medium (Figure 3).8 More recently, studies using rat embryo fibroblasts and epithelial-like rat kidney cells have confirmed these results.5 Thus, the opposing forces of intracellular accumulation and extracellular release create a dynamic equilibrium, resulting in the high, sustained tissue concentrations and long half-life characteristic of azithromycin.

Figure 3.

Release of azithromycin and erythromycin from mouse peritoneal macrophages. Reproduced with permission.8

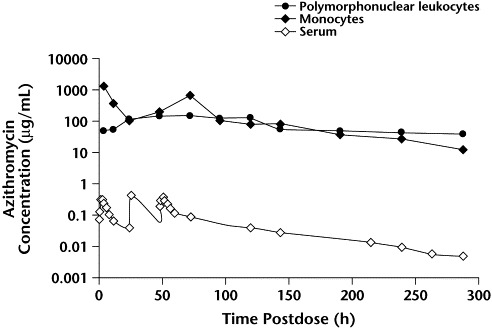

White blood cells serve as a targeted drug delivery system

In contrast to low levels in serum, azithromycin concentrations within neutrophils and monocytes range from 100 μg/mL to 1000 μg/mL and remain high for several days after dosing (Pfizer Inc, data on file; Figure 4). Despite these high intracellular concentrations, in vitro studies have shown that azithromycin-loaded neutrophils and tissue macrophages are capable of generating an oxidative burst on stimulation with either phorbol myristate acetate or Staphylococcus aureus,8 and of migrating in response to a chemotactic stimulus.11 Incubation of macrophages with opsonized S aureus leads to phagocytosis of the organism and release of 80% of intracellular drug, in biologically active form.8

Figure 4.

Serum and leukocyte concentrations of azithromycin following oral administration of a single 500-mg dose to 12 healthy adults (Pfizer Inc, data on file).

This in vitro evidence that circulating white blood cells can not only concentrate azithromycin but also migrate to the infection site and release bioactive drug has been confirmed in vivo. Using a mouse model of S aureus soft-tissue infection, Retsema and colleagues12 compared S aureus-infected thighs with contralateral saline-injected thighs at various times after infection. Animals were treated with azithromycin immediately after infection. Microscopic examination of tissues 24 hours after infection demonstrated extensive muscle necrosis and massive inflammatory infiltrates in infected thighs. By 24 to 72 hours after administration of drug, the concentration of azithromycin in infected thighs was significantly higher than that in uninfected, saline-injected thighs. Furthermore, the azithromycin was biologically active, as confirmed using a standard bioassay. Thus, circulating white blood cells serve as a targeted drug-delivery system by concentrating azithromycin intracellularly, migrating to the infection site, phagocytosing the pathogen, and releasing active drug, thereby increasing local azithromycin concentrations.

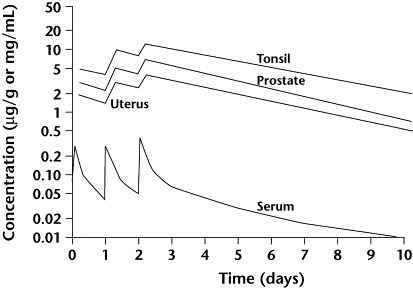

Pharmacokinetic support for short-course azithromycin therapy

The intracellular accumulation and slow release of azithromycin are key determinants of the unique PK profile of the drug. Concentration-versus-time curves feature high, sustained drug concentrations in tissues and comparatively low concentrations in serum (Figure 5).13 The prolonged elimination half-life (>60 hours) allows for once-daily dosing.3

Figure 5.

Tissue and serum pharmacokinetics of azithromycin 500 mg administered once daily for 3 days. Reproduced with permission.13

In a study of children with AOM, azithromycin 10 mg/kg administered on day 1 followed by 5 mg/kg on day 2 achieved mean peak middle-ear fluid concentrations of 8.6 and 9.4 μg/mL at 24 and 48 hours after the initial dose, respectively.14 In contrast, at 48 hours after treatment, azithromycin concentrations in plasma were ∼300 times lower than those in middle-ear fluid.

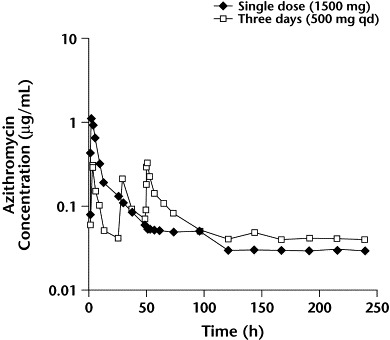

The PK of azithromycin after administration of a single oral dose was recently analyzed by Amsden and Gray.15 The authors administered a 1500-mg dose to adult volunteers either as a single, large dose or divided over 3 days (500 mg/day). Serum concentration-vs-time curves for the 2 regimens are shown in Figure 6. Serum exposures (area under the concentration-vs-time curve; AUC) for the 2 regimens were not significantly different (13.1 vs 11.2 mg·h/L, respectively). As expected, the peak serum concentration (Cmax) after a single dose was significantly higher than that for the 3-day regimen (1.46 vs 0.54 mg/L, respectively; P = 0.001). Previous studies have shown a correlation between the serum and tissue PK of azithromycin.13 Thus, a single, large dose may be preferable to multiple divided doses for achieving optimal tissue concentrations.

Figure 6.

Mean azithromycin serum concentrations vs time after a 1500-mg dose, administered as either a single dose or divided over 3 days (500 mg QD). Reproduced with permission.15

Pharmacodynamics of azithromycin

Although macrolides generally have been regarded as bacteriostatic, several in vitro and in vivo studies have confirmed that azithromycin is bactericidal against key pathogens. In vitro time–kill experiments comparing the activity of azithromycin, erythromycin, and roxithromycin against 70 strains of Haemophilus influenzae showed that the bactericidal effect of azithromycin was significantly more rapid and extensive than that of the other 2 agents.16 Both cidality and bacterial eradication by azithromycin have been demonstrated in a number of animal models, including pneumococcal pneumonia and localized Streptococcus pyogenes infection in mice, viridans streptococcal endocarditis in rats, and pneumococcal otitis in gerbils.17

In the pneumococcal otitis and pneumonia models cited above, higher doses of azithromycin achieved enhanced bacterial killing.17 Similarly, a study by Babl et al18 demonstrated a dose-dependent bactericidal effect in a chinchilla model of H influenzae AOM. In that study, the rate and extent of reduction in bacterial load after a high-dose azithromycin regimen were significantly greater than those seen after a 4-fold lower dose. In addition, the higher dose achieved complete sterilization of the ear in a significantly higher proportion of animals than did the lower dose. A clinical correlate of this dose-dependent antibacterial effect was recently reported by Cohen et al19 in a study of group A streptococcal pharyngitis in children. The authors compared the efficacy of two 3-day azithromycin regimens, 10 and 20 mg/kg daily, and demonstrated significantly higher bacteriologic eradication rates among children who had received the 20 mg/kg daily regimen.

Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic predictors of efficacy

Antibacterial agents have been classified as either concentration dependent or time dependent, based on their pattern of bactericidal activity.2 Members of the first group, which includes aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones, display concentration-dependent killing over a wide range of concentrations. As drug concentration increases, the rate and extent of killing also increase. For these agents, the PK/PD predictor of efficacy is AUC/MIC or Cmax/MIC (where MIC is the minimal inhibitory concentration), and the goal of dosing is to maximize drug concentration. Agents in the second group, which includes penicillins and cephalosporins, display minimal concentration-dependent killing. Although enhanced killing may be seen as the concentration is increased from 1 to 4 times the MIC, no further enhancement is seen at higher concentrations. The extent of bacterial killing for this group is largely dependent on the length of exposure. For time-dependent agents, maintaining drug concentrations above the MIC for at least 40% of the dosing interval is the best predictor of efficacy, and the goal of dosing is to optimize the duration of exposure.2

Classification of macrolide and azalide antibiotics has been somewhat less clear-cut.20 For erythromycin and clarithromycin, time above MIC was previously thought to correlate best with efficacy.20,21 However, a recent report suggested that AUC/MIC is a better predictor of efficacy for these macrolides.22 For azithromycin, although dose-dependent bacterial killing has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo,16–19 the drug's pattern of bactericidal activity has been classified as time dependent, like that of the beta-lactams.21 However, unlike the beta-lactams, the PK/PD efficacy parameter for azithromycin is AUC/MIC (Table).20–22 This is due to the drug's prolonged in vivo postantibiotic, or persistent, effect. The persistent effect refers to the continued suppression of bacterial growth following exposure to, and subsequent removal of, an antimicrobial.2 Thus, as shown by Craig23 using a mouse thigh infection model, increasing the azithromycin dosing interval from 6 to 12 or 24 hours had minimal impact on bacteriologic efficacy. The author also noted that the cumulative dose of azithromycin required for efficacy in neutropenic mice was about 4 times less than that in normal mice, highlighting the contribution of circulating white blood cells. Hence, because of sustained concentrations in tissues and white blood cells, and an extended persistent effect, total dose rather than dosing regimen is the major determinant of in vivo efficacy for azithromycin.23

Table.

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) predictors of bacteriologic efficacy.20–22

| Antimicrobial Class | Pattern of Bacterial Killing | PK/PD Predictor of Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones | Concentration dependent | AUC/MIC or Cmax/MIC |

| Beta-lactams | Time dependent | Time above MIC |

| Macrolides, azalides | Time dependent | AUC/MIC |

AUC = area under serum concentration-vs-time curve; Cmax = peak serum concentration; MIC = minimal inhibitory concentration.

Experimental support for single-dose azithromycin in AOM

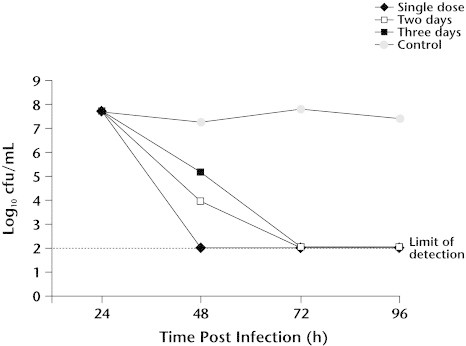

Recent studies by Girard and associates24 have demonstrated that azithromycin performs best when administered as a single dose rather than once daily for 2 or 3 days. These studies included mouse models of pneumococcal pneumonia, peritonitis due to Enterococcus faecalis or S pyogenes, and a gerbil model of H influenzae otitis. In the mouse models, a single, large dose of azithromycin achieved significantly higher survival rates than did the same dose divided over 2 or 3 days. In the gerbil otitis model, all 3 regimens sterilized the middle ear; however, the single-dose regimen demonstrated significantly more rapid bacterial killing and earlier sterilization of the middle ear (Figure 7). In companion studies, Girard et al24 also analyzed azithromycin PK in the mouse. The authors showed that the total exposure (AUC) in serum and lung was independent of the dosing regimen, whereas peak concentrations were highest with the single-dose regimen. These findings are consistent with those reported by Amsden and Gray15 in their PK analysis of 1-day versus 3-day azithromycin therapy in adult volunteers.

Figure 7.

Bactericidal activity of single versus multidose regimens of azithromycin 200 mg/kg in a gerbil model of Haemophilus influenzae acute otitis media. Reproduced with permission.24

Conclusions

The PK properties of azithromycin feature an extended half-life and sustained tissue concentrations, allowing for once-daily dosing and shorter-course therapy. The PD characteristics of azithromycin—a prolonged and persistent effect, bactericidal activity against key pathogens, and an enhanced antimicrobial effect resulting from accumulation within white blood cells—suggest that a single-dose regimen would be as effective as the same dose divided over several days. Finally, an apparent efficacy advantage of single versus multidose regimens has been demonstrated in several animal infection models, including a model of AOM. Taken together, these data provide experimental support for the use of single-dose azithromycin for the treatment of AOM in children. In 2 accompanying papers in this supplement, Arguedas et al25 and Block et al26 reported on their investigations of the clinical efficacy and tolerability of single-dose azithromycin for treating AOM in children.

Footnotes

Reproduction in whole or part is not permitted.

References

- 1.Zithromax (azithromycin) [package insert]. New York: Pfizer Inc; 2002.

- 2.Craig W.A. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: Rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1–10. doi: 10.1086/516284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foulds G., Shepard R.M., Johnson R.B. The pharmacokinetics of azithromycin in human serum and tissues. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25(Suppl A):73–82. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.suppl_a.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gladue R.P., Snider M.E. Intracellular accumulation of azithromycin by cultured human fibroblasts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1056–1060. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlier M.B., Garcia-Luque I., Montenez J.P. Accumulation, release and subcellular localization of azithromycin in phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells in culture. Int J Tissue React. 1994;16:211–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raulston J.E. Pharmacokinetics of azithromycin and erythromycin in human endometrial epithelial cells and in cells infected with Chlamydia trachomatis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:765–776. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pascual A., Rodriguez-Bano J., Ballesta S. Azithromycin uptake by tissue cultured epithelial cells. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:293–295. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gladue R.P., Bright G.M., Isaacson R.E., Newborg M.F. In vitro and in vivo uptake of azithromycin (CP-62,993) by phagocytic cells: Possible mechanism of delivery and release at sites of infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:277–282. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wildfeuer A., Laufen A., Zimmermann T. Uptake of azithromycin by various cells and its intracellular activity under in vivo conditions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:75–79. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hand W.L., Hand D.L. Characteristics and mechanisms of azithromycin accumulation and efflux in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;18:419–425. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandell G.L., Coleman E. Uptake, transport, and delivery of antimicrobial agents by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1794–1798. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.6.1794-1798.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Retsema J.A., Bergeron J.M., Girard D. Preferential concentration of azithromycin in an infected mouse thigh model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31(Suppl E):5–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_e.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foulds G., Johnson R.B. Selection of dose regimens of azithromycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31(Suppl E):39–50. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_e.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pukander J., Rautianen M. Penetration of azithromycin into middle ear effusions in acute and secretory otitis media in children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37(Suppl C):53–61. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.suppl_c.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amsden G.W., Gray C.L. Serum and WBC pharmacokinetics of 1500 mg of azithromycin when given either as a single dose or over a 3 day period in healthy volunteers. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;47:61–66. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein F.W., Emirian M.F., Coutrot A., Acar J.F. Bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity of azithromycin against Haemophilus influenzae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25(Suppl A):25–28. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.suppl_a.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girard A.E., Cimochowski C.R., Faiella J.A. The comparative activity of azithromycin, macrolides and amoxycillin against streptococci in experimental infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31(Suppl E):29–37. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_e.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babl F.E., Pelton S.I., Li Z. Experimental acute otitis media due to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: Comparison of high and low azithromycin doses with placebo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2194–2199. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2194-2199.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen R., Reinert P., de la Rocque F. Comparison of two dosages of azithromycin for three days versus penicillin V for ten days in acute group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:297–303. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200204000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drusano G.L., Craig W.A. Relevance of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in the selection of antibiotics for respiratory tract infections. J Chemother. 1997;9(Suppl 3):38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig W.A. The hidden impact of antibacterial resistance in respiratory tract infection. Re-evaluating current antibiotic therapy. Respir Med. 2001;95(Suppl A):S12–S19. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(01)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craig WA, Keim S, Andes DR. Free drug 24-hr AUC/MIC is the PK/PD target that correlates with in vivo efficacy of macrolides, azalides, ketolides and clindamycin. 42nd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; September 27–30, 2002; San Diego, California. Abstract A-1264.

- 23.Craig W.A. Postantibiotic effects and dosing of macrolides, azalides and streptogramins. In: Zinner S.H., Young L.S., Acar J.F., New H.C., editors. Expanding Indications of the New Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1997. pp. 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Girard D, Finegan SM, Cimochowski CR, et al. Accelerated dosing of azithromycin in preclinical infection models. 102nd General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, May 19–23, 2002; Salt Lake City, Utah. Abstract A-57.

- 25.Arguedas A., Loaiza C., Perez A. A pilot study of single-dose azithromycin versus 3-day azithromycin or single-dose ceftriaxone for uncomplicated acute otitis media in children. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2003;64(Suppl A):AXX–AXX. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Block S.L., Arrieta A., Seibel M. Single-dose (30 mg/kg) azithromycin compared with 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate for the treatment of uncomplicated acute otitis media: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2003;64(Suppl A):AXX–AXX. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]