Abstract

Background and purpose

The incidence and annual number of hip fractures have increased worldwide during the past 50 years, and projections have indicated a further increase. During the last decade, however, a down-turn in the incidence of hip fracture has been seen in the western world. We predicted the development of hip fractures in Sweden until the year 2050.

Methods

We reviewed surgical records for the period 2002–2012 in the city of Malmö, Sweden, and identified patients aged 50 years or more with a hip fracture. We estimated incidence rates by using official population figures as denominator and applied the rates to population projections each year until 2050. We also made projections based on our previously published nationwide Swedish hip fracture rates for the period 1987–2002. Since the projections are based on estimates, no confidence limits are given.

Results

During the period 2002–2012, there were 7,385 hip fractures in Malmö. Based on these data, we predicted that there would be approximately 30,000 hip fractures in Sweden in the year 2050. Use of nationwide rates for 2002 in the predictive model gave similar results, which correspond to an increase in the number of hip fractures by a factor of 1.9 (1.7 for women and 2.3 for men) compared to 2002.

Interpretation

The annual number of hip fractures will almost double during the first half of the century. Time trends in hip fractures and also changes in population size and age distribution should be continuously monitored, as such changes will influence the number of hip fractures in the future. Our results indicate that we must optimize preventive measures for hip fractures and prepare for major demands in resources.

Hip fracture rates increased worldwide during the last half of the twentieth century, and several projections suggested that the increase would continue (Cooper et al. 1992, Gullberg et al. 1997, Kannus et al. 1999). During the past decade, however, a break in the trend has been seen in many parts of the world, with stable—or even decreasing—hip fracture rates (Kannus et al. 2006, Dhanwal et al. 2011, Rosengren et al. 2012). The many studies highlighting this down-turn have not been followed by an equal interest in new projections on the future number of hip fractures. Sweden, a country that is highly burdened by fragility fractures, with a progressively increasing life expectancy and proportion of elderly, is of special interest. We therefore updated hip fracture projections for Sweden using recent local incidence rates, detailed nationwide rates, and up-to-date population projections.

Subjects and methods

The city of Malmö is located in the southernmost part of Sweden. The inhabitants represent a Swedish rural population with a mean age of 39 years (in 2012), which is similar to that of the capital city of Stockholm but lower than the mean age in Sweden as a whole (41 years) (Stadskontoret Malmö 2013). The population in and around Malmö is multicultural, with 22% immigrants. This proportion is similar to that in Stockholm but higher than that in Sweden overall (15%) (Statistics Sweden 2013).

We manually reviewed the digital surgical records of Skåne University Hospital in the City of Malmö (with a total catchment population (all ages) of 403,949 in 2012) for the period 2002-2012 and included all individuals aged ≥ 50 years who had undergone primary surgery for hip fracture (cervical, trochanteric, and sub-trochanteric fractures). Those who resided outside the catchment area were excluded. Sex-specific population figures in 1-year age classes for the catchment area in the age stratum ≥ 50 years during the examination period were obtained from Statistics Sweden and used as denominator to estimate rates in different sex and age-specific strata. We then applied the rates to official annual population projections from Statistics Sweden for each year until year 2050.

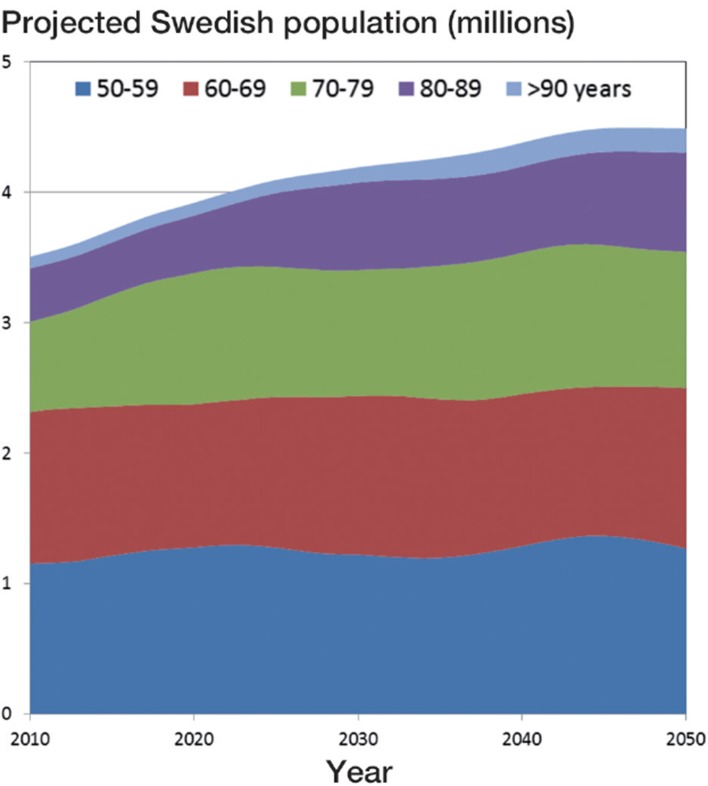

Hip fracture incidence rates for individuals aged ≥ 50 years in Sweden during the period 1987–2002 (Table) have been described in detail previously, together with the method for data extraction from the official Swedish Inpatient Records (Rosengren et al. 2012). In that study, a breakpoint was evident around 1996. Before that year, the hip fracture rate was stable and the annual numbers were increasing, but after that both the annual rate and the numbers decreased, with approximately 16,000 new hip fractures in Sweden in 2002 (Rosengren et al. 2012). Using these data, we made projections of the annual number of hip fractures in Sweden in men and women aged ≥ 50 years, until the year 2050. We used 2 models based on (i) sex-specific incidence rates in 1-year age strata from data from 2002, and (ii) sex-specific incidence rates in 1-year age strata for the overall period from 1987 to 2002, to disperse annual fluctuations. We also decided to make a presumably unrealistic but didactic projection (iii) using low-resolution data with sex-specific (but not age-specific) incidence rates for the overall period 1987–2002 in the aggregated age stratum ≥ 50 years (thereby deliberately not taking into account shifts in the age distribution within the population) to highlight the importance of detailed data. Annual sex- and 1-year age-class-specific population projection figures in individuals aged ≥ 50 years were obtained from Statistics Sweden until the year 2050, with major shifts in population size and age distribution (Figure 1). The projected number of hip fractures from each model was compared to the number from the most recent year of actual nationwide data (2002). The progression of annual numbers during the projected period was estimated by simple regression.

Gender-specific hip fracture incidence rates per 10,000 individuals according to different studies (Gullberg et al. 1993, Hedlund et al. 1987, Lofman et al. 2002, Rogmark et al. 1999, Rosengren et al. 2012, Nilson et al. 2013) in different settings and time frames in Sweden during the period 1950–2012

| Age | Gullberg et al. Malmö |

Hedlunda Stockholm | Löfmana Östergötland | Rogmark Malmö | Rosengren Sweden |

Present study Malmö | Age | Nilson Sweden |

Present study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950-1958 | 1967-1975 | 1980-1985 | 1987-1991 | 1972-1981 | 1982-1996 | 1992-1995 | 1987-2002 | 2002 | 2002-2012 | 1987 | 1997 | 2009 | 2002-2012 | ||

| Women | |||||||||||||||

| 50–54 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 3.8 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |||||

| 55–59 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 8 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 4 | |||||

| 60–64 | 19 | 17 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 16 | 19 | 14 | 9 | 11 | |||||

| 65–69 | 30 | 25 | 26 | 33 | 29 | 26 | 24 | 26 | 22 | 22 | 65–79 | 91 | 88 | 58 | 50 |

| 70–74 | 48 | 48 | 54 | 61 | 57 | 53 | 52 | 53 | 49 | 39 | |||||

| 75–79 | 76 | 89 | 117 | 129 | 115 | 115 | 115 | 107 | 95 | 96 | |||||

| 80–84 | 104 | 192 | 210 | 228 | 211 | 222 | 216 | 203 | 175 | 179 | ≥ 80 | 434 | 431 | 336 | 267 |

| 85–89 | 164 | 268 | 372 | 368 | 338 | 383 | 339 | 329 | 308 | 292 | |||||

| 90–94 | 479 | 428 | 403 | 440 | |||||||||||

| ≥90 | 231 | 339 | 457 | 489 | 531 | 503 | |||||||||

| ≥95 | 498 | 446 | 438 | 448 | |||||||||||

| Men | |||||||||||||||

| 50–54 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| 55–59 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | |||||

| 60–64 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 11 | 14 | 9 | 8 | 8 | |||||

| 65–69 | 9 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 22 | 17 | 23 | 16 | 14 | 16 | 65–79 | 48 | 51 | 36 | 30 |

| 70–74 | 21 | 24 | 32 | 38 | 37 | 33 | 29 | 31 | 29 | 27 | |||||

| 75–79 | 29 | 55 | 65 | 68 | 66 | 64 | 67 | 59 | 54 | 57 | |||||

| 80–84 | 31 | 84 | 129 | 149 | 107 | 117 | 118 | 115 | 110 | 115 | ≥ 80 | 226 | 251 | 224 | 168 |

| 85–89 | 87 | 163 | 212 | 238 | 175 | 225 | 253 | 200 | 194 | 210 | |||||

| 90–94 | 292 | 310 | 308 | 284 | |||||||||||

| ≥90 | 92 | 324 | 370 | 388 | 337 | 370 | |||||||||

| ≥95 | 593 | 393 | 461 | 435 | |||||||||||

aData presented separately for cervical and trochanteric in the original manuscript.

Figure 1.

Projected annual Swedish population for the period 2010–2050, in total and divided into age classes.

Results

In the period 2002–2012, there were 7,385 hip fractures in individuals aged ≥ 50 years in Malmö (during 1,406,356 person years). Age-stratified sex-specific hip fracture rates are given in Table 1 and nationwide projections are presented in Figure 2B. When using the average annual Malmö rates in 5-year age strata, approximately 30,000 hip fractures would be expected to occur in Sweden in 2050 (Figure 2B).

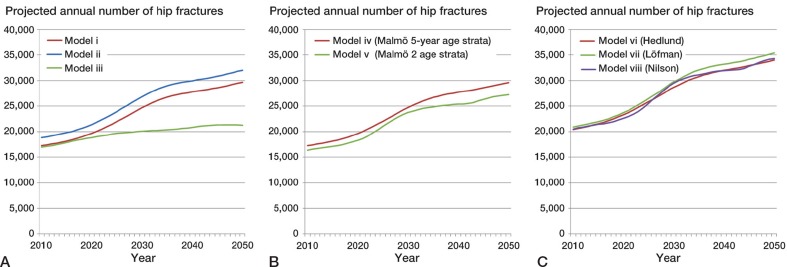

Figure 2.

Projected numbers of hip fractures in Sweden for the period 2010–2050 based on: A. Nationwide Swedish hip fracture rates for the year 2002 in one-year age strata (≥ 50 years) (model i), average rates for the period 1987–2002 in one-year age strata (≥ 50 years) (model ii), and the rate for 2002 in only one stratum (≥ 50 years) (model iii). B. Local average rates for Malmö, Sweden, for the period 2002–2012 in 5-year age strata (≥ 50 years) (model iv) and in 2 age strata (65–79 years and ≥ 80 years) (model v). C. Previously published Swedish hip fracture rates for the period 1972–1981 presented in 5-year age strata (≥ 50 years) (model vi) (Hedlund et al. 1987), for the period 1982–1996 presented in 5-year age strata (≥ 50 years) (model vii) (Lofman et al. 2002), and for 2009 presented in 2 age strata (65–79 years and ≥ 80 years) (Nilson et al. 2013).

We also made projections based on our previously published nationwide rates. According to the first model (model (i), based on the sex-specific nationwide incidence rates from the year 2002, in 1-year age classes), the annual number of hip fractures in Sweden will increase by 350 fractures on average per year from 2002 to 2050 (204 for women and 147 for men), resulting in about 30,000 hip fractures in 2050, corresponding to an increase by a factor of 1.9 (1.7 in women and 2.3 in men) (Figure 2A). According to the second model (model (ii), based on the sex-specific nationwide incidence rates for the period 1987–2002 in 1-year age classes), the annual number of hip fractures will increase by a factor of 2.0 in the period 2002–2050 (Figure 2A). According to the projection model based on nationwide low-resolution data (iii), without taking demographic shifts within the age strata ≥ 50 years into account, the number of hip fractures will increase only by a factor 1.3 in the same period (Figure 2A).

Discussion

The devastating epidemic of hip fractures has been described for a long time, but it has recently been defused by reports of a decrease in age-adjusted rates. Our findings dampen the the optimism associated with this decrease. In the year 2050, the annual number of hip fractures in Sweden will have approximately doubled compared to 2002. This is a result of changes in age-specific fracture incidence during the last decade, an increase in the population at risk, and changes in age distribution within this population—with a higher proportion of elderly men and women in 2050 than in 2002.

To put our projection (based on data from the period 1987–2002) (Rosengren et al. 2012) into perspective, we identified other studies on epidemiology of hip fracture in adults in Sweden with data on men and women over 50 years of age presented in 5-year age classes (Table). For the purpose of illumination, we made projections based on the rates of Hedlund et al. (1987) (for the period 1972–81) and Lofman et al. (2002) (for the period 1982–1996). The resulting numbers for the year 2050 (Figure 2C) were 10–15% higher than the projections based on our nationwide rates (1987–2002) (Rosengren et al. 2012) and our recent local rates (2002–2012), reflecting the effect of a down-turn in incidence. Löfman et al. (2002) made projections of their own using 2 prediction models for the number of hip fractures in Östergötland County, Sweden. For the period 2002–2010, they found a decrease of 11% when they assumed a continued decrease in incidence rates (as seen during their examination period of 1982–96), but stable numbers when they based the projection on the average incidence during the examination period 1982–1996, due to an anticipated transient decrease in the population at risk.

The third model (model (iii), using low-resolution data) differs substantially from the other 2, and with its deliberate underestimation, it illustrates the necessity of using high-resolution data for projections (Figure 2A).

A recent nationwide Swedish study on trends in hip fracture rates from 1987 to 2009 by Nilson et al. (2013) presented absolute annual sex-specific hip fracture rates only for the 3 years 1987, 1997, and 2009 available for projections. The authors, however, only included individuals aged ≥ 65 years stratified in 2 wide age classes (65–79 years and ≥ 80 years) and they used a different definition of hip fracture from that used in other studies (Table). Nilsson et al. included all inpatient care for hip fracture, while other studies have also used the criterion of relevant surgery or acute fracture for inclusion, thereby actually reflecting acute hip fractures. The method used by Nilson et al. (2013) would therefore lead to an overestimation of fractures due to re-admissions, re-operations, and transfers between units being included in the numerator for the incidence estimations. However, for the sake of completeness, a projection based on the 2009 rates presented by Nilson et al. (2013) is presented in Figure 2C.

The fact that the projection based on Malmö data from 2002–2012 resulted in the lowest numbers could be due to several factors, the most obvious being a further decrease in rates compared to earlier rates of Hedlund et al. (1987) and Löfman et al. (2002). It could be argued that the rates for Malmö cannot be generalized to the Swedish population, as increasing hip fracture risk with increasing latitude has been described (Johnell et al. 2007).

The strengths of the study include the recent data from local records and the long registration period for nationwide data. A recent report (Rosengren et al. 2012) indicated that hip fracture rates are influenced by period and cohort effects, but based on the long registration period, the results of the second model (ii) (based on overall rates from the period 1987–2002) must be considered to be robust and they do not differ much from the results of model (i) (based on rates from 2002 only) or from projections from older Swedish studies (Figure 2C and Table 1) (Hedlund et al. 1987, Lofman et al. 2002). The end of actual nationwide data in 2002 is a drawback that has been partially overcome by the recent data from Malmö. While the annual number of hip fractures is difficult to appraise from registries, relative changes are more easily estimated in most contexts, as current numbers are available in local registries or osteosynthesis invoice archives.

In summary, the annual number of hip fractures in Sweden will almost double between 2002 and 2050, resulting in roughly 30,000 fractures in that year. Already now, it is apparent that we must optimize measures to prevent hip fracture and prepare for major demands on resources in the future. Time trends in hip fracture rates and changes in population size and age distribution must be monitored on a continuous basis. Changes in any of these will affect the relevant endpoint, i.e. the number of hip fractures in future.

Acknowledgments

BR and MK planned the study. BR did all the calculations and wrote the first draft. BR and MK together revised the manuscript to its final form.

The authors state that there are no competing interests. Funding was received from ALF-Skåne, FoU Skåne, the Herman Järnhardt Foundation, and the Johan and Greta Kock Foundation.

References

- Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ., 3rd Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection . Osteoporos Int. 1992;2:6, 285–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01623184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanwal DK, Dennison EM, Harvey NC, Cooper C. Epidemiology of hip fracture: Worldwide geographic variation . Indian J Orthop. 2011;45:1, 15–22. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.73656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg B, Duppe H, Nilsson B, Redlund-Johnell I, Sernbo I, Obrant K, et al. Incidence of hip fractures in Malmo, Sweden (1950-1991) . Bone. 1993;14(Suppl 1):S23–9. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(93)90345-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture . Osteoporos Int. 1997;7:5, 407–13. doi: 10.1007/pl00004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund R, Lindgren U, Ahlbom A. Age- and sex-specific incidence of femoral neck and trochanteric fractures. An analysis based on 20,538 fractures in Stockholm County, Sweden, 1972-1981 . Clin Orthop. 1987;222:132–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnell O, Borgstrom F, Jonsson B, Kanis J. Latitude, socioeconomic prosperity, mobile phones and hip fracture risk . Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:3, 333–7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Palvanen M, Vuori I, Jarvinen M. Hip fractures in Finland between 1970 and 1997 predictions for the future . Lancet. 1999;353(9155):802–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Palvanen M, Vuori I, Jarvinen M. Nationwide decline in incidence of hip fracture . J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:12, 1836–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofman O, Berglund K, Larsson L, Toss G. Changes in hip fracture epidemiology: redistribution between ages, genders and fracture types . Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:1, 18–25. doi: 10.1007/s198-002-8333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilson F, Moniruzzaman S, Gustavsson J, Andersson R. Trends in hip fracture incidence rates among the elderly in Sweden 1987-2009 . J Public Health (Oxf) 2013;35(1):125–31. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fds053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogmark C, Sernbo I, Johnell O, Nilsson JA. Incidence of hip fractures in Malmo, Sweden, 1992-1995. A trend-break . Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70(1):19–22. doi: 10.3109/17453679909000950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren BE, Ahlborg HG, Mellstrom D, Nilsson JA, Bjork J, Karlsson MK. Secular trends in Swedish hip fractures 1987-2002: birth cohort and period effects . Epidemiology. 2012;23(4):623–30. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318256982a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden Utrikes födda 2012. http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Artiklar/Fortsatt-okning-av-utrikes-fodda-i-Sverige/ Statistics Sweden. 2013 [cited 2014 Feb 5]. Available from:

- Stadskontoret Malmö Malmö 2012 Befolkningsbokslut. http://www.malmo.se/download/18.24a63bbe13e8ea7a3c692fc/1383644210075/Rapport+Bef+Bokslut+2012.pdf 2013 [cited 2014 Feb 5]. Available from: