Abstract

We assessed 12-month prevalence and incidence data on sexual victimization in 5 federal surveys that the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation conducted independently in 2010 through 2012. We used these data to examine the prevailing assumption that men rarely experience sexual victimization. We concluded that federal surveys detect a high prevalence of sexual victimization among men—in many circumstances similar to the prevalence found among women. We identified factors that perpetuate misperceptions about men’s sexual victimization: reliance on traditional gender stereotypes, outdated and inconsistent definitions, and methodological sampling biases that exclude inmates. We recommend changes that move beyond regressive gender assumptions, which can harm both women and men.

The sexual victimization of women was ignored for centuries. Although it remains tolerated and entrenched in many pockets of the world, feminist analysis has gone a long way toward revolutionizing thinking about the sexual abuse of women, demonstrating that sexual victimization is rooted in gender norms1 and is worthy of social, legal, and public health intervention. We have aimed to build on this important legacy by drawing attention to male sexual victimization, an overlooked area of study. We take a fresh look at several recent findings concerning male sexual victimization, exploring explanations for the persistent misperceptions surrounding it. Feminist principles that emphasize equity, inclusion, and intersectional approaches2; the importance of understanding power relations3; and the imperative to question gender assumptions4 inform our analysis.

To explore patterns of sexual victimization and gender, we examined 5 sets of federal agency survey data on this topic (Table 1). In particular, we show that 12-month prevalence data from 2 new sets of surveys conducted, independently, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) found widespread sexual victimization among men in the United States, with some forms of victimization roughly equal to those experienced by women.

TABLE 1—

US Federal Agency Surveys of Sexual Victimization Using Probability Samples

| Study | Year of Study | Conducted by | Sample | No. |

| National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) | 2010 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | Nationally representative telephone survey of 12 mo and lifetime prevalence data on sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence | 16 507 |

| National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) | 2012 | Bureau of Justice Statistics | Longitudinal survey of US households | 40 000 households |

| ∼75 000 | ||||

| Uniform Crime Report (UCR) | 2012 | Federal Bureau of Investigation | NA (UCR is a cooperative statistical effort whereby 18 000 city, university, and college, county, state, tribal, and federal law enforcement agencies report data on crimes brought to their attention.) | NA |

| Sexual Victimization in Prisonsa and Jails Reported by Inmates; National Inmate Survey (NIS 2011–12) | 2011–2012 | Bureau of Justice Statistics | Probability sample of state and federal confinement facilities and random sampling of inmates within selected facilities | 92 449 |

| Sexual Victimization in Juvenile Facilitiesa Reported by Youth; National Survey of Youth in Custody (NSYC 2012) | 2012 | Bureau of Justice Statistics | Multistage stratified survey of facilities in each state of the United States and random sample of youths within selected facilities | 8707 |

Note. NA = not available.

In these reports, 12-month prevalence refers to 12 months, or shorter if the respondent has been in the facility for less than 12 months.

Despite such findings, contemporary depictions of sexual victimization reinforce the stereotypical sexual victimization paradigm, comprising male perpetrators and female victims. As we demonstrate, the reality concerning sexual victimization and gender is more complex. Although different federal agency surveys have different purposes and use a wide variety of methods (each with concomitant limitations), we examined the findings of each, attempting to glean an overall picture. This picture reveals alarmingly high prevalence of both male and female sexual victimization; we highlight the underappreciated findings related to male sexual victimization.

For example, in 2011 the CDC reported results from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), one of the most comprehensive surveys of sexual victimization conducted in the United States to date. The survey found that men and women had a similar prevalence of nonconsensual sex in the previous 12 months (1.270 million women and 1.267 million men).5 This remarkable finding challenges stereotypical assumptions about the gender of victims of sexual violence. However unintentionally, the CDC’s publications and the media coverage that followed instead highlighted female sexual victimization, reinforcing public perceptions that sexual victimization is primarily a women’s issue.

We explore 3 factors that lead to misperceptions concerning gender and sexual victimization. First, a male perpetrator and female victim paradigm underlies assumptions about sexual victimization.6 This paradigm serves to obscure abuse that runs counter to the paradigm, reinforce regressive ideas that portray women as victims,7 and stigmatize sexually victimized men.8 Second, some federal agencies use outdated definitions and categories of sexual victimization. This has entailed the prioritization of the types of harm women are more likely to experience as well as the exclusion of men from the definition of rape. Third, the data most widely reported in the press are derived from household sampling. Inherent in this is a methodological bias that misses many who are at great risk for sexual victimization in the United States: inmates, the vast majority of whom are male.9,10

We call for the consistent use of gender-inclusive terms for sexual victimization, objective reporting of data, and improved methodologies that account for institutionalized populations. In this way, research and reporting on sexual victimization will more accurately reflect the experiences of both women and men.

MALE PERPETRATOR AND FEMALE VICTIM PARADIGM

The conceptualization of men as perpetrators and women as victims remains the dominant sexual victimization paradigm.11 Scholars have offered various explanations for why victimization that runs counter to this paradigm receives little attention. These include the ideas that female-perpetrated abuse is rare or nonexistent,12 that male victims experience less harm,8 and that for men all sex is welcome.13 Some posit that because dominant feminist theory relies heavily on the idea that men use sexual aggression to subordinate women,14 findings perceived to conflict with this theory, such as female-perpetrated violence against men, are politically unpalatable.15 Others argue that researchers have a conformity bias, leading them to overlook research data that conflict with their prior beliefs.16

We have interrogated some of the stereotypes concerning gender and sexual victimization, and we call for researchers to move beyond them. First, we question the assumption that feminist theory requires disproportionate concern for female victims. Indeed, some contemporary gender theorists have questioned the overwhelming focus on female victimization, not simply because it misses male victims but also because it serves to reinforce regressive notions of female vulnerability.17 When the harms that women experience are held out as exceedingly more common and more worrisome, this can perpetuate norms that see women as disempowered victims,7 reinforcing the idea that women are “noble, pure, passive, and ignorant.”13(p1719)

Related to this, treating male sexual victimization as a rare occurrence can impose regressive expectations about masculinity on men and boys. The belief that men are unlikely victims promotes a counterproductive construct of what it means to “be a man.”18 This can reinforce notions of naturalistic masculinity long criticized by feminist theory, which asserts that masculinity is culturally constructed.19 Expectations about male invincibility are constraining for men and boys; they may also harm women and girls by perpetuating regressive gender norms.

Another common gender stereotype portrays men as sexually insatiable.13 The idea that, for men, virtually all sex is welcome likely contributes to dismissive attitudes toward male sexual victimization. Such dismissal runs counter to evidence that men who experience sexual abuse report problems such as depression, suicidal ideation, anxiety, sexual dysfunction, loss of self-esteem, and long-term relationship difficulties.20

A related argument for treating male victimization as less worrisome holds that male victims experience less physical force than do female victims,21 the implication being that the use of force determines concern about victimization. This rationale problematically conflicts with the important feminist-led movement away from physical force as a defining and necessary component of sexual victimization.22 In addition, a recent multiyear analysis of the BJS National Crime Victim Survey (NCVS) found no difference between male and female victims in the use of a resistance strategy during rape and sexual assault (89% of both men and women did so). A weapon was used in 7% of both male and female incidents, and although resultant injuries requiring medical care were higher in women, men too experienced significant injuries (12.6% of females and 8.5% of males).23

Portraying male victimization as aberrant or harmless also adds to the stigmatization of men who face sexual victimization.8 Sexual victimization can be a stigmatizing experience for both men and women. However, through decades of feminist-led struggle, fallacies described as “rape myths”24 have been largely discredited in American society, and an alternative narrative concerning female victimization has emerged. This narrative teaches that, contrary to timeworn tropes, the victimization of a woman is not her fault, that it is not caused by her prior sexual history or her choice of attire, and that for survivors of rape and other abuse, speaking out against victimization can be politically important and personally redemptive.

For men, a similar discourse has not been developed. Indeed contemporary social narratives, including jokes about prison rape,25 the notion that “real men” can protect themselves,8 and the fallacy that gay male victims likely “asked for it,”26 pose obstacles for males coping with victimization. A male victim’s sexual arousal, which is not uncommon during nonconsensual sex, may add to the misapprehension that the victimization was a welcome event.27 Feelings of embarrassment, the victim’s fear that he will not be believed, and the belief that reporting itself is unmasculine have all been cited as reasons for male resistance to reporting sexual victimization.28 Popular media also reflects insensitivity, if not callousness, toward male victims. For example, a 2009 CBS News report about a serial rapist who raped 4 men concluded, “No one has been seriously hurt.”29

The minimization of male sexual victimization and the hesitancy of victims to come forward may also contribute to a paucity of legal action concerning male sexual victimization. Although state laws have become more gender neutral, criminal prosecution for the sexual victimization of men remains rare and has been attributed to a lack of concern for male victims.30 The faulty assertion that male victimization is uncommon has also been used to justify the exclusion of men and boys in scholarship on sexual victimization.31 Perhaps such widespread exclusion itself causes male victims to assume they are alone in their experience, thereby fueling underreporting.32

Not only does the traditional sexual victimization paradigm masks male victimization, it can obscure sexual abuse perpetrated by women as well as same-sex victimization. We offer a few counterparadigmatic examples. One multiyear analysis of the NCVS household survey found that 46% of male victims reported a female perpetrator.23 Of juveniles reporting staff sexual misconduct, 89% were boys reporting abuse by female staff.33 In lifetime reports of nonrape sexual victimization, the NISVS found that 79% of self-reported gay male victims identified same-sex perpetrators.34

Despite such complexities, as recently as 2012, the National Incident Based Reporting System (a component of the Uniform Crime Reporting Program [UCR]) included male rape victims but still maintained that for victimization to be categorized as rape, at least 1 of the perpetrators had to be of the opposite sex.35 Conversely, under the NISVS definitions, for a female to fall into the “made to penetrate” category, the perpetrating receptive partner must also be female.5 (“Made to penetrate” includes anal penetration by a finger or other object, and a female could therefore be made to penetrate a male.) Additional research and analysis concerning female perpetration and same-sex abuse is warranted but is beyond the scope of this article. For now we simply highlight the concern that reliance on the male perpetrator and female victim paradigm limits understandings, not only of male victimization but of all counterparadigmatic abuse.

DEFINITIONS AND CATEGORIES OF SEXUAL VICTIMIZATION

The definitions and uses of terms such as “rape” and “sexual assault” have evolved over time, with significant implications for how the victimization of women and men is measured. Although the definitions and categorization of these harms have become more gender inclusive over time, bias against recognizing male victimization remains.

When the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) began tracking violent crime in 1930, the rape of men was excluded. Until 2012, the UCR, through which the FBI collects annual crime data, defined “forcible rape” as “the carnal knowledge of a female forcibly and against her will” (emphasis added).36 Approximately 17 000 local law enforcement agencies used this female-only definition for the better part of a century when submitting standardized data to the FBI.37 Meanwhile, the reform of state criminal law on rape, which began in the 1970s and eventually spread to every jurisdiction in the country, revised definitions in numerous ways, including the increased recognition of male victimization. Reforms also broadened definitions to address nonrape sexual assault.38

These state revisions left a mismatch with the limited UCR definition, forcing agencies to send only a subset of reported sexual assault to the FBI. Some localities eventually refused to parse their data according to the biased federal categories. For example, in 2010 Chicago, Illinois, recorded 84 767 reports of forcible rape under UCR, but because they refused to comply with the UCR’s outdated categorization, the FBI did not include Chicago rape data in its national count.39

In 2012 the FBI revised its 80-year-old definition of rape to the following: “the penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim.”40 Although the new definition reflects a more inclusive understanding of sexual victimization, it appears to still focus on the penetration of the victim, which excludes victims who were made to penetrate. This likely undercounts male victimization for reasons we now detail.

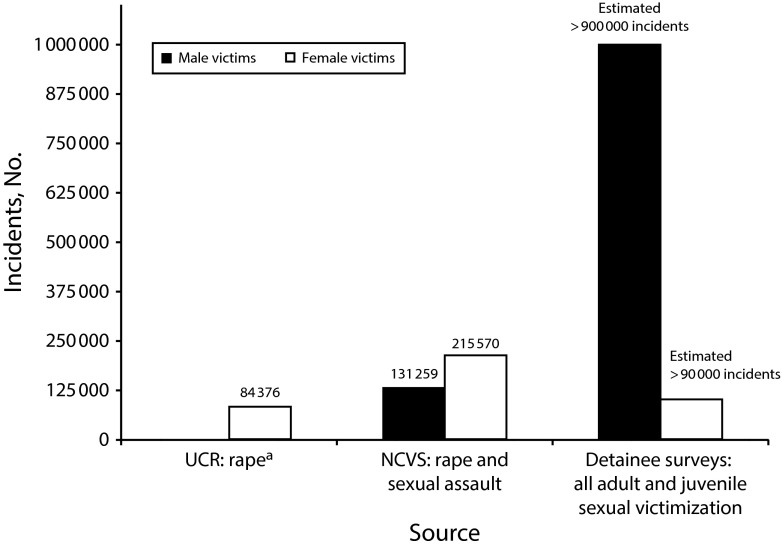

The NISVS’s 12-month prevalence estimates of sexual victimization show that male victimization is underrepresented when victim penetration is the only form of nonconsensual sex included in the definition of rape. The number of women who have been raped (1 270 000) is nearly equivalent to the number of men who were “made to penetrate” (1 267 000).5 As Figure 1 also shows, both men and women experienced “sexual coercion” and “unwanted sexual contact,” with women more likely than men to report the former and men slightly more likely to report the latter.5

FIGURE 1—

Twelve-month sexual victimization prevalence (percentage) among adult population (noninstitutionalized) from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey 2010, and among adult and juvenile detainees from the National Inmate Survey 2011–2012 and the National Survey of Youth in Custody, 2012: United States.

aAmong the 5 federal agency surveys we reviewed, only NISVS collected lifetime prevalence, limiting our ability to compare lifetime data across surveys. It found lifetime prevalence for men as follows: made to penetrate = 4.8%, rape = 1.4%, sexual coercion = 6.0%, and unwanted sexual contact = 11.7%. For women: rape = 18.3%, sexual coercion = 13.0%, and unwanted sexual contact = 27.2%.

bFemale detainees are significantly more likely to be sexually victimized by fellow detainees than are males; a presumably same-sex pattern of abuse that runs counter to the male perpetrator/female victim paradigm.

This striking finding—that men and women reported similar rates of nonconsensual sex in a 12-month period—might have made for a newsworthy finding. Instead, the CDC’s public presentation of these data emphasized female sexual victimization, thereby (perhaps inadvertently) confirming gender stereotypes about victimization. For example, in the first headline of the fact sheet aiming to summarize the NISVS findings the CDC asserted, “Women are disproportionally affected by sexual violence.” Similarly, the fact sheet’s first bullet point stated, “1.3 million women were raped during the year preceding the survey.” Because of the prioritization of rape, the fact sheet failed to note that a similar number of men reported nonconsensual sex (they were “made to penetrate”).41

The fact sheet paints a picture of highly divergent prevalence of female and male abuse, when, in fact, the data concerning all nonconsensual sex are much more nuanced. Unsurprisingly, media outlets then emphasized the material the CDC highlighted in its summary material. The New York Times headline read, “Nearly 1 in 5 Women in U.S. Survey Say They Have Been Sexually Assaulted.”42(pA32)

In addition, the full NISVS report presents data on sexual victimization in 2 main categories: rape and other sexual violence. “Rape,” the category of nonconsensual sex that disproportionately affects women, is given its own table, whereas “made to penetrate,” the category that disproportionately affects men, is treated as a subcategory, placed under and tabulated as “other sexual violence” alongside lesser-harm categories, such as “noncontact unwanted sexual experiences,” which are experiences involving no touching.5

Additionally, much more information is provided about rape than being made to penetrate. The NISVS report gives separate prevalence estimates for completed versus attempted rape and for rape that was facilitated by alcohol or drugs. No such breakdown is given concerning victims who were made to penetrate, although such data were collected. Including these data in the report would avoid suggesting that this form of unwanted sexual activity is somehow less worthy of detailed analysis.1 These various reporting practices may draw disproportionate attention to the sexual victimization of women, implying that it is a more worrisome problem than is the sexual victimization of men.

Prioritizing rape over being made to penetrate may seem an obvious and important distinction at first glimpse. After all, isn’t rape intuitively the worst sexual abuse? But a more careful examination shows that prioritizing rape over other forms of nonconsensual sex is sometimes difficult to justify, for example, in the case of an adult forcibly performing oral sex on an adolescent girl and on an adolescent boy. Under the CDC’s definitions, the assault on the girl (if even slightly penetrated in the act) would be categorized as rape but the assault on the boy would not. According to the CDC, the male victim was “made to penetrate” the perpetrator’s mouth with his penis,5(p17) and his abuse would instead be categorized under the “other sexual violence” heading. We argue that this is neither a useful nor an equitable distinction.

By introducing the term “made to penetrate,” the CDC has added new detail to help understand what happens when men are sexually victimized. But the distinction may obscure more than it elucidates. In contrast to the term “rape,” the term “made to penetrate” is not commonly used. The CDC’s own press release about the survey, for example, uses the word “rape” (or “raped”) 7 times and makes no mention of “made to penetrate.”43 In this way, “rape” is the harm that ultimately captures media attention, funding, and programmatic intervention, whereas “made to penetrate” is relegated to a secondary, somewhat obscure harm.

Similarly, the FBI’s revised UCR definition, although a distinct improvement over the 1929 female-only definition, still seems to maintain an exclusive focus on the victim’s penetration.40 Therefore, to the extent that males experience nonconsensual sex differently (i.e., being made to penetrate), male victimization will remain vastly undercounted in federal data collection on violent crime.5

This focus on the directionality of the act runs counter to the trend toward greater gender inclusivity in sexual victimization definitions over the past 4 decades. The broader and more inclusive term “sexual assault” has replaced the term “rape” in at least 37 states.44 Not only has this change been widespread in legal definitions, but it is now standard practice to avoid the term “rape” in survey questions because of inconsistencies in how respondents perceive this term.21 Some anti–sexual violence activists may resist movement away from a term as compelling and vivid as “rape,” but others have noted that victims who choose another label may do so as a legitimate coping strategy.45

We recognize that when it comes to the impact of sexual victimization, men and women may indeed experience it differently.21 But categorizing the forms of sexual victimization that men typically experience as different and lesser than the forms of victimization that women typically experience would require considered justification. The reasons for continuing such practices would need to outweigh the drawbacks we have enumerated. We do not believe that such justification has been offered in the literature.

We therefore urge federal agencies to use care when collecting and reporting data on sexual victimization to avoid biased categorization. This does not mean that we suggest treating all sexual victimization identically. Nonconsensual penetrative acts (regardless of directionality) may be legitimately distinguished from acts that do not involve penetration. Likewise, harms that do not involve any genital contact whatsoever, such as unwelcome kissing, flashing, and sexual comments, although harmful for some victims, are categorically distinguishable because they do not involve contact with socially inviolable and physically sensitive reproductive parts of the body.

Without seeking to outline an entirely new classification scheme, we posit that “rape” as currently defined by the CDC and the FBI will continue to foster the underrecognition of the extent of male victimization. Terms such as “sexual assault” and “sexual victimization,” if defined in gender-inclusive ways, have the potential to capture the kind of abuse with which federal agencies ought to be concerned. They can be used more consistently and with less gender and heterosexist bias across crime, health, and other surveys. This would facilitate important cross-population analyses that inconsistent definitions now limit.

SAMPLING BIAS

In population-based sexual victimization studies, as in many other areas, researchers use a sampling frame that is restricted to US households. This excludes, among others, those held in juvenile detention, jails, prisons, and immigration detention centers. Because of the explosion of the US prison and jail population to nearly 2.3 million people46 and the disproportionate representation of men (93% of prisoners9 and 87% of those in jail10) among the incarcerated, household surveys—including the closely watched NCVS—miss many men, especially low-income and minority men who are incarcerated at the time the household survey is conducted. Opportunities for intersectional analyses that take race, class, and other factors into account are missed when the incarcerated are excluded. For instance, characteristics such as sexual minority and disability status, including mental health problems, place inmates at risk: among nonheterosexual prison inmates with serious psychological distress, 21% report sexual victimization.47

Of course, surveys of inmate and juvenile populations present a host of ethical, legal, and logistical challenges for surveyors. Sexual victimization in particular is risky for inmates to disclose; those who report abuse may be targeted for retaliation. The challenges of including vulnerable populations are very real, but because inmates are at great risk, their exclusion is especially likely to skew the public understanding of sexual victimization. For example, the NCVS’s household data on rape and sexual assault are widely reported in the media each year but typically without mention of the impact of excluding incarcerated individuals (or other institutionalized or homeless persons).

Recognizing the lack of data concerning incarcerated persons, the 2003 Prison Rape Elimination Act mandates that BJS conduct a regular comprehensive survey about sexual victimization behind bars.48 These results help fill the gap in knowledge concerning sexual victimization in the United States. We reviewed 2 of the recently released reports (Table 1), which provide results from the National Inmate Survey 2011–2012 and the National Survey of Youth in Custody, 2012.

These 2 surveys demonstrate that male and female detainees both experience sexual victimization committed by staff and other inmates and that the prevalence differs by sex (Figure 1). The National Inmate Survey 2011–2012 shows that slightly more men than women in jails and prisons reported staff sexual misconduct, which includes all incidents of sexual contact with staff (12-month prevalence for men in jails = 1.9%, men in prisons = 2.4% vs 1.4% and 2.3%47 for women, respectively). Women in jails and prisons reported more inmate-on-inmate abuse than did men (women in jails = 3.6%, women in prisons = 6.9% vs 1.4% and 1.7% for men, respectively).

In the National Survey of Youth in Custody 2012, about 9.5% of male and female juvenile detainees reported sexual victimization in the 12 months before the interview (or since detained, if < 12 months).33 But gender differences were observed: females were more likely than were males to report sexual victimization by other youths (5.4% vs 2.2%), and males were more likely than were females to report sexual victimization by facility staff (8.2% vs 2.8%).33

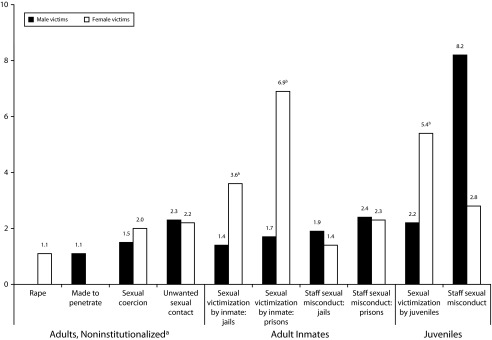

The examination of data from prisons, jails, and juvenile detention institutions reveals a very different picture of male sexual abuse in the United States from the picture portrayed by the household crime data alone. This discrepancy is stark when comparing the detainee findings with those of the NCVS, the longitudinal crime survey of households widely covered in the media each year. The 2012 NCVS’s household estimates indicate that 131 259 incidents of rape and sexual assault were committed against males.49 Using adjusted numbers from the detainee surveys, we roughly estimate that more than 900 000 sexual victimization incidents were committed against incarcerated males (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Annual incidents of sexual victimization from the Uniform Crime Report (UCR) and the National Crime Victim Survey (NCVS), 2012; the National Inmate Survey-2, 2008–2009; and the National Survey of Youth in Custody 2008–2009: United States.

Note. We calculated the sex of victims in NCVS using the publicly available Victimization Analysis Tool http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=nvat. We generated a rough estimate of the number of annual incidents of sexual victimization in jails, prisons, and juvenile detention facilities by sex, using the 2008–2009 data, the most recent publicly available data on repeat incidents.50,54 (Repeat incidents were not reported in detail in 2011–2012.) To arrive at this, we multiplied a flow-adjusted number of detainees who reported at least one sexual victimization incident by the mean number of incidents of sexual victimization reported per victimized detainee. The flow-adjusted number of victims corrects for persons moving in and out of facilities during the 12-month sampling. The US Department of Justice Regulatory Impact Assessment of PREA55 provides a flow-adjusted prevalence estimate of sexual victimization. The NIS-2 and NSYC report on the number of incidents of victimization as a range; we used the middle of the range. NISVS findings are not included because data on number of incidents have not been made public.

aMen were excluded from the definition of rape.

Comparability is limited, as the inmate surveys include a much broader range of victimization, such as sex between staff and inmates that inmates report as “willing.” When guards and other staff engage in sexual activity with inmates in their care, it occurs in the context of an extreme power imbalance and is a criminal offense in all 50 states. We therefore find it worthy of inclusion. Moreover, more than half of both male and female prison and jail inmates who report staff sexual misconduct indicate that at least some of the sexual activity was “pressured”; more than one third indicate that some of it was accomplished with “force or threat of force.”50

We have presented these figures not to offer a precise overall estimate of sexual victimization in the United States but to suggest that relying solely on NCVS household surveys vastly underrecognizes sexual victimization incidents that occur among men. (Prevalence data from the NISVS serve as further evidence of the NCVS’s undercount of male and female victimization; Figure 1.)

We understand the reasons for using household surveys, and we acknowledge the complexities inherent in surveying vulnerable populations, which include not only the incarcerated but also homeless persons and those in care facilities, such as nursing homes. We underscore, however, that exclusive reliance on household methods may paint a misleading picture of sexual victimization in the United States by missing those at enormous risk. In addition to advocating greater awareness about such bias, we recommend the development of methods that would derive population estimates from the results of both household surveys and surveys of institutionalized individuals.

ADDITIONAL METHODOLOGICAL LIMITATIONS

We find it noteworthy that the newer NISVS and the BJS detainee surveys show less disparity between male and female reports of sexual victimization than does the longstanding crime survey, NCVS (Figures 1 and 2). In 2012, male victims experienced 38% of incidents, but the previous 5 years of NCVS data show even greater gender disparity. The percentage of rape and sexual assault incidents committed against males ranged from only 5% to 14% from 2007 to 2011.49 Because NCVS in an omnibus crime survey, rather than a survey focused specifically on sexual victimization, one would anticipate lower reporting overall. But what explains the marked gender disparity in reporting among these federal surveys?

Perhaps because NCVS is focused on crime, rather than on health or sexual victimization specifically, men are less likely to report unwanted sex (particularly with a female abuser) as criminal, thus leading to a greater gender disparity in the NCVS than in noncrime surveys. Additionally, the victim-sensitive survey methods used more recently in the NISVS and the BJS detainee surveys may be especially useful for eliciting male disclosure. For example, CDC researchers used graduated informed consent and frequent check-ins to build rapport and ensure participant comfort. BJS went to great lengths to reassure inmate and juvenile respondents about confidentiality, an important approach in the “snitching”-averse confinement context. The detainee surveys were also self-administered, which helps overcome disclosure resistance.

Both the NISVS and the BJS detainee surveys ask many frank, behaviorally specific questions, for example, “Did another inmate use physical force to make you give or receive oral sex or a blow job?”47(p41) and more numerous questions, strategies that generally increase reporting by acclimating respondents to the topic, desensitizing them (perhaps especially men), to the discomfort of disclosure.51 By contrast, the NCVS, an instrument meant to cover a broad range of crimes, contains only nonbehaviorally specific questions about sexual abuse. These (and perhaps still other) differences in survey methods may explain why the newer NISVS and BJS detainee data capture more male victimization than do federal crime data.

Crime and health surveys do not necessarily intend to measure the same events. But to the extent that the newer victim-sensitive methods increase the reporting of the types of sexual victimization experiences with which crime surveys ought to be concerned, such methods should be considered for the NCVS to increase the reporting of sexual crimes among women and men.

CONCLUSIONS

While recognizing and lamenting the threat that sexual victimization continues to pose for women and girls, we aim to bring into the fold the vast cohort of male victims who have been overlooked in research, media, and governmental responses. In so doing, we first argue that it is time to move past the male perpetrator and female victim paradigm. Overreliance on it stigmatizes men who are victimized,8 risks portraying women as victims,52 and discourages discussion of abuse that runs counter to the paradigm, such as same-sex abuse and female perpetration of sexual victimization.

Second, we note that to bring greater attention to the full spectrum of sexual victimization, definitions and categories of harm that federal agencies use should be revised to eliminate gendered and heterosexist bias. Specifically, the emphasis on the directionality of the sex act (i.e., the focus on victim penetration) should be abandoned. Such revisions in terminology and categorization of harms should aim to include sexual victimization regardless of the gender of victims and perpetrators. To better capture the forms of victimization with which federal agencies ought to be concerned, studies should use victim-sensitive survey methods that facilitate disclosure and may be especially prone to illicit male reporting.

Third, any comprehensive portrayal of sexual victimization in the United States must acknowledge the now extensively well-documented victimization of incarcerated persons to accurately reflect the experiences of large numbers of sexually victimized men. Because the United States disproportionately incarcerates Black, Hispanic, low-income, and mentally ill persons, accounting for the experience of the incarcerated population will help researchers and policymakers better understand the intersecting factors that lead to the sexual victimization of already marginalized groups. Homeless persons and other institutionalized individuals may be similarly vulnerable. To arrive at better estimates of sexual victimization, analytic approaches that combine data from households and nonhousehold populations are necessary.

Finally, a gender-conscious analysis of sexual victimization as it affects both women and men is needed and is not inconsistent with a gender-neutral approach to defining abuse.53 Indeed, masculinized dominance and feminized subordination can take place regardless of the biological sex or sexual orientation of the actors. We therefore advocate for the use of gender-conscious analyses that avoid regressive stereotyping, to which both women and men are detrimentally subject. This includes an understanding of how gender norms can affect the sexual victimization of all persons.53

Acknowledgments

Work on this article was supported, in part, by a grant from the Ford Foundation to the Williams Institute (grant 0130-0650).

The authors wish to thank Christina Kung, Tiffany Parnell, and Brad Sears.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not necessary, as we analyzed data in previously published reports.

References

- 1.Fitzpatrick J. The Use of International Human Rights Norms to Combat Violence Against Women. Human Rights of Women: National and International Perspectives. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crenshaw KW. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43(6):1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacKinnon CA. Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millett K. Sexual Politics. Garden City, NY: Doubleday; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The National Inmate Partner And Sexual Violence Survey. 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/NISVS_Report2010-a.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2012.

- 6.Copelon R. Surfacing gender: reengraving crimes against women in humanitarian law. In: Nicole Ann Dombrowski, ed. Women and War in the Twentieth Century: Enlisted With or Without Consent. New York, NY: Garland; 1990:245–266.

- 7.Kapur R. The Tragedy of Victimization Rhetoric: Resurrecting the Native Subject in International/PostColonial Feminist Legal Politics. London, UK: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scarce M. The Spectacle of Male Rape. Male on Male Rape: The Hidden Toll of Stigma and Shame. New York, NY: Insight Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9. US Department of Justice. Prisoners in 2012—advance counts. 2013. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p12ac.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2014.

- 10. US Department of Justice. Jail inmates at midyear 2012—statistical tables. 2013. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/jim12st.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2014.

- 11.Denov MS. The myth of innocence: sexual scripts and the recognition of child sexual abuse by female perpetrators. J Sex Res. 2003;40(3):303–314. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendel MP. The Male Survivor: The Impact of Sexual Abuse. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith BV. Uncomfortable places, close spaces: female correctional workers’ sexual interactions with men and boys in custody. UCLA Law Rev. 2012;59(6):1690–1745. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brownmiller S. Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelles RJ. The politics of research: the use, abuse, and misuse of social science data—the cases of intimate partner violence. Fam Court Rev. 2007;45(1):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutton DG, Nicholls TL. Gender paradigm in domestic violence research and theory: Part 1—The conflict of theory and data. Aggress Violent Behav. 2005;10(6):680–714. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller AM. Sexuality, violence against women, and human rights: women make demands and ladies get protection. Health Human Rights J. 2004;7(2):16–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gear S. Behind the bars of masculinity: male rape and homophobia in and about South African men’s prisons. Sexualities. 2007;10(2):209–217. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimmel MS. Masculinity as homophobia: fear, shame, and silence in the construction of gender identity. In: Gergen MM, Davis SN, editors. Toward a New Psychology of Gender. New York, NY: Routledge; 1997. pp. 223–224. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Struckman-Johnson C, Struckman-Johnson D. Acceptance of male rape myths among college men and women. Sex Roles. 1992;7(3/4):85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R et al. Revising the SES: a collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychol Women Q. 2007;31(4):357–370. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clay-Warner J, Burt CH. Rape reporting after reforms: have times really changed. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(2):150–176. doi: 10.1177/1077801204271566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss KG. Male sexual victimization: examining men’s experiences of rape and sexual assault. Men Masc. 2010;12(3):275–298. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lonsway KA, Fitzgerald LF. Rape myths: in review. Psychol Women Q. 1994;18(2):133–164. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stemple L, Qutb S. Just what part of prison rape do you find amusing? San Francisco Chronicle. 2002. Available at: http://www.sfgate.com/opinion/article/PRISONS-Selling-a-Soft-Drink-Surviving-Hard-2811952.php. Accessed April 10, 2014.

- 26.Wakelin A, Long KM. Effects of victim gender and sexuality on attributions of blame to rape victims. Sex Roles. 2003;49(9/10):477–487. [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Center for Victims of Crime. Male rape. 2008. Available at: http://www.nsvrc.org/publications/articles/male-rape. Accessed October 12, 2012.

- 28.Groth AN, Burgess AW. Male rape: offenders and victims. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(7):806–810. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.7.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. CBS. Male-stalking rapist puzzles experts. 2009. Available at: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/male-stalking-rapist-puzzles-experts. Accessed September 28, 2012.

- 30.Capers B. Real rape too. 2011. Available at: http://www.californialawreview.org/assets/pdfs/99-5/02-Capers.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2012.

- 31.Posner RA. Sex and Reason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mezey G, King M. The effects of sexual assault on men: a survey of 22 victims. Psychol Med. 1989;19(1):205–209. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700011168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck AJ, Cantor D, Hartge J, Smith T. Sexual victimization in juvenile facilities reported by youth, 2012. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/svjfry12.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2013.

- 34. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The National Inmate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010. Findings on victimization by sexual orientation. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_sofindings.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2013.

- 35. US Department of Justice. National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) Technical Specification. 2012. Available at: http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/nibrs_technical_specification_version_1.0_final_04-16-2012.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2014.

- 36. US Department of Justice. Crime in the United States: forcible rape. Available at: http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2012/crime-in-the-u.s.-2012/violent-crime/rape/rapemain.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2013.

- 37. US Department of Justice. Uniform Crime Reporting Handbook. 2004. Available at: http://www2.fbi.gov/ucr/handbook/ucrhandbook04.pdf. Accessed January 18, 2014.

- 38.Berger RJ, Neuman WL, Searles P. Impact of rape law reform: an aggregate analysis of police reports and arrests. Crim Justice Rev. 1994;19(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savage C. US to expand its definition of rape in statistics. 2012. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/07/us/politics/federal-crime-statistics-to-expand-rape-definition.html?_r=1&. Accessed September 28, 2012.

- 40. US Department of Justice. Attorney general Eric Holder announces revisions to the uniform crime report’s definition of rape. 2012. Available at: http://www.fbi.gov/news/pressrel/press-releases/attorney-general-eric-holder-announces-revisions-to-the-uniform-crime-reports-definition-of-rape. Accessed September 28, 2012.

- 41. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The National Inmate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: fact sheet. 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/NISVS_FactSheet-a.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2012.

- 42.Rabin RC. Nearly 1 in 5 women in US survey say they have been sexually assaulted. 2011. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/15/health/nearly 1-in-5-women-in-us-survey-report-sexual-assault.html?_r=1&scp=2&sq=centers%20for%20disease%20control%20and%20prevention%20rape&st=cse. Accessed September 28, 2012.

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence widespread in the US. 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2011/p1214_sexual_violence.html. Accessed December 17, 2013.

- 44.McMahon-Howard J. Does the controversy matter? Comparing the causal determinants of the adoption of controversial and noncontroversial rape law reforms. Law Soc Rev. 2011;45(2):401–434. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahn AS, Jackson J, Kully C, Badger K, Halvorsen J. Calling it rape: differences in experiences of women who do or do not label their sexual assault as rape. Psychol Women Q. 2003;27(3):233–242. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walmsley R. World Prison Population List. 9th ed. London, UK: International Center for Prison Studies; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck AJ, Berzofsky M, Caspar R, Krebs C. Sexual victimization in prisons and jails reported by inmates, 2011–12. 2013. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/svpjri1112.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48. The Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003. Pub. L. No. 108-79, 42 U.S.C. §§15601–15609.

- 49.Truman J, Langton L, Planty M. 2014. Criminal victimization, 2012. 2013. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv12.pdf. Accessed January 21,

- 50.Beck AJ, Harrison PM. Sexual victimization in prisons and jails reported by inmates, 2011–12. 2010. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/svpjri0809.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2014.

- 51.Sorenson SB, Stein JA, Siegel JM, Golding JM, Burnam MA. The prevalence of adult sexual assault: the Los Angeles Epidemiologic Catchment Area Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126(6):1141–1153. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stemple L. Human rights, sex, and gender: limits in theory and practice. Pace Law Rev. 2012;31(3):823–836. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stemple L. Male rape and human rights. Hastings Law J. 2009;60(605):628. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beck AJ, Harrison PM, Guerino P. Sexual victimization in juvenile facilities reported by youth. 2010. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/svjfry09.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2014.

- 55. US Department of Justice. Regulatory impact assessment for PREA final rule. 2012. Available at: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/programs/pdfs/prea_ria.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2014.