Abstract

Objectives

The objectives of the study were to use persona-driven and scenario-based design methods to create a conceptual information system design to support public health nursing.

Design and Sample

We enrolled 19 participants from two local health departments to conduct an information needs assessment, create a conceptual design, and conduct a preliminary design validation.

Measures

Interviews and thematic analysis were used to characterize information needs and solicit design recommendations from participants. Personas were constructed from participant background information, and scenario-based design was used to create a conceptual information system design. Two focus groups were conducted as a first iteration validation of information needs, personas, and scenarios.

Results

Eighty-nine information needs were identified. Two personas and 89 scenarios were created. Public health nurses and nurse managers confirmed the accuracy of information needs, personas, scenarios, and the perceived usefulness of proposed features of the conceptual design. Design artifacts were modified based on focus group results.

Conclusion

Persona-driven design and scenario-based design are feasible methods to design for common work activities in different local health departments. Public health nurses and nurse managers should be engaged in the design of systems that support their work.

Keywords: design reuse, information systems, public health informatics, public health nursing, public health systems, scenario-based design

The design, development, and implementation of integrated information systems that allow for analysis, visualization, and exchange of data between and across public health jurisdictions for different stakeholders in support of public health work has been identified as a priority research area for public health informatics (Massoudi et al., 2012). Current efforts to standardize the formats and uses of electronic medical record data are intended to enhance interoperability and facilitate data exchange between public health systems and clinical information systems (Williams, Mostashari, Mertz, Hogin, & Atwal, 2012). Other efforts specifically aim to support the work of public health nurses (PHNs) through the implementation of data standards and information infrastructure (Issel, Bekemeier, & Kneipp, 2012; Monsen, Bekemeier, P. Newhouse, & Scutchfield, 2012). Despite these efforts and numerous studies of the information needs of the public health workforce (Revere et al., 2007; Turner, Stavri, Revere, & Altamore, 2008), public health workers must interact with multiple disparate systems that do not interoperate or exchange data (Staes et al., 2009). As the largest professional group of the public health workforce (University of Michigan Center of Excellence in Public Health Workforce Studies & University of Kentucky Center of Excellence in Public Health Workforce Research and Policy, 2012), PHNs are strongly affected by information system designs that do not fit their work. During emergencies, PHNs play a key role (Katz, Staiti, & Mckenzie, 2006) and require information systems that support continuity of operations before, during, and after public health surge events (Rebmann, Carrico, & English, 2008). Routine operations to deliver public health services are characterized by the need to manage small emergencies on a regular basis (Reeder & Turner, 2011). With recent initiatives to accelerate the adoption of electronic medical records, there are higher expectations for information exchange between clinical care and public health information systems. Thus, there is a pressing need for integrated information systems designed to seamlessly support PHNs and public health nurse managers (NMs) during normal and emergency operations.

Background

Best practices recommend the use of qualitative design approaches that contextualize the fit of practitioners, tasks, systems, and work environments in the early stages of health informatics projects to improve usability and reduce obstacles to system adoption (Yen & Bakken, 2011). Prior research has explored support of public health work for continuity of operations planners (Reeder & Demiris, 2010) and managers of multiple public health centers (Reeder & Turner, 2011). To our knowledge, there have been few cross-jurisdictional studies to create designs that support the information needs and work activities of PHNs and NMs. To bridge the identified gap in operational support for the work of public health nursing, we conducted an information needs study and preliminary validation of a conceptual information system design by engaging participants from two local health departments (LHDs) using participatory design (PD).

The term “information need” has many different meanings in studies of information science, computer science, organizational decision making, marketing, media, and health communication (Wilson, 1994). This also holds true for studies of health informatics. Therefore, we synthesized a definition of information need based on Friedman’s Fundamental Theorem of Biomedical Informatics (Friedman, 2009) and prominent design (Carroll, 2000) usability (Davis, 1989) and information behavior (Case, 2002) sources. For purposes of this study, our definition of an information need is a person’s recognition that an information system should help her or him know something, learn something, or do something better than if those same activities were performed without the information system.

Research questions

This study had two research questions. The first was what are the information needs of PHNs and NMs involved in the delivery of health services through home visits? The second was how do PHNs and NMs from different LHDs perceive a conceptual integrated information system design created to support their information needs?

Methods

Design and sample

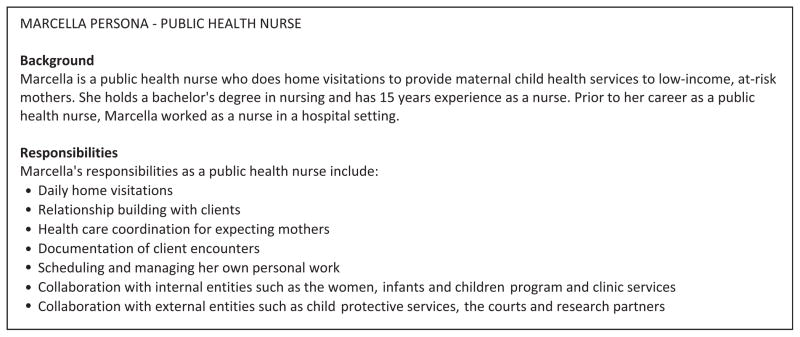

This was a three aim information design study that engaged 19 participants from 2 LHDs using PD (Blomberg, Giacomi, Mosher, & Swenton-Wall, 1993). See Figure 1 for an overview of the study flow. Study aims were to characterize information needs of public health nurses and nurse managers; create a conceptual design of an integrated information system; and conduct a preliminary validation of the conceptual design.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Illustrating Data Collection, Design, and Validation Steps

The study setting consisted of two LHDs on the West Coast of the United States. Agency A is a medium-sized LHD and serves a population of more than 400,000 that is both urban and rural, whereas Agency B is a large LHD and serves an urban population of about 1.9 million. Participants were drawn from both LHDs. Inclusion criteria included to currently hold or have held a senior clinical or clerical position at a LHD; to be currently involved in, or have past experience, with activities related to the delivery of public health services at a LHD; and to be 21 years of age or older. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Washington. Participants provided informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. In some cases, unique job titles that contain specific information that could identify individuals have been changed to generic titles.

Participatory design is an approach that uses qualitative methods to directly engage people in the design of systems they will use (Blomberg et al., 1993). PD is part of a proposed strategy to develop reusable design knowledge in public health settings (Reeder, Hills, Demiris, Revere, & Pina, 2011). PD is flexible in that stakeholders can be engaged at various levels of commitment based on available resources. Given the constraints of work responsibilities and schedules, our participants could not engage in a time-intensive design project. Therefore, we chose interviews at the LHDs to solicit information needs and design feedback from individual participants at a time of their convenience. On-site interviews allowed participants to demonstrate interactions and problems with individual information systems on an ad hoc basis during interviews. Likewise, they were able to provide documents related to organizational policies and vendor systems under consideration for purchase as topics arose during discussion.

Using information needs identified from interviews and scenario-based design, the primary author created a conceptual information system design that included scenarios of use and personas. Scenario-based design focuses on the activities of the people who will use an information system rather than the system itself or the capabilities of technology (Carroll, 2000). Scenarios of use are concrete narratives that are easily understood by people who perform work in nontechnical domains; they provide a design vocabulary for laypersons involved in the design process (Filippidou, 1998). Thus, scenarios can be assessed by the target audience of an information system before development of the actual system begins. A persona is a description of a hypothetical individual that typifies a person who will use an information system (Pruitt & Grudin, 2003). Personas are used to concretize the idea of an individual stakeholder and envision the ways she might interact with the system under design. For efficiency in our validation step, we chose focus groups as a method to simultaneously collect evaluation data from multiple participants about information needs, scenarios of use, and personas.

Measures

Interviews

Nineteen semistructured interviews were conducted at Agency A (n = 14) and Agency B (n = 5) to identify information needs and design recommendations. Fewer interviews were conducted at Agency B because members of the research team had spent the previous 2 years doing on-site research at multiple facilities within Agency B (Reeder & Demiris, 2010; Reeder & Turner, 2011). Interview guide questions focused on participant background, responsibilities, routine tasks and activities, barriers to work, current information systems in use, and ways participants managed information. A version of the interview guide was piloted with nine participants during a separate design project in 2009 (Reeder & Demiris, 2010; Reeder & Turner, 2011). Fourteen of the interviews were conducted by the first author and an assistant; the remaining five interviews were conducted by the first author. All 19 interviews were recorded using a digital audio recorder and transcribed verbatim.

Focus groups

After interview analysis and the design process (described below), two focus groups (Krueger & Casey, 2000) were conducted to validate the conceptual design in June, 2010. One focus group was conducted at Agency A (n = 4) and the other was conducted at Agency B (n = 5). Focus group participants held the roles of public health nurse (n = 5), nurse manager (n = 2), medical nutritionist (n = 1), and nursing student (n = 1). Focus groups lasted about 90 min and were conducted by two authors. The first author acted as moderator while the second author acted as observer and note taker. Participants were given artifacts comprising the conceptual design in the form of printed copies of information needs, scenarios of use, and proposed reports. Focus group guide questions were concerned with the accuracy, usefulness, benefits, and concerns of information needs, personas, and scenarios. Participants were prompted to provide feedback to improve designs. Focus groups were recorded using a digital audio recorder and transcribed verbatim.

Analytic strategy

Interview analysis

For Aim 1, more interviews were conducted at Agency A to gain an understanding of organizational context, as described above. Seven of the Agency A interviews were conducted with participants who had roles in upper level administrative, network administration, finance, and human resources. After a reading of all transcripts, these seven roles were judged to have less direct interactions with PHN and NM roles and were excluded from the design effort. The remaining 12 interview transcripts were loaded into NVivo 8 qualitative analysis software (QSR International, 2008) for analysis. Participants held the roles of public health nurse (n = 3), nurse manager (n = 5), and health administrator (n = 4). NMs had work experience performing home visits as PHNs, with the exception of one.

Three interviews were selected at random and coded by the first and second authors as a test of interrater reliability. Thematic coding was data driven according to line-level and thematic coding practices (Boyatzis, 1998; Miles & Huberman, 1994) to identify information needs. Starting with no codes, both authors independently created codes then met to reconcile differences in coding. Differences were reconciled through discussion until agreement was reached about the meaning and application of each code. This process was repeated for the second transcript. The codebook was reviewed by a public health expert as a test of content validity. A third transcript was independently coded by both coders to complete the interrater reliability test. The remaining transcripts were coded by the first author.

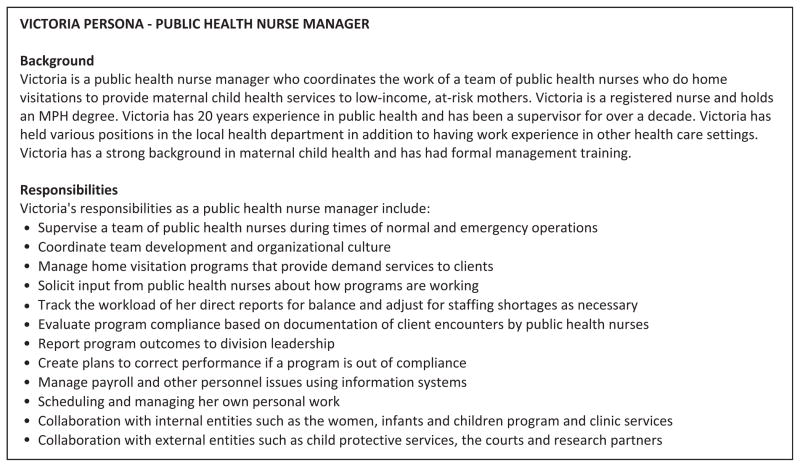

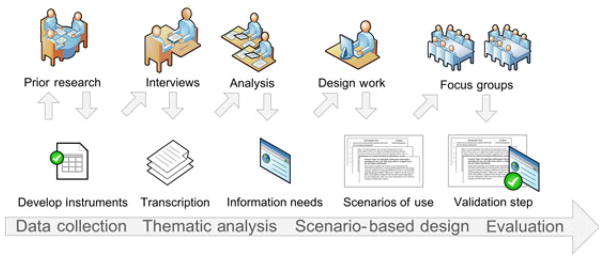

Design process

For Aim 2, the first author conducted the design process in consultation with the last author. To construct PHN and NM personas (see Figure 2), we summarized and aggregated information related to experience, education, and job responsibilities for PHNs and NMs. To create scenarios of use, we used the information needs from Aim 1 and participant design recommendations identified from interviews. The scenarios of use constitute descriptions of work activities that satisfy the goals of each information need. Using the two personas, scenarios of use were matched to the work of PHNs and NMs.

Figure 2.

“Marcella”—A Public Health Nurse Persona

Focus group analysis

For Aim 3, focus group transcripts were loaded into NVivo 8 qualitative analysis software (QSR International, 2008). Data analysis of focus group transcripts was purpose driven (Krueger & Casey, 2000). A straightforward content analysis was conducted by the first author to verify accuracy of information needs, perceptions that scenarios supported information needs as goals of work, acceptability of the design, and participants’ suggestions for revisions. Results from both focus groups were compared to identify agreement and disagreement between LHDs (Krueger & Casey, 2000). The second author reviewed the results of the focus group analysis as a test of face validity.

Results

We describe the validated information needs, personas, and scenarios that comprise the conceptual design. The proposed system is intended to meet three objectives: (a) to support secure, mobile work, and secure communication through a variety of devices; (b) to facilitate the activities of public health nurses and nurse managers as they provide and document services to clients; and (c) to help to manage workload and resources during normal and emergency operations. The conceptual design is meant to support one-time entry of referral and client documentation in an integrated system that allows the sharing of data within a LHD as well as to external partners. In addition, the conceptual design is meant to allow the import of referral and client data from external partners.

Information needs

Analysis of interview transcripts led to the identification of 89 information needs specific to the work of PHNs and NMs. There was a large degree of overlap in information needs for roles related to administration of personal workload, management of referrals, general communication, and emergency communication. Information needs related to delivery of client services were almost exclusively those of PHNs. NMs had information needs related to workforce administration and continuity of operations planning that were exclusive to their job role. Table 1 shows descriptive information for information needs by activity type and the number of information needs identified for the individual roles of PHN and NM. Information needs are grouped into seven different activity types.

TABLE 1.

Number of Information Needs by Activity Type and Role

| Activity type | Description | Total | PHNs | NMs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative—self | Administration or organization of personal workload | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Client service/documentation | Delivery of client services or documentation of delivery of services | 37 | 36 | 1 |

| Management of referrals | Accepting or sending referrals from/to internal programs and external partners | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| General communication | Communications during normal operations within or external to the health department | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Administrative—workforce | Administration or organization of staff workload | 19 | 0 | 19 |

| Emergency communication | Communications during emergency operations within or external to the LHD | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Continuity of operations planning | Planning or managing operations during routine and emergency operations | 4 | 0 | 4 |

Personas

Two named personas for a public health nurse —“Marcella”—and a nurse manager—“Victoria”—are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 3.

“Victoria”—A Public Health Nurse Manager Persona

Scenarios of use

Table 2 shows examples of three selected scenarios, the information need each supports, and the persona that engages in the work activity described by the scenario. The mobile access to office network information need and scenario is common to both the “Victoria” and “Marcella” personas.

TABLE 2.

Selected Examples of Information Needs and Scenarios of Use by Persona

| Information need | Scenario of use | Marcella | Victoria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile access to office network | Marcella needs to download some files from her personal folder on the network. She logs on to the office network remotely, finds the files she needs, and transfers them to her laptop | ✓ | ✓ |

| View information from the State Immunization Registry | Marcella is seeing a client who has questions about the date of her child’s last vaccinations. Marcella finds the child’s record in the information system and views vaccination information from the State Immunization Registry to answer the client’s questions | ✓ | |

| View a map of all client appointments as scheduled for all staff members | Victoria wants to see where all of her nurses are working on a given day. She logs into the information system and goes to the mapping feature. She selects the current day and all the nurses on her team to see a map with pins labeled with client locations and scheduled visit times, the nurse assigned to each client, and routes drawn between locations | ✓ |

Focus group results

Focus group participants from both LHDs validated the conceptual design (information needs, personas, and scenarios of use) as accurate with some suggestions for revisions. Participants suggested minor revisions to make the personas more accurately reflect descriptions of real-world practitioners. All recommendations suggested by participants were incorporated into the personas and other design artifacts. Design feedback and comparisons of the differences between the two sites are described below.

There was a high degree of agreement between participants from both LHDs about common work activities as indicated by validation of scenarios for client service and documentation, workload tracking, and staff management activities. One key theme was the need for managers to access overall case load as recognized by participants in both focus groups. A second key theme was emphasis on the need for a dynamic flexible system to accommodate frequent changes in documentation due to changes in work funding. A third key theme was the need for a system that could flexibly link outcomes of services delivered to clients to reduce workload for reporting to sponsors. Participants were often required to perform duplicate data entry using multiple electronic and paper-based systems. Thus, a fourth key theme was the idea of support for one-time data entry of client data to facilitate collaboration and reuse of data. This theme is illustrated by the following quote from an Agency A participant: “It would be nice to receive the referral, and put it once and then have [it] in the system”.

The idea of real-time documentation was highly valued by participants from both LHDs for efficiency, convenience, and access of timely data from remote locations. Barriers of current documentation processes were described by a participant from Agency B: “If [the obstetrics nurse] were to see an OB client and make a note about it, there’s no way when you’re out in the field that you have any way to see what that would be.” Participants wanted the ability to see views of integrated data from other divisions. One participant from Agency B was impressed by this proposed feature of the conceptual design. When reading the scenarios, she commented: “I’m amazed that she can check the pharmacy. She can check the lab results. That would be good… We can’t do any of that. It would work. It would be good customer service.” Similarly, support for integrated scheduling was a highly valued proposed feature of the conceptual design, prompting one participant from Agency A to remark: “That would be really nice. Otherwise you do your paper calendar and then come back here and enter all the data on the computer.” Another popular proposed feature was the ability to communicate with and see data from external providers, particularly for managing client referrals. Participants found the idea of a reports function and proposed list of reports useful. The importance of basic demographic reporting and custom reporting to determine population outcomes of service delivery was emphasized in both LHDs.

There was general consensus in both LHDs that the system should run on a laptop computer. However, some participants indicated that they did not take a laptop into clients’ homes because it would be disruptive to the home visit. These participants expressed a preference for documenting visits in their cars. Some participants also expressed a desire to have system features available on a smart phone.

Some differences between sites emerged when it came to requested features and the emphasis of design efforts. In Agency A, requested features included a work flow reminder system that would prompt the nurse to finish the steps of a protocol such as printing, filing, or sending documentation to another provider; an activity coding feature for billable units with a drop-down list of common codes; alerts for conditions such as penicillin allergies; the ability to set alerts for tracking of client conditions, such as depression scores; and a feature to visualize body mass index with regard to growth curves.

Agency A participants emphasized the need to correctly model work flow for referrals and client record creation. In many cases, nurses did not create the client records, but reviewed them after creation by clerical staff. They expressed frustration with the work flow of the current client record creation process. The proposed features for requesting interpretation services did not fit the interpretation process of Agency A. There was disagreement about whether or not to support printing of standardized forms. One concern was that continued support of printed forms might be a barrier to the realization of a paperless system.

Agency B PHN participants wanted a feature to personally manage individual professional certifications similar to the proposed feature available to managers. In addition, they emphasized the need to support different organizational implementations of programs for maternity support services and WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic). Agency B participants also strongly emphasized the need to support face-to-face encounters using mobile technology rather than nursing telehealth visits.

Discussion

The aims of this study were to characterize the information needs of public health nursing work; to create a conceptual information system design that could be implemented in different LHDs; and to conduct a preliminary validation of the conceptual design. One benefit of this effort is the description and analysis of ways to reduce disruptions in the delivery of public health services to maintain continuity of operations during critical incidents such as infectious disease outbreaks, earthquakes, floods, etc. Another benefit of this effort is identification of ways to support the work of public health nurses and nurse managers during day-to-day operations.

In both LHDs, the findings of our study confirmed the need for technology that supports common work activities and frequent changes in work, one-time data entry, real-time documentation, communication and integrated data views, integrated scheduling, communication with external providers, and customizable reporting. Prior research has sought to identify standardized public health work tasks (Merrill, Keeling, & Gebbie, 2009) and has identified some of the same information needs (Revere et al., 2007). For instance, Revere et al. characterized the information needs of public health practitioners related to general information-seeking behavior for unknown information in a systematic review (Revere et al., 2007). While our definition of information need differs from Revere et al.’s, and the activities of public health nurses are often concerned with the need to use and manage known information, there are similarities between our findings and those of the systematic review. In both cases, there was an explicit need for timely, up-to-date information that is reliable and easily accessed. Both studies found the need for centralized access to data that are summarized and filtered for viewing. Both studies identified the need to connect with other professionals. In the case of our study, other professionals included community partners. In the case of the systematic review, other professionals involved connecting to public health experts for answers to questions. In a study conducted in a smaller LHD, Turner et al. found that information needs varied by role, but that public health nurses rely heavily on colleagues for information, need access to timely, up-to-date information sources to assist with client care, and require technology and inter-net access to support their work (Turner et al., 2008). The findings from these studies suggest commonalities in information needs across public health environments. However, to our knowledge, our study is the first to incorporate these information needs into the conceptual design of an integrated system to support the work of public health nurses at two different LHDs.

Participants in focus groups at both LHDs suggested additional details for persona descriptions and features for the conceptual design that we did not identify through interview data. These requests for new features as the project progressed confirm the need for successive design iterations that engage public health nurses in PD. In addition, the confirmation of common work activities between LHDs supports the idea of developing reusable design knowledge for public health work (Reeder et al., 2011).

The scope of this study was limited by available resources and geographically dispersed organizations. The implications of greater resources would be more active engagement of stakeholders, more rapid and numerous design iterations, and more complete descriptions of public health nursing work to inform system design. In addition, given differences in the way public health services are delivered in different countries, efforts to translate this conceptual design may encounter barriers in translation to settings outside the United States.

Implications and recommendations

The public health nurses involved in this study delivered services via home visits to low-income, at-risk mothers through a number of different programs. However, PHN impact on their clients extends beyond the immediate services they provide in the home setting because of PHN interactions at a community level with community and nonprofit organizations, hospital and nonhospital providers, universities, and municipal courts. If implemented as a working system, the conceptual design from this study has the potential to boost the impact of work that PHNs already do. Not only is there the potential to increase the work satisfaction of PHNs while reducing costs through elimination of duplicated work, there is the potential bonus of realizing integrated service coordination by connecting LHDs to their external partner networks.

The decision to conduct research in this topic area was originally motivated by a perceived need for integrated, mobile support for public health work activities in light of threats such as the global H1N1 influenza outbreak and the increased frequency of disasters worldwide. However, as we explored information design research in this context, the lesson we learned is that limited resources create an environment in which public health practitioners are forced to deal with small emergencies on a frequent basis. Put differently, to support public health operations during emergencies is quite simply to support public health operations.

Another lesson learned is that public health nurses and nurse managers are willing to engage in the design of technology that supports their work. This is a testament to our participants’ commitment to practice as most, if not all, were overscheduled and working in an environment defined by years of successive budget cuts. Nevertheless, our participants volunteered their time with the full knowledge that this was an exploratory design study. The implication for informatics research and public health nursing is that there is a willing audience waiting to be engaged to design, develop, and evaluate better systems that support their work. This study demonstrates that persona-driven design and scenario-based design are feasible methods to engage public health nurses and nurse managers from different LHDs to design for common work activities.

The conceptual design developed in this study is an attempt to characterize and validate the information needs and activities of public health nurses through a design representation of an integrated information system. The documented information needs from this study contribute to the general knowledge and theory of the work performed by public health nurses and nurse managers. Larger studies that include formal participant observation, a greater number of study sites, and a comprehensive analysis of policies, licensure, and accreditation requirements at local, state, and national levels are needed to develop a complete model of public health nursing information needs and activities. The ability to transfer and reuse the design knowledge from this study in other contexts will require additional research. In addition, design efforts to identify international differences in information needs and activities are needed. Future work should include developing and testing prototypes designed to support the work of public health nursing.

Acknowledgments

At the time this manuscript was prepared, Dr. Reeder was a postdoctoral fellow affiliated with the Department of Biobehavioral Nursing and Health Systems in the School of Nursing at the University of Washington. This study was conducted as part of Dr. Reeder’s dissertation research during his appointment as a predoctoral fellow in the Department of Medical Education and Biomedical Informatics in the School of Medicine at the University of Washington. This research was supported in part by National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) Training Grant T32NR007106 and National Library of Medicine (NLM) Training Grant T15LM007442. The authors would like to thank our participants for graciously volunteering their time for this study.

References

- Blomberg J, Giacomi J, Mosher A, Swenton-Wall P. Ethnographic field methods and their relation to design. In: Schuler D, Namioka A, editors. Participatory design: Principles and practices. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1993. pp. 123–155. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JM. Five reasons for scenario-based design. Interacting with Computers. 2000;13(1):43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Case DO. Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly. 1989;13(3):319–340. [Google Scholar]

- Filippidou D. Designing with scenarios: A critical review of current research and practice. Requirements Engineering. 1998;3(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman CP. A “Fundamental theorem” of biomedical informatics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2009;16(2):169. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issel LM, Bekemeier B, Kneipp S. A public health nursing research agenda. Public Health Nursing. 2012;29(4):330–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2011.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz A, Staiti AB, Mckenzie KL. Preparing for the unknown, responding to the known: Communities and public health preparedness. Health Affairs. 2006;25(4):946–957. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Massoudi BL, Goodman KW, Gotham IJ, Holmes JH, Lang L, Miner K, et al. An informatics agenda for public health: Summarized recommendations from the 2011 AMIA PHI Conference. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2012;19(5):688–695. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill J, Keeling J, Gebbie K. Toward standardized, comparable public health systems data: A taxonomic description of essential public health work. Health Services Research. 2009;44:1818–1841. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Monsen KA, Bekemeier BP, Newhouse R, Scutchfield FD. Development of a public health nursing data infrastructure. Public Health Nursing. 2012;29(4):343–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2011.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt J, Grudin J. Personas: Practice and theory. Proceedings of the 2003 conference on designing for user experiences; San Francisco, CA: ACM; 2003. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVivo 8. Australia: QSR International; 2008. Retrieved from www.qsrinternational.com. [Google Scholar]

- Rebmann T, Carrico R, English JF. Lessons public health professionals learned from past disasters. Public Health Nursing. 2008;25(4):344–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder B, Demiris G. Building the PHARAOH framework using scenario-based design: A set of pandemic decision-making scenarios for continuity of operations in a large municipal public health agency. Journal of Medical Systems. 2010;34(4):735–739. doi: 10.1007/s10916-009-9288-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder B, Hills R, Demiris G, Revere D, Pina J. Reusable design: A proposed approach to Public Health Informatics system design. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder B, Turner AM. Scenario-based design: A method for connecting information system design with public health operations and emergency management. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2011;44(6):978–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revere D, Turner AM, Madhavan A, Rambo N, Bugni PF, Kimball A, et al. Understanding the information needs of public health practitioners: A literature review to inform design of an interactive digital knowledge management system. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2007;40(4):410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staes CJ, Xu W, Lefevre SD, Price RC, Narus SP, Gundlapalli A, et al. A case for using grid architecture for state public health informatics: The Utah perspective. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2009;9(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner AM, Stavri Z, Revere D, Altamore R. From the ground up: Information needs of nurses in a rural public health department in Oregon. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2008;96(4):335–342. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.96.4.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Michigan Center of Excellence in Public Health Workforce Studies & University of Kentucky Center of Excellence in Public Health Workforce Research and Policy. Strategies for enumerating the US Government public health workforce. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.phf.org. [Google Scholar]

- Williams C, Mostashari F, Mertz K, Hogin E, Atwal P. From the Office of the National Coordinator: The strategy for advancing the exchange of health information. Health Affairs. 2012;31(3):527–536. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TD. Information needs and uses: Fifty years of progress. In: Vickery BC, editor. Fifty years of information progress: A Journal of Documentation review. London: Aslib; 1994. pp. 15–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yen PY, Bakken S. Review of health information technology usability study methodologies. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011;19(3):413–422. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]