Summary

The mucosal epithelium consists of polarized cells with distinct apical and basolateral membranes that serve as functional and physical barriers to the organisms’ exterior. The apical surface of the epithelium constitutes the first point of contact between mucosal pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and their host. We observed that binding of P. aeruginosa aggregates to the apical surface of polarized cells leads to the striking formation of an actin-rich membrane protrusion with ‘inverted’ polarity, containing basolateral lipids and membrane components. Such protrusions were associated with a spatially localized host immune response to P. aeruginosa aggregates that required bacterial flagella and a Type III secretion system apparatus. Host protrusions form de novo underneath bacterial aggregates and involve the apical recruitment of a Par3/Par6α/aPKC/Rac1 signaling module for a robust, spatially localized host NFκB response. Our data reveal an unanticipated role for spatio-temporal epithelial polarity changes in the activation of innate immune responses.

Introduction

The mucosal barrier, composed of adherent sheets of polarized epithelial cells with distinct apical and basolateral membranes that are connected by tight junctions (TJ) and adherens junctions (AJ), is one of the most fundamental components of the innate immune system. Initiation and maintenance of the polarized epithelium requires the spatial and temporal orchestration of a large network of proteins and lipids. Apical-basolateral polarity is initiated by the formation of primordial AJs that lack TJ components, while cadherins extending from adjacent cells interact to create homophilic intercellular adhesions. Subsequent Rho family GTPase activation leads to cytoskeletal rearrangements, resulting in the formation of mature TJs and AJs. In addition, cell polarity and junction integrity is regulated by three different apical- and basolateral-specific polarity complexes, including the apical Par complex comprised of Par3, Par6, aPKC. The asymmetric distribution of phosphatidylinositol phosphates (PIPs) also contributes to cell polarity, with PI-(4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) enriched in the apical surface and PI-(3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) localized to the basolateral surface (Rodriguez-Boulan and Macara, 2014).

Epithelial cell polarity plays a critical role in defense against microbial pathogens, including the often lethal opportunistic Gram-negative bacterium P. aeruginosa. When the epithelial barrier and the host immune system are intact, P. aeruginosa is unable to efficiently colonize the mucosal epithelium and cause disease. However, in the setting of injured or incompletely polarized epithelium, P. aeruginosa can initiate colonization and unleash its arsenal of potent virulence factors, which include the type III secretion system (T3SS) and its secreted effectors (Engel and Balachandran, 2009). This simple paradigm explains why P. aeruginosa is a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections, including ventilator-associated pneumonia, skin infections in burn patients or at the site of surgical incisions, and catheter-related infections (Mandell et al., 2010). P. aeruginosa is also a cause of chronic lung infections and ultimately death in patients with Cystic Fibrosis (Mandell et al., 2010). The molecular mechanisms and signal transduction pathways that connect pathogen sensing to the innate immune response in epithelial cells, however, remains incompletely understood (Artis, 2008; Ryu et al., 2010).

We have previously used P. aeruginosa infection of filter-grown epithelial cells to model host-pathogen interactions at the mucosal barrier (Bucior et al., 2010; Bucior et al., 2012; Kazmierczak et al., 2001). When grown for several days on semi-porous filters (Transwells), Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells form well-polarized, confluent monolayers with distinct apical and basolateral surfaces (Mostov, 1995). Notably, the degree of cell polarity negatively correlates with the final outcome of P. aeruginosa infection (Kazmierczak et al., 2001).

When P. aeruginosa is added to the apical surface of polarized epithelial cells, cell-associated bacterial aggregates are formed from free-swimming individual bacteria within minutes, often near cell-cell junctions (Lepanto et al., 2011). The binding of bacterial aggregates, but not individual bacteria, is associated with the transformation of a small patch of apical membrane into one with basolateral characteristics within 30 to 60 minutes of infection (Kierbel et al., 2007), prior to translocation of the type III secreted effectors and associated cytotoxicity (Balachandran et al., 2007; Soong et al., 2008). This spatial and temporal cortical domain transformation involves the production of a host membrane protrusion that is enriched for phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), its normally basolateral lipid product PIP3, actin, and several basolateral proteins. Importantly, TJs are not disrupted during the initial stages of protrusion formation, suggesting that protrusions result from localized rearrangement of the apical membrane rather than overt loss of cell polarity (Kierbel et al., 2007). How such remarkable polarity rearrangement can occur in an otherwise stable epithelium remains an unanswered question. Furthermore, the consequences of protrusion formation for both host and pathogen have not yet been examined. Here, we have elucidated the molecular regulation and function of these membrane events, including the critical host and pathogen factors required for their formation.

Results

PIP3-rich protrusions are formed de novo at the site of bacterial aggregate binding

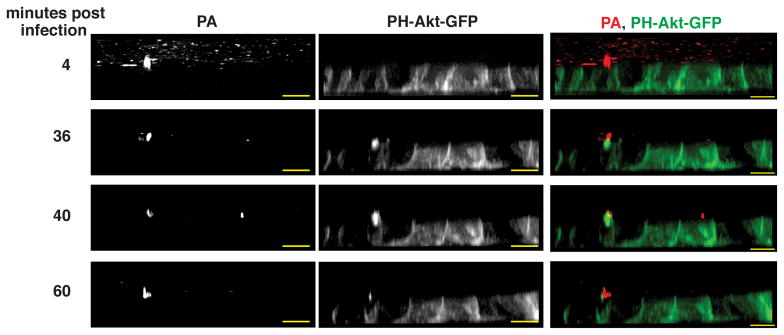

To investigate whether protrusions are formed in response to bacterial aggregate formation, we analyzed the dynamics of protrusion formation using time lapse spinning-disk confocal microscopy of filter-grown MDCK cells stably expressing PH-Akt-GFP, a probe for the normally basolateral lipid PIP3 (Watton and Downward, 1999) that robustly localizes to aggregate-associated protrusions (Kierbel et al., 2007). P. aeruginosa (strain PAK) expressing mCherry was added to the apical surface of MDCK monolayers and confocal optical stacks were acquired. Within 30 minutes, PIP3-rich protrusions rapidly formed de novo at the binding site of a bacterial aggregate and subsequently disappeared by 60 minutes (Figure 1, Movie S1). Thus, protrusions are dynamic structures that can be formed de novo on the apical surface of polarized cells in response to binding of bacterial aggregates.

Figure 1. PIP3-rich protrusions are formed de novo at the site of bacterial aggregate binding on the apical surface of polarized epithelial cells.

Selected XZ frames from time-lapse spinning disk confocal images of MDCK cells expressing PH-Akt-GFP (green, a marker for PIP3) infected with PAK-mCherry (red) (see also Movie S1). At 4 min, a bacterial aggregate bound to the apical surface is detectable. Many non-adherent individual bacteria are also observed. At 36 min post-infection, a PIP3-rich protrusion forms underneath the bacterial aggregate and is less intense at 60 min post-infection. Scale bars, 10 μm. See also Movie S1.

Bacterial flagella and the T3SS are required for a localized host innate immune response

P. aeruginosa binding to epithelia has been shown to activate NFκB, a central regulator of the innate immune response (DiMango et al., 1998; Lavoie et al., 2011; Mijares et al., 2011; Sadikot et al., 2006; Schroeder et al., 2002), though the mechanism that connects P. aeruginosa binding to NFκB activation remains poorly understood (Hybiske et al., 2004). Thus, we examined whether aggregate binding and protrusion formation are involved in a spatially localized host response to bacteria.

We first determined whether the binding of P. aeruginosa aggregates was associated with NFκB activation, as assessed by nuclear translocation of the NFκB subunit p65. Immunofluorescence staining of p65 revealed a strong nuclear signal in epithelial cells underneath or adjacent to bacterial aggregates, in contrast to only a very weak nuclear signal in most non-adjacent cells (Figure 2A, left panel; Movie S2). We defined NFκB activation as a nuclear:cytoplasmic p65 ratio of ≥1 (see Supplemental Methods). Notably, the vast majority of bacterial aggregates (67%), but no adherent single bacteria (0/24), were associated with NFκB activation in underlying epithelial cells (Figure S1). Uninfected cells also did not exhibit NFκB activation (Figure S1). We further determined that actin-rich protrusions and local NFκB activation occur at the site of bacterial aggregate binding in 16HBE14o- cells (a human airway epithelial cell line) (Figure S2). These data suggest that localized protrusion formation and NFκB activation may occur as a host response to bacterial aggregation on the apical surface.

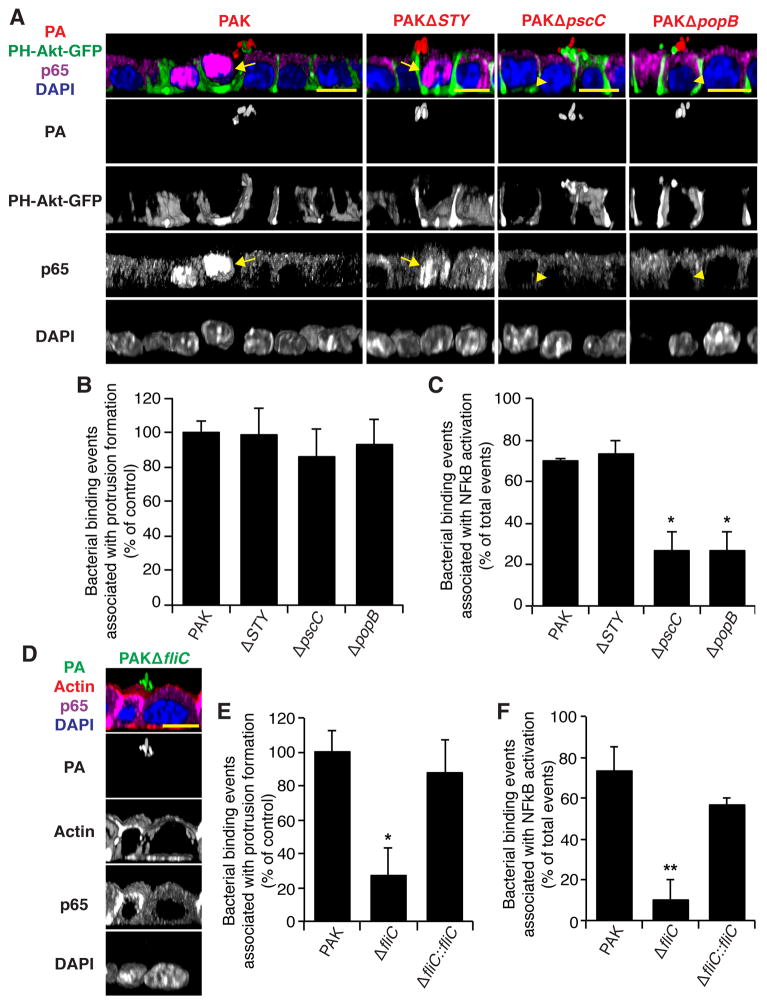

Figure 2. Bacterial factors required for aggregate-associated protrusion formation and NFκB activation.

(a) 3-D reconstruction, XZ view, of MDCK cells expressing PH-Akt-GFP infected with PAK or isogenic T3SS mutants expressing mCherry (red) for 30 min. Cells were fixed and stained with p65 antibody (NFκB, purple) and DAPI (nucleus, blue). Arrows indicate increased nuclear p65 staining in cells underneath or adjacent to bacterial aggregates, arrowheads indicate cells that show no change. (b, c) Bacterial binding events associated with protrusion formation (b) or NFκB activation (c) by aggregates (≥10 bacteria) of PAK or isogenic T3SS mutants (n = 3). Protrusion formation was measured by PIP3 as judged by PH-Akt-GFP recruitment. (d) 3-D reconstruction, XZ view, of MDCK cells infected with PAKΔfliC expressing GFP (green) for 30 min. Cells were fixed and stained with p65 antibody (NFκB, purple), phalloidin (actin, red), and DAPI (nucleus, blue). (d, e) Bacterial binding events associated with protrusion formation (d) or NFκB activation (e) by aggregates (≥10 bacteria) of PAK or isogenic mutants lacking flagellin (n = 3). Protrusion formation was measured by actin recruitment as judged by fluorescent phalloidin staining. Scale bars, 10 μm. Data are mean ± SEM. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 compared to PAK control. See also Figures S1, S2, Movie S2, and Statistics in Supplemental Data.

We next tested whether key virulence factors of P. aeruginosa, specifically flagella and the T3SS, were involved in protrusion formation and localized NFκB activation. To evaluate protrusion formation, bacterial aggregates and the underlying MDCK cells were imaged, and recruitment of cortical actin or PIP3 to the protrusion was analyzed in 3-D reconstructions using a well-defined set of criteria that minimized observer-to-observer variation (see Supplemental Methods). P. aeruginosa flagellin is known to activate NFκB both through TLR5 and through intracellular cytosolic sensors (Lavoie et al., 2011). The mutant PAKΔfliC, which fails to produce flagellin, shows ~50% reduction in binding to the apical surface of polarized MDCK cells (Bucior et al., 2012). Despite less efficient binding by PAKΔfliC, this mutant still formed aggregates on the apical surface of cells, albeit at a reduced frequency (C. Tran and J. Engel, unpublished results). We found that protrusion formation associated with bacterial aggregates, as assessed by actin recruitment, was decreased by 75% in PAKΔfliC (Figure 2E). Protrusion formation was restored in the complemented mutant (Figure 2E). Strikingly, NFκB activation was also reduced in cells infected with PAKΔfliC and restored in the complemented mutant (Figures 2D, 2F). Our results suggest that flagella, in addition to their role in adhesion, are necessary for both protrusion formation and localized NFκB activation.

We next focused on the T3SS, which is necessary for virulence in both in vitro and in vivo models of infection and is associated with poor outcome in human infections (Engel and Balachandran, 2009). PAK encodes and expresses three T3SS effectors: ExoS, ExoT, and ExoY (Ha and Jin, 2001). A strain lacking all known T3SS effectors, PAKΔSTY, formed aggregates, induced protrusions (Figure 2B), and stimulated robust, localized NFκB activation (Figures 2A, second panel; 2C), suggesting that the T3SS effectors are not involved in these processes. Aggregates and protrusions could be observed in host cells infected with PAKΔpscC (which lacks the T3SS needle apparatus and pore-forming translocon) or PAKΔpopB (which has an intact T3SS needle apparatus but lacks the translocon), albeit at a slightly reduced level (Figure 2B and C. Tran and J. Engel, unpublished observations). Remarkably, both PAKΔpscC and PAKΔpopB were significantly deficient in inducing NFκB activation (Figures 2A, 2C). Thus, our data suggest that P. aeruginosa aggregation and protrusion formation on the epithelium may both be necessary, but are not sufficient, for NFκB activation. Furthermore, a functional needle apparatus and translocon, but not the effectors, are required for local activation of the innate immune response.

The Par complex, Rac1, and AJ proteins are recruited to protrusions

We next qualitatively and quantitatively assayed potential host factors that are recruited to protrusions, with the hypothesis that components that are recruited to protrusions may also be necessary for activation of the NFκB response. The dramatic rearrangement of membrane composition in protrusions could involve polarity-regulating components such as the Par complex. The Par6/Cdc42/aPKC complex, together with Par3, has been implicated in the establishment and maintenance of cell polarity and is normally localized at TJs (Rodriguez-Boulan and Macara, 2014). We observed robust recruitment of Par3 and aPKC coincident with F-actin to protrusions (Figures 3A, arrows; 3C, S3A). Notably, the ‘Par’ complexes may exist in different subtypes, with basolateral Rac1-Par6α potentially substituting for the apical Cdc42-Par6β complex (Macara, 2004). Accordingly, exogenously expressed GFP-Par6α and GFP-Rac1 (Figures 3A, 3C, S3A) and endogenous Rac1 (Figure S3A), which are normally basolaterally located, were all strongly enriched in protrusions. Our efforts to analyze the recruitment of Cdc42 and RhoA were complicated by the largely cytoplasmic localization of these proteins, even when ectopically expressed. Thus, while both of these proteins were present within the protrusion, it was not clear if they were specifically enriched in the protrusion (data not shown). Nonetheless, these data suggest that a Par6α/Rac1/aPKC/Par3 module is recruited to the protrusion.

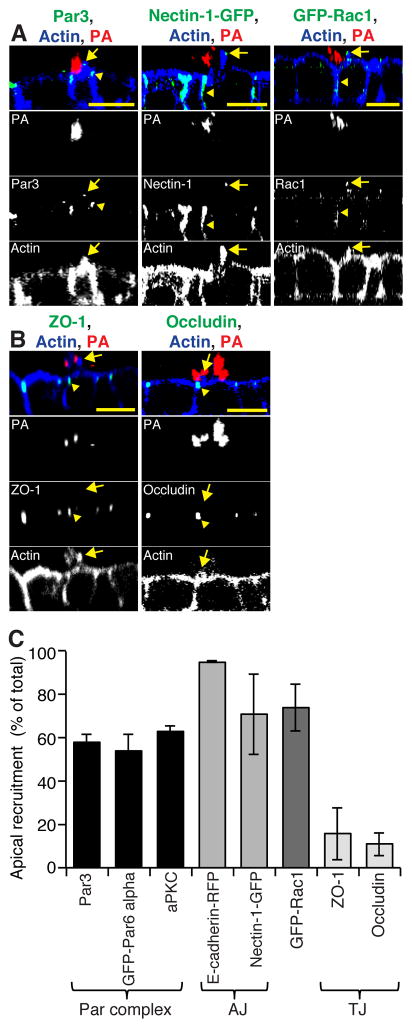

Figure 3. Par3, AJ proteins, and Rac1 are recruited to protrusions.

(a, b) Confocal XZ scans of MDCK monolayers infected with PAK-mCherry for 30 min. Samples were stained with fluorescent phalloidin (actin, blue) and immunostained for various proteins (Par3, ZO-1, occludin) to examine recruitment to protrusions. For some experiments, MDCK cells stably expressing fluorescent protein fusions (GFP-Par6α, GFP-Rac1, Nectin-1-GFP, E-cadherin-RFP) were used. Arrowheads indicate proteins at their expected localization; arrows indicate the location of the protrusion. (c) Quantification of host protein recruitment to protrusions as described in Supplemental Methods (n ≥ 2 independent experiments). The different classes of protein function are indicated. Scale bars, 10 μm. Data are mean ± SEM. See also Figures S3A and S4.

Par3 is a multi-PDZ domain-containing protein that is recruited to cell-cell junctions through multiple mechanisms that include interactions with both AJ and TJ proteins (Takekuni et al., 2003). We examined whether AJ or TJ proteins were similarly associated with the aggregate-induced protrusion. Strikingly, both the prototypical AJ protein E-cadherin and the Par3-interacting dual AJ/TJ adhesion protein Nectin-1 were enriched in protrusions (Figures 3A, 3C), whereas no other TJ proteins examined, including ZO-1 and occludin, were present (Figures 3B, 3C). In other systems, Nectin-1 initially localizes to developing cell-cell contacts before redistributing to TJs once contacts mature (Takekuni et al., 2003). Our data indicate that protrusions contain characteristics of rudimentary types of cell-cell contacts, including polarity and AJ proteins, but largely lack TJ proteins. These results suggest that bacterial aggregate detection may mimic the early phases of a nascent cell-cell contact.

PI3K and Rac1 are required for protrusion formation

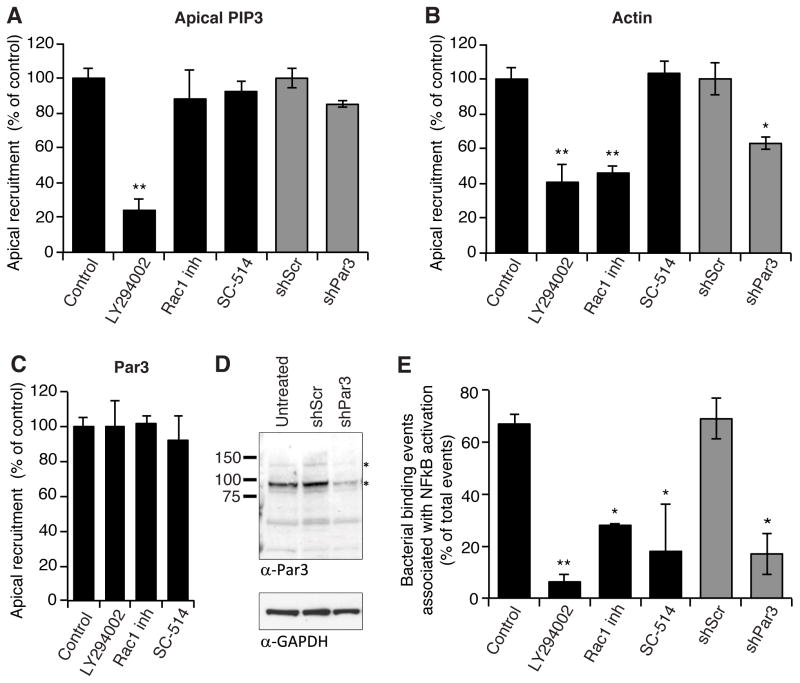

We tested the necessity and potential hierarchy of proteins recruited to protrusions, assessing the effect of chemical inhibitors or shRNA-mediated depletion on the recruitment of two robust markers of protrusions: PIP3 and F-actin (see Supplemental Methods). None of the inhibitors or RNAi perturbed monolayer integrity (data not shown). Inhibition of PI3K by LY294002 significantly decreased aggregate-induced PIP3 accumulation on the apical membrane (Figure 4A), confirming previous observations (Kierbel et al., 2007) and validating our quantification methodologies. PI3K inhibition similarly decreased F-actin recruitment to the protrusion (Figure 4B), consistent with a function for PIP3 in regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (Czech and Corvera, 1999). In accordance with its recruitment to protrusions, chemical inhibition of Rac1 (Rac1 inhibitor) decreased F-actin recruitment underneath protrusions (Figure 4B), while only minimally affecting apical PIP3 recruitment (Figures 4A, S3B). Our findings indicate that both PIP3 production by PI3K and actin reorganization mediated by Rac1 are required for protrusion formation. Furthermore, our results suggest that actin reorganization at protrusions occurs downstream of apical PIP3 generation.

Figure 4. PI3K and Rac1 are required for protrusion formation while PI3K, Rac1, and Par3 are required for aggregate-associated NFκB activation.

(a) The effect of chemical inhibition (LY29004 for PI3K, Rac1 inhibitor for Rac1, SC-514 for NFκB; black bars) or shRNA-mediated protein depletion (gray bars) on the recruitment of PIP3 to the protrusion as judged by recruitment of PH-Akt-GFP to the protrusion. In control experiments, PH-Akt-GFP was recruited to 82% (“control”) and 86% (“shScr”) of bacterial aggregates analyzed, and all results were normalized to controls (n ≥ 2 independent experiments). (b) The effect of chemical inhibition (black bars) or shRNA-mediated protein depletion (gray bars) on the recruitment of actin to the protrusion as judged by fluorescent phalloidin staining. All results were normalized to controls (n≥2 independent experiments). (c) Chemical inhibition of PI3K, Rac1, or NFκB does not affect Par3 recruitment to the protrusion. (d) Western blot for Par3 in untreated, shScr-expressing, or shPar3-expressing MDCK cells. The two major Par3 isoforms are indicated with an asterisk. GAPDH serves as a loading control. (e) NFκB activation underneath bacterial aggregates following chemical inhibition (black bars) or shRNA mediated protein depletion (gray bars). NFκB activation was scored the same as in Figure 2B (n≥2 independent experiments). Data are mean ± SEM. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 compared to control. See also Figures S3B, S4, and Statistics in Supplemental Data.

We similarly examined the effect of PI3K and Rac1 inhibition on recruitment of Par3. Par3 is known to bind a number of proteins, including PI3K, the Rac1-specific guanine-nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1 (Rodriguez-Boulan and Macara, 2014), and the GTPase activating protein Bcr (Narayanan et al., 2013). Thus, Par3 could locally control the activity of PI3K and Rac1 at the protrusion by linking these molecules into a complex. Par3 recruitment to protrusions was not affected by inhibiting PI3K or Rac1 (Figure 4C), suggesting that its localization to the protrusion occurs prior to, or independently of, PI3K or Rac1 activity. ShRNA-mediated depletion of Par3 decreased F-actin recruitment to protrusion by approximately 40% (Figure 4B), while only minimally affecting PIP3 recruitment (Figure 4A). These data suggest that Par3, possibly via Rac1, is involved in robust F-actin polymerization at protrusions, downstream of aggregate-induced apical PIP3 generation.

Protrusion formation is associated with a spatially localized innate immune response

We tested whether host components involved in protrusion formation were required for NFκB activation (Figure 4E). Aggregate-induced NFκB activation was almost completely abolished by PI3K inhibition (LY294002), confirming that ectopic apical PIP3 generation is a critical event in the host response. Likewise, Rac1 chemical inhibition or Par3 depletion resulted in a robust and significant reduction in NFκB activation similar to treatment with the IκB kinase-2 inhibitor SC-514. We eliminated the possibility that NFκB is required for protrusion formation by demonstrating that SC-514 had no effect on protrusion formation, as assessed by PIP3 or actin recruitment (Figures 4A and B). In summary, our results indicate an intimate association between protrusion formation and NFκB activation, with PI3K activity, Rac1, and Par3 required for both processes. Our data suggest that—in response to the binding of bacterial aggregates—protrusion formation may play a critical role in generating a spatially localized innate immune response at the epithelial surface.

Discussion

How epithelial cells specifically recognize microbial pathogens and activate an effective immune response is a central issue in understanding host-pathogen interactions. In this work, we describe a role for cell polarity proteins in innate immunity to P. aeruginosa infection. Our results allow us to construct an integrated model for the cellular signaling events involved in innate immunity to P. aeruginosa (Figure S4), which may be applicable to other mucosal pathogens.

The first step in the remarkable membrane remodeling of the apical surface is the recruitment of individual free-swimming bacteria to multicellular aggregates on the host cell surface, often at cell-cell junctions (Lepanto et al., 2011). Time-lapse videomicroscopy demonstrated that, in intact epithelium, protrusions were formed de novo in response to aggregate binding, as opposed to the aggregates binding to pre-existing protrusions. This process is rapid and dynamic, potentially allowing for tightly controlled activation of downstream pathways. Par3 and PI3K are recruited to the site of aggregate binding, leading to ectopic production of PIP3. Recruitment of Rac1, along with aPKC-Par6α and additional AJ proteins, completes the transformation of a small patch of apical membrane to a basolateral-like protrusion rich in F-actin. We observed recruitment of AJ proteins but not TJ proteins, suggesting that P. aeruginosa aggregate binding results in the de novo formation of a primordial AJ at the site of aggregate binding. Of note, these events occur early, within 30 minutes of infection. At later times, after translocation of the T3SS effectors or other virulence factors, cell-cell junctions and epithelial polarity can be disrupted (Kang et al., 1997; Soong et al., 2008).

Protrusion formation is associated with spatially and temporally localized translocation of NFκB, to the nucleus, indicating activation of an innate immune response to bacterial aggregates. Neither protrusion formation nor NFκB activation were observed upon binding of individual bacteria, suggesting that either a minimal number of bacteria are required to incite this response or that the bacterial aggregates have distinct functional characteristics. We favor the latter possibility because we have not found a correlation between the number of bound bacteria contained within the aggregate, the size of the protrusion, or the activation of NFκB (C. Tran and J. Engel, unpublished data).

T3SS needle and translocon mutants induced protrusions but not NFκB activation, suggesting that protrusion formation is necessary but not sufficient for activation of the innate immune response. We postulate that protrusion formation is part of a crucial first step in a signaling cascade within the epithelial cell that ultimately results in NFκB activation. However, additional host components may be necessary for activation of the localized innate immune response.

This process may be triggered by T3SS pore formation and/or flagella. Our work complements and extends previous studies that showed that flagellar-mediated binding of P. aeruginosa to the basolateral surface of polarized CFTR-deficient airways cells resulted in robust activation of NFκB at 4 hr post-infection (Hybiske et al., 2004). Both cytosolic flagellin and the rod component of the T3SS apparatus are sensed by NLRC4, although their detection involves distinct accessory proteins (Kofoed and Vance, 2011). Flagella can also activate NFκB through TLR5 (Gewirtz et al., 2001). How detection of the T3SS or flagella are linked to Par3 and PI3K is still unknown but may represent a sensing mechanism in polarized epithelial cells. It will be of interest to determine whether TLR5 is recruited or is required for protrusion formation and NFkB activation.

Our results suggest that changes in host cell polarity may function as a danger signal that alerts the host to the presence of a pathogen. In addition to conserved microbial products such as LPS or peptidoglycan, host cell components, including glycans and actin, as well as pathogen-induced alteration of small GTPase signaling pathways, have been shown to function as danger signals that are sensed by immune cells (Ahrens et al., 2012; Cerliani et al., 2011; Keestra et al., 2013; Varki, 2011). Thus, perturbations in cell polarity may be sensed by epithelial cells as an early warning system for detecting the presence of mucosal pathogens that target junctional complexes.

This work underscores an emerging theme that host cell polarity determinants are important targets by which specific pathogens subvert epithelial or endothelial barriers, though the consequences can be vastly different. The endothelial pathogen Neisseria meningitides has been shown to recruit the Par3/Par6/aPKC complex away from TJs in endothelial cells, weakening the intercellular barrier and providing an explanation for disruption of the blood brain barrier (Coureuil et al., 2010; Coureuil et al., 2009). Rhesus papillomavirus type 1 (RPV1) targets Par3 for degradation during infection, which facilitates barrier breakdown (Tomaic et al., 2009). In contrast, initial binding of P. aeruginosa aggregates is accompanied by augmentation of the barrier, as evidenced by enhanced transepithelial resistance (Kierbel et al., 2007).

Given our data showing that Par3 is involved in the innate immune response, we speculate that RPV1 and N. meningitides may target the Par complex not only to bypass the physical barrier of the epithelium but also to block activation of the innate immune system. The ability to subvert Par3 function could represent an intermediate step in the evolution of a pathogen; as an opportunistic pathogen, P. aeruginosa activates the innate immune response but lacks the virulence capacity to initiate destruction of the epithelial barrier at early time points. In contrast, more potent pathogens may have the ability to subvert or destroy Par3 to circumvent the epithelial/endothelial barrier. These studies illustrate the sophisticated interplay between pathogen-directed damage and the host response and highlight the Par complex as a key target of both pathogen and host defense systems.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains, reagents, antibodies, cell lines, RNAi, microscopy, and statistical analysis are described in Supplemental Methods.

Analysis of protein recruitment to protrusions

Images were analyzed with NIS Elements software (Nikon Instruments Inc.) to assess recruitment of the protein of interest to bacterial binding sites. MDCK cells that were bound to aggregates of ≥ 10 bacteria were included for analysis. Internalized bacterial aggregates and aggregates located near extruded MDCK cells were excluded from analysis. After ensuring that the protein of interest showed appropriate localization in the surrounding epithelial cells, the three-dimensional space within and adjacent to the bacterial aggregate was examined for protein recruitment. Recruitment was scored as positive if the protein of interest was found on or above the apical surface of the cell and if the fluorescent intensity was equal to the intensity at basolateral or junctional locations. In pilot studies to ensure minimal inter-observer variability, over 90 images were independently analyzed by two observers, with less than 10% variation in scoring. Results are reported for n ≥ 2 and at least 14 bacterial aggregate binding events for each protein of interest or condition. For experiments with chemical inhibitor or shRNA treatments, appropriate negative controls (no treatment or scrambled shRNA) were used for statistical comparisons. Results were normalized to control experiments.

Quantitative analysis of NFκB localization

Confocal microscopy images were analyzed with NIS Elements software (Nikon Instruments Inc.) to quantify NFκB p65 nuclear and cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity. A confocal Z-slice with the strongest DAPI signal was chosen for analysis from each confocal image stack. For each cell in contact with an aggregate of ≥10 bacteria, ROIs were defined for the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and sum fluorescence intensity of NFκB p65 was quantified in each ROI. To establish an appropriate negative control value, we determined the nuclear and cytoplasmic sum fluorescence intensity of NFκB p65 in 600 uninfected MDCK cells from three independent experiments (Figure S1). All cells showed a ratio of nuclear/cytoplasmic p65 fluorescence intensity of <1, with an average ratio of 0.47 ± 0.08 SD; we therefore defined NFκB nuclear activation as a nuclear/cytoplasmic p65 fluorescence ratio of ≥ 1. Results are reported for n ≥ 2 and at least 20 bacterial aggregate binding events for each bacterial strain or treatment condition.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Actin-rich apical membrane protrusions form de novo at P. aeruginosa aggregation sites

Epithelial cell apical protrusion formation is associated with localized activation of NFκB

Protrusion formation and localized NFκB activation require bacterial flagella and T3SS

Par3, Rac1, and PI3K are recruited to protrusions and required for NFκB activation

Acknowledgments

We thank Kurt Thorn and the UCSF Nikon Imaging Center for assistance with microscopy. Financial support was provided by EMBO (Y.E.), NIH RO1 AI065902 (J.N.E.), PO1 AI53194 (J.N.E. and K.E.M.), K99CA163535 (D.M.B), K12 HD072222 (C.S.T.), K12 HD000850 (C.S.T.), and K08 DK068358 (P.B.)

Footnotes

Author contributions

C.S.T. and Y.E. contributed equally to design of experiments, performance of experiments, analysis of the data, and writing of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahrens S, Zelenay S, Sancho D, Hanc P, Kjaer S, Feest C, Fletcher G, Durkin C, Postigo A, Skehel M, et al. F-actin is an evolutionarily conserved damage-associated molecular pattern recognized by DNGR-1, a receptor for dead cells. Immunity. 2012;36:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artis D. Epithelial-cell recognition of commensal bacteria and maintenance of immune homeostasis in the gut. Nature reviews Immunology. 2008;8:411–420. doi: 10.1038/nri2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran P, Dragone L, Garrity-Ryan L, Lemus A, Weiss A, Engel J. The ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b limits Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin T-mediated virulence. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:419–427. doi: 10.1172/JCI28792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucior I, Mostov K, Engel JN. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-mediated damage requires distinct receptors at the apical and basolateral surfaces of the polarized epithelium. Infection and immunity. 2010;78:939–953. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01215-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucior I, Pielage JF, Engel JN. Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili and flagella mediate distinct binding and signaling events at the apical and basolateral surface of airway epithelium. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8:e1002616. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerliani JP, Stowell SR, Mascanfroni ID, Arthur CM, Cummings RD, Rabinovich GA. Expanding the universe of cytokines and pattern recognition receptors: galectins and glycans in innate immunity. Journal of clinical immunology. 2011;31:10–21. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coureuil M, Lecuyer H, Scott MG, Boularan C, Enslen H, Soyer M, Mikaty G, Bourdoulous S, Nassif X, Marullo S. Meningococcus Hijacks a beta2-adrenoceptor/beta-Arrestin pathway to cross brain microvasculature endothelium. Cell. 2010;143:1149–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coureuil M, Mikaty G, Miller F, Lecuyer H, Bernard C, Bourdoulous S, Dumenil G, Mege RM, Weksler BB, Romero IA, et al. Meningococcal Type IV Pili Recruit the Polarity Complex to Cross the Brain Endothelium. Science. 2009;325:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1173196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech MP, Corvera S. Signaling mechanisms that regulate glucose transport. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:1865–1868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMango E, Ratner AJ, Bryan R, Tabibi S, Prince A. Activation of NF-KB by adherent Pseudomonas aeruginosa in normal and cystic fibrosis respiratory epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2598–2606. doi: 10.1172/JCI2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J, Balachandran P. Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III effectors in disease. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AT, Navas TA, Lyons S, Godowski PJ, Madara JL. Cutting edge: bacterial flagellin activates basolaterally expressed TLR5 to induce epithelial proinflammatory gene expression. Journal of immunology. 2001;167:1882–1885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha U, Jin S. Growth phase-dependent invasion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its survival within HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4398–4406. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4398-4406.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hybiske K, Ichikawa JK, Huang V, Lory SJ, Machen TE. Cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cell polarity and bacterial flagellin determine host response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:49–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang PJ, Hauser AR, Apodaca G, Fleiszig SM, Wiener-Kronish J, Mostov K, Engel JN. Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa genes required for epithelial cell injury. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1249–1262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4311793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak B, Mostov K, Engel J. Interaction of bacterial pathogens with polarized epithelium. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:407–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keestra AM, Winter MG, Auburger JJ, Frassle SP, Xavier MN, Winter SE, Kim A, Poon V, Ravesloot MM, Waldenmaier JF, et al. Manipulation of small Rho GTPases is a pathogen-induced process detected by NOD1. Nature. 2013;496:233–237. doi: 10.1038/nature12025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierbel A, Gassama-Diagne A, Rocha C, Radoshevich L, Olson J, Mostov K, Engel J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exploits a PIP3-dependent pathway to transform apical into basolateral membrane. The Journal of cell biology. 2007;177:21–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofoed EM, Vance RE. Innate immune recognition of bacterial ligands by NAIPs determines inflammasome specificity. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie EG, Wangdi T, Kazmierczak BI. Innate immune responses to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur. 2011;13:1133–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepanto P, Bryant DM, Rossello J, Datta A, Mostov KE, Kierbel A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa interacts with epithelial cells rapidly forming aggregates that are internalized by a Lyn-dependent mechanism. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:1212–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macara IG. Parsing the polarity code. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2004;5:220–231. doi: 10.1038/nrm1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mijares LA, Wangdi T, Sokol C, Homer R, Medzhitov R, Kazmierczak BI. Airway Epithelial MyD88 Restores Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Murine Infection via an IL-1-Dependent Pathway. J Immunol. 2011;186:7080–7088. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostov KE. Regulation of protein traffic in polarized epithelial cells. Histol Histopathol. 1995;10:423–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan AS, Reyes SB, Um K, McCarty JH, Tolias KF. The Rac-GAP Bcr is a novel regulator of the Par complex that controls cell polarity. Molecular biology of the cell. 2013;24:3857–3868. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-06-0333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Boulan E, Macara IG. Organization and execution of the epithelial polarity programme. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2014;15:225–242. doi: 10.1038/nrm3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JH, Kim CH, Yoon JH. Innate immune responses of the airway epithelium. Molecules and cells. 2010;30:173–183. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadikot RT, Zeng H, Joo M, Everhart MB, Sherrill TP, Li B, Cheng DS, Yull FE, Christman JW, Blackwell TS. Targeted immunomodulation of the NF-kappaB pathway in airway epithelium impacts host defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of immunology. 2006;176:4923–4930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder TH, Lee MM, Yacono PW, Cannon CL, Gerceker AA, Golan DE, Pier GB. CFTR is a pattern recognition molecule that extracts Pseudomonas aeruginosa LPS from the outer membrane into epithelial cells and activates NF-kappa B translocation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:6907–6912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092160899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong G, Parker D, Magargee M, Prince AS. The type III toxins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa disrupt epithelial barrier function. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2814–2821. doi: 10.1128/JB.01567-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekuni K, Ikeda W, Fujito T, Morimoto K, Takeuchi M, Monden M, Takai Y. Direct binding of cell polarity protein PAR-3 to cell-cell adhesion molecule nectin at neuroepithelial cells of developing mouse. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:5497–5500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaic V, Gardiol D, Massimi P, Ozbun M, Myers M, Banks L. Human and primate tumour viruses use PDZ binding as an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of targeting cell polarity regulators. Oncogene. 2009;28:1–8. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A. Since there are PAMPs and DAMPs, there must be SAMPs? Glycan “self-associated molecular patterns” dampen innate immunity, but pathogens can mimic them. Glycobiology. 2011;21:1121–1124. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watton SJ, Downward J. Akt/PKB localisation and 3′ phosphoinositide generation at sites of epithelial cell-matrix and cell-cell interaction. Current biology : CB. 1999;9:433–436. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.