Abstract

Background and purpose

The Lubinus SP II stem is well documented in both orthopedic registries and clinical studies. Worldwide, the most commonly used stem lengths are 150 mm and 170 mm. In 1995, the 130-mm stem was introduced, but no outcome data have been published. We assessed the long-term survival of the Lubinus SP II 130-mm stem in primary total hip arthroplasty.

Patients and methods

In a retrospective cohort study, we evaluated 829 patients with a Lubinus SP II primary total hip arthroplasty (932 hips). The hips were implanted between 1996 and 2001. The primary endpoint was revision for any reason. The mean follow-up period was 10 (5–15) years.

Results

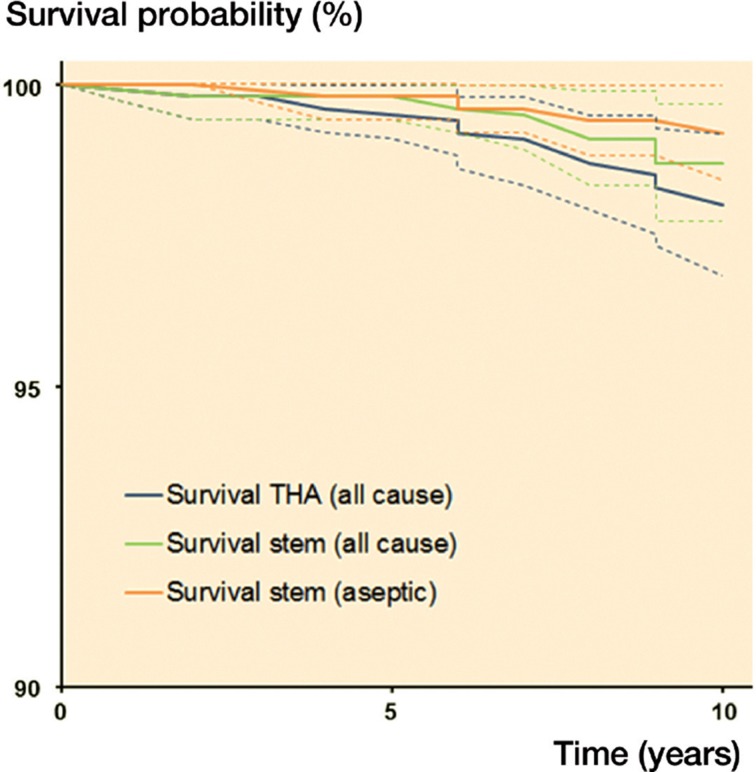

Survival analysis showed an all-cause 10-year survival rate of the stem of 98.7% (95% CI: 99.7–97.7), and all-cause 10-year survival of the total hip arthroplasty was 98.3% (95% CI: 99.3–97.3).

Interpretation

Excellent long-term results can be achieved with the cemented Lubinus SP II with the relatively short 130-mm stem. This stem has potential advantages over its 150-mm and 170-mm siblings such as bone preservation distal to the stem, better proximal filling around the prosthesis, and easier removal.

The Lubinus SP II stem is a well-documented prosthesis (Annaratone et al. 2000, Lubinus et al. 2002, Catani et al. 2005, Wierer et al. 2013). The anatomical-shaped SP stem was introduced in 1982 as a monoblock prosthesis, and since 1984 it has been available as the modular SP II system. The anatomical-shaped stem provides a uniform cement mantle surrounding the prosthesis, which reduces the risk of contact between the prosthesis and cortical bone. It has been hypothesized that this more uniform cement mantle improves the survival of the prosthesis (Lubinus et al. 2002). Worldwide, the most commonly used stem lengths are 150 and 170 mm. In 1995, the 130-mm stem was introduced and since its introduction this has been the most frequently used stem in our hospital. This shorter stem has several theoretical advantages, such as preservation of bone stock and possibly a better filling of the proximal femur, subsequently leading to better options for revision. Theoretically, however, the shorter stem has less rotational stability.

There is no literature specifically about the SP II 130-mm stem. Reports on 150-mm and 170-mm SP II stems show survival rates ranging from 90% to 98%, with a minimum of 10 years of follow-up (Annaratone et al. 2000, Lubinus et al. 2002, Catani et al. 2005, Makela et al. 2008, Espehaug et al. 2009, Wierer et al. 2013). The Swedish registry data are almost uniformly (> 98%) based on the 150-mm stem (Swedish register database 2013). We hypothesized that the long-term survival of the Lubinus SP II 130-mm stem in primary total hip arthroplasty would be no different from the reported survival of the 150-mm and 170-mm SP II femoral stems. This hypothesis was tested in a retrospective cohort study using revision for any reason as the primary endpoint.

Patients and methods

Source of data

Data were extracted from the medical registration system, calling the patients and consulting the patients’ (former) general practitioners (GPs). If patients had died, their relatives or GPs were asked if any revision of the total hip arthroplasty had occurred.

Study population

Between July 1996 and December 2001, a total of 1,248 total hip arthroplasties were performed at our hospital. In 932 primary hip arthroplasties (in 829 patients), the Lubinus SP II was used (Waldemar Link, Hamburg, Germany). We included all patients with a primary total arthroplasty of the hip with the Lubinus SP II 130 mm. Selection criteria for a cemented SP II prosthesis were mainly based on older age (> 60 years) and radiographic bone quality. However, the anatomical length of the femur was not considered. In this period, younger patients with sufficient bone quality mainly received uncemented femoral prostheses. Their results have been published (Goosen et al. 2005). Also in this period, we used the 170-mm SP II in selected cases (< 20 patients) with insufficient proximal bone stock due to secondary osteoarthritis (e.g. posttraumatic). Until 2000, the 130-mm Lubinus SP II stem was combined with a Co-Cr-Mo 28-mm head and a Lubinus IP cup (Waldemar Link). In 2000, the IP cup was replaced with the Flanged Anti Luxation (FAL) cup (Waldemar Link) with 28-mm Biolox-forte ceramic head (CeramTec, Plochingen, Germany). All components were cemented using Simplex bone cement (Stryker).

The Lubinus SP II is an anatomical, S-shaped modular stem (of Co-Cr-Mo) with an anatomical anteversion and a 12- to 14-mm taper (Figure 1). The stem is available in 7 sizes (left and right) and 3 different caput collum diaphysis (CCD) angles (117°, 126°, and 135°). The applied IP and FAL acetabular components are cemented polyethylene cups in eight different sizes ranging from 44 mm to 58 mm with an inner diameter of 28 mm.

Figure 1.

The anatomical S-shaped Lubinus SP II stem.

829 patients (932 hips) were included in the study. 103 patients were operated bilaterally (Table 1). The mean follow-up period was 10 (5–15) years. During the follow-up period, 400 patients died and 21 (2%) were lost to follow-up. Furthermore, 29 patients had a follow-up of less than 5 years and were excluded from the risk factor analysis (but were included in the Kaplan-Meier curve).

Table 1.

Demographics

| Age | |

| Mean, years (SD) | 72 (8.0) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 223 (24%) |

| Women | 709 (76%) |

| Side of surgery | |

| Right | 467 (50%) |

| Left | 465 (50%) |

| Preoperative diagnosis | |

| Primary osteoarthritis | 863 (93%) |

| Secondary osteoarthritis | 52 (5.6%) |

| Inflammatory diseases | 35 (3.8%) |

| Avascular necrosis | 6 (0.6%) |

| Childhood diseases | 1 (0.1%) |

| Other | 10 (1.1%) |

| Fracture | 17 (1.8%) |

| Stem size | |

| 01 | 15 (1.6%) |

| 1 | 268 (29%) |

| 2 | 277 (30%) |

| 3 | 247 (27%) |

| 4 | 123 (13%) |

| 5 | 1 (0.1%) |

In all but 2 hips (one 117° and one 135°), the 126° CCD angle was used.

All patients had surgery in the lateral decubitus position with a posterolateral or anterolateral approach, depending on the preference of the surgeon. In the study period, line-to-line cementing to the last broach was used and the prosthesis was rarely undersized. 5 different surgeons performed the surgery. Perioperatively, systemic antibiotic prophylaxis was given (cefazoline). Patients received low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) until adequate INR, and a vitamin K antagonist, which was continued until 3 months after surgery. Patients were allowed and encouraged to start full weight bearing on the first postoperative day.

Statistics

The follow-up period started on the day of implantation of the THA. It ended on the day of revision, death, or last available follow-up measurement until April 30, 2012. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed for the total hip arthroplasty, the cup, and the stem. We also performed analysis of the first implanted hip as for all hips. Some studies have found that bilaterally implanted THAs show better survival than unilaterally implanted hips (Visuri et al. 2002). However, other studies have found that this possible bias is negligible (Robertson and Ranstam 2003, Lie et al. 2004).

Standard-case, worst-case, and best-case scenarios were analyzed.

Cox regression analysis was then conducted to identify independent risk factors that would best explain revision of the stem in our population over 5 or more years of follow-up. In Cox regression, only the first implanted hip (in patients with a bilateral THA) was used, to avoid dependency of data from bilateral arthroplasties. The potential risk factors selected for this analysis were age, sex, and diagnosis (based on dummy variables using arthrosis as reference). Only significant factors in the bilateral analysis were subsequently fitted into a multivariable analysis based on a stepwise-backward selection procedure. However, as the bilateral analysis did not generate any significant factors and the analysis did not comply with the assumptions, this multivariable stage of the analysis was not reached and—as a consequence—no independent risk factors for stem revision could be identified. Assumptions were assessed by evaluating log-log plots. 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

A 2-sided p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 20.0.

Results

Survival

The best-case scenario was a 10-year survival of 98.7% (CI: 99.7–97.7) for the stem. In the worst-case scenario, we found a 10-year survival of 96.1% (CI: 94.9–97.3) for the stem (Figure 2 and Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Survival curves for the THA and stem: all-cause survival of the THA (blue line), all-cause survival of the stem (green line), and aseptic survival of the stem (orange line). Dotted lines show confidence intervals for the respective survival curves.

Table 2.

Survival rates at 10 years for THA, stem, and cup a (with all hips included)

| THA (95% CI) | Stem (95% CI) | Cup (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revision for any reason | 98.3 (99.3–97.3) | 98.7 (99.7–97.7) | 98.7 (99.7–97.7) |

| Aseptic loosening | 99.2 (99.9–98.4) | 99.4 (99.9–98.4) | 99.7 (100–99.3) |

a After 10 years, 406 patients were at risk.

Table 3.

Survival rates at 10 years for THA, stem, and cup a a (with only the first implanted hip included)

| THA (95% CI) | Stem (95% CI) | Cup (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revision for any reason | 98.6 (99.6–97.6) | 98.9 (99.9–97.9) | 99.0 (99.8–98.2) |

| Aseptic loosening | 99.4 (100–98.6) | 99.3 (99.9–98.7) | 99.8 (100–99.4) |

a After 10 years, 357 patients were at risk.

In the multivariable Cox regression analysis, we failed to identify a single risk factor (from sex, side, femoral stem size, and preoperative diagnosis) for stem revision.

Discussion

We found excellent 10-year survival rates (∼99%) for the relatively short 130-mm Lubinus SP II stem, for aseptic loosening and for all-cause revision. The relatively unknown 130-mm SP II stem has several potential advantages over the larger 150-mm and 170-mm stems. First, the shorter stem preserves bone distal to the prosthesis. Secondly, the proximal filling might be better with the use of this shorter stem, leading to a more even distribution of cement—especially in Dorr type A (champagne-fluted) femora. Thirdly, in our experience this stem is more easily removed from its cement mantle than its longer peers, giving the opportunity of cement-in-cement revision. Theoretically, the shorter stem design could result in less rotational stability compared to the 150-mm and 170-mm siblings. This disadvantage does not appear to influence survival, possibly because of better proximal filling, which has promoted rotational stability in experimental studies (Janssen et al. 2009).

We believe that our results are valid because we had a negligible loss-to-follow-up rate (2%). Even in the worst-case scenario, the survival rate was 96.1% at 10-year follow-up.

The study had some potential weaknesses. First, we did not evaluate the clinical and radiographic condition of the patients. The clinical results could therefore have been worse than the survival data suggest, a weakness that also occurs in registry-based studies. Our patients were relatively old (mean age: 72.3 years) and our results may not apply to the younger age group. In several studies, young age has been considered to be a risk factor for revision (Prokopetz et al. 2012).

There is an ongoing discussion about whether to use cemented or uncemented designs (Hailer et al. 2010, Corten et al. 2011). A recently published randomized controlled trial performed by Corten et al. (2011) showed clearly favorable results regarding the cementless stem in the younger population. Hailer et al. (2010) reviewed information from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (SHAR) to compare cemented and cementless femoral stems. They found superior survival in the cemented stems. Stratification into age groups showed inferior survival rates for the cementless stem, except for the age group > 75 years (Hailer et al. 2010). Our study supports the use of the cemented shorter 130-mm stem in older patients especially.

Compared to commonly used straight stem designs, the anatomical-shaped Lubinus SP II has better centralization of the stem, which leads to more even thickness of the cement mantle (Breusch et al. 2001). One study showed that the Lubinus SP II had the lowest number of cement cracks compared to 3 other cemented stem designs (Stolk et al. 2007). Other studies have shown less than 1% cracks in the cement mantle (compared to 6% and 8% for the Charnley and Exeter stems, respectively) (Perez and Palacios 2010, Waanders et al. 2011). The relevance of these mechanical advantages is debatable, since all stem designs in these studies have excellent survival.

We found no effect of stem size, even though the survival of the smallest 01 SP II stem is reportedly inferior to that of the larger stems (Thien and Karrholm 2010). Only 1% of patients in our population were fitted with the smallest stem size. This is most likely due to better proximal filling and line-to-line cementing, allowing a larger stem size to be inserted when using the shorter 130-mm SP II.

We did not adjust the length of the SP II to the length of the femur, and instead used the 130-mm SP II stem in all patients with normal proximal bone stock. We could not find any literature regarding tailoring of the stem length to the anatomical length of the femur. The equally favourable results obtained in men and women also suggest that this is not an important factor with the cemented SP II stem. Furthermore, there is some evidence that shorter (uncemented) stems provide more anatomical strain in the proximal femur (Arno et al. 2012).

In summary, we found excellent survival results (98.6% all-cause and 99% for aseptic loosening) of the relatively short cemented Lubinus SP II 130-mm stem. Because of the excellent survival rate, preservation of bone stock, and the advantages in revision hip arthroplasty, we recommend using the 130-mm SP II stem over use of its longer siblings.

Acknowledgments

WP: data collection and writing of the article. RM: data collection and supervision of the writing. BJK: statistical analysis, supervision, and correction of the article. CCPMV and HBE: conception of the study, supervision, and correction of the article.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Annaratone G, Surace FM, Salerno P, Regis GF. Survival analysis of the cemented SP II stem. J Orthopaed Traumatol. 2000;1:41–5. [Google Scholar]

- Arno S, Fetto J, Nguyen NQ, Kinariwala N, Takemoto R, Oh C, Walker PS. Evaluation of femoral strains with cementless proximal-fill femoral implants of varied stem length . Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2012;27:7, 680–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breusch SJ, Lukoschek M, Kreutzer J, Brocai D, Gruen TA. Dependency of cement mantle thickness on femoral stem design and centralizer . J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:5, 648–57. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.23920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani F, Ensini A, Leardini A, Bragonzoni L, Toksvig-Larsen S, Giannini S. Migration of cemented stem and restrictor after total hip arthroplasty: A radiostereometry study of 25 patients with lubinus SP II stem . J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:2, 244–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corten K, Bourne RB, Charron KD, Au K, Rorabeck CH. What works best, a cemented or cementless primary total hip arthroplasty?: Minimum 17-year followup of a randomized controlled trial . Clin Orthop. 2011;469(1):209–17. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1459-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. 18 years of results with cemented primary hip prostheses in the norwegian arthroplasty register: Concerns about some newer implants . Acta Orthop. 2009;80:4, 402–12. doi: 10.3109/17453670903161124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosen JH, Swieringa AJ, Keet JG, Verheyen CC. Excellent results from proximally HA-coated femoral stems with a minimum of 6 years follow-up: A prospective evaluation of 100 patients . Acta Orthop. 2005;76:2, 190–7. doi: 10.1080/00016470510030562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailer NP, Garellick G, Karrholm J. Uncemented and cemented primary total hip arthroplasty in the swedish hip arthroplasty register . Acta Orthop. 2010;81:1, 34–41. doi: 10.3109/17453671003685400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen D, van Aken J, Scheerlinck T, Verdonschot N. Finite element analysis of the effect of cementing concepts on implant stability and cement fatigue failure . Acta Orthop. 2009;80:3, 319–24. doi: 10.3109/17453670902947465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie SA, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI, Gjessing HK, Vollset SE. Dependency issues in survival analyses of 55,782 primary hip replacements from 47,355 patients . Stat Med. 2004;23:20, 3227–40. doi: 10.1002/sim.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubinus P, Klauser W, Schwantes B, Eberle R. Cemented total hip arthroplasty: The SP-II femoral component. GIOT. 2002;28:221–6. [Google Scholar]

- Makela K, Eskelinen A, Pulkkinen P, Paavolainen P, Remes V. Cemented total hip replacement for primary osteoarthritis in patients aged 55 years or older: Results of the 12 most common cemented implants followed for 25 years in the finnish arthroplasty register . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008;90(12):1562–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B12.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez MA, Palacios J. Comparative finite element analysis of the debonding process in different concepts of cemented hip implants . Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:6, 2093–106. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9996-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokopetz JJ, Losina E, Bliss RL, Wright J, Baron JA, Katz JN. Risk factors for revision of primary total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:251. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J. No bias of ignored bilaterality when analysing the revision risk of knee prostheses: Analysis of a population based sample of 44,590 patients with 55,298 knee prostheses from the national swedish knee arthroplasty register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolk J, Janssen D, Huiskes R, Verdonschot N. Finite element-based preclinical testing of cemented total hip implants . Clin Orthop. 2007;456:138–47. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31802ba491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish register database 2013 personal communication: http://www.shpr.se/en/

- Thien TM, Karrholm J. Design-related risk factors for revision of primary cemented stems. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:4, 407–12. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.501739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waanders D, Janssen D, Mann KA, Verdonschot N. The behavior of the micro-mechanical cement-bone interface affects the cement failure in total hip replacement . J Biomech. 2011;44:2, 228–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierer T, Forst R, Mueller LA, Sesselmann S. Radiostereometric migration analysis of the lubinus SP II hip stem: 59 hips followed for 2 years . Biomed Tech (Berl) 2013;58:4, 333–41. doi: 10.1515/bmt-2012-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visuri T, Turula KB, Pulkkinen P, Nevalainen J. Survivorship of hip prosthesis in primary arthrosis: Influence of bilaterality and interoperative time in 45,000 hip prostheses from the finnish endoprosthesis register . Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:3, 287–90. doi: 10.1080/000164702320155266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]