Abstract

Platelet satellitism (PS) is a rare phenomenon observed in blood smears obtained from blood anticoagulated with EDTA. It is characterised by platelet rosetting around polymorphonuclear neutrophils and in rare cases around other blood cells. PS is a rare cause of pseudothrombocytopenia. References about the phenomenon of PS in medical literature are few. In this report we describe a case of PS fortunately noticed in one trauma patient. Furthermore, we discuss the possible pathophysiological mechanisms of PS proposed in the literature. To our knowledge this is the first case of PS reported in Croatia.

Keywords: pseudothrombocytopenia, platelet satellitism, EDTA

Sažetak

Satelitizam trombocita (engl. platelet satellitism, PS) rijedak je fenomen primijećen u razmazima krvi tretirane antikoagulansom EDTA. Karakteriziran je formacijom trombocita u obliku rozete oko polimorfonuklearnih neutrofila i u rijetkim slučajevima oko drugih krvnih stanica. PS je rijedak uzrok pseudotrombocitopenije. U literaturi postoji malo referenci o PS. U ovom članku izvještavamo o slučaju PS koji je na sreću primijećen kod jednog pacijenta s traumom. Nadalje, raspravljamo o mogućim patofiziološkim mehanizmima PS koji se mogu naći u literaturi. Koliko znamo, ovo je prvi slučaj PS prijavljen u Hrvatskoj.

Introduction

Platelet satellitism (PS) is a rare in vitro phenomenon presenting with platelets rosetting around polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN). It is observed in peripheral blood smears prepared from blood samples anticoagulated with EDTA, but not in blood samples treated with heparin or sodium citrate (1–3). Platelet rosetting is observed mainly around PMN, but occasionally also around eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes or monocytes, too. Its clinical relevance is in the fact that it is a rare cause of spurious thrombocytopenia and, if not recognized, can lead to unnecessary treatment. It is not related to functional abnormalities of the blood, the patients clinical condition or to drug intake. The underlying mechanism of PS is not completely understood and there are a few studies trying to elucidate this platelet-leukocyte relationship (4).

References about PS in medical literature are few and not recent. There are only about a 100 cases described although this phenomenon is much more frequent, indicating that PS is not recognised, or simply not reported (5). To our knowledge this is the first case of PS reported in Croatia. In this case report we describe PS in a trauma patient, present an original figure of this phenomenon and discuss the possible mechanisms to better understand its nature.

Materials and methods

Case report

A 91-year-old woman was admitted to the University Hospital of Traumatology because of a left femoral fracture. Previous clinical history included senile dementia, deafness and blindness, and arterial hypertension. The patient was on hypertension therapy and “other drugs”, but because of her physical and mental condition, detailed information about previous medication intake could not be obtained. Immediately after admission, the patient was prepared for surgery, including preoperative laboratory workup (biochemistry, hematology and blood coagulation) and underwent surgery the same day. During surgery patient developed a myocardial infarction and respiratory failure and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further treatment. In the ICU, patient received antibiotic prophylaxis; antiparkinsonic, thromboprophylactic, antiulcer and analgesic therapy continuously, and volume replacement therapy. On the 1st and 5th day of ICU stay the patient received transfusion therapy (packed red blood cells). She developed a urinary tract infection and was treated with antibacterial therapy (norfloxacin) during the whole period of hospitalization. On the 5th day of ICU stay she developed a re-infarction and was treated for it. The patient was discharged the 26th day of ICU stay.

Methods

Routine laboratory analyses (biochemistry, hematology, blood coagulation) were performed on the patient samples daily for monitoring purposes. A portion of the serum sample taken on the 7th, 8th and 9th day of ICU stay was frozen at −20°C for IgG concentration testing. Whole blood samples taken on K3EDTA were analysed upon receipt on the automated hematology analyser Sysmex XT-1800i (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). Prior to the discovery of PS, the sodium citrate tubes were sampled for routine coagulation analyses. After detection of the PS phenomenon, if whole blood on sodium citrate for blood coagulation was not sampled, we requested sampling, for comparison purposes. The platelet count obtained with sodium citrate on the hematology analyser was multiplied by 1.1 (dilution factor). Blood smears were stained manually, using the May-Grunwald-Giemsa (MGG) stain. Blood smears were studied using light microscopy and the degree of PS was estimated (PMN involved in PS per 100 counted PMN) (6). IgG concentration was determined on the Olympus AU2700 automated chemistry analyser (Olympus corporation, Shizuoka, Japan) at the University Department of Chemistry, Medical School University Hospital Sestre Milosrdnice, Zagreb.

Results

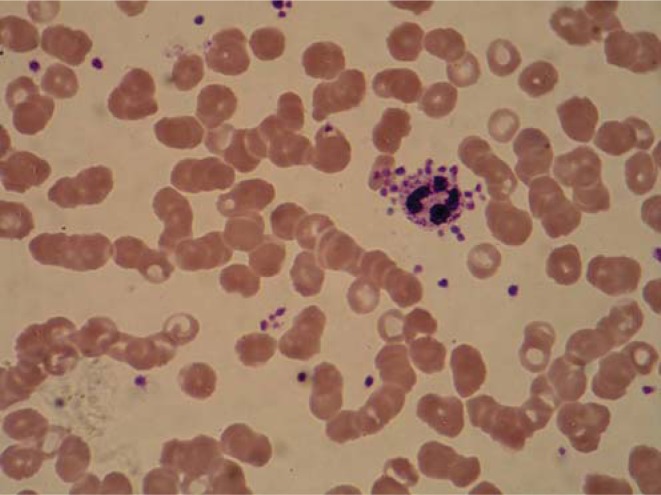

The hematological findings displayed through the patient stay in the ICU are in accordance with the patients pathological condition (Table 1). On the first and 5th day of ICU stay, complete blood count and smear analysis were requested, and no thrombocytopenia nor satellitism were noticed. However, during a requested blood smear analysis on her 7th day of ICU stay, we accidentally discovered the phenomenon of PS. The blood cell count with differential cell count performed on the automated hematology analyser, and in particular the platelet count, indicated no peculiarities and the analyser gave no warning signals (flags). It is after performing the blood smear analysis by light microscope, that we noticed the PS. Most of the PMN were surrounded by platelets, leaned onto their membranes (Figure 1). The satellitism was limited to blood samples anticoagulated with K3EDTA, because blood smears made from blood anticoagulated with sodium citrate showed absence of platelet satellitism. Also, the platelets seemed to adhere exclusively on PMN neutrophils.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings during the patient ICU stay

| Day 1 | Day 7 | Day 8 | Day 9 | Day 11 | Reference range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC (1012/L) | 4.13 | 4.16 | 4.21 | 4.09 | 3.85 | 3.86–5.08 |

| MCV (fL) | 86.2 | 85.1 | 86.5 | 87.8 | 87.5 | 83.0–97.2 |

| MCH (pg) | 26.9 | 27.4 | 27.1 | 27.1 | 27.3 | 27.4–33.9 |

| HGB (g/L) | 111 | 114 | 114 | 111 | 105 | 119–157 |

| PLT K3EDTA (109/L) | 259 | 286 | 342 | 369 | 391 | 158–424 |

| PLT Na citrate (109/L) | - | 330 | 369 | - | - | |

| MPV (fL) | 10.4 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 6.8–10.4 |

| WBC (109/L) | 17.4 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 13.6 | 14.8 | 3.4–9.7 |

| PMN (109/L) | - | 10.42 | 10.38 | - | - | 2.06–6.49 |

| IgG (g/L) | - | 4.99 | 4.79 | 5.21 | - | 7–16 |

| Degree of PS (%) | - | 62 | 15 | - | - | - |

RBC - red blood cells; MCV - mean corpuscular volume; MCH - mean corpuscular hemoglobin; HGB – hemoglobin; PLT – platelets; K3EDTA – potassium-3-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; MPV - mean platelet volume; WBC - white blood cells; PMN - polymorphonuclear neutrophils; PS -platelet satellitism.

Figure 1.

Platelet satellitism in EDTA anticoagulated blood.

The next day (8th day of ICU stay) PS was still present, but was visibly reduced and still absent in smears from blood anticoagulated with sodium citrate. On the 9th day of ICU stay and during the remaining period of the patient stay in the ICU, the PS phenomenon was no longer present in the blood smear.

Interestingly, although PS has been reported as a cause of pseudothrombocytopenia, in our case the platelet count showed no important change in terms of thrombocytopenia even on day 7 of ICU stay, when the PS was most pronounced. The platelet count observed on the 7th and 8th day of ICU stay was lower in specimens collected on K3EDTA in comparison to specimens collected on citrate due to the present PS (Table 1).

The transient nature of the PS observed in our case unfortunately did not allow any further investigation of the phenomenon.

Discussion

Platelet satellitism (PS) was first reported in 1963 by Field and McLeod and to date about a 100 cases have been reported (5,6). PS is defined as an in vitro phenomenon of platelets rosetting around neutrophils, occuring in blood samples anticoagulated only with K3EDTA at room temperature. With few exceptions, it occurs mainly with PMN (7–10). In agreement with previously published data, we found PS only around PMN and only in samples anticoagulated with K3EDTA.

PS has been observed in normal individuals and in association with a variety of disease conditions, so it is independent from pathologic processes that brought the patient to the hospital (6,8).

The pathophysiological nature of PS still remains to be elucidated, although some possible mechanisms have been reported. Published data indicate that PS activity is easily transferred by incubating PS-patient EDTA-plasma or serum, with EDTA anti-coagulated blood from subjects with no PS. Furthermore, PS activity in plasma can be annulled by prior incubation with anti-IgG serum, but not with anti-IgM or anti-IgA. In addition, the PS phenomenon can be reproduced if IgG-containing eluate after chromatographic immunopurification is incubated with normal subject samples. This demonstrates that PS is mediated by an IgG antibody and that the presence of EDTA is essential (6,11). Bizzaro et al. showed that, by incubating the PS patient sample with monoclonal antibodies anti-FcγRIII (CD16) and anti-glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, the occurence of PS can be completely blocked. They demonstrated also that no PS can be detected when PS-plasma was incubated with blood from subjects with type I Glanzmann thrombastenia (platelets lack glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex) or congenital FcγRIII deficiency on neutrophils. In conclusion, their results suggest that the IgG antibodies formed in PS-subjects are directed against the platelet GP IIb/IIIa complex and the neutrophil FcγRIII (6). The working hypothesis of the PS phenomenon is that EDTA, by chelating Ca2+ ions, changes the platelet membrane and unmasks (crypto)antigenic structures on platelet GPIIb/IIIa and PMN neutrophils, and then the IgG recognises them forming a bridge between the two cells. Why PS-patients produce these IgG (auto)antibodies and what is the mechanism of their interaction with target molecules on platelet and PMN membranes, is still unclear (11,12). Some authors suggest that thrombospondin, an α-granule protein involved in intercellular interactions, could be the cytoadhesive protein essential for PS development (13). Unfortunately, we can only speculate about the mechanism of developement of PS in our case. The most probable hypothesis is the immunological route, via formation of antibodies that caused platelets to target neutrophil membranes (and vice versa). The trigger that possibly instigated the formation of antibodies could be the drug therapy or, more likely, the transfusion therapy received in the ICU. Transfusion therapy was applied on two consecutive occasions in our patient (on the 5th day a double dose) and the PS appeared two days after that. If the underlying mechanism was immunological in nature, it is possible that it was just a mild reaction that rapidly attenuated, explaining the sudden disappearance of the PS phenomenon. For complete elucidation of the PS mechanism further investigations are needed.

PS is clinically relevant as a possible cause of spurious thrombocytopenia. It is not associated with platelet dysfuction or hemorrhagic diathesis. When PS occurs, platelet counts are moderately reduced (from 50–100 × 109/L) leading to pseudothrombocytopenia or not, like in our patient. Even if on the 7th day of ICU stay the degree of PS was 62%, thrombocytopenia was not detected because the number of platelet rosetting around neutrophils varied (from 3–5 to 15–20).

Failure of recognizing PS as the cause of pseudothrombocytopenia can lead to unnecessary laboratory testing, delay of surgery and needless transfusions or bone marrow aspirations. Even though automated hematology analysers are of widespread use in clinical laboratories, they are not always reliable in reporting error flags that could instigate suspicion. However, a simple means of excluding pseudothrombocytopenia, and thus PS, in the operative setting is the simultaneous collection of blood with two anticoagulants, EDTA and citrate, and comparison of platelet counts obtained from both specimens. Furthermore, a peripheral blood smear provides definitive evidence of pseudothrombocytopenia caused by PS. Performing a blood smear from the citrate-anticoagulated blood and/or a fingertip smear will show no platelet rosseting around PMN, which is an additional confirmation of the presence of PS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Tomislav Beus, medical photographer, for photographic assistance.

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Shahab N, Evans ML. Platelet satellitism. N Eng J Med. 1998;338:591. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802263380906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters MJ, Heyderman RS, Klein NJ. Platelet satellitism. N Eng J Med. 1998;339:131–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahab N, Evans ML. Platelet satellitism. Authors reply. N Eng J Med. 1998;339:131–2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kjeldberg CR, Swanson J. Platelet satellitism. Blood. 1974;43:831–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez-Chavarria F, Vega B. Is platelet satellitism an infrequent phenomenon? Rev Biomed. 2004;15:137–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bizzaro N. Platelet satellitosis to polymorphonuclears: cytochemical, immunological, and ultrastructural characterization of eight cases. Am J Hematol. 1991;36:235–42. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830360403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cesca C, Ben-Ezra J. Riley RS. Platelet satellitism as presenting finding in mantle cell lymphoma. A case report. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115:567–70. doi: 10.1309/mmye-vavp-54lj-jj23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazo-Langner A, Piedras J, Romero-Lagarza P, Lome-Maldonado C, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Lopez-Karpovitch X. Platelet satellitism, spurious neutropenia, and cutaneous vasculitis: casual or causal association? Am J Hematolog. 2002;70:246–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morselli M, Longo G, Bonacorsi G, Potenza L, Emilia G, Torelli G. Anticoagulant pseudothrombocytopenia with platelet satellitism. Haematologica. 1999;84:655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espanol I, Muniz-Diaz E, Domingos-Claros A. Platelet satellitism to granulated lymphocytes. Haematologica. 2000;85:1322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bizzaro N, Goldschmeding R, von dem Borne AEGK. Platelet satellitism is FcγRIII (CD16) receptor-mediated. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103:740–4. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/103.6.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodensteiner D, Talley R, Rosenfeld C. Platelet satellitism: a possible mechanism. South Med J. 1987;80:459–61. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198704000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christopoulos C, Mattock C. Platelet satellitism and α granule proteins. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:788–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.9.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]