Abstract

Objective:

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage is a widely used treatment modality for pancreatic pseudocysts (PPC). However, data on the clinical outcome and complication rates are conflicting. Our study aims to evaluate the rates of technical success, treatment success and complications of EUS-guided PPC drainage in a medium-term follow-up of 45 weeks.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective review was conducted for 55 patients with symptomatic PPC from December 2005 to August 2010 drained by EUS. Medium-term follow-up data were obtained by searching their medical history or by telephonic interview.

Results:

A total of 61 procedures were performed. The symptoms that indicated drainage were abdominal pain (n = 43), vomiting (n = 7) and jaundice (n = 5). The procedure was technically successful in 57 of the 61 procedures (93%). The immediate complication rate was 5%. At a mean follow-up of 45 weeks, the treatment success was 75%. The medium term complications appeared in 25% of cases, which included three cases each of stent clogging, stent migration, infection and six cases of recurrence. There was no mortality.

Conclusion:

EUS-guided drainage is an effective treatment for PPC with a successful outcome in most of patients. Most of the complications require minimal invasive surgical treatment or repeated EUS-guided drainage procedures.

Keywords: endoscopic ultrasound, pancreatic pseudocyst drinage, pancreatic cyst

INTRODUCTION

A pancreatic pseudocyst (PPC) is a localized collection of fluid rich in amylase, located within or adjacent to the pancreas and enclosed by a non-epithelial wall, which may develop as a consequence of pancreatic inflammation or injury.1 Most of the pseudocysts are asymptomatic and resolve spontaneously. Treatment is required only in the case of persisting PPCs causing symptoms such as abdominal pain, complicated with infection or compression of the gastrointestinal tract, pancreatic duct or the common bile duct. Management of PPCs has traditionally been surgical. Surgery, however, is associated with a significant percentage of complications and even mortality.2

Endoscopic drainage is a minimally invasive alternative, which may be performed by a trans-papillary or a trans-mural approach. Drainage of the cyst fluid by the trans-mural approach is achieved by inserting a stent between the pseudocyst and the gastric lumen (cystogastrostomy) or between the pseudocyst and the duodenal lumen (cystoduodenostomy). The drainage procedure may either be performed by endoscopy as a “semi-blind” procedure if an impression caused by the cyst is present or by direct endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) guidance. The latter method is believed to be less risky since interposed vessels can be avoided during the creation of the fistula tract between the pseudocyst and the gut lumen.

In recent years, EUS-guided PPC drainage has become the treatment of choice in many reference centres. However, there are only a few medium-term outcome studies to date. The aim of the present retrospective study is to evaluate the success rate, medium-term clinical outcome and complications of patients with symptomatic PPCs treated by trans-mural cyst drainage under EUS-guidance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study cohort was composed of 55 patients with symptomatic PPC referred for EUS-guided drainage over an 80-month period, between January 2005 and August 2010, at Gentofte Hospital in Denmark and Research Center of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Craiova in Romania. A total of 61 procedures were performed. Their early and late clinical outcomes were retrospectively reviewed. The cause and management of complications were also described.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All consecutive patients between 18 and 85 years of age referred for EUS-guided examinations of simple (i.e., homogenous, with clear fluid inside), symptomatic PPC were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were cystic tumors, small asymptomatic pseudocysts (<5 cm) or complicated pseudocysts (multiloculated), presence of large intervening vessels on power Doppler or absence of a clear access to the pseudocyst content (distance higher than 10 mm), severe coagulopathies, uncorrectable severe platelet dysfunction or the failure to provide informed consent.

Procedures

Informed consent was obtained from every patient prior to EUS-guided drainage. The sequence of individual procedural steps could be delineated as follows:

The ultrasound endoscope was advanced to the stomach or the duodenum.

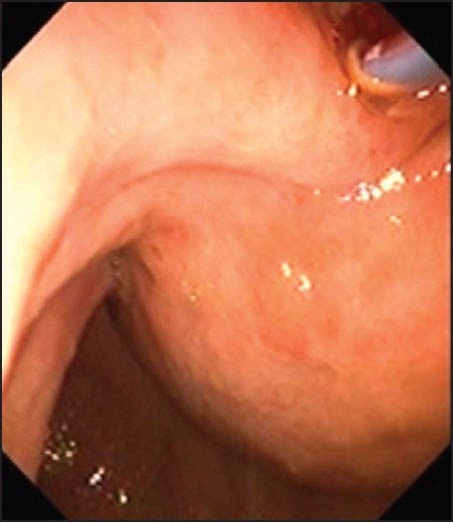

The PPC and the pancreas were delineated by EUS and a location most suitable for the puncture was selected. Doppler imaging was used to avoid any interposed vessels (Fig. 1).

The pseudocyst was punctured using a Giovannini needle (Fig. 2) or alternatively a 19-G aspiration needle (Fig. 3).

A guidewire was advanced over the needle and coiled-up inside the pseudocyst (Fig. 4).

The 19-G needle was then retracted.

A dilation catheter with a diameter of 8-10 mm was used to enlarge the tract (Fig. 5). In some cases it was necessary to enter using electrocauthery by means of a cystotome.

One or two stents of size 7 Fr or 10 Fr. were subsequently inserted (Fig. 6).

Figure 1.

The pancreatic pseudocysts and the pancreas were delineated by endoscopic ultrasound and a location most suitable for the puncture was selected. Doppler imaging was used to avoid any interposed vessels

Figure 2.

The pseudocyst was punctured using a Giovannini needle

Figure 3.

The pseudocyst was punctured using a 19-G aspiration needle

Figure 4.

A guidewire was advanced over the needle and coiled-up inside the pseudocyst

Figure 5.

A dilation catheter with a diameter of 8-10 mm was used to enlarge the tract

Figure 6.

One stent was subsequently inserted

In order to evaluate the medium-term results of the drainage procedure, a follow-up was done by either search for the medical history of the patients succeeding the drainage procedure or by telephone interview of patients or the referring department.

Definitions

Technical success was defined as access and drainage of the PPC by the placement of stent. Treatment success was defined as disappearance of symptoms with either a decrease in size (over than 50%) or complete resolution of the PPC.

RESULTS

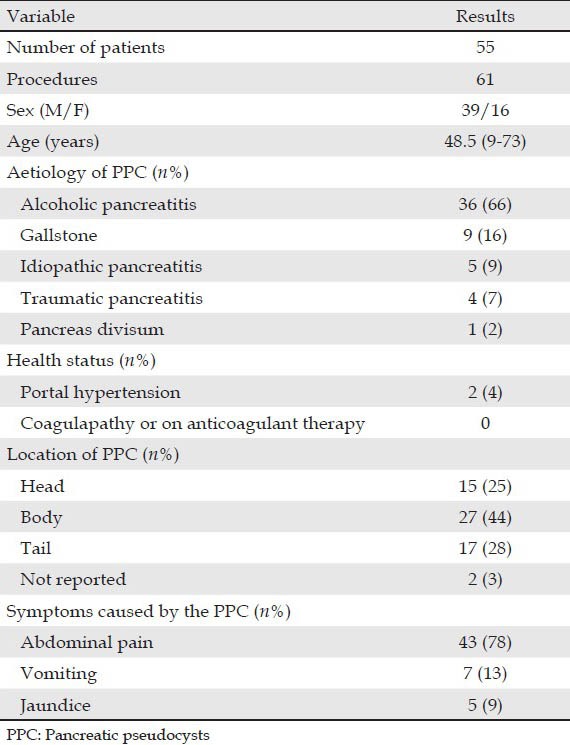

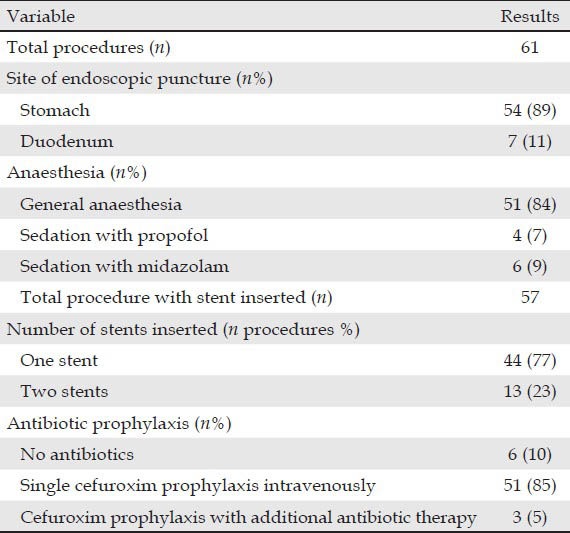

Demographic data for the 55 patients are displayed in Tab. 1. The patient group included 39 men and 16 women, with a median age of 48.5 years (ranging from 9 to 73 years). A total of 61 procedures were performed (Tab. 2). The etiology of PPCs included acute and chronic pancreatitis: Alcoholic in 36 cases, gallstone in nine, idiopathic in five, post-traumatic in four and pancreas divisum in one case. PPCs were caused by acute pancreatitis in three patients and by chronic pancreatitis in 52 patients. Their presenting symptoms were abdominal pain (n = 43), vomiting (n = 7) and jaundice (n = 5). The pseudocysts were located in the pancreatic head in 15 cases, in the body in 27, in the tail in 17 and unknown in two cases. The average pseudocyst diameter was 7.5 (3-20) cm based. There were 51 procedures performed under general anesthesia, six under midazolam and four under propofol.

Table 1.

Demographic data on patients

Table 2.

Data on the procedure

The technique of drainage included the use of the Giovannini needle knife and cautery and of the 19-G needle with balloon dilation. The choice of the technique was based on the decision of the examining doctor, as well as on availability. Moreover, the technique was modified during the learning curve, based on local expertise and preference during the development of the method. The use of the cystotome was necessary only in a few cases, because the pseudocyts wall was too thick and prevented dilation after passage of the initial 19-G needle.

Early outcome of endoscopic treatment

The puncture was attempted through the transgastric route in 54 procedures (89%) and through the transduodenal route in seven procedures (11%). 57 procedures were successful with a technical success rate of 93%, while four procedures were unsuccessful. For the first case, it was impossible to bring the endoscope to a favourable position for puncture, due to the position of the pseudocyst towards the uncinate process. In the second patient, the guidewire was displaced several times. No attempt was made to enlarge the fistula tract or to insert a stent. In the third patient, the opening created between the cyst and the stomach was found too large to support a stent. A week later another endoscopist was able to successfully place two double pigtail stents via the opening. For the last patient, the stent was lost into the PPC and failed endoscopic removal. There were three immediate complications (5%). One case was the patient with the stent lost into the pseudocyst just mentioned. Surgical cystogastrostomy was performed. Another case was associated with perforation of the gallbladder, which was managed by surgery. Bleeding occurred in one patient, being successfully treated by surgery. There was no mortality in all cases. Most of the early complications thus occurred in the first 20 patients included in each tertiary reference center. Thus, there were 13 complications in the first 40 procedures, as compared to the rest of procedures, where the percentage of complications was only 13%.

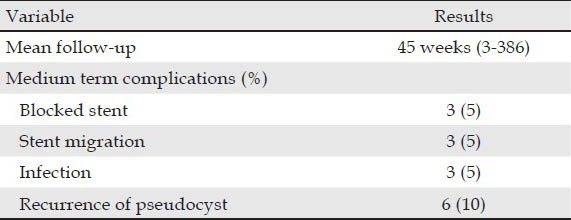

Medium-term outcome of the endoscopic treatment

The mean follow-up was 45 weeks [range: 3-386 weeks (Tab. 3)]. The treatment success rate was 75%. Stent clogging occurred in 3 (5%) patients. One patient had a complicated evolution with infection and recurrence of the PPC and was managed with a nasocystic drain. The other two cases were treated with endoscopic replacement with a second stent. There was stent migration in 3 (5%) patients. In two cases the migrated stents were replaced with new stents under a repeated EUS-guided procedure. The repeated procedures with placement of second stents successfully drained the pseudocyst and induced symptom resolution. In the third case an attempt to replace the migrated stent was unsuccessful. There were 3 (5%) cases of infection. All three cases underwent surgical cystogastrostomy. There were 6 (10%) cases of recurrence of PPC. One patient developed a new pseudocyst in the pancreatic tail, which was later proven to be malignant. The tumour was removed by radical excision. Another patient developed a PPC in the follow-up period that mechanically obstructed the pancreatic duct. This case was managed by insertion of a stent in the pancreatic duct using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, 19 days after PPC drainage. One patient developed an asymptomatic persistent PPC despite stent placement. No further treatment was performed in this case. For the other cases, EUS-guided PPC drainage was performed with replacement of stents.

Table 3.

Follow-up on the stents

DISCUSSION

Although the study pooled the patients from two tertiary referral centers, the technique used was similar, with initial EUS-guided puncture of the pseudocyst through the stomach or duodenal wall, followed by dilatation and stent placement. The technique was slightly modified in both centers during the learning curve, with a decreased use of electrocautery (with “cut” current) during the initial puncture, which was performed by means of a 19-G EUS needle, followed by guidewire placement and subsequent dilation with baloons and dilatators. This had important consequences, as the percentage of complications decreased in the second half of the patients included.

This study has a medium period of follow-up of 45 weeks. We demonstrated the treatment success rate in EUS-guided PPC drainage was only 74.5%. This was quite different from previous studies with success ranging from 82% to 100%.3,4,5 This may be due to the fact that we have a longer period of follow-up as compared to other published studies. In the longest follow-up study of 48 months, the technical success rate was 92% with a recurrence rate of 16.7%.6

Our study series showed a case of gallbladder perforation. This had never been mentioned in previous literature for PPC drainage after EUS-guided drainage and it was probably determined by slippage of the needle knife on the surface of a very hard pseudocyst. We had only one (2%) case of bleeding complication. A previous study7 showed that there was a bleeding complication rate of 10%. This may be due to the fact that we had only two cases of patients with portal hypertension. The infection rate in our series was 5%. In comparison with a previous study, there was no case of infection.8 In their study, all patients received prophylactic antibiotics that were continued for 3 days after the procedure and they placed 61% of the patients on jejunal feeding to provide strict pancreatic rest.

There were three patients with stents migrated into stomach. This condition could often be managed by conservative treatment in asymptomatic case.9 However, if the patient suffered a relapse, a new stent was usually necessary.3,4,10 In our study, three of the patients (5%) developed symptomatic recurrence of PPC due to stent migration into the gastrointestinal tract. Another case with complication was clogging of the stent resulting in recurrence of PPC. Stent clogging is a repeatedly reported complication that causes recurrence of the PPCs.4,10,11,12 There was no mortality recorded, while the other published studies revealed a variable mortality rate of 0-7%.2,4,5,10,11,12,13,14,15

Medium-term clinical outcome of our patients were evaluated in the study with mean follow-up time of 45 weeks. The symptomatic recurrence rate was 10%. These patients were treated by another endoscopic procedure and recovered successfully. Other studies revealed that the rate of recurrence after endoscopic drainage ranges between 6% and 23% with a medium standing follow-up.2,11

Small pseudocysts (<5 cm) usually do not require treatment, unless they are symptomatic, a situation when transpapillary drainage might be recommended according to European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines.16 Nevertheless, most of our patients had pseudocysts larger than 5 cm, which are amenable to initial EUS-guided drainage, regardless of the communicating status between the pseudocyst and the pancreatic duct. One of the limitations of our study was the retrospective nature and inclusion of patients in two centers. Thus, the proficiency of examiners during the learning curve was probably responsible for the development of some complications, as most of the complications ocurred in the first 20 patients in each center. Although it is not clear what is the best number of EUS-guided drainage procedures, based on the authors’opinion and the results of the study, a number of 20 procedures supervised in a tertiary center with extensive experience in therapeutic EUS procedures might be enough for further performance of the technique with minimal complications. However, there are no studies at present that can document this and the level of evidence is therefore low. This was also paralleled by a change in the EUS-guided drainage technique, as the techniques using diatermy being gradually replaced by a technique using no current and dilation of the puncture tract with various devices.

CONCLUSION

EUS-guided drainage of PPCs is a technically challenging procedure, which is not successful in all cases. The procedure should be performed in tertiary centers with good support and under expert hands, with supervised procedures for at least 20 cases. The patients should be followed-up for any medium-term complications.

REFERENCES

- 1.Habashi S, Draganov PV. Pancreatic pseudocyst. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:38–47. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams DB, Anderson MC. Percutaneous catheter drainage compared with internal drainage in the management of pancreatic pseudocyst. Ann Surg. 1992;215:571–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199206000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahlawat SK, Charabaty-Pishvaian A, Jackson PG, et al. Single-step EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage using a large channel linear array echoendoscope and cystotome: Results in 11 patients. JOP. 2006;7:616–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopes CV, Pesenti C, Bories E, et al. Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts and abscesses. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:524–9. doi: 10.1080/00365520601065093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Tamhane A, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasuda I, Iwata K, Mukai T, et al. EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage. Dig Endosc. 2009;21(Suppl 1):S82–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antillon MR, Shah RJ, Stiegmann G, et al. Single-step EUS-guided transmural drainage of simple and complicated pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:797–803. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varadarajulu S, Tamhane A, Blakely J. Graded dilation technique for EUS-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections: An assessment of outcomes and complications and technical proficiency (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:656–66. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.03.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuchs M, Reimann FM, Gaebel C, et al. Treatment of infected pancreatic pseudocysts by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided cystogastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:654–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopes CV, Pesenti C, Bories E, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Arq Gastroenterol. 2008;45:17–21. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032008000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giovannini M, Bernardini D, Seitz JF. Cystogastrotomy entirely performed under endosonography guidance for pancreatic pseudocyst: Results in six patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:200–3. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inui K, Yoshino J, Okushima K, et al. EUS-guided one-step drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: Experience in 3 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:87–9. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.115473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azar RR, Oh YS, Janec EM, et al. Wire-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage by using a modified needle knife and therapeutic echoendoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:688–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, Bali MA, et al. Pancreatic-fluid collections: A randomized controlled trial regarding stent removal after endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:609–19. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vosoghi M, Sial S, Garrett B, et al. EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage: Review and experience at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. MedGenMed. 2002;4:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumonceau JM, Delhaye M, Tringali A, et al. Endoscopic treatment of chronic pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2012;44:784–800. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]