Abstract

Background and purpose

In 2003, an enquiry by the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR) 2–7 years after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) revealed patients who were dissatisfied with the outcome of their surgery but who had not been revised. 6 years later, we examined the dissatisfied patients in one Swedish county and a matched group of very satisfied patients.

Patients and methods

118 TKAs in 114 patients, all of whom had had their surgery between 1996 and 2001, were examined in 2009–2010. 55 patients (with 58 TKAs) had stated in 2003 that they were dissatisfied with their knees and 59 (with 60 TKAs) had stated that they were very satisfied with their knees. The patients were examined clinically and radiographically, and performed functional tests consisting of the 6-minute walk and chair-stand test. All the patients filled out a visual analog scale (VAS, 0–100 mm) regarding knee pain and also the Hospital and Anxiety and Depression scale (HAD).

Results

Mean VAS score for knee pain differed by 30 mm in favor of the very satisfied group (p < 0.001). 23 of the 55 patients in the dissatisfied group and 6 of 59 patients in the very satisfied group suffered from anxiety and/or depression (p = 0.001). Mean range of motion was 11 degrees better in the very satisfied group (p < 0.001). The groups were similar with regard to clinical examination, physical performance testing, and radiography.

Interpretation

The patients who reported poor response after TKA continued to be unhappy after 8–13 years, as demonstrated by VAS pain and HAD, despite the absence of a discernible objective reason for revision.

The results of TKA are regarded as being favorable (Robertsson et al. 2000, Kane et al. 2005, Nilsdotter et al. 2009, Carr et al. 2012) with few surgical complications and a revision rate of less than 5% after 10 years (Vessely et al. 2006, Robertsson et al. 2010). Poor outcome after primary TKA, apart from the revision, is between 6% and 14% (Anderson et al. 1996, Hawker et al. 1998, Heck et al. 1998, Robertsson et al. 2000, Robertsson and Dunbar 2001, Brander et al. 2003, Noble et al. 2006, Fisher et al. 2007, Wylde et al. 2008, Kim et al. 2009, Bourne et al. 2010, Scott et al. 2010). The reason for poor outcome after TKA may be related to problems with the knee surgery itself, although it has been suggested that extra-articular causes such as hip disease, spine disorder, vascular disease, or reflex sympathetic dystrophy may contribute. Some studies have suggested that factors not primarily related to structural tissue changes, but of psychological nature instead, may be involved (Wylde et al. 2007, Rolfson et al. 2009).

The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR) registers primary arthroplasties performed in Sweden as well as revisions, and has been estimated to capture 97% of the surgeries performed (SKAR 2012). The SKAR sends questionnaires regarding satisfaction to patients who were operated on during certain time periods (Robertsson et al. 2000, and Dunbar 2001). We used the SKAR to identify patients who had not undergone revision surgery and who were dissatisfied with their outcome 2–7 years after TKA surgery. As a reference we chose an age-, sex-, date-of-surgery-, and hospital-matched control group of highly satisfied patients who were operated during the same period. Our aim was to assess the differences between these 2 patient groups.

Patients and methods

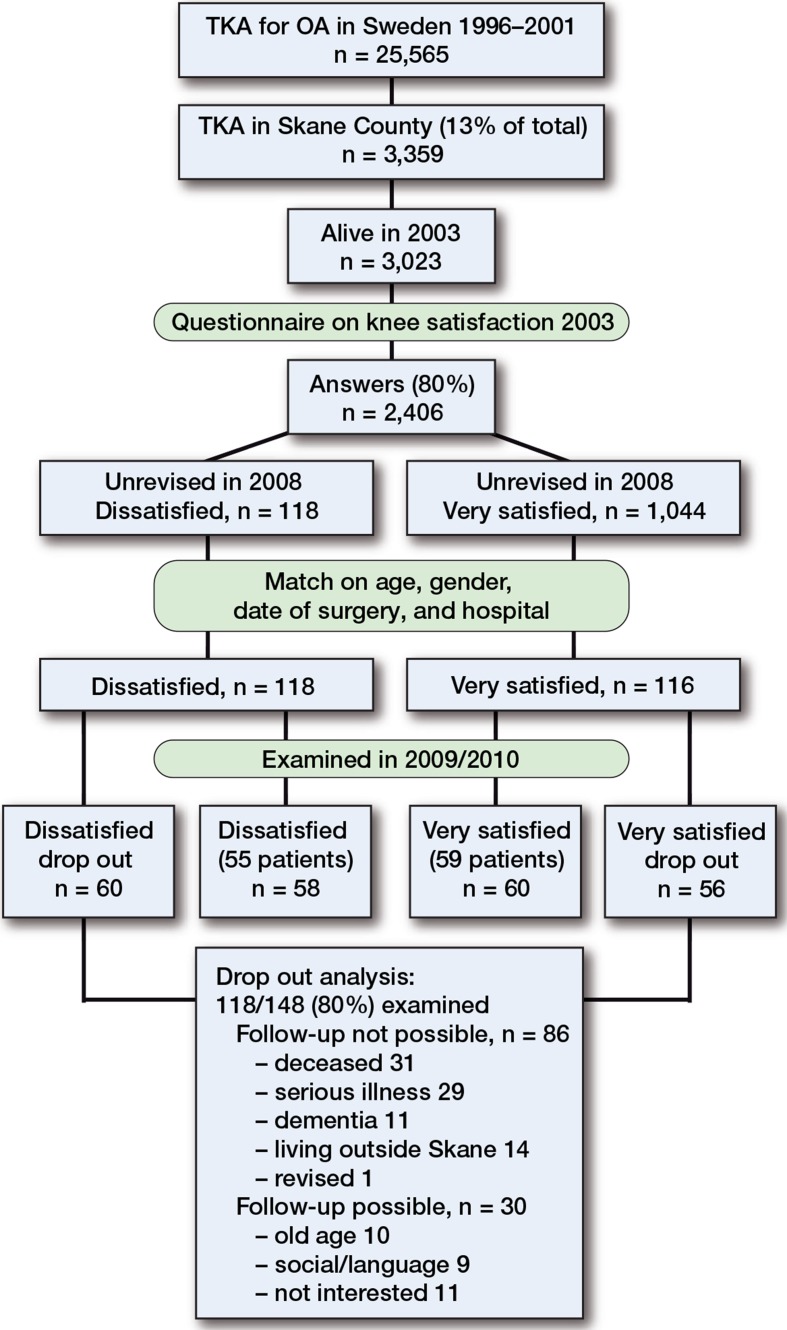

3,359 primary TKAs were performed for primary osteoarthritis (OA) in the county of Skåne (1.1 million inhabitants) between 1996 and 2001. According to the SKAR, this corresponded to 13% of all TKAs performed in Sweden (n = 25,565) during the same period (Figure). In 2003, a questionnaire was sent by the SKAR to all living TKA patients in Sweden who had been operated on during these years. The patients were asked to grade their level of satisfaction regarding the operated knee as follows: 1, very satisfied; 2, satisfied; 3, uncertain; or 4, dissatisfied (Robertsson et al. 2000) .

Flow chart of material. All numbers above are number of knees unless patients are mentioned.

114 patients in the county of Skåne (corresponding to 118 unrevised knees) were dissatisfied, and they constituted one of our study groups. This group was compared to an age-, sex-, surgery date-, and hospital-matched group of 113 patients (with 116 unrevised knees) who were very satisfied with their knee. The surgeries had been performed at 9 hospitals in Skåne.

At the start of follow-up, 6 years after receiving the questionnaire, 1 of the 234 knees had been revised. An invitation letter to attend a follow-up was sent to the remaining patients. 197 patients replied, and they were invited to a clinical and radiographic assessment. This corresponded to 202 TKAs (101 in each group). 114 patients accepted (118 TKAs), 55 patients from the dissatisfied group (58 TKAs) and 59 patients from the very satisfied group (60 TKAs). The reasons for dropout were that the patients had died, were senile or severely disabled (for reasons other than their knees), or were not able to attend/perform the follow-up. Patients who did not answer received a second letter of invitation. They were then contacted by telephone by a nurse, and thereafter by a doctor. The response rate was 80% for those who were available for follow-up (Figure).

The patients filled out the visual analog pain scale (100-mm VAS where 0 = no pain and 100 = severe pain) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HAD) (Zigmond and Snaith 1983). 2 orthopedic surgeons (AA and AL) interviewed and examined the patients independently of each other: AL interviewed the patients and AA examined the patients’ back, lower limbs regarding ROM, antero-posterior and medio-lateral knee laxity, and patella tenderness, and also supervised the 2 physical performance tests (the 6-minute walking test (6MW) (Steffen et al. 2002) and the chair-stand test (CS) (Guralnik et al. 1994) without knowing which group the patients belonged to.

The patients also underwent radiographic examinations (AP and lateral standing, patellar view, and standing long-leg). The radiographs were interpreted by 2 experienced skeletal radiologists (IR-J and IK) who were unaware of which group the patients belonged to (Table 1). 3 options were used: normal, possibly abnormal, and abnormal. The mechanical axis (HKA) was calculated from the standing long-leg radiographs. The study was approved by the ethical board of Lund University and by the radiography ethical committee of Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden (NR2009/06 & 2009-04-29/NR:0909).

Table 1.

Results of radiographic analysis

| Variables a | Dissatisfied n = 55 | Very satisfiedn = 59 | RR | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal femoral component position | 2 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.90–1.03 |

| Suboptimal tibial component position | 11 | 14 | 1.05 | 0.6 | 0.86–1.28 |

| Patella subluxation | 12 | 7 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.73–1.05 |

| Zone | 3 | 3 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.89–1.08 |

| Polyethylene wear | 2 | 3 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.17–4.03 |

| Femoropatellar osteoarthritis | 33 | 34 | 1.03 | 0.9 | 0.65–1.63 |

| Mechanical axis 0 ± 4 degree | 43 | 42 | 1.05 | 0.6 | 0.85–1.30 |

a Suboptimal outcome includes both possibly abnormal and abnormal findings.

RR: relative risk, dissatisfied vs. very satisfied.

Statistics

A Cox multiple regression analysis with constant follow-up and robust variance estimation (Barros and Hirakata 2003) was used to study relative risks (RRs) for categorical variables in the dissatisfied group. Continuous variables, e.g. the mean difference between the groups, were analyzed by ANCOVA method. In both methods, patients’ age at operation, sex, and date of operation were included. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical analysis was based on 1 knee per patient. Analyses were performed using Stata software version 12.

Results

The dissatisfied group had a higher mean VAS pain score than the very satisfied group (52 mm and 22 mm respectively; p < 0.001) (Table 2). In the HAD scale, more patients were found to have mild, moderate, or severe anxiety and/or depression in the dissatisfied group (23 of 55) than in the very satisfied group (6 of 59) (p = 0.001). The average ROM was 97 degrees in the dissatisfied group and 108 degrees in the very satisfied group (p < 0.001). The clinical examinations, performance tests, and radiographic analyses gave similar results in both groups (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Variables | Dissatisfied n = 55 | Very satisfied n = 59 | RR a | Mean diff. b | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 78 (SD 8) | 79 (SD 7) | ||||

| Gender (female) | 39 | 43 | ||||

| Mean follow-up, years | 10.5 (SD 2.5) | 10.5 (SD 2.5) | ||||

| Mean VAS score (0–100) | 52 | 22 | 31 | < 0.001 | 23 to 39 | |

| HAD c, no. patients | 23 | 6 | 4.1 | 0.001 | 2 to 9 | |

| Mean ROM, degrees | 97 | 108 | –13 | < 0.001 | –18 to –7 | |

| Mean 6MW test result, m | 295 | 318 | –35 | 0.07 | –74 to 3 | |

| Mean chair test result, s | 19 | 17 | 2.7 | 0.1 | –0.5 to 6 | |

| Mean BMI | 32 | 30 | 1.4 | 0.2 | –0.7 to 3 | |

| Smokers | 2 | 4 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.6 to 1 | |

| Increased knee laxity | 3 | 5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 to 2 | |

| Patella tenderness | 8 | 6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.2 to 4 |

aRR: relative risk, dissatisfied vs. very satisfied.

bMean difference, dissatisfied vs. very satisfied.

cAnxiety and/or depression according to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale

Discussion

In 2009–2010, we found that TKA patients who had been dissatisfied in 2003 had more knee pain, more anxiety and/or depression, and less ROM than those who had been very satisfied, but that the other clinical findings, performance tests, and radiographic results were similar.

We did not observe any TKA complications for which revision might have been indicated but not offered. Thus, we found no signs that the dissatisfied, unrevised TKA patients had neglected complications that would have indicated revision surgery, except in 1 patient with polyethylene wear diagnosed by radiography, which caused subluxation of the joint. This patient belonged to the very satisfied group but became symptomatic a short time before our follow-up.

This registry study had certain limitations due to the absence of preoperative data such as VAS, HAD, and ROM, which was the reason for using a matched control group. Most TKA studies on postoperative pain have been short-term, such as Brander et al. 2003 who found VAS pain scores exceeding 40 in 13% of TKA patients after 1 year. The mean VAS pain score in our dissatisfied group was approximately the same as VAS pain scores reported before revision of TKA (van Kempen et al. 2013). Mean VAS pain score in our very satisfied group was 22, corresponding to that reported from 1-year follow-up in the SKAR (SKAR 2012).

In the SKAR report on 27,372 knees, approximately 8% of the patients were dissatisfied. Satisfaction was higher in males, in patients with OA, and in those with long-standing disease whereas the follow-up time (2–17 years) had no influence on the degree of satisfaction (Robertsson et al. 2000). The most robust predictions concerning satisfaction with TKA were found when both pre- and postoperative data where considered together (Baker et al. 2013) .

One striking finding in our study was the high incidence of anxiety and/or depression in the dissatisfied group, and we wonder whether the dissatisfaction was the cause of the anxiety and/or depression or the result of it. Rolfson et al. (2009) reported that patients with preoperative anxiety/depression had a higher risk of becoming dissatisfied after total hip arthroplasty. Notably, Axford et al. 2010 found a similarly high incidence of depression and anxiety in unoperated knee osteoarthritis patients as we found in the dissatisfied group. In a review article, Paulsen et al. (2011) identified 10 TKA cohort studies. 6 had found a correlation between preoperative distress and functional outcome. Furthermore, Scott et al. (2010) found that depression and poor mental health had an influence on the degree of dissatisfaction in TKA-operated patients. Brander et al. (2007) also found that depression influenced outcome after TKA, and they postulated that identifying and treating depression before surgery may be important in improving the result after TKA.

The mean ROM was 97 degrees in the dissatisfied group, which could be considered suboptimal. However, it was evidently sufficient to allow these patients to perform the physical performance tests as well as the very satisfied patients. Miner et al. (2003) found that there was a correlation between knee flexion of less than 95 degrees and substantial functional impairment, and Matsuda et al. (2013) found a positive correlation between satisfaction and ROM. Kim et al. (2009) reported that decrease in postoperative ROM could lead to dissatisfaction. On the other hand, Devers et al. 2011 found no correlation between knee flexion and satisfaction.

In the present study, patients who were dissatisfied had similar clinical findings, performance tests, and radiographic findings to those who were very satisfied. The patients who had reported poor response after TKA continued to be unhappy, as demonstrated by VAS pain and HAD, despite the absence of a discernible objective reason for revision. It would be of advantage if patients who are likely to be dissatisfied with their outcome could be identified before TKA is performed.

Acknowledgments

AA, AL, MS, OR, LD, and CT conceived and designed the study and contributed to revision of the manuscript. OR identified the patients from the SKAR. AA and AL examined the patients. IR-J and IK assessed radiographs. AA collected and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

We thank Professor Lars Lidgren for all his support and advice, and Professor Jonas Ranstam for valuable advice on statistics. Financial support was kindly provided by Region Skåne and by the Erik and Angelica Sparre Foundation.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Anderson JG, Wixson RL, Tsai D, Stulberg SD, Chang RW. Functional outcome and patient satisfaction in total knee patients over the age of 75 . J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:7, 831–40. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(96)80183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axford J, Butt A, Heron C, Hammond J, Morgan J, Alavi A, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in osteoarthritis: use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool . Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:11, 1277–83. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1547-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PN, Rushton S, Jameson SS, Reed M, Gregg P, Deehan DJ. Patient satisfaction with total knee replacement cannot be predicted from pre-operative variables alone: A cohort study from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2013;95:10, 1359–65. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B10.32281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio . BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? . Clin Orthop. 2010;468(1):57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brander VA, Stulberg SD, Adams AD, Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanos SP, et al. Predicting total knee replacement pain: a prospective, observational study . Clin Orthop. 2003;416:27–36. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000092983.12414.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brander V, Gondek S, Martin E, Stulberg SD. Pain and depression influence outcome 5 years after knee replacement surgery . Clin Orthop. 2007;464:21–6. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318126c032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr AJ, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price AJ, Arden NK, Judge A, et al. Knee replacement. Lancet. 2012;379:9823, 1331–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60752-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devers BN, Conditt MA, Jamieson ML, Driscoll MD, Noble PC, Parsley BS. Does greater knee flexion increase patient function and satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty? . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:2, 178–86. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DA, Dierckman B, Watts MR, Davis K. Looks good but feels bad: factors that contribute to poor results after total knee arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty (Suppl 2) 2007;22:6, 39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission . J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker G, Wright J, Coyte P, Paul J, Dittus R, Croxford R, et al. Health-related quality of life after knee replacement . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1998;80:2, 163–73. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199802000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck DA, Melfi CA, Mamlin LA, Katz BP, Arthur DS, Dittus RS, et al. Revision rates after knee replacement in the United States . Med Care. 1998;36:5, 661–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RL, Saleh KJ, Wilt TJ, Bershadsky B. The functional outcomes of total knee arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87:8, 1719–24. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TK, Chang CB, Kang YG, Kim SJ, Seong SC. Causes and predictors of patient’s dissatisfaction after uncomplicated total knee arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:2, 263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S, Kawahara S, Okazaki K, Tashiro Y, Iwamoto Y. Postoperative Alignment and ROM Affect Patient Satisfaction After TKA . Clin Orthop. 2013;471(1):127–33. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2533-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner AL, Lingard EA, Wright EA, Sledge CB, Katz JN. Knee range of motion after total knee arthroplasty: how important is this as an outcome measure? . J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:3, 286–94. doi: 10.1054/arth.2003.50046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsdotter AK, Toksvig-Larsen S, Roos EM. A 5 year prospective study of patient-relevant outcomes after total knee replacement . Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(5):601–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble PC, Conditt MA, Cook KF, Mathis KB. The John Insall Award: Patient expectations affect satisfaction with total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2006;452:35–43. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238825.63648.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen MG, Dowsey MM, Castle D, Choong PF. Preoperative psychological distress and functional outcome after knee replacement . ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:10, 681–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Dunbar MJ. Patient satisfaction compared with general health and disease-specific questionnaires in knee arthroplasty patients . J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:4, 476–82. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.22395a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Dunbar M, Pehrsson T, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Patient satisfaction after knee arthroplasty: a report on 27,372 knees operated on between 1981 and 1995 in Sweden . Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(3):262–7. doi: 10.1080/000164700317411852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Bizjajeva S, Fenstad AM, Furnes O, Lidgren L, Mehnert F, et al. Knee arthroplasty in Denmark, Norway and Sweden . Acta Orthop. 2010;81:1, 82–9. doi: 10.3109/17453671003685442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfson O, Dahlberg LE, Nilsson JA, Malchau H, Garellick G. Variables determining outcome in total hip replacement surgery . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91(2):157–61. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.20765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CE, Howie CR, MacDonald D, Biant LC. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a prospective study of 1217 patients . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92:9, 1253–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.24394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKAR Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register: Annual report 2012 Lund University Hospital, Lund; 2012. 2012. http://www.knee.se/]

- Steffen TM, Hacker TA, Mollinger L. Age- and gender-related test performance in community-dwelling elderly people: Six-Minute Walk Test, Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up & Go Test, and gait speeds. Phys Ther. 2002;82:2, 128–37. doi: 10.1093/ptj/82.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen RW, Schimmel JJ, van Hellemondt GG, Vandenneucker H, Wymenga AB. Reason for revision TKA predicts clinical outcome: prospective evaluation of 150 consecutive patients with 2-years followup . Clin Orthop. 2013;471(7):2296–302. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2940-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessely MB, Whaley AL, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Berry DJ. The Chitranjan Ranawat Award: Long-term survivorship and failure modes of 1000 cemented condylar total knee arthroplasties . Clin Orthop. 2006;452:28–34. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229356.81749.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylde V, Dieppe P, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID. Total knee replacement: is it really an effective procedure for all? . Knee. 2007;14:6, 417–23. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylde V, Learmonth I, Potter A, Bettinson K, Lingard E. Patient-reported outcomes after fixed- versus mobile-bearing total knee replacement: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial using the Kinemax total knee replacement . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008;90:9, 1172–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B9.21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale . Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:6, 361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]