Abstract

Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM2012 (syn. MAR1468) is an aerobic, motile, Gram-negative, non-spore-forming rod that was isolated from an ineffective root nodule recovered from the roots of the annual clover Trifolium rueppellianum Fresen growing in Ethiopia. WSM2012 has a narrow, specialized host range for N2-fixation. Here we describe the features of R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2012, together with genome sequence information and annotation. The 7,180,565 bp high-quality-draft genome is arranged into 6 scaffolds of 68 contigs, contains 7,080 protein-coding genes and 86 RNA-only encoding genes, and is one of 20 rhizobial genomes sequenced as part of the DOE Joint Genome Institute 2010 Community Sequencing Program.

Keywords: root-nodule bacteria, nitrogen fixation, rhizobia, Alphaproteobacteria

Introduction

Atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) is fixed by specialized soil bacteria (root nodule bacteria or rhizobia) that form non-obligatory symbiotic relationships with legumes. The complex, highly-evolved legume symbioses involve the formation of specialized root structures (nodules) as a consequence of a tightly controlled mutual gene regulated infection process that results in substantial morphological changes in both the legume host root and infecting rhizobia [1]. When housed within root nodules, fully effective N2-fixing bacteroids (the N2-fixing form of rhizobia) can provide 100% of the nitrogen (N) requirements of the legume host by symbiotic N2-fixation.

Currently, N2-fixation provides ~40 million tonnes of nitrogen (N) annually to support global food production from ~300 million hectares of crop, forage and pasture legumes in symbioses with rhizobia [2]. The most widely cultivated of the pasture legumes is the legume genus Trifolium (clovers). This genus inhabits three distinct centers of biodiversity with approximately 28% of species in the Americas, 57% in Eurasia and 15% in Sub-Saharan Africa [3]. A smaller subset of about 30 species, almost all of Eurasian origin, are widely grown as annual and perennial species in pasture systems in Mediterranean and temperate regions [3]. Globally important commonly cultivated perennial species include T. repens (white clover), T. pratense (red clover), T. fragiferum (strawberry clover) and T. hybridum (alsike clover). Trifolium rueppellianum is an important annual self-pollinating species grown in the central African continent as a food and forage legume.

Clovers usually form N2-fixing symbiosis with the common soil bacterium Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii, and different combinations of Trifolium spp. hosts and strains of R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii can vary markedly in symbiotic compatibility [4] resulting in a broad range of symbiotic development outcomes ranging from ineffective (non-nitrogen fixing) nodulation to fully effective N2-fixing partnerships [5].

Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2012 (syn. MAR1468) has a narrow, specialized host range for N2 fixation [6] and was isolated from a nodule recovered from the roots of the annual clover T. rueppellianum growing in Ethiopia in 1963. This strain is a good representative of one of the six centers of biodiversity, Africa, and can be used to investigate the evolution and biodiversity of R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii strains [6]. Here we present a preliminary description of the general features for R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2012 together with its genome sequence and annotation.

Classification and general features

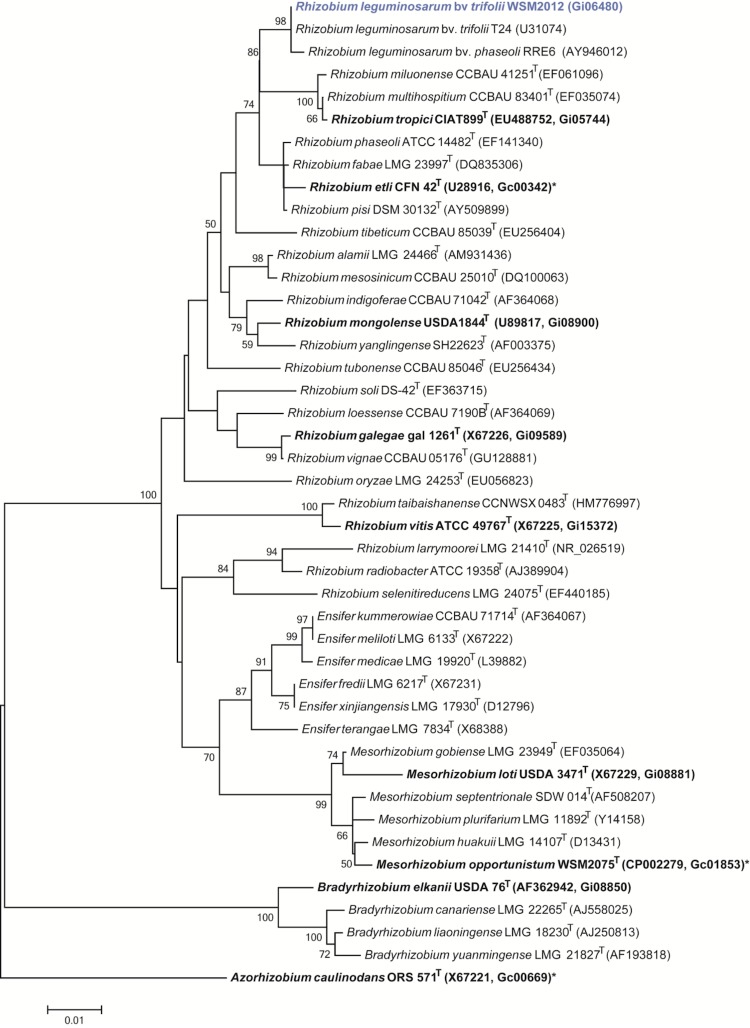

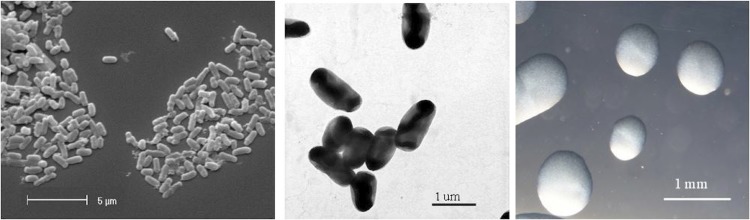

R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2012 is a motile, Gram-negative rod (Figure 1 Left and Center) in the order Rhizobiales of the class Alphaproteobacteria. It is fast growing, forming colonies within 3-4 days when grown on half Lupin Agar (½LA) [7] at 28°C. Colonies on ½LA are white-opaque, slightly domed, moderately mucoid with smooth margins (Figure 1 Right). Minimum Information about the Genome Sequence (MIGS) is provided in Table 1. Figure 2 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2012 in a 16S rRNA sequence based tree. This strain clusters closest to Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii T24 and Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. phaseoli RRE6 with 99.9% and 99.8% sequence identity, respectively.

Figure 1.

Images of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2012 using scanning (Left) and transmission (Center) electron microscopy as well as light microscopy to visualize the colony morphology on a solid medium (Right).

Table 1. Classification and general features of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM2012 according to the MIGS recommendations [8].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [9] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [10] | ||

| Class Alphaproteobacteria | TAS [11,12] | ||

| Order Rhizobiales | TAS [12,13] | ||

| Family Rhizobiaceae | TAS [14,15] | ||

| Genus Rhizobium | TAS [14,16-19] | ||

| Species Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii | TAS [14,16,19,20] | ||

| Gram stain | Negative | IDA | |

| Cell shape | Rod | IDA | |

| Motility | Motile | IDA | |

| Sporulation | Non-sporulating | NAS | |

| Temperature range | Mesophile | NAS | |

| Optimum temperature | 28°C | NAS | |

| Salinity | Non-halophile | NAS | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | NAS |

| Carbon source | Varied | IDA | |

| Energy source | Chemoorganotroph | NAS | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Soil, root nodule, on host | IDA |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living, symbiotic | IDA |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Non-pathogenic | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [21] | |

| Isolation | Root nodule | IDA | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Ethiopia | IDA |

| MIGS-5 | Nodule collection date | April 1963 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 | Longitude Latitude |

40.209961 9.215982 |

IDA |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Not recorded | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not recorded |

Evidence codes – IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [22].

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM2012 (shown in blue print) with some of the root nodule bacteria in the order Rhizobiales based on aligned sequences of the 16S rRNA gene (1,306 bp internal region). All sites were informative and there were no gap-containing sites. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA, version 5.05 [23]. The tree was built using the maximum likelihood method with the General Time Reversible model. Bootstrap analysis [24] with 500 replicates was performed to assess the support of the clusters. Type strains are indicated with a superscript T. Strains with a genome sequencing project registered in GOLD [25] are in bold print and the GOLD ID is mentioned after the accession number. Published genomes are indicated with an asterisk.

Symbiotaxonomy

R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM2012 nodulates (Nod+) and fixes N2 effectively (Fix+) with both the African annual clover T. mattirolianum Chiov. and the African perennial clovers T. cryptopodium Steud. ex A. Rich and T. usamburense Taub [6]. WSM2012 is Nod+ Fix- with the Mediterranean annual clover T. subterraneum L. and T. glanduliferum Boiss. and with both the African perennial clover T. africanum Ser. and the African annual clovers T. decorum Chiov. and T. steudneii Schweinf [1,26]. WSM2012 does not nodulate (Nod-) with the Mediterranean annual clover T. glanduliferum Prima nor the South American perennial clover T. polymorphum Poir [6].

Genome sequencing and annotation information

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its environmental and agricultural relevance to issues in global carbon cycling, alternative energy production, and biogeochemical importance, and is part of the Community Sequencing Program at the U.S. Department of Energy, Joint Genome Institute (JGI) for projects of relevance to agency missions. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes OnLine Database [25] and an improved-high-quality-draft genome sequence in IMG. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the JGI. A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information for Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2012.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Improved high-quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Illumina GAii shotgun and paired end 454 libraries |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina, 454 GS FLX Titanium technologies |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 7.4× 454 paired end, 300× Illumina |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Velvet 1.013, Newbler 2.3, phrap 4.24 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling methods | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| GOLD ID | Gi06480 | |

| NCBI project ID | 65301 | |

| Database: IMG | 2509276033 | |

| Project relevance | Symbiotic N2 fixation, agriculture |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2012 was grown to mid logarithmic phase in TY rich medium [27] on a gyratory shaker at 28°C. DNA was isolated from 60 ml of cells using a CTAB (Cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide) bacterial genomic DNA isolation method [28].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2012 was sequenced at the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) using a combination of Illumina [29] and 454 technologies [30]. An Illumina GAii shotgun library which produced 63,969,346 reads totaling 4,861.7 Mb, and a paired end 454 library with an average insert size of 8 Kb which produced 428,541 reads totaling 92.6 Mb of 454 data were generated for this genome. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at the JGI user homepage [28]. The initial draft assembly contained 158 contigs in 6 scaffolds. The 454 paired end data was assembled with Newbler, version 2.3. The Newbler consensus sequences were computationally shredded into 2 Kb overlapping fake reads (shreds). Illumina sequencing data were assembled with Velvet, version 1.0.13 [31], and the consensus sequences were computationally shredded into 1.5 Kb overlapping fake reads (shreds). The 454 Newbler consensus shreds, the Illumina VELVET consensus shreds and the read pairs in the 454 paired end library were integrated using parallel phrap, version SPS - 4.24 (High Performance Software, LLC). The software Consed [32-34] was used in the following finishing process. Illumina data were used to correct potential base errors and increase consensus quality using the software Polisher developed at JGI (Alla Lapidus, unpublished). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected using gapResolution (Cliff Han, unpublished), Dupfinisher [35], or sequencing cloned bridging PCR fragments with subcloning. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, by PCR and by Bubble PCR (J-F Cheng, unpublished) primer walks. A total of 167 additional reactions were necessary to close gaps and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The estimated genome size is 6.7 Mb and the final assembly is based on 49.8 Mb of 454 draft data which provides an average 7.4× coverage of the genome and 2,010 Mb of Illumina draft data which provides an average 300× coverage of the genome.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [36] as part of the DOE-JGI Annotation pipeline [37], followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [38]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. These data sources were combined to assert a product description for each predicted protein. Non-coding genes and miscellaneous features were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [39], RNAMMer [40], Rfam [41], TMHMM [42], and SignalP [43]. Additional gene prediction analyses and functional annotation were performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG-ER) platform [44].

Genome properties

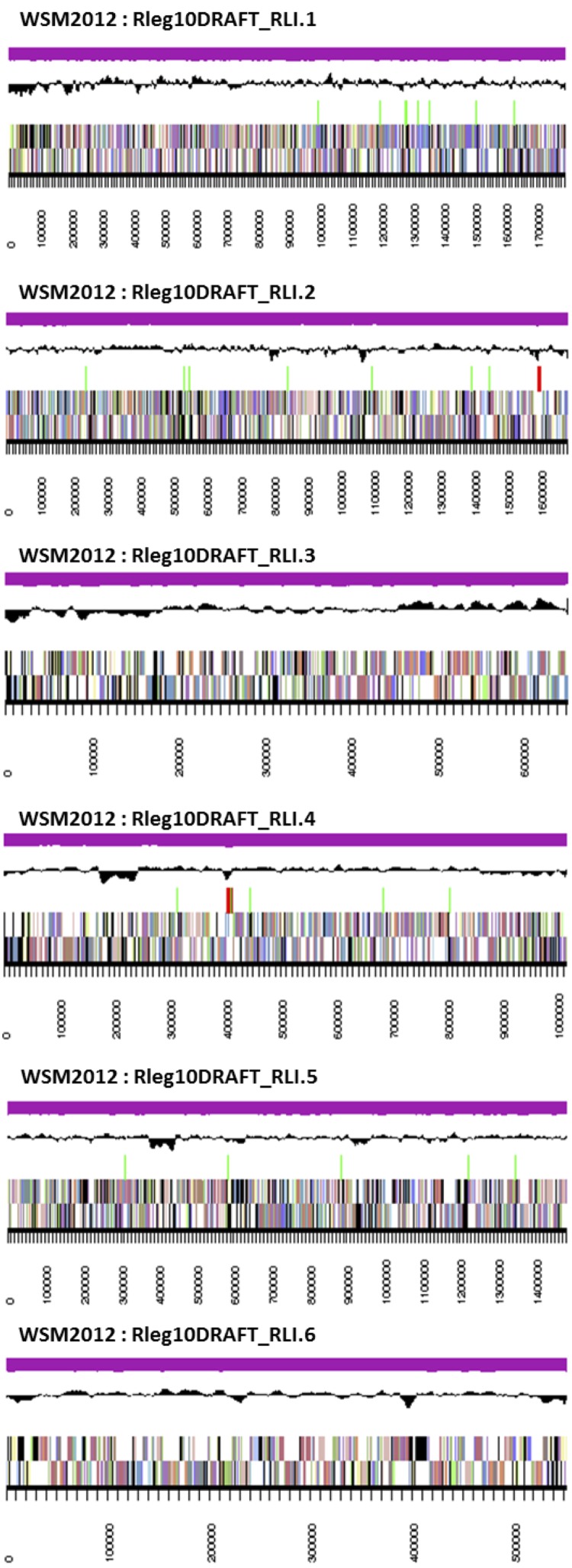

The genome is 7,180,565 nucleotides with 60.89% GC content (Table 3) and comprised of 6 scaffolds (Figure 3) of 68 contigs. From a total of 7,166 genes, 7,080 were protein encoding and 86 RNA only encoding genes. The majority of genes (72.87%) were assigned a putative function while the remaining genes were annotated as hypothetical. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics for Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM2012.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 7,180,565 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 6,196,449 | 86.29 |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 4,372,528 | 60.89 |

| Number of scaffolds | 6 | |

| Number of contigs | 68 | |

| Total gene | 7,166 | 100.00 |

| RNA genes | 86 | 1.20 |

| rRNA operons* | 3 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 7,080 | 98.80 |

| Genes with function prediction | 5,222 | 72.87 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 5,682 | 79.29 |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 5,892 | 82.22 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 615 | 8.58 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,617 | 22.56 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 |

*1 extra 5s rRNA gene

Figure 3.

Graphical map of the genome of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii strain WSM2012. From bottom to the top of each scaffold: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories as denoted by the IMG platform), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, sRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of protein coding genes of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii WSM2012 associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %age | COG Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 206 | 3.25 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0.00 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 619 | 9.76 | Transcription |

| L | 237 | 3.74 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 2 | 0.03 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 48 | 0.76 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.00 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 77 | 1.21 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 330 | 5.20 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 335 | 5.28 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 85 | 1.34 | Cell motility |

| Z | 1 | 0.02 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.00 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 108 | 1.70 | Intracellular trafficking, secretion and vesicular transport |

| O | 187 | 2.95 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 327 | 5.16 | Energy production conversion |

| G | 636 | 10.03 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 716 | 11.29 | Amino acid transport metabolism |

| F | 107 | 1.69 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 215 | 3.39 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 214 | 3.37 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 311 | 4.90 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 154 | 2.43 | Secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 802 | 12.65 | General function prediction only |

| S | 625 | 9.85 | Function unknown |

| - | 1,484 | 20.71 | Not in COGS |

Acknowledgements

This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy’s Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396. We gratefully acknowledge the funding received from the Murdoch University Strategic Research Fund through the Crop and Plant Research Institute (CaPRI) and the Centre for Rhizobium Studies (CRS) at Murdoch University. The authors would like to thank the Australia-China Joint Research Centre for Wheat Improvement (ACCWI) and SuperSeed Technologies (SST) for financially supporting Mohamed Ninawi’s PhD project.

References

- 1.Sprent JI. Legume Nodulation: A Global Perspective. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. 183 p. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herridge DF, Peoples MB, Boddey RM. Global inputs of biological nitrogen fixation in agricultural systems. Plant Soil 2008; 311:1-18 10.1007/s11104-008-9668-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamont EJ, Zoghlami A, Hamilton RS, Bennett SJ. Clovers (Trifolium L.). In: Maxted N, Bennett SJ, editors. Plant Genetic Resources of Legumes in the Mediterranean. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. p 79-98. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howieson J, Yates R, O'Hara G, Ryder M, Real D. The interactions of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii in nodulation of annual and perennial Trifolium spp. from diverse centres of origin. Aust J Exp Agric 2005; 45:199-207 10.1071/EA03167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melino VJ, Drew EA, Ballard RA, Reeve WG, Thomson G, White RG, O'Hara GW. Identifying abnormalities in symbiotic development between Trifolium spp. and Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii leading to sub-optimal and ineffective nodule phenotypes. Ann Bot (Lond) 2012; 110:1559-1572 10.1093/aob/mcs206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howieson J, Yates R, O'Hara G, Ryder M, Real D. The interactions of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii in nodulation of annual and perennial Trifolium spp. from diverse centres of origin. Aust J Exp Agric 2005; 45:199-207 10.1071/EA03167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howieson JG, Ewing MA, D'antuono MF. Selection for acid tolerance in Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Soil 1988; 105:179-188 10.1007/BF02376781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen M, Angiuoli SV and others. Towards a richer description of our complete collection of genomes and metagenomes "Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence " (MIGS) specification. 2008;26:541-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class I. Alphaproteobacteria class. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Kreig NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Second ed: New York: Springer - Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Validation List No 107. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuykendall LD. Order VI. Rhizobiales ord.nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Kreig NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Second ed: New York: Springer - Verlag; 2005. p 324. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conn HJ. Taxonomic relationships of certain non-sporeforming rods in soil. J Bacteriol 1938; 36:320-321 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank B. Über die Pilzsymbiose der Leguminosen. Ber Dtsch Bot Ges 1889; 7:332-346 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan DC, Allen ON. Genus I. Rhizobium Frank 1889, 338; Nom. gen. cons. Opin. 34, Jud. Comm. 1970, 11. In: Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE (eds), Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, Eighth Edition, The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1974, p. 262-264. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young JM, Kuykendall LD, Martínez-Romero E, Kerr A, Sawada H. A revision of Rhizobium Frank 1889, with an emended description of the genus, and the inclusion of all species of Agrobacterium Conn 1942 and Allorhizobium undicola de Lajudie et al. 1998 as new combinations: Rhizobium radiobacter, R. rhizogenes, R. rubi, R. undicola and R. vitis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2001; 51:89-103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Editorial Secretary (for the Judicial Commission of the International Committee on Nomenclature of Bacteria). OPINION 34: Conservation of the Generic Name Rhizobium Frank 1889. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1970; 20:11-12 10.1099/00207713-20-1-11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramírez-Bahena MH, García-Fraile P, Peix A, Valverde A, Rivas R, Igual JM, Mateos PF, Martínez-Molina E, Velázquez E. Revision of the taxonomic status of the species Rhizobium leguminosarum (Frank 1879) Frank 1889AL, Rhizobium phaseoli Dangeard 1926AL and Rhizobium trifolii Dangeard 1926AL. R. trifolii is a later synonym of R. leguminosarum. Reclassification of the strain R. leguminosarum DSM 30132 (=NCIMB 11478) as Rhizobium pisi sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:2484-2490 10.1099/ijs.0.65621-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agents B. Technical rules for biological agents. TRBA (http://www.baua.de):466.

- 22.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using Maximum Likelihood, evolutionary distance, and Maximum Parismony methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011; 28:2731-2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985; 39:783-791 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2007: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:D475-D479 10.1093/nar/gkm884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Hara G, Yates R, Howieson J. Selection of Strains of Root Nodule Bacteria to Improve Inoculant Performance and Increase Legume Productivity in Stressful Environments. In: Herridge D, editor. Inoculants and Nitrogen Fixation of Legumes in Vietnam. ACIAR Proceedings; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeve WG, Tiwari RP, Worsley PS, Dilworth MJ, Glenn AR, Howieson JG. Constructs for insertional mutagenesis, transcriptional signal localization and gene regulation studies in root nodule and other bacteria. Microbiology 1999; 145:1307-1316 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DOE Joint Genome Institute http://my.jgi.doe.gov/general/index.html

- 29.Bennett S. Solexa Ltd. Pharmacogenomics 2004; 5:433-438 10.1517/14622416.5.4.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA, Berka J, Braverman MS, Chen YJ, Chen Z, et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 2005; 437:376-380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zerbino DR. Using the Velvet de novo assembler for short-read sequencing technologies. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 2010;Chapter 11:Unit 11 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res 1998; 8:186-194 10.1101/gr.8.3.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl MC, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res 1998; 8:175-185 10.1101/gr.8.3.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon D, Abajian C, Green P. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res 1998; 8:195-202 10.1101/gr.8.3.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han C, Chain P. Finishing repeat regions automatically with Dupfinisher. In Proceeding of the 2006 international conference on bioinformatics & computational biology. In: Valafar HRAH, editor: CSREA Press; 2006. p 141-146. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IM, Szeto E, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The DOE-JGI Standard operating procedure for the annotations of microbial genomes. Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:63-67 10.4056/sigs.632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pati A, Ivanova NN, Mikhailova N, Ovchinnikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: a gene prediction improvement pipeline for prokaryotic genomes. Nat Methods 2010; 7:455-457 10.1038/nmeth.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffiths-Jones S, Bateman A, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res 2003; 31:439-441 10.1093/nar/gkg006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 2001; 305:567-580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol 2004; 340:783-795 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IM, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]