Abstract

Background and purpose

Some patients have persistent symptoms after total hip arthroplsty (THA). We investigated whether the proportions of inferior clinical results after total hip arthroplasty—according to the 5 dimensions in the EQ-5D form, and pain and satisfaction according to a visual analog scale (VAS)—are the same in immigrants to Sweden as observed in those born in Sweden.

Methods

Records of total hip arthroplasties performed between 1992 and 2007 were retrieved from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (SHAR) and cross-matched with data from the National Board of Health and Welfare and also Statistics, Sweden. 18,791 operations (1,451 in immigrants, 7.7%) were eligible for analysis. Logistic and linear regression models including age, sex, diagnosis, type of fixation, comorbidity, surgical approach, marital status, and education level were analyzed. Outcomes were the 5 dimensions in EQ-5D, EQ-VAS, VAS pain, and VAS satisfaction. Preoperative data and data from 1 year postoperatively were studied.

Results

Preoperatively (and after inclusion of covariates in the regression models), all immigrant groups had more negative interference concerning self-care. Immigrants from the Nordic countries outside Sweden and Europe tended to have more problems with their usual activities and patients from Europe and outside Europe more often reported problems with anxiety/depression. Patients born abroad showed an overall tendency to report more pain on the VAS than patients born in Sweden.

After the operation, the immigrant groups reported more problems in all the EQ-5D dimensions. After adjustment for covariates including the preoperative baseline value, most of these differences remained except for pain/discomfort and—concerning immigrants from the Nordic countries—also anxiety/depression. After the operation, pain according to VAS had decreased substantially in all groups. The immigrant groups indicated more pain than those born in Sweden, both before and after adjustment for covariates.

Conclusion

The frequency of patients who reported moderate to severe problems, both before and 1 year after the operation, differed for most of the dimensions in EQ-5D between patients born in Sweden and those born outside Sweden.

Some patients have persistent symptoms after total hip arthroplasty and are not satisfied with the procedure, with variation from a few up to as much as 30% (Greenwald 1991, Anakwe et al. 2011). In a Swedish nationwide prospective observational study, 5% of patients reported a clinically meaningful reduction in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and EQ-5D (Rolfson et al. 2011). The outcome of THA surgery may depend on several factors such as the type and severity of the hip disease itself, patient selection, choice of implant, the quality of the surgery, and postoperative rehabilitation. Patient-related factors including ethnicity, cultural and socioeconomic background, educational level, and expectations regarding the procedure are also important (Hawker 2006, Francis et al. 2009, Krupic et al. 2013). Several studies have compared HRQoL between racial/ethnic groups and have documented important disparities, especially related to the experience and management of pain (Tamayo-Sarver et al. 2004, Ezenwa et al. 2006). Chronic pain adversely affects the HRQoL status of black Americans to a greater extent than it affects the HRQoL status of white Americans (Green et al. 2003).

Patient-related factors have gained increased acceptance in assessment of the outcome of THA surgery. The Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (SHAR) assesses patient satisfaction, pain relief, and HRQoL using the EuroQol System (EQ-5D) (EuroQol 1990, Burstrom et al. 2001, Eisler et al. 2002, Herberts et al. 2004, Garellick et al. 2008, Rolfson et al. 2009). Understanding preoperative information about a THA may be more difficult if the patient is not sufficiently familiar with the language of the country, due to his/her immigrant status. We used the patient-reported outcomes in the SHAR to examine the hypothesis that patients who live in Sweden but have been born outside the country report worse outcome in the EQ-5D score both before and 1 year after hip replacement surgery.

Patients and methods

All THAs recorded in the SHAR between 1992 and 2007 were initially included. In Sweden, recording of PRO data was initiated in 2002 and it was gradually expanded to embrace all hospitals performing THA. Data on the 1-year follow-up until 2008 were included in this study.

Sources of data

The SHAR was started in 1979 (Herberts et al. 1990). All public and private orthopedic units in Sweden that perform hip arthroplasties participate. Apart from the information included in the social security number (date of birth and sex), individual data on age, sex, diagnosis, and side, and detailed information on implants and fixation are reported. In recent years, the individual procedure registration (completeness) has varied between 97% and 99% of all primary procedures (Garellick et al. 2008). The personal identification number enables cross-matching with other official Swedish registries. In this study, cross-matching was done with Statistics Sweden and the National Patient Register (PAR). After linkage, all further analyses were done using de-identified data. The matching of SHAR data with data from Statistics Sweden and PAR was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Gothenburg (Dnr.328-08, approved 2008-11-04).

The PROM protocol comprised the HRQoL measure EQ-5D (EuroQol Group), a VAS for pain, a Charnley classification survey (A + B, C) (Callaghan et al 1990), and a VAS addressing satisfaction after surgery (Callaghan et al. 1990, Rolfson et al. 2011). Patients were contacted preoperatively in the clinic and by post 1 year postoperatively to complete the surveys. The questionnaire has been adapted to an internet-based touch-screen application for preoperative use in hospital clinics.

The patient chooses from 3 levels that define each dimension: no problems, some or moderate problems, and extreme problems. The British tariff was used to score the EQ-5D index in this population.

The form used includes 2 visual analog scales on the preoperative form and 3 scales on the follow-up protocols. A vertical visual analog scale is used to assess the patient’s subjective rating of his/her overall health state on a scale from 0 to the best possible rating of 100 (EQ-VAS). 2 horizontal visual analog scales, 1 for pain and 1 for satisfaction (only at follow-up examinations) are similar to that of the EQ-VAS, with possible scores from 0 to 100. A score of 0 on the VAS pain scale corresponds to no pain. Similarly, complete satisfaction with the outcome earns a rating of 100 on the satisfaction VAS. To determine patient-reported comorbidity status, each patient completed the Charnley classification survey.

During recent years, the PROM program in Sweden has had a response rate of 86% preoperatively and 90% one year postoperatively (Rolfson et al. 2011). In our analysis including data collected between 2002 and 2008, the relative proportion of patients who had completed both the preoperative form and the 1-year form increased from 11% to 55%. During the entire period, the corresponding proportion was 31% (31% of those born in Sweden and 28% of those born outside Sweden).

Study population

The database covered 191,656 primary THAs recorded in the SHAR with operation dates between 1992 and 2007. All THAs from the SHAR with a complete preoperative and 1-year postoperative follow-up PROM protocol up to December 2008 were selected. The second hip operation in bilateral cases was excluded and tumor cases were excluded. We included only cases operated though a posterior or direct lateral approach with the patient on the side or supine, and without trochanteric osteotomy (99% of cases with complete PROs (patient reported measures data). We also decided to exclude patients with 1 Swedish parent and 1 non-Swedish parent and patients born abroad with 2 Swedish parents. Thus, only patients born in Sweden with 2 Swedish parents and patients born abroad with 2 parents who were also born abroad were included. After these exclusions, 18,791 THAs remained for analysis.

Data from Statistics Sweden were used to obtain information about country of birth, educational level, and cohabitation. Based on the number of patients classified as immigrants, we identified 4 groups based on birth location. These were Swedish patients (n = 17,340), patients from the other Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, and Norway, n = 819), patients from Europe excluding the Scandinavian countries and the previous Soviet region (n = 523), and patients born outside Europe or in the previous Soviet region (n = 109), (Table 1). The definition of the Soviet Union corresponded to the definition used by Statistics Sweden in the year 2000.

Table 1.

Patient data

| Variables | Born in Sweden n (%) | Nordic Countries a n (%) | Europe b n (%) | Outside Europe c n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 7,407 (43) | 254 (31) | 222 (42) | 61 (56) |

| Female | 9,933 (57) | 565 (69) | 301 (58) | 48 (44) |

| Age, mean d | 68.5 | 68.0 | 66.7 | 61.3 |

| (95% CI) | (68.4–68.6) | (67.4–68.6) | (65.8–67.7) | (58.4–64.3) |

| < 60 years | 3,159 (18) | 151 (18) | 124 (24) | 52 (48) |

| ≥ 60 years | 14,181 (82) | 668 (82) | 399 (76) | 57 (52) |

| Diagnoses | ||||

| Primary OA | 15,756 (91) | 743 (91) | 475 (91) | 84 (77) |

| Secondary OA | 1,584 (9) | 76 (9) | 48 (9) | 25 (23) |

| Charnley class | ||||

| A + B | 9,638 8 (56) | 417 (51) | 245 (47) | 44 (40) |

| C | 7,701 (44) | 402 (49) | 278 (53) | 65 (60) |

| Cohabiting | ||||

| Yes | 10,746 (62) | 476 (58) | 304 (58) | 73 (67) |

| No | 6,594 (38) | 343 (42) | 219 (42) | 36 (33) |

| Education (ISCED 97) | ||||

| Low | 10,123 (58) | 505 (62) | 231 (44) | 54 (49) |

| Middle/High | 7,217 (42) | 314 (38) | 292 (56) | 55 (51) |

| Comorbidity score e | ||||

| Elixhauser 0 | 11,731 (68) | 539 (66) | 337 (64) | 72 (66) |

| Elixhauser ≥ 1 | 5,609 (32) | 280 (34) | 186 (36) | 37 (34) |

| Charlson 0 | 14,386 (83) | 656 (80) | 417 (80) | 83 (76) |

| Charlson ≥ 1 | 2,954 (17) | 163 (20) | 106 (20) | 26 (24) |

| Type of fixation | ||||

| Cemented | 14,429 (83) | 681 (83) | 402 (77) | 59 (54) |

| Uncemented, hybrid, | ||||

| reversed hybrid | 2,911 (17) | 138 (17) | 121 (23) | 50 (46) |

| Incision | ||||

| Lateral | 5,929 (34) | 356 (43) | 234 (45) | 60 (55) |

| Posterior | 11,411 (66) | 463 (57) | 289 (55) | 49 (45) |

a Excluding Sweden.

b Excluding previous Soviet Union.

c Including previous Soviet Union.

d Mean, 95% confidence interval of the mean.

e No comorbidity (0) or 1 or more comorbidities according to Elixhauser or Charlson.

Educational level was classified into 3 groups by a simplification of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) as designed by UNESCO. These 3 groups were: low (educational level 0–2), middle (educational level 3–4), and high (educational level 5–6) (http://www.unesco.org). Information about all hospital stays in Sweden is recorded in the National Patient Register, including diagnoses ICD-9 (until 1997) and ICD-10 (from 1997 to 2007). These diagnoses were used to construct 2 comorbidity measures: Charlson, and the Elixhauser comorbidity measure. Details of this have been presented previously (Charlson et al. 1987, Armitage and Van der Meulen 2010, Bjorgul et al. 2011). To maintain a reasonable variability also within the immigrant groups, patients were classified into 2 groups, one without and the second with 1 or several comorbidities (Table 1).

Statistics

To determine whether any of the 5 subcategories in the EQ-5D form (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) could discriminate between patients born in Sweden and immigrants, the answers were dichotomized into either no problems or moderate/severe problems for each of the 5 subcategories. Any differences between the patients born in Sweden and the immigrant groups were tested using a non-parametric test (chi-square). To evaluate any influence of covariates, we performed binary logistic regression analyses with use of the outcomes no problems/moderate or severe problems for each of 5 EQ-dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression).

In the logistic regression the odds ratio is calculated, which is not equal to relative risk (Case et al. 2002). The odds that a patient born in a certain region will report some problems correspond to the probability of this event occurring divided by the opposite outcome (that they will report no problems). The odds ratios we present corresponds to the odds for reporting some problems in a region outside Sweden divided by the odds for the same outcome among those born in Sweden. Values statistically significantly above 1 indicate that patients born abroad had higher probability of reporting problems and values significantly below 1 indicate that the probability of reporting problems in this group was less.

The covariates included in the model were age (< 60, ≥ 60 years of age), sex, diagnosis (primary OA, secondary OA), Charnley class (A and B, or C), education (low, middle, or high), cohabitation (yes, no), comorbidity, type of incision (lateral, posterior incision), and choice of implant fixation (cemented; or uncemented, hybrid, reversed hybrid). The item preoperative pain was not studied using regression analysis because at that time point almost all patients reported moderate/severe problems for pain/discomfort. At the 1-year follow-up and for each of the dimensions studied (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression), the preoperative value for this dimension was also entered.

We used a directed acyclic graph (DAG) to select covariates needed for an unbiased parametric estimate of the exposure (Shier and Platt 2008, Textor et al. 2011). This gave us 2 alternative models, where some of the covariates could be excluded (type of incision, choice of fixation, diagnosis, and comorbidity). These models resulted in no or minor (< 10%) changes in the odds ratios (data not shown). VAS pain, VAS satisfaction, and EQ-VAS were analyzed using ANOVA and Student’s t-test. These parameters were also analyzed in a multiple linear regression model using the covariates presented above. In this analysis, age, education, and preoperative VAS (evaluation EQ-VAS and VAS pain at 1 year) were entered as linear variables. To reduce the number of statistical tests, the 3 immigrant groups were condensed into 1, meaning that only differences between patients born in Sweden and all those defined as immigrants were studied. The appropriateness of the linear regression models was tested by examination of residual plots. The deviation from normal distribution was judged to be within acceptable limits. For completeness, EQ-5D data are presented for the 4 patient groups. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. We used SPSS versions 19.0 and 20.0.

Results

Preoperative evaluation

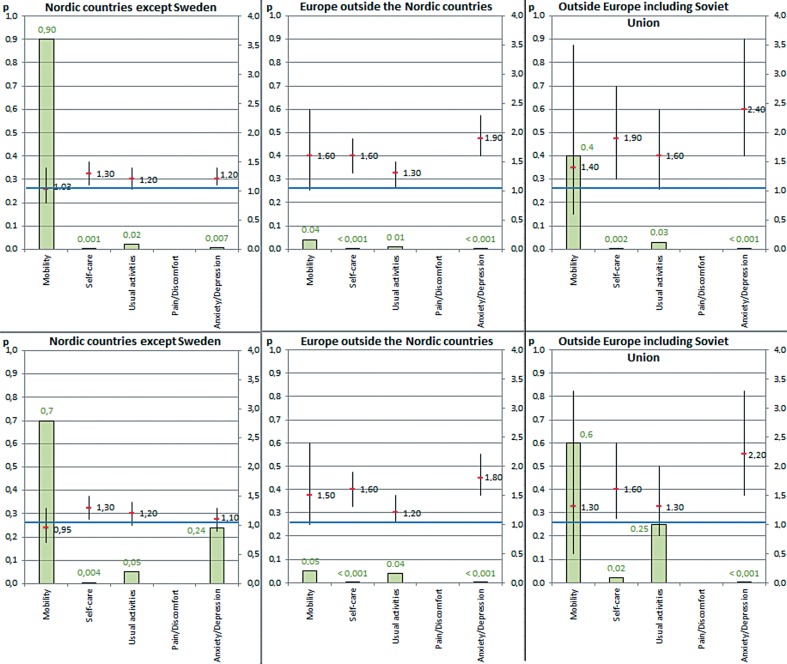

Preoperatively, almost all the patients reported problems in the domains pain and mobility. A substantial proportion also reported problems with usual activities and with anxiety/depression. In contrast, a minority reported problems with self-care (Table 2, Supplementary data). In the logistic regression model and before adjustment, patients born outside Sweden turned out to have more problems with self-care, usual activities, and anxiety/depression than patients born in Sweden. Patients born in Europe outside the Nordic countries also reported a more negative interference concerning mobility than did patients born in Sweden (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Odds ratio for reporting of moderate or severe preoperative problems in 4 of the 5 EQ5D domains. Unadjusted data (top) and adjusted data (bottom) are presented. Pain/discomfort was not analyzed because of poor variability. The risk ratios and their 95% confidence intervals are shown. Bars indicate p-values.

After inclusion of covariates in the regression model, all immigrant groups had about 30–60% increased odds ratio for having problems related to self-care. Immigrants from the Nordic countries outside Sweden and Europe tended to have more problems with their usual activities and patients from Europe and outside Europe had about doubled odds ratio for having problems related to anxiety/depression (Figure 1).

Before operation, patients born in Sweden reported less pain on the VAS scale than did those born in the Nordic countries and outside Europe (Figure 3, Supplementary data). In the linear regression model and after adjustment for covariates, patients born outside Sweden still turned out to report more pain on the VAS (regression coefficient: 1.3, 95% CI: 0.4–2.2; p = 0.005).

Preoperatively, patients born in the Nordic countries reported lower EQ-VAS than those born in Sweden. After adjustment for covariates, the preoperative EQ-VAS in the compiled group of patients born outside Sweden did not statistically significantly differ from those reported in the group born in Sweden (regression coefficient: –1.1, 95% CI: –2.2 to 0.0; p = 0.06).

Preoperatively, the baseline EQ-5D score index was lower in all immigrant groups. The lowest value was observed in patients born outside Europe, followed by immigrants from Europe outside the Nordic countries (Table 4).

Table 4.

VAS for pain and EQ-5D values preoperatively and after 1 year, and VAS for patient satisfaction after 1 year for patients born in and outside Sweden

| Preoperatively |

1 year postoperatively |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95%CI) | p-value | Mean (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Pain VAS | ||||

| Sweden | 61 (60–61) | < 0.001 a | 14 (13–14) | < 0.001 a |

| Nordic Countries | 63 (62–64) | 0.003 b | 17 (16–18) | < 0.001 b |

| Europe | 63 (61–64) | 0.05 b | 19 (18–21) | < 0.001 b |

| Outside Europe | 66 (63–69) | 0.001 b | 23 (19–26) | < 0.001 b |

| Satisfaction VAS | ||||

| Sweden | – | – | 16 (16–17) | < 0.001 a |

| Nordic countries | – | – | 19 (17–20) | 0.008b |

| Europe | – | – | 20 (18–22) | < 0.001 b |

| Outside Europe | – | – | 24 (20–28) | < 0.001 b |

| EQ-VAS | ||||

| Sweden | 53 (52–53) | 0.002 a | 75 (75–76) | < 0.001 a |

| Nordic countries | 50 (48–52) | < 0.001 b | 73 (71–74) | 0.002 b |

| Europe | 52 (49–54) | 0.2 b | 69 (67–71) | < 0.001 b |

| Outside Europe | 53 (48–58) | 0.9 b | 69 (64–73) | 0.002 b |

| EQ-5D | ||||

| Sweden | 0.40 (0.39–0.41) | < 0.001 a | 0.78 (0.77–0.78) | < 0.001 a |

| Nordic countries | 0.36 (0.34–0.38) | < 0.001 b | 0.74 (0.72–0.76) | < 0.001 b |

| Europe | 0.33 (0.30–0.36) | < 0.001 b | 0.70 (0.67–0.72) | < 0.001 b |

| Outside Europe | 0.29 (0.23–0.36) | < 0.001 b | 0.64 (0.58–0.70) | < 0.001 b |

a All groups (ANOVA).

b Born in Sweden vs. immigrant groups (Student’s t-test).

Postoperative evaluation and pain values

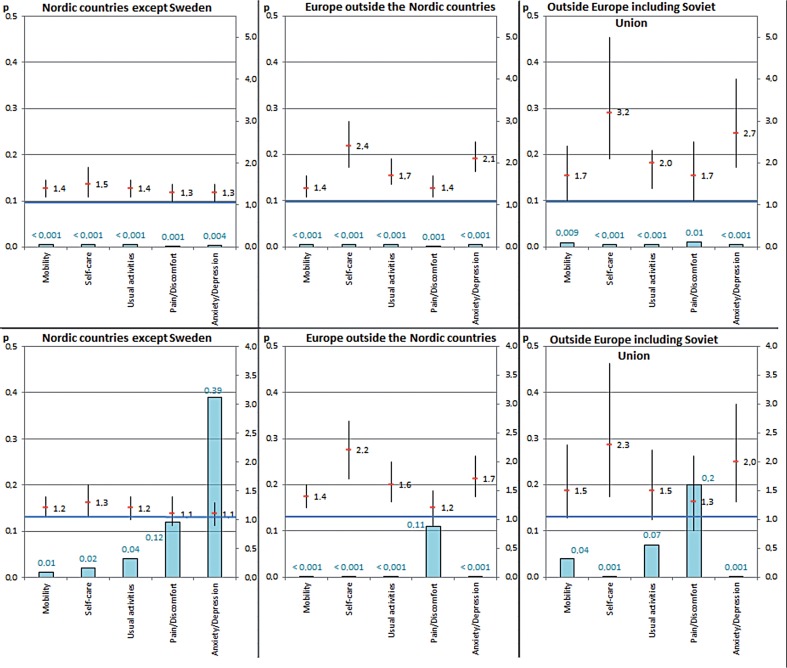

The postoperative evaluation showed that almost half of the patients or slightly more reported problems in the domains pain and mobility. A substantial proportion also reported problems with anxiety/depression and with usual activities. Problems with self-care were least commonly reported (Table 3, Supplementary data). Before adjusting for covariates, all 3 immigrant groups had an increased odds ratio for doing worse in all dimensions according to the regression analysis (Figure 2). After adjustment, the odds ratios showed an overall tendency of slight decrease. In 2 of the comparisons between patients born in Sweden and abroad (usual activities in the group born outside Europe and pain in addition to anxiety/depression in patients from the Nordic countries), the difference was not statistically significant. Thus, after adjustment for covariates, the immigrant groups—and especially those from non-Nordic parts of Europe and outside Europe—reported more problems in most of the EQ-5D dimension except for pain/discomfort, as reflected by an elevation in the odds ratios in these 2 groups, of 50% up to 130%.

Figure 2.

Odds ratio for reporting of moderate or severe problems 1 year after operation in the 5 EQ5D domains. Unadjusted data (top) and adjusted data (bottom) are presented. The risk ratios and their 95% confidence intervals are shown. Bars indicate p-values.

The pain according to VAS decreased substantially in all groups (Table 4 and Figure 3, Supplementary data). All immigrant groups indicated more pain than those born in Sweden (Table 4 and Figure 2). The multiple linear regression analysis confirmed more pain according to VAS after adjustment for covariates in patients born abroad (regression coefficient: 3.5, 95% CI: 2.5–4.4; p < 0.001).

Patients born outside Sweden were less satisfied after 1 year (Table 4). After adjustment for covariates in the regression analysis, the merged immigrant group turned out to be less satisfied (with higher VAS scores) than patients born in Sweden (regression coefficient: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.3–3.5; p < 0.001).

At 1 year postoperatively, patients born in Sweden had higher EQ-VAS than those patients born abroad. After adjustment for covariates, patients born outside Sweden reported lower quality of life in the EQ-VAS than those born in Sweden (regression coefficient: –2.8, 95% CI: –3.9 to –1.8; p < 0.001).

At 1 year, patients born in Sweden reported higher EQ-5D than the immigrant groups. The improvement (preoperatively to 1 year) was about the same for patients born in Sweden and those born outside Sweden.

Discussion

Even though the completeness of data was poor during the early phase of this study, it is probably the first nationwide study of the HRQoL after THA reported from patients born in different parts of the world. We found that before operation, patients born outside Sweden reported more problems—especially concerning self-care and anxiety/depression—than did those born in Sweden. These differences tended to remain or become slightly more pronounced 1 year after the operation. The same phenomenon was reflected by the EQ-5D and EQ-VAS before and 1 year after operation, and by the gain-values. The low baseline values in the immigrant groups and especially among those coming from outside the Nordic countries, might reflect a general unease as an immigrant in a new country. In a previous study from the Stockholm area, Burström et al. (2001) showed that HRQoL not only depended on age and sex, but also on socioeconomic status, which varied between different groups of disease. The choice between the alternatives in the EQ-5D form is subjective, and this choice may also be subject to variations related to cultural background. The use of a different tariff between countries to calculate the final EQ-5D value is one way to account for this problem. According to the statistical database Numbeo, Quality of Life for Countries 2013, the highest Quality of Life Index was observed for Switzerland (194) and the lowest for Iran (33). Quality of life for the Swedish population according to the same report was 172. This weighted index is, however, multidimensional and is based on external factors such as pollution, purchasing power, safety, and a rating of the quality of healthcare systems. These factors will certainly also influence the patient-reported opinion about their HRQoL. Thus, our study will include a certain amount of bias because the definition of what is “normal” will vary, which is certainly not the same in Sweden as in many of the countries of emigration.

Most of the patients in our study had a low educational level with a tendency of a higher proportion of middle- or high-educational level individuals in the immigrant groups. This is in accordance with our previous study, where we examined patient-reported outcomes before and 1 year after THA in the Gothenburg region (Krupic et al. 2013). Patients born outside Sweden had a higher educational level, but despite this they declared a lower income than those born in Sweden. Patients with more education may be better informed and therefore have more realistic expectations, as well as better knowledge of what is needed for their recovery. In a study of 16,000 individuals in the southeast of Sweden, Eriksson and Nordlund (2002) observed that those with the lowest level of education also reported the lowest HRQoL according to EQ-5D and SF-36. They also noted the highest level of education in persons born outside Sweden, and found that this population had a high degree of unemployment. This situation may cause anxiety, depression, nervousness, and low self-confidence—factors that will influence the experience of pain. The literature is however, not consistent concerning the influence of educational level. Mancuso et al. (2003) reported that patients with a lower level of education had higher expectations about the effectiveness of a total hip replacement concerning its ability to alleviate pain and improve walking and everyday activities.

Rolfson et al. (2009) found that preoperative anxiety/depression is a predictor of pain and patient satisfaction with the outcome 1 year after operation. Depression and anxiety are more disabling in the elderly, particularly when they co-exist with physical illness. These patients have more severe pain and more associated symptoms than non-depressed patients (Flor et al. 1992, Casten et al. 1995, Linton 1998). Pain is the main indication for THA. We found that patients born outside Sweden have more pain on the VAS both preoperatively and at 1 year postoperatively. This might be related to variation in ways of expressing feelings depending on cultural background. In some countries, it might be expected that pain and anxiety should not be apparent to relatives. In other countries, it is normal to “dress” pain and anxiety in words and show emotions (Breivik et al. 2006).

Most of the EQ-5D dimension—both preoperatively and at 1 year postoperatively—differed between patients born in Sweden and immigrants in our study. Sun et al. (2012) compared HRQoL in homeless people who had been born outside Sweden with the general population in the Stockholm area. After adjusting for covariates, the authors found a lower EQ-5D index for those originally from outside Europe than for those originally from Sweden. Preoperatively, we observed more anxiety/depression in all immigrant groups and also lower EQ-5D. The lowest EQ-5D was found in patients born outside Europe, which is consistent with the findings of Sun et al. (2012).

Our study had some limitations. The current literature usually differentiates between races, whereas our study focussed on geographical origin based on region of birth. This type of separation was partly done because no information on race was available. We also believe that the grouping performed by us is more relevant for immigrant groups in the Nordic countries and Northern Europe. Another limitation was that the immigrant groups were comparatively small—especially the one consisting of patients from outside Europe including the previous Soviet Union. This means that there was heterogeneity within the immigrant groups, most apparent in the group from outside Europe. Use of sufficiently large groups was, however, necessary to maintain sufficient statistical power.

Problems in understanding the Swedish language was another important problem with our study. This would mean that a certain proportion of the patients born abroad most probably received help from relatives or friends to fill in the questionnaire. Even if this is sometimes also the case for elderly patients born in Sweden, more immigrants can be expected to have needed assistance. Lack of knowledge of the Swedish language might also explain why the dropout rate in the immigrant group was slightly higher than in the control group. Another limitation of our study was that we used the British EQ-5D tariff, which might be better adapted to the Swedish population than to immigrants coming from some other parts of Europe and from outside Europe. Finally, the mean differences between some of the VAS parameters studied were small, and their clinical relevance could be questioned. Detailed analyses based on 5-step intervals of the visual analog scales did, however, reveal that the lowest pain scores (no or minimum pain), the highest levels of EQ-VAS, and the highest degree of satisfaction (low satisfaction VAS) was more frequently found in patients born in Sweden and the opposite outcome was more frequently observed in patients born outside Sweden (Figure 3, Supplementary data).

In conclusion, the frequency of patients who reported moderate to severe problems differed significantly for most of the dimensions in EQ-5D between patients born in Sweden and those born outside the country. This difference was observed both before and 1 year after the operation.

Supplementary data

Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 3 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 6359.

Acknowledgments

FK, JK: initiated and planned the study, preparared the database, performed statistical calculations, and wrote the manuscript. GG coordinated the database compilation and edited the manuscript. MG prepared the database, including computation of comorbidity index.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Anakwe RE, Jenkins PJ, Moran M. Predicting dissatisfaction after total hip arthroplasty: a study of 850 patients . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:209–13. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage J, Van der Meulen JH. Identifying co-morbidity in surgical patients using administrative data with the Royal College of Surgeons Charlson Score . Br J Surgery. 2010;97:772–81. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorgul K, Novicoff WM, Saleh KJ. Evaluating comorbidities in total hip and knee arthroplasty: available instruments. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;4:203–9. doi: 10.1007/s10195-010-0115-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily laif, and treatment . Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burström K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F. Health-related quality of life by disease an socio-economic group in the general population in Sweden . Health Policy. 2001;55:51–69. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan JJ, Dysart SH, Savory CF, Hpkinson WJ. Assessing the results of hip replacement. A comparison of five different rating systems . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1990;72:1008–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B6.2246281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case LD, Kimmick ED, Paskett ED, Lohman K, Tucker R. Interpreting measures of treatment effect in cancer clinical trials . Oncologist. 2002;7:181–7. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-3-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casten RJ, Parmelee PA, Kleban MH, Lawton MP, Katz IP. The relationschip among anxiety, Depression and pain in a geriatric institutionalized sample . Pain. 1995;61:271–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00185-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation . J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler T, Svensson O, Tengstrom A, Elmstedt E. Patient expectation and satisfaction in revision total hip arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:457–62. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.31245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson E, Nordlund A. Health and health related quality of life as measured by the EQ-5D and the SF-36 in South East Sweden: Results from two population surveys. 2002, Folkvetenskaplig Centrum, Linköping (In swedish)1-42. www.lio.se/fhvc

- EuroQol group, EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwa MO, Ameringer S, Ward SE, Serlin R. C. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain management in the United States . J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38:225–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk D. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic review . Pain. 1992;49:221–30. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis ML, Scaife SL, Zahnd WE, Cook EF, Schneeweiss S. Joint replacement surgeries among medicare beneficiaries in rural compared with urban areas . Arthritis Rheum. 2009;12:3554–62. doi: 10.1002/art.25004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garellick G, Kärrrholm J, Rogmark C, Herberts P. Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register, Annual Report. http://www.shpr.se 20082008

- Green CR, Baker T. A, Smith E. M, Sato Y. The effect of race in older adults presenting for chronic pain management: a comparative study of black and white Americans . J. Pain. 2003;2:82–90. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald HP. Interethnic differences in pain perception . Pain. 1991;44:157–63. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90130-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker GA. Who, when and why total joint replacement surgery? The patient’s perspective. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;5:526–30. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000240367.62583.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberts P, Ahnfelt L, Malchau H, Stromberg C, Andersson G. B. Multicenter clinical trials and their value in assessing total joint arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. 1990;249:48–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberts P, Kärrholm J, Garellick G. Swedish Hip Arthroplasty register, Annual report. http://www.shpr.se 20042004

- ISCED: International Standard Classification of Education http://www.unesco.org/education/information/nfsunesco/doc/isced_1997.htm

- Krupic F, Eisler T, Garellick G, Karrholm J. Influence of ethnicity and socioeconomic factors on outcome after total hip replacement . Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27:139–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton S, Hallden K. We can screen for problematic back pain: a screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain . Clin J Pain. 1998;3:209–15. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199809000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso CA, Sculco TP, Salvati EA. Patients with poor preoperative functional status have high expectations of total hip arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:872–8. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life for cities and countries worldwide, report February 2013 http://numbeo.com

- Rolfson O, Dahlberg LE, Nilsson JA, Malchau H, Garellick G. Variables determining outcome in total hip replacement surgery . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91:157–61. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.20765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfson O, Karrholm J, Dahlberg LE, Garellick G. Patient-reported outcomes in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register: results of a nationwide prospective observational study . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93:867–75. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B7.25737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier I, Platt R. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs . BMC Med Res Method. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Irestig R, Burström B, Beijer U, Burström K. Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D) among homeless persons compared to a general population sample in Stockholm County . Scand J Public Health. 2006;2012;40:115–25. doi: 10.1177/1403494811435493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo-Sarver JH, Hinze SW, Cydulka RK, Baker DW. Racial and ethnic disparities in emergency department analgesic prescription. Am J Public Health. 2004;12:2067–73. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Textor J, Hardt J, Knüppel S. DAGitty: A graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams . Epidemiology. 2011;22(5):745. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318225c2be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.