Abstract

Research shows that constraining aspects of male gender norms negatively influence both women’s and men’s health. Messaging that draws on norms of masculinity in health programming has been shown to improve both women’s and men’s health, but some types of public health messaging (e.g., Man Up Monday, a media campaign to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted infections) can reify harmful aspects of hegemonic masculinity that programs are working to change. We critically assess the deployment of hegemonic male norms in the Man Up Monday campaign. We draw on ethical paradigms in public health to challenge programs that reinforce harmful aspects of gender norms and suggest the use of gender-transformative interventions that challenge constraining masculine norms and have been shown to have a positive effect on health behaviors.

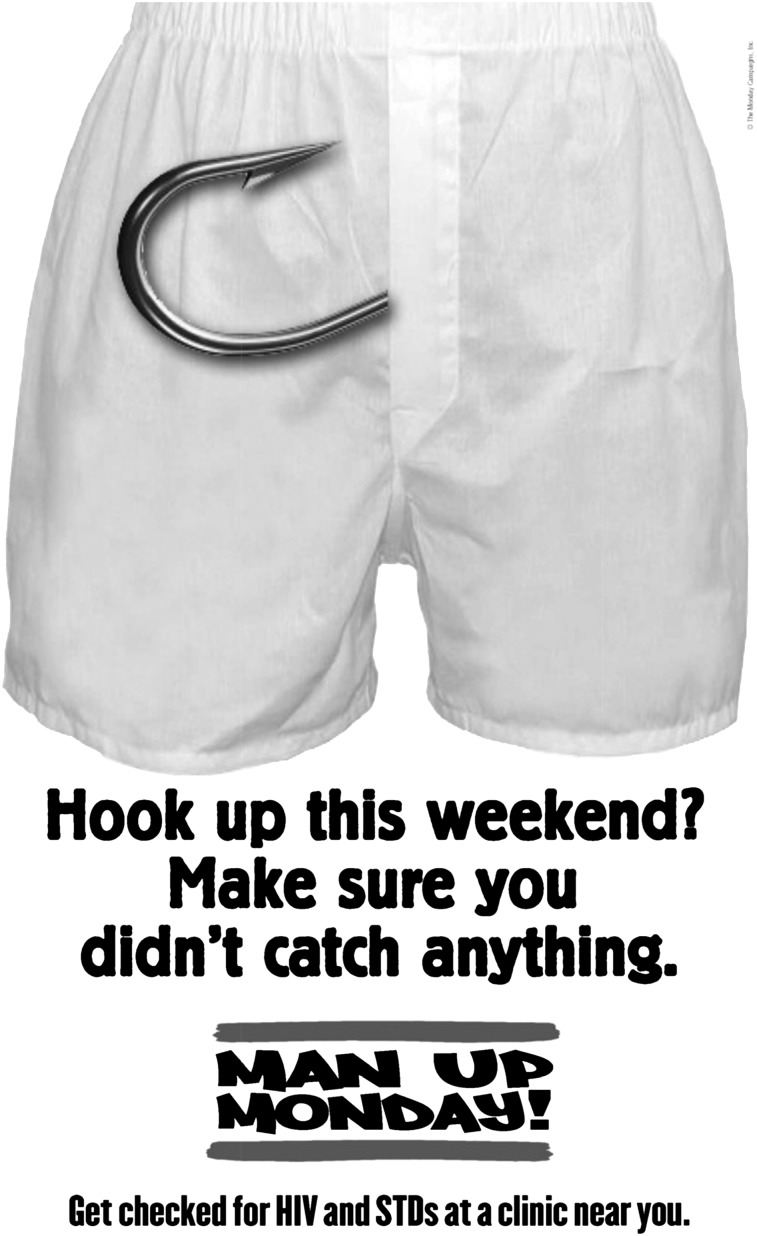

Unintended and harmful consequences can lurk behind even the most promising and innovative public health interventions.1,2 The Public Health Education and Health Promotion Section of the American Public Health Association (APHA) awarded the media campaign Man Up Monday first prize in the creative print category at the 2012 APHA Annual Meeting.3 This innovative print media campaign, which was implemented in southeastern Virginia in 2012, sought to increase the percentage of men tested for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) by leveraging community media campaigns that called for men to “man up” after weekend risk taking by attending clinics to get tested for STIs (Figure 1). In pilot testing, the program resulted in an impressive 200% increase in the number of men that tested for STIs.4

FIGURE 1—

Print marketing material for the Man Up Monday campaign.

At first glance, the campaign has used public health best practices. For example, Man Up Monday draws on the documented favorable conditions of Mondays for behavior change5 to facilitate a shift in men’s health-seeking behaviors. It also deploys language that is relevant to young men6 and uses savvy advertising to appeal to the target population by conveying the image that STI testing is hip. Man Up Monday advertisements include a photo of boxer shorts or condoms and have taglines such as, “If you hit it this weekend, hit the clinic Monday” (Figure 2). The ads ask men to “man up,” a colloquialism indicating the adoption of masculine ideals such as courage and being strong-willed.6 By suggesting that it is manly to get tested for STIs and linking this specific gender ideology to health behaviors, the program recognizes and deploys male gender norms to change men’s behaviors—an oft-recommended strategy for furthering health and well-being.7–9

FIGURE 2—

Print marketing material for the Man Up Monday campaign.

However, interventions using approaches that leverage gender norms require careful consideration as researchers have documented the detrimental effects of narrowly defined gender norms and gender inequality on the health of men, women, and children. We define gender norms as “those qualities of femaleness and maleness that develop as a result of socialization rather than biological predisposition.”10(p146) In most societies across the globe, men as a group enjoy social and institutional privileges over and above women as a group.11 However, masculine norms do not only lead to higher social status but they also come with a price for men’s health, often referred to as “costs of masculinity.”11 Paradoxically, to be perceived as masculine and thus to achieve the higher social status and power afforded to “real” men, men are pressured to and rewarded for adopting certain traits (e.g., being aggressive, virile with many sexual partners, unemotional, in control, adventurous, risk taking, dominant) that result in vulnerability to negative physical and mental health consequences.12–14 Furthermore, adoption of inequitable beliefs and adherence to traditional norms of masculinity have been found to be associated with violence,15–18 risky sexual behaviors,12,19,20 and sexual and intimate partner violence against women,20–22 which in turn negatively affect the health of men, women, and children.

Even though the Man Up Monday campaign leverages best practices, it is crucial to thoughtfully and constructively critique messaging strategies used in programs such as this one to advance and refine the development of future gender-related health interventions. Even well-intentioned, carefully designed programs can have unintended consequences and may need improvement. We argue for the importance of gender-transformative health interventions that “transform gender roles and promote more gender equitable relationships between men and women,”7(p4) rather than those that reinforce the norms of masculinity that have been shown to harm health. We start by reviewing the recent history of efforts to address gender norms in the name of improved health for both women and men; we then define some of the pitfalls and ethical implications of current approaches that deploy reinforcing instead of gender-transformative notions of manhood; we end by offering a path forward for public health interventions that seek to intervene on masculinities in the name of improved health.

EVOLVING PERSPECTIVES ON GENDER AND HEALTH

The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo spurred a global focus on women’s rights and gender equality and elaborated the links between women’s rights and sexual and reproductive health.23 Since the pivotal Cairo conference, public health practitioners and researchers have made substantial progress in embracing women’s rights and examining and intervening upon social constructions of gender when tackling health issues both globally and locally.24,25 Public health intervention strategies increasingly aim to empower women and transform gender structures and power dynamics that inhibit women’s autonomy and harm their health.26–28 Health promotion programs, as well as grassroots women’s movements, are empowering women to seek health care,29 be treated as equals in the health care system,30 have control over their own bodies,31 earn their own money,27 improve their educational status,32 secure their land and inheritance rights,33,34 increase their access to HIV testing and contraceptives,35–37 and improve their decision-making power in romantic and sexual relationships.38

Although a focus on gender equality after the Cairo conference motivated an emphasis on global heath programs targeting women and girls, research on women’s health and empowerment also identified narrow and constraining masculine norms as an important barrier to women’s and girls’ health and well-being.39–41 Further examination of gender relations led to growing recognition that men’s behaviors are also largely influenced by socially constructed gender norms, rather than motivated by traits that are biologically inherent in males.8,42–45 Gender norms, similar to other social norms, are influential in patterning individual behaviors partly because of the fact that nonadherence to norms is often punished by varying degrees of social exclusion. Too often, deviation from masculine ideals leads to violence against gay men and heterosexual men who are perceived to not neatly conform to the social definitions of maleness.46,47 Those men who do not outwardly adhere to the most dominant and highly valued aspects of manhood in contemporary terms may be victimized, stigmatized, or otherwise relegated to lower social status.14

As recognition of the importance of men’s gender norms grew, there was and continues to be an evolution in global and public health approaches that recognize, leverage, and seek to change particularly harmful aspects of gender norms. We examine and describe the continuum of gender-related approaches in the box on the next page. Initially, efforts were considered gender-neutral because they failed to account for the existence of differing gender norms and failed to address the differential social context of men and women.48 As research on gender and health developed, gender-sensitive approaches emerged as a best practice that resulted in a shift from gender-neutral to gender-sensitive health programs.48,49 For example, the first international public health treaty, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, includes language calling for gender-sensitive interventions.50,51 Large-scale organizations administering public health programs, such as the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the United Nations, also have adopted this approach and recommend (and in some cases require) integrating a gender-sensitive perspective into all health programming.52–54 Gender-sensitive programs recognize the role of gender in moderating program outcomes and modify program strategies to meet men’s and women’s different needs.55 For example, gender-neutral HIV prevention interventions were initially critiqued for not taking into account the fact that women face multiple and competing demands such as work, housing, child care, and family and thus experience unique challenges in prioritizing their health. As a result, gender-sensitive HIV prevention interventions were designed to recognize these gender-related constraints.55,56 However, as noted in the box on this page, the effects of these approaches may be limited because they generally intervene at the level of individuals or small groups and do not change the context in which women’s health choices are made.

Continuum of gender-related approaches to public health interventions.

| • Gender-damaging programs “reinforce damaging gender and sexual stereotypes,” especially those that reinforce stigma, vulnerabilities, or harmful behaviors. |

| • Gender-neutral programs do no harm, but are not targeted at either gender and “make no distinction between the needs of women and men.” These approaches often “fail to respond to the gender-specific needs of individuals.” |

| • Gender-sensitive programs “recognize and respond to the differential needs and constraints of individuals based on their gender.” But “they do little to change the larger contextual issues” and are “not sufficient to fundamentally alter the balance of power in gender relations.” |

| • Gender-transformative programs seek to “transform gender roles and create more gender-equitable relationships” between men and women. |

Source. Adapted and quoted from Geeta Rao Gupta’s plenary address at the XIII International AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa.48

Although the field of public health has focused over the past 2 decades on the ways in which gender norms influence health behaviors, several other industries have long profited from recognizing, leveraging, and reinforcing beliefs about aspirational signifiers of gender, thus shaping men’s and women’s health-related behaviors.13 The tobacco industry, for example, has spent decades carefully working to move smoking into a socially acceptable behavior for women to boost profits.57–59 Tobacco companies have also “sold” norms of femininity in their print media campaigns to directly appeal to adolescent girls sexually with products such as the chic Camel Number 960 and both subtle and overt changes in product packaging to promote gendered ideals.61 Additionally, appeals to rugged (e.g., Marlboro, Camel) and hip (e.g., Kool) images that reinforce hegemonic notions of masculinity have long been used to draw boys into tobacco addiction.44 By reinforcing the masculine–feminine dichotomy and associated ideals, marketers create a dynamic in which consumers perceive that they can (and should) literally buy into aspirational identities and lives. As with most ideals, very few individuals feel they measure up, which opens up possibilities for marketing and behavior change interventions.62

Acknowledgment of the power and sway of normative gender roles that are put forward by industry and marketing does little to change the existing system of gender norms and in fact works to reinforce it. In the case of public health interventions, many scholars have argued that gender-neutral and even gender-sensitive approaches are insufficient to permanently improve health outcomes associated with gender norms.8,9,63,64 Scientists and practitioners working in the areas of violence and sexual health have instead advocated that interventions should take a gender-transformative approach.7–9,65 These approaches attempt to change gender norms in ways that challenge constraining definitions of masculinity, foster gender equality, and democratize relationships between women and men, leading to positive health outcomes. In a recent systematic literature review, gender-transformative interventions that foster gender equality and reshape several key norms of masculinity associated with harmful health outcomes have been found to increase protective sexual behaviors, prevent partner violence, modify inequitable attitudes toward women, and reduce incidence of STI/HIV.66 We provide a more in-depth examination of gender-transformative programs in the final section of the article.

The field of public health has arrived at a point where gender norms are routinely acknowledged and sometimes intervened upon to improve health outcomes. However, the field has been less critical about the specific approaches used in gender-related public health programs. In the next 2 sections, we argue that public health efforts that reinforce adherence to dominant gender norms known to harm health, rather than challenge or transform them, have pragmatic and ethical implications that can hinder progress toward improving the public’s health.

PITFALLS OF REINFORCING HARMFUL GENDER NORMS

Although numerous cultural and social factors influence prevailing gender norms (e.g., education, family socialization, economic and occupational opportunity, institutional and public policies and practices), public health programs seeking to leverage norms must recognize that they too can be part of the creation and continuation of problematic notions of gender. Campaigns asking men to “man up,” or draw on other similar appeals to bolster masculinity, have the potential to invoke positive action (i.e., getting tested) from men who are hoping to be perceived as masculine. Unfortunately, they also have the potential to reinforce “hegemonic masculinity” (i.e., the most dominant norms of masculinity in a given era in a given time).67 Previous research has found that men who adhere to the norms of hegemonic masculinity have worse mental health68 and general well-being69 than do other men. Additionally, they are more likely to maintain high degrees of control over their female partners,70 engage in more sexual risk taking,20 avoid health care clinics,71 and enact more physical and sexual violence with their partners.30 Paradoxically, then, interventions that bolster masculinist notions of manhood (“Be a real man!”) have been definitively linked to the negative health outcomes that public health programs are attempting to ameliorate. As the primary message to encourage STI testing, the call to “man up” bolsters a narrow construction of manhood that is known to reinforce harmful heath outcomes.

Although “man up” is used as messaging in an intervention to encourage STI testing, it can also draw on existing colloquial calls to “be a real man” by taking on more sexual partners, standing up to perceived disrespect from others with violence, or not using a condom.11,12 By asking men to man up and get tested, campaigns such as this emphasize and support the notion that STI testing is required to achieve a masculine status. Because the same “man up” language has been used more broadly by men to encourage violent or sexually domineering behavior, the Man Up Monday campaign inadvertently lends support to these appeals. The campaign makes this link not only by telling men to man up and receive an STI test, but by including phrases such as “if you hit it” (referring to sex) and imagery (a bed) that evoke stereotypical aspects of male sexuality. The intervention then seeks to redefine the health behavior of interest (STI testing) as a positive, masculine behavior.

Using the continuum of health interventions established by Gupta, this type of effort can be considered a gender-damaging approach because it specifically exploits the rigidity of male gender norms.4,48 This reinforcement of hegemonic norms undercuts STI prevention efforts that promote respectful, communicative, and responsible sexual relationships.48 Although strengthening the existing system of gender norms has implications for all men, it has particularly important consequences for marginalized men. Consider the well-documented disparity in suicidal ideation among adolescent boys deemed gay by their peers.47 Regardless of their actual sexual orientation, the social processes that render abstinent, effeminate, gay, bisexual, transgender, or simply different adolescent boys as targets of harassment and social exclusion are part of the construction and policing of masculinity. Less blatant, but similarly destructive, are the construction and policing of maleness that hinder all men, but particularly low-income and racial/ethnic minority men, from achieving optimal health.13 Scholarship finds that minority men disproportionately pay the costs of masculinity that affect health because of the way structures of opportunity afford them fewer means to achieve hegemonic success.12 Hence, such men may rely more on adhering to norms of masculinities to achieve social status and thus, all too often, the health costs of masculinities fall on the their shoulders.12,72,73 Man Up Monday and similar gender-reinforcing interventions are not only echoing this social pressure to be masculine to achieve or maintain status, they are strengthening the pressure by lending the institutional weight of public health organizations.

ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS OF GENDER-REINFORCING INTERVENTIONS

On the basis of the current state of evidence that gender inequality and norms of masculinity are drivers of negative health outcomes, approaches that purposefully reinforce hegemonic norms may be considered unethical. Kass’s public health ethics framework recommends that researchers and program practitioners “fairly balance” the benefits and burdens of public health programs and ask if there are “alternative approaches.”74(p1780) The Society of Public Health Education75 and the Public Health Leadership Society76 both have codes of ethics that warn against interventions that have harmful effects on individuals or society. Interventions that reinforce the inequitable system of gender norms are predicated on individuals wanting to be perceived as adhering to narrowly originated norms of masculinity, but men’s efforts to adhere to such norms result in potentially harmful behaviors. Additionally, calls for public health as social justice require practitioners and researchers to examine and address existing structures of power, including gender inequalities.77

Although reinforcement of gender norms is pervasive throughout US society (e.g., marketing, media), public health professional ethics clearly require that we hold our programs and interventions to a higher standard. If public health interventions had no alternative approaches,74 gender-reinforcing approaches could be considered ethical to achieve a specific health outcome. However, there are alternatives: gender-transformative approaches. Because gender-transformative approaches do not rely on adherence to harmful gender norms and instead aim to challenge the inequitable system of gender norms, their implementation would minimize harms and burdens while producing similar desired health outcomes. Even more importantly, gender-transformative interventions address the gender and power structures at the root of a host of harmful behaviors and therefore can effect positive changes beyond the stated program goals. Programs can rarely eliminate all potential harms. However, within the evidence base, gender-transformative programs have been found to reduce inequitable attitudes toward women, rework the norms of masculinity that harm health, and promote positive health changes for both women and men.66

In the next section, we discuss how gender-transformative public health interventions have achieved much success by attempting to de-emphasize hegemonic ideals and transforming narrow conceptions of what it means to be a man, thus shifting gender relations in the direction of more equality between women and men.9,11,42,48,64,78,79

A PATH TOWARD GENDER EQUITY

Previous research has demonstrated the scarcity of sexual health programs for men in the United States and the need to use gender-transformative interventions to address the normative roots of men’s risky sexual behaviors.8 Although we commend efforts such as Man Up Monday for aiming to fill an important gap given the very real dearth of health interventions designed to reduce negative health outcomes among heterosexually active men, we are cautious about approaches—in the United States and elsewhere—that reinforce hegemonic norms to produce positive health outcomes.

Campaigns such as Man Up Monday could adopt various gender-transformative strategies to move away from the reinforcement of hegemonic masculinity and toward the promotion of a more gender-equitable masculinity. First, such campaigns could modify messaging strategy to focus less on manning up and more on questioning the characteristics of contemporary masculinity that prevent men from seeking health care services.12,13,80 Messaging, developed through pilot testing, could call on men to question the norm that men do not seek health care at all or that they wait unless their condition is dire. Campaigns could use places where men congregate (e.g., schools, workplaces, recreational facilities) as locations to disseminate information and facilitate conversations among men, offering opportunities to critically reflect about what it means to be a man, including examining the norms that lead men to not use condoms, have multiple partners, or take other sexual risks that can lead to STIs. By adopting these gender-transformative strategies, the campaign would provide a safe space in which men can actively recognize, challenge, and reconfigure gender norms in the presence of other men to improve health. As a result, men would not only potentially feel more comfortable seeking health care services—including STI testing—in the future, but also take preventive action to decrease the likelihood of contracting an STI.

Intervention developers aiming to adopt gender-transformative strategies can look to the emerging literature on evidence-based gender-transformative programs that have been implemented within the past decade. Stepping Stones, a cluster randomized control trial implemented in South Africa, demonstrated the effectiveness of a gender-transformative approach at changing sexual and violent behaviors in men.81,82 There are several additional examples of gender-transformative programming have been developed and implemented by leaders in the field of transforming male gender norms to promote health behaviors. One program, Program H, developed by Instituto Promundo in Brazil, uses a group educational format with young men to challenge male norms of violence and multiple partners within a safe environment facilitated by a male role model.64,78 This program has shown that men who participate in discussions that question existing male gender norms have improved health behaviors and outcomes.42,66 For example, one module of the Program H curriculum instructs the facilitator to lead a discussion on “the concept of prevention and the difficulties of ‘preventing’ given the myth that men are supposed to be ready to face any risk or to have sex at any time.”83(p55)

The facilitator uses interactive games to provide a safe space for the young male participants to discuss questions such as “What does it mean to be a man?” or “Why is it so difficult for some men to go to a urologist?”83(p55) These discussions call into question hegemonic gender norms and common myths related to male stereotypes. Previous research has shown that young men perceive their peers as less supportive of gender equality and nonviolent masculinities than they actually are.84 Gender-transformative interventions thus give participants greater awareness of gender-equitable attitudes in their community and help them to critically assess pressures to act more masculine. Not only has this program demonstrated improvements in men’s support for equitable gender norms, it has shown an increase in condom use and a decrease in incidence of STIs.42,78 Another example, One Man Can, developed and implemented by Sonke Gender Justice Network in South Africa, uses similar strategies in groups of men to foment support for challenging the strict nature of male gender norms. The program moves men toward greater support for gender equality to reduce the spread and impact of HIV and to reduce violence against both women and men.85,86

Gender-transformative intervention content can be delivered through a variety of strategies (e.g., group educational, mass media, couples counseling) and to any population (e.g., men’s groups, youths, community members, police, prisoners, women). Although still underused globally, efforts in developing countries have far outpaced public health programming in the United States and most other high-income countries with regard to gender-transformative programming. (For a recent review of gender-transformative interventions domestically and globally, see Dworkin et al.66) By building off of and adapting the successes of these previous gender-transformative approaches, and understanding the ethical and practical implications of gender-redefining interventions, the field of public health can better address the harmful effects of gender norms on health.

CONCLUSIONS

As gender expert Geeta Rao Gupta noted at the 2000 AIDS conference in Durban, South Africa,

To effectively address the intersection between HIV/AIDS and gender and sexuality requires that interventions should, at the very least, not reinforce damaging gender and sexual stereotypes… . Any gains achieved by such efforts in the short-term are unlikely to be sustainable.48(pp8–9)

Public health has an ethical obligation to carry out a careful assessment of the risks and benefits of existing programs according to the established evidence base. The currently available evidence on the harmful effects of adhering to hegemonic gender norms is too well established to ignore. We need not “man up” to the challenge; instead, the field must recognize that gender-transformative programs positively shape gender equality and health and call on researchers and practitioners to implement evidence-based programs and policies that work toward this goal.

Acknowledgments

P. J. Fleming received training support (T32 HD007168) and general support (R24 HD050924) from the Carolina Population Center, funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers at the Journal.

Note. The contents of this article do not necessarily represent the views of the funders or institutions.

Human Participant Protection

This research did not involve any primary data collection or contact with human participants.

References

- 1.Schwarz DF, Grisso JA, Miles C, Holmes JH, Sutton RL. An injury prevention program in an urban African-American community. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(5):675–680. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.5.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):216–221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.2012 PHEHP public health education materials contest award winners. Public Health Education and Health Promotion Newsletter. Fall 2012 Available at: http://www.apha.org/NR/rdonlyres/F895A66A-2919-4EDF-AC6F-B8384539EA6F/0/EditedPHEHPDraft_1.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Prevention Information Network. New Man Up Monday Campaign doubles STD testing of young men in Virginia trial by Planned Parenthood. 2012 Available at: http://www.cdcnpin.org/scripts/display/NewsDisplay.asp?NewsNbr=60626. Accessed May 20, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fry J, Neff R. Healthy Monday: Two Literature Reviews. Center for a Livable Future. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knight R, Shoveller JA, Oliffe JL, Gilbert M, Frank B, Ogilvie G. Masculinities, “guy talk” and “manning up”: a discourse analysis of how young men talk about sexual health. Sociol Health Illn. 2012;34(8):1246–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M. Engaging Men and Boys in Changing Gender-Based Inequity in Health: Evidence From Programme Interventions. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, Promundo; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dworkin SL, Fullilove RE, Peacock D. Are HIV/AIDS prevention interventions for heterosexually active men in the United States gender-specific? Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):981–984. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunkle KL, Jewkes R. Effective HIV prevention requires gender-transformative work with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(3):173–174. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.024950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boles JK, Hoeveler DL. Historical Dictionary of Feminism. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messner MA. Politics of Masculinities: Men in Movements. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(10):1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams DR. The health of men: structured inequalities and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):724–731. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connell RW. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker G. Dying to Be Men: Youth, Masculinity and Social Exclusion. New York, NY: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourgois P. In search of masculinity: violence, respect, and sexuality among Puerto Rican crack dealers in East Harlem. Br J Criminol. 1996;36(3):412–427. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong L. Toward a transformed approach to prevention: breaking the link between masculinity and violence. J Am Coll Health. 2000;48(6):269–279. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimmel MS, Mahler M. Adolescent masculinity, homophobia, and violence—random school shootings, 1982–2001. Am Behav Sci. 2003;46(10):1439–1458. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schensul SL, Nastasi BK, Verma RK. Community-based research in India: a case example of international and transdisciplinary collaboration. Am J Community Psychol. 2006;38(1–2):95–111. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santana MC, Raj A, Decker MR, La Marche A, Silverman JG. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. J Urban Health. 2006;83(4):575–585. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore TM, Stuart GL. A review of the literature on masculinity and partner violence. Psychol Men Masc. 2005;6(1):46–61. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haj-Yahia M. Can people’s patriarchal ideology predict their beliefs about wife abuse? The case of Jordanian men. J Community Psychol. 2005;33(5):545–567. [Google Scholar]

- 23. United Nations. Report of the International Conference on Population and Development. Paper presented at: International Conference on Population and Development; September 5–13, 1994; Cairo, Egypt. [PubMed]

- 24.Rosenfield AG. After Cairo: women’s reproductive and sexual health, rights, and empowerment. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1838–1840. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roseman MJ, Reichenbach L. International Conference on Population and Development at 15 years: achieving sexual and reproductive health and rights for all? Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):403–406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vyas S, Watts C. How does economic empowerment affect women’s risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published evidence. J Int Dev. 2009;21(5):577–602. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JC, Watts CH, Hargreaves JR et al. Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women’s empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1794–1802. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.095521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gollub EL. The female condom: tool for women’s empowerment. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(9):1377–1381. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.9.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manderson L, Mark T. Empowering women: participatory approaches in women’s health and development projects. Health Care Women Int. 1997;18(1):17–30. doi: 10.1080/07399339709516256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Currie D, Wiesenberg S. Promoting women’s health-seeking behavior: research and the empowerment of women. Health Care Women Int. 2003;24(10):880–899. doi: 10.1080/07399330390244257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoen J. Choice and Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and Welfare. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tembon M, Fort F. Girls’ Education in the 21st Century: Gender Equality, Empowerment, and Economic Growth. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grabe S. Promoting gender equality: the role of ideology, power, and control in the link between land ownership and violence in Nicaragua. Anal Soc Issues Public Policy. 2010;10(1):146–170. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu T, Zwicker L, Kwena Z, Bukusi E, Mwaura-Muiru E, Dworkin SL. Assessing barriers and facilitators of implementing an integrated HIV prevention and property rights program in western Kenya. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25(2):151–163. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez CA, Hernandez M, Faigeles B. Sex in the New World: an empowerment model for HIV prevention in Latina immigrant women. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26(2):200–212. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shrestha S. Increasing contraceptive acceptance through empowerment of female community health volunteers in rural Nepal. J Health Popul Nutr. 2002;20(2):156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pronyk PM, Kim JC, Abramsky T et al. A combined microfinance and training intervention can reduce HIV risk behaviour in young female participants. AIDS. 2008;22(13):1659–1665. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328307a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sterk CE, Theall KP, Elifson KW, Kidder D. HIV risk reduction among African-American women who inject drugs: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(1):73–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1022565524508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajunirwe F, Muzoora M. Barriers to the implementation of programs for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a cross-sectional survey in rural and urban Uganda. AIDS Res Ther. 2005;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seeley J, Grellier R, Barnett T. Gender and HIV/AIDS impact mitigation in sub-Saharan Africa—recognising the constraints. SAHARA J. 2004;1(2):87–98. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2004.9724831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M, Olukoya A, Santos C. Questioning gender norms with men to improve health outcomes: evidence of impact. Glob Public Health. 2010;5(5):539–553. doi: 10.1080/17441690902942464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrow M, Barraclough S. Gender equity and tobacco control: bringing masculinity into focus. Glob Health Promot. 2010;17(1 suppl):21–28. doi: 10.1177/1757975909358349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ng N, Weinehall L, Ohman A. “If I don’t smoke, I’m not a real man”—Indonesian teenage boys’ views about smoking. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(6):794–804. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pachankis JE, Westmaas JL, Dougherty LR. The influence of sexual orientation and masculinity on young men’s tobacco smoking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(2):142–152. doi: 10.1037/a0022917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taywaditep KJ. Marginalization among the marginalized: gay men’s anti-effeminacy attitudes. J Homosex. 2001;42(1):1–28. doi: 10.1300/j082v42n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorais M, Lajeunesse SL. Dead Boys Can’t Dance: Sexual Orientation, Masculinity, and Suicide. Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen’s University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gupta GR. HIV/AIDS: the what, the why and the how. Paper presented at: XIII International AIDS Conference; July 12, 2000; Durban, South Africa.

- 49.Bottorff JL, Haines-Saah R, Oliffe JL, Sarbit G. Gender influences in tobacco use and cessation interventions. Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47(1):55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greaves L, Tungohan E. Engendering tobacco control: using an international public health treaty to reduce smoking and empower women. Tob Control. 2007;16(3):148–150. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.016337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Regueira G, Suarez-Lugo N, Jakimczuk S. Tobacco control strategies from a gender perspective in Latin America [in Spanish] Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(suppl 2):S315–S320. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ravindran TK, Kelkar-Khambete A. Gender mainstreaming in health: looking back, looking forward. Glob Public Health. 2008;3(suppl 1):121–142. doi: 10.1080/17441690801900761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.US Agency for International Development. Guide to gender integration and analysis: additional help for ADS chapters 201 and 203. Available at: http://transition.usaid.gov/policy/ads/200/201sab.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2013.

- 54.United Nations Development Programme. Taking Gender Equality Seriously: Making Progress, Meeting New Challenges. New York, NY: Bureau for Development Policy, Gender Unit; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ehrhardt AA, Exner TM, Hoffman S et al. HIV/STD risk and sexual strategies among women family planning clients in New York: Project FIO. AIDS Behav. 2002;6(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ehrhardt AA, Exner TM, Hoffman S et al. A gender-specific HIV/STD risk reduction intervention for women in a health care setting: short- and long-term results of a randomized clinical trial. AIDS Care. 2002;14(2):147–161. doi: 10.1080/09540120220104677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.San Francisco Lesbian and Gay History Project. “She even chewed tobacco”: a pictorial narrative of passing women in America. In: Duberman MB, Vicinus M, Chauncey G, editors. Hidden From History: Reclaiming the Gay & Lesbian Past. New York, NY: New American Library; 1989. pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee K, Carpenter C, Challa C, Lee S, Connolly GN, Koh HK. The strategic targeting of females by transnational tobacco companies in South Korea following trade liberalization. Global Health. 2009;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson RG, Barry M, Bloch M et al. Report of the Tobacco Policy Research Group on marketing and promotions targeted at African Americans, Latinos, and women. Tob Control. 1992;1(suppl):S24–S30. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pierce JP, Messer K, James LE et al. Camel No. 9 cigarette-marketing campaign targeted young teenage girls. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):619–626. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. Designing cigarettes for women: new findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction. 2005;100(6):837–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dworkin SL, Wachs FL. Body Panic: Gender, Health, and the Selling of Fitness. New York, NY: NYU Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gupta GR. How men’s power over women fuels the HIV epidemic. BMJ. 2002;324(7331):183–184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7331.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Verma R, Weiss E. Addressing gender dynamics and engaging men in HIV programs: lessons learned from horizons research. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(2):282–292. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greig A, Peacock D, Jewkes R, Msimang S. Gender and AIDS: time to act. AIDS. 2008;22(suppl 2):S35–S43. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327435.28538.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dworkin SL, Treves-Kagan S, Lippman SA. Gender-transformative interventions to reduce HIV risks and violence with heterosexually-active men: a review of the global evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2845–2863. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Connell RW. Gender and Power. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sharpe MJ, Heppner PP. Gender role, gender-role conflict, and psychological well-being in men. Couns Psychol. 1991;38(3):323–330. [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Neil JM. Summarizing 25 years of research on men’s gender role conflict using the Gender Role Conflict Scale. Couns Psychol. 2008;36(3):358–445. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mahalik JR, Talmadge WT, Locke BD, Scott RP. Using the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory to work with men in a clinical setting. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61(6):661–674. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Falnes EF, Moland KM, Tylleskär T, de Paoli MM, Msuya SE, Engebretsen IM. “It is her responsibility’’: partner involvement in prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV programmes, northern Tanzania. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:21. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sabo D, Gordon F. Masculinity, health, and illness. In: Sabo D, Gordon DF, editors. Men’s Health and Illness: Gender, Power, and the Body. New York, NY: Sage; 1995. pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen CJ. The Boundaries of Blackness: AIDS and the Breakdown of Black Politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kass NE. An ethics framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1776–1782. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.National Commission for Health Education Credentialing. Health Education Code of Ethics. Available at: http://www.nchec.org/credentialing/ethics. Accessed March 29, 2013.

- 76.Thomas JC, Sage M, Dillenberg J, Guillory VJ. A code of ethics for public health. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(7):1057–1059. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.7.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beauchamp DE. Public health as social justice. Inquiry. 1976;13(1):3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pulerwitz J, Barker G, Segundo M, Nascimento M. Promoting more gender-equitable norms and behaviors among young men as an HIV/AIDS prevention strategy. 2002. Population Council, Washington, DC. Available at: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/horizons/brgendernorms.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2013.

- 79.Barker G, Ricardo C. Young Men and the Construction of Masculinity in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for HIV/AIDS, Conflict, and Violence. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(6):616–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J et al. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jewkes R, Wood K, Duvvury N. “I woke up after I joined Stepping Stones”: meanings of an HIV behavioural intervention in rural South African young people’s lives. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(6):1074–1084. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Instituto Promundo, Comunicação em Sexualidade, Programa de Apoio ao Pai, Salud y Género. Project H: working with young men series. 2002 Available at: http://www.promundo.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/Introd-Sexuality-Rep-Health.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fleming PJ, Andes KL, DiClemente RJ. “But I’m not like that”: young men’s navigation of normative masculinities in a marginalized urban community in Paraguay. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(6):652–666. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.779027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dworkin SL, Hatcher AM, Colvin C, Peacock D. Impact of a gender-transformative HIV and antiviolence program on gender ideologies and masculinities in two rural, South African communities. Men Masc. 2013;16(2):181–202. doi: 10.1177/1097184X12469878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van den Berg W, Hendricks L, Hatcher A, Peacock D, Godana P, Dworkin S. “One Man Can”: shifts in fatherhood beliefs and parenting practices following a gender-transformative programme in Eastern Cape, South Africa. Gend Dev. 2013;21(1):111–125. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2013.769775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]