In 2012, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is about to enter another important phase of development, therapeutics. For 20 years, the echoendoscope has been used to image the gastrointestinal tract and adjacent organs. The unique imaging afforded by EUS has been the most important development in gastrointestinal endoscopy over the past 20 years. EUS imaging has improved our understanding of many disease states, including mucosal gastric and esophageal cancers, early pancreatic malignancy, and nodal metastases. The first revolution in EUS came with the development of fine needle aspiration. Coupled with linear EUS, FNA provided another diagnostic tool for improving the specificity of EUS findings of malignancy as well as infections (Fig. 1). Using the same imaging capabilities, coupled with new tools and strong concepts, the echoendoscope can now lead the development of therapeutics. Therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound has been awaiting the availability of new instruments and accessories that will allow endoscopists to access therapeutic targets such as the pancreas. What will it take to achieve this goal? In the 2012 summer Olympics, achievement is possible through speed, strength, or coordination. Achievement in the therapeutic endoscopy Olympics will also require speed, strength, and coordination. The Therapeutic Endoscopy Olympics will feature interventional radiology, minimally invasive surgery versus therapeutic endoscopy, including therapeutic EUS.

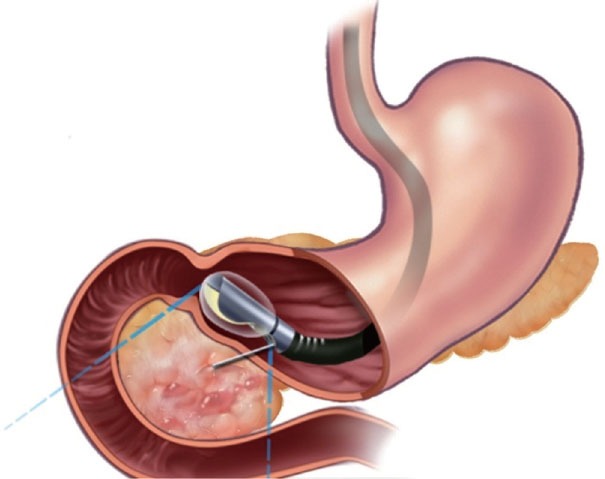

Figure 1.

Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration.

The most likely prospect for winning a gold medal by therapeutic EUS is pseudocyst drainage. Using new therapeutic tools, EUS could excel past minimally invasive surgery and interventional radiology for management of pseudocysts1. For speed, we will need a dedicated EUS needle and wire introducer that can provide quick and certain access to simple pseudocysts as well as complex fluid collections containing foci of tissue necrosis2. For strength, we will need a dedicated stent introducer that can provide a large and secure cyst-gastrostomy. With the ability to use a secure cyst-gastrostomy, endoscopic access to the pseudocyst cavity will be assured and provide an opportunity to drain and dissect areas of tissue necrosis. New tools will enable the endoscopist to safely resect necrotic tissue from viable structures, including important vascular landmarks such as the splenic artery and vein. These tools might be soft snares, nets, and gasping forceps that have not been designed yet for endoscopy. For coordination, we will need research, published trials, and rapid communication. These communication tools can be provided by a dedicated EUS journal that will provide endosonographers with the means to formally present the results of important new trials of devices in the context of traditional EUS manuscripts. I think “Endoscopic Ultrasound” will be an important new journal for endoscopists and fills an obvious void in the medical publishing world. It is remarkable to consider how an important endoscopic technique does not have a dedicated journal.

The silver medal in the Therapeutic Endoscopy Olympics will likely go to pancreas cyst ablation therapy. Using new therapeutic tools, EUS could win the race against surgical resection and medical therapy. For speed, we will need a dedicated EUS injection needle that can provide quick and certain access to cystic structures that represent intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. The therapeutic EUS needle will allow the endosonographer to inject ablative agents such as ethanol, taxol, or anti-proliferative drugs3. However, the therapeutic needle could also provide access for ablative devices such radiofrequency catheters or brachytherapy seeds. For strength, we will need devices that can ablate intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) with confidence, endurance, and accuracy. It is possible, that a single agent or device will not be able to provide us with the strength needed to confidently eradicate all the abnormal tissue present in an IPMN. Perhaps we will need the synergy offered by the local heat of radiofrequency ablation and the toxic tissue contact with ethanol. For coordination, we will need critical reviewers who can assist EUS investigators in presenting the findings of important trials or investigations in an objective and scientific manner. A dedicated EUS journal might offer such an opportunity to the EUS community. “Endoscopic Ultrasound” has an outstanding editorial board who are anxious to work with authors and reviewers in the search for outstanding EUS manuscripts. With the anticipated increase in the number of endoscopic trials that involve therapeutic EUS, the availability of a new EUS journal will be very welcome.

The bronze medal will go to EUS-guided stent and drainage placement in the pancreatic or biliary ductal system. ERCP has had a stronghold on this technique for 30 years and the limitations of this approach are well recognized by clinicians worldwide4. Although endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) guided stenting of the bile duct is very successful, there are important limitations. EUS may play a complementary role in the guidance of stents into the biliary tree under conditions whereby ERCP may not have a high degree of success5. The most obvious and apparent clinical challenge is duodenal obstruction that results in the inability to gain ERCP access to the biliary ampulla6. Patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who present with gastric outlet obstruction and jaundice are the most obvious candidates. Because ERCP may not be able to access the duodenum and the biliary ampulla, alternatives to ERCP stenting are important. The traditional alternative to ERCP stenting is transhepatic biliary drainage. EUS may be able to guide the placement of guidewires and catheters to the bile duct--- from the stomach. EUS access catheters that will allow rapid placement of stents across the duodenal or gastric wall and into the biliary tree or gallbladder7. Speed should be assured through the use of well-designed access needles and guidewires for quick and accurate placement of plastic or self-expanding stents. Strength will be important when it comes to the safety of EUS guided stent placement. The EUS stents may need to offer a design different from the simple plastic stents used in by ERCP -- in order to minimize the risk of bile leaks and infections. For coordination, we will need a venue to convince our surgical and medical colleagues that therapeutic EUS offers some important alternatives to traditional endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical approaches. A dedicated EUS journal with a focus on critical reviews by experts in EUS and therapeutic EUS will offer the potential for a strong and speedy communication to the medical community. Journal publication on-line and in print is critical in the development of new techniques and approaches to common medical issues.

In summary, “Endoscopic Ultrasound” is a new journal dedicated to the dissemination of medical information demonstrating novel results of investigations, trials, or case series. I have focused on three prominent therapeutic EUS techniques, pseudocyst drainage, IPMN ablation therapy, and biliary drainage. However, there are many other novel EUS diagnostic and therapeutic techniques that await further evaluation. We welcome submissions from throughout the world endoscopy community. We can promise you quick and efficient reviews and timely publication in on-line format as well as in a print format.

REFERENCES

- 1.Samuelson AL, Shah RJ. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2012;41:47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berzosa M, Maheshwari S, Patel KK, et al. Single-step endoscopic ultrasonography-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections with a single self-expandable metal stent and standard linear echoendoscope. Endoscopy. 2012;44:543–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon WJ, Brugge WR. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided tumor ablation. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22:359–69. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhir V, Bhandari S, Bapat M, et al. Comparison of EUS-guided rendezvous and precut papillotomy techniques for biliary access (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholson JA, Johnstone M, Raraty MG, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledoco-duodenostomy as an alternative to percutaneous trans-hepatic cholangiography. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14:483–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon WJ, Brugge WR. EUS-guided biliary rendezvous: EUS to the rescue. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:360–1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang JW, Lee SS, Song TJ, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage are comparable for acute cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:805–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]